10///CHRISTIAAN DE WET AND BOER RESISTANCE, SOUTH AFRICA, 1900–2

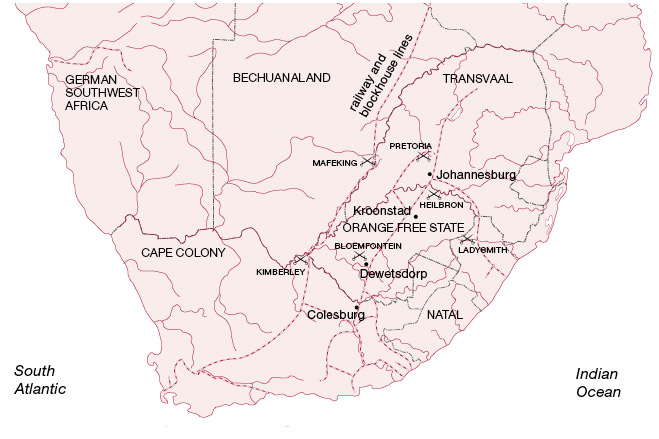

An epic of endurance and determination, the bittereinders (bitter enders) of South Africa maintained a guerrilla campaign against vast numbers of British colonial forces and forced them to reach a generous peace at Vereeniging in 1902. The British high commissioner for Southern Africa, Sir Alfred Milner, and the secretary of state for the Colonies, Joe Chamberlain, had begun to grow anxious about the rapid increase in wealth and power of two Afrikaner republics that lay to the north. In 1886, the discovery of gold in the Transvaal acted as a magnet for foreign workers and led to the establishment of Johannesburg. Milner used the denial of civil and political rights to these workers as the pretext for diplomatic intervention. Exasperated by British pressure, the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State declared war on the British empire in October 1899. The Afrikaner generals led a swift invasion of colonial territory, hoping to inflict a sudden defeat that would force the British to make concessions. The British garrisons in Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking, however, held out, denying the Boers their victory. British reinforcements arrived but initially made little headway in their retaliation, even suffering some serious setbacks. Soon even greater numbers were deployed, and by 1900 the British under Lord Roberts were steamrollering their way to the capitals of the two republics at Bloemfontein and Pretoria. Yet, while the conventional phase of the war was coming to an end in Britain’s favour, many Boer fighters refused to accept defeat. They began to form small parties or ‘commandos’ of mounted men, often clustered around a skilful leader, and waged a guerrilla war against the occupation. While towns remained firmly in British hands, rural areas were not controlled. Attacks on colonial depots, outposts and railways increased dramatically towards the middle of the year 1900.

While some of the Transvaalers had despaired, the actions of General Christiaan de Wet and other rebels provided some encouragement. As early as 4 June, De Wet had led his mounted force to seize a much-needed convoy of supplies at Heilbron to the north of the Orange Free State and then, just two days later, he struck an inexperienced battalion of Derbyshire Militia guarding the bridge over the Rhenoster River. Attacking quickly, from various directions, De Wet used the element of surprise to cause confusion within the garrison. He exploited the disorder of the militia, compelling them to surrender, before using their own ammunition to blow the bridge. Several columns were sent to intercept De Wet but they failed to locate him, finding only the trail of destruction he had left north of Kroonstad. The British reinforced the security of the railway lines with chains of defences and armoured trains, but the Orange Free State was beginning to stir, with more men joining the commandos. Roberts decided to send in three converging columns to press the commandos against the mountain ranges around the Brandwater Basin west of Ladysmith. At first the commandos gave ground and some considered using the mountains as a refuge, but others disagreed, believing they might become a trap, where, starved of supplies, the British would pick them off. De Wet argued that they should divide into four groups and break out of the British cordon to the west.

De Wet had persuaded his comrades in the nick of time. On 15 July 1900, under cover of darkness, his men slipped out of Slabbert’s Pass while the British were bivouacking only a day’s march away. Alerted to the move the next morning, the British cavalry and mounted infantry tried to pursue them, but were pinned down by De Wet’s rearguard actions while the Afrikaners got their wagons of supplies safely away. Other Boers were not so lucky and found themselves cornered. Over 4,000 were forced to surrender and it seemed only a matter of time before De Wet and his confederates were tracked down in the same way. In fact, the British columns spent weeks pursuing De Wet, but he would ride, make feints, double back, change direction or fight seemingly at random. Meanwhile, in the western Transvaal, Koos de la Rey and Jan Smuts had ignited their own guerrilla war. Along with 7,000 men, they had based themselves south of the Magaliesberg Range, to the west of Pretoria, making raids across the region. Roberts strengthened the security of Pretoria with more troops and defences but was unable to suppress the guerrillas despite some spirited actions by his more isolated detachments.

De Wet crossed the central railway that ran northwards from the coast to Pretoria in early August, and eventually he reached the Vaal River. His objective was to enable the president of the Orange Free State, Martinus Steyn, to travel north to reach Paul Kruger, the President of the Transvaal, uniting the ‘shadow’ government. Afterwards De Wet planned to resume his guerrilla war, but the British had assembled 11,000 men to the south and intended to press him against one of three lines of defences – the Vaal River, the central railway or the Magaliesberg Range, where a further 18,000 British troops were operating.

Despite the sheer numbers operating against him, De Wet managed to keep one step ahead. He made use of the vast terrain to conceal his force, changing his route frequently. Taking care to look for unguarded gaps between British formations De Wet exploited the slow decision-making process of the larger British army and also strictly enforced a high level of discipline on his troops. A corps of European fighters led by Captain Danie Theron provided some experience in reconnaissance tasks too so that, by 14 August, De Wet had found his way through British lines, reached the Magaliesberg Range south of Pretoria and evaded all the attempts to cut him off. At Magaliesberg, De Wet’s men scaled the mountains, crossing where – as locals described it – ‘only monkeys dare roam’. His reputation for being a will-o’-the-wisp was growing, and it was providing inspiration to an Afrikaner population becoming increasingly bitter about British occupation.

To subjugate the resistance, General Horatio Herbert Kitchener reiterated proclamations against guerrilla activity and sent columns of infantry, cavalry and artillery out onto the veldt to track down and destroy the commandos. The mounted Boers could easily evade the slow-moving columns, and concentrated on picking off isolated parties and picquets. They would quickly ambush and, before the British could react, they would mount up and ride away. The columns could spend days searching fruitlessly, and they found it impossible to bring their greater firepower or numbers to bear. The Boers seemed to vanish and the British forces found themselves striking out at thin air.

The need to live off more meagre supplies and inflict as much damage as possible in more locations led De Wet to break up his commando into smaller fragments that could fight independently. The tactical merits of the guerrilla campaign were not in doubt, but from a strategic perspective it was difficult to see how the commandos could succeed. It is true that their effect was psychological as well as actual: they could keep the flame of resistance alive, but their chances of bringing the British to the negotiating table seemed very slim indeed. Moreover, by waging war in such a manner, the commandos risked losing the protection of the laws of war. When Lord Roberts handed over full command of the campaign to Kitchener, it seemed likely the British would take stricter measures against the Afrikaner population.

Realizing that the Boers were living off the support of sympathetic civilians in remote farmsteads, Kitchener decided to clear the veldt, herding as many civilians as possible into concentrated internment camps. Here they could be fed and housed, but also isolated from the commandos. The early experiments were not a success. In the camps many families lost women and children to epidemics of measles and mumps. Myths grew up that the British were deliberately trying to kill off Boer civilians, but it was really a matter of health, hygiene and inadequate organization. The clearances – which also involved the destruction of property, the confiscation or slaughter of livestock and the seizure of crops – not only caused an outcry in Britain but also persuaded the embittered commandos to fight on. Their cause, of resisting British occupation to the end, now seemed even more just. From a practical perspective, the re-housing of the civilians actually freed up the commandos: once the camps became better organized and the mortality rate subsided, many Boer fighters were confident that their families were protected.

The fighters were nevertheless confronted by the problem of logistics. While much of the veldt provided grazing for the horses, there was a shortage of rations for the commandos and ammunition for their German-made Mauser rifles. The Boers therefore took to following the British columns, gathering ammunition and tins of food that had been dropped by tired or overburdened troops. They also made daring raids to secure British Lee-Metford rifles and the food supplies they so desperately needed. By the end of the war, most Boers were armed with British weapons.

Unable to swat the commandos using lumbering columns, Kitchener devised a new strategy. He divided up the landscape into a series of gridded zones, each partitioned by barbed-wire fences and overlooked by hundreds of blockhouses. These fortified emplacements were garrisoned by a handful of troops equipped with communications equipment, food and ammunition, and they were positioned parallel to railway lines along which armoured trains steamed. The trains were mounted with searchlights and machine guns, and carried complements of reinforcements. As the fences snaked across the landscape, the commandos were pushed into smaller and smaller zones. Their freedom of movement was suddenly restricted and raiding became much more hazardous. To flush out the insurgents, Kitchener devised ‘drives’, with infantrymen spread in extended order over vast distances, marching steadily towards the fences and blockhouses. The aim was to crush the remaining insurgents in a great vice. The columns were scrapped; cavalry and mounted infantry units provided the British with more mobility.

In August 1900 De Wet had escaped at the Magaliesberg, but when he resumed attacks on the central railway he was repulsed at Frederikstadt and then hunted by a mounted British column led by Major-General Knox. When De Wet and Steyn met, settling down in a laager (defended camp) while laying plans to take the war into the British-held Cape Colony, they were surprised by part of Knox’s column in a dawn attack. Colonel Le Gallais, the British commander, was wounded in the assault but his men continued the attack. Initially De Wet fled but he returned to assist the troops left behind in a four-hour gun battle. As De Wet tried to get into action, more British mounted infantry arrived, and he was driven off. All De Wet’s weapons and wagons were lost, and 100 of his men were taken prisoner, wounded or killed.

Despite this, De Wet was undeterred. He quickly recruited 1,500 men and headed for Dewetsdorp, a settlement named after his father. There he made a raid and took with him British prisoners, who had to endure severe privations and brutal punishment. Believing De Wet was heading for the Orange River, Knox was again in pursuit. De Wet just managed to keep ahead, hiding in the broken country and moving at night to evade mounted patrols. He drove his men hard, denying them any form of baggage except rifles and ammunition. Although he was ostensibly conducting a guerrilla campaign, he was, in effect, really a fugitive on the run. It was at this point, however, that the commandos still in the field decided to play a strategic ace. They would send a number of groups into the Cape Colony to persuade the Afrikaner population there to rebel against the British. De Wet would take 2,200 men into the Cape itself and ride for Cape Town once the rebellion was underway. Just as Kitchener was being forced to combat a series diversionary raids in the east, he learnt through his intelligence service of the projected ‘invasion’ of the Cape. On 27 January 1901, Kitchener formed 12 columns and rushed troops along the railways that followed the Orange River. The De Wet hunt was underway in earnest.

De Wet used scouts far ahead of his main force to ascertain where the British were strongest, and from this discovered the newly reinforced line. Employing all his skills of deception and fieldcraft, he took the bulk of his men across the Orange River near Colesburg, though the remainder refused to leave their homeland on what they saw as a fool’s errand. Only 15 hour’s ride behind De Wet, the British were soon alert to the crossing. More men took up the chase, including a force of Australians and New Zealanders eager to prove their worth. The pursuers forced De Wet to turn north but heavy rain hampered all movement, with veldt trails turning to muddy morasses, but De Wet drove his men even harder and eventually returned to his westward course. Yet attempts to join up with other commandos failed because of the British columns now swarming into the threatened area. Kitchener deployed 15 more formations along 160 miles (260 km) of the Cape railway. Each one was ordered to sweep westwards and, if it lost contact with the Boers, to return to the railway line to be redeployed further south. This gave the British formation a series of prongs that threatened to cut off De Wet, while the rest of the columns marched southwards.

With his men exhausted by the endless forced marches through the night, the atrocious weather and the cloying mud, De Wet realized the danger he was now in. He had no alternative but to turn back. The problem was that he now had to track eastwards along the southern bank of the Orange River, caught in a quadrangle formed by three increasingly reinforced railway lines and the raging river. Each drift, or ford, had been rendered impassable by floodwaters. On 24 February, he at last found a drift that was relatively unguarded and that the horses could swim. The Boers were pursued for another two weeks but just managed to stay ahead until the British lost the scent in mid-March.

Afrikaner guerrilla resistance developed across Transvaal and Orange River Colony after British victories. Commandos evaded British forces to strike at railways and settlements so successfully that major hunts were made for their leaders, including Christiaan de Wet.

De Wet had managed to traverse 800 miles (1,300 km) of territory and tie up 15,000 British and imperial troops, but had failed to ignite the expected Cape Dutch rebellion. His men, moreover, were worn out by the experience and vowed never to attempt to resurrect the plan. De Wet went to ground, dispersing his men to avoid capture, while other commandos did their best to continue to attack isolated detachments and hinder British forces. Their only hope now lay in staying in the field long enough to convince the British the campaign was no longer worth the cost.

In fact Kitchener continued to improve his defensive railway lines and extend wire fences and blockhouses across the countryside. Each area was still being subdivided into smaller areas to limit the remaining commandos’ freedom of movement. Blockhouses appeared in prefabricated form and were quickly assembled, sometimes at intervals of only 200 yards (180 m). Eventually there would be 3,700 miles (6,000 km) of fencing and 8,000 blockhouses, guarded by 50,000 troops and 16,000 African levies. The British also kept up their night raids and continued to scour the country with columns. In July 1901 the entire Free State ‘shadow’ government was captured, and in August Jan Smuts’ attempt to make another incursion into the Cape (while managing to stay intact and ahead of the British) nevertheless failed to elicit strong support. By October, there were 64 British columns operating against the remaining commandos, and each column had a mounted element that could set off in pursuit, freeing itself from the slower-moving supply wagons and their infantry escorts.

The commandos had pledged to fight to the ‘bitter end’, but the bitter end had now come. Supplies dwindled. Many of their horses died, forcing the Boers to make exhausting treks to stay one step ahead of their pursuers. Hundreds of fighters were captured and made prisoners of war. Thousands of hensoppers (‘hands-uppers’; those abandoning the struggle) surrendered, and many of these disillusioned men then became ‘joiners’ and actually enlisted as auxiliary forces in the British army. By 1902, the majority of Afrikaners were eager to see the war, which had lasted four years, brought to an end. The British government started to talk of a ‘magnanimous gesture’ in their offers of peace and it seemed to be only a matter of time before the remaining commandos were caught, killed or died of starvation.

De Wet had waited until February 1902, when the South African spring had returned, before calling on his men to step up operations, and he made a particular point of avoiding areas close to the new lines of blockhouses or the railways. Roaming deep across the veldt, he was able to surprise the 11th Imperial Yeomanry at Tweefontein. However, the tide was clearly turning: 700 Boer fighters were captured by the new all-mounted columns in night raids (the commandos often moved at night) or in dawn raids, when laagers of tired commandos were easily surprised. Kitchener deployed 9,000 men to sweep up De Wet in a thoroughly systematic cordon operation whereby a line of mounted men would patrol across the veldt, searching every location, before the entire line set off again. At night, the lines would dig entrenchments and wait for the Boers to try and make a breakout. Twice De Wet did precisely that, the second time using a charge of 1,000 fighters and a stampede of cattle to pierce the British line. Yet De Wet had lost 1,200 men in the encounters. Many more were now without horses, trudging on foot mile after mile, anxiously glancing behind them for signs of mounted British pursuers. De la Rey assisted the hard-pressed De Wet by stepping up attacks further west, and making spectacular assaults on well-armed columns, but the erosion of commando numbers was obvious. When the British offered negotiations, it was clear that the opportunity had to be taken.

De Wet and Steyn represented the most diehard opinion among the Afrikaners, with De Wet consistently opposed to any talk of giving up the independence of the two Boer republics. Others, including Smuts, argued that it was no longer a case of fighting to the bitter end, for the bitter end had come. Steyn resigned and De Wet became the acting president of the Orange Free State. Bolstered by the views of his remaining fighters, he maintained his implacable opposition to any compromise with the British, until his was the only voice left not in favour of peace. Finally, a personal appeal from Louis Botha and De la Rey changed his mind, and he accepted the British peace offer, thus ending the war.

Embodying the determination of the Afrikaners to sustain their independence and to resist to the end, De Wet had exhibited perhaps the greatest persistence of all the famous commando leaders. Critics argued that he was really famous only because of his escapes, rather than his ability to change the course of the war, however his real achievement was to keep the flame of resistance alive despite overwhelming odds. That he did so with skill, ruthlessness and devotion to a cause only increases that prowess still further.