16///THE DEFENCE OF KOHIMA, BURMA–INDIA BORDER, 1944

The Allied defence of Kohima from 4 April to 22 June 1944 during the Second World War involved battles across a tennis court, intense trench fighting and inspirational courage. It was the ultimate close-quarter battle, fought by an outnumbered British and Indian garrison and a highly motivated Japanese army. Kohima marked the high tide of Japanese military expansion. Over the course of three years, the Imperial Japanese Army had swept British, American, Dutch, French and Southeast Asian forces before them, and had earned a reputation for invincibility.

The Imperial Japanese forces were characterized by courageous frontal assaults regardless of casualties, ritual suicides to avoid capture and defensive battles contested to the death. They were, however, also condemned for ‘illegal’ ruses of war, including booby traps and ambushes, as well as suicide attacks, such as human mines and kamikaze aircraft. At the time the West gave the explanation that this was all just ‘fanaticism’, but this was really an excuse to avoid the thorough analysis of a formidable and determined adversary. In Japanese military culture, many old martial traditions remained embedded in training and doctrine. A rigid form of militarism, derived from ideas of self-discipline in martial arts, reinforced military values as a means of both unifying Japanese people, and provided a framework for their daily thought. Japanese soldiers were inculcated with values that emphasized utter obedience to the Emperor, his officers and all their orders; these values also encouraged self-deprivation, sacrifice, faith, comradeship, physical courage, honour and the desire to atone for shame or failure. Each man was taught to take the view that death, while not necessarily imminent, was inevitable and therefore ought to be accepted quietly whatever the circumstances in which it was presented. Even civilians faithfully recited the military slogan: ‘Duty is weightier than a mountain, while death is lighter than a feather.’ In the army there was a strong culture of competition, driving soldiers to excel against all others and to regard all non-Japanese as inferior, and therefore deserving of defeat.

By the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941, these philosophical values had been developed into the Senjinkun (soldier’s code). In it, duty was elevated to a religious mission. The army, soldiers were told, was the means of bringing about Hakkō Ichi-U (ultimate world unity). Obedience to the Emperor in this endeavour was vital because he was, they believed, a deity. His orders could not be disobeyed since they were religious instructions. Consequently, failure in battle meant a soldier let down not just his comrades, but also the country, the Emperor and the divine mission. The only way to atone for this failure or prevent the situation getting worse was to remove oneself from the mission honourably, that is by seppuku (ritual suicide). The code demanded that enemies were to be treated courteously only if they had behaved honourably: those that surrendered disgraced themselves. The courage of the Japanese in battle was, however, only in part due to this idea of a mission – it was also closely connected to Shintoism. Soldiers who had fallen in battle were deified at the Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo, and it was a widely held belief that they would be immediately transmitted to paradise, where they would enjoy immortality among the gods.

During training, the Japanese soldiers received religious instruction alongside their military tutorial. The seishin kyōiku were a set of religious values or virtues closely tied to the Senjinkun. These values were reinforced constantly through battlefield tours, slogans in mess halls, lectures and visits to museums. From these precepts, the soldiers were expected to cultivate a sense of inner power (the kiai) that united the mind and the will to form an irresistible force. Developing kiai required gruelling training: recruits were beaten for the first few days after arrival to toughen them; there were marches of 50 miles (80 km); tests of endurance; and a spartan lifestyle. A day’s rations, for example, consisted of two portions of milled rice and three servings of tea – the rest was down to improvisation and initiative. The training regime included a strong emphasis on bayonets. As in the West, they were attributed with a moral as well as physical value. Because of the bayonet’s association with close-quarter fighting, it was thought to embody the ‘spirit’ of the attack. Indeed, the Japanese Army was taught that the bayonet charge was always the climax of the assault, and it was thought to foster aggression in each individual. This may explain why, even when Japanese forces faced defeat in the latter stages of the Battle of Kohima, they would attempt to make a final bayonet charge. It was the attitude that made them such formidable opponents. General Hideki Tōjō, the commander of Japanese forces, ordered his troops to fight to extermination, or kill themselves if they failed in their mission.

The Japanese infantry were also taught that infiltration using all the available terrain and rapid movement was preferable to a frontal assault. In a number of battles throughout 1942 and 1943 the Japanese had demonstrated their skill in moving even large formations in this way, encircling the British using jungle tracks, or driving deep behind their lines. But the British had also learnt to adapt to these tactics, and by 1944 they had built up their forces and improved training. There was better coordination between formations, a greater abundance of air power and artillery, as well as more efficient supply systems. Although the terrain lent itself to the envelopment of enemies, the British learnt to fight on even if surrounded, with each unit in a self-contained box formation. In addition, they decided to play the Japanese at their own game and deployed thousands of Chindits (highly trained jungle troops) behind Japanese lines to attack their logistics and disrupt their plans.

After the fall of Singapore in 1942, the British and Indian forces were driven back through Burma at the height of the monsoon, and British efforts to contain or defeat the Japanese the following year remained unsuccessful. In the spring of 1944, the Japanese launched the U Go Offensive across the border of India, initially intending to disrupt the concentration of the Indian Army IV Corps at Imphal. Lieutenant General Renya Mutaguchi, commander of the Japanese 15th Army, believed that if sufficient determination was shown by all ranks, there was the opportunity to break the British resistance in the region once and for all. Plans were therefore drawn up to push into India, and to send the 31st Division to seize Kohima and cut off the routes to Imphal. From Kohima, the division would press on to Dimapur, the main logistics base for the Indian Army in the area. In fact the commander of 31st Division, Lieutenant General Kōtoku Satō, had grave misgivings about the plan and believed that his logistical system would break down under the strain.

On 15 March 1944, Satō’s division crossed the Chindwin River at Homalin and then wound its way along jungle trails until it clashed with elements of the Indian Army covering the northern approaches to Imphal just five days later. The commander of the Japanese 58th Regiment was aware that the Indian 50th Parachute Brigade in front of him at Sangshak was not his primary objective, but he nevertheless resolved to drive them off in order to take the initiative in the campaign. The Japanese must have had some misgivings when it took six days of intense fighting to dislodge the Indian troops. In fact, only when artillery and reinforcements from the 15th Division arrived could the Japanese be certain of success. They had inflicted 600 casualties and overrun the British Indian Army positions, but the whole enterprise had taken up a week, and thus delayed the main offensive.

The intensity of the fighting had alerted Lieutenant General (later Field Marshal) Bill Slim, the British commander of Fourteenth Army, to the scale and direction of the Japanese offensive. It had been widely believed that the terrain and close vegetation would prevent the Japanese making any thrust towards Kohima with a force any larger than a regiment (the equivalent of a British brigade) and consequently it was only lightly held. Steps were soon underway, however, to reinforce Imphal. The 5th Indian Division was flown in from Arakan, where it had just defeated the Japanese at the Battle of the Admin Box. Elements of other units were flown or transported by rail to Dimapur. These included the 23rd Long Range Penetration Brigade of the famous Chindits, whose task it was to harass the right flank of any Japanese advance.

Surrounded, fighting daily at close quarters and practically overwhelmed, the small garrison of Kohima held up the Japanese offensive into India with inspirational courage and determination. Their effort helped turn the tide of the war in Southeast Asia.

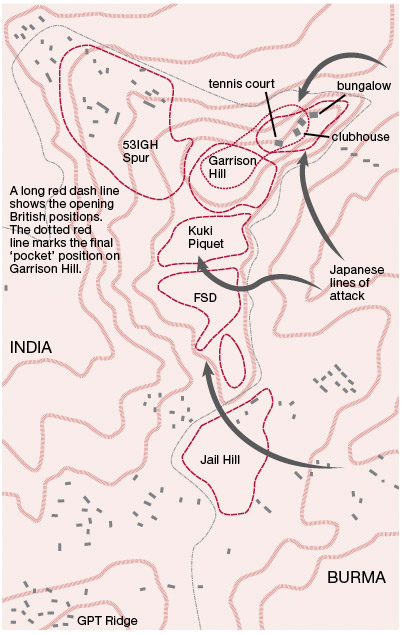

The Kohima ridge feature dominated the road that led from Dimapur to the three British divisions holding Imphal, and it was clear that if the Japanese were able to capture this position then the way into India would be open. The settlement at Kohima was also the administrative centre of Nagaland in northeast India, and on the ridge itself stood the Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow, with clubhouses and a tennis court on the terraces above. Many of the slopes were covered in thick vegetation, so the ridge was hardly ideal for defence. To the north of the ridge lay a settlement known as Naga Village, dominated by two features known as Treasury Hill and Church Knoll, while to the south lay two more areas of high ground called GPT Ridge and Aradura Spur. Along the main ridge, local units had labelled their positions as Garrison Hill, Kuki Piquet, 53IGH Spur and FSD. In front of the position, to the east, men of the local Assam Regiment were ordered to make a delaying action.

On 1 April, the leading formations of the Japanese 31st Division made contact with the Assamese picquets and quickly overran them, bundling the surviving troops back towards Naga Village. The Japanese then made a reconnaissance of the ridge, and began concentrating their units to the north and south. While the 4th Battalion, the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment took up defensive positions along the ridge, the rest of their brigade soon found itself cut off by a Japanese thrust to the west of the ridge that had cut the road. This meant that the Shere Battalion (an inexperienced unit from Nepal), logisticians and some troops of the Burmese Regiment made up a garrison on the Kohima Ridge. In total there were no more than 2,500 men – with this number including around 1,000 non-combatant personnel.

On 6 April, the Japanese began what they thought was the final assault on the ridge, firing artillery and mortars with such intensity that the garrison was soon driven into a pocket on Garrison Hill. Continuous shelling blasted the vegetation away and smashed tree trunks to matchwood. Worse, it was found that unprotected supplies of water had been left on GPT Ridge, which had since fallen into Japanese hands. The sole water supply now available to the defending force was a small spring on Garrison Hill that could be reached only at night. Its slow trickle meant that obtaining a few gallons took hours. As the Japanese flanked to the south of Garrison Hill, the dressing stations for wounded men were exposed to gunfire, and, as a result a number of wounded men were hit a second time. Unburied and mutilated remains littered the battlefield.

At the north end of the ridge, the situation was just as serious. Working their way forward, the Japanese managed to get within a few yards of the Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow. There they were halted by a determined defence that forced them to dig in alongside the tennis court, while the British manned their trenches and foxholes opposite. Grenades were hurled into enemy positions and snipers attempted to cut down anyone exposed on the surface – British soldiers taking combat supplies to forward positions were especially at risk, and had to crawl to avoid sniper fire.

Before long, the British soldiers would hear the voices of their adversaries forming up out of sight in the gathering darkness. Fire support would be called for, to smash the Japanese at their forming up points, but the furious attacks would always come anyway with infantrymen yelling, gunfire pouring in. The British troops would reply with long bursts of Bren gun fire, a shower of grenades ‘like cricket balls’ (as one eyewitness described) and rifle fire at the ‘rapid’ rate. The Japanese infantrymen would crumple, fall or be tossed backwards by high velocity rounds and then their attack would waver and fall back. There would be a pause while the Japanese regrouped, then they might try to infiltrate, crawling forward until practically on top of the position, or they might mount another impetuous charge. The Bren guns glowed red after each attack in the darkness, and, after the relief of finding oneself still alive, then began the business of restocking ammunition, pulling the wounded out of the firing line, replacing the killed men, or taking shelter from the renewed Japanese shellfire that followed every assault. Assamese and Punjabi soldiers also took their turn at the centre of the line, absorbing Japanese artillery and mortar fire, and repelling infantry assaults with the same desperate determination.

Airdrops could sometimes bring precious relief, particularly water, medical supplies, grenades and ammunition, but some drops missed their targets and fell into Japanese hands. Snipers shot down those attempting to retrieve canisters suspended by their parachutes from the trees. Water containers were riddled by Japanese gunners before they could be secured.

On 14 April, Colonel Hugh Richards, the commander of the Kohima garrison, made an Order of the Day that was distributed to every sub-unit of the survivors. It gave simple praise to the men for their endurance and deplored the suffering of the wounded. There was a hint that relief might soon come. It concluded with the words: ‘put your trust in God and continue to hit the enemy hard wherever he may show himself. If you do that, his defeat is sure.’

On 17 April, after ten days of fighting, the Japanese made one more gigantic effort to blast the British and their Indian allies from the ridge. They swarmed over the tennis court and secured the bungalow, before readying themselves for the final assault on Garrison Hill. The situation was desperate for the British Indian Army. Positions everywhere seemed to be falling to overwhelming numbers; platoons were in some cases reduced to three men; in one platoon every single man had been wounded at least once. So many had been killed or wounded that further resistance seemed hopeless. Only one of the Royal West Kent’s mortar sections remained in action. Sergeant King, the battalion’s commander, had had his jaw broken by a shell fragment, yet kept his team in action, holding his broken and bleeding face as he did so. Alongside the high explosive, the Japanese fired in phosphorous shells – their terrifying white tendrils of burning chemicals arcing across the hillsides, leaving noxious smoke to conceal the jogging infantry behind. But the survivors refused to give way. Kuki Piquet was captured, which cut the British garrison in two, but still they held on. The British now occupied an area of only 350 square yards (290 square metres). Everyone waited for the next dawn, knowing it could be the day the Japanese fought their way to the summit.

Yet instead of a final attack, the British suddenly received reinforcements from the 161st Brigade, which itself had been relieved by the breakthrough of the 2nd Division. The brigade had to fight their way in, but the air, artillery and armoured support began to turn the tide. The relieving forces advanced across a lunar landscape of craters and trenches, and evacuated the wounded under cover of darkness – still subjected to intense fire even then. By 20 April, the original garrison had been replaced by the British 6th Brigade but, despite this success, the Japanese were still numerically superior and undaunted in their determination to seize the ridge. Several Japanese charges were made against Garrison Hill, and there were recurring episodes of hand-to-hand combat. Kuki Piquet remained in Japanese hands, spanning the ridgeline, but on the northern side of Garrison Hill the situation was changing. During a night attack on 26 April 1944, the British managed to retake the clubhouse above the Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow and this allowed them to look down into the Japanese positions below. A concentration of howitzers, field guns and two 5.5 inch medium guns had supported the attack, as had the RAF, and while this undoubtedly helped to keep Japanese reinforcements pinned down, the British infantry still had to fight for every foxhole and bunker with grenades, rifles and bayonets. The Japanese had spent time deepening and concealing their positions, so that gun slits could be opened and closed. If the British tried to assault through one position, they were immediately caught in the crossfire of others. It was an impossible situation.

Attempts were made to catch the Japanese in a pincer by attacking both extreme flanks north and south. The monsoon rains made progress even more difficult. The soil, when cleared of vegetation, degenerated into a glutinous ooze of cloying mud. Elsewhere, pounding rain turned slopes into treacherous and slippery ramps. Even where British forces could get forward and gain a small foothold, as in the Naga Village, Japanese counter-attacks could still drive them out. In the south, GPT Ridge was taken in a surprise British attack, but it proved impossible to capture the entire position in one go, and so a see-saw struggle of bitter close-quarter fighting continued after the initial success. Taking a single hill or ridge back from the Japanese became an epic.

It required a week of intense fighting and heavy casualties to recapture Jail Hill, not least because the Japanese had dug in machine guns on the reverse slope of GPT Ridge that could target any attackers as they scaled the adjacent hill feature. As each of the ridges fell, only Japanese entrenched in the tennis court and garden below the Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow held out. On 13 May, the British used a bulldozer to drive a new track to the summit, and up this soldiers hauled a single tank. The tank went into action alongside the 2nd Battalion, the Dorsetshire Regiment; together they blasted each Japanese position in turn at point blank range. It was a curious finale to the battle: a tank firing its main armament into the apertures of one of the most confined battlefields in the world. Wreathed in the smoke of the smouldering bunkers were the sweating, muddy and exhausted British troops in their drab olive-green uniforms. They were tired, but relieved that, at last, the Kohima Ridge was theirs again. Nearby, looking alertly over the parapets they had hastily constructed, were the Indian troops of the 33rd Infantry Brigade – men who had fought for every yard of the Kuki Piquet and the FSD and DIS ridges.

On 12 May, Naga Village had also been attacked but it was not until the 16th that it was finally cleared. The Japanese troops were determined to fight on, but – as Satō had feared – their logistical system had broken down entirely. British special forces were operating on the Japanese right flank, harassing them, while the RAF did their best to disrupt Japanese resupply efforts. The Japanese were also pursuing too many objectives, and it was not clear whether Imphal or Kohima was the main target. The Japanese withdrawal from the Kohima area began on 1 June, when their supply situation had entirely collapsed. The British began to push their assailants further back, and the forces from Kohima and Imphal linked up on 22 June.

Some 4,064 British and Indian troops had been killed at Kohima, but they had inflicted losses of over 5,700 on the Japanese. More importantly, they had broken the mystique of the Japanese soldier. British and Indian troops still respected them, but the Imperial Japanese opponent was no longer a superman able to live off the jungle and strike with impunity from every direction. The Allies at Kohima had proved that the Japanese could be beaten, and decisively. The special forces teams had shown that they could match the Japanese in their jungle skills and ability to infiltrate enemy lines. The British and Indian soldiers had demonstrated they too could take heavy losses, make spirited attacks and sweep their enemy from their positions. Strategically, the losses the Japanese suffered, physical as well as psychological, meant the stage was set for the liberation of Burma and Southeast Asia. It took less than two years to drive the Japanese back to southern Burma and retake Rangoon, all the while inflicting a series of crippling defeats on them. While the Pacific War ended with the use of atomic weapons against the Japanese mainland, we should not forget that Southeast Asia was retaken the old-fashioned way, with the right tactics, sound logistics, sheer guts and determination.

Field Marshal Slim, Commander 14th Army, later wrote: ‘Sieges have been longer, but few have been more intense, and in none have the defenders deserved greater honour than the garrison of Kohima.’ Kohima was the turning point in the Burma campaign. If the ridge had been lost, the route to India would have been open and the situation for the Indian Army would have been critical. The defence of the ridge broke the tide of Japanese expansion, wrecked their ability to rely on movement to maintain their supplies, forced them onto the defensive and smashed the myth of their invincibility. A simple memorial was erected to commemorate the efforts of the British 2nd Division in this battle, its timeless epitaph reads: ‘When you go home tell them of us and say / For your tomorrow, we gave our today.’