6

The spirit of the regicides, liberty, and American national identity

Memory plays many pranks with history. Its products are attractive, but as a rule unreliable, as like a snowball on a warm day in winter, the volume increases with each revolution on the hill of time. Still it supplies the gloss and spangles used to dress statistical matter . . . By blending fact and fancy it is possible to weave a narrative which entertains and at the same time instructs the reader. Those who believe it can; those who doubt it may;—so let it go at that.

W.H. Gocher, Wadsworth: or The Charter Oak (1904), 48

The election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800 represented a victory for those who had spent the previous two decades exalting the regicides in order to drive out the vestiges of monarchism in the new American Republic. Jefferson’s simple inauguration—he was the first president to walk to the ceremony and he wore plain clothes—shunned the pseudo-monarchical pomp of previous Federalist administrations. He now appealed for conciliation between Federalists and Republicans, the hostility between whom had raged through the 1790s, providing the political backdrop for some of the more excitable rediscoveries of the regicides. At first sight, the early decades of the nineteenth century were not ripe for continued interest in Whalley and Goffe. Newly freed American minds were looking optimistically westwards, not back across the Atlantic to English (now somebody else’s) history. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 provided Americans with over 800,000 square miles into which they could expand; the Lewis and Clark expedition commissioned in the same year afforded an opportunity to map and explore potential trading routes to the west of the Mississippi River. Independence from Great Britain also brought freedom from colonial restrictions on trade, manufacturing, and shipping; a new spirit of optimism was reflected in economic growth, the pursuit of new career opportunities, excited resettlement through westward migration, and the development of a new urban environment. Perhaps this explains why, by April 1819, the graves that were thought to belong to the regicides had become so neglected and overgrown that Ezra Stiles’s grandson, Jonathan Leavitt, only stumbled across them in search of a lost ball.1

We need not be so pessimistic. Leavitt had read his grandfather’s History, had previously tried to find the regicides’ graves, and thought that he had come across ‘the bones of the mighty’. And beyond the confines of the New Haven burial ground, Whalley and Goffe were not shunned from a new American consciousness that looked increasingly westward towards the Pacific Ocean rather than the former English colonies on the Atlantic coast. Several factors combined to ensure that two old English Puritans from the mid to late seventeenth century played a prominent role in the development of a new American national identity. From June 1803 when Reverend Isaac Jones, a descendant of William Jones, was the first to etch on the Judges Cave an inscription, ‘Opposition to tyrants is obedience to God’,2 to G.H. Durrie’s painting of that very cave fifty years later, the regicides played an important role in American culture. The association between regicide and revolution remained of especial interest among those whose nation was forged in its own revolution against an English king. The drive westwards also inevitably brought further conflict with the indigenous populations, evoking echoes of King Philip’s War, and affording a new relevance to the story of the Angel of Hadley. Authors’, readers’, and artists’ taste for the supernatural and republican liberty further ensured that English regicides found their place within a framework of American literature and art.

British to American literature

Early nineteenth-century British representations of the regicides in America were not overly celebratory. Even Ebenezer Elliott, the strident political reformer and author of The People’s Anthem (‘When wilt Thou save the people? . . . Not thrones and crowns, but men!’) in Kerhonah (1835) portrayed a John Dixwell disturbed by nightmares of being Charles I’s executioner: ‘Forgiveness! Oh, forgiveness, and a grave!’ Dixwell’s thoughts are not restful, whether he be awake or asleep: ‘Ne’er shall I be at peace/Till in the grave’.3 It is only through helping the eponymous chief, Kerhonah, that Dixwell might find redemption for his regicidal crime.4

Other early nineteenth-century British portrayals hinted at an overenthusiastic religiosity and impulsive radicalism at odds with the British establishment of the time.5 Poet Laureate Robert Southey’s Oliver Newman, one of the earliest British imaginative portraits of Whalley and Goffe, was not wholly critical of the regicides, but it presented Goffe’s son as the judicious hero, with an impetuous and Native-threatening Goffe relegated to a bit-part. Southey first thought in 1811 of an Iliad-style epic set during King Philip’s War, and he began writing it in 1815, but Oliver Newman was never completed.6 We do know of Southey’s intentions, though, from a letter of January 1811 and an appendix to the poem in 1845, replete with references to Whalley and Goffe, their time in Hadley, and the pursuit by Edward Randolph.7 Goffe’s son, Oliver Newman, was to be a hero who buys a Native American woman and her child, Elizabeth, in order to return them to their tribe; who prioritizes this mission above his own search for his father; who tends to a wounded Mohawk; who is accused of being a spy by Native Americans, but suffers the ensuing violence with patience and fortitude; who, upon discovering his regicide father, stands by him, and even saves his enemy Edward Randolph from a murderous fate at the hands of the Native Americans. The regicide Goffe, meanwhile, was to be a hot-headed soldier who assembles some forces against the Native Americans, takes some prisoners, and is about to execute them when his son, Oliver, appears to save them. Even Goffe’s nemesis Randolph was to be portrayed in an unusually positive light, agreeing not to divulge Goffe’s whereabouts and requesting a grant of land for Oliver.

A similar reticence towards Goffe may be identified in Sir Walter Scott’s Peveril of the Peak (1822), which was written at around the same time as the composition of Southey’s Oliver Newman. Scott has Major Bridgenorth contemplating one benefit of a national calamity: some talented individuals ‘slumber’ in society’s ‘bosom’ until ‘necessity and opportunity call forth the statesman and the soldier from the shades of lowly life to the parts they are designed by Providence to perform’. Oliver Cromwell and John Milton are two names that spring to Bridgenorth’s mind. Another is the Angel of Hadley, whom Bridgenorth calls Richard Whalley, a fictional pseudonym for William Goffe. Bridgenorth relates a story from his time travelling in America, which is essentially a recapitulation of the Angel of Hadley, with a greying hero appearing to save Bridgenorth and his colonial hosts: ‘such was the influence of his appearance, his mien, his language, and his presence of mind, that he was implicitly obeyed by men who had never seen him until that moment’.8 In view of Scott’s position as a member of the conservative establishment, it is surprising that the regicide is presented in such positive and heroic terms. Or, at the very least, there is little sense of the Angel of Hadley being denounced as a criminal.9 But we might pause and question Scott’s sympathy for the regicide story when the judgement of its narrator is questioned elsewhere in the novel for being undermined by the ‘insane enthusiasm of the time’.10

Instead it is to nascent American literature that we need to turn for more overtly positive representations of Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell. By the 1840s, such was the confident enthusiasm for the regicides in America that one British visitor to New Haven was warned not to call them ‘regicides’ at all—the term implied criminality—but ‘the judges’.11 Regicides had appeared in American novels with such frequency in the 1820s and 1830s that it was not uncommon to write a novel with a cameo appearance, even if that cameo was sometimes rather forced. One reviewer of John C. McCall’s Witch of New England (1824), for example, was puzzled by Whalley’s presence since the author did ‘nothing with him, except to kill him in defiance of physiology, representing him as being found dead, with his body erect, intent on his book, and looking as if he were alive’.12 As the English regicides became a dominant feature of nineteenth-century American literature, historical fiction and historical fact existed in a symbiotic state. Each had a productive effect upon the other: research on the regicides prompted fictional portraits of them; fictional portraits invigorated interest in what really happened; and the real historical story encouraged even more creative literary accounts. In the process, the regicide myths from the eighteenth century were perpetuated, or new ones were founded.

American history is replete with myths, especially those surrounding American independence; they have been a binding force, helping to create a unifying American national identity. It has been argued that the demands of patriotism, the desire for good stories, and the longing for a collective identity have all combined to produce mythological stories centred on opposites: heroes and villains, wit and foolery, good and evil, David and Goliath. Cast in the forge of nineteenth-century Romanticism, these myths arguably subverted the democratic and communitarian impulses of the American revolutionaries and compressed the Revolution’s story and ideals into those of comic-book superheroes. These characters, almost always military, were found in isolated stories, with neat beginnings and ends, to provide appropriate moral instruction to successive American generations.13 This style of writing was, in part, a reaction to the bloody realities of the Revolutionary War. Those who had lived through it, and their immediate descendants, concealed the miseries of warfare; their descendants then devised white-washed stories with carefully selected plots that were suitable for patriotic public consumption. The Romantics were fortunate to find in the regicides a tale that could be portrayed as ‘clean’ and capable of celebrating the revolutionary values of the 1770s, while transplanting them into sanitized stories much less harrowing than the warfare that had been witnessed only too recently.

Furthermore, in the half-century after the American Revolution, when the new American nation was being forged, a new national identity needed to be forged alongside it. America was an adolescent nation with disparate threats to that national identity. As its territory expanded westward, there was the danger that unifying national bonds might be loosened, and that those more interested in focusing on the distinctiveness of their local region might undermine a cohesive American character.14 A significant part of America’s new national identity consisted of its history, not least that of its founders, some of which needed to be recalibrated and mythologized to underline the idea that America’s possession of independence and liberty was inevitable and timeless.15 Literature became a key vehicle for the creation of a distinctive, independent, cultural identity, especially once the War of 1812 provoked a further surge of American nationalism.16 American authors who imitated European writers were accused of ‘denationalizing the American mind’ and of ‘enslaving the national heart’.17 Instead, American history was to feature in American literature to highlight a proud, distinctive, separate nation and to entertain, inspire, and educate readers in desirable habits, tastes, and principles. Episodes from American history were to be selected that would instruct readers in ‘great moral truths’; and the most prominent episodes were to be stories about adventure and freedom in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century America.18

There were few stories from the colonial period that combined adventure and freedom more entertainingly than those of regicides on the run in America. But there were tensions here: the colonial history that nationalistic American authors were meant to adopt could not avoid including a significant European element. Europeans, who were crossing the Atlantic and settling in America throughout the colonial period, did not sever their links completely with the Old World. Moreover, despite this call for American cultural independence and superiority, there was still a residual Anglophilia. As Orestes Brownson observed in 1839, England still ‘continued to manufacture our cottons and woollens, our knives and forks, our fashions, our literature, our sentiments and opinions’.19 In the case of the regicides in America, these became creative tensions: the Anglophiles could read about Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell, and remember the regicides were English, but enjoy the fact they were not subject to the morally and politically inferior governance represented by English kings. The advocates of American cultural independence and superiority could adopt the regicides as honorary proto-American revolutionaries, protected by colonial authorities who embodied the values of the American Revolution more than they did the political culture of Restoration England. Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell were un-English in the sense that they were not welcome in their native land after the Restoration of the monarchy and had no sympathy with the values promoted by Charles II and his supporters. It mattered little that, in reality, Goffe admitted he always felt a stranger in America. More important was the incorporation of the regicides into an early republican, nationalistic, American literary framework.

The spirit(s) of the regicides

The regicides were associated with several Romantic characteristics that made them attractive to early nineteenth-century American authors: a sense of history, nationalism, liberty, individual bravery, and—the one that first reached prominence—the supernatural.20 The Puritan obsession with the activity of God and the Antichrist on earth underlaid a preoccupation with Satan’s influence among early Americans. This fixation led to the most famous of the witch trials at Salem in 1692 that, in turn, perpetuated interest in the presence of the Devil and his agents in the New World. It was impossible to look back to seventeenth-century America without thinking of the witchcraze; thus many early American novels, set in the colonial period, featured the supernatural. The story of the regicides in America neatly dovetailed with this literary interest in the paranormal as Whalley and Goffe, like spectres, appeared and disappeared from view. The regicides and their protectors adopted a mode of disguise that was plausible to their superstitious contemporaries; they could appear and move about small parochial communities in supernatural guises. The Angel of Hadley, in particular, was a ghostly figure that provided a useful spectral metaphor for liberty for those penning novels about the regicides.

James McHenry’s The Spectre of the Forest (1823), for example, presents Goffe as a tall, slender figure aiding his adopted community in moments of peril. To provide security ‘from the grasp of the law’, Goffe is ‘obliged to assume the character of a supernatural being’. His appearance is made all the more mysterious by his apparel. Wearing surplice-like garments of black fur with a black hood, he carries a bible in one hand and a white staff in the other. He appears to New Englanders to assure them: ‘a servant of God will meet you, and from him you will learn that the Redeemer of Israel is mighty to save you’. McHenry’s Goffe survives into the 1690s, when King William and Queen Mary pardon him. Mary declares that Goffe ‘must have suffered much amidst those savage deserts . . . his old age might, without any injury to the cause of royalty, or any appearance of disrespect to our grandfather’s memory, be allowed to enjoy peace in that remote country, where he has been so long concealed’. William agrees in a cod-Dutch accent, so long as he receives confirmation that Goffe is not an enemy to their monarchical government.21

A similar ghostly and heroic figure appears in J.N. Barker’s play The Tragedy of Superstition (1826). Sir Reginald Egerton—a clear fictional representation of Edward Randolph—is sent by Charles II to find the regicides, because the king ‘finds it decorous to grow a little angry with the persons that killed his father’ and has heard that the people of New England have been giving the fugitives ‘food and shelter’. Goffe, who is known only as the ‘Unknown’, appears at times of danger, like McHenry’s spectre, to protect the people of New England. Barker makes the Unknown appear like the Angel of Hadley to coordinate the defence of his adopted town against the Native Americans: ‘Turn back for shame . . . I am sent to save you’, he implores.22

Goffe appears in a comparable fashion in James Fenimore Cooper’s The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish (1829), but this time he is called ‘Submission’, which Cooper claimed ‘savoured of the religious enthusiasm of the times’, and which denoted the regicide’s readiness to submit to God’s providential design. In a nod to the Angel of Hadley, Submission remains unmoved by the threat from Native Americans, insisting that ‘peril and I are no strangers’. He is central to the defence of Wish-ton-Wish during a number of attacks and is cast as a vigorous military hero: ‘he parried, at some jeopardy to one hand, a thrust aimed at his throat, while with the other he seized the warrior who had inflicted the blow, and . . . buried his own keen blade to its haft in the body’. In a later attack Submission disregards his own safety to call the colonists to their square and urges them to ‘be firm’; he struggles ‘manfully’ against his ‘luckless fortune’.23 As a novel, The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish was not much of a success,24 but as a play it enjoyed more positive fortunes. Goffe became one of the most prominent stage characters in nineteenth-century America. In its theatrical form, The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish was described as a ‘burletta’, a musical drama akin to comic opera, and, for much of its stage-life, it featured the famous French ballet-dancer Celine Celeste. It opened in London in November 1831, toured America at the height of its popularity in the 1830s to 1850s, and was still in production on both sides of the Atlantic until at least 1878.

In Delia Salter Bacon’s Tales of the Puritans: The Regicides (1831), it is not Goffe who appears as a spectral vision but his wife, who is also Whalley’s daughter. Moving the supernatural lens away from Hadley, Bacon focuses instead on the Royalist agents Kellond and Kirke, who arrive in New Haven in search of the regicides and then meet with William Leete. A fictional character, Samuel, is sent from Leete’s household to warn Whalley and Goffe of the agents’ presence in New Haven. The regicides retire to the cave at West Rock and tales are spread of a supernatural ‘beautiful being’ living in the cave—‘strange sights and unearthly voices had been seen and heard at midnight’—to ensure that no one visits it and discovers them. This ‘beautiful being’, known as the Lady of the Mist, is none other than Isabella Goffe. As Kellond and Kirke get closer to their quarry, a pessimistic William Goffe concedes to Isabella that their time on the run has come to an end; that they will be caught and must face the inevitable penalty of death. Nonetheless, Whalley and Goffe leave the cave at West Rock, just moments before Kellond and Kirke arrive. Following the gaze of Isabella, who is watching her father and husband leave, Kellond and Kirke pursue the regicides down the hill, only to be tricked by the fugitives, who hide under a footbridge (the neck bridge from Stiles’s History). Whalley later dies in his bed, wrapped in the ‘peaceful beauty of holiness’, while Bacon’s Goffe is free to re-appear in New Haven as Walter Goldsmith, a benevolent yet reserved gentleman, lately arrived from England.25

Four years after the publication of Bacon’s Regicides, a new generation of Americans was introduced to Stiles’s History, with its coverage of the Angel of Hadley, thanks to its inclusion in S.L. Knapp’s Library of American History (1835). This came in the wake of William Leete Stone’s—note his name—Mercy Disborough (1834) in which supernatural happenings had once again been portrayed keeping people away from the regicides. In this novel, stories circulate of low sounds and voices and shards of light appearing and disappearing in an isolated storehouse owned by William Leete. The voices belong to Whalley and Goffe but no one dares approach the storehouse for fear of encountering paranormal beings. Whenever the inhabitants of New Haven mention the rumours to Leete, he shakes his head and cautions them ‘not to throw themselves within the charmed circle of Azazel, by approaching too near’. As the story progresses and tales of unnatural occurrences spread around the New Haven community, claims about the storehouse become even more exaggerated. Demons are described howling ‘pitifully in the night . . . causing blue flames and sudden flashes of light to issue from the crevices in the walls’. Towards the conclusion of Mercy Disborough, the author introduces some false history by imagining that in the mid-eighteenth century the ‘haunted’ storehouse was razed and an inscription on the stone walls discovered:

Stranger, if thou art a friend to unpolluted liberty, look upon the names of two of its humble and constant, but unfortunate defenders, who, having assisted in openly and fairly adjudging a tyrant to death, were afterwards compelled, like Lot, to flee to the caves and the mountains of this howling wilderness, to escape the vengeance of the tyrant’s son. But, even in these distant ends of the earth, the Philistines were upon them, and they must have perished but for the kindness of the governor, who put his life in his hand, and cherished them for many months in this dreary abode.

EDWARD WHALLEY. WILLIAM GOFFE

Opposition to tyrants, is obedience to God.26

Bacon’s—and Whalley’s?—rebellion

William Leete Stone had been inspired by the actual text inscribed on the Judges Cave by Isaac Jones in 1803. Indeed, aside from the combination of the regicides and the supernatural, the dominant theme that emerged from nineteenth-century portraits of Whalley and Goffe, in history books, novels, and plays, was the association between the regicides and liberty. Leonard Bacon, for example, declared that he knew of no other example from history that exhibited ‘a more admirable combination of courage and adroitness, of fidelity to friendship, of magnanimity in distress, and of the fearless yet discreet assertion of great principles of liberty’.27 Bacon wrote a preface for Israel Warren’s full-length history of the regicides, in which Warren hoped that ‘our young readers will find in the narrative a source of instruction in the principles of civil and religious liberty’.28

In W.A. Caruthers’s The Cavaliers of Virginia (1834–5), indeed, the English revolutionary becomes the American proto-revolutionary. Because Whalley represents liberty, Caruthers places him—now called ‘the Recluse’—in mid-1670s Virginia so he can be associated with the rebellion led by Nathaniel Bacon. The traditional view is that Bacon’s Rebellion, an armed insurrection by Virginian settlers against Governor William Berkeley, was a precursor to the American Revolution because it involved a challenge to the authority of the colonial governor exactly one hundred years before the Declaration of Independence. While, in reality, Whalley had died by 1676, Caruthers includes him in The Cavaliers of Virginia and initially portrays him in sympathetic terms, with an admirable military bearing and stoic suffering in the face of exile and ignominy. He is described as having ‘weatherbeaten’ features, but he is ‘eminently handsome’; he is ‘perfectly proportioned’, with a presence that is ‘intellectual and commanding in the highest degree’. His cave outside Jamestown, a loose rendering of the real Judges Cave in New Haven, leads to a glittering arsenal that the Recluse has collected to aid the forces of liberty. The Recluse has kept a diary of the previous three decades, with 30 January 1649 bereft of text; only a bloodied handprint records the events of that day.29

The Recluse appears in The Cavaliers of Virginia whenever the young Nathaniel Bacon requires assistance, and Bacon’s struggles are cast in terms of a fight for liberty against tyranny: either from nearby Native Americans or the encroaching excesses of European aristocracy as represented by Governor Berkeley. There are some complications: Bacon himself is not fully a Roundhead heir, descended as he is from both Royalist and Parliamentarian stock. Then, having discovered the death of his own fictional son, the Recluse is presented as repenting at length about his actions in the English civil wars and regicide, actions that had caused his lengthy exile: ‘Retributive justice pursues and overtakes the guilty to the ends of the earth . . . Oh God, how just and appropriate are thy punishments!’30 Caruthers’s worn-down regicide may seem repentant, but the author presents the rebellion the Recluse supports as worthy of celebration: ‘Here was sown the first germ of the American Revolution . . . Exactly one hundred years before the American Revolution, there was a Virginia revolution based upon precisely similar principles. The struggle commenced between the representatives of the people and the representatives of the king’.31

Despite the chronological and centennial convenience, the reality was more complex than this apparently straightforward rehearsal of American liberty versus British colonial tyranny.32 Even before Nathaniel Bacon had arrived in America, tension had been increasing in Virginia. As the farming and sale of tobacco reaped massive profits, English colonists appropriated land in Virginia already occupied by Native Americans. By the end of the 1660s, around 10 million pounds of tobacco was being produced per year. Tobacco plantations took over more and more land occupied by Native Americans, who responded by destroying plantations and murdering settlers. The typical settler, too, exacerbated the tension felt in Virginia: they tended to be independent, competitive, and ruthless since tobacco plantations were tough to run, were thousands of miles away from England, and were situated in a harsh environment where death could strike suddenly through disease or murder. Men struggled to survive in these rough conditions and those who did were tough—they had to be: society was male-centred and unstable; life expectancy was short; the work was very hard; and they had guns.

Charles I appointed William Berkeley governor of Virginia in 1641. For fifteen years he ensured that Virginia’s administrators were his supporters and friends. He imposed heavy taxes on tobacco growers, in part to pay his generous salary of £1,000 per year, and gave the best land to his friends. Many men who had left England for Virginia had done so because they hoped to own land and gain great wealth; Berkeley was thwarting this ambition. Furthermore, there was a rumour that Berkeley would tax settlers 1,000 pounds of tobacco to pay for forts and troops against the Native population. By 1665, the tension had increased still further as vast quantities of tobacco were being produced which flooded the market in England and caused prices to fall. Incomes in Virginia declined and taxes were heavy. To make matters worse, England was at war with the Dutch in 1665–7 and 1672–4; so the Dutch destroyed English tobacco ships.

At this point, Nathaniel Bacon, an inflammatory character, appeared in this potentially explosive situation. Bacon was the son of a Suffolk gentleman and a cousin of Governor Berkeley. He had been expelled from the University of Cambridge for ‘extravagancies’ and had been involved in a fraud-scheme; so his father sent him to America to join the hundreds of other ambitious and frustrated young settlers with questionable past lives. Bacon gained over 1,000 acres of land in Virginia, close to some Native Americans. Settlers like Bacon, in pursuit of more land to grow tobacco, were frequently aggressive towards these neighbours. But they encountered opposition from Governor Berkeley who punished them for such aggression.

In August 1675 Nathaniel Bacon took prisoner some Appomattox Native Americans for, he claimed, stealing corn. Berkeley criticized Bacon publicly for this rash action, because it would strain relations between Native Americans and English settlers even further. Then, in September, a thousand settlers surrounded Native American forts to punish them for their alleged behaviour the previous month. Native American chiefs were led away and murdered; some managed to escape, however, and ten settlers were killed. The following summer, when poor weather ruined the tobacco crops, some settlers blamed this misfortune on the ‘sorceries of the Indians’. In June 1676, therefore, 400 men on foot, and 120 on horseback, marched with Nathaniel Bacon to Jamestown. Bacon demanded that Governor Berkeley make him general ‘of all the forces in Virginia against the Indians’. Berkeley refused, stormed out of his house to meet Bacon, bared his chest, and shouted ‘Here! Shoot me, foregod, fair mark, shoot!’ Bacon set fire to Jamestown, but four months later died from dysentery. One thousand government troops made sure that the rebellion was put down. None of this had anything to do with Edward Whalley, who by 1676 was almost certainly dead. But historical accuracy was not allowed to impede imaginative representations of American history, like that offered by Caruthers, which looked back over a hundred years before the Revolution to identify struggles for liberty which, in turn, looked forward to the outbreak of the American War of Independence.

The regicides and liberty

The majority of nineteenth-century authors inspired by the regicides placed Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell on this continuum of American liberty, but a few demurred. George Bancroft, in his six-volume history of America, wrote tersely and cryptically that Goffe was ‘a good soldier, but ignorant of the true principles of freedom’.33 Bancroft did not expound the precise nature of these ‘true’ principles or the precise flaws in Goffe’s character that led him to fall short in his appreciation of them, but he was being consistent in his distinction between celebrating the American Revolution while deriding rebellion. Bancroft saw the American Revolution as a providential step in mankind’s divinely ordained, organic path towards perfection; upstart rebels like Goffe were primal, explosive, and destructive.34

Barker’s Tragedy of Superstition followed the interpretation of the regicides that had been favoured by Thomas Hutchinson and Peter Oliver in the eighteenth century: that Goffe was a lonely criminal with very few political sympathizers.35 Then, three years later, J.A. Stone’s Metamora (1829) displayed a similar restraint towards the regicides. Stone provides the familiar figure of a regicide, Mordaunt (or Hammond of Harrington—an echo of the seventeenth-century English republican James Harrington), evading Charles II’s agents by hiding in burrows. Mordaunt, however, is not the heroic figure provided by the likes of McHenry. Instead, he is a character who tries to force his daughter into a socially advantageous marriage and who dies at the hands of the courageous Metamora rather than being a heroic saviour like the Angel of Hadley. Moreover, Mordaunt’s role in the execution of Charles I actually foments the attempted overthrow of tyrannical Puritan governance in King Philip’s War; he is a cause of the Hadley-style attack, not a valiant solution.36

While his character represented an unusual portrayal of a regicide in America, Mordaunt was one of the most prominent regicides on the nineteenth-century American stage. Metamora, like the stage version of Fenimore Cooper’s Wept, became very popular, especially in the 1830s and 1840s, and, in fact, outlasted Wept, with performances until at least 1887: ‘lines from the play became household words, “as familiar upon the public’s tongue as the name of Washington” ’.37 Stone had subverted the popular view that an English regicide had thwarted the threat of tyranny posed by Native Americans in King Philip’s War, and had thus preserved the lives and liberties of the colonists.

But these sceptical authors were in the minority. As with Caruthers’s Cavaliers of Virginia, a frequent literary presence at moments of crisis was an English regicide. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘The Gray Champion’ (1835), for example, focuses on the reign of James II and the administration of Sir Edmund Andros, ‘governor of the Dominion of New England’ between 1686 and 1689.38 The governor of New England that Leete had feared so much in 1661 had been imposed by 1686, and Hawthorne notes that Andros’s administration ‘lacked scarcely a single characteristic of tyranny’, as it undermined the freedom of the colonies of New England. There is great excitement, then, in Hawthorne’s tale, when rumours spread that William of Orange is preparing to overthrow James II, the king who had sent Andros to New England.

In response, Andros and his councillors—including Edward Randolph—attempt a show of strength, appearing on the streets of Boston along with the high churchmen and the red-coated governor’s guard. A crowd appears on King Street made up of veterans from King Philip’s War and, indeed, some old Parliamentarians. As reports spread that Andros is going to order a massacre of the Bostonians, a voice cries from the crowd, ‘Oh! Lord of Hosts . . . provide a champion for thy people’. At this point the figure of an old, grey-bearded Puritan appears, wearing a dark cloak, and carrying a sword and staff. He walks alone along the middle of the street to confront Andros’s assembled soldiers. As the old man advances, the soldiers’ drumming intensifies, until he ends up marching in step to the beat. He stops sixty feet from Andros and his companions, holds out his staff, and shouts, ‘Stand!’ The drumming ceases, the old man stares at Andros, and the soldiers stop their advance, despite Randolph’s cries for them to continue. The old Puritan addresses Andros: ‘I have staid the march of a king himself, ere now . . . I am here because the cry of an oppressed people hath disturbed me in my secret place’. He adds that James II has been deposed and Andros’s governorship has ceased. Andros stares at the old man but orders a retreat before the ‘Gray Champion’ disappears.

The old man is, of course, William Goffe, and he appears to save the colonists from tyranny in Boston, in much the same way that his ‘Angel’ had appeared to save them from a different kind of tyranny in Hadley. That the real Goffe was long dead by 1689 was irrelevant. The regicide figure appears, says Hawthorne, ‘whenever the descendants of the Puritans are to show the spirit of their sires’. So, he is present on King Street at the Boston Massacre in 1770, then five years later as the first revolutionaries fall at Lexington, then at Bunker Hill. The English regicide embodies America’s revolutionary spirit and appears whenever there is the threat of oppression by tyranny, either from America’s own rulers or from an external enemy. As Hawthorne puts it, the regicide ‘is the type of New-England’s hereditary spirit . . . New-England’s sons will vindicate their ancestry’. Indeed, Hawthorne’s account was one of the first to depict the regicides as explicit representatives of the values of the American Revolution long before the Revolution had occurred.

This idea was adopted seven years after Hawthorne’s ‘Gray Champion’, by the anonymous author of The Salem Belle (1842). In this novel, too, the writer considered the link between the seventeenth-century Puritans and their eighteenth-century descendants: ‘The fathers of those times sleep in the dust. The sons, too, are silent as the fathers; but on the ears of the third generation the hymn of liberty poured its strains of gladness, and the name of Washington was borne on every breeze and enshrined in every patriot’s heart’. The ‘tyrant’ against whom these seventeenth-century Puritans were fighting was not Washington’s George III, but Charles II. While The Salem Belle does not include a regicide as a central character, a journey through Hadley provides an opportunity for meditation on ‘the venerated Gen. Goffe’, who was ‘loved’ by the whole town which protected him from ‘the tyrannical Charles [II]’. Somewhat intriguingly, the author expresses compassion for Charles I, ‘the only Stuart who commands the sympathy and affection of posterity’, but, even if Goffe’s regicidal actions had been ‘misguided’, his name was held in Hadley ‘in honored and grateful remembrance’. For it was individuals like Goffe who led the way for America to become a country ‘where no kingly prerogative tramples with its iron foot on the sacred rights of man’.39

H.W. Herbert’s Ruth Whalley (1845) takes a different approach to the regicides’ fight against tyranny. As with McHenry’s Spectre, Ruth Whalley has a regicide surviving long into the 1680s. As with Hawthorne’s ‘Gray Champion’, it has a proto-republican Massachusetts Bay suffering under the tyranny of Edmund Andros. This regicide, though, is not William Goffe, but an octogenarian Edward Whalley. He sits erect yet mute in the corner of a house owned by his son, Merciful Whalley. He never smiles or takes any notice of events going on around him. He does not stir until his son is struck by a Native American girl, Tituba, and Merciful attacks her in return. Ruth Whalley screams at her father, Merciful, to stop his violence, fearing that he will murder Tituba. Edward Whalley grabs a steel-hilted sword, and rushes towards his son. Edward Whalley thinks, however, that he is back in the English civil war, that the screams come from his wife, and that Charles I’s Cavaliers are attacking her. Edward rebukes Merciful for attacking the girl and for being a ‘persecutor’. On the national stage or in the domestic setting, Edward Whalley upholds liberty against tyranny, whether that tyranny originates from the Stuarts and their colonial officers or from his own violent son.40

Republican enthusiasm was taken a step further by J.K. Paulding in The Puritan and His Daughter (1849). Subverting the tradition of dedicating books to monarchs, Paulding instead dedicated his novel to ‘the most high and mighty sovereign of sovereigns, King People’. He hoped that generations would be taught the lessons illustrated in the book, ‘insomuch that it shall go through as many editions as the Pilgrim’s Progress or Robinson Crusoe: that all members of Congress, past, present, and future, shall be furnished with a copy’. Paulding’s central character, Harold Habingdon, flees England at the Restoration and later encounters an old, white-haired man whom he has not seen since the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644. This regicide informs Habingdon that he has ‘been hunted like a wild beast’ and forced to hide in various locations. The two contemplate Charles I’s claims to martyrdom and agree that an earthly tribunal rightly condemned the king for abusing his power and oppressing his people. The grey-haired man hopes that the New World will do justice to the regicides’ memory, for it is here that there are ‘no impregnable bulwarks of oppression . . . no bristling bayonets pointed at the heart, to quell the throbbings of liberty’.41

For Paulding, there was something innate in America that made it a crucible for freedom. He envisaged a blank social and political slate on which a new administration and polity, based on liberty, could be drawn. The first letters had been etched by individuals like the English regicides, who had insisted that they—not God—would judge Charles I, before transplanting these ideas of liberty to the New World after they had been undermined in the Old. But there is an important caveat to add here: by tracing the origins of American liberty back to the age of the Puritan settlers, far before 1776, American authors could celebrate that liberty without celebrating the mob-led, demagogical, anarchic excesses that many observers saw resulting from the American Revolution.42 In some interpretations, this ‘harvest of Puritanism’ had within it revolutionaries like Whalley and Goffe, who themselves now represented American Puritanism in its foundation of a wise, patient, stoic, respectable revolution, instead of the English Puritanism that had been explosive and bloody—even if, in reality, their signing of the king’s death warrant in 1649 had, temporarily at least, helped turn the world upside down.

Writing Randolph

Some authors were preoccupied with individuals from this Old World who were on the regicides’ tails, and who represented a new generation of Stuart oppression that was attempting to quash the republican ideals embodied by Whalley and Goffe. One such prominent individual was Edward Randolph. As Nathaniel Hawthorne had done in ‘The Gray Champion’, G.H. Hollister presented Randolph in a very negative fashion in Mount Hope (1851). Randolph, years after he pursued the regicides, had become a bête noire in America. Charles II, with Randolph’s encouragement, had revoked Massachusetts Bay’s charter in 1684; then Randolph had been a prominent member of Edmund Andros’s administration of the Dominion of New England. It is unsurprising, therefore, that authors like Hawthorne and Hollister should have cast Randolph’s earlier anti-regicide behaviour in a similar critical light. Randolph is described as ‘a vampire in human shape’ and a ‘name so associated with tyranny and overreaching power in the mind of every colonist’.43

While Mount Hope includes the standard appearance of the Angel of Hadley, Hollister reserves the greater action for fictional face-to-face conflict between Randolph and the regicides. On one occasion, Goffe ascends a rock platform just above Randolph, who shoots his rifle directly at the regicide’s chest. The shot misses, and as Randolph storms towards Goffe for hand-to-hand combat, Randolph—distracted by ‘the glittering spurs of knighthood and the visions of a successful political career’—is stabbed in his side. Even more dramatically and improbably, the denouement of Mount Hope has Hollister imagining many of the principal actors in the regicides’ story assembling for one final skirmish. John Dixwell arrives to inform Goffe that Randolph is still on their tail. Channelling his inner Hamlet, Randolph appears, announcing that the regicides are ‘dead—for a ducat!’ before crossing swords with Goffe. Dixwell starts shooting. A young man named William Ashford bursts in to fight Randolph. Kellond and Kirke, of all people, turn up to attack Goffe, but without success. Kellond is killed; Kirke begs for mercy. Ashford wounds Randolph, but not mortally, so Randolph is able to escape to England.44

In Hollister’s Mount Hope, William Ashford is actually William Goffe Jr, who is reunited with his father after a period of estrangement and the younger man’s journey through America, meeting Dixwell, Winthrop, and Russell en route. Indeed, it was common for pro-regicide novelists to give Whalley and Goffe their own children based in America. In J.R. Musick’s A Century Too Soon (1893), Goffe’s daughter is betrothed to Robert Stevens, one of Bacon’s ‘republican’ rebels: Robert’s ‘meeting with General Goffe and his love for Ester had more strongly cemented his love for liberty’.45 Goffe has a daughter, Maria, in Grimm’s The King’s Judges (1892), while in McHenry’s Spectre of the Forest, Goffe is the father of Ester Devenart. Edward Whalley, too, has a son, Merciful, in Herbert’s Ruth Whalley, as well as his eponymous granddaughter. In fictional terms, therefore, the regicides are imagined as bestowing a biological legacy: revolutionary names and revolutionary genes that form a direct genealogical link between 1649 and 1776. The regicides’ revolutionary spirit did not merely live on in some intangible and undetectable form until its re-emergence during the War of Independence. Instead, pro-regicide authors portrayed them as proto-Founding Fathers who not only transplanted revolutionary ideas to America in the 1660s but also provided the American descendants in whom those ideas would germinate a century later.

Beyond fiction

Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell did not just appear in novels in the nineteenth century. In Britain, the incendiary British socialist George Julian Harney invoked John Dixwell in his periodical The Democratic Review (1849–50). Harney had been imprisoned for selling the unstamped Poor Man’s Guardian; he was a founder of the republican East London Democratic Association; he was a Chartist who urged the use of physical force to achieve universal suffrage; he was an advocate of a General Strike; he met Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels; and his journal, The Red Republican, published the first translation of The Communist Manifesto. Harney’s Democratic Review carried an article prompted by the opening of Dixwell’s grave in New Haven and the erection of a monument to the regicide. Dixwell had died in New Haven on 18 March 1689 and his remains had been deposited in a grave on (or before) 1 April. The Democratic Review hailed Dixwell as one of those who had acted as a ‘champion’ of the Good Old Cause in the ‘revolutionary conflict’ and who had been confident to his dying day that ‘the Lord will appear for his people . . . and that there will be those in power again who will relieve the injured and oppressed’.46 Writers in America had no need to foment revolution in the same way as George Julian Harney: they had already shaken off the shackles of British rule and few would have followed Harney down the path of revolutionary socialism.

In 1850 John and Elizabeth Barber considered the story of Whalley and Goffe hiding in a cave to be of use for ‘moral and religious’ instruction. Citing the inscription on the cave, ‘Opposition to tyrants is obedience to God’, they published a poem that would educate their readers about the regicides’ plight. The poem compared the regicides to the ‘holy men of old’, struggling against the elements to preserve their liberty and their opposition to tyranny.47 Much more famously, Henry David Thoreau, while contemplating ‘solitude’ in his Walden (1854), referred to ‘a most wise and humorous friend . . . who keeps himself more secret than ever did Goffe or Whalley’;48 while Walt Whitman, in the 1860s, published the section of Leaves of Grass titled ‘To a Cantatrice’:

Here, take this gift,

I was reserving it for some hero, speaker, or general,

One who should serve the good old cause, the great idea, the progress and

freedom of the race,

Some brave confronter of despots, some daring rebel;

But I see that what I was reserving belongs to you just as much as to any.49

Whitman’s phrase ‘good old cause’ referred generically to the cause of freedom and liberty, and he used it elsewhere in the context of America’s civil war. But the phrase was borrowed from the English civil war and Interregnum, and it would have been difficult by this point to read about a ‘general’ serving the ‘good old cause’, a ‘brave confronter of despots’, without thinking back to those ‘daring rebels’ Whalley and Goffe.50

Celebration of republican freedom was also to be found in American visual art of the mid-nineteenth century. On 24 December 1847, Prosper Wetmore, president of the American Art Union, addressed that society and refuted the assumption that republican institutions were inimical to ‘the cultivation of the arts of design’; that the ‘influences of a free public opinion must of necessity be indicated in something “savage and wild” ’. Instead, the artwork commissioned or encouraged by the American Art Union, the artefacts of the American School, sent out ‘a living school of moral beauty’, a ‘contemplation of the sublime, the beautiful, the true’. One of these paintings, distributed among the union’s members in December 1847, was Thomas P. Rossiter’s The Regicide Judges Succored by the Ladies of New Haven (see Figure 7).51 Rossiter was a New Haven native and the catalogue of his paintings notes that The Regicide Judges was painted in 1847 and owned by a member of the banking, real estate, legal, and railroad Litchfield family.52

As with the recent American literature on Whalley and Goffe, Rossiter’s painting was a sanitized portrayal of the regicides, and one that amended their story so it could fit the style of American national identity encouraged at the time. He may have promoted Wetmore’s ‘moral beauty’, but not really ‘contemplation of . . . the true’. Rossiter’s painting has the elder of the regicides, Whalley, standing well dressed, poised, and dignified in front of a large opening to the Judges Cave, in contrast to the reality of a cramped and undignified existence at the mercy of the elements. To the right of the composition sit Goffe and another male figure, presumably Richard Sperry, who had assisted the regicides during their time on West Rock. To the left of the painting are four female figures, those ‘Ladies of New Haven’ who were offering ‘succor’ to Whalley and Goffe. This was in contrast to the documentary evidence of the regicides’ time in the cave, but it enabled Rossiter to place the scene of the Judges Cave more firmly in the context of artwork that promoted American national identity through celebration of its colonial past, shifting the focus away from the English regicides and towards the American colonists. Whalley may stand at the centre of the composition, but the muse-like ladies of New Haven are the heroic protectors in a sturdy yet serene American landscape. The importance Rossiter ascribed to the Judges Cave can be gleaned from the other, now much more famous, iconic historical figures he incorporated into his oeuvre: Christopher Columbus; the Mayflower pilgrims; the signatories of the American constitution; and paintings of George Washington in various settings.53

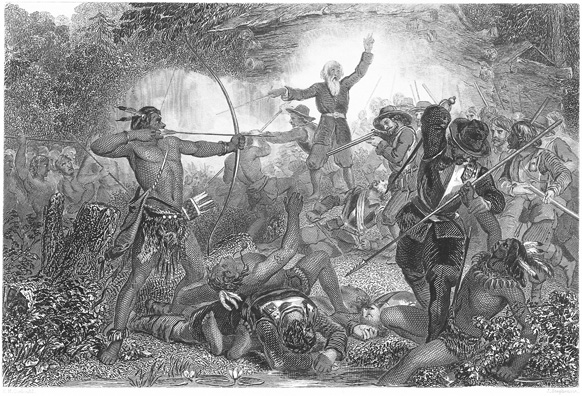

Approximately two years after Rossiter painted The Regicide Judges, a regicide took a more dramatic role in what has become the iconic canvas associated with the regicides in America. F.A. Chapman’s The Perils of Our Forefathers is an intense and theatrical portrayal of Goffe’s appearance as the Angel of Hadley (see Figure 8). Chapman, first president of the Brooklyn Art School and leading spirit in its foundation, had been born in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, thirty miles east of New Haven and ninety miles south of Hadley. He was interested in the history of his native region and claimed descent from Puritan colonists of the area. The Perils of Our Forefathers portrays these Puritans cowering in the Hadley church, with Reverend John Russell in his pulpit looking at first resigned, but on closer inspection taking hold of a gun. Through the church doors we glimpse a chaotic scene outside, with houses on fire, colonists panicking, and Native Americans about to storm the colonists’ safe haven. But in the centre of the composition stands William Goffe: aged and hoary yet upright and determined, fearlessly coordinating Hadley’s defence. From 1859 J.C. McRae greatly expanded the audience for Chapman’s dramatic rendering of the Angel of Hadley story by making engravings that were very popular and sold widely.54 A similar engraving, E.H. Corbauld’s Goffe Repulsing the Indians, had already been in circulation, though in this rendering the inhabitants of Hadley are mid-battle, with Native Americans drawing their bows and arrows in the foreground, and a more cartoon-like Goffe stands in the centre of the action with sword drawn and his left hand in the air directing the colonists’ resistance (see Figure 9).

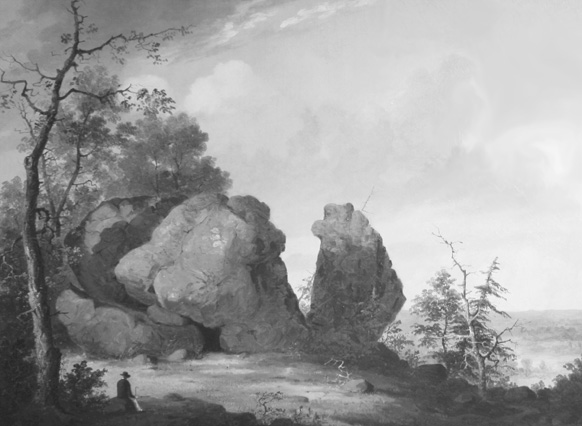

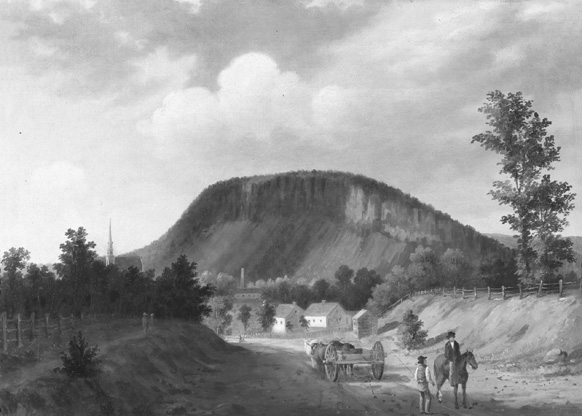

The 1850s also witnessed G.H. Durrie’s contributions to the visual culture of the regicides with his paintings of West Rock (1853) and Judges Cave (1856) (see Figures 10 and 11). As with Frederic Edwin Church’s West Rock, New Haven (1849), Durrie’s paintings did not feature a visual representation of the regicides themselves, but they did combine two related interests. The first was the beautiful and dramatic territory of New Haven, the portrayal of which on canvas promoted the rugged and peaceful American landscape, a contribution to a distinctive American national identity through the visual arts. The second was the ghost of the regicides: they did not need to be physically present on canvas for the viewer to make their connection between the New Haven landscape and the dramatic story of the escape of Whalley and Goffe. The very name, Judges Cave, evoked their plight when looking at the iconic New Haven scene. The empty cave was almost biblical in its dramatic emptiness: a timeless and immovable symbol of liberty against tyranny, with the spirit of Whalley and Goffe living on there, even when their physical bodies were gone. By America’s own civil war, then, heroes from England’s civil war were prominent features on page, stage, and canvas. They were real or spectral figures who were modified to entertain, to educate, and to celebrate within a nascent American national identity that had to find ways to come to terms with its European origins.