1

Introduction

God does seem evidently to be throwing down the glory of all flesh. The greatest powers in the kingdom have been shaken.

William Goffe at the Putney Debates, 28 October 16471

On 30 January 1649, King Charles I stepped onto a platform that had been specially erected outside the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace in London. Wearing two shirts so he would not shiver in the cold and be accused of trembling with fear, Charles addressed the assembled crowd. He was, he claimed, about to die as ‘the martyr of the people’. The king then turned to his executioner, instructing him to wait until his final prayers had been said, at which point Charles would stretch out his hands as a sign that he was ready to die. William Juxon, the bishop of London, accompanied the king on the scaffold and handed him a cap, under which Charles pushed his hair to leave his neck bare for a clean cut. The king announced that he was going ‘from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown; where no disturbance can be’. Then, after removing his doublet and pendant of the Order of the Garter—the item of jewellery that signified his membership of the most august chivalric order in the land—Charles prayed for the last time and stooped to place his head on the block. He thrust out his hands. The executioner’s blade, in one blow, severed the king’s head from his body.2

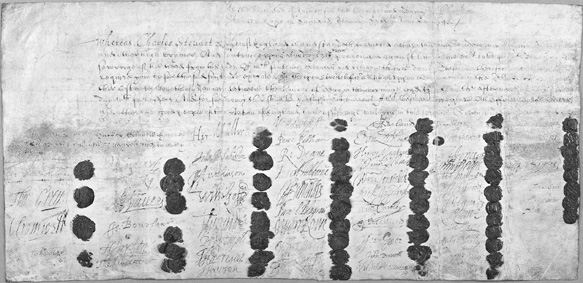

Charles had lost the English civil war, a devastating conflict that divided the nation during the 1640s, and that had been precipitated by the king’s economic and religious policies as well as the increasing intransigence between king and Parliament. This was underlined by Charles’s principled, or stubborn, adherence to the divine right of kings: the theory that God put Charles on the throne, so Charles answered only to God, not to his subjects or Members of Parliament. Charles had continued this intransigence in the wake of his military defeat, refusing to lower the authority and dignity of his kingly office as the nation searched for a post-war settlement. When Charles restarted the civil war in 1648, shedding further blood, it became clear to many of his enemies that a settlement would not be reached while the king remained alive. Charles was, they argued, guilty of treason. Following his trial, during which Charles refused to go along with the proceedings of a court whose authority he would not recognize, the king’s death warrant was signed. There were fifty-nine signatories. The third was Oliver Cromwell, who would later become lord protector. This book is about the fourth and fourteenth: Cromwell’s cousin Edward Whalley and Whalley’s son-in-law William Goffe. Just over a decade after they signed the king’s death warrant, Whalley and Goffe found themselves on the run to America. The thirty-eighth signatory, John Dixwell, would join them a little later.

The monarchy was restored in 1660, following a series of constitutional experiments in the Commonwealth and Protectorate of the 1650s. Many of those who had been prominent in those experiments—and the regicide that augured them—feared for their lives. In reality, the early Restoration settlement had a conciliatory tone: Charles II simply had to forgive many of those who had been active in the civil wars, Commonwealth, and Protectorate if he were to achieve a peaceful return to England. There was a grey area between those who definitely were going to be forgiven and those who definitely were not, and speculation continued right up to the trials of the regicides about whose crimes against the Stuarts had been so heinous that they would not be granted indemnity against prosecution. But some key figures were always going to be excluded from the forgiving and forgetting—what was called in a law of 1660 the ‘indemnity’ and ‘oblivion’. Among those who most definitely were not to be forgiven were the almost forty signatories of Charles I’s death warrant who were still alive at the Restoration.

Civil war

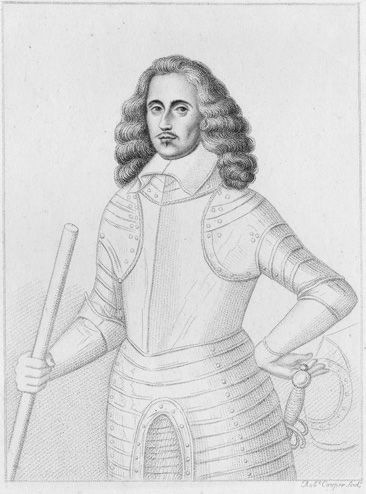

A report written to the lord chancellor at the Restoration of the monarchy highlighted Edward Whalley as ‘a great stickler against the king and Goffe another’.3 For a full understanding of why Whalley and Goffe had achieved this reputation, we need to explore their prominent roles in the twenty years prior to that Restoration. William Goffe (see Figure 3) came from a family divided over the issues of religious faith and loyalty to Stuart monarchs. On the one hand, the Goffes had a history of opposing the policies of the Stuart monarchy and dedicating their lives to the Puritan cause. William’s father, Stephen, had been active in delivering Puritan petitions to Charles I’s father, James I. (One such petition of 1603, for example, called for the abolition of bishops in church governance; the king later famously declared, ‘No bishop, no king!’) On the other hand, William’s elder brother (also called Stephen) supported the Royalist cause in the civil war and negotiated on the continent for troops on Charles I’s behalf. He was also chaplain to the Puritans’ bête noire, Archbishop William Laud, as well as to Charles I, Queen Henrietta Maria, and Charles II’s illegitimate son, James Scott, later duke of Monmouth. One account even suggests that it was this Stephen Goffe who passed on to Charles I’s sons the news of their father’s execution in 1649—an execution that Stephen’s own brother had been instrumental in orchestrating.4

William Goffe’s first significant act of opposition to Charles I was in 1642 when he contributed to a petition to the king insisting that Parliament should control the city militia in London. This was an important moment on the road to civil war, one point among many at which control over the nation’s military forces was under debate. Charles I, in the eyes of many Members of Parliament, had demonstrated consistently that he could not be trusted with such control—or at the very least Parliament should have sufficient military capacity to defend itself against any sinister encroachments by the king. In January 1642, indeed, Charles I had entered the Commons with his soldiers, attempting to arrest five MPs whom he considered to be particularly troublesome. The fact that, in Charles’s own words, these ‘birds’ had ‘flown’, pre-warned about the king’s arrival in Parliament, was a humiliating moment for the king. The Speaker of the House of Commons refused to tell the king where the five MPs had gone, while Charles had demonstrated that he could not be trusted to preserve the rights of Parliament to sit unimpeded by the will of the monarch. Riots broke out in London and Charles I was forced to flee. The king had lost his capital and a few months later Royalist troops faced Parliament’s soldiers at the first battle of the English civil war.

The king’s attempted arrest of the five MPs was the culmination of a decade and a half of tension between Charles I and many of his subjects. Charles’s elder brother and James I’s original heir to the throne, Henry, had been popular and charismatic, balancing martial prowess with interest in the arts. He was the consummate seventeenth-century prince. Charles, in contrast, was short and suffered from a stammer and in his younger years did not cultivate the charisma, political awareness, and contacts necessary for an effective future king. When Henry died unexpectedly in 1612, Charles was not fully prepared. Furthermore, he was exceptionally principled—a devout believer in the divine right of kings, that he was answerable only to God from whom his power and authority were derived. This could be lauded as a positive quality, had Charles not lived and reigned at a time when effective statecraft necessitated some degree of flexibility and cynicism. Charles was attempting to govern three kingdoms that had been religiously fractured since the previous century, and with an increasingly assertive Parliament whose frustration grew as their grievances were not redressed: an eleven-year period between 1629 and 1640. In such a sensitive and increasingly tense political and religious landscape, some tact or Machiavellian guile may have been more successful than excessive adherence to a principle.

Charles was especially forthright when it came to matters of religion. His emphasis on the ‘beauty of holiness’, administered by his equally obdurate archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, to many smacked of a return to the Roman Catholic faith. Since the break from Rome in the 1530s, Catholicism had been frequently tainted with images of immoral popes and priests who broke their vows and focused on secular and financial advancement instead of spiritual purity. In the British context, this was augmented by memories of the brutal execution of Protestants by Queen Mary—300 in three years—during the brief return to Catholic rule in the 1550s. Later, when the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was discovered and the spectacular immolation of James I and Parliament thwarted—Guy Fawkes and his co-conspirators had packed with explosives a cellar under the king’s opening of Parliament on 5 November—the Catholic faith was further associated with terror and assassination. In the eyes of many Protestants, not least those on the extreme Puritan wing, for Charles I to look and sound like a Catholic, or even sympathetic to Catholicism, was to threaten the Protestantism of his nation and to put its salvation in jeopardy. Being fed up about taxation is one thing—and can indeed lead to open rebellion—but the prospect of eternity in Heaven or Hell was a matter more likely to cause subjects to take up arms.

Charles found this in 1637 when he tried to introduce Laud’s new Prayer Book into Scotland. The Presbyterian Scots rebelled against the imposition. They were much more sympathetic to John Knox’s anti-bishop, austere, and scripture-based Calvinism than William Laud’s episcopal, ornate, and ceremony-heavy High Churchmanship. Charles I attempted to impose the Prayer Book by force and he faced down the Scots in the First Bishops’ War of 1639: the twenty thousand crown-raised forces were deemed so unimpressive that the Scots were left alone at the Pacification of Berwick. The conflict reignited the following year, even though Parliament had refused the king’s request for funds for a larger army. The Scots invaded the north of England and Charles was forced to sign the Treaty of Ripon, under whose terms the king had to pay £850 a day to ensure that the Scottish army remained in Newcastle, Northumberland, and County Durham without marching further south. At this critical point the king could no longer dissolve Parliament as he needed it to raise the money, through taxation, required to pay the Scots.

In 1641, therefore, Parliament took advantage of the fact that it could not be closed down and issued further complaints to the king, as well as putting Charles’s friend and chief minister, Thomas Wentworth, earl of Strafford, on trial for treason. Parliament called for the abolition of monopolies and Ship Money, a levy traditionally raised on the coasts to strengthen the navy but which Charles had extended to inland counties, as well as the suspension of the prerogative courts (such as the Star Chamber and the Ecclesiastical Court of High Commission, which had previously punished Puritans). Members of Parliament also called for the right to vote against the king’s desire to dissolve Parliament, for Parliament to be summoned at least every three years (a challenge to a system that had allowed Charles to rule without Parliament for eleven years), and for Parliament to be able to choose the king’s ministers. Whereas Charles previously had been able to dissolve Parliament in the face of such temerity, now he had no choice but to live with MPs’ grievances and increasingly confident, indeed strident, demands.

A further crisis point was reached in October 1641. There was a rebellion in Ireland, during which thousands of Protestants were massacred in Ulster. Charles I and Parliament were united over the necessity of quelling the rebellion but were divided over who should have command of the army doing that quelling. The king automatically assumed that he would have overall command. Yet MPs, suspicious of a king who had ruled without them for eleven years and increasingly confident about shaving away his powers, feared Charles would use the army against them. John Pym, one of the most assertive MPs, demanded that Charles sacrifice one of his prerogative powers and allow Parliament to decide who would control the army. ‘By God, not for an hour’, came Charles’s reply. The following month, Parliament presented even more grievances to Charles in the ‘Grand Remonstrance’ and, once again, demanded that it should choose the king’s advisers. In essence, the two sides were becoming further and further entrenched, with demands being made by one side to which the other would never agree.

It was at this point in January 1642 that the king arrived in Parliament to arrest five of the more recalcitrant MPs. In June 1642, Parliament issued yet more demands to the king who by now had fled his capital: the church was to be reformed, as Parliament—not Charles or Laud—wished; the king’s ministers and all affairs of state were to be approved by Parliament; Parliament was to control the army. The king, however, was never going to concede these fundamental monarchical rights. In June 1642 he issued the Commission of Array, calling on those subjects loyal to him to fight against the rebellious Parliament. Then in August he rode to Nottingham and raised the royal standard, the king’s flag and a rallying point for Charles’s loyal soldiers. Parliament, in turn, issued the Militia Ordinance, meaning that lord lieutenants were appointed by Parliament and hence those militias stationed in counties—the only readily available land forces in peacetime in a country without a standing army—were under Parliament’s control. Each side was preparing the military forces necessary for a civil war and the Battle of Edgehill followed in October 1642.

Both Edward Whalley and William Goffe fought with distinction in the English civil war and progressed rapidly through the military ranks. Goffe quickly become a captain, then colonel. Whalley, similarly, was a cornet (the lowest grade of commissioned officer in a cavalry troop) in Parliament’s sixtieth regiment of horse in August 1642, before becoming captain by March 1643, then a major in Oliver Cromwell’s own regiment of horse. Whalley was a first cousin of Cromwell—his mother, Frances, was daughter of Sir Henry Cromwell of Huntingdonshire. After fighting at the Battle of Gainsborough in 1643, Whalley served as lieutenant colonel at Marston Moor. Then, following the formation of the New Model Army, a force more professional than the previous Parliamentary army and one devoted to an offensive war against Charles I, Whalley fought at the decisive Battle of Naseby in 1645. He was in the front line of the Parliamentary army’s right wing, tucked just inside the outermost Parliamentary forces that struggled through the warren to the east of Turnmoore Field.5 Whalley was responsible for two divisions that defeated two Royalist divisions of horse, for which he was given a commission as colonel of horse. Whalley also fought at Langport the following month and, the following year, proved himself adept at siege warfare. He helped besiege Bridgwater (July 1645), Sherborne Castle (August 1645), Bristol (August–September 1645), Exeter (February 1646), Oxford (March 1646), and Banbury (May 1646). Whalley was also active at the siege of Worcester in July 1646, though he departed before the city surrendered.

Even though the king surrendered to the Scots at Newark in 1646 and even though Parliament won the civil war, Charles I was still the king and was still determined not to concede his power and authority. During the following two years the army and Parliament tried to reach a settlement with Charles, just as MPs had tried to wrestle away some powers from a king they could not trust in the two years before the civil war. Just as the proposals in 1646–8 echoed those of 1640–2, so too was Charles I’s response characteristically stubborn.

Prisoner and guard

For two and a half months of this period, from 24 August until 11 November 1647, Charles I was held prisoner at Hampton Court. Edward Whalley guarded him. But the man who had been so prominent in helping defeat Charles in war was not totally enthusiastic about his new role as the king’s gaoler. This was, in large part, because the king was not really a prisoner. Whalley wrote to John Lenthall on 15 November 1647 lamenting that he was ‘not to restrain [Charles] from his liberty of walking: so that he might have gone whither he had pleased’ or ‘to hinder [Charles] from his privacy in his chamber, or any other part of the house: which gave him absolute freedom to go away at pleasure’. Whalley complained that Hampton Court contained one and a half thousand rooms and he simply did not have sufficient forces to guard the king properly. All he could do, therefore, was to keep as close an eye on Charles as he could during the day and then place sentinels outside the king’s chamber once he had gone to bed.

Whalley identified another problem that was impeding his duty: Charles was allowed in his presence too many gentlemen of his bedchamber who were loyal to him. These were men like Captain Legge, former governor of Oxford, or John Frecheville, whom Whalley referred to as an ‘active enemy’ and who played tennis with the king at Hampton Court.6 If there were plans afoot for Charles to escape, Whalley complained, these gentlemen were unlikely to divulge them to the king’s captor. Whalley’s final concern was that of his own reputation. If Charles did ‘escape’—a term Whalley was reluctant to use because the king was not properly a ‘prisoner’—then Whalley would be considered at best incompetent and at worst a traitor to the Parliamentary cause.

Whalley’s concerns were written four days after Charles I actually did ‘escape’—or ‘leave’ in Whalley’s terms—his custody at Hampton Court. He was writing to defend himself against any accusations that he had been complicit in the king’s departure and to explain why Charles had left so effortlessly. The day of the king’s escape had been one set aside for Charles to write letters in his bedchamber, which he would normally do until five or six o’clock in the evening. At around five o’clock, Whalley arrived at the room next to the king’s bedchamber, where the king’s gentlemen informed Whalley that Charles was still writing letters. Whalley waited until six o’clock; still the king did not appear. Whalley was assured that the king had a particularly long and important letter to write to the Princess of Orange. By seven o’clock, Charles still had not appeared. Whalley suggested that the king might be ill but was informed that Charles had given strict orders that he not be disturbed. Whalley looked through the keyhole to see if he could see the king but could not do so. By eight o’clock, Whalley went to the keeper of the privy lodgings to accompany him to the king’s bedchamber by another route. When they arrived at a room next to the king’s bedchamber, they discovered Charles’s cloak lying on the floor. Whalley took the cloak back to the king’s gentlemen and, at this point, insisted that he be granted access to the bedchamber, ‘in the name of Parliament’. Whalley agreed, however, that he would stand at the door instead of entering the bedchamber. But this was sufficient to determine that Charles had gone. Whalley instituted a search of nearby grounds and houses but his men found nothing.

Charles had travelled to the Isle of Wight, apparently fearing for his personal safety, and worried that there was a plot to assassinate him at Hampton Court. This plot allegedly was being laid by the more radical elements of the New Model Army and was communicated to the king by a letter secretly sent to Hampton Court and read to the king by Whalley himself.7 Whalley protested that he had no part to play in any such plot: ‘I was much astonished, abhorring that such a thing should be done, or so much as thought of, by any that bear the name of Christians . . . I was sent to safeguard, and not to murder him . . . I would first die at his foot in defence’.8 The irony of these words would become clear over the next year or so.

‘A man of blood’

One of the men most significant in hardening attitudes towards Charles I, and expediting his trial and execution, was William Goffe, the husband of Whalley’s daughter, Frances. Goffe was prominent at the Putney Debates that began in October 1647, while the king was still at Hampton Court. These debates took place between so-called ‘Leveller’ agitators from the regiments of the New Model Army and the ‘grandees’ in command of that army. While the agitators were concerned mainly with the drafting of a new political constitution, legal reforms, and some extension of the right to vote, they could not avoid the issue of how Charles I should be treated. There were complaints that the ‘grandees’ had been too lenient and servile in their dealings with the king. Goffe called for a prayer meeting before the debates began—a common feature of Puritan worship wherein the godly would seek divine guidance in making decisions or healing divisions—and found that his antagonism towards the king deepened through prayer and his contemplation of scripture.

Goffe firmly believed that he was living through the End of Days. Fuelled by his passionate millenarianism—the belief that Christ was about to return to earth and rule as king alongside the saints, with the just recalled to life—Goffe was determined not to deal with Charles the Antichrist. Instead negotiations should cease and a solution be found that would save the souls of true believers, before Christ’s Second Coming. ‘God does seem evidently to be throwing down the glory of all flesh’, Goffe insisted at Putney; ‘it seems to me evident and clear that this hath been a voice from heaven to us, that we have sinned against the Lord in tampering with his enemies’.9 He was not without his sympathizers: Henry Ireton, Cromwell’s son-in-law, remarked that Goffe ‘hath never spoke but he hath touched my heart’. Cromwell himself told Goffe that ‘I am one of those whose heart God hath drawn out to wait for some extraordinary dispensations, according to those promises that he held forth of things to be accomplished in the former time’.10

Goffe’s millenarian principles remained just as strong the following April at the Windsor Prayer Meeting, a two-day gathering of the New Model Army’s Council of War, during which its Puritan leaders were to interrogate their consciences and ask for divine guidance in ascertaining the root of, and solution to, the nation’s plight. Once again Goffe relied on scripture for his reasoning, especially the ‘Warning against the invitation of sinful men’ in the Book of Proverbs: ‘Do not go along with them, do not set foot on their paths; for their feet rush into evil, they are swift to shed blood’ (Proverbs, I, 15–16). The implication was that negotiating a settlement with the monarch was akin to dealing with those who ‘lie in wait for innocent blood . . . ambush some harmless soul . . . [and] swallow them alive, like the grave’ (Proverbs, I, 11–12). William Allen, former adjutant-general of the army in Ireland, was present at the meeting and noted that those in attendance were convinced that they had ‘departed from the Lord’ by negotiating with Charles. Goffe used Wisdom’s Rebuke in verse 23 of the First Book of Proverbs, in particular, to cement the conviction of those present that dealing with the king had not just been a mistake, it had been sinful: ‘Repent at my rebuke! Then I will pour out my thoughts to you, I will make known to you my teachings’. If those present at Windsor did not repent and did not mend their ways, ‘calamity’ would overtake them ‘like a storm’; ‘disaster’ would sweep over them ‘like a whirlwind’ (I, 27). The results of Goffe’s intervention were dramatic:

. . . it had a kindly effect . . . upon most of our hearts that were then present; which begot in us great sense, shame, and loathing ourselves for our iniquities, and justifying the Lord as righteous in his proceedings against us: and in this path the Lord led us not only to see our sin, but also our duty; and this so unanimously set with weight upon each heart, that none was able to speak a word to each other for bitter weeping, partly in the sense and shame of our iniquities of unbelief, base fear of men, and carnal consultations (as the fruit thereof) with our own wisdoms, and not with the word of the Lord, which only is a way of wisdom, strength and safety, and all besides it ways of snares: and yet were also helped with fear and trembling, to rejoice in the Lord . . .11

It was a short step then to cast Charles Stuart as a ‘man of blood’, the implications of which were rhetorically to strip Charles of his crown—he was a ‘man’, not a ‘king’—and through providence and scripture (Numbers, XXXV, 33) to seek revenge appropriate for a man who had shed the blood of his own subjects: the desire of blood for blood would bring the king to trial, and ultimately to his execution.12

It was abhorrent enough that Charles had fought against his own people in the first civil war, but even worse when, having escaped from Hampton Court, he signed a military Engagement with the Scots in 1647 (securing their military support in exchange for some proposed religious concessions) and caused even more deaths by starting the second civil war in 1648. Charles garnered support, especially in south Wales, Kent, and Essex, from former Royalists and new Royalists frustrated with the lack of pay for soldiers from Parliament and the increasing prominence of the New Model Army in Parliament’s decision making. The bloody battles and sieges that ensued further hardened opinion against the king. Whalley himself fought in the summer of 1648 at the Battle of Maidstone and at the siege of Colchester, commanding the cavalry that chased the earl of Norwich into Essex. It was now very clear that Charles I could not be trusted to accept that defeat in war meant concessions in power and authority. Attempts at reaching a settlement had failed. In the view of the Puritans, with the End Times fast approaching and with the man of blood causing the spillage of even more blood, it seemed that the only option was to put Charles Stuart on trial.

To ensure that Parliament would be packed full of MPs who would vote to try the king, it was necessary to ‘purge’ it of those reluctant to follow such a path. Colonel Thomas Pride stood at the doors of Parliament in December 1648, turning away those MPs who would not vote to put the king on trial. One account has suggested that Whalley stood by Pride’s side as the purge took place.13 This is perhaps a metaphorical reference, as Whalley did sit subsequently on a committee justifying Pride’s, and the army’s, actions.14 The House of Commons passed an Act appointing a High Court of Justice on 6 January 1649, though the court did not meet formally until 20 January. Whalley sat as a commissioner, attending all but one day (12 January) of this process. Goffe, too, was a commissioner. Charles was accused of high treason, of shedding the blood of innocent subjects, and found guilty. On 27 January the court’s decision was made public: Charles was to suffer the death penalty. Edward Whalley and William Goffe were two of the fifty-nine men who put their signatures to the king’s death warrant (see Figure 4).

Interregnum and Restoration

The judicial execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649, the only time in British history that a king had been put on trial and then put to death, left a blank canvas on which new political arrangements could be drawn. Whalley and Goffe were present and prominent throughout these constitutional experiments, while at the same time retaining their military roles. Goffe commanded a regiment against the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar in September 1650, when Cromwell noted that ‘at the push of pike’ Goffe ‘did repel the stoutest regiment the enemy had there’,15 and resisted attempts to put Charles II on the throne by fighting at the Battle of Worcester in September 1651. By 1650 Whalley was commissary general and commanded four regiments of horse. He, too, distinguished himself at Dunbar and Worcester. At the former he was wounded in the hand and wrist and his horse was killed but, undaunted, Whalley found another horse and resumed fighting.

Both Whalley and Goffe were also active in non-military affairs in the 1650s. For example, they backed John Owen’s proposal to the Rump Parliament—a derogatory term for the ‘backside’ of the Parliament left after Pride’s Purge—to create a state church characterized by wide, if not total, toleration.16 Following the revolutionary promise of the regicide, Whalley, like Oliver Cromwell, grew impatient with the Rump’s apparent self-serving tardiness when it came to constitutional reform. So he presented a petition from the army to encourage major changes and, when the Rump’s reforms were not deemed sufficiently extensive, Whalley backed its dissolution in the spring of 1653. Goffe was also present at the dissolution of the next ill-fated assembly, the Barebones Parliament, in 1653. Bussy Mansell, who represented Wales in the assembly, reported that Goffe was one of those who forced out, with ‘two files of musketeers’, those MPs who refused to leave.17 Whalley represented the county of Nottinghamshire in the Protectorate Parliaments; Goffe sat for Great Yarmouth, in addition to being a ‘trier’; that is, someone screening potential churchmen for their adherence to the principles of the new Puritan regime. Goffe also remained concerned with military matters. In March 1655, he assisted the crushing of the Royalist insurrection, Penruddock’s Rising. Later, in July 1655, there were suggestions that the regular army be cut substantially in size, which Goffe opposed.18

Whalley and Goffe reached the summit of their political careers in 1655: each was appointed a major general in Cromwell’s constitutional experiment, the ‘Rule of the Major Generals’. Cromwell’s aim was to establish godly rule at gunpoint, with the country divided into districts, each ruled by one of the militant godly. Goffe was put in charge of the counties of Sussex, Hampshire, and Berkshire. Whalley was given Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, and Warwickshire. They distinguished themselves as two of the most earnest major generals in an ultimately ill-fated project. It was ill-fated for a number of reasons. First, local populations were inimical to having authority foisted on them from London even if, like Goffe, the major general had family connections to the area. Second, patrons of alehouses and theatres did not take kindly to their entertainments being curtailed by the righteous. Third, an unpopular Decimation Tax was earmarked to fund the major generals scheme but proved difficult to collect. Goffe himself found the whole project exhausting. He reported that he was ‘discouraged’ and ‘so much tired that I can scarce give an account of my doings’.19 Whalley was keen on moral reform, though he was hampered in his efforts by local magistrates. He had some successes, for example, in arresting vagrants and closing down unlicensed alehouses, but the ‘Rule of the Major Generals’ ended in January 1657—another unsuccessful attempt in the search for a constitutional settlement in the 1650s.

A new constitutional proposal was tabled in 1657: the Humble Petition and Advice. Once again, Whalley and Goffe were present. Part of this proposal was an offer of the crown to Cromwell. Whalley and Goffe both initially rejected the idea, though we should not overestimate the vehemence of their resistance. While Whalley was a teller of the ‘noes’ when it came to a vote on the offer of the crown, John Reynolds, an Irish MP, reported in March 1657 that ‘honest Whalley and Goffe were moderate opposers [to kingship], almost indifferent’.20 Cromwell himself refused to lift up the crown that, as he put it, ‘God had lain in the dust’. By April 1657, however, it appeared that Whalley and Goffe were becoming less averse to the idea of kingship, in name at least. Whalley declared that he could ‘swallow’ the idea of the ‘title’ of king, if it meant that the best parts of the Humble Petition and Advice were kept.21 In the event, the following month Cromwell once again refused the crown.

One of the features of the Cromwellian regime most common in the popular imagination is the ‘abolition’ of Christmas. Again, Whalley and Goffe were active in the regulation of a festival considered to be both extravagant and redolent of the survival of a Catholic ceremony that had no basis in scripture. On 25 December 1657, the diarist John Evelyn was celebrating Christmas in the chapel of Exeter House on the Strand in London when, during Communion, the chapel was surrounded by Cromwell’s soldiers. The congregation was kept imprisoned, albeit fairly comfortably in Evelyn’s case: he was detained in a house where he was able to dine with the countess of Dorset. In the afternoon, both Whalley and Goffe arrived to examine the congregation and to imprison some of them. Evelyn was asked ‘why contrary to an ordinance made that none should any longer observe the superstitious time of the Nativity (so esteemed by them) I durst offend, and particularly be at common prayers’. They were particularly irked that the congregation was praying for Charles Stuart, when there was no basis for this in scripture. Evelyn’s response was that they were praying not for Charles Stuart but for ‘all Christian kings, princes and governors’. This did not placate Whalley and Goffe, however, as they claimed Evelyn and the congregation were therefore praying, in effect, for the Catholic king of Spain, ‘who was their enemy, and a Papist’. Evelyn was set free but not before Whalley and Goffe had spoken ‘spiteful things of our blessed Lord’s nativity’—presumably about Evelyn’s interpretation of the Christmas celebration rather than the birth itself.22

Between the dissolution of the Second Protectorate Parliament in February 1658 and Cromwell’s death seven months later, one observer suggested that Goffe was in such ‘great esteem and favour at court, as he is judged the only fit man to have Major General Lambert’s place and command, as major general of the army’. (John Lambert had been a leading figure in Cromwell’s Council of State earlier in the 1650s, as well as a popular military leader, but by 1658 he had fallen out of favour with the lord protector.) While this observer was critical of Goffe’s ‘evil tincture of that spirit that loved and sought after the favour and praise of man more than that of God’, he went so far as to suggest that Goffe’s personal trajectory one day might take him to the protectorship itself.23 In the event, just before Cromwell died on 3 September 1658, he named his son, Richard, as his successor.24 Whalley and Goffe were reported to be in attendance at Cromwell’s deathbed; Goffe was one of the chief mourners at his funeral.25

Whalley and Goffe were both supporters of Richard Cromwell’s protectorship: Whalley sat in Richard’s ‘other house’—Parliament’s upper chamber that had replaced the House of Lords—during the Third Protectorate Parliament of 27 January to 22 April 1659. But Richard’s was a short-lived rule. A country gentleman with little support in the army, he soon found himself facing an army mutiny led by General Charles Fleetwood. The army began to demand a return to republican rule, for the payment of arrears, and a promise of indemnity for any actions they had carried out. The Third Protectorate Parliament lasted only three months: Parliamentary republicans, supported by the army, forced Richard to dissolve it. Lambert, the man to whom Goffe had been mooted as a potential successor, requested the return of the Rump Parliament—that is, those members of the Parliament of December 1648 which had put Charles I on trial. Lambert further called for the establishment of a commonwealth, ‘without a King, single person, or House of Lords’. On 7 May 1659 Richard acquiesced to demands from the Council of Officers and reinstated the Rump. Twelve days later, Parliament elected a new Council of State. Within days Richard Cromwell resigned.

Different civilian and military forces now competed to fill the power-vacuum that had been created. Having called for its reinstatement, Lambert and his fellow soldiers grew impatient with the Rump, with disputes arising over the granting of indemnity and the appointment of army officers. Lambert expelled the Rump on 13 October and began a period of martial rule. Two months later the navy mutinied, Lambert’s support collapsed, and the Rump returned. Amidst this chaos, the figure of George Monck appeared to establish some kind of political and social order. Commander of the army in Scotland, Monck had refused to meet with Whalley and Goffe who had themselves attempted to rally support for Lambert’s expulsion of the Rump in October. On 21 February the moderate Monck reinstated those MPs who had been purged in December 1648. The Long Parliament was back.

With the restored MPs outnumbering those of the Rump, various measures were passed to begin settling the nation: a new moderate Council of State was elected; figures associated with the army, like Whalley, had their commissions removed; Monck was made commander-in-chief of the army; and, most importantly, the Long Parliament dissolved itself as Monck began negotiating with Charles I’s son to return to England as King Charles II. New elections were called to allow MPs to assemble and ascertain the terms of this Restoration. On 4 April 1660 Charles made a series of promises that would smooth his return: soldiers’ arrears would be paid; a general pardon, with some key exceptions, would be proclaimed; and some religious toleration would be allowed. On 8 May 1660 Charles II was proclaimed king—the monarchy was restored.