APPENDIX II

A Note on Budget Projections

The CBO’s long-term projections have received a great deal of attention in the media. Under its so-called current-law projection, the CBO shows that federal debt will rise to 106 percent of GDP within twenty-five years. At that level, debt would be higher than it has been at any point in U.S. history except for one year around World War II. It would be much higher than the 35 percent of GDP that it was in 2007—and the 24 percent of GDP that it has averaged since 1790. The CBO warns that high and rising levels of debt would harm our economy.

However, as disquieting as those projections are, I believe they seriously understate the true magnitude of the long-term fiscal challenges facing the United States because they are based on a number of optimistic assumptions about future budget policy. For example, they assume that discretionary spending will be sharply constrained, unpopular sequesters will remain in place, physician reimbursement rates under Medicare will drop dramatically, popular tax breaks will be allowed to expire, and revenues will rise well above historical averages.

If lawmakers fail to stay on this assumed path of fiscal restraint, federal debt will soar sharply above 100 percent of GDP. For example, the CBO shows that under an alternative fiscal scenario that makes less optimistic assumptions and incorporates the negative effects of debt on the economy, federal debt would skyrocket to 183 percent of GDP within twenty-five years.

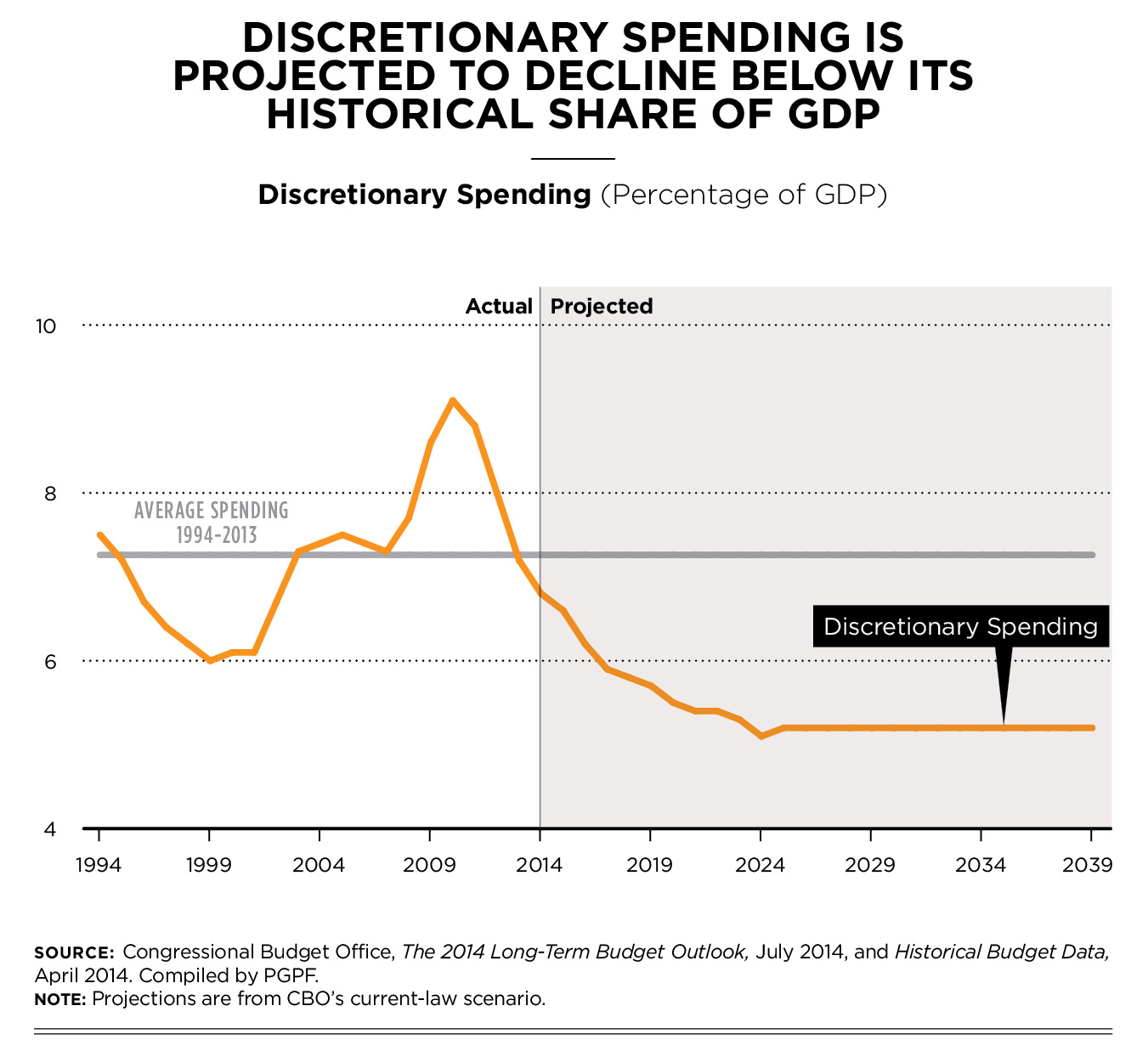

The assumptions about discretionary spending in the current-law projections are especially implausible. These discretionary programs are an important part of the budget and cover a wide range of government activities including defense, scientific research, infrastructure, and education, as well as law enforcement, national parks, NASA, food safety inspections, federal pay, and grants to state and local governments.

In its current-law projections, the CBO assumes that spending on those programs will decline significantly from 7.2 percent of GDP in 2013 to 5.2 percent of GDP in 2025 and then remain at that low level thereafter. Although current law imposes tight caps on discretionary spending through 2021, it seems very doubtful that lawmakers would adhere to such tight restraints indefinitely. At 5.2 percent of GDP, discretionary spending would be well below its average of 7.3 percent of GDP over the past twenty years—and below the lowest point it has been in the past fifty years, which was 6.0 percent of GDP in 1999.

Indeed, Congress has already had great difficulty bringing discretionary spending under the budget caps for 2014. If lawmakers had trouble reducing discretionary spending in 2014 when it was 6.8 percent of GDP, is it plausible to expect that discretionary spending will be reduced to 5.2 percent of GDP in coming years?

And if lawmakers actually achieved that target, would it be a wise and sensible choice for the nation? Discretionary spending funds many programs that could help our economy grow, such as infrastructure, R&D, skills training, and education. How will our nation be able to succeed in a vastly more competitive and technological global economy if discretionary programs are constrained so tightly?

The current-law projections also embody a number of other optimistic assumptions about future budget policy. They assume that Medicare’s reimbursement rates for physicians will drop by about 24 percent on April 1, 2015 as required by current law, even though policymakers have overridden those reductions many times in the past.

On the revenue side of the budget, the current-law projections assume that a large number of tax provisions will expire in coming years as scheduled under current law. In the past, lawmakers have routinely extended those provisions, yet the CBO’s current-law projections assume that all of those tax provisions will expire permanently. These provisions include the tax credit for research and experimentation.

Finally, the CBO’s current-law projections assume that lawmakers will not change the tax code even as more and more taxpayers are pushed into higher tax brackets as their real incomes rise. This will have significant—and unintended—consequences on many middle-class and poor households. For example, under current law, the CBO estimates that the fraction of Social Security benefits subject to tax will climb from 30 percent to 50 percent over the next twenty-five years, and the value of the personal exemption relative to income will fall by more than 30 percent. As the CBO notes in The 2014 Long-Term Budget Outlook: “If no changes in tax law were enacted in the future, the effects of the tax system in 2039 would differ in significant ways from what those effects are today. Average taxpayers at all income levels [emphasis added] would pay a greater share of income in taxes than similar taxpayers do now.” Although all taxpayers would face a higher tax burden under continuation of current law, low-income taxpayers would be significantly affected. For example, the effective income and payroll tax rate paid by single taxpayers with half the median income would climb by 38 percent over the next twenty-five years under current law, according to the CBO.

Because many of the assumptions beneath the current projections can be questioned, the CBO also prepared an alternative fiscal scenario. In that scenario, discretionary spending gradually rises back up to its historical average in the long run; the sequester is repealed; Medicare’s scheduled reduction in physician reimbursement rates is overridden; expiring tax provisions are permanently extended; and revenues remain at 18.0 percent of GDP in 2024 instead of rising to 19.4 percent of GDP in 2039 (and to 23.9 percent of GDP in 2089) as they would under current law. The CBO also incorporates the feedback effects of rising debt on the economy in some of its projections. As debt rises, it crowds out capital investment, reduces productivity, and slows the growth of wages and incomes. Higher debt also puts upward pressure on interest rates in the CBO’s alternative projections, causing interest costs to climb, which accelerate the growth of debt.

Under the alternative fiscal scenario, the CBO estimates that federal debt would climb to 183 percent of GDP within twenty-five years. At these levels, debt would be in territory that would be very hazardous to economic growth.