18///THE DEFENCE OF THE GOLAN HEIGHTS, ISRAEL, 1973

Stung by a crippling defeat in 1967 during the Six Day War, the Arab states of Egypt and Syria were eager to take their revenge against Israel and wipe it from the map. Steady progress had been made with the rearmament of their armies thanks to Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc support, but Israel enjoyed the backing of the United States and obtained its military hardware from the Western nations. The Middle East was engaged in an arms race, fully aware that a conflict would erupt at some stage. Throughout 1973 Cairo radio was full of anti-Israeli rhetoric, and there were other signs that the Egyptians were preparing for a confrontation. Israel’s Prime Minister, Golda Meir, was not enthusiastic about launching another 1967-style surprise offensive as a pre-emptive strike. Her Defence Minister (and hero of the Six Day War), Moshe Dayan, also advised caution. The alignment of world superpowers behind the Arab and Israeli adversaries had the potential to earn the opprobrium of the international community, or even precipitate a major war. Yet Egypt, Syria and their Arab allies continued preparations. Their plan was to launch a surprise attack, with Egypt heading east across the Suez Canal and seizing the western Sinai, while Syria attacked Israel from the north to overrun the defences on the Golan Heights. To add to their advantage, the Arab states would strike during the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur.

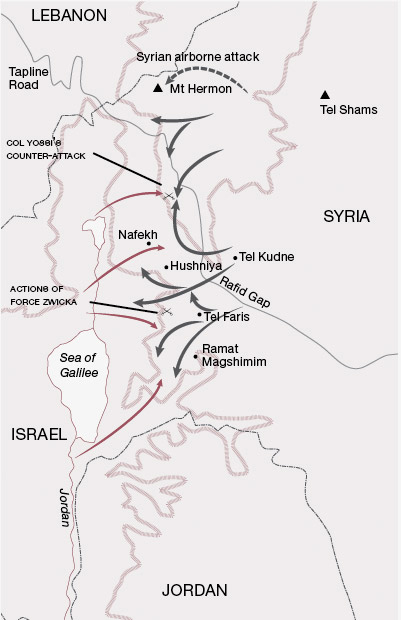

The Golan Heights dominate the entire border of Israel and Syria, and command of these uplands not only controls northern Israel but also offers a straight avenue to Damascus, giving the area strategic importance to both countries. Stretching for 24 miles (40 km) to the east of the River Jordan, the hills were dissected by five key roads running east–west, as well as two routes that traversed north to south. The Syrians deployed five divisions to carry out their planned offensive: the 7th Infantry Division was to advance parallel to Mount Hermon, the highest point on the hills, while to their immediate south, the 9th Infantry Division would push into the Israeli centre. The main attack would be delivered by the 5th Infantry Division in the area known as the Rafid Gap, pressing west and southwest towards the River Jordan. The 3rd Armoured Division and the 1st Armoured Division would lead the assault, and also support the infantry. In addition, waves of aircraft would strafe Israeli positions, knock out their tanks and interdict their reinforcements. The Syrians could muster 1,000 artillery pieces and 1,500 tanks to lay down suppressive fire. Many of these vehicles were the latest Soviet models, such as the T-62 with a 115 mm main armament. The Russians were particularly eager to see how their new equipment performed in these favourable conditions. The Syrians believed it would take them just 36 hours to overrun the entire area.

The Israelis were seriously outnumbered. On the Golan Heights, there was a network of 17 small concrete observation posts manned with garrisons of up to platoon strength, some possessing a troop of three or four tanks. Initially there had been only 50 tanks along the whole front, but the prospect of war meant that reinforcements had been mobilized, bringing the total to 150. This was still a meagre force to face 1,500 armoured vehicles. Fortunately, the Israelis had the rugged and battle-tested American M60 and British Centurion to confront the Soviet-built armour. There were, however, just 60 guns distributed along the 45 mile (70 km) line, and the only personnel for the defence of this strategically important zone were the 7th and 188th armoured brigades.

The Syrian offensive began at 1400 hours on Saturday 6 October with an overwhelming artillery barrage and air attack that lasted almost an hour. Shell after shell plummeted onto the Israeli strongpoints, detonating with an ear-splitting crash, the explosions tearing up the soil and vegetation. Syrian tank commanders watching the debris and columns of smoke could hear the crump of explosions above the roar of their engines, and they started towards their objectives under cover of the bombardment. Meanwhile, Syrian commandos landed by helicopter around the summit of Mount Hermon and dashed up to the gates of the radar station located on the vantage point. The gates of the outpost were defended by only 14 Israelis, so the Syrian special forces battalion was able to work its way forward under cover of machine-gun fire, overrun the incomplete trench system and fight their way into the bunkers. The tiny garrison was soon wiped out.

As Hermon was being captured, the lead elements of Syria’s 3rd Armoured Division and the 7th Infantry Division engaged the Israeli 7th Brigade to the north of the battlefield, and the main Syrian thrust got underway at the Rafid Gap. Here the Israeli 188th Brigade, with its 57 tanks, faced 600 Syrian vehicles. Every few minutes, Syrian or Israeli armour would be hit and explode, while the other tank crews tried desperately to manoeuvre into the best-protected firing points with the largest fields of fire. They worked their guns feverishly, conscious that survival depended on spotting the enemy and engaging him successfully before they were themselves hit and blown to oblivion. The sheer violence of the fighting reflected the intensity of modern armoured warfare: rounds slammed into hulls and turrets, tearing vehicles apart; flames burst from stricken tanks; and black, oily smoke poured across the battlefield. Amid the inferno, survivors who had managed to bail out staggered or crawled into whatever cover they could find.

Only a handful of Israeli tanks survived the initial onslaught. Some, already damaged and carrying the bodies of their comrades, had taken shelter to the west of the Tapline Road. There they met Lieutenant Zwicka Gringold, a young officer who had rushed back from leave to join the battle. Gringold cleared the bodies from the decks of the tanks and formed a small composite force of survivors that could take the fight back to the Syrians. ‘Force Zwicka’, as they styled themselves, consisted of just four tanks. As they drove back up the road, every man in that valiant command must have been fully aware of the odds against him. They all knew that their chances of survival were practically zero.

The Syrian 1st Armoured Division was, by contrast, confident of victory. The attack had been developing well all afternoon, and Israeli positions were being steadily overwhelmed and neutralized. Little now stood between them and the Israeli Divisional Headquarters at Nafekh and, beyond that, the Bnot Ya’akov Bridge over the Jordan. It was clear that the Syrians were advancing all along the line, and that it was only a matter of time before they rolled down into the plains to the west.

Gringold had positioned his four tanks to engage the head of the Syrian 1st Armoured Division. As night began to fall, the Syrian tanks were hit again and again. Then, with a boldness verging on suicidal recklessness, Gringold’s tanks drove into the midst of the Syrian units under cover of the failing light. Since Syrian tanks were often not equipped with radios, there was little chance for them to coordinate a coherent defence. The result was chaotic – the Israeli tanks destroying the Syrians around them and causing utter confusion. As the Syrians tried to re-establish some formation, Gringold’s men would fire from a flank, move into another position and fire again. The Syrians weren’t sure exactly what size force they were dealing with, and for 20 hours Force Zwicka kept up its game of cat and mouse. The battlefield was now littered with damaged and burning vehicles. Some of Gringold’s men were forced to abandon their own tanks and find others to continue the fight. Eventually, Force Zwicka was reduced to just one serviceable vehicle, but still the survivors would not give up. The security of northern Israel depended on them.

By first light on the following day, Sunday 7 October, the Syrian 1st Armoured Division was ready to continue its advance. Israel’s 188th Brigade was all but wiped out. The last few tanks, directed in person by the Brigade’s commander, Colonel Ben-Shoham, stood their ground on the Tapline Road, fighting to the death. Over 90 per cent of the brigade officers were killed or wounded during those 24 hours, sacrificing themselves to buy time for their comrades behind. They were determined to take as many Syrians with them as possible.

The Israelis knew that time was of the essence. Men and tanks arriving from their mobilization points drove straight into battle. Units arrived piecemeal, but the objective was simply to stem the Syrian tide and resist with whatever they had. There was no sophisticated plan, no scheme of manoeuvre: it was a case of fight or die. The Syrians nevertheless kept rolling on towards Nafekh Headquarters. Then, at this critical point, Gringold and his exhausted band in their single tank suddenly burst out of the hills and destroyed the leading Syrian T-62. With high explosive rounds chasing them, they slipped back over a ridge.

On the Golan Heights, at the height of the surprise Yom Kippur War, pockets of Israeli forces were able to survive the initial Syrian armoured offensives. These held the line and provided the spearhead for a more sustained counter-attack that pushed the Syrians back into their own territory.

As the Syrians sent their tanks into the Nafekh encampment, more Israelis joined the defiant resistance. By mid-afternoon, the Syrian attack was stalling, halted about halfway through the complex. The Syrians attempted an outflanking drive to the south at the village of Ramat Magshimim, but this was also blocked. In the south, the Israeli line was holding.

Further north, the Israeli 7th Brigade with a total of 100 tanks was confronted by over 500 Syrian armoured vehicles. For four days and nights the engagement was unceasing. Both sides launched several assaults each day and at least two by night in an attempt to secure the ground. Eventually the sheer weight of numbers decided the outcome. With just seven tanks left intact, the Israelis simply could not prevent the Syrians getting forward at every point and began to pull back. As they did so, they met Lieutenant Colonel Yossi Ben-Hanan with a column of 13 hastily repaired tanks coming up the road. Among the crews were wounded men who had volunteered to rejoin the fight. Bandaged, but defiant, these extraordinary men manoeuvred alongside the seven remaining vehicles of 7th Brigade while the plan for a sudden counter-attack was worked out.

The Syrians, who believed the Israelis to be beaten, were surprised by Yossi’s fierce counterstroke. Thinking the battle was over, the tired and battered Syrian crews were demoralized by this fresh wave of Israeli attacks. Having already lost 500 tanks, a full third of their original strength, and casting an eye over the ‘Valley of Tears’ (as they called the battlefield), the Syrians decided they had had enough. Several Israeli strongpoints, which had held out throughout the four-day battle, reported that the Syrian support vehicles had turned around and were withdrawing – a sure sign the lead elements were also soon to pull back. Then surely the most extraordinary scene in modern armoured warfare was played out – the mass of Syrian vehicles retreated, pursued to the border area by a handful of Israeli tanks.

Soon after, Israel mobilization produced an armoured division under the command of Major General Moshe ‘Musa’ Peled for a counter-attack in the southern sector, where the Syrian forces had not retreated. The fighting was just as fierce as before, but Peled’s new formation began to drive back the invading forces. The Syrians tried to stem the Israeli advance by bringing up the full force of the Syrian 1st Armoured Division. The leading Israeli brigade found itself in a salient between Syrian armoured formations and under attack from several sides. The Syrians, however, were also in a precarious position. Having committed a large portion of their armour and infantry to capture Hushniya, in the centre of the Golan Heights, there was a risk that the success of Israeli counter-attacks on either side could leave the Syrians encircled in a pocket. To make matters worse, the Israeli air force (now restored after initial attacks), had destroyed a number of Syrian aircraft and neutralized several surface-to-air missile batteries. The Israeli pilots now began to turn their attention to Syrian ground forces. To break out of the potential encirclement, the Syrians changed the axis of their attacks towards Peled’s command in the south. Peled was undeterred and made the boldest of decisions: he ordered his leading elements to thrust further eastwards as far as possible into the Syrian depth. The move helped the Israelis gain possession of Tel Faris, a peak that would prove an ideal observation platform for artillery.

The Syrians used the cover of darkness to pull back, regroup and send a force to cut across the Israeli advance. The following morning – the fourth day of the fighting – Peled tried to get forward to Tel Kudne, where the Syrian divisional headquarters were located; however, the action cost him many tanks. The Israelis had more success in reducing the resistance of the Syrians around Hushniya, where not one Syrian tank remained in action at the end of the day. Chaim Herzog (who took part in the conflict, and went on to become a military historian and the Prime Minister of Israel) described the scene in the pocket as ‘one large graveyard of Syrian vehicles and equipment. Hundreds of guns, supply vehicles, APCs, fuel vehicles, BRDM Sagger armoured missile carriers, tanks and tons of ammunition were dotted around the hills and slopes surrounding Hushniya.’ Still outnumbered, the Israelis now drove the Syrians back to their initial lines, providing an unlikely outcome to one of the greatest tank battles of history.

The war was not yet over – the Israeli forces were exceedingly vulnerable. Teams worked furiously to patch up damaged vehicles and get them back into action. Columns of supplies and ammunition had to be driven to the frontline units. Men had to be deployed into the threatened points. Within just two days, the Israelis were not just ready to defend against any further Syrian thrusts, but they were prepared to take the war to the enemy. General Ben-Gal, the overall commander, addressed his officers prior to the counter-offensive. Many were tired and struggling to stay awake, but his speech was particularly moving and uplifting. The men were inspired for one last effort. Two wings were organized and, crossing the international frontier, the Israelis drove into depleted Syrian formations (supported by their Moroccan and Iraqi allies).

The Israelis, including the refitted and reinforced 188th Brigade, managed to burst through the Syrian minefields and defeat the armour and anti-tank crews waiting for them. The 7th Brigade engaged in similarly bitter fighting, and, after a six-hour battle, took key road junctions and villages at strategic points. Colonel Yossi was also back in action. He had to attack the hill feature known as Tel Shams on three occasions, but each time was forced back by the Sagger anti-tank missiles that hurtled towards his vehicles. Large boulders made it difficult to manoeuvre, and an attempt by Israeli infantry to cross the open ground also failed. After further reconnaissance, Yossi found a hidden route through the boulder fields, and led eight tanks to the rear of the summit where he engaged the Syrians with a surprise attack. Anti-tank missiles smashed into each of his vehicles, and Yossi himself was thrown from the turret of the lead tank. At nightfall, this wounded officer was rescued by a paratroop unit that stormed the hill. They succeeded in capturing this key position having lost only four men wounded.

The Israelis continued to press on with their advance towards Damascus, and the Syrians were forced to pull every available unit into the area. The Syrians, desperate to save their capital, massed huge concentrations of artillery and equipped infantry with anti-tank weapons, ordering them to take up positions ahead of the main defence lines under cover of darkness. President Assad called the Egyptians and pleaded with them to intensify their offensive in the Sinai to save Syria. It was a fateful request. As the Egyptians advanced beyond their anti-aircraft missile screen, deeper into the Sinai, the Israelis had the opportunity to use their skill in combined arms operations to defeat the Egyptian offensive. So successful was their counter-attack that, within days, the Israelis had managed to reach the Suez Canal and cross it, threatening the rear of the leading Egyptian divisions.

The Israelis managed to wrest back all of their lost ground on the Golan Heights and recaptured Mount Hermon on 22 October. That evening, Syria accepted a ceasefire proposed by the United Nations. They had lost 1,150 tanks, and their Iraqi and Jordanian allies had lost a further 150. Some 3,500 Syrians had been killed and 370 taken prisoner. The Israelis had lost 250 tanks, but 150 of them had been repaired and put back into action. Almost all the tanks had been hit at some point during the fighting but were still categorized as battle-worthy. The Israelis had lost 772 men, and 2,453 were wounded (although many of the latter had managed to fight on throughout the battle). All ranks had exhibited the most extraordinary courage and determination to overcome the odds against them. The battle for the Golan Heights in 1973 therefore must surely rank among the most outstanding feats of human endeavour in modern warfare.