INTRODUCTION

Restless Cape Cod has been so blown and carved by wind and water that the peninsula of sand we walk today is, literally, not the one of a thousand, a hundred, or even 10 years ago. But the spirit is the same. There is one reason, and one reason only, that we can still say of Cape Cod and the sea, as Thoreau did, “it was equally wild and unfathomable always.” And that is because of the noble experiment of Cape Cod National Seashore.

If there was one moment when that spirit was nearly lost, it was in 1960. The movement to create a national seashore on Cape Cod had been brewing—sometimes contentiously—since 1939. World War II interrupted such thoughts. Postwar, in 1955, the New York Times announced, “Speedway to the Tip of Cape Cod. A superhighway extending from the Cape Cod Canal at the base, to Provincetown at the tip of the Cape . . . will open up new scenic vistas to the tourist this summer and substantially cut down driving time to Cape towns.” Then in 1960, the Mel-Con development company bought magnificent Fort Hill in Eastham and began to divide the land into 33 lots and lay out roads. This one event, when brought to the attention of America, brought the political and cultural sea change that saved Cape Cod.

At a December 16, 1960, meeting in Eastham, Charles Foster, state commissioner of natural resources, urged officials to take action, noting that Eastham was “within a day’s drive of 50 million people—people who, park or no park, are already seeking this last stretch of unspoiled shoreline in unprecedented numbers.” President-elect Kennedy was quoted as saying, “Cape Cod offered one of the last remaining chances to preserve a major recreational area from ultimate destruction.”

Competing bills began to appear before Congress, but little was resolved. In April 1961, it was clear that the only way to break through the fog of inaction was to organize land and air tours of the Cape for officials and townspeople to see for themselves what was at stake. Sen. Leverett Saltinstall’s assistant Jonathan Moore said, “It was a glorious trip. We flew low over Nauset Marsh and landed at one point on Fort Hill, and we were standing there, arguing about whether Fort Hill should be in the park or out of the park. It was still up for grabs. A subdivision had been laid out, and there were even some stakes outlining a couple of homes.” Sen. Alan Bible said, “That decided it for me!”

On August 7, 1961, seven months after becoming president of the United States, John F. Kennedy signed the bill creating Cape Cod National Seashore. “This act makes it possible,” he said, “for the people of the United States through their government to acquire and preserve the natural and historic values of a portion of Cape Cod for the inspiration and enjoyment of people all over the United States.”

The Berkshire Eagle of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, noted: “A great public project that seemed almost hopelessly visionary when first proposed five years ago became a reality in Washington yesterday . . . establishing a 26,666-acre national park on the outer shore of Cape Cod. The bill can probably be labeled the finest victory ever recorded for the cause of conservation in New England.”

More than that, it was a breakthrough in the cause of U.S. preservation. Never had a national park been created in a place so extensively inhabited. Others, like Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon, had been carved out of publicly owned wilderness or donated lands. Cape Cod National Seashore (CCNS) proposed to conserve a fragile, still wild place that overlays six established towns. It set up an entirely new mechanism, the first citizens’ advisory commission, to help in the management of lands, and it authorized funding for considerable private land acquisition. This became known as the Cape Cod Model. Today CCNS is one of 10 national seashores, including Cape Hatteras, Cape Lookout, Point Reyes, Assateague Island, Canaveral, Cumberland Island, Fire Island, Gulf Islands, and Padre Island.

Cape Cod is unique among them. Conrad Aiken wrote in 1940, “Nature and layering of culture and history are the most essential elements of the Cape Cod character. For hundreds of years, Native Americans, the Pilgrims, fishermen, sailors, poets, dancers, whalers, playwrights, writers, photographers, journalists, politicians, and visitors from all over the United States and the world have traveled to or settled on this small peninsula.”

The rich lore of the past is evident everywhere. There are reminders of the Pilgrims in place names like Corn Hill, Pilgrim Springs, and First Encounter Beach. Stories of shipwrecks, like the wreck of the pirate ship Whydah, come alive when even today pieces of ancient shipwrecks wash up on the beaches. The landscape still evokes stories of creaking windmills, lighthouses, and wild cranberry bogs. Stretching so far out to sea, the Cape became a focal point for early communication with Europe. It is here that Marconi first sent wireless messages to England, here that the French Cable Station brought news of Lindbergh’s flight in 1927, and the German invasion of France in 1940.

The pantheon of writers and artists drawn to work here is astonishing: Henry David Thoreau, John Dos Passos, Mary McCarthy, Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, Mary Heaton Vorse, Henry Kemp, Henry Beston, Anne Sexton, Mary Oliver, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Norman Mailer, Elizabeth Bishop, Stanley Kunitz, Marge Piercy, Annie Dillard, Edward Hopper, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Henry Hensche, Hans Hoffman, Ben Shahn, and Robert Motherwell are only a few of those who have created a rich tradition of the arts on Cape Cod.

Though this landscape has been long inhabited, it has never been domesticated. Over 450 species of amphibians, reptiles, fish, birds, and mammals, and myriad invertebrate animals depend on the diversity of upland, wetland, and coastal habitats found in Cape Cod National Seashore. The park provides habitat year-round, particularly during nesting season, migration, and wintertime. Wildlife here includes the familiar gulls, terns, and waterbirds of beaches and salt marshes and a great variety of animals that inhabit the park’s woodlands, heathlands, grasslands, swamps, marshes, and vernal ponds. Some 25 federally protected species occur in the park, most prominently the threatened piping plover. The seashore is a significant site for this species with roughly five percent of the entire Atlantic coast population nesting here. Cape Cod National Seashore also supports 32 species that are rare or endangered in Massachusetts. Some of these, such as the common tern, are conspicuous; far less noticeable is the elusive spadefoot toad which spends most its life buried in the sand, emerging only on warm nights with torrential rainfall.

The protection of both the natural and cultural history of the Cape is a constantly evolving practice. In recent years the park has had to deal with overcrowded sites, traffic congestion, vehicle damage to bird nesting areas, air and water pollution, groundwater extraction and contamination, beach erosion, historic structure deterioration, declining forest land, and the expansion of the Provincetown Airport.

There are some 600 private homes within the park, expansion rules for which were thought to have been settled when the park was created. Yet the zoning guidelines established for structures in the park were just that—guidelines. Each of the six towns in the area was expected to make those guidelines law by modifying zoning laws for land within park boundaries. When Supt. George Price Jr. arrived in 2005, it became clear that only Eastham’s zoning had stayed true to the seashore’s intent. In one Wellfleet case, a 550-square-foot cottage on a tiny spit of land at the south end of Griffin Island was knocked down in 1984 to build an 1,812-square-foot home. This property was later knocked down and building has begun on a 5,848-square foot mansion, a 203-percent increase over the 1984 home, and 963-percent over the original cottage. Wellfleet zoning, since changed, was helpless to control this. Superintendent Price has said, “My number one concern is this issue of large houses . . . a sudden assault, if you will.”

Looking at the first 50 years of Cape Cod National Seashore, I realize that the Cape is not only Thoreau’s “bare and bended arm” battling the forces of the Atlantic and development. It is a hook, a seine, a curved lobster trap, a billowing net that captures everyone who wanders by. Tales are legion of children who spent summers at the Cape and were drawn back year after year, bringing with them their children and grandchildren. The old families are still there, in cedar-shingled homes, and the Kennedys, who have cherished their Hyannis homes for generations, continue to find solace here.

Sen. Ted Kennedy (with Congressman Bill Delahunt) stepped up in 2006 when the North of Highlands Campground in Truro was to be put on the market for possible development. They acquired the first $2 million in funding to preserve the campground—57 acres within the bounds of the national seashore. I suggested we ask Senator Kennedy to consider writing the preface to this 50th anniversary book. On August 25, 2009, I received word that not only would the senator be happy to do so, but that he had graciously offered to write the full introduction. At about 2:00 in the morning, I happened to have the BBC news on the radio when I heard that Ted Kennedy had passed away at his home on the shore of Cape Cod in Hyannis.

Many great writers have written exquisitely of Cape Cod. One unheralded local writer captured its essence with clarity and passion. More than 50 years ago, when the fate of Cape Cod National Seashore was still uncertain, columnist Jerry Burke wrote in the Yarmouth Register, “In our shrinking, defiled, and exploited continent we must hold on to the few remaining miles of unspoiled beaches . . . We must not diminish the Great Outer Beach by the length of one gull’s wing or the shadow of one beach plum. Let America come here and replenish its soul.”

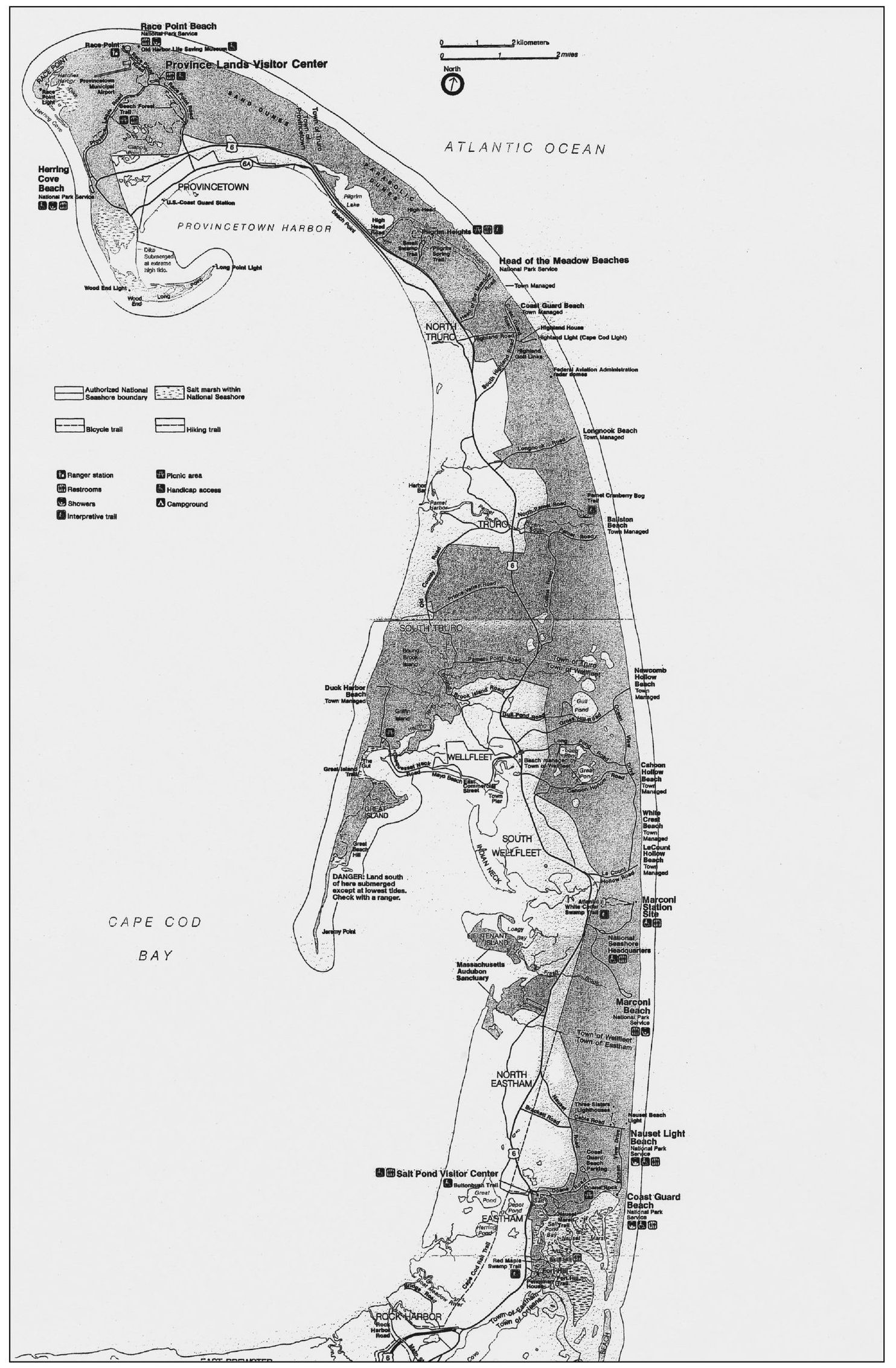

The shaded parts of this map show how much of Outer Cape Cod is protected within Cape Cod National Seashore. Included are about 40 miles of Atlantic Ocean beach, and both ocean and bay sides of Wellfleet and Provincetown.