IN AN OLD house not far from Juniper Street in Little Spring Valley lived Pandora and Marvel Treadupon and their three children. Pandora and Marvel were quiet people. They were fond of sitting on their back porch and doing absolutely nothing but listening to the birds chirping or the wind blowing. They preferred reading to talking. They held hands and smiled at each other and their children, and they enjoyed a good laugh every now and then, but they kept conversation to a minimum, and they spoke in low tones. That was just how they liked things.

For years, the Treadupon household had been so peaceful that it was the place where other parents on the street sent their children when they needed to settle down. Their next-door neighbors, the Figs, used the Treadupon home when their own children needed a time-out. One day when Mrs. Fig had asked her daughter Fedora to please clean up her bedroom, Fedora had replied, “Why don’t you clean it up if it bothers you so much?”

Mrs. Fig, horrified, had said, “You need a time-out, young lady.” Then she had looked around at the chaos in the house and said, “March next door. Right now.”

Fedora Fig had headed for the Treadupons’ home and sat in their silent, boring kitchen corner for ten minutes. Pandora Treadupon had waved to her from the back porch, where she was drinking tea and listening to the birds, but she hadn’t said a word.

The Treadupons had three children—twelve-year-old Tallulah, ten-year-old Marvel Junior, and five-year-old Einstein. Their lives had been just as calm as calm can be until Einstein turned two. That was when he’d started speaking in complete sentences. Suddenly, the Treadupon home exploded with chatter, and it was all Einstein’s. While his father was content simply to listen to the birds, Einstein would jump up and down beside him and exclaim, “Do you hear that? Do you hear that? That’s a pileated woodpecker, scientific name Hylatomus pileatus. It inhabits deciduous forests. Do you know what deciduous means?” Without waiting for an answer, he would hold up his index finger and go on. “Fun fact! The holes woodpeckers make in trees become shelters for bats and birds.”

While Einstein jumped up and down expounding on woodpeckers, his jacket and tie flapped about. Einstein always wore a suit. He carried a briefcase. And he insisted on being addressed by his complete formal name: Einstein J. Treadupon. He referred to his mother and sister as Ms. Treadupon and his father and brother as Mr. Treadupon.

There was nothing Einstein J. Treadupon couldn’t talk about—dinosaurs, silverware, books he’d read, gum he’d found on the sidewalk.

And he was only five.

“He’s a genius,” Pandora would say wonderingly to Marvel Senior. “Our son is a genius. We mustn’t stifle him.”

“We must allow his interests to grow.”

“To unfurl like petals on a flower.”

Some of the Treadupons’ neighbors, the Figs in particular, had a different opinion of Einstein. They didn’t mind his suit and tie, but …

“He never stops talking!” Fedora complained to her mother.

Mrs. Fig didn’t want to say so, but privately she felt that Einstein was like a windup toy that couldn’t be shut off.

“And most of what he says is not at all interesting,” Fedora continued. “Like when he talks about wood.”

Emmy Fig, who was in Einstein’s kindergarten class, said, “He never raises his hand. He interrupts Mr. Graham seven billion times a day.”

Mrs. Fig shook her head. She was sorry to have lost her time-out spot in the Treadupons’ kitchen, which, now that Einstein could talk, was no longer a calm oasis.

“I feel a little sorry for Pandora and Marvel,” ventured Mrs. Fig over dinner that night.

“I don’t,” her husband replied. “What did they think was going to happen when they named their child Einstein?”

Next door, the Treadupons were also eating supper. The five of them sat at the table in their dining area. Einstein J. Treadupon’s briefcase leaned against his chair. Mr. Treadupon passed around plates of rice, broccoli rabe, and baked chicken. Back in the time before Einstein had learned to talk, Pandora, Marvel Senior, Marvel Junior, and Tallulah would have smiled at one another and spoken politely about their days. They used to have conversations like this:

MARVEL JUNIOR: Beaufort Crumpet let me feed his bunny this afternoon.

PANDORA: How lovely, dear.

MARVEL SENIOR: I’ve been thinking that we might go to the beach this summer.

TALLULAH: Oh, a vacation. Wonderful, Father.

Then there would have been a five- to ten-minute pause while everyone chewed their food, thought about rabbits and the beach, and listened to the classical music playing in the living room.

At last Marvel Junior might have said: Is there anything for dessert?

PANDORA: A special treat. I’ll give you some money when the ice-cream truck comes around.

TALLULAH: Splendid. Thank you. I’ll just start my homework while we wait for the truck.

Of course, the Treadupons could hear the ice-cream truck no matter what the season, even if their doors and windows were closed, since their house was so quiet that they could catch the sounds of things happening blocks away.

Now all that had changed. On the night of the chicken and rice and broccoli rabe, Marvel Junior politely waited for a break in a lecture Einstein was delivering on Stilton cheese, and then said in his soft voice, “Could someone please pass the broccoli rabe?”

Einstein hooted. “Wrong! Mr. Treadupon said broccoli rab-ay! As everyone knows, r-a-b-e is pronounced ‘rob’.”

“Well…” said Pandora, but her voice trailed off into nothingness.

“Fun fact!” her youngest child barreled on. “Broccoli rabe is a member of the Brassicaceae family, otherwise know as the mustard family.” He reached for his briefcase, popped it open on his lap, and rustled around inside for his iPad and a sheaf of important-looking papers.

Pandora and her husband glanced at each other across the table. Their glance said as plain as day, A genius! Our five-year-old is a genius!

“Regardez,” Einstein J. Treadupon continued. Occasionally he slipped into French, a language neither of his parents spoke. They didn’t know how he had picked it up.

Tallulah leaned over to look at the papers. “Oh! You have information on all the—”

Einstein raised his voice a couple of notches, which is what he always did when he interrupted someone. “I’VE BEEN RESEARCHING THE GENUS (PLURAL GENERA),” he shouted over his sister, “and the species of families in the plant and animal kingdoms.”

“Brilliant,” murmured Marvel Senior.

“But Father, he interrupted me,” Tallulah pointed out. “Einstein, it isn’t nice—”

“YOU KNOW WHAT ELSE?” Einstein barged on. “In school today, Mr. Graham gave us a snack, and what do you think it was? Graham crackers! Graham crackers from Mr. Graham! And also we’re going on a field trip. The kindergarten field trip is always to the firehouse.” Einstein paused long enough to put a spectacularly small piece of chicken in his mouth.

“I remember my trip to the firehouse,” said Marvel Junior. “Einstein, it’s so cool. You get to—”

“EXCUSEZ-MOI, but I would like to remind everyone to refer to me by my formal and proper name, Einstein J. Treadupon.”

Marvel Junior (who in truth thought his own name was too long and would have preferred to be called Marv) rested his chin in his hands. He found that he often wanted a nap after spending more than a few minutes with his brother.

“We have to choose partners!” cried Einstein, who had swallowed the speck of chicken. “How are we supposed to do that when there are seventeen kids in my class? Seventeen is an odd number, not to mention a prime number. Someone will have to have Mr. Graham for his partner, I guess. I hope my partner isn’t Ms. Fig.”

“Who’s Ms. Fig?” asked Einstein’s father.

“Mr. Treadupon, my goodness, you know who Ms. Fig is. She lives next door. She’s in my class.”

“You mean Emmy?” asked Tallulah.

“Who else? Ms. Fig never says a word. She’s so boring. Vraiment, all my classmates are boring. By the way, did you know that the firehouse was built in 1920? It’s going to have a big birthday soon.”

Marvel Junior gazed at his little brother. “I wonder why it is that Emmy never says anything. Have you noticed, Einstein J. Treadupon, that no one can say anything when you’re—?”

“HEY, LOOK! Look out there!” cried Einstein, pointing out the window.

“What is it? A cardinal?” asked Pandora. “I saw a pair of cardinals this—”

“NO, I JUST WANTED to make you all look. That’s a joke! Made you look! Made you look! I have a joke book here in my briefcase. I took it out of the library today. The joke book, I mean.”

Pandora sighed wearily. “Darling,” she began, addressing her young genius.

“The name is Einstein J. Treadupon.”

“It might be polite,” his mother continued, “to let—”

“AU REVOIR!” roared Einstein. “I must begin my homework.”

“Mr. Graham gave you kindergarten homework?” asked Tallulah, frowning.

“Oh no. I gave it to myself.” Einstein closed his briefcase and slid out of his chair, leaving his dinner largely untouched. His work was far more important than nourishment.

The remaining Treadupons let out sighs of relief and ate the rest of their dinner in utter silence.

* * *

The next day, Pandora spent all morning and part of the afternoon working at her desk. She was researching the habits and migration patterns of hummingbirds in preparation for a long article she’d been asked to write for a scientific journal. She concentrated so long in the lovely, delicious silence that when she heard a loud voice at her elbow, she jumped and knocked over a glass of water.

“Good afternoon, Ms. Treadupon. Or perhaps I should say bon après-midi,” said Einstein. He stood at his mother’s elbow, carrying his briefcase and a black umbrella. He stared at the water dripping from the overturned glass onto the floor and added, “Did you know that water can exist in liquid, solid, and gaseous states?”

“Darling, do you see that you startled me? You might consider apologizing—”

“AND THAT ITS chemical formula is written H2O, meaning that it consists of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom? Also, as I have reminded you numerous times, including just last night, I would prefer to be addressed as Einstein J. Treadupon.”

Pandora rubbed her temples with her fingers. She stared down at her desk, and her eyes fell upon a copy of the Little Spring Valley Weekly News and Ledger. Staring right back up at her, as if it were a sign, was a notice with cheerful lettering reminding readers of story time at A to Z Books that very afternoon.

Pandora’s eyes widened. “Einstein J. Treadupon,” she said, “I have a surprise for you. This afternoon we are going to go to story hour at the bookstore. It starts at four o’clock. Perfect timing. Your brother and sister can go with us.”

“Wrong! As everyone knows, story hour is for babies,” Einstein replied.

“Not according to the newspaper. It says it’s for all ages. Today Mr. Spectacle is going to begin Stuart Little. Remember when we read Charlotte’s Web? You had so many—”

“FUN FACT! Stuart Little is about a mouse, and just today I learned that baby mice are called pups.”

Pandora rubbed her temples again. Four o’clock couldn’t come fast enough.

* * *

Across town in the upside-down house, Missy Piggle-Wiggle stepped over a fat orange extension cord that snaked up the stairs to some piece of equipment Serena Clutter had brought inside and answered the ringing phone that Lester handed her. She listened for a moment, then said, “That sounds lovely, Harold. Of course I’ll come. I’ll see you a little before four.” She clicked off the phone and smiled at Lester. “I think I might have a date. Harold just invited me to story hour at A to Z Books.”

Half an hour later, Missy set off for town. She was surrounded by Melody, Veronica, the Freeforall children, and Beaufort Crumpet. They had been playing at the upside-down house, which was once again open to the children in town, but only if they stayed out of the way of Serena and her team, and they were frankly tired of dodging them. When they reached Juniper Street, the children ran ahead of Missy and crowded into the store. Missy followed more sedately. She stopped outside the window and, while pretending to look at a display of picture books about April showers and May flowers, adjusted her straw hat and patted her wild red hair into place. Then she entered A to Z Books. The door, which sneezed rather than ding-donged when it was opened, announced her arrival with an alarmingly realistic AH-AH-AH-CHOO!

“Missy, you’re here,” said Harold warmly, clasping her hand between both of his. “Please have a seat,” he added gallantly.

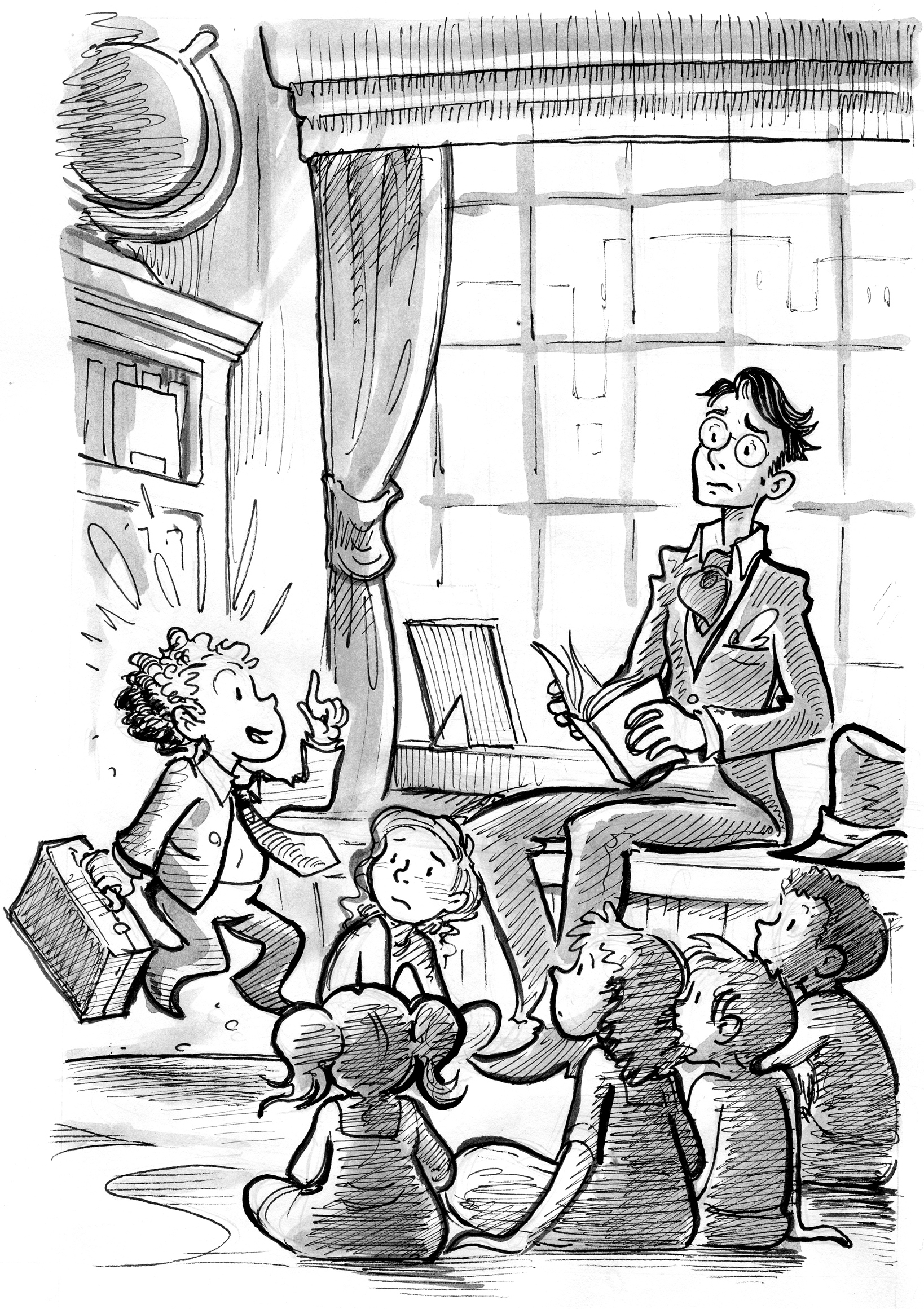

Missy glanced at the row of chairs that had been arranged along the back wall for the adults. Then she plopped down onto the floor with the children. She looked around the crowded store. In addition to Veronica, Melody, Beaufort, and the Freeforalls, she saw Rusty and Tulip, Linden Pettigrew, Samantha Tickle, and Della and Peony LaCarte, sisters who most adults in town thought to be absolutely perfect. The door sneezed again, and in walked a very tired-looking mother followed by a girl of about twelve, a younger boy, and then a very small boy who was dressed in a suit and carrying a briefcase and an umbrella.

Samantha Tickle let out a groan.

“What’s wrong?” Missy asked her.

Samantha turned desperate eyes on Missy. “See that boy with the briefcase? That’s Einstein J. Treadupon. He’s a smarty-pants. He never lets anyone say anything because he talks all the time. He’s not interested in what other people have to say. Which is SO RUDE.”

“That tiny little boy?”

“Yes.”

“He isn’t talking now. He’s reading something in his briefcase.”

“Well, just wait,” said Samantha. Then she put her hand to her forehead and added, “The entire day is ruined.”

Missy looked for the rest of the Treadupon family and saw that they had seated themselves as far as possible from Einstein. She noticed an empty chair next to Mrs. Treadupon and decided to sit there instead of on the floor. She and Einstein’s mother had just exchanged smiles when Harold stood up and addressed the audience.

“Thank you all for coming today,” he said. “I see some familiar faces and some new faces. Today we’ll begin reading Stuart Little, by—”

“It’s by E. B. White!” announced Einstein. He snapped his briefcase shut. “E. B. White also wrote Charlotte’s Web and The Trumpet of the Swan. AND he wrote for adults. He was a crossover—”

Harold plastered a smile on his face. He tried to talk over Einstein. “Thank you,” he interrupted him. “Stuart Little is a book that appeals to all ages, so it’s a perfect choice for our story hour. I’m happy to see plenty of adults here today as well as young people. The last book we read was—”

“THE LAST BOOK WE READ in my class at school was a picture book,” said Einstein, “and in my opinion, it would have been appropriate for a much younger audience.”

“Wonderful, wonderful,” murmured Harold. He leaned his cane in a corner and sat on a chair at the front of the crowd. A tiny girl reached out to touch one of his polished purple shoes, and Harold smiled at her. He opened Stuart Little, glanced nervously at Einstein, and began reading. He had read for approximately one minute when Einstein jumped to his feet and said, “In case anyone is confused, the reason it says in the story that first-class mail is only three cents is because the book was published in 1945.”

The small girl who had stroked Harold’s shoe began to cry. “Why did you stop reading?” she wailed.

Missy looked at Mrs. Treadupon and saw that she was pretending to search busily through her purse. She looked at Harold and saw that he was looking at Mrs. Treadupon, too. Mrs. Treadupon kept up her desperate search. At last Harold said, trying not to focus directly on Einstein, “I would just like to remind everyone that it would be polite to hold all comments until I’ve finished reading today. Or at least until the end of a chapter. There will be plenty of time for discussion later.”

As you might imagine, story time with Einstein in the audience was neither entertaining nor relaxing. He jumped up and down, referred to papers in his briefcase, and announced many facts that were fun only for him. One time he leaped up to exclaim, “Did you know that a pound of feathers weighs exactly the same as a pound of pennies? It’s just that you need a lot more feathers than pennies to make up a pound.”

“Excuse me,” said Rusty, “but in case you didn’t notice, Harold was right in the middle of the best part of the story.”

“Wrong! The best part of the story is when Stuart goes down the bathtub drain on the string.”

“Einstein,” said Harold, “if you could please refrain from interrupting, that would—”

“The name is Einstein J. Treadupon!”

“As I said, please no more interrupting.”

Missy thought she detected an unusual note of exasperation in Harold’s voice. Once again she glanced at Mrs. Treadupon. This time she saw that Einstein’s mother was rubbing her forehead and frowning.

Missy touched her arm and whispered, “Is that your little boy?” She nodded toward Einstein.

“Yes. I’m so sorry. I do apologize.”

“He’s quite brilliant,” said Missy.

“A genius.”

“I imagine he’s hard to keep up with. He seems…” Missy trailed off, trying to find a nice way to say that Mrs. Treadupon’s son was a smarty-pants of the worst kind.

Before she could come up with something that wasn’t insulting, Mrs. Treadupon looked closely at her and whispered, “Oh, I beg your pardon. You’re Missy Piggle-Wiggle, aren’t you? Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s great-niece? I heard you’d moved here. You’re living in the upside-down house?”

“Yes.” Missy smiled at her.

“I’m Pandora Treadupon. Einstein J. Tread—I mean, Einstein is my youngest child.” She hesitated then whispered, “I’ve also heard that you have cures for children. Is that true?”

“Absolutely. Are you wondering if I might have a cure for Einstein?”

Pandora looked greatly relieved. She let out her breath. “Yes. Do you?”

“Right here in my purse,” said Missy, patting her handbag. Smarty-pantsiness was so common and so disruptive that Missy carried the cure around with her. It was incredibly helpful in emergencies such as this.

Pandora suddenly appeared nervous. “What exactly is the cure? Einstein is terribly smart, but he’s never learned to swallow pills.”

“Oh, the cure isn’t a pill.”

“He isn’t very cooperative about swallowing medicine, either.”

Missy rustled around in her handbag and withdrew a small green vial. It looked like a teeny, tiny bottle of ginger ale. “All I have to do is uncork this,” she whispered.

“That’s it?”

“That’s it. The rest will unfold on its own.”

Missy worked the cork out of the mouth of the bottle. Pandora watched in fascination as a bit of blue mist trailed upward, then picked up speed and made a beeline for Einstein. It settled around his head before vanishing.

Pandora craned her neck and peered at her son. “Really,” she said, “I don’t quite see how that’s going to accomplish anything.”

“Just wait.”

Mrs. Treadupon continued to stare at her son. He seemed occupied by a particular piece of paper in his briefcase.

In the front of the room, Harold came to the final sentence of the first chapter, read it, and said, “And that’s the end of chapter one.”

“Do you have to stop reading?” asked the girl at his feet, her voice quavering.

“Nope. We’ll go right on to the second chapter, which is called—”

Einstein suddenly came to life. He slammed the briefcase closed and shot to his feet. “‘Home Problems’!” he proclaimed. “It’s called ‘Home Problems’!”

“Oh, dear,” murmured Pandora.

“Patience,” whispered Missy.

“In my opinion, however,” Einstein continued, “what the chapter should be called…” He hesitated. “What it should be called,” he said again, and trailed off. He was finding it very difficult to speak. His voice was screeching and scratching like bicycle tires coming to a fast stop on a gravel road. “What it should be,” he croaked, and then he came to a complete stop. He put his hands to his throat.

Pandora started to get to her feet. “He’s choking!” she said.

“No, he’s fine,” Missy replied.

Einstein opened and closed his mouth several times. No sound came out.

“He looks like a salmon,” commented Tulip.

“Wait, now I can speak,” said Einstein suddenly. (Missy heard groans from all the adults and all the children.) “What I was going to say is that chickens cart around buckets from the ocean.”

Everyone stared at him.

Finally his brother said, “What?”

Einstein was frowning. “I said plain as day that the environment is riddled with snakes and telephones.”

Frankfort Freeforall, who was sitting next to Einstein, began to laugh and laughed so hard that he fell over on his side.

“Fun fact!” Einstein tried again, holding up his finger. “Cabinetry, I mean sophistry, I mean to say that time is getting away from all the rugs.”

“Goodness,” murmured Pandora.

Einstein coughed. Then, undaunted, he grabbed a pad of paper and a pencil from his briefcase. He began to write something, but Harold was reading again, and everyone became riveted to the story. No one paid any attention to the paper Einstein flashed around.

For a brief period of time, the only sound in the room was Harold’s voice. Then Einstein suddenly said, “Mice are … Miiiiiiice … aaaaaaare.” His voice screeched and squawked and faded away. His mouth flapped open and shut. He sighed then straightened his tie and smoothed out his gabardine suit pants.

The chapters in Stuart Little are not very long, so Harold read four of them before he gently closed the book and rested it on his lap. He glanced nervously down at the little girl by his feet, but she had fallen asleep. “I think this is a good stopping place,” said Harold quietly. He hesitated then went on. “Now is the time for questions and comments. Who has something to say about what I just read?”

Six children and one of the adults raised their hands.

Harold pointed to Melody. “Yes?”

“This is one of my favorite books,” said Melody shyly. “I’ve read it before, and each time—”

“I’VE READ IT, TOO!” cried Einstein. “The thing about reading any book more than once is that bunk beds are their fattest when the scanner isn’t working.”

Veronica Cupcake looked solemnly at Einstein. “You’re not making any sense. Do you need a nap?”

“I’m not tired,” Einstein replied crabbily. “I’m perfectly responsive to jelly rolls and what they mean.”

“See? See?” exclaimed Veronica. “He’s not making any sense, is he, Melody? Is he?” Veronica looked at Melody and then at the room in general.

“Why don’t you finish what you were going to say?” Harold suggested to Melody.

“Well, I was going to say that before I moved here, when I lived in the town of Utopia—”

“YOU KNOW,” said Einstein, “the term utopia is basically a foundation for pond water and flagpoles.” He leaned over to Frankfort and whispered, “Mr. Freeforall, did I just say ‘pond water and flagpoles’?”

“Yup.”

“Hmm.”

“If we could please have some discussion about Stuart Little,” said Harold, “that would be … refreshing. Melody?”

“I was just going to say that each time I read it, I feel like I’ve visited an old friend.”

“That’s lovely, Melody,” said Harold.

For several minutes, the children discussed the Little family and the fact that poor Stuart had gotten rolled up in a window shade and no one knew where he was. Finally Harold got to his feet. “Well, if there are no other comments, please join me at the back of the store for refreshments.”

Einstein hesitatingly raised his hand.

Harold sucked in his breath, but merely said, “Yes, Einstein? And thank you for raising your hand.”

“I think,” Einstein began slowly, “I think that it was very clever of Snowbell the cat to trick the Littles, even though what he did wasn’t nice.” He lowered his voice. “How did that sound, Mr. Freeforall?” he asked Frankfort.

“Normal.”

Einstein let out a sigh of relief.

* * *

In the car on the way home from A to Z Books, Marvel Treadupon Jr. had an idea. He stretched his legs out, crossed his ankles, crossed his arms, appeared to be thinking deeply, and finally said, “In school today, we learned that the planet Mercury—”

“FUN FACT!” trumpeted Einstein, sitting forward in the seat.

Marvel swiveled his head to observe his brother. He was hoping to see him turn into a salmon again. He wasn’t disappointed. Einstein’s voice took on the screeching quality, faltered, and finally disappeared altogether.

Marvel hooted with laughter, slapping his hand on the seat. “Einstein is gulping like a fish!”

“Goodness,” said Pandora.

“My name is Einstein J. Beagle!” Einstein said, finding his voice. “And picture mints are definitely scarring to the eyebrows.”

Marvel hooted more loudly. “Einstein J. Beagle!”

Pandora looked at her older son in the rearview mirror. “Dear, what were you going to tell us about Mercury?”

“I was going to say that Mercury doesn’t have any moons, and the only other planet that doesn’t have any moons is…” Marvel glanced sideways at his brother, but Einstein sat patiently. “The only other one is Venus,” Marvel finished at last. He had hoped to hear Einstein J. Beagle talk about pond water and bunk beds again.

Instead Einstein asked, “What about Pluto?”

“What about Pluto?”

“Well, it’s considered a dwarf planet, not a regular one, so I didn’t know if you were studying it.”

“We are studying it,” said Marvel, “and it does have moons.”

“Interesting,” replied Einstein.

* * *

Later that afternoon, Tallulah said, “Mother, Father, do you think we could have hors d’oeuvres before dinner this evening? We could pretend we’re having a fancy party.”

“What a lovely idea,” replied Pandora, and she and Marvel Senior set about preparing a tray of vegetable sticks and teeny, tiny hot dogs with toothpicks in them.

When everything was ready, Pandora said, “Let’s sit down. We’ll have the hors d’oeuvres in the living room.”

“Très bien, Maman,” replied Einstein.

Tallulah, who had put on her fanciest dress and a small amount of lipstick in honor of the hors d’oeuvres, leaned forward to take a hot dog and said, “In math class today, Benedict told us that the most interesting prime number is two.”

“Wrong!” roared Einstein. He bit the end off a carrot stick. “Everyone knows it’s seventy-three.”

Pandora studied her son. When he didn’t elaborate on his answer, she said to Marvel Senior, “I got an e-mail today about a lecture on hummingbirds. It’s going to be held next Saturday.”

“SATURDAY,” Einstein yelled, “IS NAMED FOR THE PLANET SATURN, and Saturn has sixty-two moons, which…”

Tallulah and Marvel Junior nudged each other as their brother’s voice croaked to a stop and he said, “The cabbages from Portland … I mean, um … La voilà le chien qui parle et le voisin du…”

Mr. Treadupon turned to his wife in alarm, but she rested a reassuring hand on his shoulder. “Tallulah, dear,” she said, “tell everyone your news about glee club.”

Tallulah dabbed at her lipstick with a cocktail napkin. “We’re going to have one more performance before school is over.”

In the silence that followed, Einstein asked timidly, “When will it take place?”

“In two weeks. We’re putting on a show at night, and we’re charging admission, and all the money will be donated to the firehouse. The firehouse,” she said, looking at Einstein. “The one your class will be visiting.”

“Well, that’s very nice of you,” Einstein replied. “I’ll be sure to mention it to Mr. Graham.”

* * *

Einstein didn’t interrupt anyone else during dinner that evening. After the children were in bed, Marvel Senior turned wonderingly to his wife and said, “What on earth has come over Einstein?”

Pandora thought about telling him of the adventure at the bookstore, but she found that she was all talked out. “Maybe he’s growing up,” she replied simply.

“Well, it certainly is a pleasant change.”

Upstairs, Einstein lay in his bed, his hands behind his head, and thought about all he had learned that night. He thought about his sister’s concert and a project that Marvel Junior would soon be entering in the school science fair.

Just before he had closed his door, he’d called, “Good night, Ms. Treadupon, Mr. Treadupon!”

“Good night,” his sister and brother had replied. Tallulah had added, “It was nice talking to you.”

It had been nice, Einstein thought. He had never realized that his brother liked science as much as Einstein himself did, and he had learned that Tallulah was the lead alto in the glee club, but that she was more interested in raising money for the firehouse than in perfecting her solo. Furthermore, he had accumulated some extremely interesting facts that afternoon, just by listening when other people spoke.

* * *

Early the next morning, the phone rang in the Treadupon house. Pandora, who had been enjoying a nice peaceful cup of tea, answered it.

“Mrs. Treadupon?” said the voice on the other end. “This is Missy Piggle-Wiggle. I was just wondering how things were going. Do you think you’ll need another dose of the cure for Einstein?”

“I don’t believe I will,” Pandora replied. “Thank you so much, Missy. You’re a miracle worker.”