IT’S NOT SURPRISING how many professionals in business and industry today admit their careers ended up being different from what they originally set out to do. This is especially true at Imagineering. Many Imagineers are enjoying careers they never imagined they would have, and some never imagined they’d be at Imagineering at all. Executive Vice President Kathy Mangum, for example, went to my alma mater, California State University, Fullerton, and majored in English. Kathy also started out at Disneyland, where she wore a snazzy tropical muumuu while working at an outdoor merchandise cart in Adventureland. She now leads the Atlantic Region and is responsible for all new development for Walt Disney World, and the Disney Cruise Line ships.

That’s quite a leap for someone who stood at the exit of the Jungle Cruise and sold rubber snakes and shrunken heads. Although her role today is not what you’d expect a muumuu-wearing, shrunken-head-hawking English major to be doing, I will say that her spelling, punctuation, and writing are always spot-on. (I had to ask her how to spell muumuu).

I use Kathy as an example not only because of her phenomenal success story but because we’ve worked together on so many major Imagineering projects through the decades that we’ve become family. Her first park project as producer was also my first attraction-based project as a newly minted show writer (more on that later). “Now, wait just a minute,” you say. “How did you go from getting tossed out in the cold after having your umbilical cord cut from WED to coming back to the warm embrace of the mother ship to become a show writer?” It wasn’t easy. I think Mama pushed me out of the nest so I would either start flying or hit the ground trying.

Sometimes when you reach the age that you begin to worry about your future, you so concern yourself with trying to figure out what you are going to do for a living it suppresses that skill, talent, or passion hiding deep inside of you that can tell you not what you could be doing but what you should be doing. Kathy certainly could have been an accomplished English professor or a successful anything else related to English for that matter. But I’m glad she ended up doing what she’s doing because she is a powerhouse producer with a brilliant talent for leading brilliant talent. She was meant to be an Imagineer—more specifically, an Imagineering leader.

Today English is to Kathy as art is to me (in the sense that we both still apply what we learned in college—though you could never guess what our majors were based on our job titles or professional passions). As an art major, I intended to make a living in the visual arts. I thought you had to be able to put pencil to paper and draw to be an animator. From the practical visual perspective of animation that is true. But from the emotional perspective, which is the very heart of animation, it is not.

It’s better to draw crude stick figures that help communicate a compelling and logical story than draw amazing art that does not. (I intercepted Marty Sklar in the hallway one morning and pulled him into my office to pitch the story sequence for Finding Nemo Submarine Voyage with “fish stick” figures I crudely drew on three-by-five-inch index cards.) Animation was my career goal because I wanted to touch people, to make them laugh, to make them cry, to make them feel. This does include drawings, of course, both character and background. But the emotional part of animation comes more from the heart than the art, and the heart of that art is story.

What I didn’t know then is that I should have been aspiring to be an animation story guy, not an animation artist guy. It wasn’t until after my layoff from WED that my natural knack and love for storytelling awakened, perhaps at the proper time, to tell me what I should be doing. Yep, I was always the distracted kid that drew on the walls of the house and in the margins of textbooks. But looking back on those years, it dawned on me that those were not simply drawings of things. Everything I drew served to tell a quick little story. The dancing lady on the Grecian urn in my high school Latin book turned flip-book ended her brief act by whipping around to reveal this advertisement on the back of her toga: EAT AT ZORBA’S.

In college my animation professor, Carm Goode, told me he really liked my story ideas, but I needed to work on developing my drawing skills. He recommended I take all of the life-drawing classes I could even if it meant sitting in on extra classes I wasn’t enrolled in. I dismissed what he said about my story ideas because all I heard was my art was not good enough.

When you’re aspiring to be a visual artist, that kind of comment, especially from a onetime Disney animator, raises a big ol’ red-flapping warning flag that commands immediate attention. In a panic, I reacted by zeroing in on that which wasn’t working rather than regrouping and refocusing on that which was. I went to so many life-drawing classes that I’ll bet I saw more naked people than earth would have ended up with had Adam and Eve just left that apple and those fig leaves on the tree (though the muumuu then would probably never have been invented). My life became all about working hard to support the art when the reality is, in animation and at Imagineering, it’s the art that supports the story.

The following sequence of events led to the “I could-a had a V8” realization that my real art, though untrained and untried, was writing. After the layoff, with some graphic art and layout experience at Disney on my résumé (it always helps to have Disney on your résumé), I hit the streets with my now expanded visual art portfolio and landed a job at a correspondence school headquartered in sunny Newport Beach, California. Similar to the work I did in Scope Productions, my job was to design layouts for printed materials, in this case lessons written by a staff of instructors.

The good news was I didn’t have to commute to Glendale, California. But the bad news was it wasn’t Disney. It felt different and because of that my attitude was indifferent. My heart just wasn’t in it while I was preparing all of the master material to hit the presses in the in-house printshop, including proofing all of the work. Sure, there was value to the work, as it was contributing to the education of learn-at-home students, but I used to contribute to the enjoyment of Disney park guests, which to me was more of an honor and privilege and a heck of a lot more fun. Things started looking up, however, when in addition to the print design and production I was given the opportunity to work under an art director to create nifty new advertising brochures and magazine ads for the school.

The small company had a small budget, so instead of hiring models for their ads and brochures they dressed me up, along with some of the women from the office, to portray happy correspondence school graduates that, thanks to the training received, now had exciting, high-paying jobs as business professionals and electricians. (I still have a pile of Popular Mechanics magazines from that time in which I’m dressed as a plaid-shirted, hard-hatted, conduit-carrying, widely smiling and big-moneymaking electrician. Shocking, I know.) In addition to modeling for the photos and designing the layouts, I also started writing some of the copy for the correspondence school ads that included such attention-grabbing all-cap gems as LEARN AT HOME AND EARN BIG MONEY!

I became obsessed with the ad biz, which shed a lot of light on my lifelong love for TV commercials and clever print and media product slogans; and I wanted to learn everything about the industry. When I started diving into all of the advertising trade magazines, I found in one of them a help wanted ad for a junior-level layout artist at a small agency in Orange County. The agency handled local accounts, including food markets, mom-and-pop restaurants, and a time-share resort company. Landing the job, I was able to parlay my graphic design and advertising experience, as minimal and unseasoned as it was, into designing resort brochures and creating and mechanically preparing print ads for magazines and newspapers, including final proofing and editing.

As I was designing and laying out ads, I began to get frustrated because I thought the copywriting and ideas for the ads themselves were, well, kinda lame. I’d wince when listening to local radio ads from our little agency because the ultrashort dialogue between characters was not clever or compelling and the jingles were a jumble. I often said to myself, Boy, if they just said this instead of that, or Man, why did they rhyme that with that? This was coming from a kid who grew up in the late 1950s and through the 1960s, when brilliant advertising became an influential force in our culture and people would use slogans in their everyday speech like “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing” and “Nothin’ says lovin’ like something from the oven.” The lack of quality and cleverness being delivered by the little ad agency I was working for made me ask the following question: “Where’s the beef?”

One day I couldn’t stand it anymore and cornered the creative director, asking if I could take a stab at copywriting for print and radio. Naturally he asked, “Do you have any writing experience?” Considering I had a little but not enough, I honestly responded, “Yes and…no.” He continued, “Maybe you should just stick to layout.” To pry open that slammed door and better advertise myself, I continued by listing my favorite TV commercials and what I loved about them.

And then to try to seal the deal, I sang a medley of my favorite catchy jingles, bringing it all home with “New Ajax laundry detergent is stronger than dirt,” because its hard-hitting BA BA BA BUM downbeat ending served as the perfect finale. As I stood there in my ta-da pose—and he stood there in his “go away, kid, you bother me” crossed-arms shaking-head pose—I knew I had to keep selling myself to get him to budge.

“As you know, good ads can touch your heart or funny bone, or both,” I continued. “A Hallmark card commercial can make you laugh and cry in thirty seconds.” Maybe it was just to shut me up, but he caved and said, “Okay, okay, you can give it a try.” To that I happily sang, “Plop-plop, fizz-fizz, oh, what a relief it is!” He told me not to push my luck.

Copywriting for advertising was great fun, and I really had a knack for making each and every word count, as driven by the brevity of the ads that had to appear in a little box of space in a newspaper or magazine or were heard in a ten-second radio spot. Advertising, after all, is really the shortest form of entertaining storytelling there is. Before long I worked my way up to writing and directing local daytime TV spots that were shot at the KDOC Channel 56 studio a few blocks away from Disneyland. This experience was most useful in my outside-of-Disney development because attraction stories are also short stories that need to be written and directed. Some attraction stories are so short that they last a whopping ninety seconds!

Copywriting forced me to distill the story and/or message down to its purest essence. The other growth experience that came out of working in the ad biz was learning to pitch an idea for a single ad or an entire campaign. You can imagine how this was useful in my continued career as an Imagineer in boosting confidence when it came to quickly and clearly communicating ideas for shows and attractions to busy executives. As far as I’m concerned, every good pitch should begin with a solid attention-grabbing, hit-’em-over-the head and slap-’em-into-submission statement—aka the one-liner. Here’s the starting line I used that took an attraction idea all the way to the finish line: “YOU GET TO HOP IN A CAR AND RACE ACROSS ORNAMENT VALLEY LIKE LIGHTNING McQUEEN.” I mean, c’mon, who wouldn’t want to do that?

Today, when young writers and designers ask for my advice about pitching, I always tell them the trick is to reduce the enormity of their big idea into one little descriptive but powerfully compelling intro line that will grab, even shock their audience and make them want to know more. If you start a pitch way down in the weeds by saying something like, “This idea uses a twenty-wheel coaster bogey system on a track hidden under a surface that looks like a road,” it’ll get choked out before it has a chance to grow. Start by telling them what the heck it is and what you get to do, then unleash more information once you have ’em hooked on the line like a fish. For example, you pass by a newspaper stand and the headline reads UFO LANDS ON CITY HALL. “What?” you gasp in shock. “I have to know more!” So, you read the secondary line: “At 8:30 Monday morning an unidentified flying object landed on top of city hall and seven purple, two-headed beings jumped out and danced the cha-cha.”

You double-gasp, “What? What?! Then what?” Now the only way to satisfy your curiosity is to buy the paper to get the whole story. That is the art of the pitch, of which I would argue the root is in advertising. Grab ’em and hook ’em, and then you can sell ’em. And once you’ve got ’em, go ahead and do the cha-cha!

As I continued to study and learn everything I could about the ad biz, another help wanted ad in an industry magazine caught my eye. Southern California Edison was looking for a proofreader/copy editor. Although it wasn’t directly related to the advertising industry, the ad was attractive for two reasons: it was a night shift position, which meant I could try to take on two jobs for a while, and it came with health insurance and other big-company benefits the small ad agency could not offer. This was an important consideration because Patty and I were expecting our first son, Kevin Jr. Edison hired me for their corporate communications department where, for a change, it was all about words, words, nothing but words.

One evening as I was arriving at work I was surprised to see an ex-Imagineer, George Anderson, heading to his car in the employee parking lot. I had no idea George worked at Edison and I ducked behind a van to hide because I had a score to settle with him. During the Epcot project, George was a planner/scheduler and had an office next door to us in Scope Productions. He carpooled with my compadres Mark and Bob, and for months, every time their car would stop in traffic, George would whip out a spray paint can, open the car door, and mark the freeway with a spot of Day-Glo orange. Why? I can only speculate that because they commuted all the way from Rancho Cucamonga (yes, that’s a real place in California—and they really did commute all the way from there), their long drive drove George over the gorge. It was really something traveling on that freeway during non-traffic hours and seeing miles and miles of George’s Day-Glo dots.

Now, though, I’d be able to get my sweet revenge for something he had done to me in our days of practical joking back at WED. George never knew I knew he did this, but he had sent me a letter typed on official Walt Disney Productions stationery signed by a name he’d completely made up: Vic Shapiro, Vice President of Corporate Considerations. The opening line read something like “I have been considering your performance and as a result you are being strongly considered with serious consideration, but only if you improve your…”

A long list of unrealistic improvement stipulations followed, which threw me for a loop because I worked my tail off to be a model Disney employee. But it looked like the real deal because it was on real corporate letterhead and was signed with a real signature in real ink. The letter never did say what I was being considered for, but its tone freaked me out. It was as if Big Brother were watching my every move. After a few weeks of losing sleep over it, I found out crazy George was the sender because I overheard him bragging to someone about it and how dumb I was to believe it. We both got laid off before I could one-up him. But here was my chance!

Working at Edison’s corporate communications office, I had total access to official company letterhead. When George received his official typed letter I’m sure he was taken aback, especially since it was signed in real ink by a major company honcho: NICK SHAPIRO, VICE PRESIDENT OF EMPLOYEE HISTORIES. It seems Mr. Shapiro had received troublesome information about a certain orange spray paint incident and for this reason would be keeping a watchful eye on George for the duration of his employment, which would be reinstated subsequent to his full payment for damages caused to the California Highway Department in the amount of $134,025.03.

I wasn’t at Edison long before I received an unexpected message on our home answering machine from Steve Sock, manager of the estimating department at WED. When I returned Steve’s call he surprised me with the news that Mark Rhodes was transferring out of project management into show writing in the creative division. Mark, God bless him, recommended I take his place as head scope writer, so Steve called to ask if I’d consider coming in to interview for the position. I remember at that exact moment thinking had I not been laid off and remained on staff at WED doing graphics, such that they were, in the estimating department, I would not have been qualified to be considered for a writing position. But now that I had had several months of practical writing experience under my belt, I thanked Steve for considering me and told him I would be happy to come in for the interview.

That’s how I returned to the wonderful world of WED. But this time as a more experienced, more valuable, and more-appreciative-of-being-an-Imagineer Imagineer. Without that outside writing experience and Mark’s inside recommendation, I may not have ever returned to WED, which means I would have missed out on that rare opportunity to come up with ideas for shows and attractions for Disney parks all over the world. Had I declined Steve’s invitation because I was mad at Disney for laying me off—or had I opted to stay to find my way in the ad biz—there would be no Twilight Zone Tower of Terror, it’s tough to be a bug!, Toy Story Midway Mania!, Radiator Springs Racers, Luigi’s Rollickin’ Roadsters, or others.

But that almost didn’t happen anyway. When I returned to WED in 1984, it was in trouble.

During my absence, the once gushing fire hose flow of approved project work had slowed to a trickle. That was bad news for Scope Productions. The good news was it gave Mark Rhodes time to moonlight from writing scopes to writing shows, even if they were in the form of blue-sky speculative ideas. He was more than happy to lend his time and talent to new concepts being tossed around in the interim. Post Epcot and Tokyo Disneyland, there were a few new ideas being kicked around, including an interactive attraction called The Black Hole Shootout, inspired by the movie The Black Hole. (Imagineering industrial and vehicle designer George McGinnis also designed the robots for that movie.) There were a few other ideas in production at that time, including The Country Bear Vacation Hoedown, Captain EO, Star Tours, and Splash Mountain (which started out being called simply Splash, per Michael Eisner’s request to name it after the Tom Hanks and Daryl Hannah movie of the same name. But there’s more to that story: it almost became our first mermaid-themed attraction long before Ariel made a splash! Good thing we had the entire cast from America Sings waiting in the wings).

Another of the blue-sky ideas starting to grow legs was a new attraction for the Norway pavilion at Epcot called Maelstrom. Mark Rhodes was cast as the show writer for Maelstrom, working alongside an energetic young art director named Joe Rohde. This was Mark’s golden ticket out of estimating and my golden ticket back into the chocolate factory, though still not in the creative division. But I figured Mark had been able to make the chocolatey-smooth move into creative, so maybe there was hope for me someday.

I was delighted to have this opportunity to come back to WED, especially since I was in charge of an entire department, comprised of, well, me. The great news that made my return even sweeter was the company bridged the time I was away, which meant I was able to reinstate my original hire date. The not so great news about my return was that it happened at a not so great time. WED was in a state of flux both project-wise and direction-wise, and although a few of the concepts being explored were picking up steam, the company was in limbo, especially from a corporate perspective. Marty Sklar, WED’s biggest advocate, champion, and savior, really was proactively scrambling behind the scenes, dreaming, scheming, and charting the course for its future.

Meanwhile, WED was under serious scrutiny as certain new corporate board members, with a bent for big business, questioned the fact that it spent money but did not make money. Imagineers knew our work helped spin the turnstiles at the parks, but the corporate books did not reflect that because it was something that could not be quantified. We did not manufacture and sell widgets to the masses; so, to a WED outsider we appeared to be a financial burden. Feature Animation was in a slump at that time too, but the rumor on the street was that WED was going to be shut down. But thanks to Marty Sklar and Roy E. Disney, it didn’t happen. They wouldn’t let it happen. Marty did not return calls or accept meetings from corporate to buy us more time while Roy was working on bringing in the dynamic duo of Michael Eisner and Frank Wells, who came as close as anyone could in replicating the hit- and history-making chemistry of Walt and Roy O.

Already giants in the movie industry, Michael was the creative half and Frank was the business half—and they could have not come to Disney at a better time. When Michael became our CEO, Marty immediately latched onto him to show him the tremendous value of WED Enterprises as a capable creative contributor to the future of the company and to the future in general. Michael, who had a fascination for how things work and how things are made, was quick to appreciate and recognize the potential for WED to contribute to all things entertainment and industry. He could not come over often enough to “the toy box at WED” and admitted it was his favorite place to hang out in the entire company. Michael honestly believed we could do anything (as do all Imagineers) and he launched us out of limbo into the limelight.

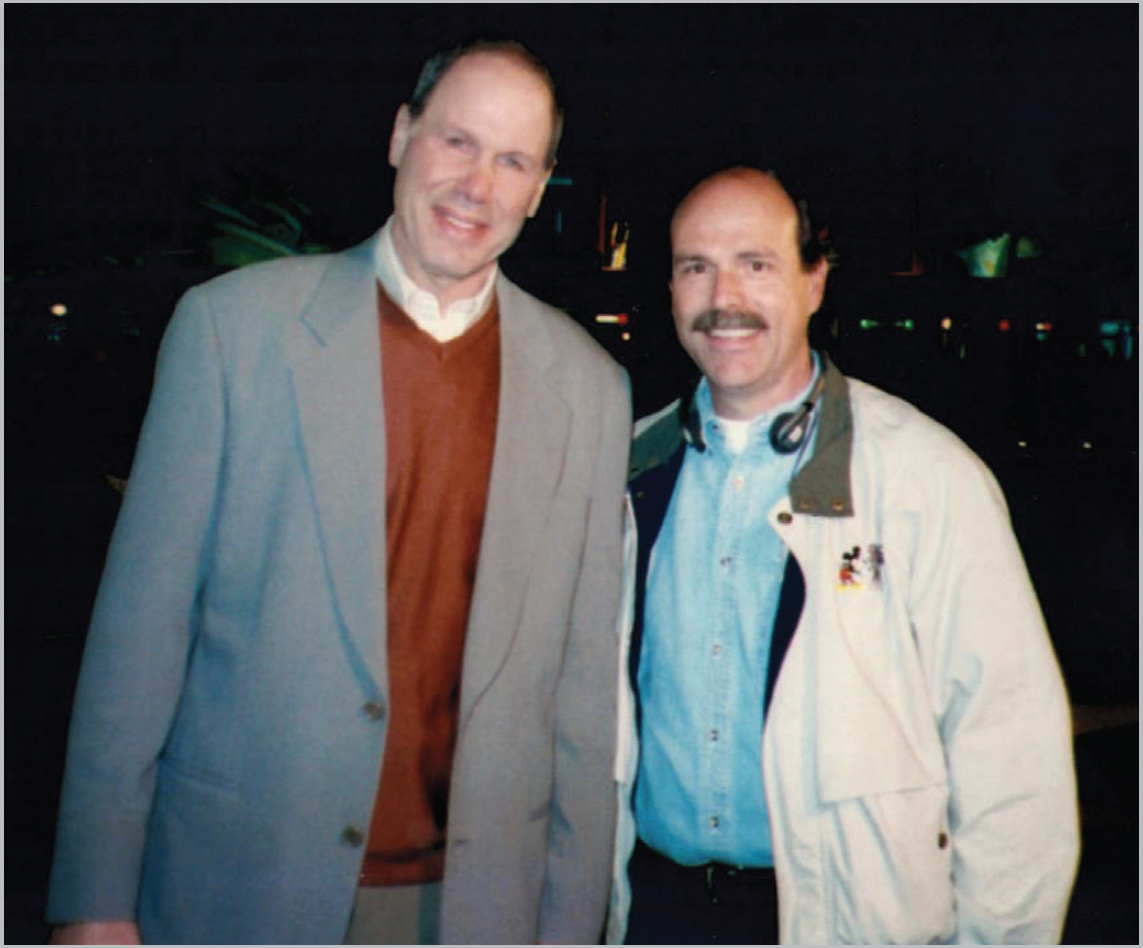

On the set with the boss, Michael Eisner. I loved pitching new ideas to this man!

One of Michael’s first requests of WED was to look at ways to design and improve many things people use in their everyday lives, including the automobile. (Alas, the Disney car was short-lived.) In 1985, Michael and Frank officially changed the name of WED Enterprises to Walt Disney Imagineering and, whoaaaa—hold on to your hats and muumuus—from that moment on it was one heck of a wild ride! With a new name, a new spirit, and a new corporate boss who ignited and challenged us to change the world, Walt Disney Imagineering soared with great purpose and passion into the future.

I feel so blessed and am so thankful to have been a creative contributor at Imagineering during that remarkable, almost unbelievable period of tremendous theme park, resort, nighttime entertainment, and cruise ship growth. For ten years, until his tragic death in 1994, Frank Wells continuously placed big bets on us as Michael relied solely on his gut to green-light one risky project after another. And guess what? That’s how you grow a company. During Michael’s twenty-one-year tenure, Imagineering launched one bold and gutsy moon shot after another.

And that’s when I got my chance to step up to the launchpad.