IN 1974, I was studying to become a Roman Catholic priest. Throughout my studies, however, my anxious creative mind would oftentimes wander to all things pop culture, music, movies, art, and animation, especially during Latin class. As my mind would start to Rome, I’d turn all of the margins in the pages of my thick Latin textbooks into animated scenes à la a flip-book. While my studious classmates were focused on translating Cicero and Virgil, I was focused on animating toga-clad maidens dancing on ancient urns and Romans in chariots racing across my pages. I even animated an “aqua duck”—which consisted of a duck sliding across a stone aqueduct. (Decades later I remembered that when I was asked to come up with a name and story for a waterslide on a Disney Cruise ship.)

Latin was not my favorite subject. That’s why I added this poem, and made it appear as if it had been done with an ancient hammer and chisel in a stone-style font (as best I could with a ballpoint pen, anyway), to the inside cover of my textbook:

LATIN’S A DEAD LANGUAGE THAT’S PLAIN ENOUGH TO SEE IT KILLED OFF ALL THE ROMANS AND NOW IT’S KILLING ME!

There it was, a foreshadowing of my future: art, animation, and poetry all in one Latin book. I was drawing and creatively writing when I was supposed to be mastering an ancient language. Then one day, after miserably failing a Latin test, I felt God saying he had other plans for me. (Though I don’t think it was the Latin thing as much as it was the celibacy thing. There were more dancing maidens in my margins than anything else.) Good call, God.

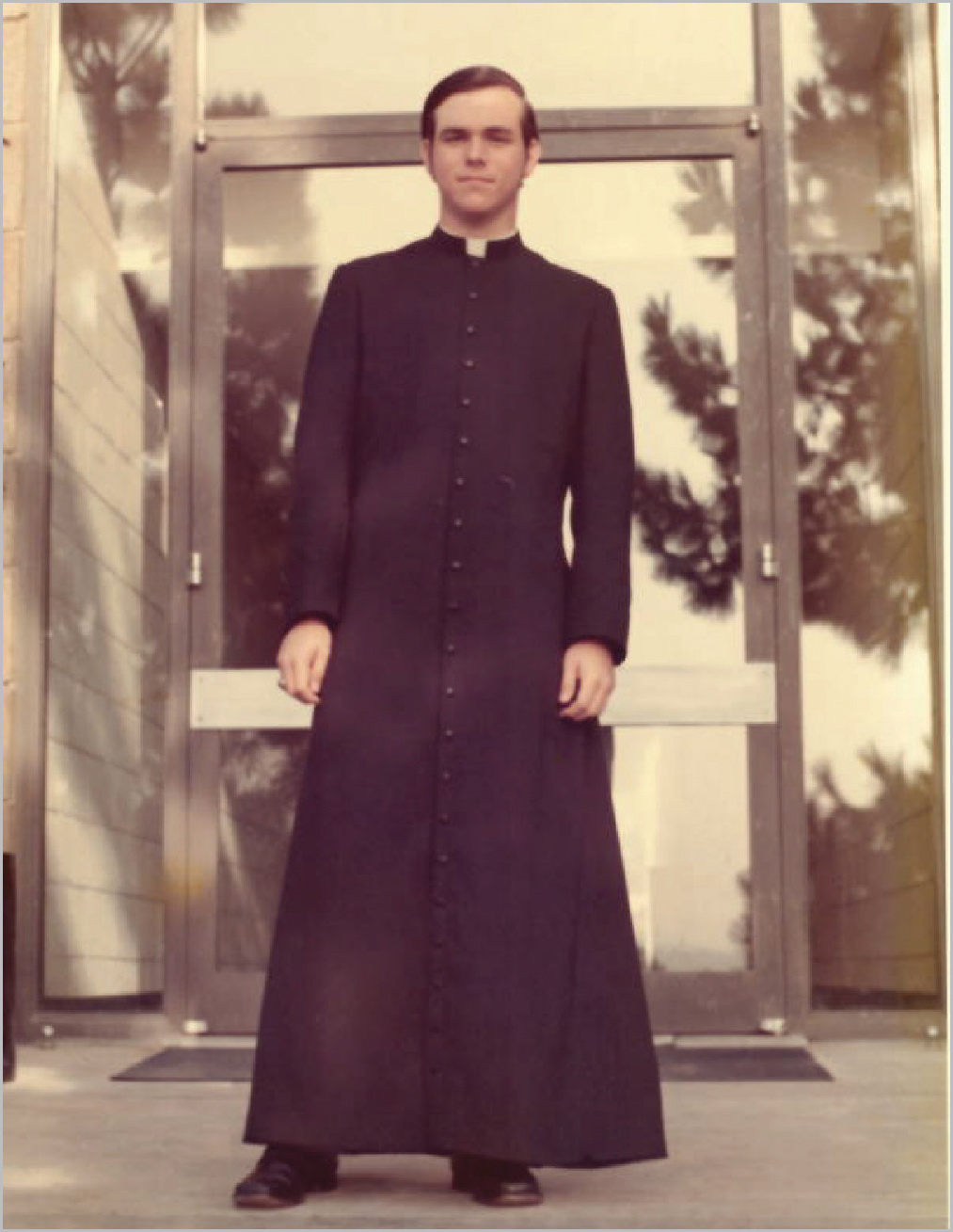

Yet I did deeply treasure my seminary experience, and it did help to calibrate my moral compass and establish a strong work ethic that would serve me well in my career. During my five formative years in the seminary, my professors were brilliant priests and nuns with high moral, disciplinary, and educational standards; and they expected nothing less from me (which is why, for the record, I did ace my Latin final. Deo gratias!). These dedicated men and women taught me well and set me up for success in the future, both in learning and in life. At the end of the school year I bid them all a fond farewell and departed St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo, California, for California State University, Fullerton, where there were girls and an art department with a new animation instructor who came from Disney. With a dream to become a Disney animator myself, I switched majors from philosophy to art. Cicero would have been cool with that. After all, it was he who wrote In virtute sunt multi ascensus: “There are many degrees in excellence.”

You would never know it, but I was wearing Mickey Mouse shorts under there. It’s okay, they were holey.

“You’re too smart for art!” exclaimed my uncle Bob, who worked for the district attorney in Los Angeles. “What you need to do,” he advised, “is get your butt into Loyola Law School [in Los Angeles].” My parents, however, were fully supportive of my artistic aspirations. “If it doesn’t work out, honey,” assured my mom, “you could always work with me in the grocery store.”

My Italian grandmother, who dropped to her knees and sobbed uncontrollably when I told her I was leaving the seminary, pulled herself together long enough to insist I go to business school so I could run my uncle Lou’s pasta factory, which for an Italian grandmother is the next best job after being a priest.

And so it began. Friends and relatives warned me, begged me, and even bribed me not to be an artist, all claiming that an art degree was worthless and it would never help me land a real job. One of my best friends even claimed that artists are weirdos. “You don’t want to be a weirdo, do you?” To prove them all wrong, I naively made it my mission to get a job in the field of art even before I earned my art degree. With that goal in mind, in May 1974, I filled out a summer job application at Disneyland.

How could it not work out perfectly? I loved Disneyland, it’s just down the street from where I live and go to college, I can draw, and a job there would be a foot in the door with Disney as a young artist (so when I did get my art degree they would simply transfer me up to the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank). Piece of cake!

“Making cakes?” I questioned my cheerful job interviewer at Disneyland, who informed me, as though she were presenting me with a rare and priceless gem, there was a position available in the bakery backstage. “But you don’t understand,” I reasoned. “The application asked what I was applying for and I stated I wanted to be an artist. I know you have artists here. You’re Disney!” My interviewer, whose name was Marsha (and I remember that because she looked exactly like Marcia Brady from The Brady Bunch), agreed. “Yes, we do have artists, but currently we have no openings in the art department,” she responded. “Well then,” I compromised, “if I can’t be an artist yet, can I operate rides?” Marsha shook her head and said once again, “I have an opening in the bakery. That’s it. In. The. Bakery.” Her frozen, twisted facial expression looked exactly like Marcia Brady’s when she and her brother Greg fought over who got to convert the attic into his or her private bedroom.

“But I’ve never baked anything,” I assured Marsha, hoping she might listen to reason and be swayed by my honesty and puppy dog eyes to dig a little deeper and find something more suited to me. Like maybe in the art department. She fired at me point-blank. “Do you want the job?” I hemmed and hawed while teetering on the fence of this most difficult decision that I didn’t know at the time would change my entire life, both personally and professionally. I let Marsha have the attic. “Great!” she exclaimed with a victorious smile. “It starts at three a.m. tomorrow.” “What?”

I was at Disneyland at 2:00 a.m. so I would not be late on my first day. Wearing my crisp white costume (“costume” is Disneyland speak for “uniform” because Disneyland employees are not considered “employees” but rather “cast members” in that they all have a role in the show. But in my case, I was going to be performing backstage, because my role had to do with baking rolls). I nervously waited near the locked bakery door located on the loading dock behind the Plaza Inn Restaurant on Main Street. The baker to whom I was supposed to report arrived at 3:00 a.m. sharp.

“Who are you?” he asked with great surprise. I introduced myself and reminded him I was the new guy reporting for work, and on time, too. Surely, he must know about me. “I didn’t know about you,” he said, unlocking the door and flipping on the lights. “Let’s go in and check the schedule.” His eyes scanned the schedule up and down and all around as he whispered, “Lafferty, Lafferty, Lafferty….” I looked down at the bakery floor whispering, “Marsha! Marsha! Marsha!”

“Aha! There you are on page three!” the baker happily reported. I breathed a sigh of relief, as I was worried there might have been a mistake. “But there’s a mistake,” he added. “You’re not supposed to be working in the bakery at all. You’re supposed to be a DMO.” “Oh, a DMO!” I said with great relief, as if I understood what a DMO was. “But you’re not starting your shift until ten a.m.,” he continued. “Come back then and report to the area supervisor three doors down.” I had seven hours to wait, which was plenty of time to try to figure out what “DMO” stood for.

Hmmm, maybe it’s “Disneyland’s Mickey Organizer.” That would be great. I could be the guy who helps keep Mickey in line and on time. Or maybe it’s “Disneyland Major Officer.” Perhaps I was going to be a security guard. How hard could that job be in the happiest place on earth? Yes sir, things were looking up! I was certain that after thinking more about it Marsha had a change of heart and reconsidered my application, finding something much more to my liking, perhaps as a nice surprise. The sun began to rise over the nearby trash dumpster as I continued to ponder all of the marvelous things a DMO could possibly be. Maybe it’s “Disneyland Magical Operator.” Whoa, maybe I’m going to be a ride operator after all! I will have to send Marsha a nice note once I get settled in to my plush new office.

Ten o’clock finally arrived, as did the area supervisor. “Who are you?” he asked. I introduced myself and reminded him I was the new DMO reporting for work, and on time, too. “Ah,” he said, “let’s check the schedule.” I was certain that once he found me on the schedule, I would be asked to go change my clothes and he would then escort me over to my new office, somewhere in the park, where I would be a DMO, whatever that was. “Yep,” he said. “There you are. New DMO.”

I couldn’t stand it anymore. I had to ask. “What exactly is a DMO?” He looked surprised that I didn’t know. “Dish machine operator,” he answered. He escorted me through the backstage corridors of the Plaza Inn to the deep dark dank dish room. It was like a steam bath but without health benefits. Or windows. Or girls. My shift was scheduled to last until 6:30 p.m. Dirty dishes, glasses, and pots and pans were piled everywhere. God was clearly punishing me for leaving the seminary.

The dish room was supposed to be manned with four DMOs, but there were only two or three DMOs working at any given time because new hires would show up, take a look at hell, and run for their lives. Two new DMOs arrived on my first day and quit on the spot. That meant I had to cover their now vacant positions and shifts. I worked overtime on my first day, departing at 11:00 p.m. When I finally walked out of the dish room in my once-crisp white costume, I looked like I had been slaughtered in a paintball tournament. The dish room serviced both the Plaza Inn and the Inn Between (the cast member cafeteria), and the action was nonstop. Busy busboys carried bins called “bus tubs” on their shoulders that were heaping with dirty dishes, food scraps, and even from time to time dirty diapers back to the dish room with such regularity that it was impossible to ever catch up. The line outside the Plaza Inn door stretched back to Main Street all day long. Once I jumped into the never slowing, ever growing mess, it felt like I was tasked to dig out the Panama Canal with a plastic spoon. It was relentless. Being a DMO was exhausting work. And the perky pretty girls in the cute green-and-white-striped dresses that served food out front wouldn’t give a DMO the time of day. We were the dregs of the earth, the slimy, pasty bottom-feeders. Latin class was like paradise compared to this.

The next morning, as I was about to leave for Dish Room Day Two while wondering why I was going back, my dad asked how I liked my new job. I told him it was awful, horrible, and grueling, and I didn’t know hell had stainless steel walls. I explained I had to see the nurse two different times for cuts caused by broken dishes and glasses, that two new guys showed up, saw what I was doing, and quit, and that I had to cover for them, and that when I finally clocked out after thirteen hours of nonstop work—on top the seven extra hours of waiting in the dark because of the bakery snafu—I smelled like a dumpster and looked like a walking Jackson Pollock painting. “Other than that,” I told Dad, “it was great.”

He smiled and said something that got me through the entire summer (and beyond): “Son, the only time you’re going to find success before work is in the dictionary.”

Before I stepped out the door, my aunt Darlene, who was visiting from Iowa, walked in and said, “Have fun ‘working’ at Disneyland. You’re so lucky!” By midsummer I had become the old man of the sea of dishes. Dozens of one-day-only DMOs came and went, but I was still there working a minimum of sixty hours a week raking in, after taxes, $60.00. Doing the math revealed I was washing about two thousand dishes for one dollar. Meanwhile, my best friend, Mark, called to excitedly tell me he got a job at Disneyland. “You did?” I asked. “Where?” You can’t make this stuff up. “The bakery!”

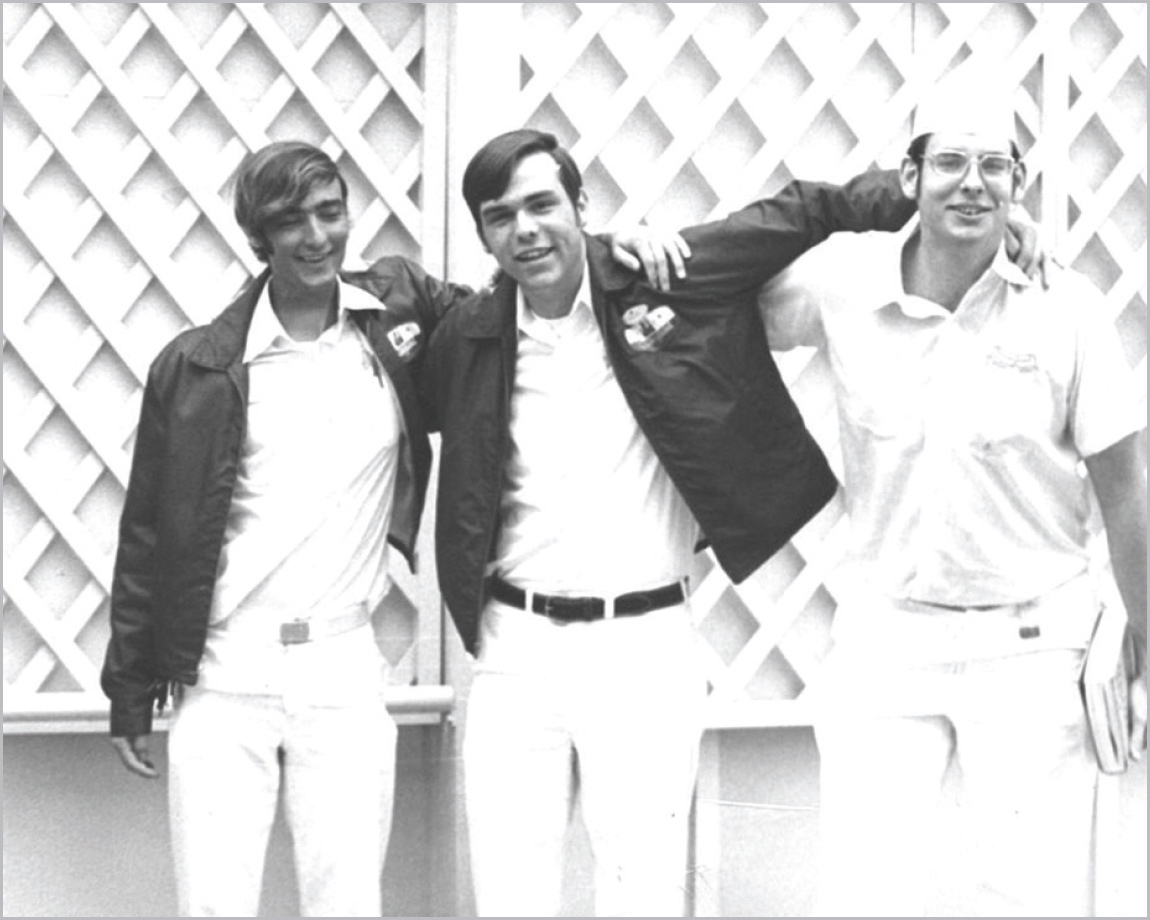

With my fellow DMOs, and obviously taken before our shift, because we are clean. There should have been four of us in the photo, but the fourth guy did not have the stamina and quit. But I covered for him. I outlasted these other two, too.

A lot happened that first summer even though I spent most of my life in the dish room being avoided like the plague by the Plaza Inn girls. I thought when I left the seminary girls would dance and swoon around me all day long like in an Elvis movie. It didn’t matter. I had no time for them anyway. Mark, on the other hand, loved working in the bakery. He was in his element, having baked cakes, pies, and cupcakes just for fun since fourth grade. Part of his job was delivering baked goods to the restaurants around the park, which gave him an opportunity to flirt with all the girls. And unlike toxic me, he smelled like whipped cream.

He was particularly sweet on a girl named Patty, who worked at the Coca-Cola Refreshment Corner on Main Street. When he delivered trays of brownies to Coke Corner in the morning, he wrote notes to her in the frosting. Smooth move. But when Patty introduced baker Mark to her best friend, Evelyn, he fell like an underbaked cake.

This is where the cosmic forces of Disneyland began to kick into high gear for me. Mark and Evelyn began dating and on Mark’s birthday, Evelyn came to his house and brought Patty along with her. This is when and where I met Patty. “Small world,” she said when she found out I worked at Disneyland, too. “What do you do there?” I crossed my fingers and hoped for the best. “I’m a…DMO.” “Oh,” she said as if she understood what a DMO was. But it was obvious she didn’t because she kept talking with me. We had a nice chat that evening but nothing came of it. The next day I ran into her in the cast member parking lot at Disneyland. I also began to see her frequently backstage, and when school started in September, I saw her at Cal State Fullerton.

We both continued to work part-time at the park—and Disneyland, in its wisdom, made sure we kept bumping into each other often, and at the most unexpected times. Patty already had a boyfriend, of course: a conservative Ken Doll dental student that her parents adored because he was one year away from having a real job, not to mention a “Dr.” in front of his name. But I liked Patty a lot. She was sweet, beautiful, and wholesome, a true poster girl for Disney. Her sister, Linda, was a dancer at the Golden Horseshoe Revue, my all-time favorite show and her brother, Steve, operated rides at Knott’s Berry Farm.

Remembering what my dad said about achieving success before work, I went to work on Patty and ultimately landed a date. When I met her parents her stone-faced, deadly serious intimidating dad asked what I did for work. “I, um,…am a DMO, sir.” “What the hell is that?” “I, uh, wash…dishes.” He grimaced and growled. And I swear this to be true: his giant terrifying German shepherd growled at the very same time.

“Are you in school?” he asked. “Yes,” I responded. “What are you majoring in?” Gulp. “Art.” He didn’t have to speak. The look in his eyes said it all: You are a loser with no future, and you are also a weirdo—and my daughter happens to be dating a dental student who is about to make bank, so get the hell out. The German shepherd showed teeth. I thought I would never see Patty again. But strangely enough we continued to run into each other in the cast member parking lot. Disneyland clearly wanted us together. It was Patty, after all, who encouraged me to apply at WED Enterprises (later renamed Walt Disney Imagineering)—but more on that later. Let’s go back to the dish room to close this chapter, because it sets the stage for what happens next.

Procedure dictated a plumber be called when the garbage disposal went kaput or the floor drains clogged and backed up. Problem was that “a plumber” was actually four plumbers who would take forever to arrive. One would assess the situation while the other three scratched their heads. They’d leave for a while and return with a new part while more than two thousand dirty dishes stacked up. For my own survival, I learned to take these matters into my own hands. I figured out that I could fix the garbage disposal in less than two minutes. When it came to clearing the clogged drains, I turned to the soda fountain. There, behind the fountain, was an array of pressurized carbon dioxide tanks. I would disconnect and “borrow” a CO2 tank and wrap a towel around the end of its connector hose to create a makeshift gasket. Then voilà! The clog would get blown away with an audible whoosh.

One day when the drains backed up, I went to fetch a tank and a towel as usual. After checking to make sure there was no supervisor in sight, I shoved the towel-wrapped end of the hose into the drain, turned the valve, and waited. And waited. I opened the valve all the way. Nothing. Then suddenly I heard the release, but this time it sounded like an underground sonic boom followed by bloodcurdling screams coming from the other side of the door—the door that opened into the onstage restaurant serving area. A Plaza Inn girl popped her head through the door, saw me kneeling over the drain hole with hose in hand, and yelled, “RUN! Run away and never come back!” I hesitated. Is she talking to me? Why would she—“NOW!” I ran like Snow White through a dense forest of mops, shelves, and food racks out the back door, jumped off the loading dock, and crouched behind a dumpster, where I hid frozen in fear for at least ten minutes.

Finally, my fellow DMO came out to find me. “You are not going to believe what you just did,” he said as if he were addressing a hero. Well, here’s what happened: the floor drains are all connected to one pipeline. When I opened the CO2 valve, the drains that decided to clear were the ones onstage in the restaurant directly behind the service area where guests stood in line and were served their food by the girls who never talked to me. It so happened, at that very moment, that standing in the fallout zone of what was to become known as “Old Faceful Geyser” were Dick Nunis, then president of Disneyland, and two of his executive entourage (Ron Dominguez and Jim Cora).

Dick was a man who instilled fear in every cast member. The trio was in line with their trays when the drain covers blew off and flipped through the air like pancakes, followed by gushing geysers of thick black muck that blasted out of the ground like a crude oil strike. The muck spattered their faces, coats, and ties. I could and probably should have been justifiably fired right then and there—and that would have been it for me at Disney. But Disneyland protected me. I was destined to be an Imagineer. For the rest of the summer of 1974, I was a Plaza Inn legend. The girls still didn’t talk to me, but they talked about me. I mucked Dick Nunis and lived to tell the tale. (Dick, if you’re reading this, IT WAS ME! Can’t fire me now! HA HA!)

As summer drew to a close—and I worked more overtime than ever—Disneyland was also working overtime to get my attention. During my breaks, I would head across Main Street, slip backstage behind the Jungle Cruise, and escape through the rubber plants into the tropical paradise of the Tahitian Terrace Restaurant in Adventureland. In a park filled to the brim with summer guests, I happened upon this tranquil eye in the storm that, between live shows, was strangely but serenely vacant. For ten glorious minutes, I had this lovely paradise all to myself, a world away from the deluge of dishes. It was there I hatched a scheme to explore more of the park after dark. At park closing, even after working a twelve-hour shift, I would clock out and then explore every inch behind the scenes, trying to figure out how everything worked and marveling at the showmanship. Sometimes the third-shift maintenance folks were kind enough to give me a personal tour explaining the Audio-Animatronics and ride systems. It was a magical time for me. But it wasn’t as magical as that one special night that brought my first summer season to an unexpected grand finale.

Overtime carried me to closing shift almost every night. The DMO closer’s job included going outside to the Plaza Inn’s patio and turning the chairs upside down on top of the tables. While performing that task late one night, for some reason I took notice of the sparkling lights in the trees on Main Street, as if seeing them for the first time. My attention turned to the tired but happy guests talking among themselves about their favorite memories of their day as they strolled past me on their way out. “That was the best day of my life,” said a petite elderly woman whose wheelchair was being pushed by a young girl who smiled and added, “Mine too, Grandma.” She was holding the string of a Mickey Mouse balloon in one hand and a giant lollipop in the other—no, not the young girl, but Grandma.

Here I am in the Disneyland cast cafeteria, the Inn Between, happy to be on the other side of the wall from the dish room!

I didn’t just see their love, I felt it. That moment could not have been staged, timed, lit, or art directed more perfectly or beautifully. Those two, separated in age by sixty or seventy years, brought it all home for me. This is why I was here. This is what Disneyland is all about. It’s a reassuring eye in the storm in a turbulent world where friends and family can spend time together and enjoy each other, where dirty dishes remain hidden and a Mickey balloon can lift the spirit of an infirm woman of eighty and make her feel like she’s eight again. That night it all became crystal clear: Disneyland was much more than a happy place or a park or even a job. It had the special power to give someone the gift of the best day of her life. I didn’t want to be an animator anymore. I wanted to be an Imagineer.