The transmission of Buddhism to America is an epoch-making undertaking. For 2,500 years, Buddhism has played a central role in the religious life of Asia. Its philosophical schools, institutions, rituals, and art have informed the lives of countless people from the Iranian plateau to Japan and from Tibet to Indonesia. Throughout many centuries, it has taken on fascinatingly different shapes as it has adapted to many different cultures and regions, a process that is repeating itself as Buddhism moves west and into the United States. Essential in understanding this process is a grasp of the most elementary teachings of the Buddha and some of the vocabulary used within American Buddhist communities.

Teachings of the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha, was born in the sixth century B.C.E. in what is today Nepal. According to tradition, he was heir to his father’s throne as head of the Shakya clan, but instead chose at the age of twenty-nine to depart from the comfortable life of the palace, renounce his inheritance, leave his family, and retire to the wilderness in search of a way to end human suffering. Siddhartha set out on his quest at a time of great spiritual ferment in India, when ascetic philosophers and wandering sages were debating fundamental questions that remained central to the Indian religious traditions through subsequent centuries. What is the nature of human action, or karma? What role does karma play in shaping one’s life and fate? Is there rebirth after death? Assuming there is rebirth, is it possible to escape samsara, the endless wandering through round after round of death and rebirth? Siddhartha’s answers to these questions informed the development of Buddhism throughout Asia and continue to do so in the United States today.

For six years after leaving home, Siddhartha studied and practiced harsh ascetic disciplines taught to him by teachers he encountered on his journey. But at the age of about thirty-five, he discovered his own path during a long night of meditation sitting under a pipal tree. According to tradition, he entered a state of deep mental absorption, or dhyana, during which he observed the unfolding of his own many past lives, thus answering questions about death and rebirth. He also saw how karma influenced the shaping of events both in the present moment and in the future, not only in this life but in many lives to come. Most important, Siddhartha analyzed how karma worked to trap human beings in samsara, and he discovered a path or method to follow to gain liberation, an experience generally referred to as nirvana.

The term nirvana was originally borrowed from the physics of ancient India and meant the extinguishing of a fire. It literally means “unbinding,” reflecting the idea that fire was thought to be trapped in its fuel while burning but freed or unbound when it went out. The freedom and coolness connoted by the term reflect Siddhartha’s understanding that the path of liberation entails quenching passionate attachments to illusions that keep human beings trapped in suffering. He saw his path as “the middle way,” a point of balance between the sensual indulgence he engaged in as a youth in his father’s home and his teachers’ severe austerities.

As a result of his discoveries, Siddhartha became known as the Buddha, “the awakened one” or “enlightened one.” Many who subsequently followed his path also became awakened and, according to some traditions of Buddhism, there have been many buddhas. He is also called Shakyamuni, or sage of the Shakya clan, and Tathagatha, which means “thus come” or “thus gone” and signifies that the man who was Gautama achieved total liberation. Shortly after his awakening, he began to teach what he called the dharma, which means “doctrine” or “natural law.” He also formulated a discipline, or vinaya, for his most devoted followers.

The Buddha was not a Buddhist. That term came into usage only many centuries later when western observers used it to refer to the many traditions that had grown out of his teachings. The Buddha called his path the dharma-vinaya, the doctrine and discipline, and he taught it to numerous disciples over the course of the next forty-five years.

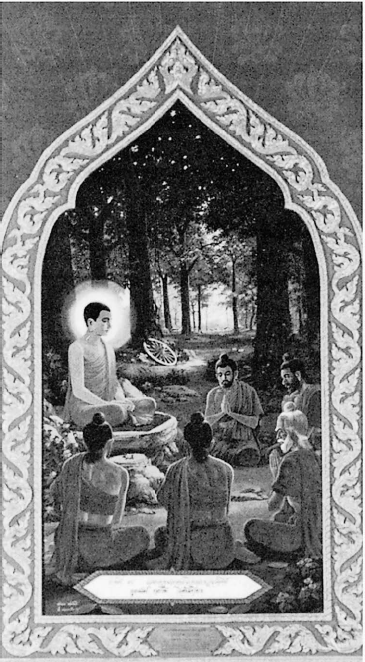

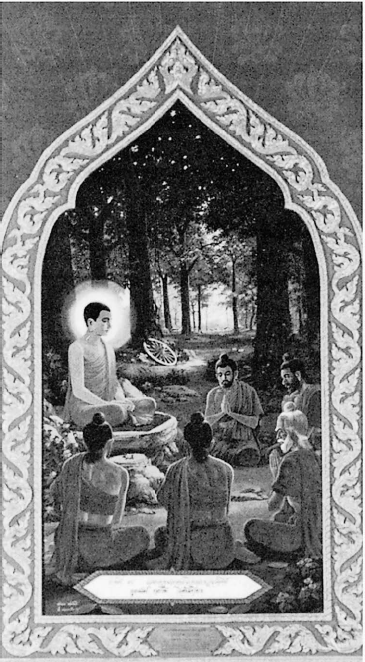

A great many scriptures or sutras are thought to contain the Buddha’s manifold teachings. Many were written by later Buddhists who, having attained awakening, claimed to speak with the Buddha’s authority. The dharma, after all, was not the Buddha’s personal property but was open to all who practiced the middle way and were awakened through it. According to tradition, however, Shakyamuni Buddha first delivered the essence of his teachings in the form of a sermon in Deer Park at Sarnath, several miles outside the city of Varanasi. The most fundamental of these teachings is known as the Four Noble Truths, which he offered to his listeners both as a diagnosis of the human condition and as a form of medicine or cure. Like Jesus’ teaching in the Sermon on the Mount in the Christian tradition, the Four Noble Truths have been the subject of a great deal of subsequent commentary in Asian Buddhism and remain a touchstone for most practitioners in the American Buddhist community.

According to tradition, the Buddha first began his work as a teacher at Sarnath in India, where he presented the essence of his awakening in the form of the Four Noble Truths. This image is from a sequence of paintings devoted to major events in the life of the Buddha at Wat Dhammaram, one of the major Thai temples in Chicago, Illinois.

FROM THE LIFE OF THE BUDDHA ACCORDING TO THE WALL PAINTINGS AT WAT DHAMMARAM, (C) 1997, WAT DHAMMARAM, THE THAI BUDDHIST TEMPLE OF CHICAGO

1. The First Noble Truth is that life is characterized by dukkha, a term translated as suffering, unsatisfactoriness, stress, or more colloquially, “being out of joint.” Dukkha conveys the essential quality of life in samsara. It means personal physical and mental pain; grief, despair, and distress; the anguish of loss and separation; and the frustration associated with thwarted desires. At its most subtle level, dukkha denotes the suffering people endure in clinging to things that are subject to disease, old age, and death, or to change and flux in general. Even one’s self, the most enduring thing one knows in life, has no fixed quality but is subject to dukkha. Buddhists consider this focus on suffering to be neither tragic nor pessimistic but a realistic and correct diagnosis of the central problem in human life.

2. The Second Noble Truth is that craving, or tanha, is the cause of dukkha. The Buddha pointed out that, at the most basic level, people always want what they do not have and cling to what they have in fear of losing it. This is a fundamental cause of suffering. On a more complex level, he taught that craving is rooted in ignorance, a misunderstanding of the transient nature of reality that leads people to seek lasting happiness in things that are subject to change.

3. The Third Noble Truth is that the cessation of dukkha comes when craving is abandoned. For many decades, western commentators emphasized the first two Noble Truths and saw the Buddha’s teachings as negative and contrary to the western humanistic spirit. Buddhists, however, place the emphasis on the truth that suffering can cease and that quietude, equanimity, joy, and even liberation from the wheel of samsara can actually be achieved.

4. The Fourth Noble Truth is the Eightfold Path, a prescription for how to engage in action or karma that will lead beyond samsara to nirvana, beyond suffering to liberation. Stated succinctly, it sounds much like a laundry list of good behaviors. But it contains the essence of the Buddha’s middle way and forms the foundation for Buddhist wisdom traditions, ethical teachings, and meditative disciplines.

The first two steps on the Eightfold Path—right view and right resolve—are forms of wisdom. Right view begins with the conviction that good and bad, healthy and unhealthy actions have real consequences. People shape their own destiny because they choose to act in ways that create good and bad karma. More specifically, right view means seeing life in terms of the Four Noble Truths. Right resolve builds on this understanding with the decision to abandon mental attitudes, such as ill will, harmfulness, and sensual desire, that stand in the way of liberation.

The next three steps—right speech, right action, and right livelihood—bear on ethics. Right speech is the recognition of the power of language to harm both oneself and other beings. Divisive and harsh speech, idle chatter, and untruthfulness are destructive, create bad karma, and thus should be avoided. Right action entails avoiding behaviors such as killing, stealing, and profligate or harmful sexual activity. Right livelihood requires that a Buddhist earn a living in a way that is honest, nonexploitative, and fair.

The last three steps—right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration—are more directly related to meditative practices. Right effort is the patient, persevering cultivation of good mental states. Right mindfulness requires attention to body, feelings, mind, and mental states in the course of meditation and maintaining presence of mind in daily living. Right concentration means the inward focusing of the mind and heart in states of mental absorption that lead to the kind of liberating insight the Buddha experienced in his own meditation.

In contemporary America, the Four Noble Truths are frequently interpreted in a modern, humanistic, and often secular spirit. But throughout Asian history, they have operated within a complex worldview that, for lack of better terms, might be called traditional or prescientific. The Buddha himself, and certainly later Buddhists, understood these and other teachings as operating on both personal and cosmological levels. Samsara is seen as a personal fact of existence and a cosmic process. Karma is not simply a part of human psychology but a force operating in the natural world. Rebirth is thought to take place among all forms of sentient life, and the worlds into which beings can be reborn include a range of heavens and hells. Impermanence is not simply a truth that has a bearing on ideas of selfhood and personal fulfillment but is a fundamental characteristic of the natural order of the universe.

As a result, Buddhism in Asia developed an immensely rich philosophical, cosmological, and mythological tradition that flourished up to and into the modern period. Just as many modern Christians have little trouble balancing faith in God, the divinity of Jesus, and belief in miracles and angels with a secular or scientific point of view, so too many modern Buddhists maintain strong convictions rooted in a traditional religious worldview. Some modern Buddhists understand the inhabitants of heavens and hells in metaphorical terms, but for others they are actual beings. Ideas such as samsara, karma, and rebirth may or may not continue to play an important role in their religious imagination. The Four Noble Truths and other basic Buddhist teachings may be fused with a secular and humanist outlook, but they may also be considered as directly related to a more traditional cosmology and worldview.

All this is to say that the introduction of Buddhism to America and the West entails more than importing a neat set of religious propositions or an ethical system. There are a wide range of spiritual, cosmological, and mythological dimensions that are often assumed to be a part of the Buddhist worldview. Some of the debate over what American Buddhism should be is rooted in questions about if, how, and to what degree traditional ideas and convictions should be reshaped to suit the very different ethos of contemporary America.

The Formation of the Sangha or Community

Shortly after the Buddha preached at Sarnath, his followers began to form the first Buddhist community or sangha. From the outset, many of his disciples sought to follow his example by leaving their settled lives behind, taking up the dharma and vinaya, living as mendicants, and practicing meditation. These monks (bhikkhus) and nuns (bhikkhunis) formed the basis of what would later become the Buddhist monastic community. The importance of Buddha’s example as teacher was perpetuated in the monastic tradition, where the relationship between teacher and student became institutionalized in lineages. These lineages played an important role in the transmission of the dharma throughout Asia in subsequent centuries and continue to be important today in many communities in the United States.

At about the same time, roles began to develop for the laity. Some people who held the Buddha and his dedicated followers in highest regard had no expectation of imitating their extraordinary undertaking. These men (upasakas) and women (upasikas) contributed money and goods for the support of monks and nuns, becoming a model for later Buddhist laity. The complementary roles played by monastics and laypeople became a pattern that was repeated as Buddhism later spread throughout Asia. Bhikkhus and bhikkhunis pursued the extraordinary religious goal of attaining liberation, while upasakas and upasikas provided them with support and sustenance, an act that was considered to be meritorious. Such merit-making was understood as a way to earn good karma for oneself or a loved one and was itself seen as an important religious practice.

Within the first century after the death of Shakyamuni, patterns of Buddhist practice began to emerge for both monastics and laity. The first Buddhist ritual was taking refuge, an act still repeated in ordination ceremonies, daily meditation sessions, and as a before-meal prayer in Buddhist communities throughout Asia and the United States. It consists of the simple formula “I take refuge in the Buddha. I take refuge in the dharma. I take refuge in the sangha.” The simplicity of what Buddhists call the triratana, the Triple Jewel or Gem, however, can be misleading. Over the centuries, Buddha, dharma, and sangha have taken on a wide range of different meanings. Buddha might refer to Shakyamuni or to another enlightened being. The dharma has been subjected to a great deal of philosophical and sectarian interpretation over the centuries. In some forms of Buddhism, sangha refers specifically to the monastic community. In others, it refers to a Buddhist priesthood. In still others it is taken to be a broadly inclusive term that refers to all Buddhists. In the United States, sangha may mean an informal group meditating together, a particular community who share the same tradition or teacher, or the entire American Buddhist community. The cyber-sangha, the sum of all those Buddhists who are part of the virtual community sustained by websites, Buddhist list servers, and dharma chat groups, has become a significant element in American Buddhism.

From early on, all Buddhists were expected to follow the five basic precepts, the panca sila—to refrain from killing, stealing, engaging in sexual misconduct, lying, and taking intoxicants. Monks and nuns, however, soon developed a far more rigorous and extensive code, found in the canonical Buddhist texts, that forms the heart of the monastic vinaya. The vinaya contains a wide range of rules concerning the food, dress, and dwellings appropriate to monks and nuns, their personal comportment, and ways to ensure the peaceful running of the community. Until the modern period, Buddhist monastics were routinely expected to practice celibacy, an area of discipline that has been loosened in some communities but rigorously adhered to in others. There are more than two hundred rules that govern traditional monastics, all of which are considered to be natural extensions of the Buddha’s original teachings.

Devotional forms of Buddhism soon emerged that were used by both monks and laity. Buddhists gathered together under pipal trees to recall the night of the Buddha’s enlightenment. These trees became known as bodhi trees, trees of awakening, and continue to be a major element in Buddhist iconography. Stupas, mounds containing relics of the Buddha, became major cult sites in Asian Buddhism. There are now many Buddhist stupas, perhaps as many as fifty of significant size, in the United States. The Buddha is also symbolized by an empty throne or footprints, images signifying that although the dharma remains on earth, Shakyamuni himself attained ultimate liberation. The lotus, a beautiful flower with roots planted firmly in mud, is a reminder that while nirvana is a transcendent goal, it is attained from within the realm of human suffering. By the first century B.C.E., the human image of the Buddha, which is found in virtually all forms of Buddhism today, came into widespread use. Standing, sitting, and reclining figures of Shakyamuni or another buddha are often complex symbols in which colors, hand gestures, and adornments all have esoteric meanings.

The general pattern for monastics and laypeople that emerged in Buddhism was not unlike that in the West during the Middle Ages. Monks and nuns formed a religious elite. They were the intellectuals, philosophers, teachers, poets, and religious practitioners at the formal core of the community, performing their roles sometimes brilliantly and at other times carelessly. Some monastics took on secular roles as diplomats and advisers at court. The laity, whether humble rank-and-file or royal patrons, deferred to them, although relations between the two camps were often fraught with tension and complexity. In one major way, however, these relations differed from those in the West. Many Asian schools of Buddhism developed traditions of temporary ordination, in which laypeople can take on the monastic role for a time and then return to their former way of life, with an ease not found in most forms of monastic Christianity.

The use of the term ordination in reference to Buddhism is, moreover, a source of further confusion. In the West, the common understanding is that ordination occurs after the completion of an educational process and marks the formal entrance into a religious profession as a priest, monk, nun, rabbi, or minister. In the Buddhist context, however, ordination often denotes a formal entrance into a protracted period of study and practice, one that may or may not lead a practitioner to take a “higher ordination,” to become a “fully ordained” monk, nun, or other type of advanced practitioner. As the monastic tradition moves to the West, where most Buddhists remain laypeople, there is a great deal of variation and ambiguity in the use of this language.

Within four or five centuries of Shakyamuni’s death, a highly complex Buddhist tradition had taken shape in India. Both monastic institutions and lay Buddhism prospered. The oral tradition that had grown up around the teachings of the Buddha was transformed into a written canon and schools of Buddhist philosophy flourished. Ritual, iconography, and musical expressions of Buddhist piety became highly articulated. Most developments in Buddhist history can be traced in whole or in part back to origins on the Indian subcontinent, even though Buddhism largely vanished from India after the twelfth century C.E., in large part as a result of the Muslim invasions. For this reason, the teachings of the Buddha that are now being transplanted to the West have been reshaped by centuries of adaptation to other Asian cultures from Sri Lanka to Korea.