WAREFORD MONTPELIER’S FIRST bad day took place shortly before summer vacation began. It started the moment he woke up one morning. He rolled out of bed and sleepily walked into the wall. He let out a yelp. Huh, thought Wareford. I got up on the wrong side of the bed. This had never happened to him before. Wareford brushed his teeth and dressed for school. On his way to breakfast, he tripped on the stairs and fell down the last three steps.

“Wary?” called his father from the kitchen. “Are you all right?”

Wareford was sitting on his bottom by an armchair. “I guess so,” he said. He rubbed his hip. Then he walked to the breakfast table, plopped down on his chair, and slipped off the other side. He landed on his bottom again.

“What is wrong with you?” asked Charlemagne. Charlemagne was Wary’s sister. She was fourteen years old and embarrassed by everything Wary did, even if she was the only one there to see it.

“Charlemagne! Have a bit of sympathy for your brother,” said Mrs. Montpelier. She helped her son back onto his chair.

“Well,” said Wareford. “At least it’s over now.”

“What’s over?” asked his father.

“My streak of bad luck. Three bad things happened. I walked into the wall, I fell down the stairs, and I fell out of my chair. That should be the end of the streak. Bad things happen in threes.”

“Maybe,” said his sister, “this was just the first of three groups of three bad things. Maybe six more bad things will happen to you today.” Charlemagne drew comfort from the fact that since she was fourteen and Wary was ten, they went to different schools and rode different buses. She wouldn’t be anywhere near Wary if six more embarrassingly bad things should happen to him.

“Charlemagne, for heaven’s sake!” exclaimed her mother.

“Oh, I’m okay,” said Wary confidently, and then he bit his tongue.

It began to bleed.

“Ew! Disgusting!” cried Charlemagne. She grabbed her backpack and ran out the front door.

Mr. and Mrs. Montpelier got Wary some ice and gauze. When the bleeding had stopped, he grabbed his own backpack. “Thee you after thcool,” he lisped. He walked out the door more slowly than usual, eyes peeled for anything he might trip over. Ten minutes later, he reached the bus stop. He was the only one there. Three blocks away, his bus was turning a corner, heading for the next stop.

Wary slowly made his way home again. “I mithed the buth,” he announced.

“Oh, dear,” said his mother. “Well, don’t worry. I’ll drop you off on my way to work.”

* * *

Before Wary even reached his classroom that day, he got locked in the boys’ bathroom. He had stepped inside to examine his tongue in the mirror. When he was satisfied that the bleeding had truly stopped, he picked up his backpack and tugged at the handle of the door. He tugged and tugged and tugged. Yikes! he thought. I’m locked in the bathroom. This had never happened before, either.

“Hello?” he called.

Nothing.

“Hello? HELLO?!”

He put his ear to the door and listened, but because he had arrived at school late, the halls were quiet—everyone was already in class.

Wary tugged at the handle again. He tried pushing at the door, just in case he had forgotten how it worked. He shoved against it with all his might. Then he grabbed the handle and pulled with all his might.

More nothing.

Wary had opened his mouth to scream “SOMEBODY GET ME OUT OF HERE!” when he heard knocking on the other side of the door.

“Is somebody stuck in there?”

Wary recognized the voice of Mr. Samsonite, the maintenance man. He drooped with relief. “Yes! It’s me, Wareford Montpelier. Get me out! I mean, please get me out!”

It took a crowbar, half an hour, and two people from the maintenance crew, but at last Wary was free. He should have been relieved, but all he could think about was what Charlemagne had said: that nine bad things might happen to him that day. He was up to only number six. Three more to go.

* * *

When Wary returned from his long bad day at school, he slumped into Charlemagne’s bedroom and let out a moan. “You were wrong.”

Charlemagne crossed her arms and glared at him. “About what?”

“You said three groups of three bad things were going to happen to me today. That’s nine. And I’m already up to number eleven.”

Wary thought he saw his sister’s face soften. “Really? Eleven bad things?” she said.

“Yes. After I bit my tongue, I missed the bus, got locked in the bathroom, got thirty-eight percent on a surprise math quiz, got picked last for kickball, lost my hat, tripped over a tree root, and re-bit my tongue.” Wary looked at his watch. “And it’s only four o’clock.”

“I’m sorry,” said Charlemagne.

At bedtime that night, Mr. Montpelier sat next to his son and patted his arm while Wary again listed the bad things, which now numbered fourteen.

“It was just a rotten day,” said his father.

His mother stepped into the room and handed him a chocolate candy. “Tomorrow is bound to be better,” she added.

“How about if I read you a chapter of Lassie?” asked his father.

Wary looked listlessly at his parents while he unwrapped the chocolate. “Thanks,” he said.

* * *

When Wary awoke the next morning, he found that he felt rather hopeful. He lay in his bed for a few moments, thinking about the previous day. Finally, he said aloud, “How could today be any worse?” He sat up slowly and swung his legs over the nonwall side of the bed.

He got dressed without incident.

He made his way to the doorway of the kitchen without incident.

And then Shady, the Montpeliers’ cat, pounced on his feet from under the table, and Wary tripped, fell into Shady’s water bowl, hit his head on a cabinet door as he stood up, fell down again, knocked his glasses to the floor, and closed his hand over a spider as he groped for the glasses.

“Aughhhhhhh!” he screamed.

Charlemagne regarded her brother with awe. “He’s like all Three Stooges rolled into one,” she said.

“How can this be happening?” asked Wary. He found his glasses, washed the hand that had touched the spider, and mopped up the spilled water. Then he felt the top of his head. “I’m bleeding,” he announced. “Again.”

“Gross!” exclaimed Charlemagne and fled from the house.

Mrs. Montpelier handed Wary a tissue. Then she tossed something into his lunch bag. “A little extra treat.” She smiled at him.

Mr. Montpelier said, “Why don’t I drive you to school today?”

“Thank you. That’s a good idea,” said Wary. “Because if I took the bus, I’d probably trip in the aisle, no one would want to sit with me, I’d get bus-sick—”

“You’ve never in your life gotten bus-sick, dear,” said his mother.

“I’ve never fallen in a water bowl, either.” Wary lowered himself cautiously onto his chair. “Also,” he continued, “the bus would probably get a flat tire—”

“Well, you don’t need to worry about those things, since I’m going to drive you,” his father pointed out.

* * *

When Wary returned from school that afternoon, he found Charlemagne and her friend Desiree sitting side by side on the front steps.

“Here he is!” Charlemagne exclaimed. “Wary, how many bad things happened to you today?”

Wareford melted onto the bottom step and put his head in his hands. “Twelve. So far,” he muttered. “And I’m counting the water bowl and the spider and the bleeding head as all one thing.”

“See?” Charlemagne said to Desiree. “What did I tell you?”

Wareford was feeling too sorry for himself to care that his sister sounded proud of him. After a few moments, he realized that Desiree had leaned down and was staring at him.

“Is your nose bleeding?” she asked.

“A little. I fell onto Georgie Pepperpot’s elbow.”

There was silence, and finally Charlemagne said, “Wary, don’t you want to go inside and put your things away?”

He sighed. “You’d better help me up the steps. I might fall.”

Charlemagne didn’t bother to point out that Wary could hold on to the railing. She took her brother gently by the elbow and guided him all the way into the kitchen. Desiree joined them, and the girls fixed Wary a snack. When he finished it, he sat where he was and did his homework, figuring it was best not to move around too much. He didn’t leave his chair until bedtime.

* * *

The next morning, which was Saturday, Wary slept late and went downstairs in his pajamas. He spent two hours curled up on the couch under a blanket.

“Are you sick?” Charlemagne asked him.

“No,” replied Wary, eyes downcast.

“Don’t you want to play outside?” said his mother. “It’s a beautiful day.”

Wary ignored the question. “Are you going to the store this morning?” he asked.

“Yes. Why?”

“You’d better stock up on Band-Aids and first-aid cream.” As his mother left the house, Wary called after her, “Drive carefully,” but his voice was so weak, she didn’t hear him.

* * *

It didn’t take long for Charlemagne to tire of her brother’s behavior.

“At first I thought he was cute,” said Charlemagne, “but now he’s just like, ‘Wah-wah-wah. Look at all the bad things that happen to me.’”

Mrs. Montpelier shook her head. “He barely leaves the house, and it’s summer vacation.”

“What should we do?” asked Mr. Montpelier.

Nobody knew. They had never encountered behavior like Wary’s before.

At lunchtime that day, Georgie Pepperpot rang the Montpeliers’ bell. “Let’s go ride our bikes!” he said to Wary.

“I’d better not. I might fall off.”

That afternoon, Rusty Goodenough stopped by. “Wary, come with me to watch the Little League game. Linden is playing.”

“I’d better not. I might get hit in the head with a ball.”

After Wary and Charlemagne had gone to bed that night, their parents sat on the front porch in the warm July air.

Mrs. Montpelier let out a sigh. “Isn’t this wonderful?” she said. “A perfect summer evening. I love summer. Just think, a month from now we’ll be at the beach. Two whole weeks at the shore.”

Her husband cleared his throat. “Well…”

“Uh-oh. What?”

“I mentioned the beach to Wary this evening—you know, trying to give him something to look forward to—and what do you think he said? He said, ‘The beach doesn’t sound very safe, Dad. Maybe we shouldn’t go. There could be a tidal wave. What if I get washed away by a tidal wave? Or I could get bitten by a shark or step on a broken seashell with my bare feet or stay out in the sun too long.’”

Mr. Montpelier turned to his wife. “Oh, dear,” she said. But then she began to smile. “I think I know how to make him feel better. I’ll point out how unlikely all these things are. The tidal wave, for instance. Do you think there has ever been a tidal wave at the Jersey Shore? I’ll talk to him tomorrow. I’ll let him know there’s really nothing to be afraid of.”

Wary’s mother couldn’t wait to present him with a few facts. The moment he got up the next morning, she said to him, “Wary, I understand you have some concerns about our vacation in Avalon. Do you know that I was doing some research about tidal waves”—(This was a lie. Wary’s mother hadn’t so much as googled “tidal waves.”)—“and there has never, ever been a tidal wave at—”

Wary interrupted his mother. “Don’t you always tell Charlemagne and me that there’s a first time for everything?”

“Yes.…”

“For instance, falling in Shady’s water bowl?”

“Well…”

“Since I’m a bad-luck magnet, I could easily attract the first tidal wave to New Jersey. And you don’t want us to get swept away, do you?”

“Of course not, but … but…” Mrs. Montpelier couldn’t even figure out how to finish her sentence.

Mr. Montpelier tried a different approach. “You know, Wary,” he said that afternoon. They were in the garage. Wary had agreed to toss a ball with his father, but only if they played with a foam ball. Also, just in case he fell down, Wary had put on elbow pads, kneepads, and a football helmet. “Some things can’t be avoided,” his father continued.

“What things can’t be avoided?”

“The sun, for instance.”

“That’s why the beach isn’t a good idea. It’s also why we’re playing catch in the garage.”

Mr. Montpelier put his arm around Wary. “But you don’t want to sit in the house all day when we go to Avalon, do you? That wouldn’t be any fun.”

“Oh, staying indoors wouldn’t solve anything,” said Wary. “The tidal wave could still get me.”

Mr. Montpelier went inside and found his wife. “We have a distinct problem,” he whispered to her.

* * *

Across Little Spring Valley, the yard at Missy Piggle-Wiggle’s was a busy place. Fourteen children, many of them friends of Wary’s, were jumping rope, climbing trees, and looking for treasure. Three children had dressed themselves in clothes from Missy’s costume box and were playing Rock Band. Tulip Goodenough and Samantha Tickle were sitting in the grass by a garden weaving daisy chains.

Melody sat alone on the front porch, watching Tulip and Samantha. She had asked if she could join them, and Samantha had replied, “Why? So you can tell us how they make daisy chains in Utopia? Maybe our way is better.”

So now Melody sat on the top step, chin in her hands. She didn’t even look at Lester when he settled down beside her. After a long time, he placed one front hoof on her hand and patted her gently. Even though this felt like being patted by a coconut, Melody offered him a small smile.

A few minutes later, Missy joined them on the porch. She sat on the swing, and as she swayed back and forth, her lavender dress shimmered and wafted around her legs. She looked from Melody and Lester to Tulip and Samantha, but all she said was, “I haven’t seen Wareford Montpelier in quite some time. Is his family away on vacation?”

“I don’t think so,” replied Melody.

From the flower garden, Tulip called, “He doesn’t leave his house anymore! Rusty told me so.”

Samantha nudged her friend and said in a whisper loud enough for everyone on the porch to hear, “Don’t say that! Melody will blame it on Little Spring Valley.”

Missy considered what she had heard. Her eyes narrowed slightly, and you would have had to look into them very closely to see that they were glittering. At the same time, for the briefest moment, her hair sprang up as if electrified. Then it settled back onto her shoulders, and she said comfortably, “Why isn’t Wary leaving his house?”

“Afraid,” said Samantha.

“Afraid of what?” Melody dared to ask.

“Everything,” said Tulip.

Missy left the porch and climbed the stairs to her bedroom. Today the house had floated all the rugs up to the ceilings, so Missy clumped along noisily on the bare floors, sending up a little puff of dust with each step. She waved to Serena, who was wrestling with a radiator in Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s bedroom, and then she went into her own room, unlocked the potion cabinet, and surveyed the bottles and jars and packets inside. She saw that three had worked their way to the front of the shelves: the Don’t-Want-to-Try Cure, the I-Can’t Cure, and a general Fear-All Cure.

“Thank you,” Missy said to the cabinet. “I don’t know yet if I’ll need any of you, but my fingertips are telling me I’ll be getting a phone call very soon.”

The call came shortly after seven that evening. Wareford’s father was on the other end of the line. “We’ve never experienced anything like this!” he exclaimed to Missy. “Not with Charlemagne, and not with Wary until—”

“Until he had a bad day?” suggested Missy.

“Exactly. But it wasn’t just one day. He had a streak of bad luck. It went on for quite a while.”

“It’s natural to want to coddle a child during a time like that.”

Wary’s father frowned at the phone. “We didn’t exactly coddle him,” he said, even as he thought about chocolate candies and rides to school and the mornings Wary was allowed to spend lying on the couch. How on earth did Missy Piggle-Wiggle know what had gone on during the past few weeks?

“In any case, Wareford needs to feel safe again,” said Missy.

“Yes,” replied Mr. Montpelier. “And he needs to feel in control again.”

“Exactly. I wonder if you could spare Wary for a day or so. Could he come stay with me at the upside-down house?”

Mr. Montpelier pretended to think this over. “Goodness,” he said at last. “Part with Wareford for several days? I don’t know. I’ll have to check with my wife. I’ll get back to you later this evening.”

Wareford’s father was aware that Missy was as magical as her great-aunt, so he hoped she couldn’t somehow see that as soon as he clicked off the phone, he picked up Shady and danced her around the kitchen, then poked his head out the back door and shouted, “Yahoo!” into the twilight. After that, he ran through the house to the living room. “Dear! Dear!” he called to his wife with great excitement. Then he lowered his voice. “Where’s Wary?”

“Upstairs. Still finishing his dinner in bed. He’s having a particularly difficult day, poor lamb.”

“Guess what Missy said,” Mr. Montpelier whispered. He told his wife that they were going to have a little break from Wareford.

“I wonder what Missy plans to do with him?” said Mrs. Montpelier, frowning. “I hope it isn’t too drastic. Wary is more nervous every day.”

“All I know is that he’s going to come home cured.”

It was Wary’s mother who called Missy back later. “What should we pack for him?” she asked. “Is there a fee involved? Can we bring him tonight?”

“First thing tomorrow morning will be fine,” Missy said crisply. “I need to get his room ready.”

* * *

In truth, all it took was a snap of Missy’s fingers to transform the guest room into a sanctuary for Wareford Montpelier. She stood at the door, raised her hand, and snap! A small green tornado whisked itself into shape and whirled through the room, sweeping away the bed with its dust ruffle and spread, the dresser with its cheerful rose-colored knobs, the table with its stack of storybooks, and the child-size desk and chair. Left in its wake was the perfect environment in which to put into effect the Woe-Is-Me Cure.

Missy looked at the room with satisfaction and then hurried downstairs. “Lester, Penelope, Wag, Lightfoot,” she said. “We’re going to have company for a couple of days. I expect you to be on your best behavior.”

Lester bowed. Penelope cocked her head and squawked, “Just what I was hoping for—more people in the house!” Wag wagged his tail. Lightfoot turned her back and edged out of the room.

“House?” said Missy. “Will you behave, too? We have work to do.”

The house dumped all the rugs back down to the floors.

“Thank you,” said Missy.

* * *

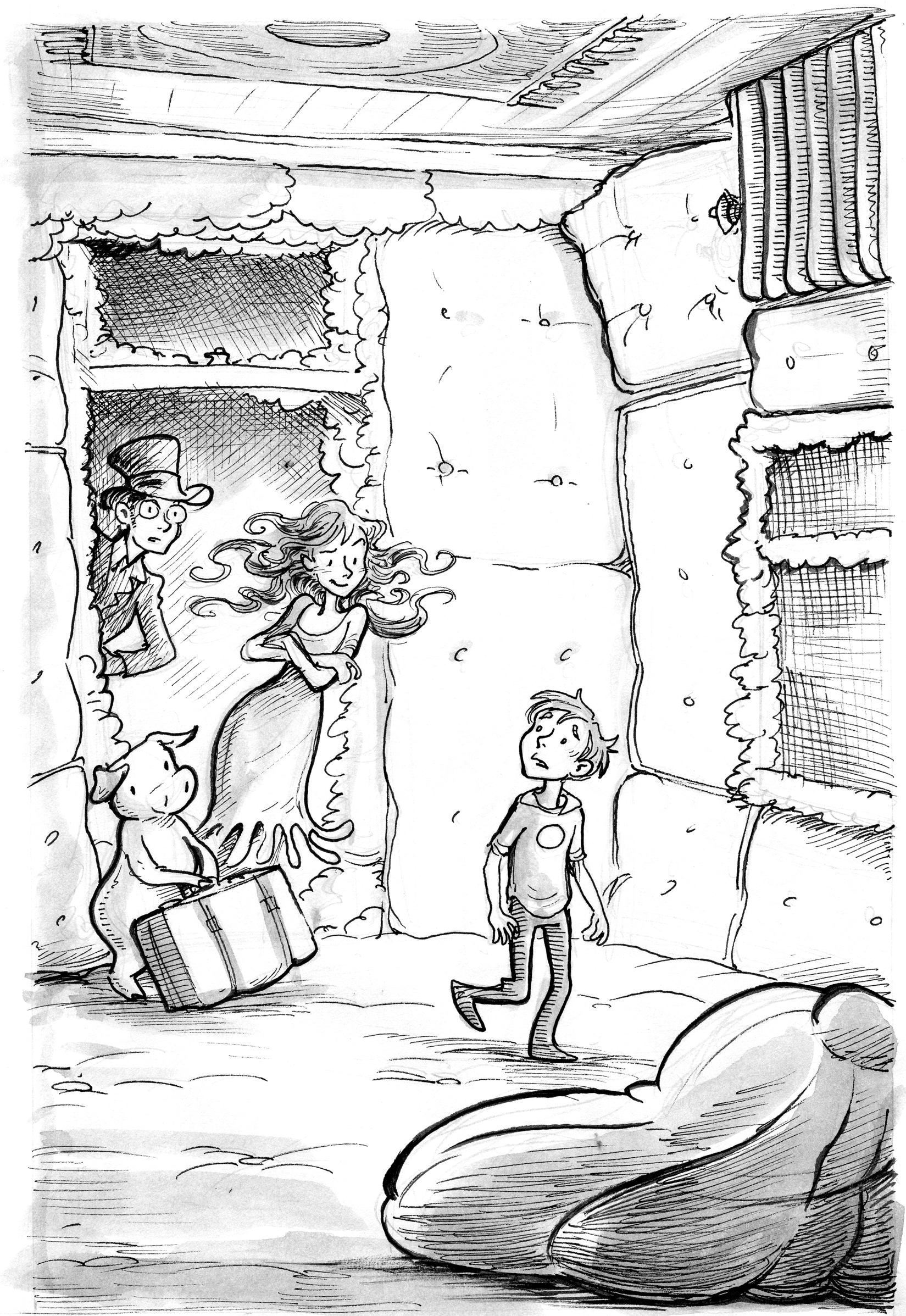

The next morning, Harold stopped at the upside-down house on his way to work to check on the progress of the repairs. He and Missy were chatting with Serena, who was saying, “I think that at last we’re nearly done,” when the Montpeliers arrived. The entire family had come to see Wary off. Mr. and Mrs. Montpelier sprang out of the front seat. Charlemagne tried to open her door, found it locked, and, in her excitement, thrust herself through the open window. “Come on, Wary!” she called to her brother. She reached back through the window and yanked at his wrist.

Wary slowly unbuckled his seat belt. Then he unlocked the door, opened it cautiously, and looked up and down the sidewalk to make sure he wouldn’t get run over by a tricycle or a scooter.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Montpelier had opened the trunk, removed Wary’s suitcase, and carried it across the yard. She waited while her son crept along the walk to Missy’s porch. “Remember your manners,” she said, stooping to Wary’s level and resting her hand on his cheek. Then she pulled him close for a hug.

“Thank you so much, Missy,” said her husband, and he hugged Wary, too, before dashing back to the car.

“Yes, thank you!” added Charlemagne.

The Montpeliers sped off down the street.

Harold frowned after them. “They practically left tire marks on the road,” he whispered to Missy.

“I’m afraid this is a rather extreme case.”

“An extreme case of what?”

“Woe-Is-Me Syndrome.”

“Hmm.”

Missy looked at Wary, who was sitting at the very edge of a porch chair in case he needed to make a quick getaway from a bee. “I understand you’ve been having a bit of a hard time,” she said to him gently.

Wary nodded, and tears filled his eyes. “Bad things just keep happening to me. One after another.”

“Well, I have the perfect solution for you.” Missy held out her hand. “Come with me. I’ll show you to the guest room.”

Wary had stayed in the guest room at his grandfather’s house many times. There was a bed in it with four tall posts and a pale-blue canopy draped across the top. There was a dresser in which he could put his clothes, but the bottom drawer of the dresser was full of things that had belonged to his mother when she was a little girl. Wary liked to take them out and examine them: a seashell, a pin from the Girl Scouts, photos, awards. Plus there was a cupboard full of toys and games that his grandfather had bought brand-new, just for Wary and Charlemagne.

So you can imagine Wary’s surprise when Missy opened the door to the guest room at the upside-down house and he saw nothing but padding. The floor, the walls, and even the ceiling were covered with what looked like mattresses. The windows were edged with giant cotton balls, and the panes of glass had been removed and replaced with screens.

Wary was speechless. He glanced behind him into the hall where Missy stood, smiling. Next to her was Lester, the polite pig who had helpfully carried Wary’s suitcase up the stairs, and next to him was Harold Spectacle from the bookstore, wearing an astonished expression. The expression was mirrored on Serena’s face when she passed by the guest room.

“Did you want me to do some repairs in here, too?” she asked just as Wary said, “This is the guest room?” He thought Missy must have mistakenly opened the door to a storage room.

Missy said, “No, thank you,” to Serena, and, “Yes, it’s all yours,” to Wareford.

“But where do I sleep?” asked Wary.

“Why, right there on the floor. It’s nice and soft and cushiony. Impossible for you to get hurt.”

“What am I supposed to do in here?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well…” Wary didn’t want to be an impolite guest. “Could I have a TV?”

“Heavens, no. You might run into it. Or it might topple over on you.”

Wary nodded thoughtfully. “That’s true. Then how about a pad of paper and a pencil?”

“A pencil? Out of the question. You could jab yourself with it,” said Missy. “Maybe I’ll give you a crayon. Just don’t accidentally swallow it.”

Wary stepped into the room and stood on the padding. He turned around and around. “Should I take off my shoes?”

“Good idea. I see that yours have laces. Laces can be very dangerous indeed.” Missy held out her hand for the sneakers.

“Oh, I know all about laces,” said Wary. “I’ve already tripped over them twice. Mom wouldn’t let me get new shoes, though.”

Enough dilly-dallying, thought Missy. She blinked her eyes. She blinked them four times, but she did it so fast that all anyone saw was one blink—and then Penelope screeched from her perch on the banister, “It’s nine thirty, Harold Spectacle!”

Harold snapped to attention. “Time for me to get to the store,” he exclaimed.

“Time for me to get back to work,” said Serena.

Wary turned warily around in his new room.

* * *

Wareford’s first day at Missy’s seemed a bit long, but he didn’t want to be rude and complain. For a while, he simply sat on the padded floor. When he heard shouts from outside, he got to his feet and bounced his way across the padding to the window, grateful not to have to worry about tripping over anything. He leaned on the cotton balls and looked at the yard below. He saw Rusty and Tulip teaching Veronica Cupcake how to hit a softball. After two misses, her bat connected with the ball—thwack!—and the ball soared across the yard.

“Home run!” shouted Tulip.

In his room, Wary ducked and plopped down on the mattress. “That was close,” he said to Wag, who was peeking at him from the hallway. But soon, because there was absolutely nothing else to do, Wary found himself looking out the window again. This time he saw Veronica hit a ball, toss her bat to the ground, trip over it, and skin her knee.

“Ow!” she cried. But then she brightened. “Hey, now Missy will give me a Band-Aid.”

“Hmm,” said Wary from his padded room.

Down below, Linden Pettigrew yanked Missy’s garden hose around to a pot of begonias, turned the water on, and managed to spray himself from head to toe before unsticking the nozzle. “Ha!” he hooted. “That’s the third time I’ve done that this week. Oh, well.”

“Interesting,” murmured Wareford.

An hour passed, and then another.

“Missy?” called Wary.

Missy appeared instantly.

“I thought you were outside,” said Wary, who had just seen her handing a volleyball to Tulip.

“Hmm. Well, was there something you wanted?”

Wary peered over Missy’s shoulder. How had she climbed the stairs so quickly—and so quietly? “I was wondering about the paper and … crayon.” Wary hadn’t used a crayon in three years.

“Certainly,” said Missy, and from nowhere a red satchel appeared on her shoulder. She opened it and produced a blue crayon and several sheets of paper. “Here you go. Now I’d better see about some lunch for you.”

In the guest room of the upside-down house, Wary sat on the floor and tried to draw a picture. Every time he pressed the crayon to a piece of paper, the paper sank into the mattress, forming a soft crater.

Downstairs in the kitchen, Missy looked through her cupboards, which were nearly bare. I really must search for the silver key, she thought. But not today. Today I must concentrate on Wareford. She set out a tray, and on it she placed a plastic cup of applesauce, a plastic cup of cold soup, and a paper plate holding a piece of buttered bread. Next to the plate, she placed a plastic spoon. Nothing breakable, nothing sharp, and nothing Wary could choke on or burn his tongue with.

“Lunchtime!” announced Missy. She stood outside Wary’s room and looked in at a sea of crumpled papers, each decorated by a few faint blue marks.

“Oh, good,” replied Wareford, brushing aside the papers.

Missy left the tray in the hall and carried the food to her guest. She set the plate and cups on the floor and handed Wary the spoon.

“Um…” said Wary.

“Oh, of course. You’ll need something to eat on.”

Missy hurried away and returned with a puffy pillow. “Just set this on your lap and use it like a table.”

“Thank you,” said Wary politely. “This is all very”—he paused—“very soft.”

“And very safe.”

* * *

At bedtime that evening, Missy brought several blankets and another pillow into the guest room. She arranged them in the middle of the floor. “Sleep well,” she said.

Harold Spectacle had arrived for another game of Scrabble with Missy and Lester, and he watched from the doorway. He was wearing a red-and-green striped vest and dark-green pants that billowed out from his waist and seemed to have many, many pockets. A watch on a chain looped from one pocket to another. Wary wondered what was in the others.

“If you don’t mind my asking,” said Harold, “why is Wareford sleeping in the middle of the room? Wouldn’t a corner be cozier?”

“He has a habit of waking up and walking into walls,” replied Missy.

“It’s not exactly a habit,” said Wary. “I only did that once.”

“You can’t be too careful, though.”

“I suppose not.”

Harold suddenly looked as though he felt sorry for Wary. “Would you like me to read to you for a while?” he asked.

“Yes, please,” replied Wary, who was wondering how he was going to sleep in this strange room with no curtains at the window and the moon shining brightly.

Harold found a copy of The Twenty-One Balloons and carried it into the guest room.

“Wait!” cried Missy. She held up her hands. “Sit out here in the hall. It’s much safer for Wary.”

“But that’s a paperback book,” said Wary.

“Still,” replied Missy.

So Harold sat in the doorway of Wary’s room and began the story about the incredible adventure of Professor Sherman.

“A wise choice,” Missy whispered to Harold.

“Thank you.”

* * *

Somehow Wary managed to fall asleep in his padded, protected room at the upside-down house. The next morning, he wobbled across the mattresses to the door and flung it open, ready to call good morning to Missy. To his surprise, he found her standing in the hallway. She was holding a breakfast tray with an array of very soft foods.

“Hello, Wary,” she said. “I have a nice runny egg for you and some yogurt and another cup of applesauce.”

“Thank you,” Wary replied. “But, before I eat, could we talk?”

“Of course.” Missy’s eyes glittered as she left the tray in the hall and joined Wary on the floor. “What would you like to talk about?”

“Me.” Wary thought for a moment. “And Professor Sherman.”

“Professor Sherman from the book?”

“Yes. I was thinking about how brave he was. And about how he set out to do one thing, and then got caught up in something else and had a wonderful adventure in Krakatoa.”

“That’s the magic of books,” said Missy. “You can read about all sorts of things.”

“But I kind of miss actually doing things. Nothing is ever going to happen to me if I just lie around my house.”

“Then how are you going to avoid tripping and falling and—”

“And getting whacked with a softball and stepping on a seashell? I guess I can’t. Not if I want to play outdoors with my friends and go on vacation with my family.”

“Or fly to Krakatoa,” said Missy.

Wareford nodded. “Anyway, I’m in charge of me, and I can decide whether I want to laugh or cry when I spray myself with the garden hose. Do you understand what I mean?”

“Perfectly.”

Wary waded across the padding to the window and looked outside. “Linden and Beaufort are already here,” he said.

“Do you want to join them?” asked Missy.

Wary thought about another day of mattresses and applesauce. “Yes,” he said, “but first I want to talk to my parents.”

Missy handed Wary the phone, and he called his family and told them he was coming home.