1 THE SHAKER STYLE

The Creative Process

The creative process does not take place in a vacuum. Certain remembrances are at play when a craftsman designs a piece of furniture, a certain vocabulary is used in producing the form. The language he speaks, all those three-dimensional designs he has lived in, on, or near, indeed his whole past and present, are the wellsprings of his creativity. It was Tennyson’s Ulysses who said, “I am part of all that I have seen, and all I have seen is a part of me.” In a sense, it can be argued that there is no such thing as pure creativity, that at best we can recreate with a slight improvement here or there. Design is synthesis, the reordering of existing parts into a new whole. This process is universal. The Egyptian craftsman of funeral boxes, the unknown Renaissance cabinetmaker, Thomas Jefferson in laying out the University of Virginia-all were synthesizers who borrowed images from their surroundings and produced forms of utility and joy.

As a designer and builder of furniture I see myself as a synthesizer. The drawings and photographs contained herein represent a blending of antique Shaker forms and contemporary forms. None of these are totally original designs, nor are they copies. I guess we are safe in saying that they are a composite, a synthesis, of the best of a number of worlds.

If we approach the study of Shaker furniture with this as a fundamental premise, a needed objectivity is attained. To understand Shaker design one must understand what the Shakers were and what their man-made visual world consisted of.

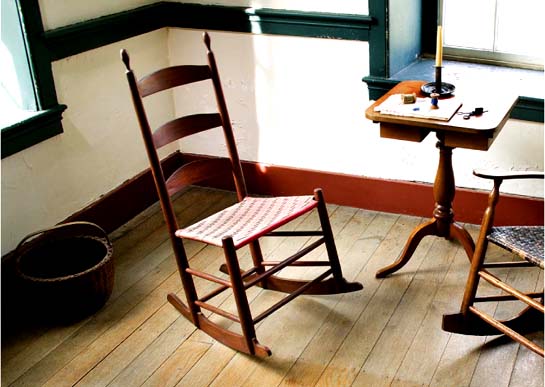

A classic Shaker ladderback rocker. This piece is in the collection at the Pleasant Hill Shaker Village in Kentucky. Plans to build this type of chair can be found on page 154.

THE SHAKER THE SHAKERS:

A NINETEENTH-CENTURY GENIUS

In 1774 Mother Ann Lee, founder of the Shaker sect, and eight followers, traveled from Manchester, England, to the New World in search of greater freedom of religious expression. She was herself strongly influenced by the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers. In their early years this new collectivity came to be called “Shaking Quakers,” a term derived from certain movements performed in their liturgy. This name was later shortened to Shakers, although the sect is officially known as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing. Like the Quakers, the Shakers were pacifists who avoided politics, theater, strong drink and “vain amusements” of every sort. They wore simple clothing, spoke in simple terms, lived in simple surroundings. Their way of life was clearly the antithesis of materialism. Today a single stone marks the graves of all at New Gloucester, Maine. On its face is inscribed “SHAKERS.”

The earliest Shaker settlements were at Watervliet and Lebanon, New York; Hancock and Harvard, Massachusetts; and Enfield, Connecticut. Later, as the number of converts grew, settlements were established in Maine and New Hampshire. By the middle of the nineteenth century there was a total of nineteen communities extending as far west as Pleasant Hill, Kentucky.

Not unlike other sects of the periods, such as the Oneida Community in upstate New York, the Amana group of Iowa, and the idealists of New Harmony, Indiana, the Shakers envisioned a religious, political and social utopia. Celibacy, communal ownership of property, and a reverence for perfection in work characterized their lives. It is all but impossible for us in the 21st century to understand, let alone empathize with, this pervasive selflessness. Yet in this chapter of American history, Shakerism flourished, both spiritually and economically. The Shakers achieved a social order based upon equality, sharing, and personal anonymity. At the heart of the creed was Christ’s Second Coming, for, as set down by Mother Ann Lee, Christ was ever present within the soul of each member and within the community per se. This presence is made manifest in all aspects of Shaker life, particularly in the products of their craftsmanship. Her admonitions, “Put your hands to work and your hearts to God,” and “Do your work as though you had a thousand years to live, and as if you were to die tomorrow,” serve as a philosophic/religious basis for a high level of perfection in craftsmanship. The overriding characteristics of Shaker work are unity and simplicity. Unity of material and function bespeak the functionalism of a much later day where order and system are the cornerstones. To the Shakers, ornamentation of any sort was considered vanity, useless ostentation. Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity.

This adherence to economy of form had its detractors outside the community. Upon visiting a Shaker room at Mt. Lebanon, Charles Dickens wrote, “We walked into a grim room, where several grim hats were hanging on grim pegs and the time was grimly told by a grim clock.” Had Dickens been born a hundred years later, he might well have used another, less pejorative adjective, for he saw Shakerism from a Victorian’s perspective, which was colored by burdensome levels of ornamentation.

What is most awesome is the sheer volume of Shaker inventiveness. They are reputed to have invented the automatic washing machine, the circular saw, the steel pen, water-repellent clothing, the one-piece clothespin, the self-feeding surface planer, and much more. How was it that a movement consisting of fewer than six thousand souls at its height, around 1850, could produce such a prodigious array of inventions, machinery, foodstuffs, medicines, and products for farm and home?

To the followers of Mother Ann, time “was the taskmaster of toil.” The artifacts left by the collective genius of the Shakers are testimony to their abiding need for efficiency as well as self-sufficiency. Few things were purchased from “the world,” and in the early days few things were sold. As their numbers and strength grew, of course, commerce led them to greater levels of economic assimilation. Indeed, it was this assimilation, and the advent of true industrialism, that sounded their death knell in the twentieth century.

Today, the Shaker community consists of only three members at the Sabbathday Lake, Maine community. They function as repositors and custodians of the movement, and new members are welcome. For details visit www.shaker.lib.me.us.

Indeed, as a relevant contemporary religious and economic force, the sect has only minor influence now. However, the artifacts left by this relatively small group have never before so captivated and moved us.

SHAKER ANTIQUES

Over the last sixty years Shaker furniture has been “discovered.” Any discussion of American decorative arts now includes a section on Shaker design, and no comprehensive American museum of any size could function without a Shaker Collection. Indeed, during a visit to the American Museum in Bath, England, my wife and I were delighted to find there one of the most exquisite collections of early nineteenth century Shaker furniture and household tools. The warm reception of this style by the English attests to its international appeal. This receptivity is shared by the Japanese, who are enchanted by these clean, uniform lines.

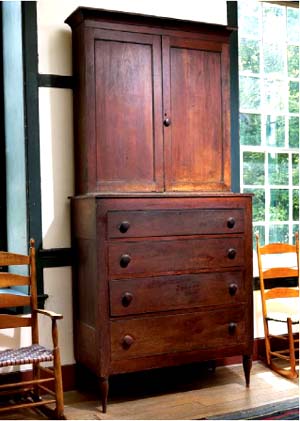

This cupboard on chest shows a style of drawer graduation that we have come to regard as normal, with the larger drawer at the bottom and its smallest drawer at the top.

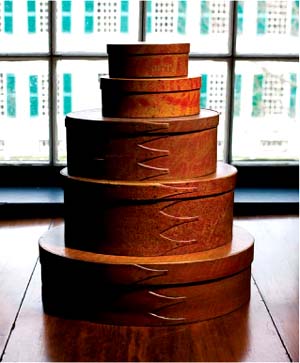

In the antiques market Shaker items command unheard-of prices. Recently, at an auction dedicated exclusively to Shaker artifacts in Kezar Falls, Maine, an ordinary grain sack bearing the Shaker name was reportedly sold for $240. Sets of the small wooden oval boxes, which were produced in New Gloucester scarcely a generation ago, are now selling for hundreds and hundreds of dollars. I remember hearing the story that after World War II an entire meetinghouse full of Shaker chairs was put to the torch because they were considered unmarketable. Today an authentic Shaker chair fetches upwards of $800.

Two years ago we contributed a small round stand of our manufacture to a local television auction. The auctioneer, thinking at first it was an original Shaker piece, exclaimed that the bidding should start at $1,400. The table, because it was not of Shaker origin, sold for one tenth that amount.

One cannot visit an antique shop without finding a horde of so-called Shaker collectables. In just one issue of an antiques magazine published here in Maine no fewer than seventeen furniture items were advertised as being “genuine” Shaker. Enormous prices, coupled with a real dearth of supply, have caused many an eager antique dealer and collector to see Shaker where there is none. To have produced such a voluminous array of furniture in a period of thirty years or so, and for these many examples to have survived a hundred years of fires, flood, and other calamities, 60,000 Shakers would have had to work twenty-four hours a day building Shaker tables, boxes, clocks, and so on, and painting them in the old red!

Most of this mislabeled furniture is neither reproduction nor fake. It is, rather, an assortment of pieces made of the same materials and at approximately the same time in approximately the same style as the Shaker originals. In other words, with a few exceptions, Shaker furniture is to a great extent indistinguishable by most non experts from other country-made primitives of the period.

THE ORIGINS OF SHAKER DESIGN

In order to understand how this could happen one must remember that the Shakers were celibates, and as such no new members could be born into the church. Growth was predicated upon propagation, not procreation. And although many of the converts were brought up from childhood in the Shaker communities, the preponderance came from the outside world as adults, adults replete with trades and traditions. To be sure, most were farmers, but some were also carpenters. And the best carpenters became cabinetmakers and chairmakers. Many of the Shaker joiners had their apprenticeships in secular cabinetmaking shops whose masters knew nothing of Shakerism. As such, they learned the art of joinery from master artisans who were themselves strongly influenced by styles and trends of the time. Naturally, when these builders joined the church, they carried these tastes and styles with them.

In fact, the evolution of Shaker furniture style runs more or less concurrent with the evolution of American country furniture style in general. In the cities, of course, there were large shops which produced in the grand style much of what we today call “period furniture.” Designs by Thomas Chippendale were executed in New York, Philadelphia, and Newport between 1760 and 1800. After the Revolutionary War the intricate inlay work and elaborate fluting of Hepplewhite and Sheraton were produced in what is now called the Federal period, from 1780 to 1830. These period styles were copied by most cabinetmakers of the day, but the further from the city the copier, the less elaborate and ornamented the work appears. The rural builders lacked not only the skills and materials to do multichromatic inlays, for example, but also customers to whom they could sell them. Simple rural families needed a table off of which they could eat, not a status symbol. And so we have, passed on to us over the generations, what is called Country Chippendale, Country Hepplewhite, and Country Sheraton furniture.

This legacy is characterized by simple lines, the absence of superfluous decoration, and a sturdiness of construction rather than a delicacy. While the Goddards and the Townsends and the Phyfes were building in imported solid mahogany and exotic veneers, their country counterparts were building in pine, poplar, birch, cherry and maple — woods native to America. In order to achieve the look of mahogany they often stained their work, using an oil-based wiping stain, or used buttermilk paint to seal and conceal its humble origin. Not uncommonly, they resorted to “graining,” which yielded oak, mahogany, and rosewood patterns and colors. Indeed, some were so proficient that from a distance even someone who should know better may mistake pine for rosewood. The employment of grained paint and stenciling was nowhere so evident as at the Hitchcock Chair Factory in Connecticut, where, even today, birch, pine and maple are grained to look like rosewood.

The Shaker style therefore has its origin squarely in the secular world from which it drew its practitioners. And since style changed in the “world,” so, too, it changed within the sect. In the Shakers’ developmental years, from 1775 to 1800, only the crudest furniture was built, and that in small amounts. The few pieces that survive are strictly country primitives not unlike any other products of rural New England and Upper Hudson Valley. But in their struggle to overcome worldliness, their physical and social separation gradually led to a conscious effort to imbue furniture designs of the period with purity and simplicity. Since order, cleanliness, and simplicity were to be ever-present in their daily actions and thoughts, it is little wonder that these principles should be manifest in their furniture and other domestic appurtenances.

An iconic Shaker image is that of the graduated oval boxes. These boxes were used for a variety of storage needs in the community.

Before electric lighting, rooms were lit with lanterns or candles. This cleverly-designed sconce was created to hold a single candle at a height that could be adjusted according to need.

The period between 1820 and 1850 was the Shakers’ golden age of design, a kind of Periclean age during which pure forms spilled forth. Forms light in expression, well balanced, not excessive in any regard, were produced for domestic use. This period is also noted for its exquisite workmanship. Joints were delicately made, and the handling of wood reached perfection. Understatement and effortlessness seem to permeate much of the period. Finishes were applied with care, and still perform even today the task of stabilizing and enriching the grain.

The New Lebanon Church family, the largest eastern community, was the “fountainhead” of Shakerism. It was the home of the central ministry and also the place where the definitive Shaker form was produced. Articles made there often served as samples for the guidance of other makers in other communities, although all artisans were free to express themselves within broad church doctrine. While still bearing a resemblance to Hepplewhite and Sheraton, these forms evolved to unique dimensions. A new vocabulary in design was achieved and became a pervasive influence in exterior and interior architecture and furnishings. The starkness of white plaster rooms is broken by horizontal chair rails and pegboards. Windows and doors are trimmed using a minimum of material. Storage room is achieved by architectural built-in cupboards and drawers, and these blended with other interior features to produce a quiet eloquence. Order and cleanliness prevailed in their living, working and worshipping spaces.

After 1850 Shaker furniture went into decline. With greater worldly intercourse came a profusion of Victorian production. The excesses of the genre steadily degraded an earlier perfection, and by the turn of the twentieth century no Shaker furniture of consequence was being produced.

Though short-lived, the early nineteenth-century golden age produced a collection of truly remarkable furniture. The complex influences of religious and social systems led to the creation of a truly inspired form.

THOS. MOSER, CABINETMAKERS

Thos. Moser, Cabinetmakers, began producing furniture in the Shaker style as early as 1972. In the beginning a dozen or so designs from circa 1830 were built more or less as reproductions of Shaker originals. Measured drawings were consulted and followed meticulously. There is a place for copying in the development of any craftsman. For it is through faithful imitation that certain otherwise obscure principles can be learned. Any skill, be it woodworking, oratory, or surgery, can best be learned in the shadow of a master. In a sense, the designer-practitioner should be able to work within the discipline of “proven” or demonstrable systems of the past before he plunges blindly into the future. I lack respect for the painter who has not mastered his craft so as to be able to produce representational art even though he practices abstract expressionism or nonobjective art. All too often the college sophomore art student begins splashing about as an avowed abstractionist “expressing” a full range of emotions without first being able to mix color, achieve unity or balance, and create disciplined form. One cannot run until one has learned to walk. Similarly, the furniture designer and cabinetmaker whose entire background begins and ends in a single contemporary idiom does himself a disservice. In developing our craft here in New Gloucester, we have built in the period style, with its exacting carving and graceful ornament; we have built contemporary forms, with laminated components; we have built architectural assemblies, doors, mantels and spiral staircases; we have made knife handles, waterwheels, wooden tools. My definition of a cabinetmaker is one who works in wood and has a broad design repertoire, but it is the wood, the medium, which sets him apart from other craftsmen. Only the inherent nature of wood limits his repertoire.

There are many ways one can learn the art. The old system of apprenticing oneself for five or seven years to a master is virtually defunct today both here and in Europe. The demands of the marketplace rule this out. Where there are apprenticeships established, production schedules and the goddess Efficiency rob the apprentice of the time necessary to make mistakes. Apprenticeship programs within restoration projects, such as Williamsburg or Sturbridge, are conceived for the enlightenment of the viewers, not the apprentice who is often little more than an interpreter. Still, one can learn from past masters, if not directly, the at least through their work. I have disassembled, repaired, and reassembled hundreds of antiques built fifty or a hundred or three hundred years ago. These afford a kind of classroom, as it were, a chance to observe in three dimensional form the work of anonymous joiners long departed from this life. In taking apart a piece, in studying its joint system, in seeing and feeling the marks left by a backsaw and chisel, one can imagine himself at the side of the maker. I delight in experiencing this re-creative process. I wonder during what season a piece was built, for whom, where the wood came from and how it was cut, what the maker had on his mind as he labored, what time of day it was built. The joy of opening a joint that has not seen daylight since its making is like discovering an author whose notions on this topic or that are exactly like one’s own. One feels a close rapport, an intimacy in communication, that is rare and to be savored.

Though not a small piece, this hanging cupboard conveys a feeling of lightness by using a thin (3⅜8”) top piece.

With experience one learns to anticipate what to look for in ancient cabinetry, since the methods of joining are relatively few and, in time, become predictable. Unlike today’s craftsmen, the old-timers didn’t have a convenient glue and therefore used it sparingly. It is for this reason that our task of disassembly and repairing is made so much easier. I often think the eighteenth-century joiner knew that some day his work would be so exposed. Why else would he have been so precise in stamping Roman numerals on the pieces of a joint inside of the joint itself? Or why would he take the time to gently chamfer all the edges of a concealed tenon? When inspired, I will often write a message inside a joint or under a support or hinge in hopes that someday, years hence, somebody will read my message about Watergate or the temperament of my oldest son, Matthew.

Not all the work of the past was necessarily well done. Some antiques, although they are old to be sure, are often poorly designed and occasionally poorly built. Be that as it may, I like to say I learned my art from dead men, for indeed these builders of the past are gone, but not without a trace. Their work remains, not only in the collections of fine museums, but also in antique stores and attics and homes and junk shops where it may have to be exhumed from beneath thirty-two coats of paint. My greatest pleasure is to buy a basket case, a piece so badly mangled that it literally must be carried to the shop in a container. A leg, a drawer front, the painstaking removal of all but the first coat of paint, and there before the eyes of the world it stands-now a product of two builders, one dead, one living.

The pieces pictured in this book and drawn to scale had their origins in this way: they are the evolutionary result of trial and error, of textbook consultation and basket cases and many false starts. Most of these pieces have had their last design change; they are as perfect as I am able to make them. Some are still in the process of becoming. Dimensions, it seems, are always changing. We will build a chest with a 32”-height, thereby achieving the golden mean, Aristotles’ vision of perfection, only to discover that most people prefer a 34”-height because it makes carving a turkey more convenient. In building the first “two-stepper” we followed a Shaker prototype. It turned out to be far too unstable to use with confidence. If one were to build furniture today to exactly the scale used by a Shaker community of 1830, he would be building for prepubescent children, since today’s adults are fully four inches taller than Americans of 150 years ago. Similarly, table heights, chair widths, place-setting intervals, counter heights, book size, window sill elevations, chair rails, kitchens, have become somewhat standardized. In arriving at these designs, standard contemporary practices are taken into account to make each piece as usable as possible.

Variations between Western and Eastern Shaker communities are easy to find. The thickness of the top and of the legs on this table mark it as of Western construction.

The drawers on this cupboard are graduated in the reverse of what we consider “standard”, with the smallest at the bottom

Blanket chests were a staple of storage long before closets.

Also taken into account is the availability of wood in precut and dressed sizes. To be sure, the designer should be committed only to function when conceiving a form, but an ideal form that cannot be built because the materials do not exist or are too costly remains forever an ideal and not a reality. As discussed in Chapter 2, the lumber industry has standardized dimensions to such an extent that in order for the private cabinetmaker to have a supply of all sizes he would have to either fill a warehouse or have an elaborate system of resaws and dimension planers. Therefore, most of these designs require three-quarter-inch material in commonly available widths and lengths. When smaller thicknesses are required, they can be gleaned from this basic dimensional lumber. In fact, throughout, standardization is attempted in fasteners, hardware, and general dimensions.

The ladderback chairs, for example, are the product of a number of trials which have resulted in an altogether pleasing form utilizing only three spindle sizes. In fact, these same three spindles can be used to build eight different chairs. Some of the case pieces also exhibit standard size in width and depth and are designed to satisfy today’s storage requirements.

The chief difference between these designs and their Shaker prototypes, aside from the dimensions, is consistency or uniformity of detail. While not conceived as an ensemble, or “suite” in the vernacular, these pieces can be built and arranged in such a way as to furnish a complete study, bedroom, or dining room, as well as occasional settings of various sorts.

The Shakers lived austere lives quite unlike our own, their functional furniture requirements were obviously quite different, and so, when necessary, preference is given to contemporary function over historical accuracy. To my knowledge, the Shakers did not make or use open-shelved cupboards; yet one is included here, although its origin is a much earlier Massachusetts pewter cupboard design. Several tables are included which are not strictly Shaker. The hutch table, with its somewhat massive base, the harvest table, and the round extension table are all basic Hepplewhite forms certainly within the Shaker sentiment, but they are not Shaker. These liberties are taken to provide a wider array of useful designs not found entirely within the collection of surviving Shaker antiques.

Shaker’s beds were primarily functional, but frequently beautiful in their simplicity and construction.

Moulding details, drawer pulls and door details are also quite stylized. Similar cupboards, for example, from different communities would have displayed quite dissimilar features and it is impossible to say that one detail is more truly Shaker than another. Experience shows that the Shaker joiner used raised, flush, and plain panels in door construction. He also used thumbnail, squared, and ridged mouldings in the door styles. Most of our designs use the raised panel and squared style because I find it most pleasing to the eye and most in conformity with the general style of the furniture in this collection.

In constructing from these drawings, the builder is encouraged to change details to suit his individual taste and need. Only proportion should hold more or less constant.

Although most of the pieces are photographed in cherry, they can also be built in another hardwood or even in pine. Indeed, most of our early work was in pine, usually painted or stained. This treatment has a rather limited appeal, however. Even among Shaker purists, painted pine does not compare with the color and richness of oiled cherry left in a natural state. Occasionally we are commissioned to build in cherry and to cover either in stain or paint. Nothing is more painful.

This collection does not lend itself to highly polished finishes. Although other kinds of finishes are occasionally used, including urethane and varnish, experience has taught us that an oil and wax treatment is by far the most satisfying in the long run.