I commented to an Egyptologist at the Temple of Luxor how remarkable it was to see four fellahin with only ropes skillfully maneuvering a ten-ton stone block. “Oh,” he replied, “they have been doing that kind of teamwork for the past five thousand years!” (Bass, 1995). The team or small group may be permanent or temporary. Contact is usually face-to-face but increasingly may take place through e-mail and conference television. Regardless of whether they arise spontaneously or are elected or appointed, the members who emerge as leaders perform two essential functions: (1) they deal with the groups and the member’s performance, and (2) they provide socio-emotional support to the group members (Bales, 1958a; Bales & Slater, 1955).

Any or all members can emerge as leaders, depending on how much of the functional roles they enact—the particular patterns of behavior they display in relation to the performance of the group or its socioemotional development. Leaders enact these task-relevant and socioemotional group-building and maintenance roles. Nonleaders are more likely to enact individual roles. These are less functional for the group’s development and maintenance. As formulated by Benne and Sheats (1948), task roles include those of initiator of the activity, information seeker, information giver, opinion giver, elaborator, coordinator, summarizer, feasibility tester, evaluator, and diagnostician. Group-building and maintenance roles include patterns of behavior such as encouraging, gate-keeping (limiting monopolistic talkers, returning the group to the agenda, and keeping the group on course), standard setting, expressing group feelings, consensus taking (sending up “trial balloons”), harmonizing, reducing tension (joking, “pouring oil on troubled waters”), and following. (This last role is consistent with what was said in earlier chapters about the positive correlation of leadership and followership.) Nonfunctional individual, self-concerned roles involve patterns of behavior such as aggression, blocking, self-confessing, competing, seeking sympathy, special pleading, disrupting, seeking recognition, and withdrawing.

Roby (1961) developed a mathematical model of leadership functions based on response units and information load. According to Roby, the functions of leadership are to: (1) bring about a congruence of goals among members; (2) balance the group’s resources and capabilities with environmental demands; (3) provide a group structure that is necessary to focus information effectively on solving the problem; (4) make certain that needed information is available at a decision center when required. Consistent with this view, Stogdill (1959) suggested that it is the function of the leader to maintain the group’s structure and goal direction and to reconcile conflicting demands that arise within and outside the group. For Stogdill, the functions of leadership also included defining objectives, providing means for attaining goals, facilitating action and interaction in the group, maintaining the group’s cohesiveness and the members’ satisfaction, and facilitating the group’s performance of the task. According to Schutz (1961b), the leader has the functions of: (1) establishing and recognizing a hierarchy of group goals and values; (2) recognizing and integrating the various cognitive styles that exist in the group; (3) maximizing the use of group members’ abilities; (4) helping members resolve problems involved in adapting to external realities, as well as those involving interpersonal needs. Bowers and Seashore (1967) maintained that the functions of leadership are the support of members, the facilitation of interaction, the emphasis on goals, and the facilitation of work. For Cattell (1957), the leader maintains the group, upholds role and status satisfactions, maintains task satisfaction, keeps ethical (norm) satisfaction, selects and clarifies goals, and finds and clarifies the means of attaining goals. For Hollander (1978), goal setting was a particularly important function of the leader. And P. J. Burke (1966a, 1966b) showed that antagonism, tension, and absenteeism occurred when the leader failed in this function. According to Hollander, the leader also provides direction and defines reality, two more functions that are necessary for the group’s effectiveness. If successful, such direction by the leader is a valued resource. As a definer of reality, the leader communicates relevant information about progress and provides needed redirection to followers.

Earlier chapters explored the interacting nature of leader-follower relations. This chapter concentrates on the effects of the followers as a group or team on its leadership and the effects of the leadership on the group or team. It concludes with sharing of leadership of the team. What the leadership does depends on the nature of the team. In the same way, the team depends on the nature of the leadership. Its leadership often makes the difference in the success or failure of the team’s efforts (Katzenbach, 1997). In the last century, there were several revolutionary changes in how work and service were to be done. The job of an individual became less a single bundle of tasks and more a varying set of tasks in coordination with other members of a team. Increasingly, work is done in teams. Even when individuals still have much work to do by themselves, they must still join parallel teams to complete it or for other reasons, such as to contribute to quality improvement, committees, and task forces. A single person may be a member of many parallel teams while still responsible for individual assignments (Campion, Pappar, & Medsker, 1996). Lawler and Cohen (1992) estimated that 85% of Fortune 100 firms used parallel teams.

A group is a collection of people with common boundaries, sometimes with broad objectives. A team is a group that is focused on a task with a narrow set of objectives (Hackman & Johnson, 1993). A group may have a task, such as to follow directions or to find answers to problems. But a group is less likely to be focused like a team primarily on specific tasks. Before 1990 many studies of groups were actually studies of teams. Both groups and teams exhibited mutual and reciprocal influence among members. But usually there is a stronger sense of identification by members of a team than a group. Team members share common goals and tasks; group members may belong to the group for personal reasons that are in conflict with the group’s objectives. Task members usually work interdependently; group members may work independently. Team members have more specialized and differentiated roles, although they are likely to play a single primary role; group members more often play a variety of roles (Hughes, Ginnett, & Curphy, 1993). Team-work more often requires monitoring performance of self and other members, self-correcting errors, providing task and motivation reinforcement, adapting to unpredictable occurrences, closing communication loops, and predicting other team members’ behavior. Mental models need to be shared (Salas, 1993). Much of the leadership in teams may be provided by the members themselves.

In the third edition of Handbook of Leadership, this chapter focused on leadership of small groups. In the fourth edition, the chapter reflects the rapid growth in interest from the 1980s onward in organizing teams, team-work, and team leadership and the declining research interest in leading informal, transient small groups (Ilgen, 1999). However, much of what was learned about small groups remains relevant to teams and team leadership. Research about work and leadership in groups is now more likely to be called work in teams. Among other things, to be an effective team, members in their interdependence must pursue shared and valued objectives. They must pay more attention to processes and their shared roles and responsibilities must be more clearly defined (Dyer, 1984).

The use of teams by utilitarian organizations has increased since the 1990s (Lawler, 1998). Authority has been decentralized. Traditional chains of command have been replaced by empowered teams (Ray & Bronstein, 1995). We are in the midst of a changeover from dividing the tasks of labor into their simplest components, as advocated by theorists ranging from Adam Smith (1776) to Frederick Taylor (1912). Work has been reengineered from production in assembly lines to teamwork in policy-making decisions, therapeutic efforts, family assistance, and education (McGrath, 1997). The reason is that teams ordinarily achieve more than pooling the individual efforts of the members working alone (Bass, 1965). “The growing interdependence of human functioning is placing a premium on the exercise of collective agency through shared beliefs in the power to produce effects by collective action” (Bandura, 2000, p. 75).

Early Interest in Group Effort. There were early instances of the changeover in interest from individual to group effort. De Toqueville (1832/1966) commented on how American settlers formed voluntary, temporary teams to get work done. LeBon (1897) explained what happens when people are in groups rather than alone. People in groups were found by H. Clark (1916) more suggestible than when isolated. Bechterew and Lange (1924) completed numerous experiments on the influence of the group, a topic of considerable political interest in a Soviet society aiming to develop collectivism in the workplace. Elton Mayo’s familiar Hawthorne studies begun in 1924 to show the importance of good lighting in the workplace, publicized the importance of interpersonal relations between supervisor and workers (Roethlisberger & Dixon, 1947). Burtt (1929) made explicit the case for working in groups rather than alone: “We are essentially social animals and most of us find it more agreeable to do things in company than to do them alone” (p. 193). Moreno (1934/1953) introduced sociometry to show the influence on group performance of choice of partners. Lewin’s (1939) theory of group dynamics was seminal in demonstrating the value of participation and team goals.

Trist and Bamforth (1951) described the teamwork in long-wall coal mining. Bamforth had been a miner and came from a village of coal miners. He won a scholar-ship to work with Trist. Assigned by Trist, he returned to the same mine in which he had originally worked to find that its individually assigned jobs had been replaced by working in teams. Productivity and satisfaction had increased. Bamforth told Trist that work in the mine had returned to the way the miners’ fathers had worked before “rationalization” had introduced inflexible individual assignments (Fox, 1990)! Our earlier chapters noted developments from the mid–twentieth century onward, exemplified by military leadership research ranging from army squads to air force aircrews, and Coch and French’s (1948) study of the effects of goal setting and participative practices. By the 1960s, Nonlinear Systems, a small California electronics firm, had eliminated its assembly line in favor of an organization of teams, and Volvo’s automobile engine assembly was changed from assembly lines to teamwork (Bass, 1965). Teamwork was encouraged by System 4 of Likert’s concept (1961a) of organized overlapping groups from one echelon to the next in decision-making hierarchies. Each leader of a group participated in a decision-making group of his peers at the next higher organizational level (see Chapter 17).

Prevalence. Teams have been employed in Japan since the days of the Samurai. Small-group research in the mid–twentieth century attested to the greater effectiveness of team over individual work. Lawler, Lawler, Mohrman, and Ledford (1995) estimated that as many as 85% of large Western firms were using some form of teams, many self-managed. Team decision making is more effective than the decisions of its individual members. Among 222 project teams solving problems, the decision based on the group process was better that that of the team’s most proficient member in 97% of the cases. Only 40% of the superior decisions could be explained by the average member’s decision (Michaelson, Watson, & Black, 1989).

Teams permit each member to take on larger tasks. With cross-training and reengineering of tasks, members can substitute for one another. They are better motivated when given wider latitude than operating on a traditional assembly line. The greater productivity in the United States with fewer employees is usually attributed in the popular press to technological advances, but some of it may be due to the switch from assembly lines to team-work. The attitudes and activities of the group transcend those of its individual members. Group and team norms can survive even if all the members are changed. Members behave differently when they are isolated from one another than when they are all together. The leader’s dyadic relations with each of his or her subordinates may not reflect the leader’s relations with the same subordinates as a team. The team’s relationship to the leader may be more important than the individual employee’s relationship to the leader (Bramel & Friend, 1987). The team approach has had to be extensively modified from its application in collectivistic Japan to individualistic North America. In Japan, harmony is of singular importance. In the United States, dissent has to be endorsed and valued, allowing for productive controversy and constructive thinking. Team structure has to be fluid, incorporating core members with part-timers. Teams have to be encouraged and enabled to make decisions for themselves (Nahavandi & Aranda, 1994).

The team’s drive, cohesion, collective efficacy, potency, selection, alignment, and attainment of goals are likely to be influenced by its leadership. Its leadership is likely to be influenced by the team’s drive, cohesion, collective efficacy, selection, and attainment of objectives. The overall evidence points to greater accomplishment in teams with greater collective drive, cohesion, efficacy, and potency. For example, a group’s beliefs in its collective efficacy have been shown in banking to make an important contribution to continuing effort and performance accomplishment (Lewis & Gibson, 1998). Comparable results have appeared in both experimental teams and natural groups in business, athletics, military combat, and urban neighborhoods (Bandura, 2000). A meta-analysis by Gully, Beaubien, Incalcaterra, et al. (1998) found a strong relationship between collective capability and team performance. These results go beyond the performance of the individual members and generalize across tasks and cultures (Gibson, 1999).

Deindividuation. The group effect becomes especially strong if deindividuation occurs, that is, if the group members lose their identity as individuals and merge themselves into the group. In such a case, the members lose many of their inhibitions and behave uncharacteristically (LeBon, 1897). The disinhibition of deindividuation makes it easier for team members to discuss intimate problems with a stranger whom they expect never to see again than with friends or relatives. Festinger, Pepitone, and Newcomb (1952) studied groups of students who were required to discuss personal family matters. They confirmed that the students experienced less restraint in doing so under a condition of deindividuation. They minimized the attention they paid to one another as individuals. When it was present, deindividuation was a satisfying state of group affairs associated with increased group attractiveness. In the same way, Rosenbaum (1959) and Leipold (1963) found that participants preferred to maintain a greater psychosocial distance between themselves and their partners when potentially unfavorable evaluations might be fed back to them than when no such information was anticipated. The disinhibition of deindividuation may help explain how members of special operations teams can take on extremely dangerous, life-threatening missions.

Individual identity is ordinarily stressed if rewards are anticipated; deindividuation is more likely to occur if punishment is expected. Furthermore, deindividuation increases with anonymity, the level of emotional arousal, and the novelty of the situation. The loss of inhibition is reflected in less compliance with outside authority and more conforming to the demands of the group or team. Responses are more immediate, and there is less self-awareness and premeditation. The collective mission is stressed over the individual’s needs. Disinhibition and the loss of self-identity unleash the energy to accomplish great feats if they have constructive direction. They also facilitate the rabble-rouser. We become disinhibited from ordinary social constraints when we lose ourselves in a crowd. A riot-inciting leader can generate mindless mob violence.

Emotional contagion occurs even in a two-person conversation. People automatically mimic and synchronize their own movements with the facial expressions, postures, vocal utterances, and behaviors of other people. Subjective feelings are induced in the same way (Hat-field, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1993).

Overt and Covert Effects. Particularly in collectivist societies such as China, Japan, and Korea, the group is likely to have a strong influence on its leader. Thus, Furukawa (1981) showed, in a survey of 1,576 Japanese managers, that managers establish their primary management objective from among a set of possibilities after judging how well it fits with their work team’s interests and favorability to them.

Leader-member relations are also affected less overtly by the team or group. Some of the assumptions that determine an organizational culture are fantasies that are shared by members of a group that is embedded in the larger organization (Kets de Vries & Miller, 1984a). Ide-alization or devaluation of the leader and dependence on him or her is one such shared fantasy. One group, as a group, in the same larger organization will be dependent on whoever is assigned the job of group leader. Another group, without the same assumptions, will displays more independence or counterdependence, regardless of who is appointed leader. A leader of a group with a clique who behaves the same way as the leader of another team without a clique will be evaluated differently by the two groups. E. R. Carlson (1960) showed that groups that contain cliques are less satisfied with their leaders than are groups that are free from such cliques.

Team-Member Exchange Effects. Team effects appear to augment the leader’s impact on the satisfaction of individual members. Thus Seers (undated) extended Graen’s (1976) concept of the quality of the dyadic leader-member exchange to the quality of the team-member exchange. Items that correlated most highly with the factor of the quality of the team-member exchange among 178 hourly employees who worked in one of 19 teams included “how often I volunteer extra help to the team” and “how often others on the team help me to learn better work methods.” Eighteen percent of a team member’s work satisfaction was accounted for by the favorable quality of the member’s exchange relationship with the team leader. An additional 4% was due to the quality of the exchange relationship with the team. The comparable figures for a member’s satisfaction with coworkers were 11% owing to the quality of the leader-member exchange and 27% owing to the quality of the team-member exchange.

Characteristics of the Group’s Members. The means and variances in the attributes of individual members make a difference to the leadership of the group and its patterns of influence. Thus, Dyson, Godwin, and Hazelwood (1976) were able to link members’ consensus to the influence of decisions in homogeneous but not in heterogeneous groups. D. G. Bowers (1969) found that the leaders’ importance is greater for teams composed of particular kinds of employees. Among 1,700 work groups from 22 organizations, Bowers observed that groups made up of longer-service, older, and less educated members attached greater importance to the supervisor and his or her direct influence on their behavior. The effects were especially relevant in administrative, staff, production, and marketing groups. In better-educated, shorter-service, younger groups, especially those whose members were primarily female, such as clerical and service groups, less importance was given to the role of the supervisor and greater importance was given to the behavior of peer members of the group.

Caveat. The return for effort needs to be an equitable exchange for the team members (Naylor, Pritchard, & Ilgen, 1980) and must also meet social and transformational objectives (Sivasubrahmaniam, Murray, & Avolio, 2002). Group efforts are superior to the average individual operating alone. However, there are notable exceptions. A survey of 15% of 4,500 teams in 500 organizations mentioned inadequate conflict management and group problem solving as barriers to team effectiveness. And 80% noted as shortcomings of team organization instances where rewards, appraisals, and compensation were based on individual, not team performance. Also, group effectiveness was limited by individuals’ competitiveness (Koze & Masciale, 1993). Carless, Mann, and Wearing (1995) reported that team cohesion was even more highly correlated with team performance than transformational leadership. But Erwin (1995) failed to find that team cohesion predicted team performance.

Leadership and Team Performance. The team narrows the range of possible leader–individual subordinate interactions in the interests of equity and time and because of the team’s expectations about its leadership. The leadership is evaluated on the basis of the team’s quantity and quality of productivity, service, and costs, the team’s ability to work together, the team members’ satisfaction and development (Hackman, 1990), and the performance of the teams rather than on the performance of their individual members (Schriesheim, Mowday, & Stogdill, 1979). The leader’s contribution to the team’s productivity is likely to be reduced by faulty group interaction processes (Steiner, 1972) or enhanced by “assembly bonus effects” (Collins & Guetzkow, 1964), which occur mainly with difficult tasks (Shaw & Ashton, 1976). That is, above and beyond individual members’ capabilities to deal with the task they face, faulty leader-team interactions may result in performance that is worse than if the members had been free to work alone and to remain uninfluenced by the leader. Nonetheless, when members work in a well-led team, their performance is likely to be better than what might have been expected from a simple pooling of their individual capabilities as members (Bass, 1980).

By the late 1940s, Hemphill (1949b) and Hemphill and Westie (1950) had published reliable and valid measures of group dimensions, such as status differentiation, group potency, and cohesion. Fleishman and his colleagues completed a program of investigations about team performance involving refined measures of human abilities, tasks, and contexts (Fleishman & Quaintance, 1984). Seven dimensions of team performance and refined ways to measure them were developed: (1) orientation, assignments, and exchange of information; (2) distribution of resources to match tasks; (3) timing and pacing; (4) response coordination; (5) development and acceptance of team performance norms, reinforcements, conflict resolution, and balanced competition and cooperation; (6) monitoring system and individual adjustment to errors; (7) monitoring individual and team level procedures and adjusting to nonstandard activities (Fleishman & Zaccaro, 1992). Two among the many team survey inventories that have been created since then are the Bass and Avolio (1993) Team Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (TMLQ), and the Elliott (1997) Linking Skills Index (LSI). The TMLQ deals with the shared transactional and transformational leadership behavior within the team as a whole. Team variables such as collective efficacy, team trust, team potency, and team cohesiveness have been added. The LSI measures 11 dimensions, including the extent to which the team displays quality standards, setting objectives, participative decision making, delegation, active listening, and satisfactory work allocation. At a more microanalytical level Coovert, Campbell, Cannon-Bowers, et al. (1995) applied graph theoretical petrinets (Reisig, 1992) to quantitative analysis of effective and ineffective laboratory team coordination. Petri-nets made it possible to describe moment-to-moment interactions among team members and to distinguish between effective and ineffective processes, strategies, and behaviors (Salas, Dickenson, Converse, et al., 1992).

Stages in the Development of Groups into Teams. The consistency and importance of the phases in a group’s development were noted and observed by many investigators. Leaders have to learn to respect these phases. Thus, Terborg, Caetore, and DeNinno (1975) demonstrated that groups must work together for some time before they can begin to behave as a team. The early period is crucial. Eriksen (2003) compared high-and low-performing teams. The high-performing teams, early on, started off well and progressed well until completion of their projects. The low-performing teams faltered in getting started and never fully recovered.

In one of the early studies of group development, Bales (1950) observed that small groups consistently exhibit phases in their problem-solving behavior. Bales and Strodtbeck (1951)1 demonstrated that after an introductory polite stage, the second phase in the development of small groups tends to involve a great deal of tension because of the members’ competition for leadership and the stabilization of the status structure. Thus, Heinicke and Bales (1953) observed that emergent leaders tended to be rated high in initiating suggestions and opinions in the first session and at the beginning of the second session, but during the second session, they began to engage in an active struggle for status. After consolidating their position in the second session, they became less active in the third and fourth sessions, permitting other members to play more active roles. But the leaders’ opinions and suggestions were still accepted. The leaders did not have to make as much effort to win their points.

In a detailed study of the first two stages of unstructured small experimental teams, Geier (1967) instructed some participants in a team task. Members entered their teams without an assigned role. The leader was the member whom the members perceived by consensus as having made the most successful attempt to influence the team. Stage 1 involved the rapid and painless elimination of contenders with negative characteristics. The second stage involved an intense struggle for leadership and the further elimination of competitors. Only 2 of 80 members in the various teams studied made no effort to gain leadership. Those who were uninformed, unparticipative, and rigid and hindered the attainment of goals were eliminated first. Attempts to recruit lieutenants and to gain the members’ support were most obvious in Stage 2. The roles of lieutenant developed in 11 of 16 teams. Of the 11 lieutenants, 7 had been contenders for leadership in Stage 1.

Tuckman (1965) reviewed some 60 studies involving experimental, training, and therapeutic groups. An analysis of these studies suggested two additional stages of development through which the groups had to go to reach full group maturity. The first two stages of forming and storming were like stages of politeness followed by conflict. Forming was characterized by testing and orientation; storming was characterized by intragroup conflict, status differentiation, and emotional response. The third stage was norming, characterized by the development of group cohesion, norms, and intermember exchange; and the fourth stage was performing as a team, marked by functional role interrelations and the effective performance of tasks. These stages of forming, storming, norming, and performing could overlap in some groups and alternate in others (Heinen & Jacobsen, 1976). The emergence and success of the different kinds of leadership that were needed could clearly be connected to each of these phases. For example, Erwin (1995) suggested that during the stages of norming and storming, compared to any external leadership, the internal team leadership was more important to the team’s effective development. Nevertheless, Pearce and Rode (2001) showed that for 71 teams in a program of change, the amount of enablement by higher-level management (providing needed resources, training, and support) correlated from −.28 to −.35 with the teams’ prosocial behavior, commitment, effectiveness, and absence of social loafing.

Re-forming. The development of teams continues into further stages (Gersick, 1985). About halfway through the life cycle of problem solving as groups and teams (which presumably have reached the fourth, performing, stage), the teams reform themselves. During this re-formation, groups reevaluate their progress to date, reach agreement on final goals, revise their plans for completing their assigned task, and refocus their effort toward completing the task. Following this re-formation, they concentrate more of their efforts on the critical aspects of performing the task and focus on accomplishing their task to meet the stated requirements. Near the completion of the task, efforts are made to shape the team product so it will fit environmental demands. Work is finalized, consistent with the requirements of the situation.

Structure and Purpose. Avolio and Bass (1994) conceived the stages in group development as going from unstructured groups to highly structured teams based on sharing of purposes, commitments, trust, drive, and expectations. In unstructured groups, there is no clear agenda or assignments; members are confused or conflicted about responsibilities and perspectives. Direction may be irrelevant to the group’s reason for existence. In highly structured teams, there is close monitoring by the members of one another for any deviations, which are then addressed. Rules are strictly enforced. Members are unwilling to take risks.

A team begins as a group without a necessarily shared purpose, commitment, trust, or drive. It becomes structured into a team and becomes fully developed when it reaches a high degree of shared purpose, commitment, trust, and drive (Avolio & Bass, 1994). The mental stage of the team as a team is important to the emergence of leaders and the effects of leadership. For example, different leaders emerged in successive stages of therapy in a psychiatric ward (S. Parker, 1958). Likewise, Sterling and Rosenthal (1950) reported that leaders and followers changed with different phases of the group process; the same leaders recur when the same phases return. Kinder and Kolmarm (1976) found that in 23-hour marathon groups (night-and-day-long sensitivity training groups), gains in self-actualization were greatest when initially highly structured leadership roles were maintained early in the groups’ development and switched to low-structured leadership roles later in the groups’ development. Okanes and Stinson (1974) concluded that more Machiavellian persons were chosen as informal leaders early in the development when groups could still improvise; once the groups became more highly structured teams, however, Machiavellian persons were less likely to be chosen as leaders. Vecchio (1987) concluded that the one aspect of the Hersey-Blanchard model (1977) that had validity was the utility of using directive leadership early in the group’s development and then employing more participative leadership for the group as it matured.

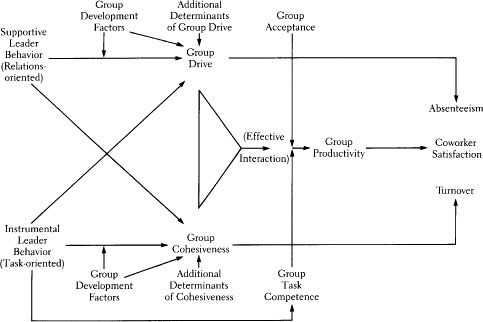

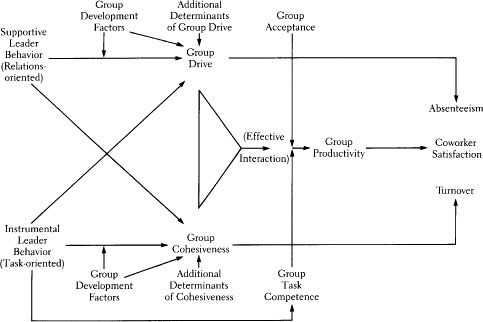

Figure 26.1 Model Linking Leadership to Group Outcomes

SOURCE: Adapted from Schriesheim, Moday, and Stogdill (1979). (Modifications are shown in parentheses. Effects of leadership on group outcomes are not shown.)

On the basis of a review of the literature, Stogdill (1959, 1972) identified three possible main effects of the leader on organized groups: productivity, drive, and cohesiveness. The rational model (Figure 26.1) created by Schriesheim, Mowday, and Stogdill (1979) proposed that a group’s drive and cohesiveness interact with each other to generate a group’s productivity. In the model, supportive or relations-oriented leadership behavior interacts with instrumental or task-oriented leadership behavior to promote a group’s drive and cohesiveness. All this occurs in the context of the group’s development, which also contributes to the group’s drive and cohesiveness and results in more effective interaction among its members. Then, if the group as a team has the competence to complete the task and accepts the responsibility for doing so, its productivity increases; the satisfaction of members with one another is greater; and the members’ tendency to be frequently absent or to quit is reduced. According to a meta-analysis by Salas, Mullen, Rozell, et al. (1997), role clarification and structuring relationships were keys to successfully developing teams and their performance.

Leaders Make a Difference in Team Structure. Leaders differ in how much they affect the extent to which the intended structure of relations within a team and its input and outputs is actually the enacted structure. In a study of 39 work groups in three organizations, Inderrieden (1984) found that, along with the uncertainty of the task, the leaders’ need for power and self-actualization were the strongest predictors of the actual structure of the work groups.

Effective leadership allows groups to move systematically through the necessary developmental stages. Groups that are unable to develop a differentiated leader-follower role structure will be unable to engage in the effective performance of tasks (Borgatta & Bales, 1953b). Conversely, groups with a high degree of consensus about their leadership will be more effective and better satisfied than will those that do not reach such a consensus. De Souza and Klein (1995) conducted an experiment using 468 college students in initially leaderless quartets of four with tasks and goals. Groups with emergent leaders outperformed groups without such leadership. The emergent leaders had greater ability for the task and commitment to the group goal. The clarity of leadership in 170 health care teams was related to clear team objectives, high levels of participation, commitment to excellence, and support for innovation (West, Borrill, Dawson, et al. (2003).

Stages and Outcomes. Avolio, Jung, Murray, et al. (1996) studied the shared team leadership of 188 undergraduates in teams of five to seven members early and late in the semester. They used the Team MLQ. The expected correlations with outcomes in extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction declined from the early phase to the late phase, but inspirational motivation increased in correlation with collective efficacy from .33 to .63 and with potency from .49 to .66. For contingent reward, increases were recorded from .11 to .63 with collective efficacy and .18 to .63 with potency. Passive and active management by exception showed little change.

Stogdill (1972) suggested that the cohesiveness, drive, and productivity of a team are closely related to its developmental stage and what is required of the team leader. The team’s drive appears in every stage, but the arousal and tensions of the second stage of storming most closely reflect the amount of that drive. The specific tasks that the team is motivated to perform, however, may differ across the stages. Thus, for instance, in the second stage, the team’s drive is directed toward evolving a structure for the team. In the third stage, it operates to develop greater cohesiveness. In the third stage (norming), roles have finally been accepted and communication has improved; team cohesiveness emerges. In the fourth and final stage, effective performance of the task, team productivity is seen.

The functions of the leader depend on the stage of a group’s development. For instance, relations-oriented leadership behavior will contribute to the team’s need to develop cohesiveness in the third stage (norming), and task-oriented leadership behavior will facilitate the team’s accomplishment of the task in the fourth stage (performing).

Stages and Role Boundaries. The team’s development can be seen in the stabilization of the role boundaries of the individual members, including those of the leader. The role boundary set of any member encompasses the acts that the other group members will accept. Boundaries are established by fairly stable role expectations that are often conveyed by the leader. In group experiments by Gibb (1961), one leader with a permissive leadership style was followed by another with a restrictive style, and vice versa. In other groups, one leader was followed by another with the same style. Group members accepted and responded more readily to leaders who followed other leaders with the same style of either latitude or restriction in the members’ prescribed range of behaviors. The members were also less defensive and more productive in problem solving. Expectations were built quickly, with minimum cues, and survived over long periods. Esteemed and influential members—those frequently nominated as such in sociometric tests—tended to stay within the realistic boundaries prescribed by the group. Individuals who were less frequently chosen were those more likely to violate the boundary specifications. (Perhaps those who were chosen more often had a wider range of behaviors and more role space in which to move.) The members responded to an individual member’s role actions outside the role’s boundaries by pretending not to see or hear the behavior, ignoring it, engaging subtle fighting or open rebellion, isolating the member, or forcing his or her withdrawal.

Given the power of norms, groups tended to select goals and perform activities that were commensurate with the norms. To exert influence, the behavior and goals of the leader had to be consonant with the group’s goals. But high levels of defensiveness in the group prevented the effective exercise of such influence. The leadership also needs to take into account whether members conform to avoid criticism, to serve their own interests, to fulfill obligations, or to fit with the member’s values and principles.

Groups undergo an orderly reduction in defensiveness as they mature, according to J. R. Gibb (1964). While a group is forming, its members remain superficial and polite to each other and trust is low. After members have learned to trust one another (presumably after some storming), they learn how to make effective decisions and gain greater control over the choice of goals in the norming phase. With these better goals, they can make better use of the group’s resources.

A stable structure of relations must be developed for a group or team to become cohesive (Heinen & Jacobsen, 1976; Sherwood & Walker, 1960; Tuckman, 1965). A leader has important effects on a group’s development of a stable structure (Heslin & Dunphy, 1964). Recognizing this fact, Bion (1961) found that if the discussion leader of a therapy group failed to provide structure, the members, striving to arrive at a structure, sought a leader among themselves. As was discussed in previous chapters, during the early stages of a group’s development, members may want and accept more direction. At this time, leaders may exert a greater influence on the stabilization of a group’s role structures and thus have a greater impact on the group’s cohesiveness.

In a study of Japanese nursery school children, Toki (1935) observed that early separation of an emergent leader from the group resulted in a disintegration of the structure of the group. The structure was more likely to hold up when the emergent leader left late in the group’s development. When an adult leader was introduced, the structure built around the child leader collapsed.

Differences among groups that are likely to affect what the leader can and will do include the group’s drive, cohesiveness, size, compatibility, norms, and status. Earlier chapters looked at some of these effects from a variety of different perspectives.

Grant, Graham, and Hebeling (2001) noted from 32 case study reports about team projects that when the team members dedicated all of their time to the project and the project was of singular importance to the leader, the leader had to dedicate a great deal of time to the careful selection of skilled, compatible, and collaborative members. Bass, Flint, and Pryer (1957b) demonstrated that the motivation of all the members of a team affected the success of the leader. When all members are initially equal in status, an individual is more likely to become influential as a team leader if he or she attempts more leadership than others do. However, among highly motivated members, such attempted leadership was found to exert little effect on who emerged as a leader to influence the team’s decision. In the same way, Hemphill, Pepinsky, Shevitz, et al. (1954) showed that team members attempted to lead more frequently when the rewards for solving a problem were relatively high and they had a reasonable expectation that efforts to lead would contribute to the accomplishment of the task. Durand and Nord (1976) observed subordinates in a textile and plastics firm who felt that their success or failure was in the hands of forces outside their control. (Presumably they were lower in team motivation. They tended to see their supervisors as initiating more structure and showing less consideration.)

A team’s drive is likely to be high when members are highly committed. Members are more likely to want to expend energy for such teams. Gustafson (1968) manipulated members’ commitment to their student discussion teams by varying the extent to which grades for a course depended on the team’s performance. Less role differentiation into leaders, task specialists, and social-emotional specialists was perceived by members with either a strong commitment or a weak commitment; that is, the three functions were not differentiated, but the teams showed less social-emotional behavior when their members were highly committed. In an analysis of 1,200 to 1,400 subordinates’ descriptions of their teams, Farrow, Valenzi, and Bass (1980) found that directive leadership and delegative leadership were seen more frequently when the subordinates’ commitment to the teams was high.

Group cohesiveness has been defined in many different ways. It has been defined as the average member’s attraction to the group (Bass, 1960) and as all the forces acting on members to remain in the group (Festinger, 1950). It has been conceived of as the level of the group’s morale (C. E. Shaw, 1976), the individual needs satisfied from group membership (Cartwright, 1965), and the extent to which members reinforce one anothers’ expectations about the value of maintaining the identity of the group (Stogdill, 1972). It has been identified by highly correlated variables such as the members’ commitment to the group, the presence of peer pressure, the felt support from the group, and the absence of role conflict in the group. For some, it has meant valued group activities, group solidarity, willingness to be identified as a member of the group, and agreement about norms, structure, and roles.

Podsakoff, Todor, Grover, et al. (1984) collected data from 1,116 mainly male employees working in a variety of city and state government agencies. Cohesiveness significantly increased the employees’ satisfaction with supervisors who practiced a good deal of contingent rewarding. It significantly decreased satisfaction with supervisors who engaged in a lot of noncontingent punishment. Cohesion had no significant effect on satisfaction with supervisors who were contingent punishers or noncontingent rewarders. According to Dobbins and Zaccaro (1986), cohesiveness moderated the effects of leaders’ consideration and initiation of structure on subordinates’ satisfaction among 203 military cadets. Leaders’ consideration and initiation of structure was correlated more highly with subordinates’ satisfaction in cohesive compared to uncohesive groups.

Drive and Cohesiveness. The motivation of a group includes its drive along with its cohesiveness. The drive of a group refers to its level of directed energization; the cohesiveness of the group is the level of attachment of the members to the group and its purposes. Clearly, the two are related in that both increase with the extent to which the group and its activities are valued by the members. Nevertheless, many investigations have focused on one or the other. The drive and cohesiveness have been merged by focusing on the members’ loyalty, involvement, and commitment to the group (Furukawa, 1981). Stogdill (1972) conceived group drive to be the arousal, freedom, enthusiasm, or esprit of the group and the intensity with which members invest their expectations and energy on behalf of the group. Steiner (1972) defined group motivation similarly as the willingness of members to contribute their resources to the collective effort. Zander (1971) found such motivation to depend on the members’ desires to achieve success and avoid failure, as well as their previous history of success (Zander, 1968) and pressures for high performance (Zander, Mcdow, & Dustin, 1964).

Although drive and cohesiveness ordinarily are correlated, Stogdill (1972) concluded, from a review of 60 studies, that under certain circumstances, the level of group drive (or team drive) conditions the relationship between productivity and cohesiveness. Under routine operating conditions and low drive, team productivity and cohesiveness tend to be negatively related, while under high drive, they tend to be positively related. The seemingly paradoxical findings are readily explained when group drive is studied along with productivity and cohesiveness. When the team’s drive is high, members’ energies are directed toward its goal. If the team is also cohesive, the members will work collectively and productively toward that goal. On the other hand, if the group’s drive is low, the members’ energies will be directed elsewhere. If the team also remains cohesive, the members will reinforce one another’s tendencies to ignore the team’s productive goals and seek satisfaction from nonproductive activities.

Expectations, Solidarity, and Identification. Avolio and Bass (1994) observed that the expectations of unstructured, uncohesive groups were lower than those of more structured, cohesive teams and that expectations were exceeded in high-performance, highly cohesive teams. Borgatta, Cottrell, and Wilker (1959) studied groups that differed in the members’ expectations about the value of group activities. The higher the initial expectation, the higher the final level of satisfaction for groups as a whole. Leaders of low-expectation groups changed their assessments more than leaders of high-expectation groups did.

The ease of the flow of influence between the leader and followers was expected to be associated with cohesive social relations (Turk, Hartley, & Shaw, 1962). Theodorson (1957) found that the roles of task leader and social leader were combined in cohesive groups but were separated in poorly integrated groups. Weak group cohesiveness provided a condition under which those who scored high in sociability attempted to develop cooperation through increased interaction, while those who scored low in sociability tended to remain passive (Armilla, 1967).

Gergen and Taylor (1969) demonstrated that high-status participants, when presented to a group in a solidarity setting, tended to meet the group’s expectations but failed to meet expectations when they were presented in a productivity setting. Low-status participants in the productivity context presented themselves more positively; in the solidarity condition, they became more self-demeaning.

Acceptance of a group’s leaders is linked to identification with the in-group. Bulgarian or Yemenite immigrants to Israel identified themselves first as Jewish, then second as Bulgarians or Yemenites. As a consequence, they could more easily support and follow Israeli leaders. On the other hand, Israeli immigrants who identified themselves first as Germans, Americans, or Moroccans were more likely to accept the Israeli leaders only if their self-evaluation was not rooted in the old country (Eisenstadt, 1952).

Implications for Structuring. Arguing that norms, structure, and roles are clearer in cohesive groups, J. F. Schriesheim (1980) proposed that initiation of structure by the leader is redundant in cohesive groups. But more initiation by the leader is likely in groups in which cohesiveness is low, groups that have less of a normative influence on members, and groups in which the members are more likely to be dependent on the leader than on the group. An analysis of data from 43 work groups in a public utility supported Schriesheim’s proposition by showing that satisfaction with supervision, role clarity, and self-rated performance correlated much more highly with initiation of structure by the leader if the groups were low rather than high in cohesiveness. Schriesheim also expected that the leaders’ consideration would contribute to the subordinates’ role clarity only in groups whose cohesiveness was high. Again, her supposition was borne out. She found a correlation of .31 between the leaders’ consideration and the subordinates’ role clarity in highly cohesive groups but corresponding correlations of −.05 and −.04 in groups in which cohesiveness was medium or low. Schriesheim inferred from these results that highly cohesive groups provide members with clear roles and that clarity is reinforced by supportive, considerate leaders. Such groups have little need for additional initiation from their leaders. Leaders need to structure such groups less tightly (House & Dessler, 1974). Again, consultative leadership will yield more subordinates’ satisfaction if the leaders feel that members are highly committed to the group and its goals (Farrow, Valenzi, & Bass, 1980).

Effects of the Group’s Agreement about a Leader. The leadership process is affected by whether the immediate group is in agreement on who will lead it. Agreement among the members about who should lead was found to be correlated with greater group cohesiveness (Shelley, 1960a) and with more frequent attempts to lead (Banta & Nelson, 1964). Bales and Slater (1955) obtained results showing that three different roles of members tended to emerge in groups that did not reach a consensus on who should lead: an active role, a task specialist role, and a best-liked-person role. In groups that had attained such a consensus, less role differentiation occurred; the active and task specialist roles were performed by the same member. Harrell and Gustafson (1966) reported that in groups lacking consensus, an active task specialist role emerged along with a best-liked-member role. Role differentiation occurred less in both their high-and low-consensus groups than in Bales and Slater’s study. In addition, attractive groups and those with the most interesting tasks tended to exhibit the least role differentiation.

Harmony and Cooperativeness. Consultation by the group leader was more frequent in work groups that were described by their members as harmonious and free of conflict (Bass, Valenzi, Farrow, & Solomon, 1975). Groups with cooperative members, compared with groups with competitive members, were more likely to develop leaders, evaluate fellow members more favorably, show less hostility, and solve their problems as a group more rapidly (Raven & Eachus, 1963). This finding is consistent with the conventional wisdom that suggests that it usually benefits the organization to encourage competition among groups with independent tasks but that competition should be discouraged within the groups.

Compatible Members. Groups composed of compatible rather than incompatible members are better able to elect competent leaders. They are also better able to use the resources and abilities of their members, since they are more likely to elect leaders who allow the highly competent members enough freedom to express themselves and to influence the groups’ performance (W. C. Schutz, 1955). Lester (1965) found that the emergent leader among the highly task-oriented members of an American Mount Everest climbing expedition was able to be more relations-oriented.

Thelen et al. (1954) factor analyzed the self-and group descriptions made by members of a discussion group. Five clusters of members were identified. Cluster A, composed of members who rejected fighting and pairing, made significantly more leadership attempts than did any other cluster. It preferred structure and cohesiveness, which prevent undue domination and intimacy. Cluster B, with ego needs for intimate relationships, showed little interest in differences in status. Cluster C, which preferred to avoid power struggles or responsibility, rejected competition for leadership. Cluster AC, which rejected fighting, supported and looked to the leader to support their status needs. Cluster BC, which accepted fighting, supported the leader and attempted to mediate conflicts to maintain the group’s cohesion.

Increased size affects a group’s leadership. It brings with it reduced opportunities to lead, more responsibilities and demands on the leader, and a possible widening of the span of control.2 As the size of the group increases, the number of interactional relationships among members increases at an extremely rapid rate. Graicunas (1937) deduced that a leader with two subordinates can interact with them both singly and in combination. The contacts can be initiated by the leader or by the subordinates, so that six relationships are possible. With four subordinates, the number of possible relationships is 44. With six subordinates, the number of possible relationships is 222. Graicunas concluded that executives should not have more than four or five subordinates reporting to them directly; because of the time required for personal contacts. Nevertheless, surveys of industrial executives3 indicated that corporation presidents may have from 1 to 25 assistants reporting to them. The average in the several surveys ranged from five to nine immediate assistants. But the evidence accumulated over the years indicates that five to seven is an optimum size for most groups, with the task determining whether smaller or larger size is most efficient (Bass, 1981). Data collected between 1993 and 1995 for 74 software product teams were found by Carmel and Bird (1997) to have a median membership size of five. The researchers accounted for the effectiveness that results from keeping team size small. It makes possible close communication and participation of all members in decisions.

Opportunities to Lead. The size of the group affects the emergence of a leader. Bass and Norton (1951) reported that the opportunity of any single member to take on the functions of leadership in a group decreased as the number of members increased.4 In agreement, Hare (1962) reviewed several studies that suggested that as the size of the group increases, individual members have less opportunity to talk and to attempt to lead. Fewer members can initiate leadership acts. Again, Warner and Hilander’s (1964) study of 191 voluntary organizations in a community found that the involvement and participation of members decreased as the size of the organization increased. To the contrary, J. H. Healy (1956) found that for chief executives of corporations, subordinates’ involvement in policy making was greater as the number of immediate subordinates increased.

As the size of a group increases, more differences appear in the members’ tendency to be talkative and in their attempts to be influential (Bales & Slater, 1955). In groups that ranged from 2 to 12 members, Bass and Norton (1951) reported that such differences increased directly with the increase in the size of the groups, and reached the maximum in groups of six members. But contrary to most researchers, Kidd (1958) found no relation between the size of a group and increases in the differences among members’ influence in groups of two, four, or six members. Blankenship and Miles (1968) also noted that the size of the units they led was less important to the decision-making behavior of executives than was their organizational level.

Changes in Leadership Style and Effects. Hemphill (1950b) studied groups with leaders whom the group members considered to be superior. He found that as the size of the groups increased, the members made greater demands on the leaders. Larger groups made significantly stronger demands on the leaders’ strength, reliability, predictability, coordination, impartial enforcement of rules, and competence to do the job. At the same time, larger groups required less consideration from the leaders for individual members.

Pelz (1951) observed that small groups were better satisfied with leaders who took their part than with those who sided with the organization. Larger groups (10 or more members) were better satisfied with leaders who supported the organization. Medalia’s (1954) results indicated that as the size of the work unit increased, workers’ perception of their leaders as “human relations–minded” decreased. Goodstadt and Kipnis (1970) found that as the size of the groups increased, supervisors tended to spend less time with poor workers and to give fewer pay raises to good workers. In 100 randomly selected chapters of the League of Women Voters, J. Likert (1958) found that officers engaged in more activities as the chapters increased in size, but the chapter presidents exhibited less interest in individual members’ ideas. Consistent with all these findings, Schriesheim and Murphy (1976) found that the leaders’ initiation of structure was related to satisfaction of members in larger work groups and that the leaders’ consideration was related to the satisfaction of members in smaller groups. However, Greene and Schriesheim (1980) showed that instrumented leadership was actually most influential in affecting drive and cohesiveness in larger work groups, while supportive leadership was most influential in smaller work groups.

A meta-analysis by Wagner and Gooding (1987) of 7 to 19 studies of the effects of participative leadership on various outcomes found that the positive correlation of perceived participative leadership with perceived satisfaction of subordinates remained at .44 and .42, respectively, in small and large groups, but the correlation between participative leadership as perceived by members and their acceptance of decisions fell from .44 in small groups to .31 in large groups. When independent sources of leadership and outcome data that were free of single-source bias were correlated, the results again fell for the acceptance of decisions, from .27 to .20, and for satisfaction from .25 to .03. Thus overall, participatory leadership practices generally had more salutary effects in smaller than in larger groups.

Kipnis, Schmidt, and Wilkinson (1980) reported that when trying to be influential, supervisors of large groups were likely to choose impersonal tactics such as assertiveness and appeals to a higher authority instead of more personal influence tactics such as ingratiation and bargaining. In small groups, relatively more personal and fewer impersonal tactics were employed by the same supervisors. This finding may explain why a small span of control does not produce close supervision (Bell, 1967; Udell, 1967).

Changes in Requirements. Thomas and Fink (1963) reviewed several studies that concluded that as groups enlarged, the leaders had to deal with more role differentiation, more role specialization, and more cliques. Slater (1958) noted that the stabilization of a group’s role structure became increasingly difficult with increasing size of the group.

Hare (1952) studied boys in groups ranging from 5 to 12 members. Leaders were found to exert more influence on decisions in the smaller groups, but the leaders’ level of skill was not related to influence. The larger groups demanded more skill from their leaders. In large groups, the leaders’ skill was positively correlated with the increased movement of members toward group consensus. Yet, in a comprehensive summary of personal factors found to be associated with leadership in natural and experimental groups, R. D. Mann (1959) noted that in groups of seven or smaller, intelligence seemed a little more important to leadership than adjustment; but in larger groups, adjustment increased slightly and intelligence decreased slightly in correlation with leadership.

Antecedents. Guion (1953) and G. D. Bell (1967) found that first-level supervisors tended to supervise fewer subordinates as the complexity of the job increased. The number of subordinates of chief executives tended to increase with the growth of the size of firms, according to J. H. Healy (1956). His results suggested that individuals differ in their ability to interact and that many who become leaders of very large organizations are able to interact with 12 to 15 or more assistants without feeling overburdened or pressured for time. Indik (1964) surveyed 116 organizations that ranged in size from 15 to 3,000 members and found that as organizations increase in size, they take on more operating members before they add new supervisors.

Confounds. Indik (1963, 1965a) cautioned that most generalizations about the effects of size are confounded by other factors. Two of these factors are the greater cohesiveness to be found in the smaller group, and the optimum size for the group’s task. In a survey of 5,871 workers from 228 factory groups that ranged from 5 to 50 members, Seashore (1954) found that the smaller groups were also more cohesive. The same was true for the conference groups studied by N. E. Miller (1950).

As was noted, demands on a leader’s initiatives increase along with the group’s size, and the potential of the leader or members to interact individually with one another decreases as the group enlarges. If additional members are superfluous and unnecessary as far as the completion of a team’s task is concerned, effectiveness and satisfaction are likely to suffer with an increase in the number of members. For any given task, there is an optimum-size team. Two people or even one person may be adequate and optimal for many tasks; five or six appear to be optimal for discussion groups (Bass, 1960). A larger number of different kinds of experts are likely to be needed for complex tasks whose completion requires skills and knowledge from many disciplines. The leader may need to deal with teams that are suboptimal in size or too large for the team’s task. When the team is too large for the task, the leader may need to initiate more structure so members do not get in each other’s way. When the team is too small for the task, the leader may need to provide for more time and resources or reduce the team’s goals.

Some groups in a large organization are seen as more valuable and critical to the organization’s success than are other groups. For example, line groups are likely to be considered more important than staff teams. Prestige also may vary. Thus the biology department may be perceived as more prestigious than the agriculture department at a university. Groups of skilled craftsmen may be thought of as more prestigious than groups of assembly line operatives. The reputations of groups of the same type may vary as well. For instance, one biology department may be viewed as ossified, while another is seen as being at the forefront of the field. Similarly, one group of skilled craftsmen may be seen as quarrelsome, recalcitrant, and hard to please, whereas another group may be considered highly efficient, competent, and dependable. Fried (1988) showed that within organizations like hospitals, the relative power of the nurses group, administrative staff, and physicians’ group were seen, particularly by the nurses, to depend on the centrality, nonsubstitut-ability, and coping with uncertainty of their respective roles.

Leadership within these different groups is likely to be affected in several ways. It will be easier to attract and hold members in the groups that have higher status and esteem. Members of these more highly valued groups will have relatively more influence with their leaders. In turn, their leaders will have more influence when they represent their groups in dealings with higher authority and with representatives of other groups at the same organizational level.

Functionally Diverse, Cross-Functional, and Multi-functional Teams. Leading a faculty group from different departments and disciplines is described as akin to herding cats. Yet diversity of education, profession, interest, knowledge, abilities, and departmental location in organizations is commonplace. Such functional diversity is witnessed in bringing together, on a regular or ad hoc basis, the vice presidents from the different divisions of the organization to generate policy suggestions; the scientists, engineers, and production heads to staff a functionally diverse team to innovate a new product; or the psychologist, social worker, psychiatrist, and nurse to discuss treatment of a mental health patient. Functionally diverse teams are expected to make better, more informed decisions but have a harder time reaching consensus. They help the leadership by facilitating organizational processes (Bantel & Jackson, 1989). They can help the top management interpret environmental ambiguities and reduce uncertainty (Zaccaro, Rittman, & Marks, 2001). As expert teams, they contribute to surveillance of the outside environment for the leadership and provide boundary spanning (Ancona & Caldwell, 1988). The leaders of cross-functional teams need to be technically competent and particularly skillful politically and interpersonally. They need to understand how the different functions are relevant to the success of the team (Yukl, 1998). Additionally, Jassawalla and Sashittal (1999) suggest, cross-functional team leaders should emphasize informal, intense meetings and exchanges of information. Forums should be provided for airing of issues and clarifications. Every member’s response to decisions should be treated as important. Members should be replaced if they are unable to overcome protecting their own turf or show mistrust of others or lack of commitment to collective intentions. Constructive conflict and delays should be tolerated.

Waldman (1994) noted some problems of multifunctional teams. At Honda, they generated procrastination and divisiveness (where harmony is prized). Leaders had to intervene to avoid costly delays. Waldman mentions seven roles of these leaders: (1) careful staffing; (2) coordinating and facilitating rather than directing; (3) encouraging members to form links with one another and the team’s clients; (4) establishing group-based evaluation and incentives; (5) anticipating and tolerating mistakes; (6) eliminating impediments to team performance; (7) aligning individual members’ and team goals. The leaders also need to maintain the vision, to be inspiring, to question assumptions, and to carry on in many other transformational ways.

The group’s norms (its definition of tasks, goals, the paths to the goals, and the appropriate relationships among members) strongly affect what a leader can accomplish in the group as well as who will emerge as the leader. In turn, the leader often has an impact on group outcomes by influencing the group’s norms.

Frame of Reference. Sherif’s conception of the social norm exerted a marked influence on research on leadership. In an autokinetic experience, Sherif (1936) seated a subject in a darkened room and asked the person to observe a spot of light projected on a screen. The subject reported the distance that the light appeared to move. The average distance for several trials was recorded as the subject’s individual norm. When the subject was later placed with a confederate of the experimenter who uniformly reported a distance that varied markedly from that reported by the participant, the subject tended to change his or her estimates to conform to the group norm. Asch (1952) obtained similar results when a subject was asked to judge the length of lines after six confederates of the experimenter had rendered judgments that defied the senses. The confederates uniformly declared that the shorter of two lines was longer. It was the norm of the confederates, not any single emergent leader, that influenced many of the subjects.

Other demonstrations of the effect of group norms showed how these norms moderate whether actual leadership behavior will be perceived as such. Thus, in an experimental comparison, Lord and Alliger (1985) found that the correlation of group members’ perceptions of emergent leadership with actually observed leadership behaviors was greater when norms were established for members to be systematic rather than remaining spontaneous. Likewise, Phillips and Lord (1981) demonstrated that if a group was described as effective but members were led to believe that the group’s success could be explained by other factors than the leader, the group’s performance had less of an effect on the members’ ratings of the leader.

The Group’s History of Successes or Failures. Some groups and organizations have histories of success and high performance that contribute to their esteem, while others have histories of failure and low performance. For instance, different United Fund agencies were found by Zander, Forward, and Albert (1969) to be consistently successful or consistently unsuccessful in meeting the goals of their fund drives. In the same way, Denison (1984) reported consistencies in the rate of return on investments by companies over a five-year period. Some companies tend to do well continually; others always do poorly. Histories of success give rise to norms of success and high performance, while histories of failure give rise to norms of failure and low performance. Thus, Farris and Lim (1969) found that high-performance groups had higher expectations of their future success as groups than did low-performance groups. Leaders whose accession to office coincides with a failure when the groups have been accustomed to success will no doubt earn more blame than ordinarily. Conversely, leaders whose accession coincides with the success of previously failing groups will gain an unusual amount of credit, which may not be justified. According to experimental results obtained by Howell (1985), a role conflict condition will arise for members when performance norms are low but the leader is high in the initiation of structure, particularly in the pressure to produce.

Conformity and Deviation. Ordinarily, when a discrepancy exists between the opinion of one member and the rest of the group, the deviating member tends to move closer to the group norm. But if an extreme deviate refuses to yield, he or she will be rejected by the other members (Festinger, 1950, 1954; Schachter, 1951). Gerard (1953) and Berkowitz and Howard (1959) obtained results to indicate that leaders directed most of their communications to such deviates. If a deviate was unreceptive to accepting the majority point of view, the group tended to expel the deviate from the group psychologically. Raven’s (1959a) report of the results of an experiment noted that deviates would shift toward the norm if they could express their opinions both privately and in public. Presumably, the leader could make a difference by encouraging such expression by the deviates.

Conformity to Norms and the Leader. Scioli, Dyson, and Fleitas (1974) found that when conformity was demanded by college groups, the most dominant members became the groups’ instrumental (task-oriented) leaders. Thibaut and Strickland (1956) obtained results indicating that as the group’s pressure to conform increased (often pushed by the leader), more members increased in conformity under a group set, while more decreased in conformity under a task set.5 At the same time, McKeachie (1954) reported that the members’ conformity to the norms of their groups and liking for the groups were greater in leader-oriented than in group-oriented classes.

Newcomb (1943) conducted a study of social values on a college campus. He found that the most influential members represented the dominant values of the campus. Those who conformed in conduct but not in attitude possessed social skills but maintained close ties to their families. Those who conformed in attitude but not in conduct tended to lack social skills but regarded conformity of attitudes to be a mark of community acceptance and superior intelligence. Similarly, Sharma (1974) found that Indian students who were activists and prominent as leaders of demonstrations were concerned primarily with student issues, not with social change. The attitudes of these student activitists tended to reflect the traditional values of their communities regarding religion, caste, marriage, and family. Likewise, in a study of modernization in India that sampled 606 heads of households engaged in agriculture, Trivedi (1974) found that although opinion leaders may have accepted innovations in agriculture, they, like Sharma’s (1974) student activists, adhered to traditional religious beliefs and convictions. They differentiated agricultural from religious activities more fully in the process. (But in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s and in France in 1968, as in China in 1919 and 1989, the norms of student activists placed them in the vanguard of reform and revolutionary change.)

In a Hungarian study, Merei (1949) formed groups that were composed of submissive nursery school children. When placed in separate rooms, each group developed its own role structure, rules for play, and routine of activities. After these had become stabilized, a child with strong propensities to lead in play activities was introduced into each group. Although the new members were widely successful in gaining leadership positions, they were not able to change the norms and procedural rules of the groups. The groups had more of an impact on the leaders than the leaders had on the groups. Consistent with this finding, Bates (1952) showed that the closer that the behavior of individuals comes to realizing the norms of the group, the higher these individuals’ likely position as leaders in the group. However, many other investigators found that group leaders ranked higher in the assimilation of group norms because they were highly influential in the formation of the norms.6 Although leaders may be influential in establishing group norms, once the norms are adopted, they are expected to observe the norms (Hare, 1962).

O. J. Harvey (1960) found that formal leaders conformed more to group norms than did informal (sociometrically identified) leaders or other group members, especially under conditions of uncertainty. Mulder (1960) also found that the judgment of leaders was most influenced by other members when they, the leaders, were appointed in an ambiguous situation. But the emergent, informal leaders were the least influenced in the ambiguous situation without established norms.

When the Leader Can Deviate. The fact that leaders tend to be prime exemplars of their groups’ value systems is not to suggest that they are slaves to the groups’ norms (Rittenhouse, 1966). In fact, they may deviate considerably from the norms in various aspects of their conduct. In a study of sociometric cliques among teachers, Rasmussen and Zander (1954) found that leaders were less threatened than were followers by deviation from their subgroup’s norms. Leaders appeared secure enough to feel they could depart from the norms without jeopardizing their status. Similarly, Harvey and Consalvi (1960) found that the member who was second highest in status as a leader of a group was significantly more conforming than was the member who was at the top or bottom of the status hierarchy. The leader conformed the least, but not significantly less than the lowest-status member. Likewise, Hughes (1946) observed that members of industrial work groups let rate busters know in forceful terms that their violation of group norms would not be tolerated. However, the leaders of the work groups were allowed more freedom to deviate from certain group norms than were other members whose positions were less secure.

The Leader’s Need for Early Conformity. As was detailed in previous chapters, Hollander (1958, 1960, 1964) suggested that the early conformity of leaders to the norms of their groups gains for them idiosyncrasy credits that enable them to deviate from the norms at later dates without their groups’ disapproval (Hollander, 1964). The lesson for would-be leaders who wish to bring about changes in groups is that they must usually first accept the groups’ current norms to be accepted. Practical politicians often can bring about more change by first identifying with a country’s current norms and then moving the country ahead with statesmanship that takes the country where it would not have gone without the politician’s direction. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s leadership of the isolationist United States into World War II is an illustration.

Acceptance and the Leader’s Freedom to Deviate. In a study of personnel in the U.S. Air Force, Biddle, French, and Moore (1953) found that the closer the attitudes of crew chiefs were to the policies of the U.S. Air Force, the stronger were their attempts to lead. Chiefs who accepted their role as supervisors used their influence to further the institutional goals and purposes. But the amount of such attempted leadership was not related to the extent to which the chiefs were accepted by the crew members. However, crew chiefs who were accepted by their groups deviated further from the norms and policies than those who were not accepted.

Effects of the Group’s Goals. Without doubt, the group’s purposes, objectives, or goals are predominant as norms of the group. Studies of experimental groups indicate that members readily accept or commit themselves to the defined task and seem to develop other norms in support of the norms of the task. Once the members understand and agree on the group’s goal, the goal operates as a norm against which the members evaluate one another’s potential for leadership. Goode and Fowler (1949) observed, in a small industrial plant, that the informal groups supported the company’s production goals despite the workers’ low satisfaction with their jobs. The authors attributed this outcome to leadership that provided clear statements of the groups’ goals; clear definitions of the members’ roles; and strong, congruent group pressures toward conformity from within and outside the informal group.