12///THE BATTLE OF WARSAW, POLAND, 1920

The Battle of Warsaw marked a turning point in the course of the Polish–Soviet War (February 1919–March 1921), and it is often attributed with having defeated a communist offensive that otherwise would have rolled across Europe. The Spartacists (a German communist group led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht) had already established a correspondence with Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks in Moscow and were planning to synchronize a coup d’état with the arrival of Red Army troops. There were communist revolts breaking out in Berlin, Munich and Budapest. Red revolutionary flags had been hoisted by disaffected German soldiers, angry at the outcome of the First World War. In Britain, the decision to assist anti-communist forces with an armed intervention in Russia led to protests among some British workers. When the government in London offered to send military supplies to Poland, the Trades Union Congress threatened a general strike. French socialists were just as militant. The left-wing newspaper L’Humanité announced: ‘Not a Man, not a sou, not a shell for reactionary and capitalist Poland. Long Live the Russian Revolution! Long Live the Workmen’s International!’

In Russia, Lenin and the Bolsheviks had argued for some time that communism could not survive if it was confined to one country. Leon Trotsky, commanding the Red Army, spoke of the need for a world revolution. Lenin believed the more advanced industrialized economies of Western Europe were ripe for revolution, and that the Reds had only to march through Poland to link up with the revolutionaries there. Nikolai Bukharin, a leading writer for the communist newspaper Pravda, declared that the Red Army should push on ‘right up to London and Paris’. The vast size of the Russian population had always created concern in central Europe about the military potential of their eastern neighbour, and, despite the defeat of the Russian armies in the First World War, the prospect of hundreds of thousands of ideologically enthused communists linking up with the Russian armed forces (regarded as a ‘steamroller’) was alarming to the European elites. European workers appeared to be seething with discontent and ready to revolt.

To make matters worse, the Poles and Ukrainians – who had enjoyed some initial successes against the Russians in early 1919 – were in full retreat by the following summer. Some 800,000 Red Army troops had overcome the bulk of their ‘White’ anti-communist enemies within Russia, contained the foreign interventionist forces from the West and were pursuing the Poles across the Steppes towards Warsaw. They were moving at a remarkable speed, covering about 20 miles (32 km) a day, which gave the Poles barely any chance to regroup. The first Polish defensive line, in the Ukraine on the Auta River, was pierced in four days of bitter fighting at the beginning of July 1920. The second attempt to stem the Russians took place along a line of old German trenches in mid-July, but there were simply too few Polish troops to hold every part of the line in strength. Spread across a front of 200 miles (320 km), the Russian forces infiltrated, bypassed and continued to press the Poles back at every point. General Semyon Budyonny’s 1st Cavalry Army swept deep into the Polish rear and captured the Warsaw neighbourhood of Bródno. For a time it appeared the Polish forces would be enveloped and swallowed up. A Polish attempt to regroup on the River Bug was initially successful and the Russians were held for a week, but, while the Poles planned a counter-offensive, the fortress of Brest-Litovsk – the concentration point of their attack – fell to the Soviet 16th Army as soon as it was assaulted. The Polish army was in disarray. Soldiers in rags and bare feet were in full retreat. Defeat seemed imminent.

General Tukhachevsky, who commanded the Soviet armies of the Northwest Front, exclaimed to his troops: ‘To the West! Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to worldwide conflagration. … Onward to Berlin over the corpse of Poland!’ Similarly enthusiastic reports were being issued in Moscow. Indeed, so self-evident did the victory seem that Josef Stalin, the chief Political Commissar for the neighbouring Southwest Front, took a portion of the Red Army to seize Lvov in the hope of gaining greater recognition. The rest of the Southwest Front armies marched towards the region of Galicia as planned, but Budyonny’s cavalry also disobeyed instructions and sought to have the glory of entering Lvov first. This decision was to prove costly to the Soviets. Instead of covering the southern approaches to Warsaw as planned, Budyonny and Stalin had left a gap that the Polish army could exploit. Of equal magnitude was the breaking of Soviet ciphers, which gave the Poles access to Soviet signals traffic. Not only did this allow the Poles to read diplomatic messages, but it also helped them determine where and when Soviet formations would move, as well as their strengths and their armaments. It was through these decrypted intercepts that the Poles learnt of the gap that had appeared in the Russian advance.

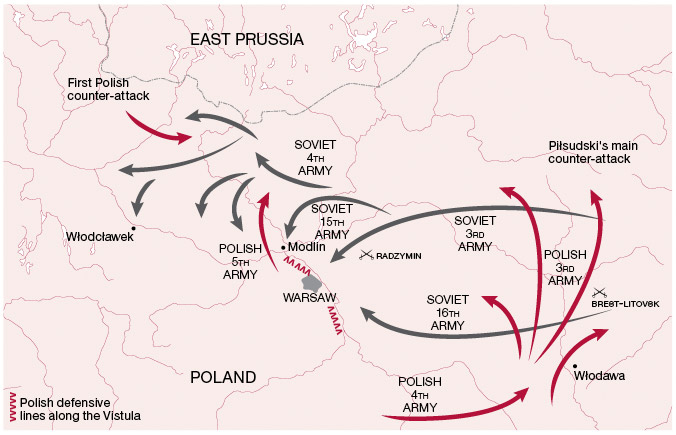

General Józef Piłsudski, commander of the Polish forces, was well aware of the critical nature of the military situation, but he conceived a bold plan to save Warsaw. The scheme was so daring that even some of his subordinates did not believe it could work. It seemed a desperate last gamble. First, the Polish army had to be reinforced rapidly. Fortunately, as the army fell back, its lines of communication shortened, making the passage of information and supplies easier. Fresh forces could be called up. Once a defensive line had been stabilized, the Polish forces were deliberately to fall back in good order across the Vistula River to draw the Soviets on towards Warsaw. Of all the troops available, Piłsudski intended to keep a quarter to the south ready for a strategic counter-offensive that would cut across the axis of the Russian advance. To the northwest of the capital, the Polish 5th Army would hold back until the Russians were fully committed to their attack, then they too would be unleashed, cutting into the rear of the Soviet lines of communication.

Piłsudski concentrated a corps of 20,000 men as the main fist of his southern counter-offensive. He selected the best of his units for this critical task, and reinforced each of the wings with elements of the Polish 3rd Army and 4th Army. Positioned along the Wieprz River, they were poised to strike. They were still gravely outnumbered, however. If the Soviets detected them, and they were engaged, the entire plan would fail. A number of officers feared that this would happen as the Russians advanced on a broad front. Some even condemned the plan as ‘amateurish’. Moreover, such was the haste in which the plan was conceived that logistical arrangements had not been completed by the time the battle began. Units were attempting to reorganize within a days’ march of the advancing Russians, and many were still under strength. Often units were also equipped with weapons from a variety of countries, creating confusion in ammunition resupply.

Fortunately for Piłsudski, the Soviets on the southern side of the advance had lost contact with the Polish forces in front of them, and they did not detect the build-up. Tukhachevsky’s plan was simply to advance towards Warsaw, seize river crossings north and south of the city, and then launch the main offensive from the northwest, curling around the city to the north and cutting off the Polish supply routes from the coast. The southern flank was to be held by the Mazyr (or Mozyrska) Group, a single infantry division of 8,000 men whose role was really only to maintain a link between the Northwest Front and the Southwest Front.

The Bolshevik Red Army seemed to be unstoppable as it advanced westwards, but General Piłsudski conceived a bold plan to use smaller, more agile divisions against the vast and less manoeuvrable Russian forces.

The initial and rapid successes of the Red Army as it strode forward, however, unnerved Piłsudski. Four Russian armies were moving on to the capital, and the fall of Radzymin, a fortified town just a few miles from the city’s outskirts, forced Piłsudski to bring his entire plan forward by 24 hours. On 12 August, Polish and Russian forces each attempted to take control of the area around Radzymin. Fighting continued all day and night, and the Poles waited until dawn on 13 August to evacuate the fortress of Modlin. The pressure of Soviet numbers was overwhelming. Everywhere the Poles were being forced back.

At this critical juncture, the 203rd Uhlan Cavalry Regiment made a courageous and seemingly suicidal charge. Breaking through the Russian lines they continued into depth and overran the radio command post of the Soviet 4th Army. Realizing that the Soviets in this sector had only one other frequency open, the Polish army sent continuous jamming signals. Deprived of communications, the Russian formation was thrown into chaos.

The Soviets, meanwhile, had reached the capital, and were contesting the suburbs with the Polish 1st and 5th Armies. General Józef Haller, with overall command of Polish forces in the northern sector, realized the gravity of the situation. He knew that Piłsudski’s southern counter-offensive was not ready to be launched, and so he took the initiative – advancing to engage the Soviet divisions that were now crowding into the plains north of the city and heading in his direction. Although outnumbered and outgunned, the 5th Army held the Soviets at Nasielsk between 14 and 15 August. The recapture of Radzymin at the same time lifted Polish morale at a critical moment. With the Russians forces halted, the 5th Army went over to the counter-attack and used all the tanks and armoured cars the Polish army could muster to drive deep into the areas behind the Soviets.

On 16 August, aware that the tipping point had come, Piłsudski unleashed his southern counter-offensive. The Soviet Mazyr Group was crushed by one Polish division and a cavalry brigade, while the other four divisions under Piłsudski’s personal command met no opposition at all. They pushed forward 28 miles (45 km) on the first day, severing Soviet communications and supply routes. On the first night the town of Włodawa was also recovered. By the middle of the second day, the Polish counter-offensive was continuing northwards, slicing its way through the supply system of the Soviet forces and embedding itself 45 miles (70 km) in the rear of the Russian armies. Tukhachevsky realized what was happening and issued orders for the Russian forces to halt and change axis in an attempt to shorten his front, recover his lines of communication and counter-attack. But it was too late. Some units did not get the orders, while others tried to press on towards Warsaw. Some just halted. The result was total confusion. The only Soviet formation to retain cohesion was the 15th Army, which managed not only to extract itself but also to shield the collapsing Northwest Front.

In the north, the Polish 5th Army continued to make progress on its own account. The Polish 1st Infantry Division made a remarkable forced march to cover over 160 miles (260 km) in just six days, placing itself deep in the Soviet rear. The result was that reinforcements for the Soviet 16th Army were intercepted and checked. Deprived of supplies, orders and ammunition, many Russian troops decided to surrender.

Three Russian armies had fallen apart, and their troops were either surrendering or streaming to the east in a desperate bid to escape the pursuing Polish forces. The Russian 3rd Cavalry Corps continued advancing and managed to cross the border into Germany. There it was halted and, given that hostilities had not been declared against Germany, it was interned. Some 15,000 Russian soldiers had been killed in Piłsudski’s manoeuvre, with a further 10,000 wounded and 65,000 taken prisoner. Polish losses were 4,500 killed and 22,000 wounded. The Poles also captured over 230 artillery pieces and more than 1,000 machine guns. But the most important result was the failure of the Bolshevik offensive. While supremely confident of victory in early August, the Russians had been driven back on every line by the middle of the month. After the battle, Tukhachevsky tried to rally and reorganize his armies. He formed a defensive line along the Niemen River, but was broken again in a six-day engagement in September. With the Bolshevik forces hurrying rearwards, Moscow readily accepted the ceasefire brokered by France and Britain.

Piłsudski had achieved something that most had considered impossible. Heavily outnumbered and with his own forces retreating, he had executed a brilliantly bold, if extremely risky, counter-offensive. The appearance of his divisions from an unexpected direction, and the severing of the Soviet lines of communication, caused utter confusion in the Russian headquarters. The loss of cohesion and momentum, combined with the continuing pressure of the Polish forces, initiated the sudden collapse of the Bolshevik armies, and the Polish counter-offensive at Warsaw gave rise to the belief that Poland had effectively saved Europe from a Bolshevik invasion. The Soviets did indeed abandon hopes for a march westwards into Europe and concentrated instead on the consolidation of power within most of the territories of the former Russian empire. Their expansionism was contained thanks to the daring plan of General Piłsudski, and, as it came to be known, ‘the miracle on the Vistula’.