PELICAN ALLEY was one of my favorite places at WED from 1978 to 1981. It was located inside the massive MAPO building (short for MAry POppins, because it was funded by the proceeds of the successful 1964 Academy Award–winning film that featured a scene with Mary singing with another talented actor, an Audio-Animatronics bird perched upon her finger) in the backyard of the 1401 Flower Street headquarters in Glendale. Pelican Alley was affectionately named after the first family of fine feathered friends brought to life using Audio-Animatronics technology—and was home to dozens of lab-coated technicians, machinists, and tinkerers who were busy building all of the animated show props and life-sized Audio-Animatronics actors for our two groundbreaking (literally and figuratively) new parks: EPCOT Center (now known as Epcot) and Tokyo Disneyland.

Unlike the precise assembly plans created today with computer-aided design software, the folks at MAPO didn’t have much in the way of detailed drawings to guide the manufacturing of their figures. They did a lot of shoot-from-the-hip inventing and fabricating right at their workbenches. The place, which was always bustling, smelled like plastic, steel, and hydraulic oil. It was never quiet because of the cacophony of mechanical and percussive sounds emanating from drills, hammers, ratchets, part-making machinery, and the distinct “clickity-clicks” made by animated eyelids, mouths, and beaks opening and closing. These fasten-atin’ rhythms could have perfectly played along with the song “Heigh-Ho” from Snow White. Oftentimes I imagined the “Mechanical Musicians of MAPO” breaking into song like in a movie musical (imagine along…):

We tap tap tap tap drill punch drill making figures all day through

To saw saw saw saw tap drill grind is what we like to do

It feels so great to animate

Then pack it up and put it in a crate

For a ride! For a ride! For a show! For a show!

Where a billion guests will go!

Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho

We’re working in MAPO

(Whistle)

Heigh-ho, heigh-ho, heigh-ho, heigh-ho…

If ever there was a place that personified the vibrant vibe of Santa’s workshop, this was it. MAPO was established in the mid-1960s as a state-of-the-art facility in which all future Audio-Animatronics design and development could be housed in one place with plenty of space close to the WED headquarters building. By the time I happened upon the scene, MAPO already had a most interesting and successful history, because it was here that the famous actors from Disneyland and the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World, including many of the ghosts in Haunted Mansion, the pirates in Pirates of the Caribbean, the cast of America Sings, and several others, were produced.

Talk about cool! Standing in the heart of the MAPO building, I often thought about those late nights I spent sneaking through the shadows behind the scenes at Disneyland, before I even knew there was a MAPO, to study the costumes, staging, and inner workings of the Audio-Animatronics actors that began their life right here. (At the time of this writing, the MAPO building, which no longer houses animated prop and figure production, is a mysterious, top secret facility accessible only to the team of Imagineers who are working to bring the worlds of Star Wars to life in our parks. MAPO the Force be with them.)

Several months after being hired, as I started to settle in and become more comfortable with my surroundings and responsibilities, I looked forward to spending my two daily fifteen-minute breaks combing the campus in an effort to stay up to speed on what everyone from almost every discipline was dreaming and doing. Stops along my regular route were the massive main model shop, where development of the giant walk-on-able room-sized model of Epcot was well underway; the sculpture shop, where many maquettes and character busts were taking shape; the special effects department, where among many other mind-blowing things, there was “hot” glowing lava oozing out of a volcano mock-up for the Universe of Energy pavilion (thanks to the unorthodox use of an industrial dog-food pump); and of course MAPO, where there was always so much activity taking place. Amid the shelved robotic bits of history and “spares” were many birds, feathered and unfeathered, bodied and bodiless.

There were also dinosaur heads, skinned and skinless, and other recognizable and not-so-recognizable animals, figures, and related parts. The MAPO team was literally putting together the entire cast for two brand-new theme parks before my very eyes.

Inevitably, whenever I’d happen upon one of the A.A. figure technicians who was ready to try out a new function or movement, my break time would be over—and darn, I’d have to miss it. “Hey,” a technician would call out to me as I strolled by with a curious look. “Wanna see how Will Rogers is gonna twirl his rope?” “YES!!!” But then I’d glance at my watch. “NO! Gotta go, or Sheriff Don is gonna twirl his rope around my neck!” All of this dashing around to satisfy my curiosity while the break-time clock was ticking down reminded me of Supermarket Sweep, a 1960s TV game show in which contestants were given the opportunity to run through the aisles of a supermarket with a shopping cart and stuff all the groceries they could into it in sixty seconds. I only had a few minutes to run around to one or more of my favorite places to stuff all I could into my “snooping cart” before booking it back to special services not a second too late—or face the steely-eyed wrath of Sheriff Don! I never had to face his wrath, by the way. It turns out Don’s bark was worse than his bite and he had a heart as big as Texas.

Blaine Gibson, the head sculptor at WED (he was the head sculptor because he sculpted heads), was the busiest artist on earth when he started working on the busts for the actors slated to perform at Tokyo Disneyland and Epcot, including the hosts of The American Adventure (Mark Twain and Benjamin Franklin); a cast of dozens of others for World of Motion, Horizons, and Spaceship Earth; and Dreamfinder for Journey into Imagination, to name a few. (Many of his originals can still be seen today in the sculpture shop at 1401 Flower, which looks and smells exactly the same today as it did back then.) As Blaine was trying to stay ahead with the heads in our headquarters building, MAPO was building their aluminum and steel human frames, skull structures, clear plastic body panels, mechanical eyes, teeth, skin, and the crazy quagmire of quirky hydraulic actuators and related technology stuffed inside of them that would ultimately bring them to life. Truly it was glorious watching them all come together knowing full well the secret of where they would be going and what they would all be doing.

One day in 1980, while on break and making tracks over at MAPO, I ran into a highly animated figure I didn’t at all expect to see—and it was quite a wonderful surprise. Mark Rhodes, who had worked with me at Club 33, had transferred to WED as I did and was on his way to find and surprise me. I had no idea Mark was at WED, and his abrupt arrival was quite a surprise to him, too. As fate would have it, his becoming an Imagineer was meant to be and would eventually benefit both of us “creative types” even though neither one of us started in the creative division.

But hold that thought. Just as MAPO was built from the proceeds of a movie, Mark, an actor, musician, sculptor, snake oil salesman, and published novelist, used the proceeds of his two best-selling novels, written while he was in college no less, to build something tied to what he most dearly loved: movies. Unheard of at the time, especially in his hometown of Woodland Park, Colorado, Mark boldly built something called a Cineplex. But it turns out his small town was not big enough to support a Cineplex, so he lost his shirt. Flat broke, he packed a borrowed car with what little he had left, including his brother, and drove out to California to apply for a job at Disneyland because, and I’m not kidding (and he himself will validate this), he was after Walt’s old job. In fact, when he arrived at the Disneyland casting office, that’s the very three-word job description he penciled in on his application. Disneyland didn’t hire him, go figure; but they did hire his brother on the spot, who stated on his application he “would do anything.”

My old pal ex-Imagineer Mark Rhodes recently stopped by Imagineering for a visit, and we enjoyed a happy reunion. In the background is the MAPO building where he surprised me forty years prior in our early days as young and feisty Imagineers.

Mark applied a second time hoping that perhaps his charismatic charm, good looks, and acting experience would land him a job as a Jungle Cruise skipper. They did not. Taking advice from his newly hired brother, Mark’s third application declared he “would do anything.” He was hired on the spot and assigned as a busboy (“Utility Man”) at Club 33, where we met in 1976. Kindred spirits, Mark and I quickly became friends and spent a lot of time together in and outside of work. Like me he was a dreamer, creative to the core, with big plans for a future at Disney.

Since he’d written a screenplay for Paramount, albeit for a film project that got canceled, I always thought movie-buff Mark would end up at the Disney Studio writing and directing, especially after he rented an apartment in Anaheim and filled it not with furniture but with movie posters that completely covered every square inch of the walls. During my last few months at Club 33, Mark became maître d’ and then bartender, because he was over twenty-one and had tended bar in Colorado, which was a surprise to me, but it was typical of Mark to be so Walter Mitty. The man was ahead of his time and wise beyond his years and on top of all that fancied himself as the swashbuckling Errol Flynn.

And darned if he wasn’t the spitting image of Errol Flynn, sans the mustache, because he had to shave it off to work at Disneyland. No one at his tender age of twenty-three could possibly have experienced as much in life as Mark had by the time I met him, including marrying Jeannie the popcorn girl from his failed Cineplex.

A natural-born storyteller, Mark claimed everything he ever told me about himself was true, which was hard to believe. And although he doled out some doozies, even his tallest of tales always turned out to be true. An expert about all things related to cinema, he once boasted his uncle worked on the movie The Wizard of Oz, claiming if you look in just the right place at just the right time you could see him pop out of the background forest by mistake while Dorothy, the Cowardly Lion, and the Tin Man were skipping along on the Yellow Brick Road.

Of course, I didn’t believe that. Who would? And there were no VCRs at that time to freeze-frame and prove it. So, one night, when The Wizard of Oz was scheduled to be on TV, Mark invited me over to his apartment so he could prove his point by pointing out his uncle. (By the way, the first piece of furniture Mark bought for his apartment was a TV so he could watch movies.) “Ready?” he said as the moment drew near. “Okay, watch closely and don’t blink,” he said excitedly as he pressed his finger on the TV screen at the spot where his uncle was supposedly about to appear. “And…THERE! See?” But I didn’t see anything, just as I expected.

A few years later, when VCRs did come along, I did the step-through-the-frames thing on the tape of the movie looking for that blip of a moment in that scene, and by golly there was the vague shape of a man partially popping out of the trees beside the Yellow Brick Road noticing it was a hot set and popping back in!

For this and for more reasons than there is room to write in this book, Mark Rhodes was The Most Interesting Man in the World long before that bearded beer guy on TV had garnered that title. (The weird thing is, if you see Mark today, he looks exactly like that bearded beer guy.)

Having had all those unbelievable but true experiences—and the creative talent to do anything in the entertainment industry—Mark was a true Imagineer in the making; yet he didn’t even know it. But WED knew it and began to put all of its Donald Ducks in a row to make it so. When I transferred out of Club 33, I left many friends behind, including—and mostly—Mark. As noted earlier, I didn’t know anyone when I arrived at WED. I was a wayward orphan of sorts, trying to survive the best I could on its crazy streets of dreams.

During that very same week when I came to WED, and “suffered” a demotion to do it, Mark got a promotion to lead position at the Mile Long Bar in Bear Country at Disneyland. Shortly after that he became lead at the Blue Bayou Restaurant in New Orleans Square. We kept in touch, of course, but I didn’t know he would be coming up to WED because he didn’t know it either. All Imagineers have their own unique and interesting stories about how they became Imagineers, but surprisingly, when compared to the collective numbers through the decades, there have been relatively few of us Disneylanders that made the transfer from Anaheim up to glorious Glendale (the most noted and celebrated, of course, being Marty Sklar and Tony Baxter).

But here’s how Mark did it without even realizing he was doing it: while he was lead at the Blue Bayou, Tokyo Disneyland was being planned at WED. One of the requirements of the Oriental Land Company, Disney’s business partner in the bold new venture to build the first Disney theme park outside of the United States, was that every shop, restaurant, and attraction at Disneyland and at Walt Disney World provide them with a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) from which they could study and learn how Disney operated their American parks. Since SOPs did not exist for many locations, or were so old they were no longer relevant, a major task began park-wide to begin writing new ones or updating old ones to send to our Japanese partners. This task was put upon the leads of all park locations. Since Mark was the lead at the Blue Bayou, he was asked to write the SOP for that location; and since he had professional writing experience they tossed in the Mile Long Bar and Cafe Orleans as well.

After completing the three SOPs in his entertaining yet informative style, Mark was summoned to meet with Disneyland vice president Jim Cora, who had embarked on a new role to work in close liaison with the top executives of the Oriental Land Company. As Mark was climbing the stairs behind the Fire House on Main Street to Jim’s office, he naturally thought he was going to be fired (as he often thought—and sometimes rightfully so). But Jim liked Mark’s SOPs so much he asked if he would be interested in writing all of the SOPs for Disneyland! After working on them for several months and consistently delivering the quality goods, Mark was surprised when asked if he would consider transferring to WED to head up a new department called “Scope Writing,” which was established to create descriptive documents that would capture every detail about every element of the Tokyo Disneyland, EPCOT Center, and future Disneyland projects. (When I arrived, they put a duster in my hand, and when Mark arrived they put an entire department in his! Sheesh. And he got a raise! Double-sheesh!)

And here’s the clincher: Mark didn’t even know what Epcot or WED Enterprises was, but when told he’d make more money there than as lead at the Blue Bayou, he jumped at the chance to become an Imagineer, whatever that was. (As a sidenote, writing SOPs for the new attractions, shows, and shops at Tokyo Disneyland is how my dear longtime friend and colleague, ex-Disneyland sweeper and current Imagineering show writer Dave Fisher, got his broom in the door at WED.)

The week-old Scope Writing department, which was composed entirely of Mark, one electric typewriter, and a stack of blank paper, was part of the Project Estimating department under the project management division. Not the creative division, mind you. “Project Scopes” as they became known were matter-of-factly written descriptions of every element of every new theme park project in the hopper. They also included all of the pertinent facts and figures, such as facility square footages, animated figure details (including number of functions), lineal feet of ride track, ride vehicle specs, audio and lighting equipment, etc.; the list goes on and on.

These handy all-encompassing encyclopedias, which became the “go to” source for all project information, were attached to the cost estimates for everything being designed and developed, including shops, restaurants, back-of-house facilities, shows, attractions, entire lands, and entire parks. In a nutshell, the scopes, which evolved concurrent to the evolution of the projects themselves, helped explain and therefore justify the numbers in the estimates. Since there were so many projects going on in different phases of development, keeping up with the sheer number of scopes ended up being a big daunting deal for Mark, especially since changes were being made every day; and each and every one had to be captured to ensure the scopes were relevant and useful. Within the project management division, there were plenty of estimators, project managers, and coordinators to cover all of the bases. But there was only one scope writer. Mark needed help.

Don Tomlin gave me my foot-in-the-door first break, but I will forever be indebted to Mark Rhodes for giving me my second break, which led to my big third break, which ultimately led to my even bigger fourth break. That’s the one that helped launch and establish my professional career at WED. Mark approached me with his plan to expand “Scope Productions,” as he renamed the department because the word productions sounded more movie-like, as in Walt Disney Productions, by bringing me in as a “graphics specialist” (not an “artist” because, after all, it was on the project management side of the fence). My job would be to embellish the scopes with the latest facility plans, elevations and ride layouts, related concept art, and progress photos. “Basically, Kev,” as Mark put it, “to make them pretty!”

At the same time, to complement our two right brains, he would bring in left-brained Bob Stephens, another pal from the park, who would gather all of the numbers, facts, and figures from the project teams. My handling of the plans and graphics, and Bob’s handling of the data, would free Mark up for the markups! He completed his department expansion plan by bringing in an eccentric, hyperactive hooligan named E. J.—who looked exactly like Elton John but behaved like Kramer from Seinfeld—to support the department with general administrative assistant duties, comedy, and the never-ending binding and distribution of the latest scopes.

There was no fancy-schmancy publication software then because there were no desktop computers. The ongoing production of scopes was accomplished with a typewriter, copy machine, and tons of three-ring binders. I did the graphics old school—by hand on the master documents. Granted, transferring into the scope department wasn’t the best use of my artistic talent, but at least it was a step up because it came with a fifty-cent-per-hour raise, plus my own phone and drawing table! (I have had that same phone number for almost forty years.)

Our little department had a big task at hand and we needed a lot of room to roll out plans and assemble all of the scopes. We set up shop in a temporary trailer parked adjacent to the cafeteria patio (known today as the Big D), not far from the trailer where I had my WED interview. As you can imagine, trying to keep up with scope production during the busiest and most expansive time at WED took a lot more time than forty hours a week. It was stressful because we all had obsessive-compulsive tendencies and would let nothing slip through the cracks.

To let off some of that pressure, we often played practical jokes on each other, especially on E. J. because, well, he deserved it. Here’s one of my all-time faves: since we didn’t have voice mail, pagers, or cell phones, the company issued little PLEASE CALL notepads. If you were away from your desk, and someone answered your phone for you, they’d write the name and number of the person who called on your pad. One day, I left a note on E. J.’s pad that read PLEASE CALL MR. LYON, with a phone number. E. J.’s pad had never been used because no one had ever called him. When he burst into our trailer Kramer-style and spotted the note he struck a pose of excited shock. E. J. then exclaimed, as if we didn’t know it, “Hey! Somebody called me!”

He looked closely at the note. “Mr. Lyon? I don’t know any Mr. Lyon,” he said. “What did he want, this Mr. Lyon?” I was straining so hard not to explode with an atomic bomb–force guffaw that tears spurted out of my eyes the way streams of water do in leapfrog fountains.

I noticed E. J. watching me mopping away the flood of tears, and I played it for all it was worth. “I don’t know, E. J. But it sounded urgent, really urgent.” To that Mark added, “Gee, Eej, hope everything’s all right. Maybe you should call right now.”

E. J. scooped up the phone. “I…I’d better call right now!” Here’s how the call went down:

VOICE ON PHONE: “Los Angeles Zoo. May I help you?

E. J.: “Yes! I’d like to speak to Mr. Lyon. It’s urgent!”

VOICE ON PHONE: “Well, Mr. Lion is napping.

Would you like to speak to Mr. Giraffe?”

While on the subject of phones, WED had an in-house intercom paging system. You could hear every page from any place you were in the building. There were so many Imagineers on the loose away from their offices or workstations you’d hear someone’s name being paged every couple of minutes. It sounded something like this: “John Hench, please dial station six. John Hench, station six.” In every hallway, there was a wall phone for answering such a page. You would push whatever number was announced after your name and then be directly connected to whoever was trying to reach you. The telephone operator, Sandy, would announce company-wide any name you would ask her to page without question. And I mean any name! We heard them all, from “Seymour Butts” to “Ebb Cott” to “Cindy Rella” to countless others.

A big hit song in 1979 was “My Sharona” by the Knack. One of our Epcot project coordinators was named Les Skalota. Every time we heard Sandy’s gravelly Roz-like voice announce, “Les Skalota, please dial station five,” every Imagineer everywhere would break into this rousing vocal rendition to the tune of “My Sharona”: “Bum bada bum ba Les Skalota.” Really, whenever that happened we were all like Pavlov’s dogs, instantly singing the Les Skalota song at the sound of his page. It happened so frequently for such a long time that we just did it without giving it a thought. Here’s proof: I was standing at the urinal in the men’s room one day next to author Ray Bradbury when there was a page for Les. I have no idea who it was, but the guy in the nearby stall sang the Les Skalota song with me. At the end of our impeccable performance, “stall man” brought it home with a perfectly timed toot. Afterward I heard the renowned author whisper to himself, “Remarkable.”

While on the subject of phones, we all had plain-Jane desk phones like the kind you had in your house in the 1960s. If you wanted to put someone on hold, you’d simply tap one of the two plastic spring-loaded thingies on top of the cradle where the handset rests; to return to the call, you’d tap it once again. One day it dawned on me that you might be able to turn this “tap ’n’ hold” into a fun feature. I tried out my theory, and to my great delight discovered you could call someone, quickly tap to put them on hold as they were answering, then quickly call someone else, tap again, and the two parties would be connected with neither one of them knowing that a third party, me, had connected them! As far as the two connected parties were concerned, they each thought the other one had called because they were both receiving calls simultaneously. And boy, was it fun listening in on their confused conversations!

PHONE 1: Hi, it’s Raellen.

PHONE 2: Oh, hi, Raellen. What can I do for you?

PHONE 1: What do you mean?

PHONE 2: What do you mean what do I mean?

PHONE 1: I mean you called me. What do you want?

PHONE 2: I don’t want anything. I didn’t call you!

PHONE 1: Then why am I on the phone speaking with you if you didn’t call me?

(LONG PAUSE)

PHONE 2: You called ME!

PHONE 1: I did not call YOU! WHO IS THIS?

PHONE 2: I have to go. Les Skalota just walked in.

PHONE 1 AND PHONE 2: Bum bada bum ba Les Skalota!

No one knows this, but I used this tele-technique to randomly connect project team members who ended up making good use of the call to work out solutions to design challenges, like, “Hey, I don’t know why you called, but while you’re on the phone, how do you think we can solve that issue with the such and such….” It was surprising how many great ideas and healthy project-advancing discussions and solutions came out of those no-one-really-called phone calls. I guess you could say my high jinks helped move the design of Epcot along!

The reality, though, was there was little time for such entertaining breaks. It was our job in Scope Productions to constantly scout out the latest designs and plans and attend as many project team meetings as we could around campus. Like news reporters, we would also frequently meet with and interview the team leaders and designers responsible for the ideation and development of all concepts to get all the latest scoops for the scopes.

While at special services, I had the opportunity to chat with and learn from the artists. But in Scope Productions it was also my job to be in constant contact with everyone contributing to every project. That being the case, my fount of learning about the company and its projects went from a trickle to a flood! It was a wonderful time to be at WED because the first generation of Imagineers was starting to merge with the second generation. There was a remarkable cross-pollination going on between the seasoned masters and the enthusiastic new writers, designers, and thinkers who had a rare world of opportunity at their feet.

Generation 2 learned the ropes at the best school in town. The Gen 2 designers were brilliant, and it was fun to watch them in action. In covering the design process and progress of the Imagination! pavilion, for example, I kept in constant contact with the young designers Steve Kirk, Tony Baxter, and Tom Morris, who were working together on the Journey into Imagination attraction. Tony was leading the overall design and development, Steve was the show designer, who also designed and sculpted the little purple dragon-like Figment character, and Tom was my age, just a kid, hand-drawing the show-set packages. We in Scope Productions relied upon their regular input to keep our scope current for the overall pavilion. All three became key creative powerhouses at Walt Disney Imagineering and each later led the design and development for a future park: Tony for Disneyland Paris, Steve for Tokyo DisneySea, and Tom for Hong Kong Disneyland.

Randy Bright, already a key creative leader in the pre-Epcot days, was second in creative command to Marty Sklar and was also writing and directing The American Adventure, including the lyrics to the song “Golden Dreams,” which still gets me every time. Randy, and his producing partner, Rick Rothschild, a theatrical genius, were our scope go-to guys for that pavilion.

Now multiply those teams by the number of other pavilions and attractions for two new parks and that’s a lot of Imagineers to meet! I didn’t know any of them when I arrived at WED, but it didn’t take long before I came to know most of them. It was an incredible time of wonder, awe, appreciation, inspiration, perspiration, and growth.

Once our department really got into the groove, Mark, Bob, and I could accurately tell you anything about everything that was going on, and who was working on what. Although not even built yet, we knew the layout and content of every element of Epcot, regardless of whether it was an entire pavilion or an area restroom, right down to the number of sinks and stalls. While the park was under construction, I supported the work on the home front, so I never had the opportunity to travel to the actual site, nor was I present at the grand opening. But years later, when I finally made it to Epcot, it felt so surreal to know a place so well that I had never actually visited in person.

The first time I stepped through the main gate it felt as though I had shrunk down to scale and was placed on the Epcot model I had studied every day as it was being built from beginning to end. You could have put a blindfold on me that first visit to Epcot and I could have taken you on a grand tour of the entire park, pointing everything out in great detail. All of the Audio-Animatronics actors I had watched coming together limb by limb and eyeball by eyeball at MAPO were performing for guests exactly as I had imagined they would. “Ben Franklin,” I whispered the first time I experienced The American Adventure. “I knew you before you learned how to walk.”

Today it’s hard to believe how the Imagineering team could have pulled off such a fresh and epic-scaled park as Epcot without cell phones, laptops, computer-aided design software, e-mail, or teleconferencing. Throughout its design and development, our two most senior creative leaders, Marty Sklar and John Hench, did not have the luxury of staying connected to Imagineers using texts or e-mails. But I’m glad they didn’t, because I believe direct contact between individual Imagineers and core project teams was far more impactful, valuable, and appreciated.

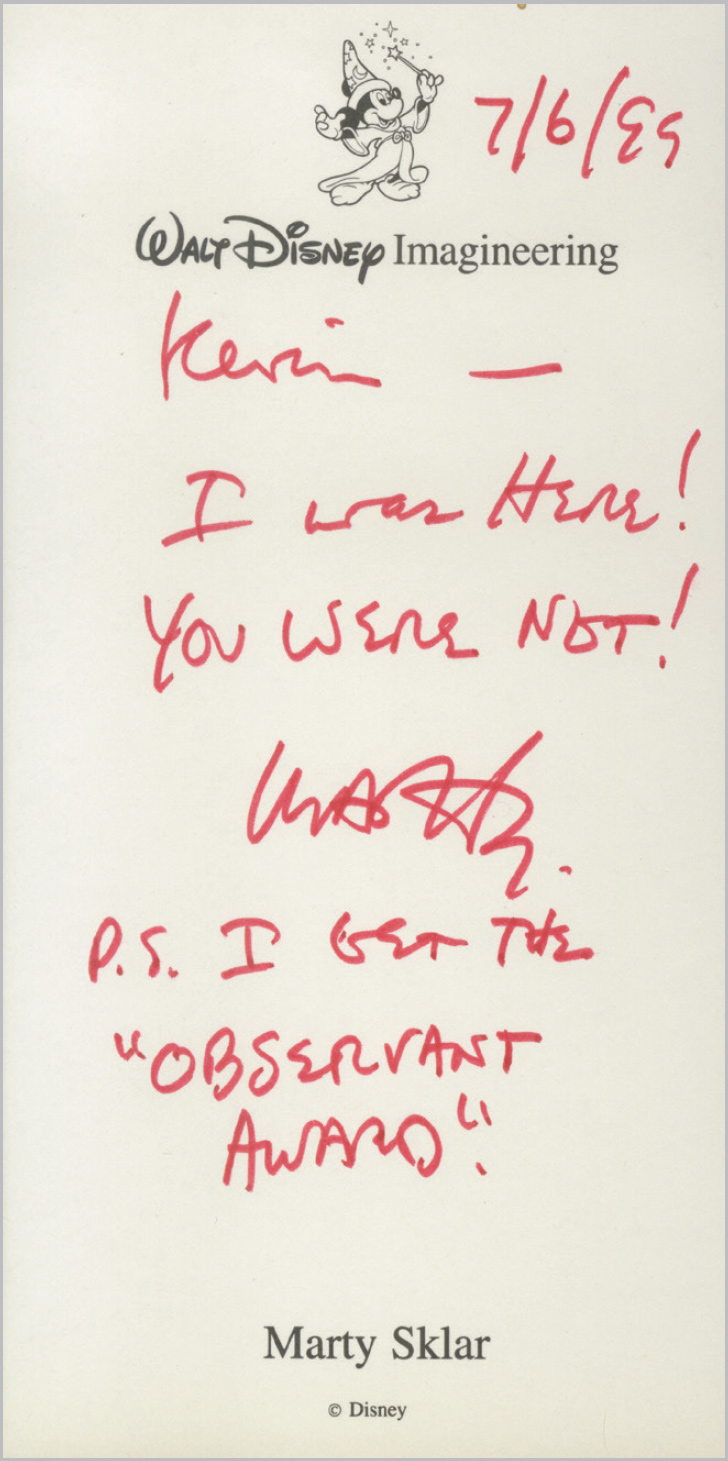

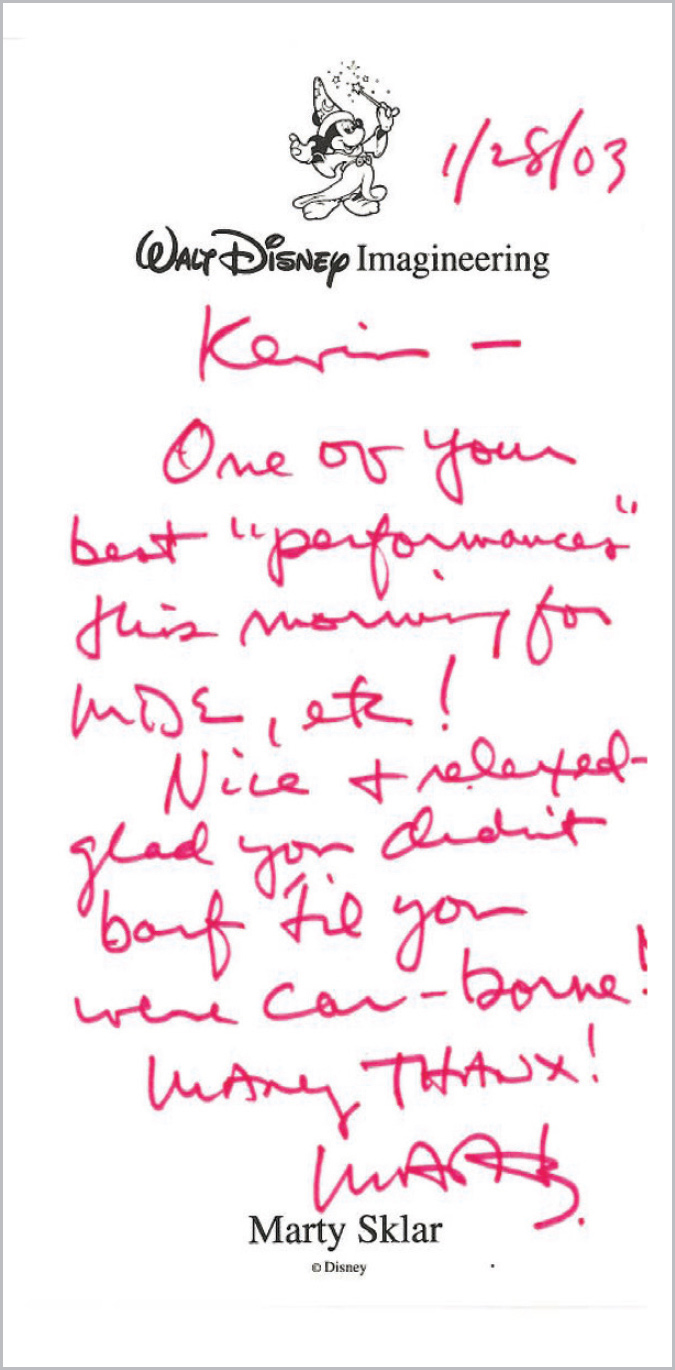

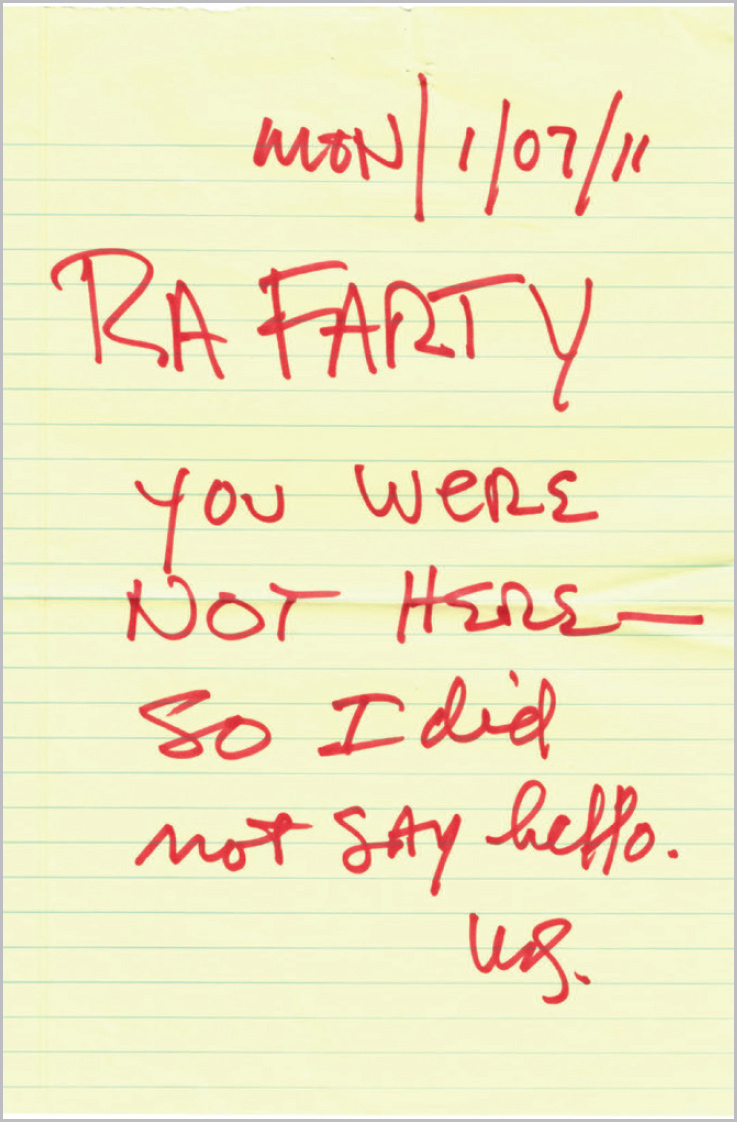

Marty and John were constantly on the move so they could check in with everyone and give direction, redirection, approval, a slap on the hand, a pat on the back, and, most importantly, their support and encouragement. You just never knew when Marty was going to pop over to see how you were doing and discuss what you were up to, business-wise and family-wise. He was passionate about his projects and his people, and as a result his people burned the midnight oil to deliver excellence—because they loved him, not because they feared him. For decades Marty was our advocate and champion, and the buck always stopped at his desk. He wrote everything by hand, red Pentel pen to paper.

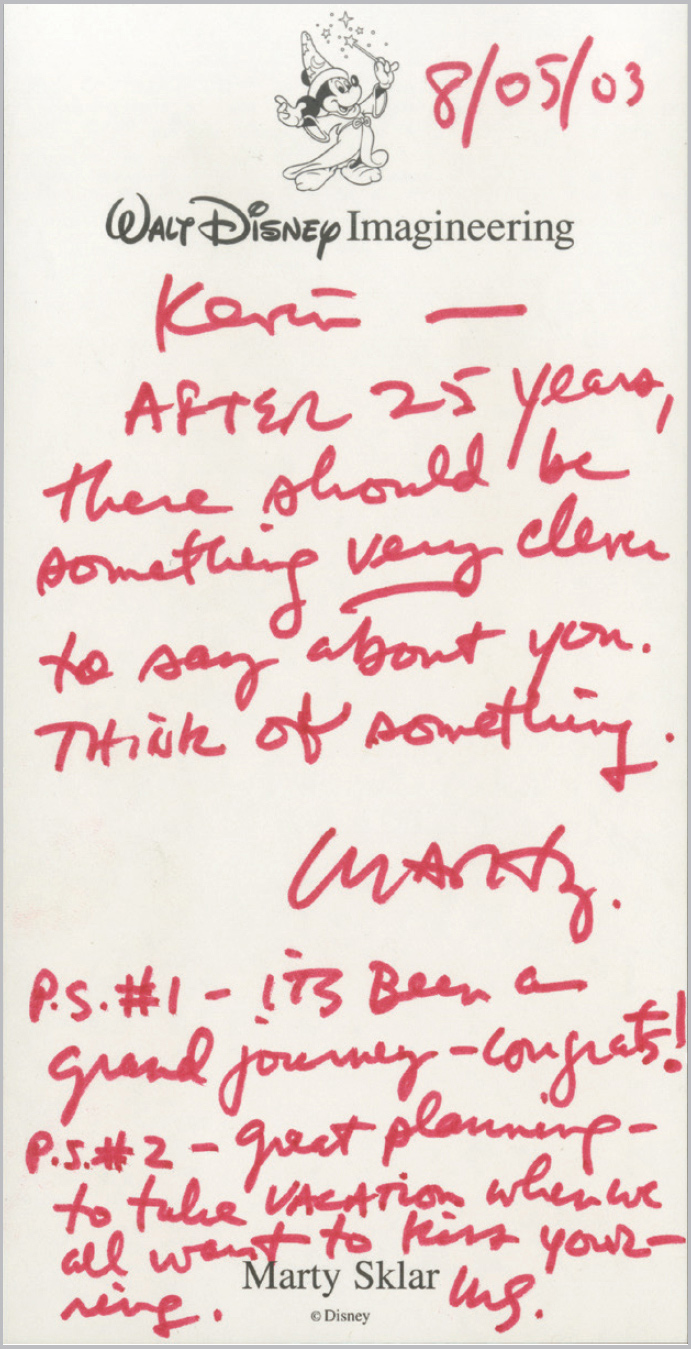

All company communication was done via hand-carried interoffice mail, but the most effective and appreciated method of communication was the personal visits and handwritten notes and sketches from Marty and John. No one knew better than Marty how to light a fire under someone’s butt that would result in their turning out more brilliant work than they had expected to put out themselves. Whenever someone went the extra mile, Marty would always send a personal note of appreciation with his famous red pen on note cards printed with his name. You’d see these red badges of courage proudly and prominently pinned to cubicle and office walls in every corner of the building; and when you’d spot one, you knew that person must have done something special. Folks would boast, “I got a Marty note today!” as if it were a winning million-dollar lottery ticket. Today I have hundreds of “Marty notes” that I consider to be among my greatest treasures. But it took many years of learning before earning my first one.

As I was a noncreative contributor during the design phases of Epcot and Tokyo Disneyland, Marty didn’t get to know me that well. But I knew him. He was a force, the force at WED, and if he wasn’t on the move in our hallowed hallways or on the road for research or at a project construction site, he was out wheeling and dealing and schmoozing with potential or existing corporate alliance partners like General Electric, General Motors, General Dynamics, and in general, many other major American companies. Whenever our general was away from WED, his support people would ask me to deliver giant piles of interoffice mail and paperwork, sometimes heaping boxes full, to his house in Anaheim, just down the street from Disneyland.

Oftentimes I’d return to my office and find a note from Marty on my chair. He was always so good about stopping by to check in on his “kids.”

Marty was always good about sending a note to me after I pitched an idea to Michael Eisner and/or Bob Iger.

I wasn’t there because I was somewhere else in the building actually working. Unlike some people.

Received on the occasion of my twenty-fifth anniversary with Imagineering. Oh, that Marty!

I lived in California’s Orange County as well, so I often dropped the stuff off at his house on my way home. I had great respect and admiration for Marty and I worried about what I would say to him if he ever appeared at his front door when I rang his doorbell. Would he even know me? I used to rehearse greetings and pleasantries should that ever occur. But it never did. I did, however, spot him sometimes in the morning barreling northbound on the Golden State freeway in his battleship gray, battleship-sized company car. That big-boat Buick would swerve, and I’d see his stacks of papers swaying back and forth on the back seat as he talked into a Dictaphone.

When I worked in special services, I’d catch a fleeting glimpse of the man on occasion, a star sighting if you will, but never spoke to him other than to offer a shy hello in passing. After all, I was the guy that emptied trash cans and set up chairs and easels in conference rooms for his meetings, not the guy that was invited to his meetings. My first actual one-on-one encounter with Marty, the first time he spoke to me directly, was when I was a new kid on the block. There I was, busy cleaning and setting up a conference room, when he unexpectedly stepped in. And he didn’t look happy. Uh-oh. I swallowed hard, hoping he wasn’t angry with me. But how could he be? I hadn’t done anything wrong. And then he pointed at my shoes and said, “You see that original art you are standing on?” I looked down and, yipes! I was standing on the edge of a painting that was poking out from under the conference room table. He continued, getting more upset with each word, “That is a Bob McCall original we are using…for…Space…ship…EARTH!” I jumped off and he stepped out. How could Marty ever let me be an artist now that he thought I had no appreciation or respect for art? I was certain he was on his way over to tell Sheriff Don to boot me out the door. Les Skalota got paged and I didn’t sing.

Thank God Marty didn’t fire me. Working in Scope Productions was the best learning and growing experience any young and inexperienced Imagineer could have had. Plus, it was great fun to be traveling along with everyone on the rocky road to reality for Epcot and Tokyo Disneyland. Our little department grew quickly, not in the number of staff but in the volume and output of work, and before long our little trailer was bustin’ at the seams. Happily, we moved across the street to the historic Grand Central Airport Terminal building where we set up shop on the entire second level. It was fun to learn that the air terminal was built the same year Mickey Mouse was born and that it boasted the first paved runway west of the Rockies, which served such notable aviators as Charles Lindbergh, Wiley Post, and Amelia Earhart.

The beautiful California Spanish colonial meets art deco–style terminal was also featured in several motion pictures. Now it was ours, and the view of the Verdugo Mountains from our spacious new digs was breathtaking. Mark and I joked about how great it was that two busboys ended up in the penthouse suite at the most unique, most secretive, most respected theme park design and development company in the world.

Life was busy but good for a couple of years. Then, before we knew it—and a zillion scopes later—Epcot and Tokyo Disneyland had been completed, opening six months apart. To celebrate, all the Imagineers gathered and jammed together in the Retlaw Enterprises parking lot behind Marty’s office and we arranged ourselves to spell out WE DID IT for a photographer on top of a ladder. But there were so many of us jammed together that we looked more like what’s packed in a can of sardines rather than legible words.

WED Enterprises had grown from only a few hundred Imagineers in the late 1970s to almost three thousand in 1983. But now our work was done. The good news was that two brand-new and beautiful Disney parks had been introduced to the world. The bad news, however, was WED Enterprises had no choice but to embark on a massive staff reduction. I was able to hang on for a few months, but the downsizing finally caught up with me. Six years after I was hired in a trailer on a cold rainy day I was laid off in the same trailer on a cold rainy day. The worst part was not being laid off. The worst part was never getting the chance to prove to Marty, the other company leaders, and to myself that I had the creative chops to transfer out of project management into the creative division. It was even more painful, thanks to my scope experience, that I had gained great and useful knowledge about the company, its people, and processes, and that I had to let it all go.

In the final act of every good story, when all is lost and the goal seems impossible, the protagonist is faced with the decision to either toss his or her sword to the ground and run away in fear or raise it up defiantly to face the fire-breathing dragon. Sure, getting laid off was devastating, especially for a young newlywed with a car payment and a new mortgage. But ceasing to be an Imagineer made me a better Imagineer. And I didn’t even have to raise a sword. It turns out the pen was mightier. It took me in the write direction.