3

Corrective Discipline

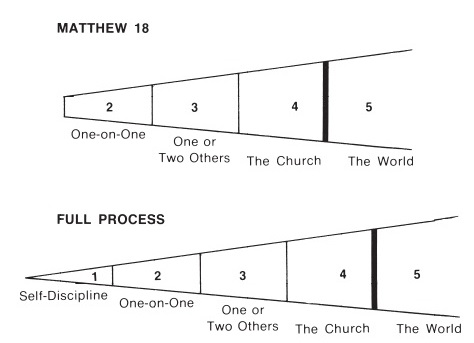

There are five steps in corrective discipline. They may best be understood by careful study of this diagram:

You will notice that the first three steps are informal and do not involve official action by the organized church, but pertain solely to the activities of individual members acting on their own initiative in obedience to Christ’s commands. The fourth and the fifth involve the church as an official organization. Moreover, during the first four the offender is regarded as a Christian, but during the fifth he is regarded as an unbeliever.

You will also notice that as discipline progresses from one step to the next, the number of persons participating enlarges (as indicated by the widening of the lines in the diagram), moving from one individual disciplining himself, to a one-on-one confrontation, to calling in one or two others to help, to the assistance of the local church and, finally, to exposure to the world. Each of these factors is of importance and must be explained and elucidated in turn. In the rest of the book I shall do just that, but in this chapter I shall take the time to look at the process as a whole.

In Matthew 18:15-17, Jesus sets forth in clear terms four steps of discipline. Why then are there five steps in the diagram? Because there is an additional step—not dealt with by Jesus in that passage, since it was of no concern to Him at the moment, yet mentioned elsewhere in the Scriptures—that is of such great importance that it is the point from which all discipline initially flows and to which all of the rest of the steps or stages in discipline ultimately point.

Therefore, I have added in front of the four steps of Matthew 18 a step called “self-discipline.” This matter does not arise in Jesus’ list of steps, since He is concerned about what to do when there is a matter between brothers (v. 18). He starts one step further along the line. Here is what He said:

If your brother sins against you, go and convict him of his sin privately, with just the two of you present. If he listens to you, you have won your brother.

But if he won’t listen to you, take with you one or two others so that by the mouth of two or three witnesses every word may be confirmed.

And if he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church. And if he refuses to listen to the church, treat him as a heathen and a tax collector.

(Matthew 18:15-17)

As you can see, Jesus’ interest does not extend backward to the struggle in the offender before he commits the offense. But in our diagram, to be complete we must also consider the matter of self-discipline. I wish to thank the Rev. Roger Wagner for first calling my attention to this matter.

Self-discipline (egkrateia) is mentioned in Galatians 5:23 as part of the Spirit’s fruit. It is only when one fails to exercise self-discipline that the process set forth in Matthew 18 comes into play. But it is also important to realize that whenever there is success reconciling parties at any subsequent stage—one-on-one, one or two others, etc.—such success is incomplete if it does not go beyond the issue of the moment to deal with the offender’s problem preventively in terms of self-discipline. That is to say, the party who failed to exercise self-control also must be helped, usually by counseling, so that in the future he will be able to face similar situations without losing self-control.

The process in our diagram and the process in Matthew 18:15, when compared, look like this:

Several matters must concern us in a preliminary way. To begin with, take the ever-enlarging numbers of persons involved in the ongoing process of church discipline: first one, then two, then three or four, then the entire church, and finally the world. The implication of this biblical requirement to seek additional help in order to reclaim an offender is that Christians must never promise absolute confidentiality to any person. Frequently it is the practice of Bible-believing Christians to give assurances of absolute confidentiality, never realizing that they are following a policy that originated in the Middle Ages and that is unbiblical and contrary to Scripture (there is not a scrap of evidence in the Bible for the practice).

Both individuals and counselors must be aware of the all-important fact that absolute confidentiality prohibits the proper exercise of church discipline. If, for example, in step 2, which involves a one-on-one confrontation, one party asks the other for absolute confidentiality as a prerequisite to reconciliation, he thereby makes it impossible for the second party to move to step 3 (or beyond) in the process of church discipline, should negotiations fail at step 2. Or, when another party is called in to give counsel at stage three, if the original parties demand absolute confidentiality of this counselor they make it impossible for him to move the process to steps 4 and 5 should they be necessary. Nor could the “two or three others” function as “witnesses” as Jesus required. In other words, because absolute confidentiality is an unbiblical concept, it serves only to keep persons who need the help of others from receiving it.

Of even greater importance than the matter of hindering the process of discipline and thereby depriving those parties involved of the assistance they need, including the help of Christ working formally through His church, is the fact that absolute confidentiality requires one to make a hasty vow. No such vow to silence should ever be made. A rash vow of this sort may put us in a bind where we are obligated to God to move the process of discipline on to a larger sphere, yet our vow to silence prohibits us from doing so. We must never put ourselves in a position where we find it impossible to obey a biblical commandment because of a vow we have made. No vow must ever involve possible disobedience to God; the vow of absolute confidentiality always does.

Is it right, then, to refuse to grant any confidentiality at all? No, confidentiality is assumed in the gradual widening of the sphere of concern to other persons set forth in Matthew 18:15ff. As you read the words of our Lord in that passage, you get the impression that it is only reluctantly, when all else fails, that more and more persons may be called in, The ideal seems to be to keep the matter as narrow as possible. When Jesus speaks of step 2 (one-on-one; the first step mentioned in Matthew 18:15), He says, “Convict him of his sin privately, with just the two of you present.” There is an obvious concern for confidentiality. At each stage thereafter, that concern seems equally important as other persons are brought in only when the offender refuses to listen.1

What then does one say when asked to keep a matter in confidence? We ought to say, “I am glad to keep confidence in the way that the Bible instructs me. That means, of course, I shall never involve others unless God requires me to do so.” In other words, we must not promise absolute confidentiality, but rather, confidentiality that is consistent with biblical requirements. No Christian can rightly ask another for more than that. However, because of the widespread ignorance of church discipline and of the biblical position on confidentiality, it is often necessary to explain what you mean by biblical requirements in the matter and sometimes even to go into detail as I have in the preceding paragraphs.

The matter of confidentiality has arisen as an issue in some pro-life centers tor unwed mothers. Certain centers have opted tor giving prospective mothers assurance of absolute confidentiality. But this means that when a Christian girl plans to have an abortion in spite of their counsel to the contrary, the center pledges not to tell her parents or her church. That leads not only to making an unacceptable vow, but possibly also to having complicity in the death of the child.

Obviously, there are situations in which a matter does not originate between two persons and, therefore, does not require the use of all the steps of discipline. For instance, in 1 Corinthians 5 we read about a man who was having sexual relations with his father’s wife (that is, his stepmother). It was a matter of notoriety since they were living together; it was not a matter between two individuals, but a matter between the man and the church. Paul begins discipline at stage five, telling the church to “put him out of the midst.” He does not go through the previous steps of discipline at all.

Was Paul exercising some special, apostolic prerogative? Absolutely not. As a matter of fact, he calls the church “arrogant” (v. 2) for not removing him on their own without his prompting.

Suppose there is a Christian woman who becomes pregnant. She is repentant. She has asked God’s forgiveness. What should she do now? In a few months it will be apparent that she is an unwed mother; the matter will then be public. You should advise her to come before the elders of the church to explain her position. When the elders have ascertained that she is in fact repentant, they should forgive her in the name of Christ and His church and announce to the congregation the fact that “so-and-so has become pregnant out of wedlock, has sought and received forgiveness in repentance before God and the elders, and is to be forgiven and received by all in love.”2 Warning should be given against any gossip or other wrong attitudes, and exhortations to assist and affirm love toward her should be made. This means that you have begun and ended discipline at step 4.3

The case in the preceding paragraphs raises another important point. Since the matter was initiated and resolved at stage four, before the church, it is not a matter for the world. This means that any announcement of the sin and repentance should be limited to the church alone. Guests and visitors might be dismissed before making the announcement at a church service or, possibly, a letter might be sent to the congregation (including a warning that no one but the membership is entitled to the information in it). But whatever way it is done, the matter should be kept at stage four; the world has no part in it.

Let’s take up another issue. Some think that if one Christian differs with the writings or public statements of another Christian on a point of doctrine, without rancor or any problem between them as persons, he is wrong for stating the differences publicly before going privately to the brother with whom he disagrees. That is a misconception. First of all, there is no unreconciled condition between them; they simply differ. Secondly, therefore, there is no matter of church discipline involved. Thirdly, even if this were a matter of discipline, the first party spoke or wrote publicly—he put it before the church or the world; he did not speak privately. For that reason it is appropriate for the second brother to write or speak as publicly as the first did in refuting what he thinks is a wrong interpretation of the Scriptures and which, therefore, he believes may hurt the church if he doesn’t. There may, of course, be doctrines so seriously wrong that he would have to prefer charges against him before whatever authorities of the church may be available for such purposes, and a disciplinary process may be set in motion at the fourth stage.4 But not all differences of belief or interpretation call for disciplinary action.

There are times, naturally, when a Priscilla and an Aquila will find it appropriate to “take aside” a modern-day Apollos and “explain God’s way to him more accurately” (Acts 18:26b), but not every situation either allows for this or demands it.

Consider another scenario in which the regular process of church discipline begins, not with step 1 or 2 but with step 3. Two Christians have a dispute that has led to bad feelings between them that do not disappear. Yet neither of them has asked for the help of one or two others. A third Christian becomes aware of the problem and of the rift between the parties; he sees them “caught” in some sin from which they are not extricating themselves. So, in obedience to Galatians 6:1-2 he moves in to help “restore” them to a place of usefulness in Christ’s church. Out of loving concern he temporarily bears their burdens in this altercation so that, being restored to their places in the church, they will soon be able to carry their own share of the load once again (v. 5).5 In this case, informal discipline is instituted at its last stage. If the third party is able to help the two persons6 to become reconciled, then the matter ceases at that point and need never take on formal dimensions.

Change the scenario just a bit. This time there is one Christian caught in sin. Another, in obedience to Galatians 6, goes to help him. Help is rejected. The second Christian continues to offer help in spite of the refusal, as indeed he should; he is rejected again, and perhaps again and again. He continues to offer help since the problem has not been solved and, as a matter of fact, has grown more serious. Finally, the one caught in sin becomes angered at the other for his persistence and no longer will talk with him about the matter. What must happen then? Clearly, a Matthew 18:15 situation has arisen out of the friendly offers of help: the two are now unreconciled. So the would-be helper approaches him once more to talk about that problem to bring about reconciliation between them. Refusal will lead to advancing the matter as tar along the discipline continuum as necessary.

So, there are any number of angles; discipline may begin at any stage in the process. Basically, the rule of thumb by which to determine where the matter should be handled is this: deal with the problem on the level at which it presents itself, making every effort to involve no one other than those already involved.

We shall have occasion to deal with some of these problems as we work our way through the five steps in the next five chapters.

1 At each point, a refusal of one or the other parties to “listen” is the operative factor that moves the course of discipline along to the next stage. The matter, therefore, is not arbitrary, but it does require a judgment call as to when such a stage has been reached. Refusal to listen would involve an unwillingness on the part of one or both parties to continue to speak and act in ways that are calculated to bring about reconciliation. Adequate time must be given, and a sufficient number of attempts at reconciliation should be made to be certain that it is impossible to get anywhere without advancing to the next step. Except in cases of divisiveness (to be discussed infra), it is always wise to err, it need be, on the side of caution, giving the benefit of the doubt in love (cf. 1 Corinthians 13:7, believing and hoping the best of all involved).

2 AIthough I shall have more to say about it in a future chapter, here I should at least mention the tact that a record of her repentance and the tact that the church considers the matter closed should be made in the elders' minutes to guard the future welfare of the repentant party.

3 Of course, she may need help in matters leading to self-discipline, so that counseling also may be indicated.

4 The process of discipline for doctrinal error is not substantially different from the discipline that Jesus discusses in Matthew 18. Again, apart from apostasy (rejecting the gospel; Hebrews 6:1 -6), no one is removed from the church for other errors who willingly receives instruction, but only those who refuse it (though elders and deacons, of whom greater doctrinal precision must be expected, may be deposed from office).

5 I have written extensively on Galatians 6:1-2 in a book entitled Ready to Restore, which see for details about how to do this.

6 Strangely, some never think of using church discipline, even informal discipline, when the two parties are husband and wife. Why not? A Christian husband and wife are not merely married persons, they are also brother and sister in Christ’s church. Most marital problems could be resolved early by active, informal disciplinary action.