7///THE BATTLE OF BURNSIDE’S BRIDGE AT ANTIETAM, AMERICA, 1862

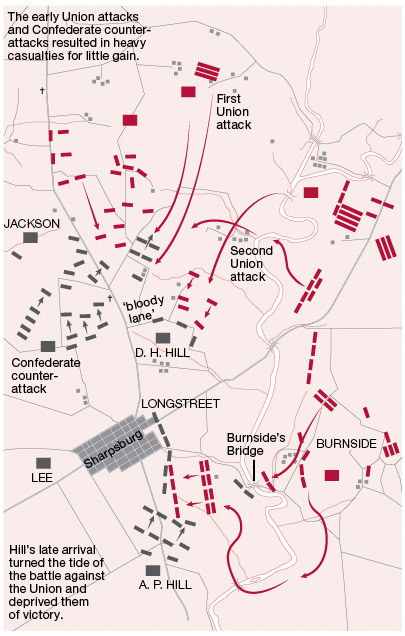

At the Battle of Antietam, 17 September 1862, despite the sheer weight of firepower that Confederate infantry and artillery could muster against their Union opponents, the men of Burnside’s Corps hurled themselves across an exposed stone bridge on the southern flank of McClellan’s Union army. They gradually secured the crossing and then drove relentlessly on a narrow front onto the heights beyond. But for the late arrival of Confederate A. P. Hill’s Corps on the field, Burnside’s men, who were only engaged in a ‘diversionary manoeuvre’, came within an ace of winning the Maryland battle against the Confederate forces of Robert E. Lee.

The second autumn of the American Civil War marked the end of an ignominious period for the Union. Despite the high hopes of 1861, their forces had failed to crush the rebellion of the southern states, and in 1862 the Union effectively lost three Virginian campaigns in succession. In the Shenandoah Valley, despite a three-to-one numerical superiority, the Union troops had been outclassed by the manoeuvres of General ‘Stonewall’ Jackson and his Confederate infantry (nicknamed ‘foot cavalry’). Soon after, Major General George McClellan led an army of 100,000 towards Richmond, the Confederate capital, but after a series of battles in the Seven Days’ Campaign he was instead ordered to evacuate the Virginia Peninsula. Finally, Major General John Pope had also been deceived at the Battle of Second Manassas by Jackson and General Robert E. Lee, again despite superior numbers. In early September 1862, Washington, DC, was full of wounded or dispirited Union troops. McClellan was called upon to restore discipline and morale. For all his faults as a commander in the field, not least his excessive caution and procrastination, he did not lack the energy or enthusiasm for creating armies. In just four days, McClellan had reinforced and reorganized the Army of the Potomac to deploy seven corps of 90,000 men, with a further 70,000 in fortifications.

Unaware that the Federal army had been bolstered, Robert E. Lee decided to take the offensive. The plan was to feed his Confederate forces in northerners’ fields, rather than in the impoverished south, and then to inflict a decisive defeat on the Union. This would force President Abraham Lincoln into a negotiated peace, and perhaps convince the states of Europe to intervene on the Confederates’ behalf. Lee advanced quickly with five columns, but McClellan had reorganized so swiftly that he was actually marching to intercept him. Lee was also unaware that a copy of his plans had fallen into Union hands, meaning that McClellan was able to predict with some accuracy where each of the Confederate columns would be. His plan was to interdict them, defeating each one in turn.

Lee’s forces had, however, fallen behind their march schedule, and Confederate cavalry patrols alerted Lee to the presence of the Union Army. Fighting a series of short, sharp actions in the uplands to the east of the Potomac River in Maryland, Lee withdrew his columns and concentrated in two locations: Harper’s Ferry and Sharpsburg. He had with him just 18,000 men but was confident he would be joined by Jackson’s reinforcements. Lee’s flanks were anchored on the Potomac and his front was protected by the Antietam Creek. While his men were concealed in the folds of the rolling ground, farms, stone walls and woodland would offer cover.

When he arrived on 15 September, McClellan surveyed the Confederate position, but, despite having 75,000 men under his command, he was inclined to believe intelligence reports that suggested the army opposite numbered up to 100,000: a wildly exaggerated estimate. The arrival of Jackson’s 9,000 Confederate troops on Lee’s left the next day, coupled with field obstacles and the Confederate dispositions, gave an illusion of strength that did little to change this impression. In the centre of the Confederate position, Major General D. H. Hill’s Division occupied a sunken lane as a natural entrenchment, and used wooden stakes to create a line of abbatis. On the right of Lee’s line, Major General Longstreet’s Corps, with the bulk of the Confederate artillery, was ordered to hold all the southern and eastern approaches, and this mass of men also reinforced the impression of a well-defended line.

When McClellan had finally decided to commence an attack at 1400 hours on 16 September, he ordered a preliminary bombardment from a number of his batteries, but the cannonade was far from effective. Consequently, he looked to make a flanking attack against Lee’s left, while pushing Major General Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps in from the south. McClellan’s cavalry and two corps were held in the centre to exploit the success of either flank. It took so long to get the various formations into place that little more than skirmishing occurred that day. Darkness and heavy rain interrupted any major action. To conceal their positions, McClellan ordered that no campfires be built and so the Union troops spent a miserable night in the soaking rain, knowing that, after dawn the next day, they would be thrown against the Confederate battle-lines. As dawn broke, Lee received a further reinforcement of 10,000 men, bringing his total strength to 37,000.

The battle recommenced at 0600 hours, with Union guns pounding the Confederate lines. As the main Federal attack got underway in the north near Dunker’s church, the Union artillery played havoc with Confederate infantry stationed in a cornfield and swept them away. The offensive seemed to be going well, and the Union troops marched in pursuit as the survivors of the original Confederate line fell back, but moments later Jackson’s men appeared and their dauntless counter-attack soon had the tired and astonished Union troops reeling back across the ground they had won. Each of the Confederate regiments, however, tended to push too far, and once again Union artillery cut them down in swathes. At this juncture, a new Union corps, the XII, threw the Confederates back, but, just as it advanced, it too was cut to pieces. Inexperienced soldiers broke and ran, while hundreds more were pinned down near Dunker’s church, unable to get forward or withdraw without suffering terrible losses.

On the Confederate side, losses were just as stunning. Captains took command of shattered brigades, and some regiments were reduced to a handful of unwounded troops. Yet, miraculously, when the fresh Union II Corps started to march up and cross the Antietam Creek, Jackson’s exhausted men rallied and took what cover they could find to pour fire into the oncoming Union masses. The arrival of some Confederate brigades previously held in reserve on the flank of the Union advance meant that the Federal soldiers suddenly found themselves in a crossfire; in twenty minutes 5,000 were killed and wounded, and several units disintegrated entirely.

Despite this, elements of II Corps pressed on towards the Confederate centre where Hill’s Division were manning the sunken lane. The Union troops advanced with parade-ground precision, and were allowed to come to within short range before the Confederates unleashed their first volley. The Union troops seemed to hesitate only briefly and then resumed their advance. Each subsequent volley produced a similar effect. A Confederate counter-attack at this point broke through the Union line but was itself stopped short by the Union Irish Brigade. This formation of immigrants from New York hurled the Confederates back, straddled the sunken road and poured fire along it, cutting down defenders. The sunken road was soon so choked with dead and dying men that it was later given the epithet ‘bloody lane’.

The Union attack might have pressed on right through the collapsing centre of the Confederates’ lines, but fatigue, the last-ditch resistance of the survivors and the arrival of Lee’s final reserves halted the northerners’ advance. As McClellan pondered throwing his remaining troops against the fragile Confederate defences, he was advised by his corps commanders that their lines had been decimated. Major General Fitz-John Porter, commanding V Corps, pointedly remarked: ‘Remember, General, that I command the last reserve of the Republic.’ McClellan paused and then called off the attack in the centre. He could not have known just how close he had come to victory, but his inherent caution and the advice of his comrades made the decision for him.

The stone bridge across the Antietam Creek in the southern portion of the battlefield was one of those features that seems to assume an importance out of all proportion to its size, and creates an effect of tunnel vision on military leaders. On either side of the bridge, the waist-deep river could be forded, while the narrow span of the bridge – which was just 12 feet (4 m) wide – canalized troops, turning even small numbers of men into a mass that was an easy target for the Confederates dug in on the steeply wooded slopes that lay to the west. Burnside had been ordered south to make a diversionary manoeuvre to support the Union thrusts further north earlier that day, but he had also been instructed to await further orders, and had done so until about 1000 hours. By then, the Confederates had stripped out all available men until just 2,000 remained to watch over the bridge and stream, against 11,000 of Burnside’s IX Corps and 50 guns. In fact, opposite the bridge itself, the Confederates had just 600 men, but they were well entrenched and could dominate not just the bridge but also its approach road, with 12 cannon in place to blast any assault force with round shot and, at close quarters, canister.

When he was finally ordered forward, Burnside decided to send a reinforced division further south to cross at a less well-defended point. This division would then return northwards and clear the Confederate positions from the flank. The Kanawha Division, led by Brigadier General Jacob D. Cox (who also held nominal command of the corps on Burnside’s insistence), was tasked with attacking across the bridge in a direct assault at the same time. At the head of the assault force was the 11th Connecticut, led by Henry Kingsbury, a 25-year-old colonel who was highly popular with his men.

Kingsbury assembled his troops behind a low hill just 200 yards (180 m) from the bridge, and then, on his signal, they rushed forward. Within seconds, withering fire was cutting down these Union skirmishers. Only one company managed to reach the stonework of the bridge. Another plunged into the creek, as bullets ripped up the surface around them. Captain Griswold, their leader, was one of the few to actually get across the stream, only to fall wounded on the far bank. Kingsbury, urging his dwindling command forward, was hit four times and fell mortally wounded. A brigade that tried to follow the Connecticut attack lost their direction and ended up some hundreds of yards to the north of the bridge, and they failed to get across the water at all. Finally a brigade that was assembled on the road ready to make a densely packed charge down to the bridge suffered such heavy losses from Confederate sharpshooters that they were soon pinned down. Those Union survivors who were able melted back to the cover of the hill, having lost a third of their strength in less than 15 minutes of fighting.

By midday, McClellan had ordered that Burnside should make a full assault rather than a diversionary action, and in his exasperation demanded success even if it cost the lives of ten thousand men. Burnside ordered up one more brigade and decided that the vanguard of this new attack was to be made by the 51st Pennsylvania and 51st New York, regiments with good fighting reputations. To aid this renewed assault, Union artillerymen manhandled their guns to the flanks and began strafing the Confederates with canister. If this suppressive fire was supposed to save the assaulting troops, it failed. Within minutes of coming into view of the bridge, the Union infantrymen were dropping in their ranks. The formation broke up and the troops ran forward to try, vainly, to find some cover by the bridge itself. The Pennsylvanians were to the right and some took shelter behind a stone wall, but the New Yorkers, with no cover but a rail fence, were left exposed to the fire of the Confederates entrenched just 25 yards (23 m) distant. For a few minutes, both sides blazed away as fast as they could. Minié balls were splintering the tree trunks and fences, ricocheting from the stonework of the bridge, or crashing into men’s flesh. Lieutenant George Whitman, Union officer and brother of the poet Walt Whitman, wrote that he and his men ‘showered lead’ across the creek. Canister cases exploded from the muzzles of nearby cannon, adding to the blizzard of fire sweeping the space between these two lines of men. The dead and dying lay strewn between, and the wounded tried hopelessly to crawl away, searching for some cover.

In a bloody and inconclusive battle, two of Burnside’s regiments exhibited extraordinary courage under fire and secured a river crossing that, but for the arrival of Confederate reinforcements, would have given the Union Army a decisive victory.

Anxiously, Burnside’s officers looked to the south, hoping the division sent to cross further downstream would return and attack the Confederates’ right flank. No one appeared: the division had found the designated crossing point unsuitable and had been forced to march further away from the fighting. If the bridge was to be carried at all, it had to be done by the Pennsylvanians and New Yorkers themselves.

The intensity of fire had not slackened for an instant. The crack, buzz and sickening thump of bullets finding their mark had gone on for a full 30 minutes, and soon the Confederate soldiers in the front line realized that they were down to their last few cartridges. On the Union side of the river, the situation seemed to be just as bleak. Ammunition pouches were almost empty and there was no chance of getting more across the exposed and fire-swept space behind them.

Then, in that instant, something extraordinary happened. Captain William Allebaugh stood up and dashed forward onto the bridge itself. Behind him came the first sergeant, two colour-bearers and, on their heels, the colour guard with bayonets fixed. The sight of the two colours billowing over the span inspired the Union men and they rose as one to race across the stonework. Soon the entire bridge was filled with charging Federal troops. The Confederate soldiers fired off their final volleys, bringing down more men, but now the blue tide was irresistible: the New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians had been seized by the sheer exhilaration of their own momentum. The Confederates rushed back up their wooded slopes, retreating towards the town of Sharpsburg. The bridge had been carried.

The assault had cost the lives of 500 Union men, while the Confederates left 160 dead on the opposite slopes. As the assault wave crested the first ridge, in a moment of irony, the Union flanking division came into view on their left. More regiments now piled in behind, their shoes marching through the blood of their comrades and raising columns of dust. McClellan was aware that Burnside’s success offered the chance to defeat Lee even though all the other assaults had been checked. This would, however, mean getting several divisions, artillery, ammunition wagons and staff across the narrow bridge. Estimates indicated this would take at least three hours, and Lee was alert to the threat Burnside now posed. While the Union tried to resupply its exhausted assault troops with ammunition and reinforce the bridgehead, Lee used the time to concentrate his artillery, including Parker’s battery, which was made up of young men aged between 14 and 17 (an indication of manpower shortages in the Confederate army). Lee then received word that General A. P. Hill’s Light Division had marched non stop to reach the battlefield, and these crucial reserves might be enough to turn the tide in his favour.

Burnside had also been energetic; his entire IX Corps had assembled on the far bank of the Antietam by 1500 hours, just two hours after the bridge had been taken. Of these, 8,000 men and 22 guns were ready to push on to Sharpsburg and crush Lee. One observer wrote that: ‘the earth seemed to tremble beneath their tread’. The Confederates poured desperate fire into them and the arrival of Hill’s Division at the critical moment caused the Union advance to at first stall, and then to give ground. Some of Hill’s men were carrying Union colours taken as trophies from a depot at Harper’s Ferry and some wore uniforms of a similar blue to the Union army, causing confusion among the troops. As the Union attack broke up, so the Confederate force that had marched or fought all day, also reached the point of exhaustion. Burnside’s men sheltered as best they could just to the west of the creek, with the bridge at their back. The Confederates tried to find cover in the woods and folds of the ground south of Sharpsburg. As darkness fell, the troops expected to renew the bloody encounter in the morning, but the leaders on both sides had learnt that a tactical defence was more economical in terms of lives. Lee took the initiative and decided to slip away, back to the south. Fearing another deception or a counter-offensive, McClellan accepted the advice of those who urged him to stay put.

Burnside’s corps had suffered losses amounting to 20 per cent of their original strength, but they had opened up a crucial flank against Lee and forced him to commit his final reserve. Had McClellan renewed the offensive with the fresh divisions at his disposal, historians agree that he could have defeated Lee. However, this, the bloodiest battle of the entire Civil War, seemed to have sobered all levels of command. It is estimated that, in a single day’s action, the Union had lost 12,500 men and the Confederates 10,000. The nature of the fighting around Burnside’s Bridge seemed to characterize the entire battle, and the incredible courage of the combatants, particularly the 51st Pennsylvanians, and 51st New Yorkers, was a remarkable success of human will against the sheer firepower of modern weaponry.