Six

THE EARLY YEARS OF CAPE COD NATIONAL SEASHORE

Of Cape Cod’s Great Beach, Henry Thoreau wrote, “They commonly celebrate those beaches only which have a hotel on them. But I wished to see that seashore where the ocean is landlord as well as sea-lord and comes ashore without a wharf for landing.” Thoreau’s wish became reality with Cape Cod National Seashore. But when President Kennedy signed the legislation in 1961, there was little time to celebrate. The great work was just beginning.

On April 8, 1962, Robert F. Gibbs became the first superintendent of Cape Cod National Seashore, after having been superintendent of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Despite some initial resistance (Gibbs moved his family to a rented house only to find a sign by the owner forbidding his occupancy), Gibbs said Cape Cod was the “friendliest place” he had ever seen. He is seen here meeting with First Chief Ranger Van der Lippe in front of Nauset Light.

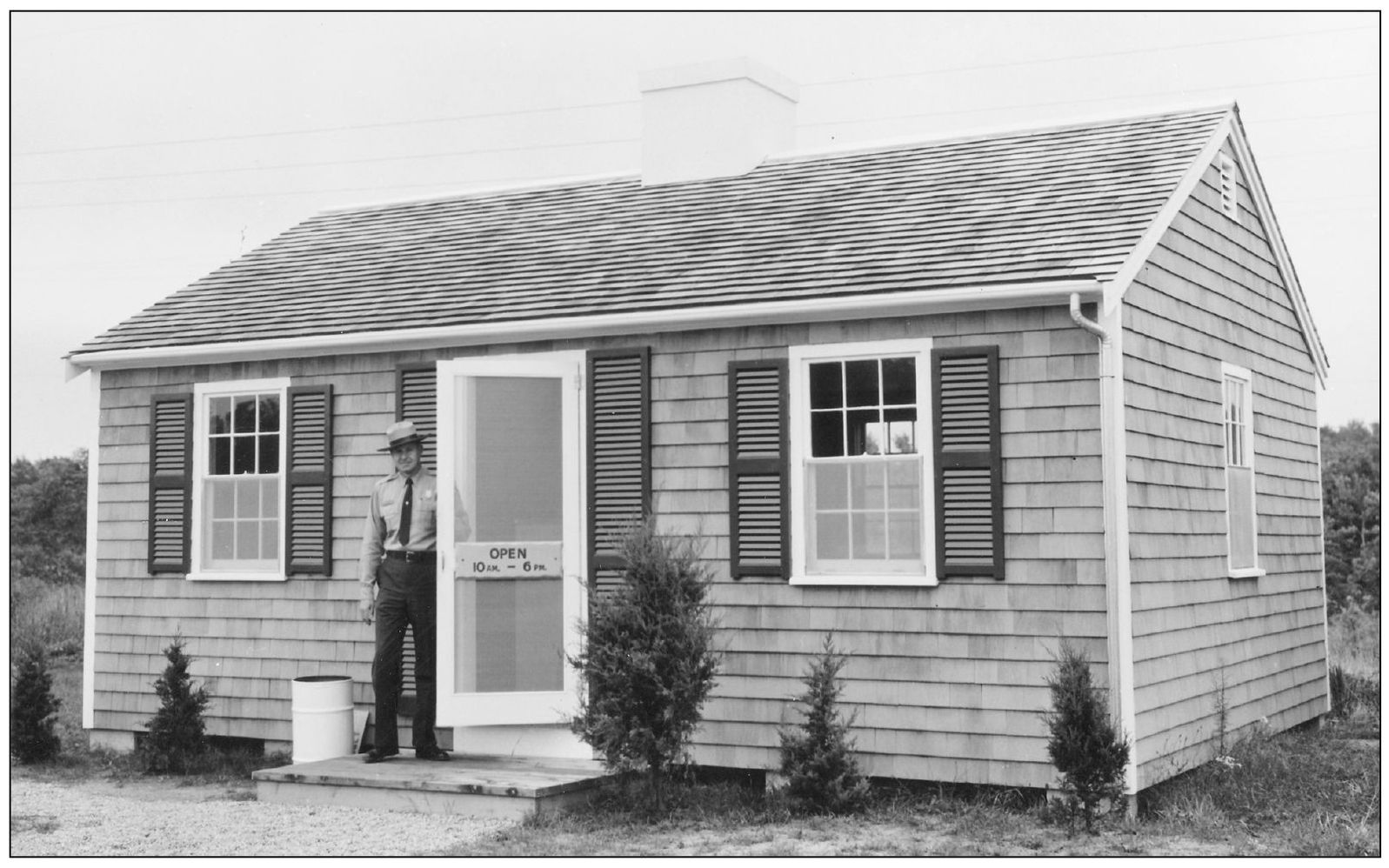

It would be five years from the beginning of the seashore to the great day of its formal dedication in 1966. Meanwhile, there were 3,600 parcels of land to be transferred, construction of visitor centers and offices, and the staffing of the park with rangers, lifeguards, and other workers. This photograph from around 1963 shows the first information booth, just west of Orleans rotary on Highway 6.

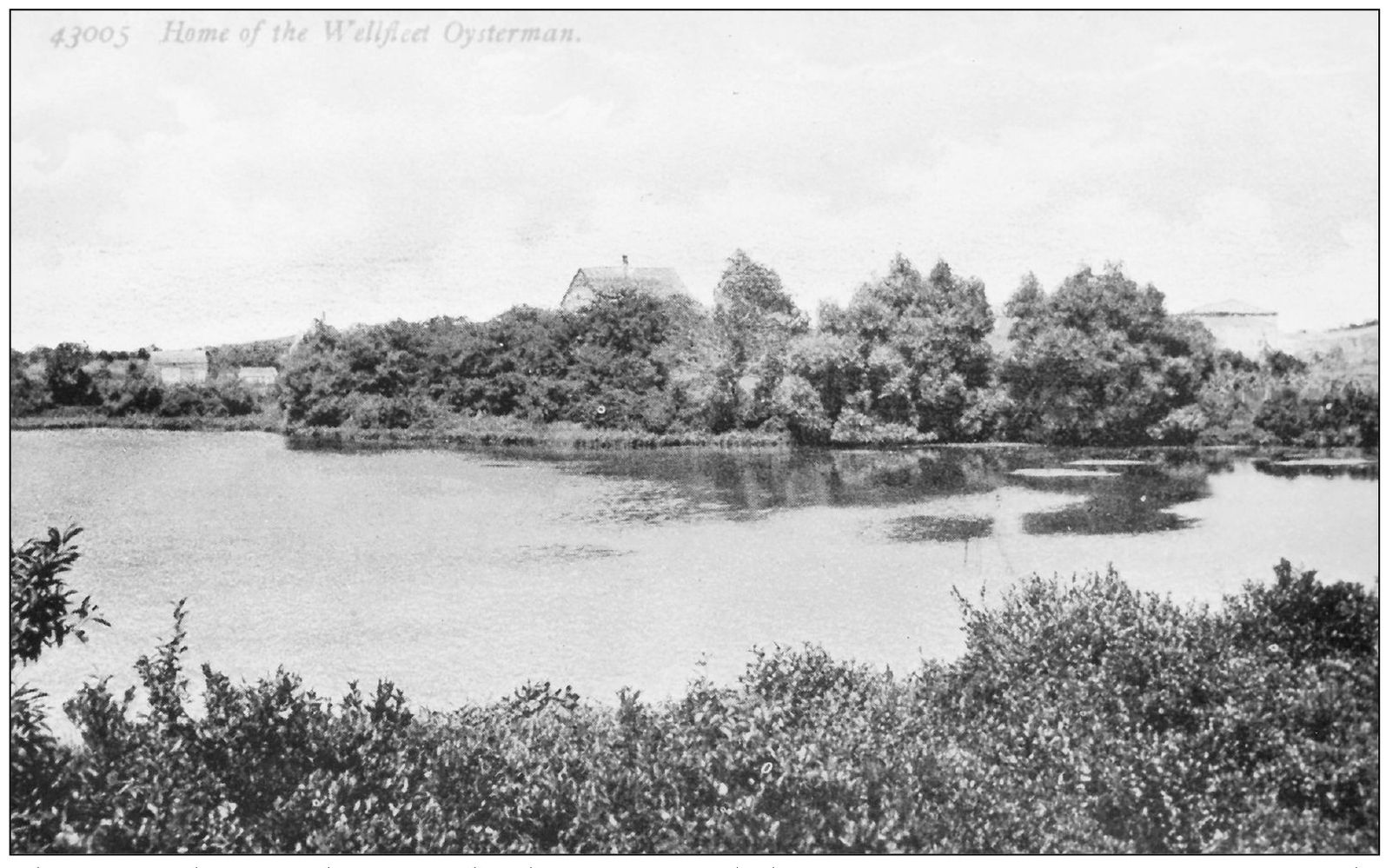

There were about 660 homes and 19 businesses, including gas stations, restaurants, campgrounds, cottage colonies, and golf courses within the new park boundaries. Each came with questions—would homeowners sell to the park? Stay and abide by restrictions? What of motels? Which town-owned parks and beaches would be transferred to the national seashore? The Wellfleet oysterman’s house, above, visited by Thoreau in the 19th century is now within CCNS.

Unique to the park were the agreements available to homeowners within its borders. Homes built before September 1, 1959, could remain. Property with homes built after that date could be taken for public use. Sensitive to landowner apprehension, the national seashore used a spectrum of acquisition techniques, including purchase, occupancy or life tenancy, and of course, gift. The Warren Small farm at Pilgrim Heights, Truro, for example, was given to the seashore by Roger Hagen.

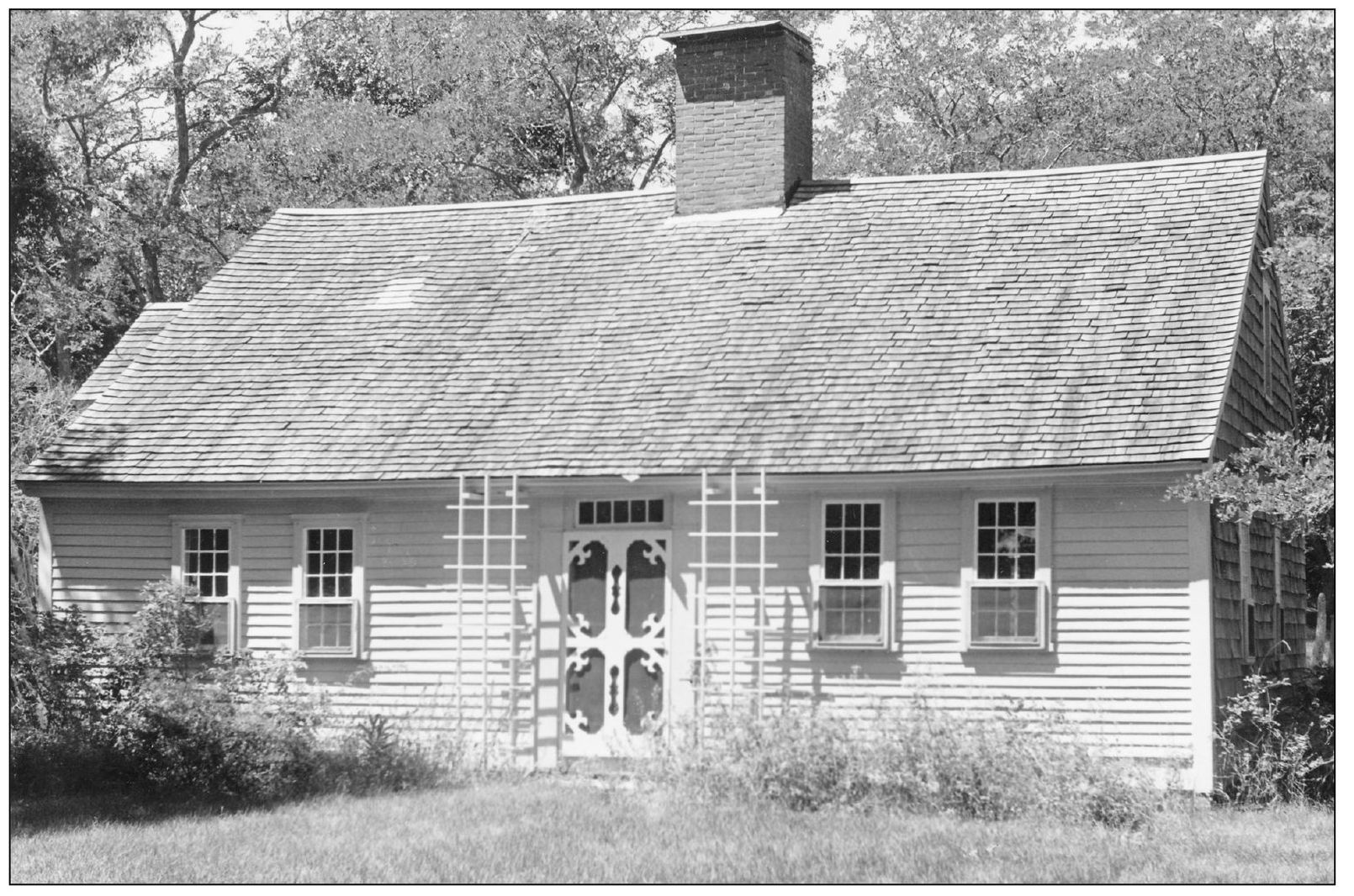

Owners who agreed to sell were given four options: outright sale, sale with the owner retaining life-tenure rights, sale with the owner retaining tenure rights for a fixed period (up to 25 years), or sale of unimproved lands with retention of home site ownership in perpetuity (in which case the national seashore’s right of condemnation was suspended.) George Higgins retained a life tenancy upon transfer of the Atwood-Higgins House in Wellfleet to the Department of the Interior.

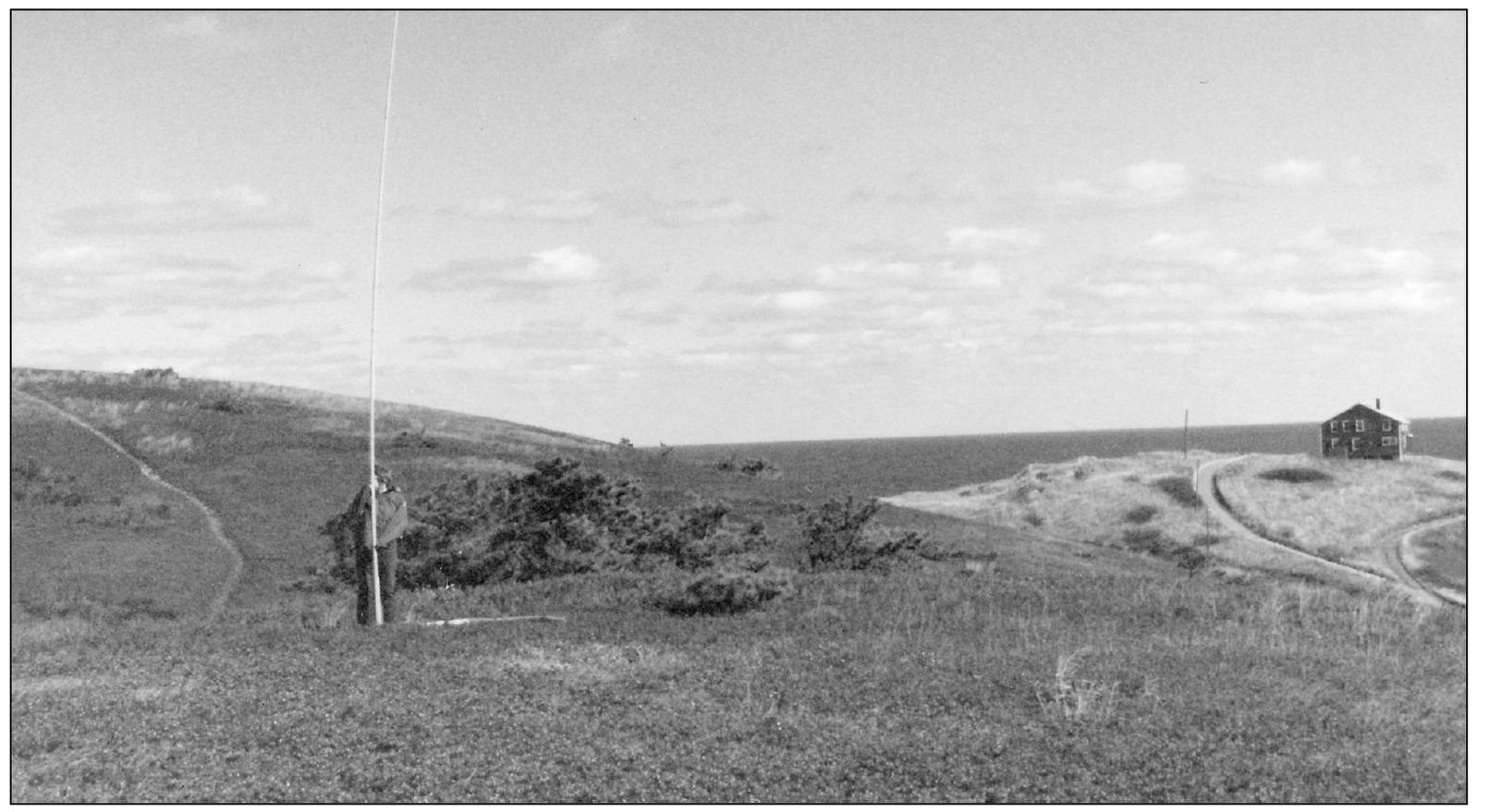

By 1968, the original $16 million allowed for property acquisition was exhausted. With rising costs, even the additional $17.5 million allocated in 1971 was not enough. Those owners who had not sold to the seashore, such as the owner of property like Bearberry Hill in Truro, above, were allowed to stay but were required to abide by national seashore guidelines for development. The National Park Service, however, had little authority to enforce the guidelines.

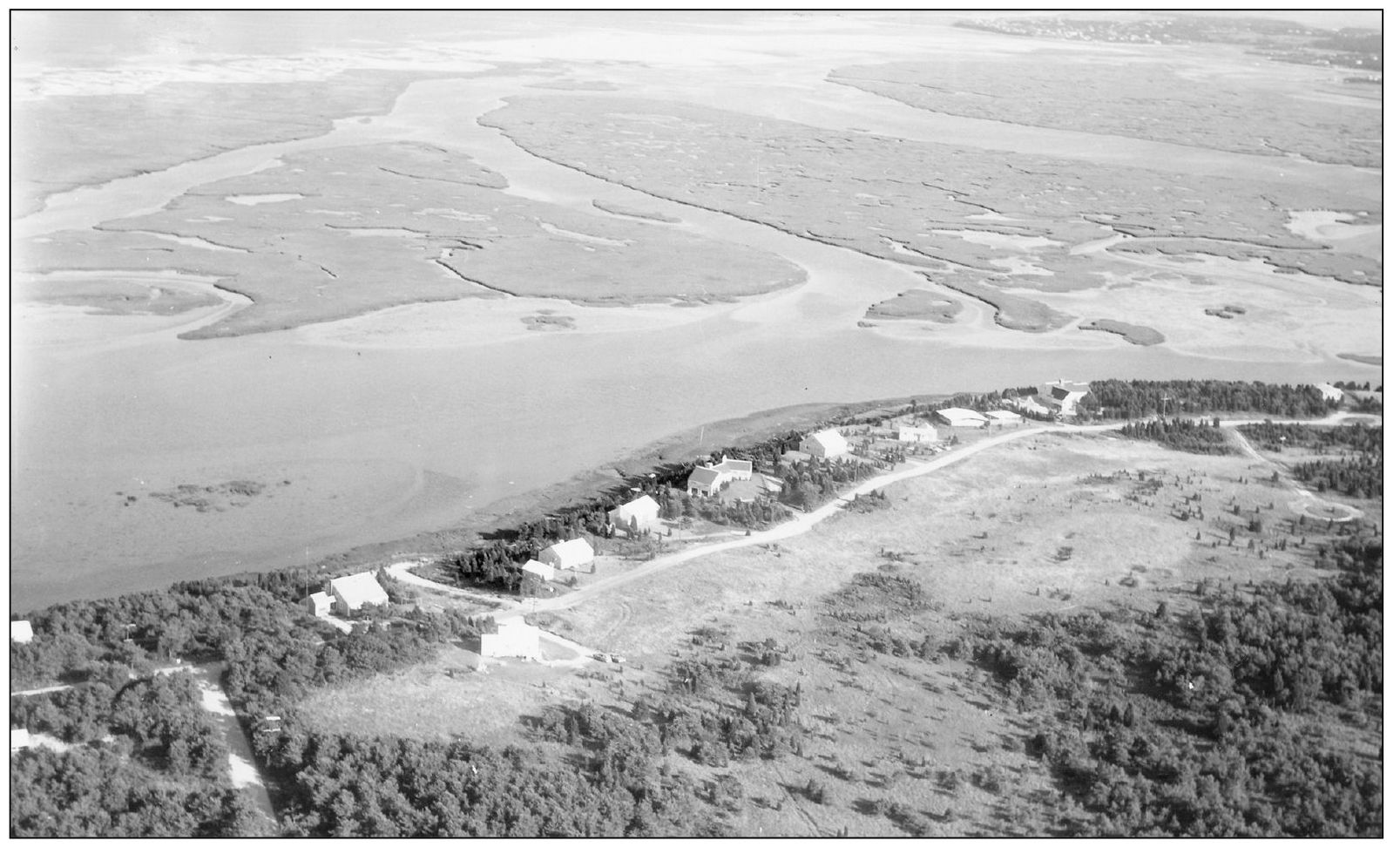

To give legal authority to the national seashore development guidelines, towns were encouraged to adopt the guidelines into their zoning bylaws. Yet the town of Eastham was the only town to have done so. The photograph shows development coexisting with the national seashore in Eastham. The redevelopment possibilities of Seashore properties in other towns were open to interpretation.

The Province Lands in Provincetown and Pilgrim Springs State Park in Truro were conveyed to the United States in 1962. The title to the Province Lands provided that a portion would be subject to a pre-existing lease for the Provincetown Airport. Coast Guard Beach and Nauset Light Beach in Eastham (above) were deeded by the town to the United States in 1963 and 1965, respectively. In return Eastham taxpayers were given free access.

The former site of the Marconi Wireless Station in South Wellfleet became Camp Wellfleet in 1943. It was the antiaircraft artillery training center for Camp Edwards on the Upper Cape. Men were sent from Camp Edwards to train on the firing range of Camp Wellfleet. With the creation of Cape Cod National Seashore, the U.S. Army transferred title in 1961. (Courtesy of William Quinn.)

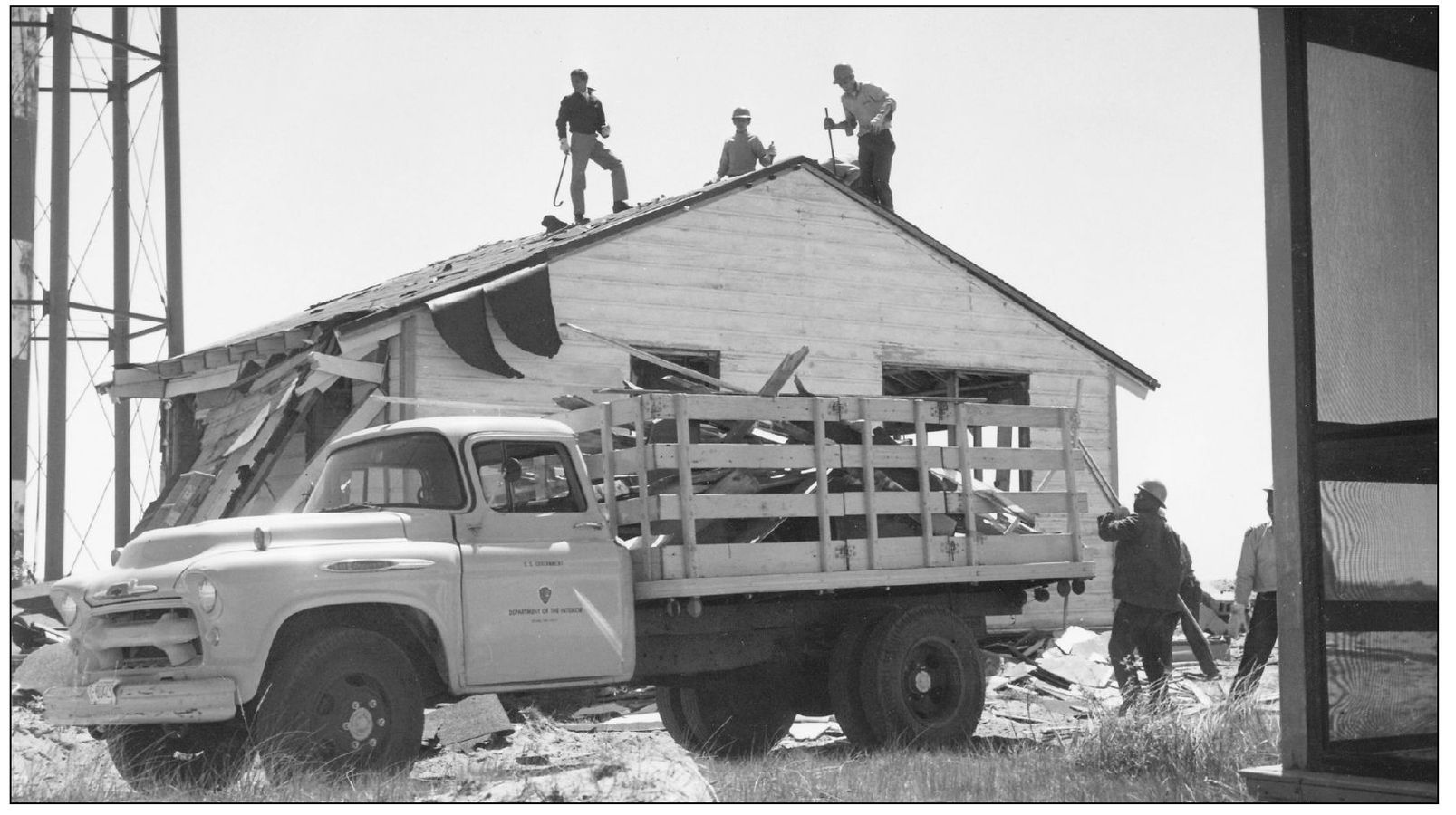

Camp Wellfleet contained 17 single-story barracks that housed 50 men each. There were four company administration and supply buildings, five lavatory buildings, an assembly hall that held 400, an infirmary, a post exchange, ammunition magazine, storehouse, and firefighting unit. The Job Corps arrived in 1964 to remove buildings. (Courtesy of William Quinn.)

The demolition of Camp Wellfleet required the cleanup of many hazards, including thousands of spent shell casings. Certain features would remain as the land was prepared for the construction of the new national seashore headquarters. In fact, a helicopter pad is still visible behind the headquarter buildings.

The first headquarters of Cape Cod National Seashore opened in the Coast Guard Station at Coast Guard Beach, Eastham, in 1961. Currently that building houses Cape Cod National Seashore’s overnight National Environmental Educational Development (NEED) program for school groups. The park’s present administrative headquarters (above) was built near the Marconi Station site in 1965, on land that had been part of Camp Wellfleet.

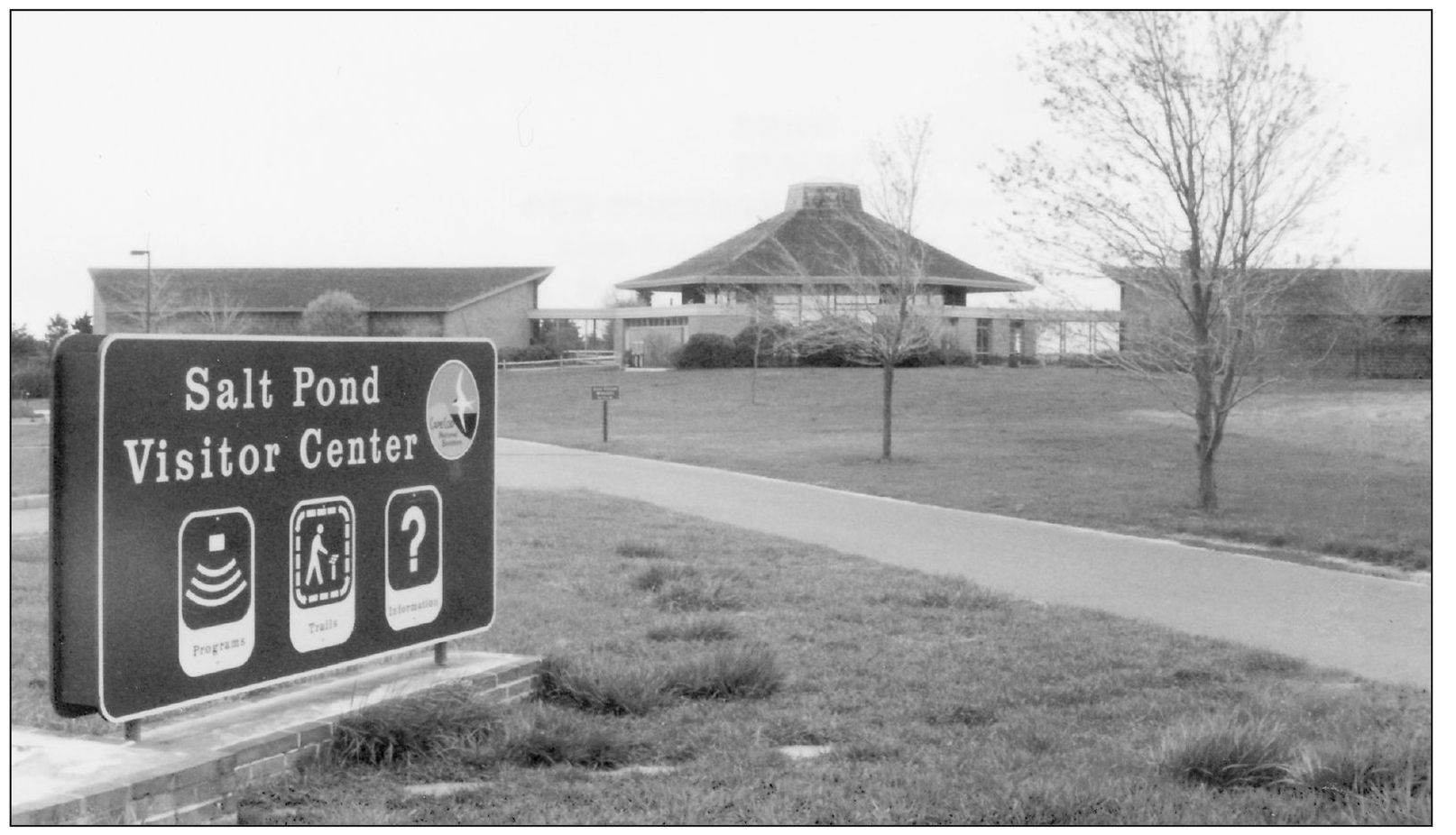

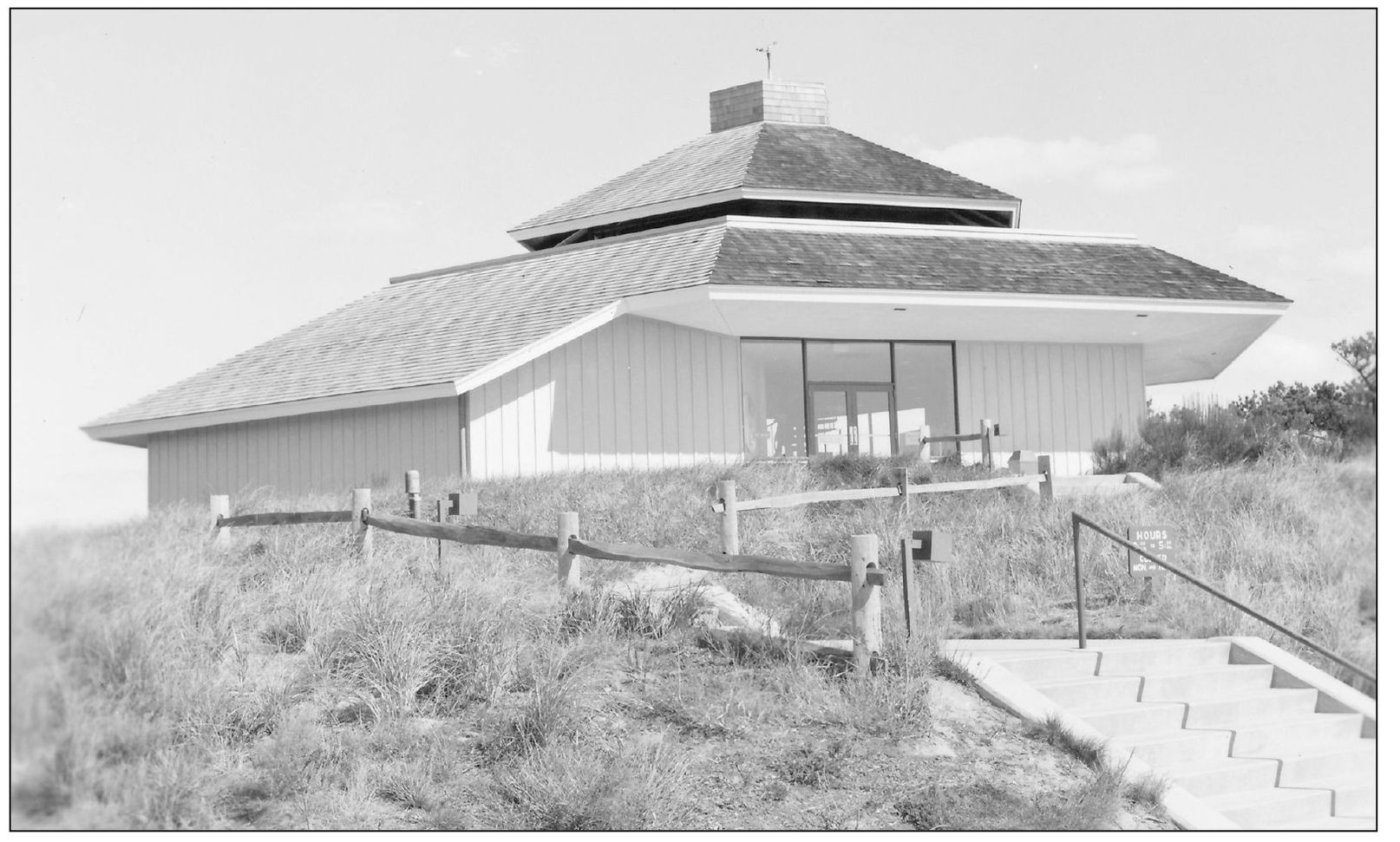

To create a uniform architectural look for National Park Service buildings, the advisory commission sent letters to 12 leading American architects, among them Walter Gropius. The commission was encouraged to combine the best of contemporary and traditional styles. In 1965, the Salt Pond Visitor Center was opened, with panoramic views of Salt Pond and separate museum and auditorium wings. It was controversial at the time, with some people referring to it as “that beehive thing.”

Stanley C. Joseph followed Robert Gibbs as superintendent on January 30, 1966. By then the success of the national seashore was evident—there was traffic congestion, a shortage of parking, and heavy use of the limited bike trails. Land acquisition funds were nearly gone. That year, a second visitor center in the Province Lands was proposed, reviving the previous debate over architectural style. Termed the “Chinese pagoda,” it was dedicated on May 25, 1969.

Kurt Vonnegut Jr., a 15-year resident of the Cape, wrote, “After some of the most amusing wrangling in the history of the National Park Service, Cape Cod National Seashore Park is a reality . . . one of the smallest national parks, and one of the most queerly shaped.” He quoted opponent Chester Crocker of Marston Mills: “Most all of the outer beach in the area is dangerous and unfit for swimming by the public.” Vonnegut countered, “He had a point . . . A frolic in the big rollers of the open Atlantic can be like playing middle linebacker against the Cleveland Browns. And the water is frequently so cold . . . that a quick dip can be like falling overboard on the run to Murmansk. Only children seem able to stand such punishment for long. They can stand it all day.” Vonnegut appreciated getting information about “birds and erosion and fish and bayberries,” but enjoyed more seeing visitors “whoop and holler . . . gasp and sputter and laugh as the waves slam them silly . . . [they] fish without a worry in the world . . . [they] walk for miles, and . . . walk alone.”

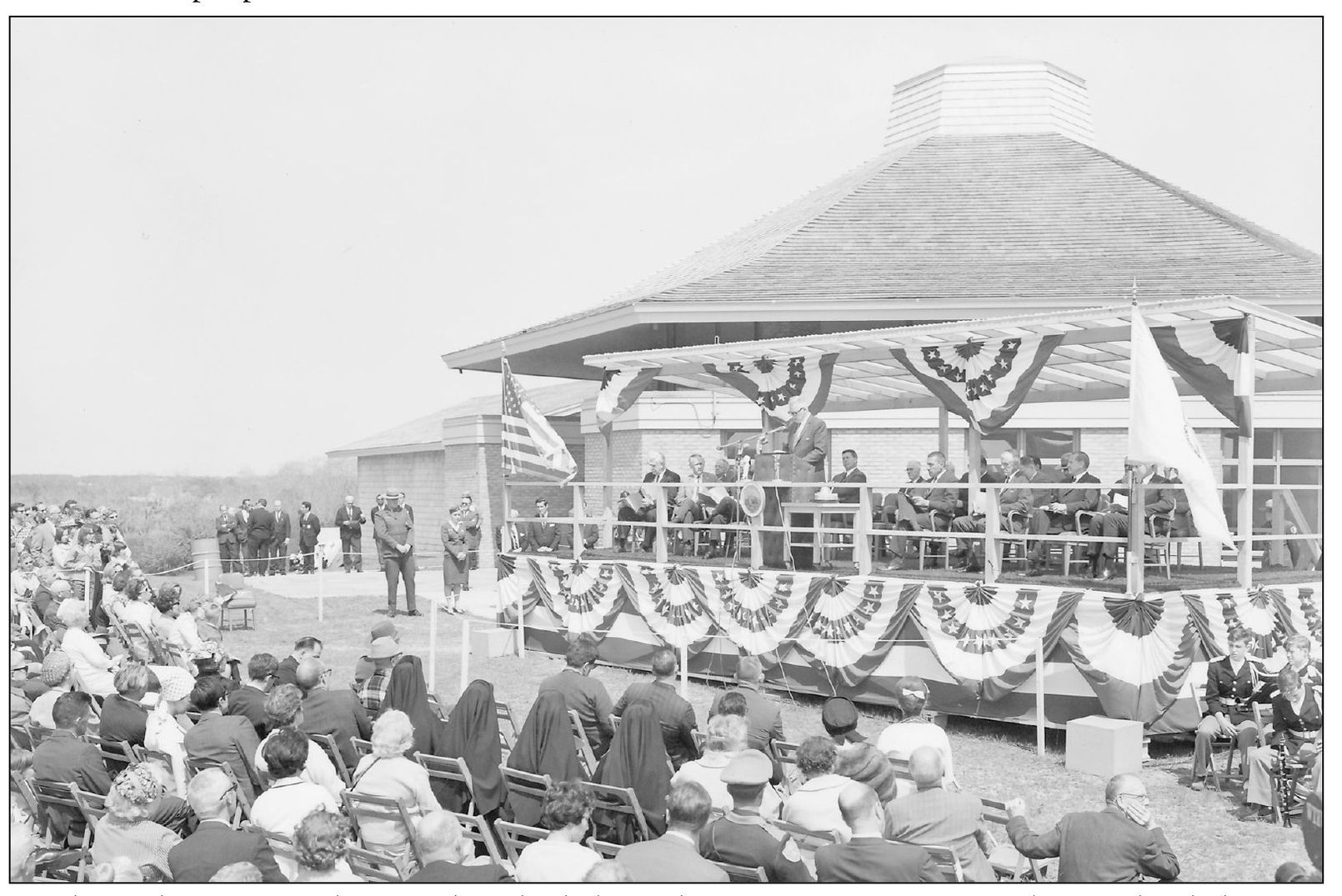

On Memorial Day weekend in 1966, Cape Cod National Seashore Park was dedicated. The front-page story in that day’s New York Times announced, “The first land the Pilgrims sighted before landing at Plymouth 346 years ago was dedicated today as Cape Cod National Seashore . . . The dedicatory exercises were held on the lawn outside the newly dedicated visitors’ center . . . situated on a knoll overlooking Salt Pond and beyond to Nauset Bay . . . Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall [pictured above] declared: ‘We who have chopped and mined and built and machined our way to wealth and power now grope out from our cities, puzzled, yearning, almost wistful, for something we cannot forget. Beyond the noise and asphalt and ugly architecture we yearn for the long waves and beach grass; we see white wings on morning air, and, in the afternoon, the shadows cast by the doorways of history.”

Sen. Edward Kennedy is seen here introducing Sec. Stewart Udall at the CCNS dedication. Also taking part were Sen. Leverett Saltonstall and Rep. Hastings Keith, both Massachusetts Republicans, who cosponsored one version of the park bill. Luther Smith, chair of the Eastham Selectmen, spoke for the selectmen of the six towns in the park.

At the dedication, Udall joined other speakers in tributes to President Kennedy, pictured here signing the legislation that created CCNS on August, 7, 1961. It was part of Kennedy’s philosophy, Secretary Udall said, “that a father should be able to show his children—all children—the wonders of nature he himself had known. The marshes, the seascapes, the sea itself should remain inviolate for all time for all men.”

Gov. John A. Volpe (right) presented the deeds of the Province Lands Reservation to George B. Hartzog Jr., director of the National Park Service. This protected the Province Lands forever, a place known as the second-oldest common lands in the nation, second only to Boston Common. About 2,000 people attended the ceremonies.

Much of what Henry Thoreau cherished about the Outer Cape 100 years before the dedication of the seashore is still in evidence within the vastness of the park. Thoreau wrote, “Though once there were more whales cast up here, I think that it was never more wild than now. We do not associate the idea of antiquity with the ocean, nor wonder how it looked a thousand years ago, as we do of the land, for it was equally wild and unfathomable always.”