The foundations of American Buddhism rest on a variety of national, regional, and sectarian traditions of Asian Buddhism. There are a great many forms of Buddhism in Asia, but three broad traditions have structured Buddhist thought and practice for many centuries. A comparable development is found in the West, where the teachings of Jesus are generally seen as expressed in Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant traditions of Christianity. In order to understand American Buddhism, it is important to have a general grasp of the leading principles of these traditions and their general place in Asian history and geography.

These three traditions are often called yanas, or vehicles that convey people from samsara to nirvana. They are also likened to rafts that carry people from one shore of a river to the other, from suffering to liberation. In this sense, the three major yanas share a common purpose, but differ due to their historical evolution in different parts of Asia. All three traditions are currently flourishing in America, but communication among them is limited both by ethnic and sectarian differences inherited from Asia and by the gulf that tends to separate Buddhist converts and immigrants. Many American Buddhists hope and expect that the presence of these many different traditions in the United States will provide an opportunity for greater mutual understanding among all of them, and for the emergence of new forms of Buddhism suited to the needs of Americans and American society.

Theravada, the Way of the Elders

Theravada is the most traditional and orthodox of the three vehicles. Many centuries ago, Theravada, which means “the way of the elders,” was one among a number of early schools of Buddhism. In about the second century of the common era, these schools were collectively referred to by their detractors as Hinayana, or “little vehicle,” a pejorative term coined to contrast their traditionalism with the more expansive and innovative spirit of a second great tradition, Mahayana, which means “great vehicle.” All of the older Hinayana schools have long since died out, except for Theravada. While ancient tensions between Theravada and Mahayana have abated in recent centuries, the contrast between the two remains; it is an important way to highlight different religious emphases in the Buddhist tradition.

Theravada Buddhism is based on the canon of Buddhist scripture written down in Pali, an ancient Indian language, some two thousand years ago. Many scholars regard the Pali canon as the textual source closest to the teachings of Shakyamuni, although there are also very early texts in Sanskrit, another Indian language of great antiquity. In translation, references to Buddhist concepts are often made in either language, which are themselves related. For instance, dharma is expressed as dhamma in Pali, and nirvana as nibbana. For many centuries, Theravada monks and nuns have closely imitated the life of the historical Buddha and have attempted to maintain his dharma and vinaya as preserved in the Pali canon. They consider the Eightfold Path and the monastic codes as strictly authoritative. Deviations were and are considered delusory and hindrances on the path to liberation.

Theravada scripture contains a great deal of sophisticated reflection on the dharma, vinaya, cosmology, and human psychology, but the monastic path that took shape in the tradition many centuries ago was relatively direct and simple. Family life, sensuality, and worldly attachments were seen as obstacles to liberation. In time, a succession of stages to enlightenment were recognized within the monastic community. There were “stream-winners” who had gained the path and “once-returners” whose level of attainment assured them not more than one rebirth. The central and most venerable figure in the tradition, however, was the arhat, or “worthy one,” who possessed the certainty that delusory and egotistic grasping had been extinguished. Arhats suffered no attachments in this life and expected no rebirth. Monastic Theravada Buddhism remains more or less oriented to these same ideas today.

In Theravada Buddhism, the monastic community is identified with the sangha while laity play a complementary, if somewhat secondary, role. Lay Buddhism is largely devoted to ritual practices, devotional expressions, and temporary ordinations that often serve as rites of passage, all of which are understood to be occasions for merit-making. The idea behind the relationship between monastics and laypeople has its own compelling logic. If one is moved to become a monk or nun and pursue liberation, this is caused by good karma in past lives. If one pursues the more ordinary goals of household and family, this too is a result of karma. Gaining merit is an important religious activity because it is thought to secure a better rebirth in which the exalted goal of nirvana might be pursued. In one sense, the Theravada tradition is marked by clerical elitism, but in another, lay Theravada Buddhists are comparable to churchgoing Christians who may be deeply pious and highly spiritual but are quite willing to forego the obligations of the clerical life of nuns, priests, and ministers.

Elements derived from the old Hinayana schools are found throughout Asia, but the Theravada tradition is today the dominant form of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, and most other countries in southeast Asia. They all share a strong family resemblance in their ritual life, aesthetics, and institutional arrangements. They vary because Theravada has absorbed regional animistic religious traditions that remain important in rural south and southeast Asian villages, and has been reshaped by regional politics and history. There has not been a women’s monastic order in the Theravada tradition since the tenth century C.E., when the bhikkhuni lineages were wiped out in the course of warfare, but more informally organized women pursue monastic practice in a number of countries. The questions of if and how these lineages are to be reestablished are a major source of controversy in the Theravada world today.

Theravada Buddhism seems to have a very bright future in the United States. It is one of the major forms of Buddhism in the Asian American immigrant communities, and the meditation techniques of the Theravada traditions are among the most popular forms of lay practice in the convert community.

Mahayana, or the Great Vehicle

Mahayana Buddhism began to emerge around 100 C.E. as a set of distinct emphases in the interpretation of the Buddha’s teachings. For centuries, older and more traditional Buddhists and Mahayanists studied and practiced together in monasteries on the Indian subcontinent. The gulf that eventually opened up between them is largely a product of geography, because the innovations central to Mahayana later became dominant in China, Vietnam, Japan, and Korea. The tradition took the name Great Vehicle because its proponents saw the orthodoxy of the way of the elders as too narrow. Its development into a distinct tradition also gained momentum as Indian Mahayana Buddhists incorporated philosophies and devotional practices they borrowed from Hinduism, which remained the dominant tradition of India, into the dharma. As Mahayana spread outside the Indian subcontinent, it further incorporated elements drawn from Taoism, Confucianism, Shintoism, and other indigenous traditions found in the civilizations of northern and eastern Asia. Many American Buddhists, whether converts, immigrants, or old-line ethnics, are part of the Mahayana tradition.

The contrast between the arhat and the bodhisattva is one of the chief ways of differentiating between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. In the early centuries of the common era, some Buddhists in India began to develop a critique of the arhat as the ideal practitioner of the dharma and vinaya. They viewed the pursuit of personal liberation by individual monks and nuns as fundamentally selfish. Mahayana philosophers began to give prominence to a different ideal, the bodhisattva who aspired to Buddhahood—the attainment of wisdom or supreme enlightenment infused with a compassionate concern for all beings. On the level of practice, this emphasis gave rise to the bodhisattva vow, a pledge that a person on the path, whether monastic or lay, would forego ultimate liberation until such time as all people became free of suffering. On a more exalted level, this fostered the emergence of cosmic bodhisattvas, great mythological figures such as Manjusri, Avalokiteshvara, and Kuan Yin, who were thought to reincarnate through numerous lifetimes, always foregoing nirvana in order to teach wisdom, compassion, and the liberation of all sentient beings. The ideal of the bodhisattva is central to Mahayana thought and practice and plays an important role in its iconography and art.

This shift in understanding the dharma was also expressed in new schools of philosophy whose consequences were far-reaching. Mahayana Buddhists rejected the contrast between samsara and nirvana, seeing the two as interpenetrating rather than as distinct modes of being. They expressed this unified view of reality in terms of nonduality. There was neither nirvana nor samsara, this world or another; all such distinctions rested on concepts, ideas, and discriminations considered illusory. Philosophers expressed this nondualism in terms of shunyata or emptiness, the idea that everything in the universe is devoid of fixity and permanence. But emptiness also conveys the idea that beyond illusory distinctions is the blissful clarity of universal wisdom and compassion. Mahayana Buddhism is universalistic in the largest sense of the term. In some schools of philosophy, all sentient beings are thought to have the potential to realize awakened Buddha mind. Everything is ultimately thought to partake of Buddha nature. In analogous Christian terms, it is as if Mahayana philosophers argued in highly refined dialectics that heaven is earth, that eternity and the present are the same, and that the beatific vision of God is seen in all of creation. As a result of these shifts in interpretation, Mahayana Buddhists tend to speak of realizing Buddha mind or Buddha nature rather than attaining total liberation.

The Mahayana worldview was articulated in new scriptures such as the Diamond, Heart, Avatamsaka, and Pure Land sutras. Given Mahayana views about the universality of Buddha nature, the teachings in some of these, such as the Lotus Sutra, were readily attributed to Shakyamuni Buddha. But there are in Mahayana literature many buddhas and bodhisattvas. Some, such as Amida and Maitreya, are seen as saviors and play important roles in devotional Buddhism. Others are wise and compassionate teachers and brilliant preachers. Mahayana sutras also delight in depicting a universe vast in both time and space, infused by the energy of cosmic buddhas and bodhisattvas and sectored into many buddha lands and buddha fields.

Within this expanded cosmic view, Mahayana gave prominence to ideas inherited from earlier Buddhism about the interdependence of all beings, but with a new twist. For older schools of Buddhism, the interdependent nature of samsara was inescapably tied to impermanence, clinging, and suffering. In light of Mahayana nondualism, however, interdependence was more positively interpreted as interconnectedness or interrelatedness and, as such, something to be celebrated. With no interest in speculative questions about who or what created the universe, Mahayana Buddhists developed a vision of it as an endless cascade of causes and effects, driven throughout by moral purpose. Mahayana Buddhists often describe the interdependence of all beings as Indra’s net. Indra was an ancient god of India, and his net became a metaphor for the interconnected universe in which each point of life was a jewel of Buddha nature, a node of potential enlightenment, sensitive to any movement toward enlightenment that occurred at any time and in any sector of the universe. The point of Buddhist practice was to realize this. Many American Buddhists are now applying Mahayana ideas about the interdependence of all beings to environmental and social concerns and see in these beliefs a spiritual complement to modern scientific theories about ecology and astrophysics.

Mahayana is a major influence in the United States, but within the tradition there are many distinct lineages, sects, and movements, a few of which are playing particularly important roles in the creation of indigenous forms of American Buddhism. In Chinese Mahayana Buddhism, there are many philosophical systems and regional traditions. But both monastic and lay Buddhism tends to be eclectic in approach to practice and philosophy, drawing together elements that in Japan and Korea later took shape as sectarian movements. As a consequence, Chinese Buddhism in this country, which flourishes primarily in Chinese immigrant and ethnic communities, is known for its diversity and complexity of expression. Chinese influence is also strong in the Vietnamese American Buddhist community.

Korean and Japanese Buddhism were originally imported from China. Over the course of centuries, however, they absorbed many elements of the indigenous traditions of their two countries and tended to reshape elements of Chinese Buddhism into particular sects and movements. Lay Korean Buddhism is practiced primarily in Korean American immigrant Buddhist temples, while the monastic tradition has been established in America in several thriving centers in the convert community.

Three Mahayana traditions of Japan are of particular importance in the United States; their distinctiveness is such that each requires a brief description here that will be further developed in later chapters. To a large degree, all three emerged as separate forms of Japanese Buddhism around the thirteenth century, and as protests against corruption in the monastic sangha. The founders of two of them, Shinran and Nichiren, emphasized devotional elements of Buddhist practice to suit lay practitioners in an age they saw as marked by the degeneration of the dharma. The third, Dogen, was more concerned with revitalizing the meditative disciplines practiced within the monastic community.

Shin Buddhism

Shin Buddhism is in the Pure Land tradition, a broad current in east Asian Buddhism that centers on the Amida Buddha and his paradise or Pure Land. Shinran, a monk in the powerful monastic establishment of Japan, was among the most influential founders of Shin Buddhism. Convinced that common people could not attain liberation in a degenerate age, he abandoned his monastic vows, married, and established himself as a married Buddhist cleric, a move that at the time was considered revolutionary. The doctrine he promulgated gave a unique emphasis to an ancient tradition of Pure Land Buddhism. In a way quite consistent with Mahayana doctrines about universal Buddha nature, he taught that all people were guaranteed access to the Pure Land through the grace and mercy of Amida. The practice he taught was chanting the name of Amida out of a sense of respect, reverence, and gratitude. Shin Buddhism, which eventually split into a number of sects, became a highly popular and influential form of Buddhism in Japan. In the nineteenth century, one branch, the Jodo Shin-shu sect, was brought by Japanese immigrants to the United States, where it is today the oldest institutionalized form of American Buddhism.

Nichiren Buddhism

Like Shinran, Nichiren left the monastic establishment to become a religious reformer. His passionate conviction that the dharma was degenerate in Japan and the political importance he saw in this development have led many commentators to liken him to Martin Luther. Unlike Shinran, who tended to see other forms of Buddhism as partial and incomplete, Nichiren saw them as false and deluded. Like Shinran, Nichiren promulgated chanting as the most efficacious form of practice, but he focused his devotion on the Lotus Sutra, which many consider the most important text in Mahayana Buddhism, rather than on Amida Buddha and the Pure Land. Nichiren was a zealous missionary who envisioned Japan as the center from which his doctrine would spread throughout the world. Although he died in obscurity, his movement flourished, eventually developing a variety of sectarian traditions. There are a number of schools of Nichiren Buddhism in the United States, but the most prominent are Nichiren Shoshu Temple and Soka Gakkai International, both of which trace their American roots to the mid-twentieth century. They have the distinction of being the major form of lay devotional Buddhism with a substantial following in the American convert community.

Soto and Rinzai Zen

Zen Buddhism is a Japanese form of what in China was the Ch’an lineage of Mahayana Buddhism. Dogen was among Japan’s most important Zen teachers. He traveled to China in about 1220 C.E. and returned to renew Zen in Japan; he is remembered as the founder of the Zen Soto school. The words Ch’an (Chinese) and Zen (Japanese) are related to the term dhyana, which in India meant “mental absorption.” This origin points to the emphasis this tradition places on meditation, whose chief form in Japan is called zazen, or “sitting in absorption.” Soto Buddhists emphasize shikantaza, “just sitting,” a method of meditation in which the mind rests in a state of brightly alert attention, free of all thoughts and directed to no particular object of contemplation. But the Soto school became very popular in Japan because its monks also performed rituals for the laity, creating a relationship between monks and laypeople not unlike that in Theravada Buddhism.

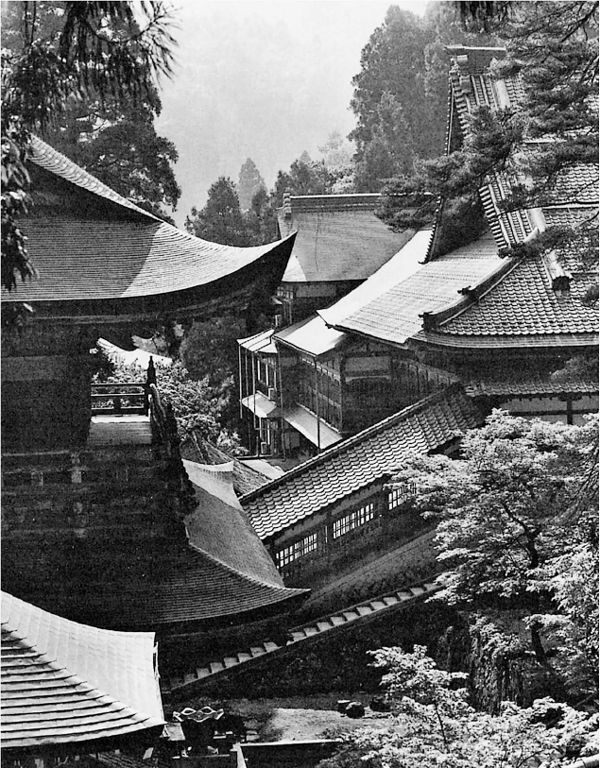

In all three vehicles or traditions, monastic institutions have played a critical role in the transmission of the dharma and in the creation of Buddhist philosophy, literature, architecture, and art. Eiheji, shown here, is the head monastery of the Soto school of Zen in Japan, one of the most prominent forms of Buddhism to have taken root in the United States.

DON FARBER

Another school of Zen, Rinzai, also took on a distinct shape in Japan at about this time. Rinzai is often characterized as less formal and ritualistic than Soto Zen. This school also emphasized the systematic study and contemplation of koans—brief stories or fables whose enigmatic quality is meant to drive the mind toward enlightenment. Rinzai Zen has been important in American Buddhism since the early twentieth century, but the Soto school began to move into prominence in the 1960s. Many American Zen practitioners currently use elements drawn from both the Soto and Rinzai schools.

Vajrayana, the Diamond Vehicle

Some see Vajrayana as an extension of Mahayana, but others see it as a distinct Buddhist vehicle. It derives its inspiration from texts called tantras; thus it is also called Tantric Buddhism. Vajrayana arose in northern India and became important in the eclectic Buddhist mix in China and in Japanese Buddhist history. But Vajrayana became most thoroughly developed in Tibet and the surrounding regions of central Asia, where it fused centuries ago with indigenous shamanic religions. Vajrayana Buddhism was long dismissed by scholars and other observers as a corruption of the dharma. But in the last few decades, it has come to be seen as a brilliant expression of the teachings of the Buddha that developed in a unique setting. Much of this change in evaluation can be traced to the work of scholars, both Tibetan and American, in the United States.

Vajrayana draws upon the teachings and meditation techniques of the older, Hinayana schools, Mahayana cosmology, and forms of ritual practice adapted from Hinduism. Vajra means “diamond” or “adamantine” and is meant to describe the clear and immutable experience of the luminous void that is thought to be the essence of the universe. But Vajrayana practitioners also understand it to be the most complete form of the dharma, which if practiced assiduously can lead to total liberation in a single lifetime. In the last three decades, the tradition has come to play an increasingly important role in the Buddhist community in the United States, where the terms Vajrayana, Tantra, and Tibetan Buddhism are often used synonymously.

Vajrayana consists in part of visualization methods used to infuse the body, speech, and mind of the practitioner with the body, speech, and mind of enlightened beings. Mudras are ritual gestures used to express the qualities of particular bodhisattvas and buddhas whom a practitioner is visualizing. Mantras, chanted syllables or phrases, are used to harness speech to the path of liberation. Mandalas, symbolic representations of the forces of the universe in the form of divine beings, are used as aids to visualization. In early Tantra, sexual practices also played a role in harnessing the body to spiritual transformation. In Tibetan Buddhism today, this kind of practice is primarily expressed in art and iconography. Male figures represent compassion, females wisdom. When joined together in sexual union or yab-yum, which literally means “father-mother,” they represent the unity of the two, which is understood to be the essence of the universe.

Mudras, mantras, and mandalas are used in the visualization methods of meditation in Tibetan, or Vajrayana, Buddhism. This sand mandala was constructed in the home of a television producer in Hollywood. Many in the entertainment community of the 1990s became outspoken supporters of the Tibetan struggle for religious and cultural independence.

DON FARBER

Tibetan Buddhist leaders are called lamas or teachers. Those who have completed a long course of study are often given the honorific title rinpoche, or “precious one.” Many of them are also considered tulkus, reincarnations of prominent and highly evolved lamas. Tibet’s major religious institutions are organized into four schools or orders, the Sakya, Gelugpa, Kagyu, and Nyingma. Within these schools are many lineages and sublineages, all of which have distinctive traditions and practices inspired by the examples of heroic founders and teachers. Each is associated with different buddhas, bodhisattvas, demon protectors, and guardian spirits. Tibetan Buddhists, however, also teach more austere meditative techniques that resemble Zen. One of these is Mahamudra, or “the great seal,” which is considered the highest form of practice among the Kagyus. A similar practice in the Nyingma tradition is called Dzogchen, “the great perfection,” which its practitioners consider the definitive, secret teaching of Shakyamuni Buddha. Formal monastic institutions play an important role in Tibetan Buddhism, but there is also a lively and influential tradition of married clergy. The power of these and other institutions in Tibet remained immense into the middle of the twentieth century.

All these traditions and institutions share strong resemblances that point to their origins in a shared national history. Tibetans also share a number of national figures, such as Gesar of Ling, a great warrior, king, and dharma hero celebrated in epic and song, and Padmasambhava, “the lotus-born,” who is credited with taming the demons of Tibet and bringing them into the service of Buddhism. Tibetans consider Padmasambhava a second Buddha. Since the seventeenth century, the Dalai Lama, who is the head of the Gelugpa school, has also been the Tibetan head of state. All these traditions have been placed in serious peril as a result of the Chinese invasion of Tibet in the 1950s, an event that helped precipitate the transmission of the dharma of Tibet to the West. The fact that Tibetans are a community in exile has given a distinct shape to the processes by which it is being adapted in the United States.

In the last century or two, the teachings of the Buddha as expressed in all three vehicles have been further transformed in response to developments from European imperialism to industrialization, urbanization, secularism, and World Wars I and II. These and other developments have shaped an Asian Buddhist landscape that varies from country to country and region to region. The overall impact of modernity on Asian Buddhism, however, resembles more familiar effects in the West. In general, the great monastic traditions that flourished in medieval Asia have declined in influence over the past several centuries. There has been a parallel trend toward laicization, encouraged by the emergence of Asian democracies. New religious movements have also flourished in many countries, most noticeably in Japan, all of which owe a great deal to the past but are distinctly modern in their tone and emphases. Despite all these changes, Buddhism’s basic vocabulary and many traditions remain inextricably rooted in history, as is the case in modern Judaism and Christianity. Despite the Anglicization of Buddhist philosophy and practice in the United States, this vocabulary remains essential to any discussion of the American Buddhist landscape today.