Chapter 4:

BEYOND THE BOX

In the book Breakpoint and Beyond: Mastering the Future Today, George Land discusses his 1968 research study of 1,600 children who were enrolled in Head Start, the government-funded preschool program for children living in poverty that I attended in 1965. In that study, the children were given the test Land had devised for NASA to help select innovative engineers and scientists, measuring their ability to look at a problem and come up with new and different innovations. The same children were retested at ten years of age and again when they were fifteen. The results were astounding: 98 percent of the youngest children fell into the “genius category of imagination,” but by the age of ten, that number was down to 30 percent; by age fifteen, 12 percent. Adults fared the worst. In 280,000 adults given the same test, a dismal 2 percent fell into the genius category. Land’s conclusion was that we are born creative and that non-creative behavior is learned. What happens to children between the ages of five and ten? Despite the inherent value of an education, some might argue it is the school system itself that inhibits creativity.

Martha Beck, the author who wanted to learn animal languages and live in the woods, was not alone in discovering school had stifled some of her creativity. My nephew Steve found that university art classes did little for his imagination, and I remember the first time my natural creativity was squelched as a child—and it wasn’t at home, where my mother snuck a Big Chief tablet into my underwear drawer to encourage my writing.

At five years of age, desperate to become a reader like my older siblings, I’d begged my sister Sharon to teach me. Instead, she read the same Dick and Jane reader aloud to me so many times I memorized it, learning to read the words by sight. To obtain the library card that was required to feed my new interest, I needed to be able to write both my first and last names. I practiced for hours until my handwriting was legible.

I skipped kindergarten altogether, beginning first grade already ahead of my peers. As a result, I was so bored, I’d pull books from the shelves near my desk and read them from my lap. When she caught me at it, the nun who was my teacher was furious I hadn’t been paying attention to her phonics lessons, accusing me of “pretending” to read the book I’d hidden. I read a few sentences aloud to demonstrate my prowess, before she snatched it from my hands in exasperation, declaring I’d learned to read “wrong.” I was confused. I’d sailed through the entire set of Dick and Jane readers and moved onto chapter books while my classmates struggled with the primer, yet I’d learned to read incorrectly?

Another milestone memory was in third grade, when I missed thirty-six consecutive school days due to illness and the teacher informed my parents I’d likely have to repeat the grade. I returned to school not only caught up with the work but once again ahead of the class. My dad had helped with the math, but I’d learned everything else from reading the textbooks that were sent home with my sister. I’m convinced those two formative experiences contributed to a disillusionment with the educational system and the foundation for a future homeschooling lifestyle.

After studying some of today’s most creative minds, neuroscientist Nancy Andreasen, one of the world’s leading experts on creativity, has pointed out that many of the people we consider to be creative geniuses dropped out of school. People such as Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg were all self-learners, or autodidacts.

“Because their thinking is different, my subjects often express the idea that standard ways of learning and teaching are not always helpful and may even be distracting, and that they prefer to learn on their own,” Andreasen wrote. They preferred figuring things out independently, “rather than being spoon-fed information.”

Learning in school has typically depended on convergent thinking patterns, where students are instructed to follow a particular set of logical steps to arrive at the correct solution—which, as we’ve seen, is not particularly conducive to creativity.

“Our entire educational system is built on convergent thinking,” Erwin McManus writes in The Artisan Soul. “Education has been reduced to the organization and dispensing of data. We teach our children that to excel in this world you have to be able to fill in the blanks. The worldview we transfer to our children is that there is always only one right answer to every problem, and that answer has already been discovered by your teachers.”

Divergent thinking, on the other hand, focuses on spontaneous, free-flowing release of creativity and imagination to explore unknown paths and discover unexpected solutions.

Because I’ve covered school board meetings as a newspaper reporter, I’ve seen how school systems today struggle to address this dichotomy, offering STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) classes and opportunities for creative growth. I’ve also seen excellent and inspiring teachers fight the system to build innovative classrooms. But in 1991, when I observed my sensitive third child’s personality change dramatically after he began junior kindergarten, I couldn’t see many options. It was my mother who initially suggested homeschooling, but I resisted. At least until the parent–teacher conference when his teacher reassured me he was adjusting and had begun “kicking and screaming like the other little boys on the playground.” That explained why gentle Michael had begun hitting his little sister at home. I promptly removed him from pre-kindergarten and his sunny disposition returned within days. That doesn’t mean it was an easy decision. At best, I began as a reluctant homeschooler.

I made the radical move with a great deal of trepidation, worrying I might be performing some sort of grand social experiment with my family by pulling away from the formal educational system that had netted me a high school diploma and college degree. The negative peer group interaction that was breaking the spirit of my third child may have prompted the choice, but, truthfully, something about the practice had always intrigued me. I’d written a research paper on home education in college. The year before I joined their ranks, I’d interviewed several homeschooling parents for the local newspaper. Certain then that I could never do the same, I was still fascinated by the difference I saw in their teenagers, who hung out with their families, played with younger siblings, and seemed relatively unaffected by the peer pressure that had plagued me as a teen.

When I made the decision to remove my children from school, I read everything I could get my hands on regarding the various techniques of homeschooling, becoming increasingly enamored with the more “relaxed” methods. I worked with our certified teacher to combine real-life experiences, copious amounts of free time, and interesting books into a relaxed curriculum that included very few textbooks. By the time we had seven children, we’d moved to a house in the country, where my children spent hours in imaginative play.

In his teens, our homeschooled Michael would roam the woods with his dog for an afternoon, a can of beans and can opener in his backpack. He read every homesteading book he could get his hands on and completed two years of math workbooks in one summer. Rachel read voraciously, devouring books like they were chips from a Pringles can. She built a complex horse ranch on the online Ponybox game, getting so skilled with her herd she had members offering her actual cash to sell some of the imaginary horses to them.

Though our isolated lifestyle wasn’t ideal for social skills, it had its merits. My rurally raised children became creative, responsible adults. In his early twenties, Michael purchased my mother’s house, converting her workroom into his own. He now makes a living with the art he creates using the self-taught skill of glassblowing. Rachel has worked her way up in a job she’s held since shortly after graduation, purchasing her own house before the age of twenty. The younger four, raised in town with more socialization opportunities, still carry fond memories of the days their older siblings entertained them for entire afternoons with elaborate puppet shows.

This is not to suggest every child should drop out of school or be homeschooled, but rather to demonstrate concrete examples of what it is to learn outside of a formal school setting, suggesting adults can do the same thing. Immersing oneself in a topic and doing extensive research for a book, learning glassblowing from YouTube instructional videos, or reading hundreds of books for enjoyment are all avenues to an autodidactic lifestyle.

I formed the creativity group at my library so I could connect with others who were interested in lifelong learning, forming a support system of sorts for a more creative life. Still, despite my eagerness to explore creative endeavors with them, my initial foray into playing a musical instrument convinced me I probably wouldn’t become a musician anytime soon. As my fingers clumsily moved from a C to a G formation on the fret of the ukulele, a familiar feeling of embarrassment crept over me, threatening to ruin the experience. Then I looked up and met the amused eyes of another woman who was struggling just as much, and we both laughed, shaking our heads. We might not be musically inclined, but we could still have fun.

Later, when our group discussed bringing in an art instructor to guide us in a painting activity, the woman sitting next to me practically jolted out of her chair.

“What? Painting? We’re going to paint?” her voice rose in panic. “I can’t paint!”

“I haven’t touched a paintbrush for forty years,” I attempted to reassure her. Several others chimed in.

“I’ve never painted either,” one said. “But I want to try.”

“If it doesn’t look like you think it should, tell everyone it’s supposed to look like that. It can be an abstract painting,” another commented with a laugh.

Our fearful member visibly relaxed with the reassurance, and soon we were talking excitedly about what we’d paint. It wouldn’t be the typical “cork and canvas” type activity, where everyone drinks wine and paints the same picture. Instead, after an initial explanation of simple painting techniques, our instructor turned us loose, encouraging our group to paint whatever we wanted. Some came prepared with a picture they’d printed out. Others searched for an image on their phone. I’d decided on a bright, bold sunflower. When I dropped my paintbrush on the canvas, the single sunflower became two, and when that made the whole thing look off balance, I added another. My brushstrokes were hesitant at first, until I remembered what I’d read in the book I’d recommended to the group before our painting session.

“The joy is in the process. The joy is in the messy, the gorgeous, the ugly, the mistakes, the success, and the feelings of how great it is to express yourself,” Rebecca Schweiger says in Release Your Creativity. “If you make the creative choice to practice a less judgmental attitude, you immediately welcome more inner peace and joy into your painting as well as into your life canvas.”

Recalling those words, I made the conscious decision to just have fun, emboldening my strokes. Unlike my clumsy efforts with the ukulele, my fingers seemed to recognize the feel of a paintbrush. I soon discovered I preferred the more expensive paints the instructor had brought, offering a texture I desired. I added subtle notes of orange and brown to the thick strokes of bright yellow.

The completed painting looked nothing like I’d imagined, but even my untrained eye could see the possibilities, and I was eager for our group to do it again, though I’m not sure all the members shared my enthusiasm. One multitalented and particularly perfectionistic member wanted to abandon her painting altogether midway through our gathering. Others found painting as frustrating as I’d found ukulele playing to be, fearful of looking foolish.

Why are so many of us afraid to try new things? One of the biggest reasons seems to be a fear of failure.

“By leaving the ‘tried and true’ pathway of action or thought, the individual exposes herself to possible failure and ridicule. That exposure is very anxiety-provoking for many people,” Harvard psychologist Shelley Carson writes in her book Your Creative Brain. “People say ‘I’m not creative,’ but that’s just not true. Every one of us is creative. The brain is a creativity machine.”

“How will I know if writing is my talent?” my daughter Katie asked when she was seventeen.

My answer came not only from the heart of a homeschooling mother who has always taken pains to encourage her children in their natural gifts but from an experienced writer who has faced repeated rejection. Writing for publication is not for the fainthearted.

“You write, and you submit, if you think that’s what you’d like to do. But you don’t let one rejection, or even ten, stop you if you think writing might be your calling. If you’re drawn to it, then write,” I told her. “Take classes, take workshops. Try different things, and you’ll discover where your passion lies.”

When we’re seventeen, the possibilities of career choice can feel overwhelming. At seventy, if we haven’t yet accomplished whatever it is we are “called” to do, we might think it is too late. After all, any craft takes time and work to develop, perhaps as many as ten thousand hours to be perfected. In his book Outliers, Malcom Gladwell popularized the “magic number of greatness” to achieving expertise in any skill as a matter of practicing ten thousand hours. Those numbers can be just as daunting at age seventeen as they are at age seventy.

“I don’t know if I have ten thousand hours left,” a woman in her seventies lamented during one of my Beginning Writing classes. I reminded her that the hours she put into writing as a child, as a teen, and into adulthood counted. She’s not starting from scratch, and even if she were, she shouldn’t let that stop her.

We shouldn’t expect our first attempts to look like our final successes. So many of us try something new only to abandon it because it doesn’t “look right” (or, in the case of my ukulele playing, sound right). There is intrinsic value in the attempt to stretch our imagination. The pursuit of a creative endeavor has merit even if it never becomes a career. We should give ourselves permission to draw because we enjoy it, paint because we find it relaxing, or write when we feel led to, whether or not we are “good enough.” Simply allowing time for it in our life can be transformative.

“Each of us possesses a creative self. Claiming that is a transformational act. When you begin to act on your creativity, what you find inside may be more valuable than what you produce for the external world. The ultimate creative act is to express what is most authentic and individual about you,” Eileen M. Clegg writes in her book Claiming Your Creative Self.

The truth is, while I enjoyed my ukulele-playing session, I’m not that interested in playing a musical instrument. I don’t want to learn to read music, and I don’t have a deep-seated desire to be a musician. Failure is always an option when we try something new, but at least I tried. I don’t need to wonder if there was some hidden musical talent within me. There isn’t. But I’ve always wanted to be a writer, ever since childhood. From that Big Chief tablet left inside my underwear drawer to the hours I spent in the local library, I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be an author, so that’s where I’ve concentrated my ten thousand hours.

This book began as a formal book proposal, a boxed-in version of what I thought my publisher might want based on my other books with the same company. It was a perfectly acceptable proposal, stemming from an idea I’d had months after my mother’s death. The format of the chapters and manuscript would have resulted in a book that looked much like my previous five. Christopher Robbins, the publisher, held on to my proposal for several weeks in relative silence before emailing to set up a phone call.

“I think we need to be more creative about a creativity book,” he began our phone conversation. Essentially, I’d put the creativity book inside a self-contained idea box, and Christopher had taken off the lid. Suddenly, with his permission and a shared vision for a creativity book, ideas flowed seamlessly. That’s what can happen when we open up our minds.

Begin your own creativity journey by taking the lid off the box you’ve contained your ideas and dreams inside. Once you do, you might be surprised by the imaginative world you find yourself in.

IGNITE

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do I With your one wild and precious life?”—Mary Oliver

My mother made scrapbooks from brown paper sacks, pasting magazine pictures of things she’d like to make someday onto the pages. She kept another notebook filled with ideas for home decorating. A collage of what I want in my life would inevitably include overflowing bookshelves and stacks of stationery—simple things that make me happy.

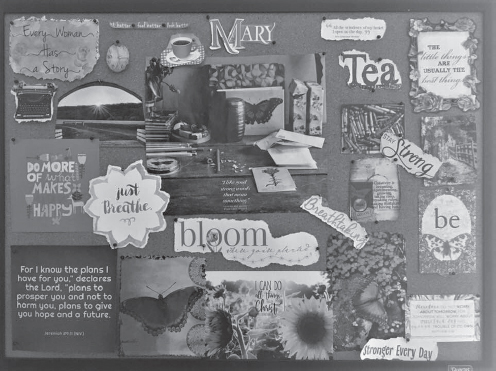

What do you envision for your life or future? What do you want to surround yourself with? What are your hopes and dreams? Look back at your mind map for ideas. Create a “vision board” alone or with a group. Tear or cut pictures and inspirational quotes and words out of magazines. You can use some of the inspirational sayings included in the back of this book. Arrange the words and pictures on poster board or pick up a bulletin board at a thrift store, like I did. The black frame looks nice on a wall where I can easily see it, and I like the idea of being able to add to or change the layout. On my first vision board, I used a Bible verse as my focal point, adding a blue butterfly that represented the husband who’d encouraged me to fly. I wanted more nature in my life and yearned to see a mountain, so those pictures were added too. A member of my lifelong learners group decided to put together a vision binder instead. Choose what works for you. What does your creative future look like?

Mary Potter Kenyon’s vision board.