Eight

RANGERS AND SPECIALISTS IN THE FIELD

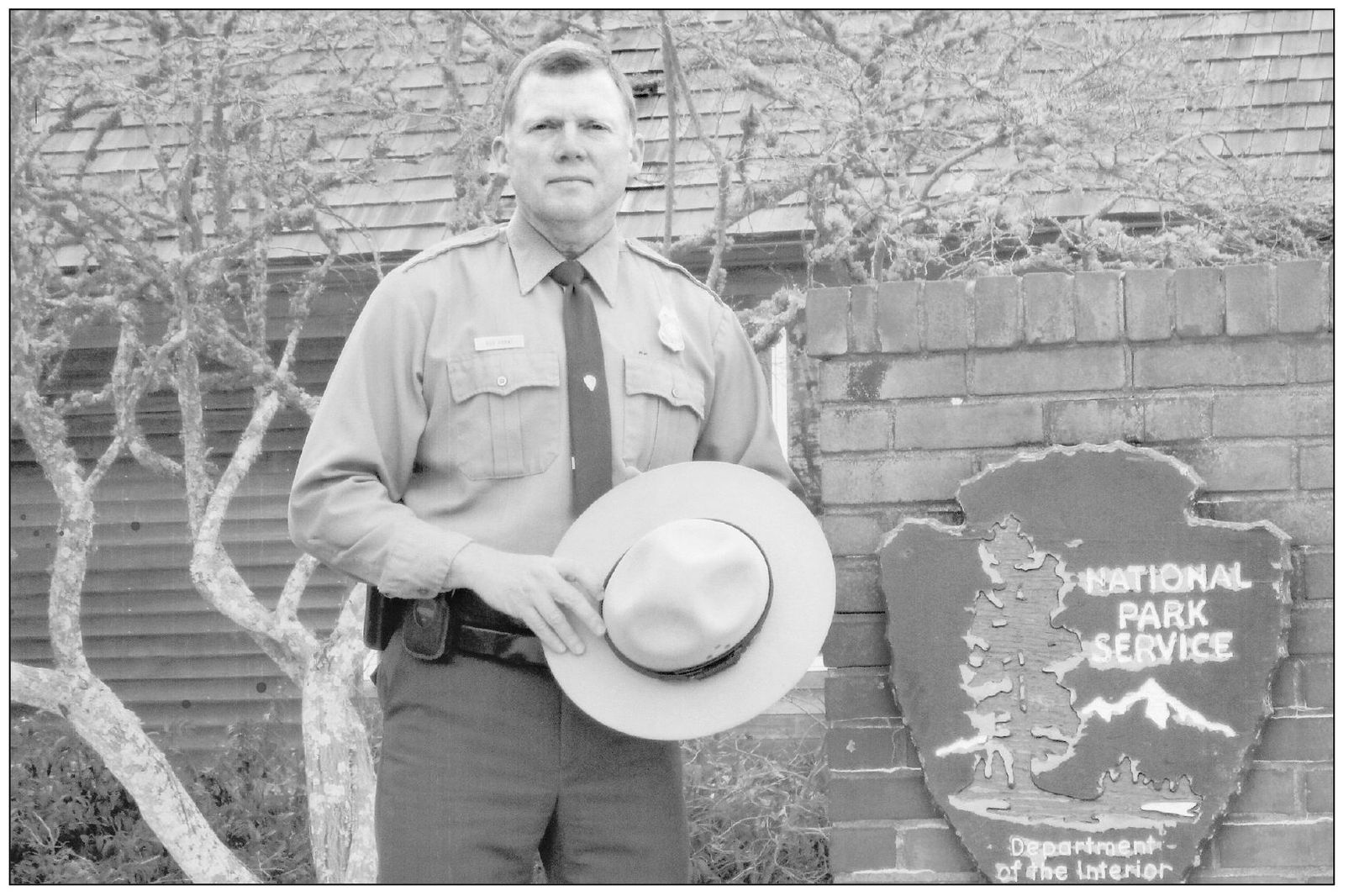

In early 2009, Bob Grant was selected as the chief ranger of Cape Cod National Seashore. Grant served as the seashore’s South District ranger working out of the Nauset Ranger Station and before that, as a park ranger at the Race Point Ranger Station. “The men and women in the flat hats,” as Grant affectionately calls them, are responsible for the safety of more than four million visitors per year.

Chief ranger Bob Grant traces the origins of his rangers back to the U.S. Cavalry, sent into Yellowstone Park to protect the land from poachers of animals, minerals, and timber. The rangers and specialists of Cape Cod National Seashore are a dedicated team, highly trained to conserve and protect Cape Cod National Seashore. (Photograph by Jack Finley.)

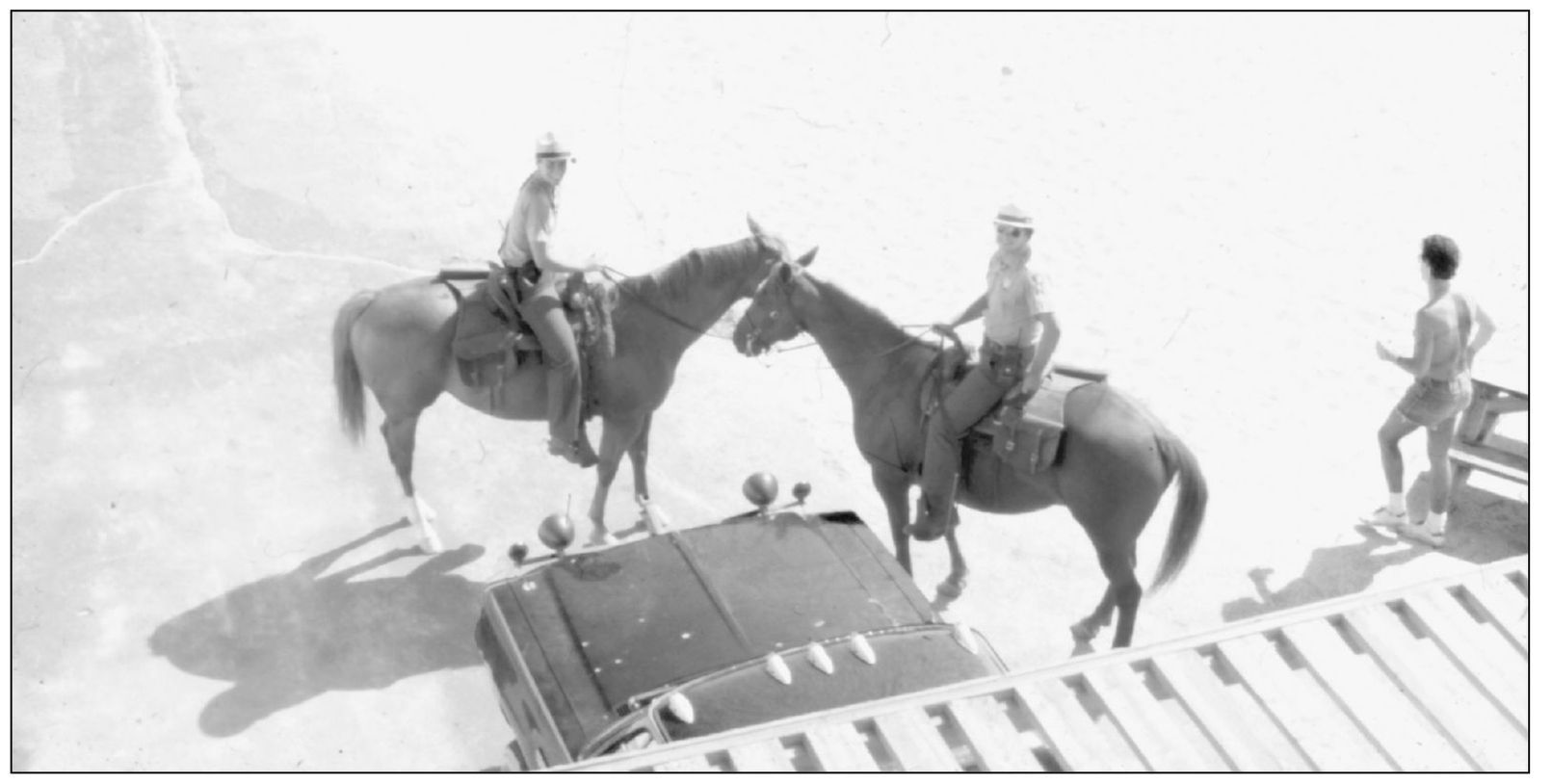

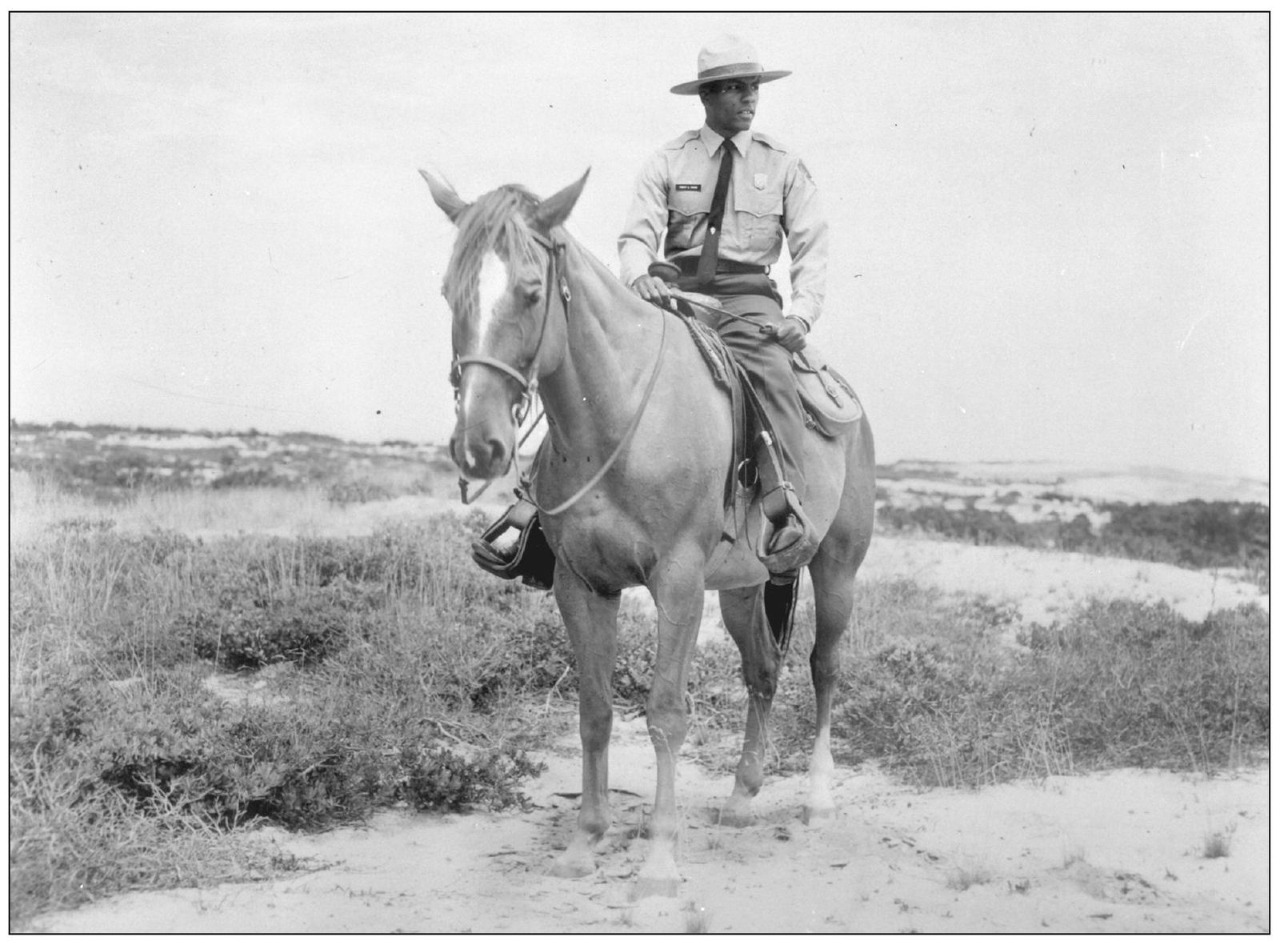

More than 130 years ago, Yellowstone became the first national park. By 1916, some 35 other parks and monuments had been set aside, leading Congress to create the National Park Service. In the 1960s, two trained horses from Yosemite were donated to CCNS, initiating the national seashore horse patrol (no longer active). Park ranger Robert Tignor is seen here in 1966. The horses adapted easily for patrol along the beaches and in remote areas closed to vehicle access.

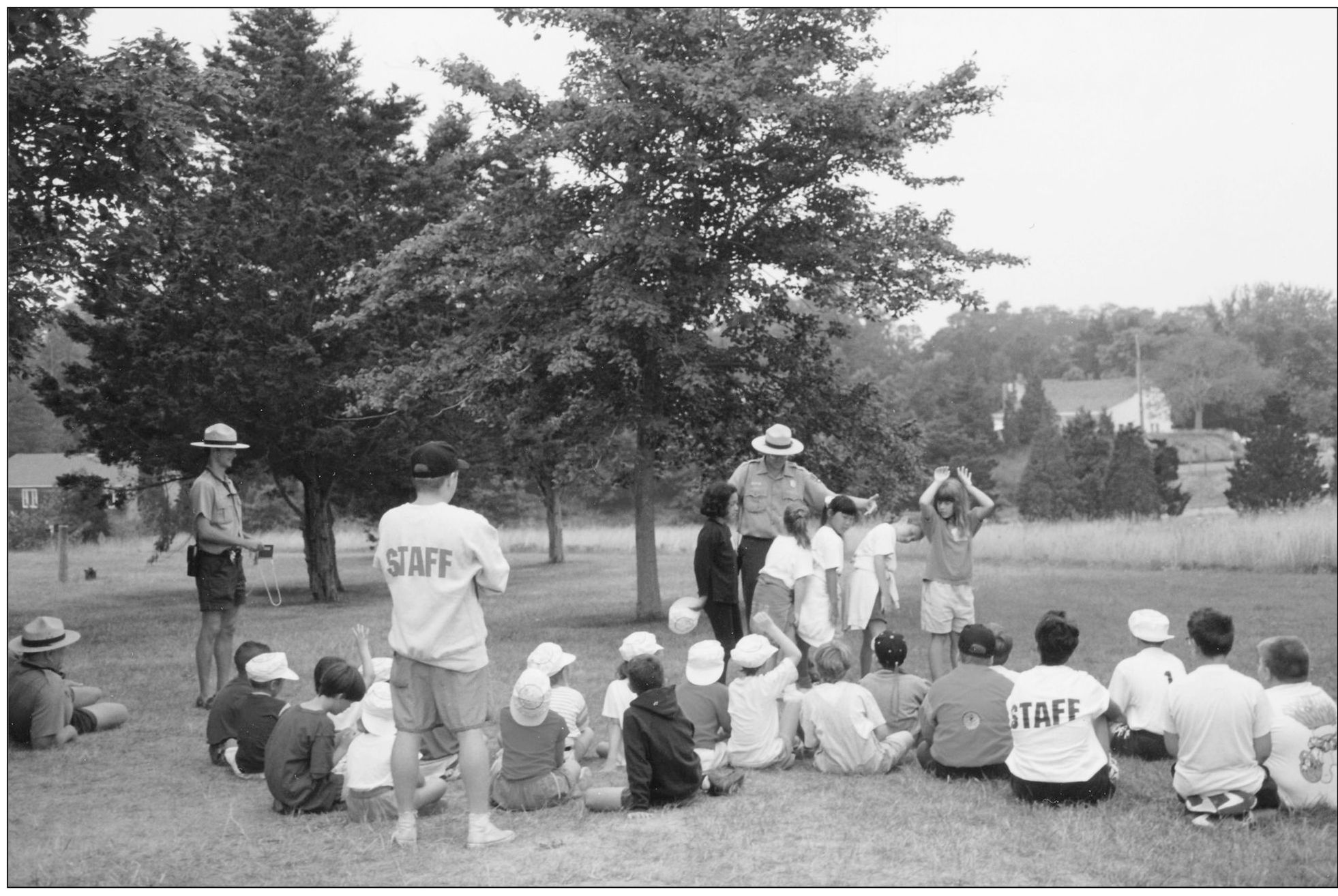

Chief Ranger Grant began his career with the National Park Service in 1976 at Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina and Tennessee as an interpretive ranger and a backcountry ranger for three summers. After graduating from college, Bob was hired as a year-round ranger, park medic, and supervisory park ranger. He developed a strong background in several operations, including law enforcement, EMS, search and rescue, wildland fire, backcountry, and bear management. Except for bear management, each of Bob’s skills is utilized at the seashore. He says that along with the millions who visit the park each year come the social problems of their home environment. This photograph shows rangers leading a drug education program in 1993. Most park rangers are trained in law enforcement, hunting and game law, fire protection, and as medics and EMTs. They work closely with the law and safety agencies of the surrounding Cape Cod towns. Thus Bob reports that the crime rate within the national seashore is “staggeringly low.”

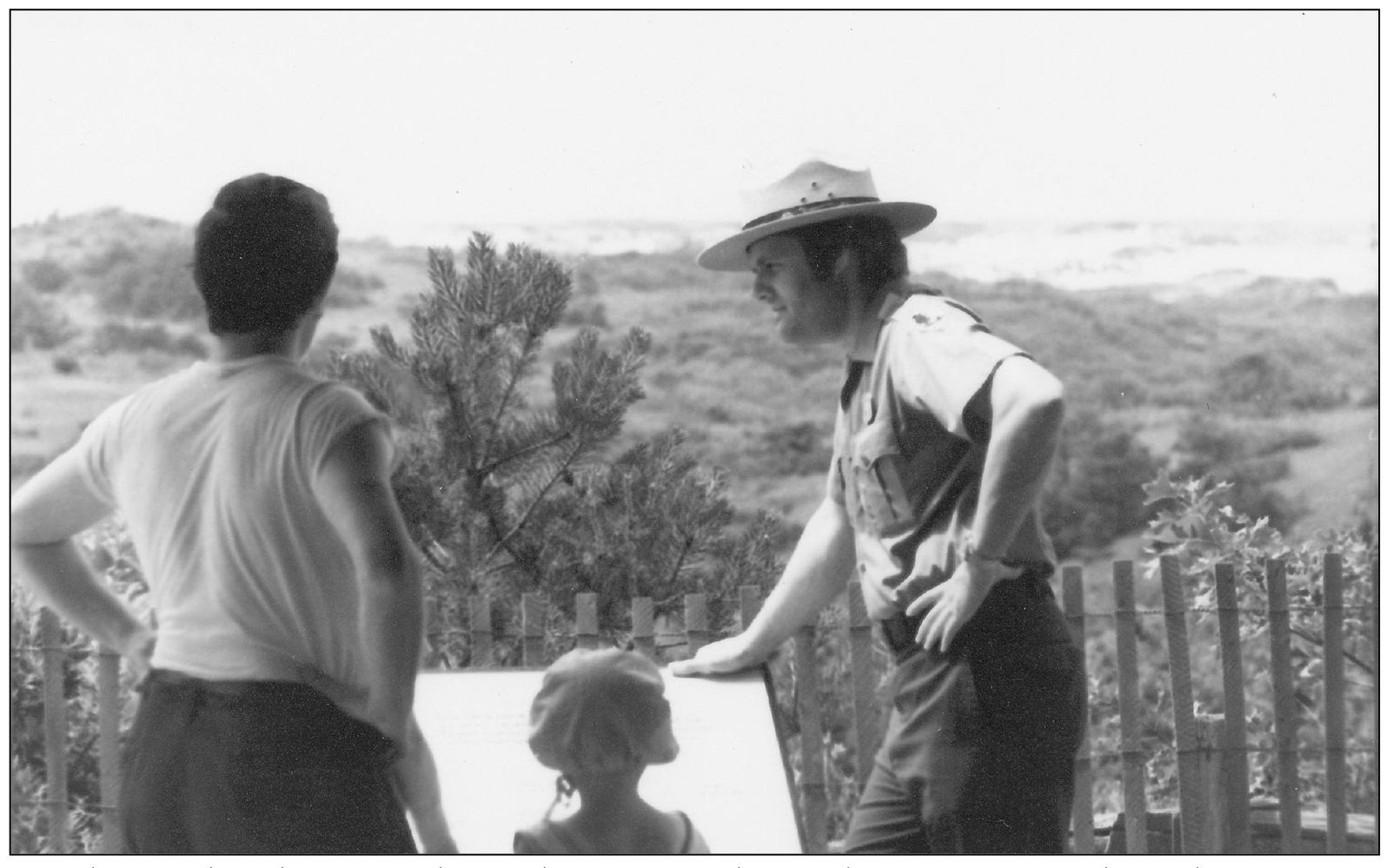

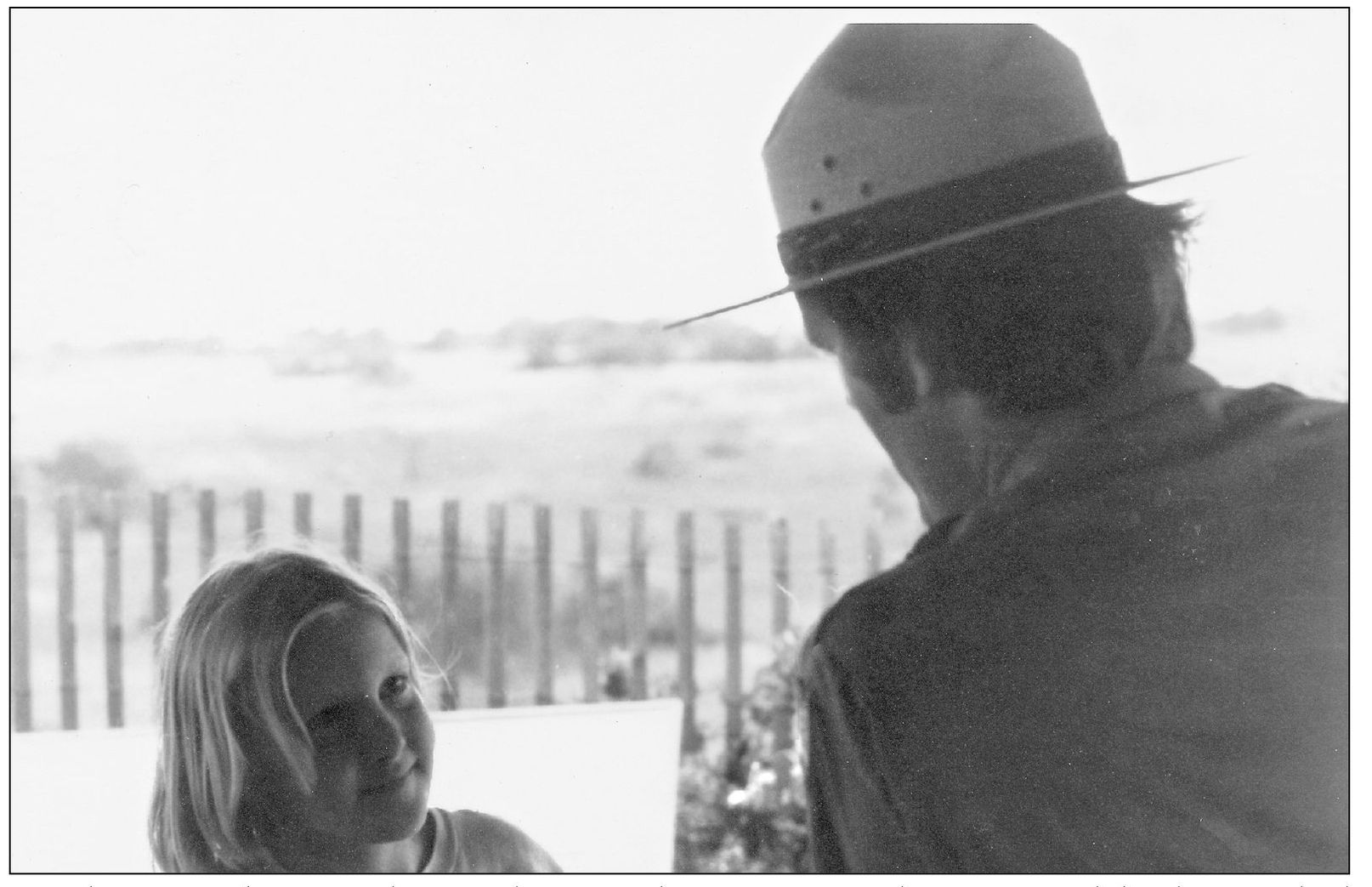

The park rangers, environmentalists, natural resources management staff, and other specialists have a dual function: to protect the Cape’s natural environment, and to protect the people who enjoy it. Thus when 700 gray seals began spending summers in 2006 at Head of the Meadow in Truro, Chief Ranger Bob Grant, above, saw to it that the seals were protected from visitors and visitors were protected from the seals.

In January 2008, a storm washed up a 60-foot section of a wooden shipwreck at Newcomb Hollow Beach in Wellfleet. Built in the 1800s, this type of vessel transported goods along the New England coast and beyond. National park rangers welcomed visitors to educational talks at the site. One of the seashore’s greatest assets, according to Chief Ranger Grant, is a public who enjoys seeing shipwrecks and seals and becomes invested in the welfare of the park.

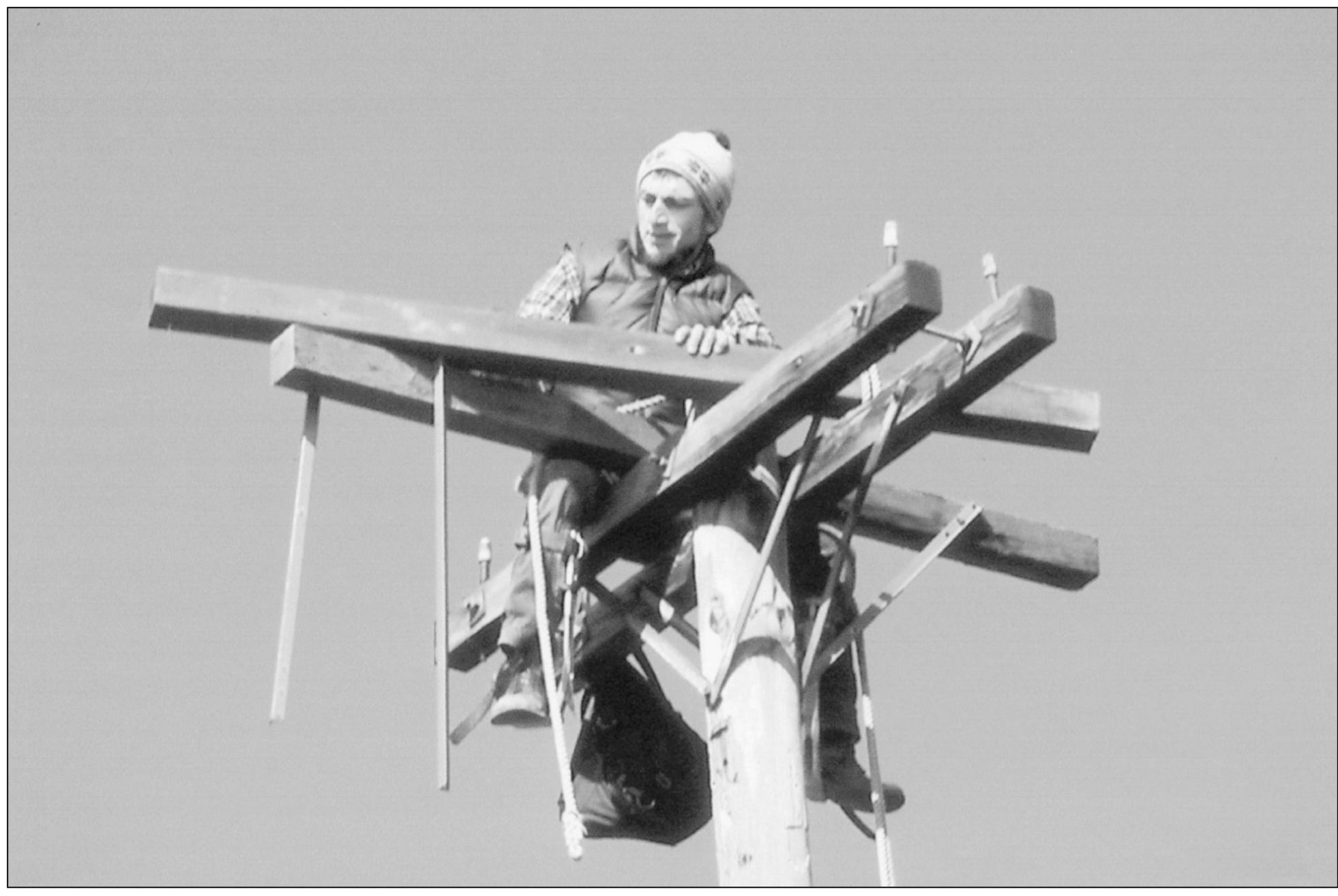

Ecologist John Portnoy was one of the park’s many specialists. Among his many projects, he built this osprey nesting platform on Great Island in Wellfleet in 1980. Portnoy, who was with the seashore from 1979 to 2008, says, “I think that the seashore as a management agency has gotten better at achieving its mission of preservation and sustainable public use over the 30 years of my tenure. Improvement has paralleled the increase in ecological theory and scientific literacy among politicians, park managers, and the public (not always in that order). Also, I think that NPS managers have gotten more proactive and bolder in protecting and restoring natural resources, and much more enthusiastic about working cooperatively with the ‘Seashore Towns.’ It’s much more accepted today that NPS can’t protect park resources at a place like CCNS without paying close attention to, and keeping involved in, what happens outside the park boundaries.”

The rangers and other experts at the national seashore offer an extraordinary number of activities for every variety of visitors. For example, Dan Meharg and Hortense Kelly led a Christmas program at the Penniman House in 1993. There are programs about life on Cape Cod in the 1800s; historical lifesaving methods using signal flags, Morse code, and lighthouse signals; and historical operations of the Old Harbor Life Saving Station. There are canoe and kayak trips; programs on the botany of dunes, tidal restoration, oyster habitats, native life on the Cape, food-and candle-making at the 1700s Atwood Higgins House; and programs on shipboard activities, whaling, and scrimshaw at the Penniman House, to name just a few.

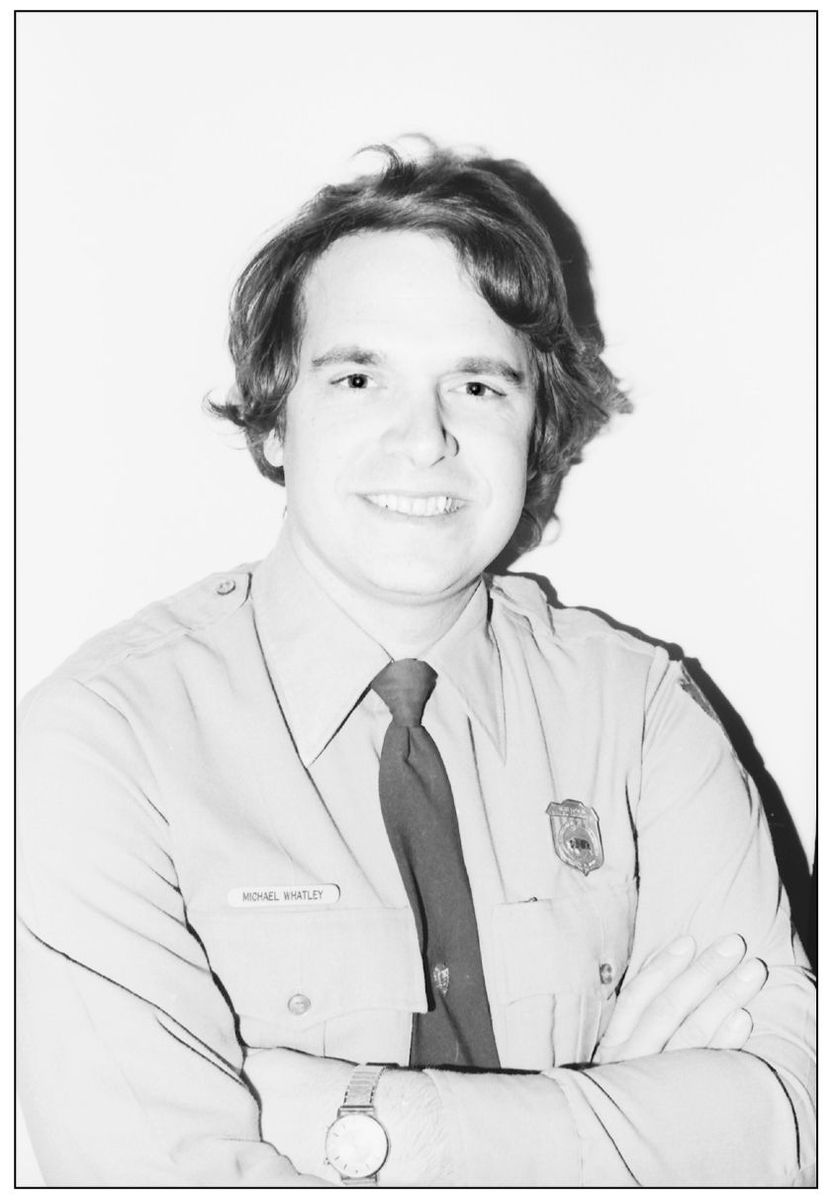

For 24 years, Mike Whatley was an essential part of the national seashore team. He served as park historian for 15 years, and as district interpretive supervisor, then branch chief for public information. He recalls that, “The Penniman House was boarded up when I first came on duty in 1977; our crew got permission to open it up. It is now an active, fun place to visit. We got the Three Sisters [lighthouses] opened up too.”

“The national seashore,” says Mike Whatley, “is a time machine. It saves a history that goes from prehistoric Native Americans, to European explorers, to the Mayflower passengers, to Lighthouses and Lifesavers, to Thoreau, to Marconi and wireless. And it is an equally impressive natural treasure trove. The old Coast Guard Station in Eastham is a great vantage point, and witnessing the Great Storm of 1978 [seen above] was simply amazing.”

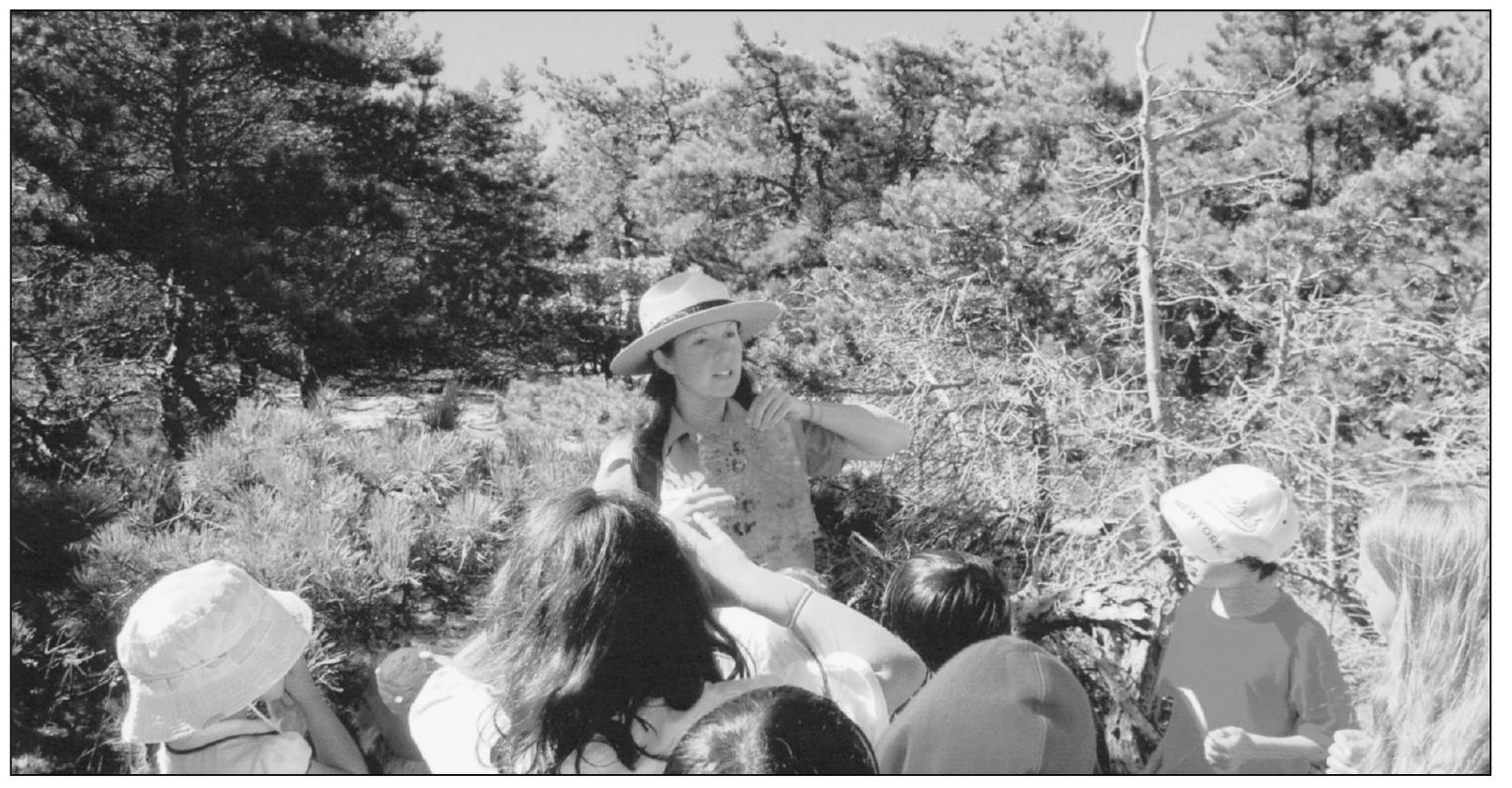

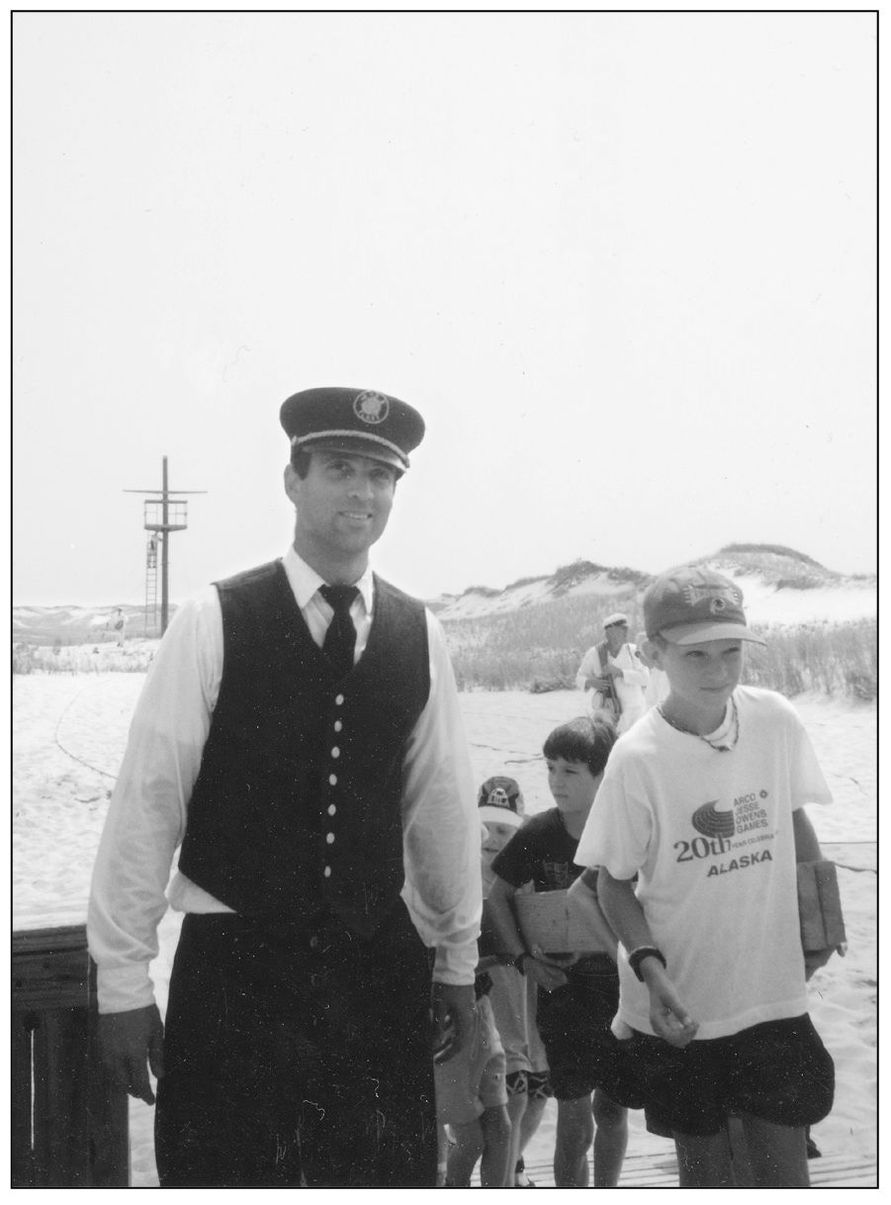

The National Park Service is committed to helping young people understand the special qualities of the national seashore and the importance of developing a stewardship ethic for its future. The seashore’s junior ranger program is for kids between the ages of 5 and 12 and takes at least two days to complete. Junior rangers join park rangers like Katie Finch (above) to look for seals, tour historic lighthouses, and learn the natural history of the seashore.

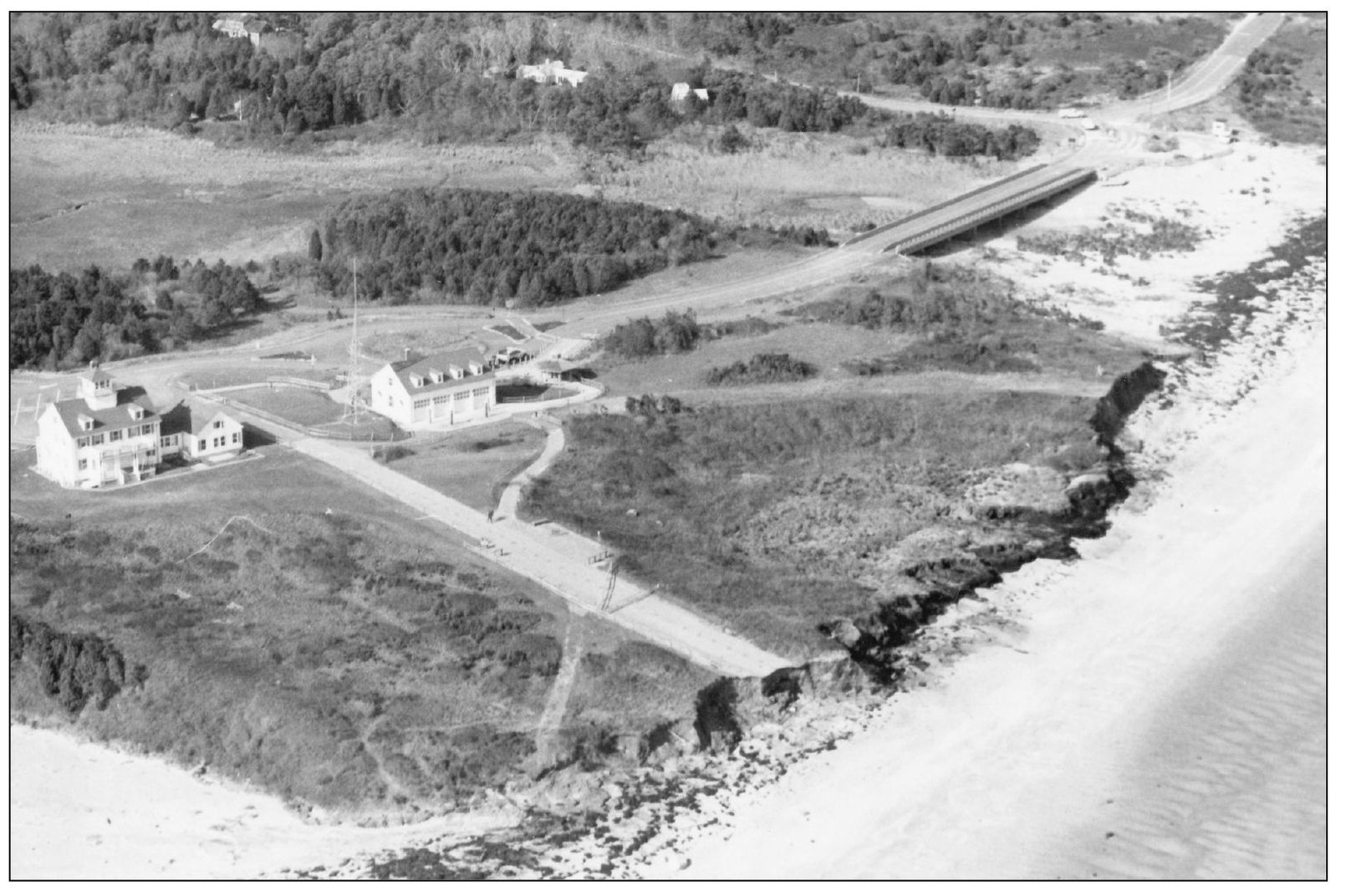

The seashore’s residential environmental education program (NEED) offers educational groups an opportunity to experience the natural and historical wonders of Cape Cod. Groups come from a wide range of areas, some as far away as Ohio, Colorado, and Virginia. Groups with special-needs clients or from inner city environments are encouraged to participate. The program, led by education coordinator Barbara Dougan, is housed in the former U.S. Coast Guard station at Coast Guard Beach (above).

David Spang has the extraordinary distinction of having been a ranger at the park since 1963, the first year the national seashore was open to the public. He recalls, “The first season, I was sometimes the only uniform on duty on the late season weekends. Not a very large staff at the beginning. The HQ was at the Coast Guard building in Eastham, and a couple of the barracks at Camp Wellfleet were used as indoor facilities during bad weather.”

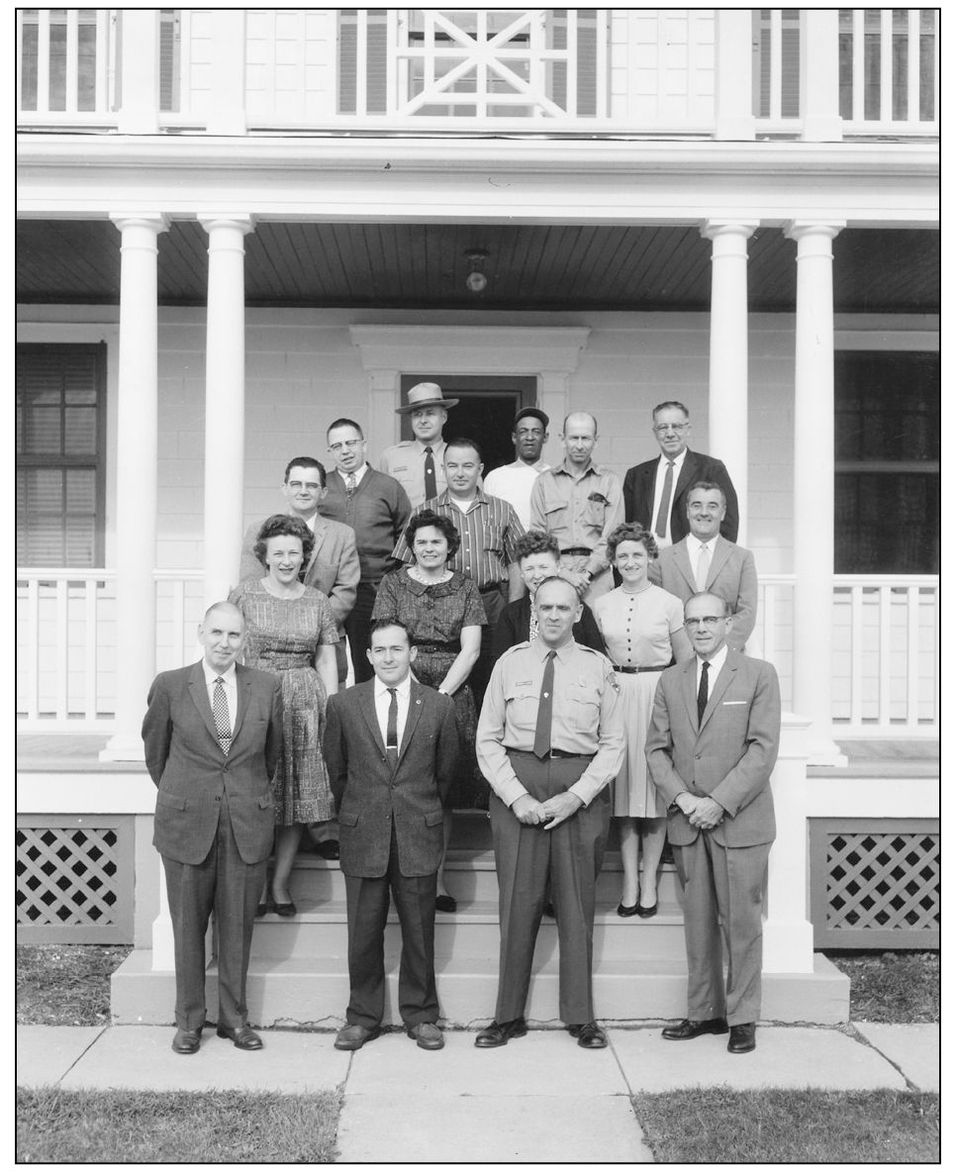

“Many of my favorite memories,” says David Spang, “come from the early years sitting in Tommy Gilbert’s kitchen putting together the design for the seashore emblem while his wife, Patsy, painted it. [Or] Meeting Henry Beston when he came back to the Cape for the first time since writing The Outermost House in order to turn over ownership to Wellfleet Audubon.” Pictured is the first CCNS staff, with Supt. Robert F. Gibbs third from left.

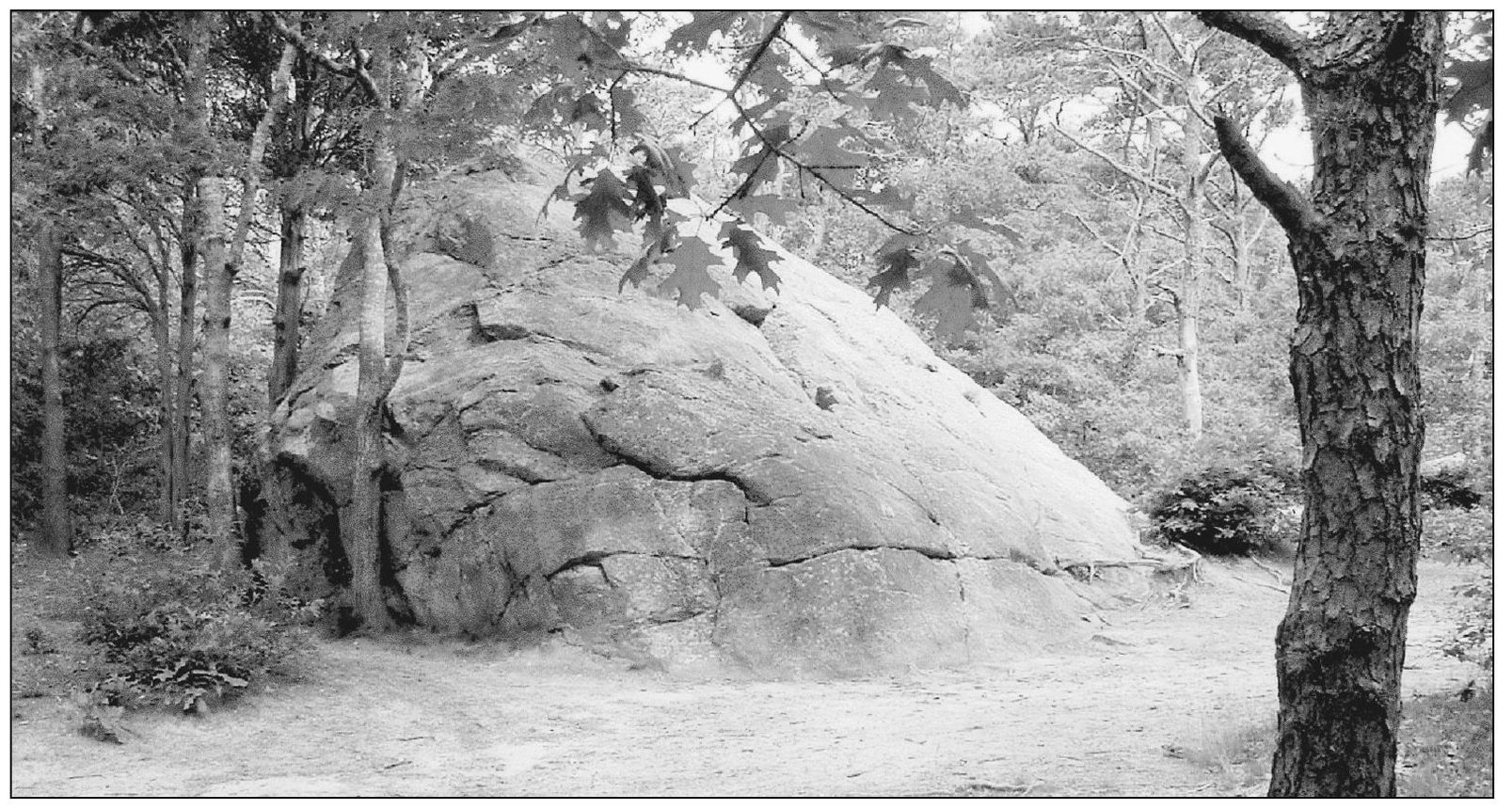

David Spang recalls helping scientists probe Nauset Marsh to age date salt marsh peat, and matching Champlain’s map to the present only after thinking to correct for the drift of the North Pole. He particularly enjoyed finding a boulder to represent the erratics left after glacial retreat. It came from Nauset Heights and is still at the visitors center. The best example, Doane Rock (pictured above), was much too large to move.

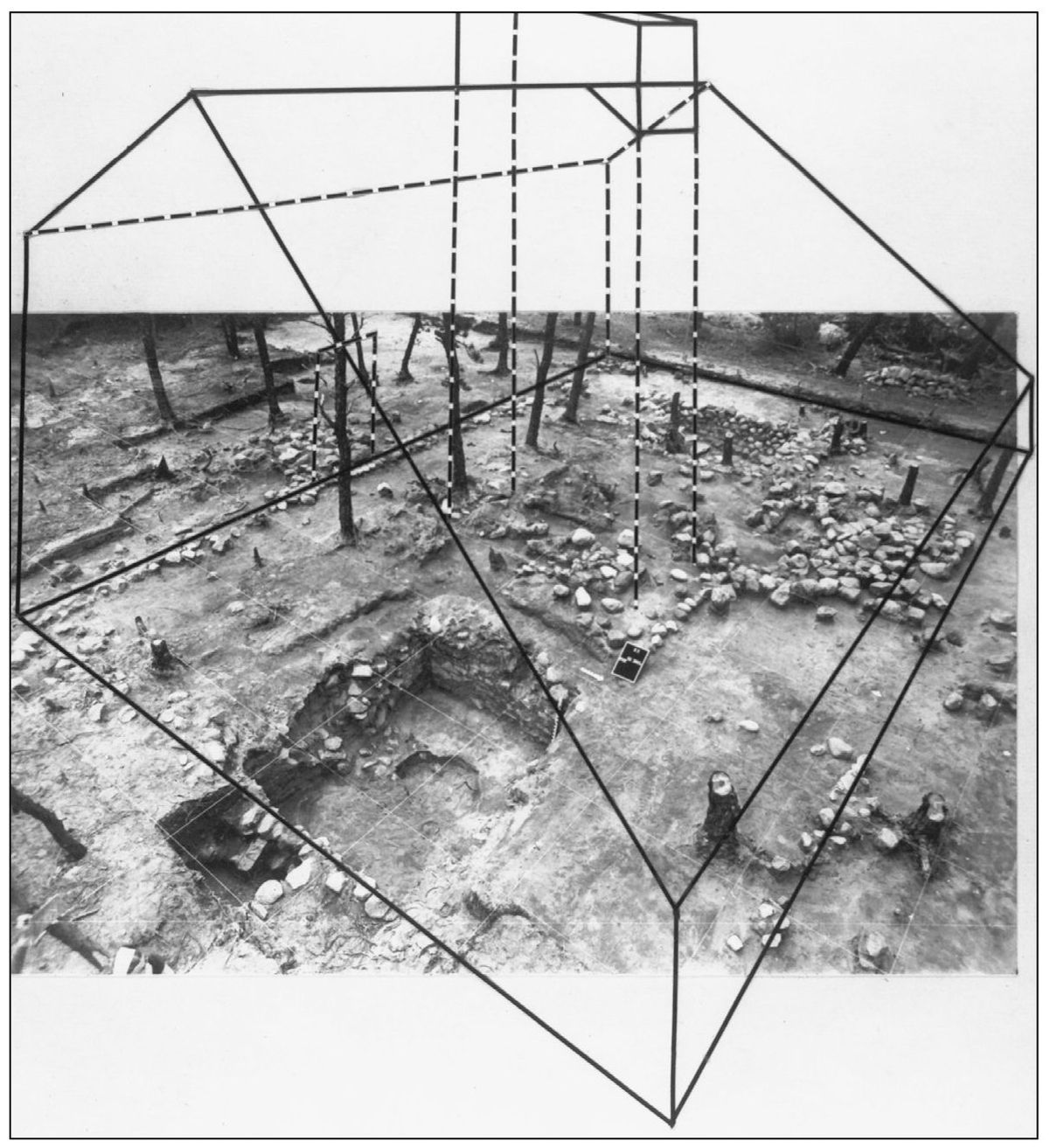

David Spang recollects working with seasonal historian Ralph Linwood Snow for several years. “He and I planned the trail on Great Island in Wellfleet and [viewed] the site of the original Smith’s tavern.” Here is an outline of Smith’s Tavern superimposed over the site after a dig by archeologists from Plimoth Plantation. Spang and Snow developed the original trail in Fresh Brook Village where Snow’s ancestors had settled.

David Spang spent all of his teaching breaks in the winter of 1963–1964 on his hands and knees cutting through the Bear Oak forest at White Cedar Swamp, above, to create the trail. “One of the trunks,” he says, “was only a couple of inches across. It measured out at about 75 years of age and had been part of the Lilliputian forest of Thoreau’s walk.”

David Spang, pictured at right in the first row, recalls, “The first female ranger in the park service was Melinda Melby. At first they [female rangers] looked like stewardesses on a plane. The requirements of a skirt, short heeled shoes, and silk stockings just didn’t work out on walks in the dunes and woods . . . someone finally came up with the bright idea that maybe they should be dressed like all the other rangers.”

Early park ranger David Spang tells of the opening of the Province Lands bike trail in the 1960s, the first in a national park: “I saw Dr. Paul Dudley White, Eisenhower’s physician, finish before anyone else, even though he was in his 70s. He was one of the early promoters of bike riding for good health.”

David Spang said, “I started seasonal time on the Cape in 1939, before any real development had occurred. Most of the roads were still unpaved—electricity hadn’t arrived in my part of Mashpee. CCNS has meant a way for me to raise my family with access to the sea and sand that I had in my youth. My four children have that special feeling about the Cape that my wife and I have, and are now bringing their kids here as often as they can.”

Suzanne Haley, South District interpreter, has been with Cape Cod National Seashore since October 1990. CCNS is, she says, “the place where one can find solitude and serenity . . . or be thrilled by the forces of nature.” Sue recalls arranging holiday celebrations at the Atwood Higgins and Penniman houses for 10 years. “[They were] all-hands event for the interpretive staff and volunteers.”

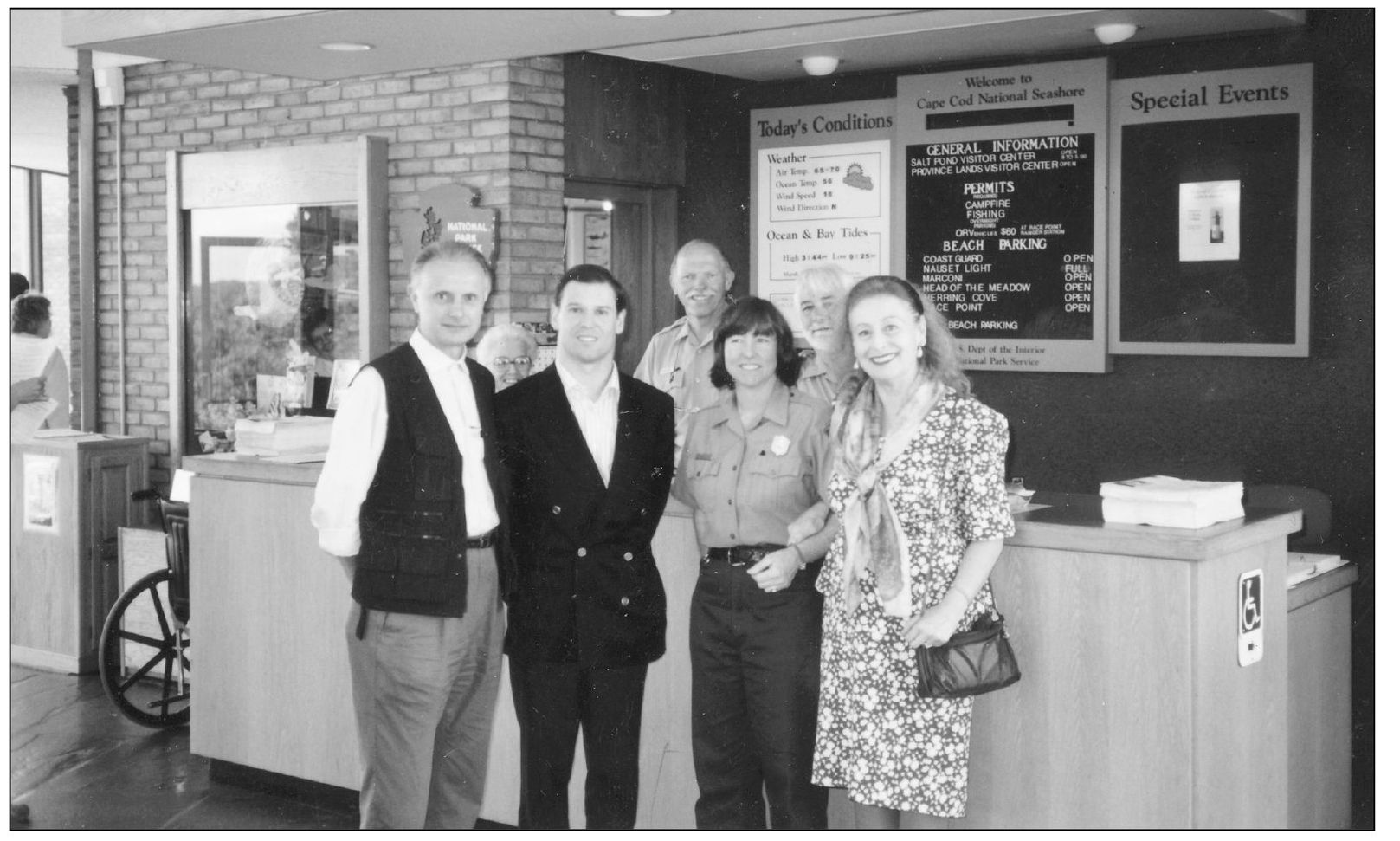

Sue Haley’s fondest memory is “getting kissed on the cheek by Princess Elettra Marconi (Gugliemo’s daughter) on Marconi Day, 2003.” Princess Elettra is on the far right next to Sue Haley. Sue’s oddest memory is of policemen surrounding her while she hovered over a dolphin carcass with a butcher knife behind a shed as she collected a bone specimen. The police were trying to determine whether she was working on a marine mammal or a mammal of the two-legged variety.

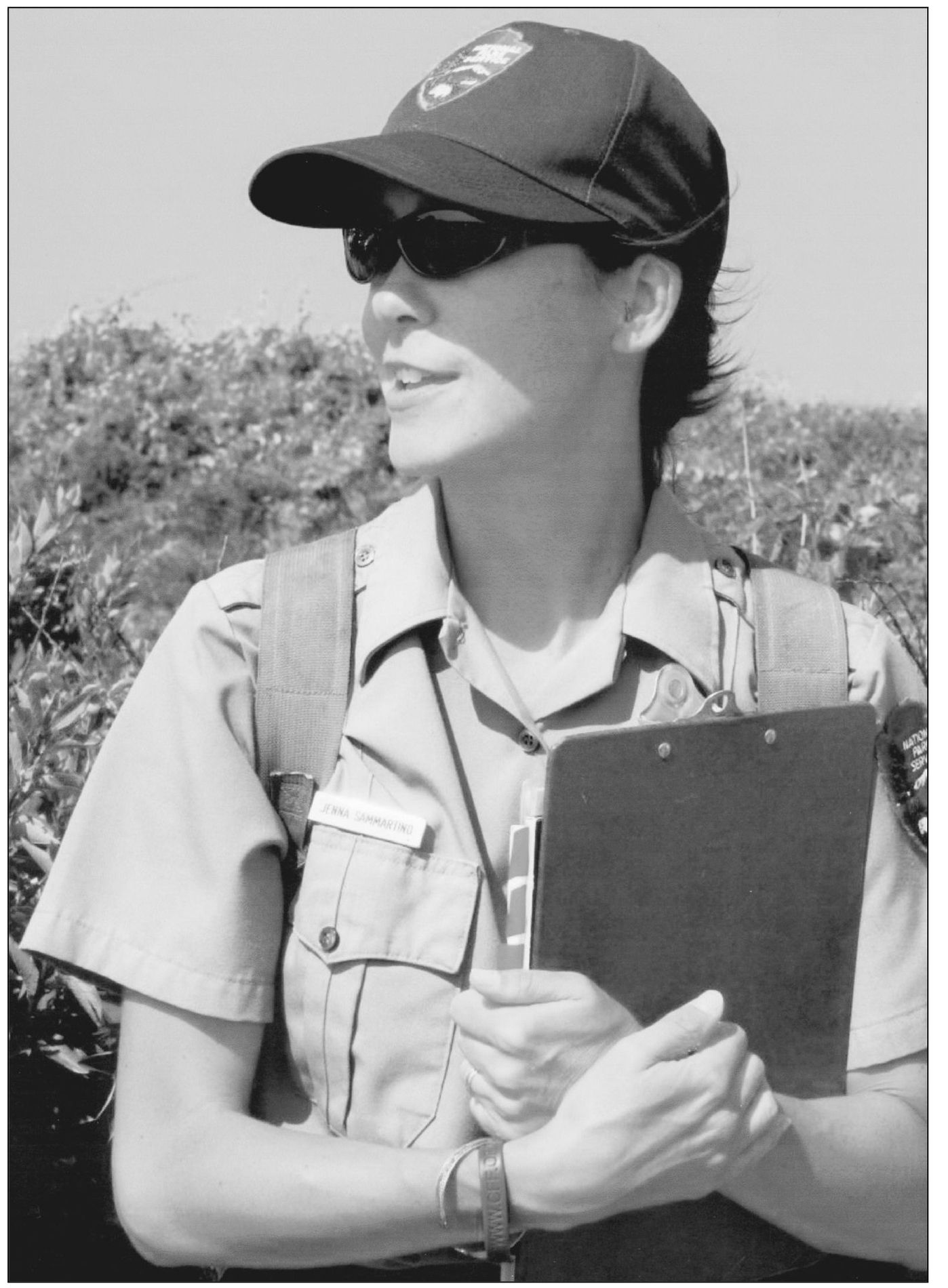

Jenna Sammartino has been with CCNS since 2004: “One memory that stands out for me occurred my first or second winter at the park. A commercial fishing boat had wrecked off Coast Guard Beach and reports were that one of the crew was missing. The Cape fishing community is pretty tight-knit, and soon my husband and I were among several others scanning up and down the beach for the missing man. Our law enforcement staff was on the beach, the local harbormasters were on the water, and the Coast Guard helicopter kept doing flyovers. It was freezing cold, we were out there for what seemed like hours, and I remember my husband saying, ‘If it was me out there, I’d want to know no one was going to give up until I was found.’ So we kept our binoculars trained on the waves . . . Being at Coast Guard Beach, with the old white Coast Guard building in the background, I couldn’t help but think about the days when men from the U.S. Life Saving Service patrolled the beach and this kind of thing happened all the time.”

Jenna Sammaratino recalls seeing a fishing boat wreck a few years ago off Coast Guard Beach. She noticed the Coast Guard helicopter had stopped searching. It turned out, she says, that “the fisherman was alive and well, but the circumstances were the best part of it. Someone walking past the Coast Guard building had noticed that one of the basement windows was broken. The missing man had swum to the beach and then made his way to the building, where he broke in, took a hot shower and fell asleep! I just thought it was so amazing that all these years later, that old building was still doing exactly what it had been built to do—save the lives of shipwreck victims.” (Below, courtesy of William Quinn.)

When Bill Burke (left) began as a seasonal ranger in 1984, his first reaction was, “You’ve got to be kidding me—this place is drop-dead gorgeous. This is a dream job.” Early on Burke led breeches buoy Life Service demonstrations. Since 2000, he has been park historian and cultural resources program manager, responsible for 76 historic structures, 250 archeology sites, 500,000 museum objects, and major cultural landscapes like Fort Hill.

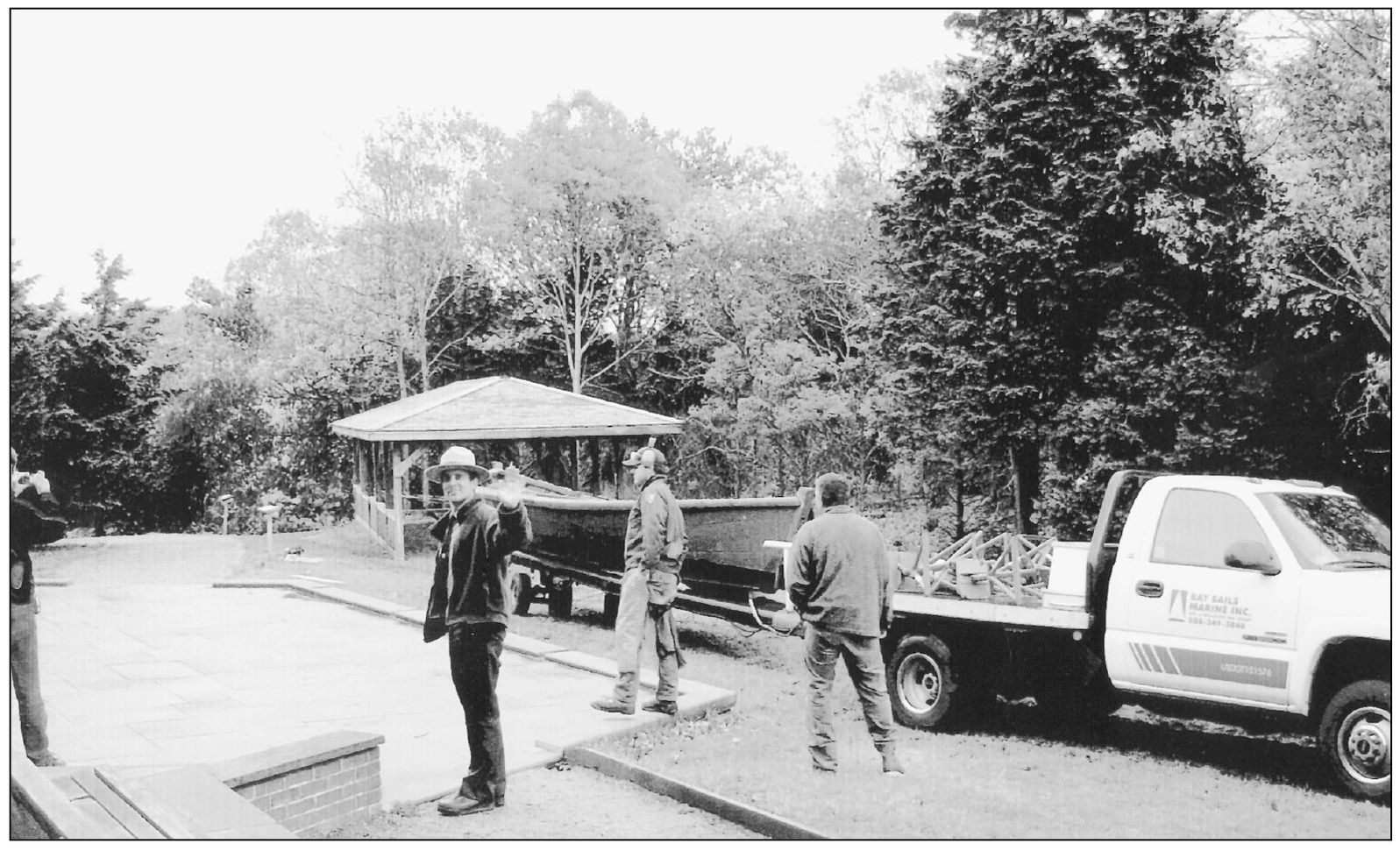

“Having seen and worked in several parks,” Bill Burke says, “this one is special because it’s relatively small, intimate and fun . . . it is still easy, despite the summer crowds, to find your private place. I take what residents say very seriously and am humbled to be one of the ‘holders’ of that local heritage.” Here Bill takes part in the installation of a mid-19th century hay barge at the visitors center.