1///GEORGE WASHINGTON AND THE AMERICAN PATRIOTS AT YORKTOWN, 1781

The decision to establish Valley Forge as a permanent base for the revolutionary American army, two years after the outbreak of war, kept alive the spirit of resistance despite the British regular forces ranged against them. Moreover, it provided a depot where Patriots could train and learn the art of war. For months their experiment in creating a standing army seemed close to collapse, but, in the end, a new American army emerged that would march to victory at Yorktown.

In the winter of 1777, the American colonists who had taken on the might of the British empire were in trouble. With supplies dwindling to a critical level their commander, George Washington, pleaded with Congress to provide food, clothing and shoes for his fledgling army as a matter of urgency. He wrote: ‘unless some great and capital change suddenly takes place … this Army must inevitably … starve, dissolve or disperse, in order to obtain subsistence in the best manner they can’. Washington had taken his men into winter quarters so as to prevent the total collapse of his force. In previous winters, men had drifted away from their units in such numbers that it was almost impossible to maintain an army at all: this meant that they lacked cohesion when confronted by the British. Time and again they were driven from the field because they lacked the ability to function together effectively.

Washington’s choice of Valley Forge in Pennsylvania as the location to keep his army intact over the winter was based on sound strategy. Having fought the Battle of White Marsh in December 1777, Washington’s base protected the nearby farmlands of Pennsylvania from British raiding parties, but kept enough distance between him and the British army at Philadelphia to prevent a surprise attack. High ground, namely Mount Joy and Mount Misery, protected the site from the west, and the Schuylkill River provided both a defensive barrier to the north and a supply of fresh water. Hundreds of wooden huts had to be built to accommodate the 12,000 or so men at Valley Forge, while revetted earthworks strengthened the perimeter. The chief problem, though, was a lack of provisions. Food was scarce and, although fresh bread was sometimes available, soldiers were forced to depend on a mash of flour and water called ‘firecake’. Supply of animal fodder was also intermittent, and many of the cavalry mounts and draught horses died in the cold weather. Uniforms were not available, and some of the troops were dressed in rags. In damp, fetid huts, inadequately fed and without winter clothing to keep out the cold, many men were incapacitated by disease. Typhoid, dysentery and pneumonia killed perhaps as many as 2,000, with a further 4,000 reported as unfit for duty. Inevitably, under such circumstances, many men began to desert.

In December 1777, Johann De Kalb wrote: ‘Our men are infected with the Itch, a matter which attracts very little attention either in the hospitals or in the camp. I have seen poor fellows covered over and over with scab …. We … are already suffering from want of everything. The men have [had] neither meat nor bread for four days, and our horses are often left without any fodder.’ A surgeon of the camp listed the problems in his private journal: ‘Poor food – hard lodgings – cold weather – fatigue – nasty clothes – nasty cooking – smoked out of my sense – the devil’s in it – I can’t endure it – why are we sent here to starve and freeze? … here, all confusion – smoke and cold – hunger and filthiness …’ He noted with bitterness that ‘yesterday upwards of fifty officers resigned their commission’. The officers who left took their servants with them. Some commissary officers sold the camp’s flour to the citizens of Philadelphia – or perhaps to the British. Soldiers simply abandoned their posts and used guard duty as an opportunity to run away from military service. Drunkenness and insubordination were serious problems.

Camp indiscipline extended to bad hygiene and the mishandling of supplies. In the orders of 13 March 1778, there was a note that ‘the carcasses of dead horses are lying in and near the camp, and that the offals near many of the commissaries’ stalls still lie unburied, that much filth and nastiness is spread amongst the huts, which are, or soon will be reduced to a state of putrefaction’. Criticism began to extend to Washington himself. While some blamed Congress, others, like the veteran fighter Major General Charles Lee, felt Washington was ‘not fit to command a Sergeant’s Guard’. But quarrels between the leading officers were not uncommon and several duels took place that winter.

Nevertheless, Washington did manage to retain a sizable portion of his force and to improve it throughout the first six months of 1778, and it is this achievement that makes Valley Forge so significant. By doing so, Washington kept the flame of the Revolution alive. Indeed, his efforts made it possible to establish a more solid foundation for the American cause. Two elements in particular were crucial to his success: the involvement of patriotic citizens, especially the women; and the training programme implemented by Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben.

The camp followers of any eighteenth-century army were vitally important. In the absence of formal military services and logistics, women often acted as the victuallers, nurses, seamstresses and labourers of the force. These regimental camp followers were crucial to sustaining Washington’s army at Valley Forge, not only providing rations and carrying out necessary repairs, but also bolstering the faltering morale of the troops. Billeted with the men, this little army of women and children prevented wholesale desertion.

The greatest contribution to the development of the army came from Baron von Steuben, a former Prussian army officer who had served under Frederick the Great. Washington quickly appointed the volunteer von Steuben to the duties of Acting Inspector General. Although the baron spoke almost no English, he realized that each American unit was using its own variation in drill, musketry and manoeuvre. Soon after his arrival in February 1778, von Steuben drew up his own drill and training manual, cutting the corners of the formal and long-winded European methods so as to standardize all practices. His staff translated the manual from von Steuben’s French version and began to disseminate it. Von Steuben himself worked with individual units, often demonstrating drills and, through translators, taking time to explain the processes. The approach was considered revolutionary by some American officers, since soldiers had never been expected to understand drill and manoeuvre, only to obey. Though progressive, von Steuben was no saint: his poor command of English led to misunderstandings and frustrations, and he often exploded with rage. This so amused the troops that, in time, von Steuben learnt almost to caricature himself, using a mixture of threat and humour to win over the men.

The training was relentless. Parades started at six o’clock in the morning and continued for two hours. At nine, the parades began again for three hours. At noon, non-commissioned officers were trained, and instruction for the men ran all afternoon. Specialist tuition in tactics and leadership was given to the officers with a particular emphasis on their getting to know their men by name and character. There were lectures on camp hygiene, kitchen maintenance, changing bedding, washing. There were sessions set aside for the manufacture of weapons and gunpowder, for the repair of tools and arms, and for the construction of earthworks led by French engineers and Brigadier General Louis Duportail.

With sub-units mastering the discrete skills of marching in line and column, loading and firing and responding to commands, von Steuben turned to the movements and direction of larger formations. Companies, regiments and then brigades eventually learnt the business of battlefield drills. Von Steuben also recognized that the Patriots had hitherto feared the British bayonet charge, even when they occupied entrenched positions; he therefore introduced measures to build confidence and instil aggression into the American forces when making their own attacks with the bayonet. Von Steuben was thus responsible for the creation of a regular American army that could fight the British on their own terms and retain the field. Although the Patriots would continue to rely on irregular tactics and elements of guerrilla warfare, there was an understanding that victory could be achieved only by adopting the offensive and taking the fight to the British.

When France allied with the American revolutionaries in May 1778, this new regular force was augmented by European professionals both on land and at sea, greatly adding to their strength. The French alliance also had the effect of changing the British strategy completely: London could not afford to view the American colonies as the main theatre of operations when France posed a threat much closer to home. Moreover, Britain was more concerned with the protection of the West Indies and its colonial possessions in India from France, and so was forced to divert naval and land resources to these other regions.

The return of better weather and the emergence of a well-trained core at the new army at Valley Forge drew back men who had deserted over the winter. New volunteers also appeared, who were provided with fresh uniforms and integrated into the improved formations. A spirit and pride had evolved which could not easily be extinguished, and by the summer of 1778 the American army was able to take to the field with confidence.

In light of the French alliance the British, led by their recently commissioned commander Sir Henry Clinton, decided to quit Philadelphia and to fall back to New York. Unable to load his men aboard ships in the Delaware River because of a lack of transports, Clinton had to march the army overland. The column of troops and supply wagons extended over 12 miles (19 km), which made it vulnerable, and Washington felt the time had come to test his new Continental Army. In stifling heat, the Americans tried to concentrate their forces and catch Clinton at Monmouth County Courthouse in the village of Freehold, New Jersey. The two sides clashed on 28 June 1778, but owing to Lee’s hesitation the Americans were bundled back by British Grenadiers. Clinton and the British escaped intact, but the American army had been tempered in battle and it was only a matter of time before they made use of their training and experience to better effect.

In 1781, the British were still able to defeat the American forces sent against them. Quartermaster General Nathanael Greene (who had kept up a campaign of exhausting his British pursuers) was beaten at Guildford, Connecticut, on 15 March that year. But the tide was turning. Greene exemplified this transformation of the American resistance. In 1774 he had helped organize a local militia in Rhode Island, and used the opportunity to study military tactics at first hand. His natural talent for organizing was recognized by Washington, who had appointed him the commander of Boston in 1776, and Greene was also made responsible for constructing field fortifications at Long Island. He tried unsuccessfully to defend Fort Washington on the Hudson River, and took part in the battles of Trenton (New Jersey) and Germanstown (Pennsylvania) with varying success before becoming the Quartermaster General at Valley Forge. He continued his responsibilities for logistics and supply while commanding operations, but he resigned in protest at what he regarded as political interference in the supply of the army. However, the defeat of each of the armies in the south led to his urgent appointment as overall commander of the entire region from Delaware to Georgia, and Washington’s second in command. In the space of just six years, he had risen from the rank of private in the Militia to Major General in the Continental Army.

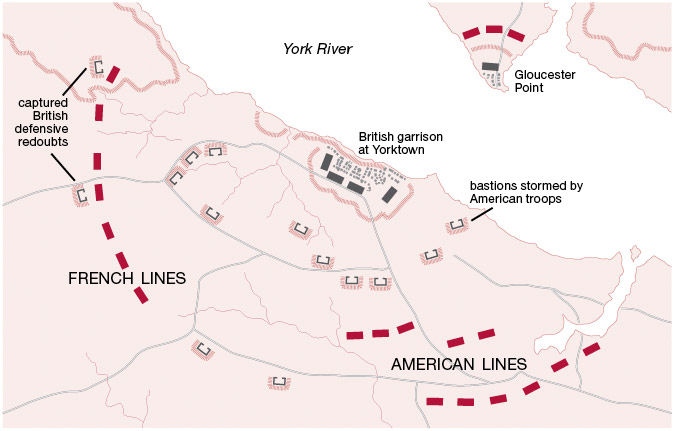

Having allied with the French and built up their forces over several campaigns, the American Continental Army was finally able to bring greater numbers against the British. The capture of the two bastions near the walls on the right flank at Yorktown made the defences there untenable.

When Greene took command of the south, his forces were in disarray. Dividing his troops to evade annihilation, he organized an escape march and managed to put his force across the Dan River out of reach of the British in February 1781. The following month, he tried to concentrate his various units again at Guildford Courthouse and, although driven from the field, inflicted such losses on the British that they were forced to fall back. He suffered further setbacks in battle, but nevertheless secured South Carolina. A self-trained soldier, Greene once remarked: ‘We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again.’

The British were not able to afford this steady stream of casualties, and the Americans were able to muster more men to sustain their resistance. Furthermore, with French assistance, they had superior supplies of arms and munitions. In the late summer of 1781, the British General Cornwallis found his army outnumbered by a Franco-American force at Yorktown, Virginia. The arrival of a French fleet, which bested a covering British flotilla, prevented the relief of Cornwallis’s garrison, and this encouraged the Americans to go on the offensive. Although Yorktown consisted of a series of entrenched bastions, connected with ramparts and ditches, the Americans enjoyed a superiority of firepower and on the first day alone, they fired 3,600 round shot into the defences. Cornwallis concluded that, with his ragged force ‘against so powerful an attack … [we could] not hope to make a very long resistance’. He had only 3,250 men fit for duty, and the rest of the garrison was forced to shelter below the sandy river cliffs to avoid destruction. The Continental Army daily inched its guns closer to the main defences, eventually reducing the range to 300 yards (275 m). No man could stand on the parapets without being shot down.

On 14 October, one French and one American battalion made a night attack on two vital bastions on the left of the British line. Night operations are complex and usually guarantee success only if the personnel are well trained. It is a testament to the progress made since Valley Forge that the Americans executed such a textbook attack so efficiently. One soldier recalled how he and his comrades had ‘arrived at the trenches a little before sunset’ and that before dark every man was ‘informed of the whole plan’. The first line consisted of sappers armed with axes, whose job was to cut through the abattis (a fortification made with sharpened wooden sticks); this cleared the way for the assault troops behind, led by officers with bayonets fixed to long staves. The soldier continued: ‘at dark the detachment … advanced beyond the trenches and lay down on the ground to await the signal for the attack, which was to be three shells from a certain battery … all three batteries in our line were silent, and we lay anxiously waiting for the signal.’

Their cool discipline was tested to the extreme when at last the signal guns opened fire, ‘three shells with their fiery trains mounting the air in quick succession – the word “up”, “up”, was then reiterated through the detachment. We moved towards the redoubt we were to attack with unloaded muskets.’ As the Americans and French dashed forward the British sentries made a vain attempt to stem the rush, but within moments the Americans were scrambling over the banks into the first bastion. The fight was quickly settled, and the two redoubts carried. Cornwallis wrote to Clinton that ‘our situation now becomes very critical; we dare not show a gun to their old batteries and I expect that their new ones will open tomorrow morning’. In fact, the British garrison was already down to the last of its meagre rations. The defences were strewn with the dismembered dead. Farriers made daily rounds to execute dying horses. Some soldiers deserted. Cornwallis made one last desperate attempt to save his small force. As 350 men made a heroic but hopeless sortie against the nearest batteries, the advanced party of the garrison slipped across the York River to Gloucester Point. As the second wave prepared themselves a storm blew up and scattered the small boats. With all hopes of escape lost, and with the Americans renewing their terrific cannonade against the crumbling earthen ramparts, Cornwallis sought to tender terms of surrender. The British troops, some weeping, others angrily casting down their arms, were nevertheless surprised to find themselves treated with ‘astonishing kindness’ by both American and French soldiers.

The British capitulation at Yorktown did not conclude the American Revolutionary War, but the event did mark the completion of a process of professionalization of the American army. It was also a clear victory for the Patriots after years of setbacks and defeats. At Valley Forge, the Revolution had seemed in danger of collapse, but the achievement of that encampment was to sustain and then develop a new army, whose success at Yorktown indicated that the Americans had gained the upper hand in the struggle. From this point onwards, backed by the French army and navy, the revolutionaries could withstand the British. Just two years later, in 1783, the war was concluded, and the Americans had realized their dream of independence. The transformation of the army at Valley Forge established an important symbolic principle during the Revolution – namely, that, despite the odds against them, American citizens had it within their power to determine the course of their own history. Valley Forge became more than a mere training depot: it was the springboard for a sense of national achievement.