Chapter 8:

GRATITUDE ADJUSTMENT

Please. Thank you. Excuse me. My parents raised their children to have good manners, and I’ve retained the habit, sometimes to the point of being excruciatingly polite. I was the woman in labor who apologized to the nurses and doctor for her cries of pain, or to cashiers when they made a mistake, as if I were the one at fault. I’ve even been known to apologize to a doorway when I bumped into it. So perhaps it was not so out of character when, two days after my husband’s death, I picked up a journal and wrote down all the things I was thankful for:

• A life insurance policy that had been reinstated just twenty-seven days before.

• The five-and-a-half years I’d cherished with David since his cancer treatment, a period when our marriage was the best it had ever been.

• Recent conversations I’d had with my husband about what he’d want me to do if he died before me, a topic we hadn’t seriously discussed before that, not even during his cancer.

• My daughter Emily having followed her compulsion in the three months previous to her dad’s death to hug him and proclaim her love repeatedly each day.

• Siblings who rushed to my side when they heard the news.

The tally went on for three pages. No one told me to do this. They wouldn’t have dared to suggest I compile a gratitude list less than forty-eight hours after a devastating loss. As a Christian, however, I’d vaguely recalled a Bible verse about “giving thanks in all things,” and as a writer, journaling seemed the appropriate method of working through my grief. While it would seem a stretch so soon after his death, coming up with that long list of things I was grateful for was surprisingly easy. I’ve turned to those pages in my journal many times in the ensuing years, whenever I need a reminder that God did indeed go before me, preparing me to lose my husband.

Continual prayer was the one form of meditation that came naturally as grief propelled me into a running conversation with God. As I carefully considered, reflected, pondered, and meditated on those things that were true, just, pure, lovely, virtuous, or praiseworthy (from Philippians 4:8), I couldn’t help but feel a semblance of gratitude.

“Gratitude is many things to many people,” Sonja Lyubomirsky wrote in The How of Happiness. “It is wondering; it is appreciation; it is looking at the bright side of a setback; it is fathoming abundance; it is thanking someone in your life; it is thanking God; it is ‘counting blessings.’ It is savoring; it is not taking things for granted; it is coping; it is present-oriented.”

According to Amy Morin in an article on PsychologyToday. com, multiple studies affirm that developing a sense of gratitude strengthens the ability to bounce back after trauma. She mentions a 2003 study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, which found that gratitude was a major contributor to an individual’s resilience following the September 11 terrorist attacks, and a 2006 study published in Behavior Research and Therapy, which suggests that Vietnam War veterans with higher levels of gratitude were less likely to experience posttraumatic stress disorder.

The study of gratitude as a science is a fairly recent phenomenon. Until the late 1990s, the topic had remained mostly within the realm of religious leaders and philosophers. That changed in October 2000, when the Templeton Foundation brought a group of thirteen scientists to Dallas, Texas, for the purpose of advancing the science of gratitude. They explored the subject from the perspectives of anthropology, biology, moral philosophy, psychology, and theology, drawing on their own research and examining the evidence that “an attitude of gratitude creates blessings.”

In his book, Thanks! How the New Science of Gratitude Can Make You Happier, Dr. Robert Emmons, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Davis, details many of those blessings, including a strengthened immune system, lowered blood pressure, higher levels of positive emotions, more joy, and increased optimism and self-esteem. Emmons, who was present at that original Temple Foundation meeting, is considered one of the foremost authorities on the topic of gratitude in North America. He looks at gratitude as “receiving and accepting all of life as a gift.”

“Without gratitude, life can be lonely, depressing and impoverished,” Emmons says. “Gratitude enriches human life. It elevates, energizes, inspires, and transforms. People are moved, opened, and humbled through expressions of gratitude.”

His definition of gratitude has two components. The first is an affirmation of goodness: affirming there are good things in the world, gifts and benefits we have received. This doesn’t mean ignoring the complaints and burdens we carry, but looking at life as a whole and identifying some amount of goodness in our life. The second part is figuring out where that goodness comes from, acknowledging that it is outside of ourselves.

For me, that is part and parcel of faith: affirming that life is a gift and that goodness comes not because of something we do but from grace. My ability to see the good in circumstances likely derives from the humbling experience of having had goodness bestowed upon me by others during David’s cancer and after his death.

Dr. Emmons views gratitude as a choice. Pete Sulack, America’s leading stress reduction expert and founder of StressRX, agrees.

“‘Negativity bias’ is our brain’s natural home base,” Sulack said in a 2016 article featured on DailyPositive.com. “It’s our go-to response in a stressful world. We tend to remember the bad while forgetting the good.

“Now we must learn a new way of seeing the world and interacting with it if we are to become resilient to the stress of living in a post-modern world,” he continues before explaining that our brain is neuroplastic, with the ability to rewire itself by practicing a habit repeatedly—in this case, the habit of gratitude.

“It is a choice to look around and take in the beauty that surrounds us instead of seeing the ugly. It’s a choice to remember the good and let go of the bad. It’s a conscious decision to find things for which to be grateful each and every day. It’s difficult, but it’s worth it.”

Choosing thankfulness under all sorts of circumstances isn’t always easy, but it’s a practice well worth cultivating for a more creative and innovative life.

“When we are stressed, we revert to behaviors that are routine, time-tested, and familiar—our ‘go to’ plan of action,” Sulack is quoted in an Inc.com article written by Kate L. Harrison. “We do this because we are in survival mode. When we are stressed, we are using an industrial, assembly-line type of thinking, instead of creative, out-of-the-box thinking.”

As we’ve touched on in previous chapters, that assembly-line mindset is counterproductive to creativity. According to Sulack, cultivating gratefulness as a habit can change that type of thinking.

“To be creative and get beyond those compensatory behaviors and try new ones, we must address the stress response,” he says. “Gratitude is one powerful way to do that. When you are grateful, your stress is reduced and you experience positive emotions. These in turn help you remember peripheral details more vividly, think outside the box, and recognize common themes among random or unassociated ideas. All of this adds up to a more creative response.”

A grateful attitude doesn’t happen overnight. We can’t just tell ourselves to look on the bright side. It’s a process we need to practice and develop as a habit, training our mind to replace negative thoughts with positive ones. One way to do that is to reflect on a time in your life when you faced adversity and then consider good things that happened because of it. My husband did this naturally after his cancer. After suffering through six months of grueling treatment, he’d often take my hand in his and remark, “If it took cancer to get this kind of relationship, then I’m glad for the cancer.”

I can look back and see how losing three important people in my life in the space of three years changed me in positive ways. I’m more empathetic, open, and eager to help others. I became a certified grief counselor and founded an annual grief retreat because of my loss, not in spite of it. I have intimately seen how God can bring good from bad.

“When times are tough, you can always be grateful for the push adversity gives you to learn and grow,” Sulack explains. “While it is easy to take the path of least resistance, griping and complaining about your situation, true leaders know that pain is part of life, but suffering is optional. Choose gratitude. Choose joy. This will make you more creative and innovative—and ultimately more successful in any endeavor.”

Blogger and author Sara Frankl did this. She knew her rare autoimmune disease was terminal, but she didn’t let that stop her from living. In the face of immeasurable pain and despite her dire circumstances, Sara made a daily decision to choose joy. Her book Choose Joy: Finding Hope and Purpose When Life Hurts, demonstrates how that conscious decision resulted in a life of beauty and faith.

“I am blessed because I take nothing for granted. I love what I have instead of yearning for what I lack. I choose to be happy, and I am. It really is that simple,” she wrote shortly before her death at age thirty-eight.

Gratitude isn’t just for the good times. It can help us through the bad ones. The word derives from the Latin gratia, meaning grace or graciousness. Through grace, I can look back at a husband’s bout with cancer and be grateful for a renewed marriage relationship that lasted another five-and-a-half years. Grace can mean falling to your knees at the side of the bed after experiencing the death of a loved one to thank God for bringing them into your life in the first place—the father who died when I was pregnant with my third child, the mother I had for an additional twenty-five years, the husband who unexpectedly died the day before his sixty-first birthday, and the eight-year-old grandson who went Home shortly after. It means filling three journal pages with thankfulness forty-eight hours after the death of a husband.

“You have to decide you want to be joyful,” Thomas Kinkade writes in Lightposts for Living. “You have to trust that life, despite its ups and downs, is essentially wonderful, that the finished tapestry of your days will be a thing of beauty.”

In pursuing our passions, following our hearts, and believing that life, and the people in the world, are mostly good, choosing gratitude and joy becomes second nature to us.

“If we are involved in doing what we were put on Earth to do, a joyful heart is almost guaranteed—even in the midst of deepest difficulties,” Kinkade continues. “Consistent and durable joy is generated when we pursue a passion that is strong enough to carry us past pain, something so meaningful and absorbing that we can ignore unhappy circumstances.”

Kinkade suggests another way of cultivating gratitude is through developing a servant’s heart in acts of everyday service to others.

“You’ll begin to realize the rewards that come from blessing others—the smile of appreciation from people at work, the thanks from the homeless person, the joy and enthusiasm of your children, the sigh of pleasure from your spouse as you rub his or her neck.”

I can pinpoint when a real shift occurred in my relationship with David. Bogged down with bills and babies, by 2004 I’d lost sight of our marriage, to the point that during our twenty-fifth wedding anniversary party, I wondered if ours was even a marriage to be celebrated. But two years later, when David was diagnosed with a cancer that had a 50 percent survival rate, I was shocked into awareness of how much he meant to me. Faced with the prospect of losing him, I made the conscious decision to put my husband first, before house and children.

One day, after a long morning of radiation and chemotherapy, David collapsed on the couch in exhaustion. I knelt down in front of him. Gently removing his socks and shoes, I began rubbing his feet. In twenty-seven years of marriage, I’d never touched that man’s feet. I looked up, and there were tears in David’s eyes. From that pivotal moment, our relationship changed dramatically. We became true partners in a newly revitalized marriage. From back rubs to bringing cups of coffee to putting the other’s needs in front of our own, we actively searched for opportunities to serve the other. Now, when I fold my teen’s laundry or make a cup of tea for one of my daughters, I’m doing the same thing: serving with a servant’s heart.

Here’s the kicker in all of this: Not only does gratitude enhance your creative life—it enhances you. Grateful people are more apt to live a life of reaching out to others. Numerous studies corroborate this. Scientists at the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley, have studied the psychology, sociology, and neuroscience of well-being, finding that people who make gratitude a consistent part of their life are more likely to act with generosity and compassion.

It makes sense that humans are not only meant to be creative but to be generous as well. According to a report commissioned by the John Templeton Foundation, research suggests there is a propensity for generosity deep within us. In an overview of more than 350 studies published between 1971 and 2017, there seems to be ample evidence that humans are biologically wired for generosity. Prosocial behaviors that benefit others trigger our brains to produce endorphins, the feel-good hormone. Not only does it feel good, but helping people helps us.

“Giving social support—whether time, effort, or goods—is associated with better overall health in older adults and volunteering is associated with delayed mortality,” a May 2018 John Templeton Foundation white paper states. “Generosity appears to have especially strong associations with psychological health and well-being.”

In a study at the University of Zurich, researchers conducted an experiment using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to understand how acts of generosity related to happiness. Their research revealed a “warm glow” from neural changes in the brain associated with happiness after any act of generosity, even the smallest act of kindness. In other words, practicing gratitude can make someone a better person.

Look at it this way: When we think of creativity, we automatically think of “making” or “creating” something. But consider for a moment how it could be in “making something” of our lives and, through the power of kindness, creating a kinder, gentler world.

Who would have thought kindness could be so powerful? A lot of people, actually. A quick Amazon search reveals over 7,000 books on the topic. Google the phrase “random acts of kindness” or the word “kindness,” and it’s evident an entire movement on the virtue has evolved. The globally recognized World Kindness Day is celebrated every November, and the Random Acts of Kindness (RAK) Foundation has extended that concept to a Random Acts of Kindness week in February. You can find an entire website, KindnessRocks.com, devoted to leaving painted stones in unexpected places to brighten people’s days, a practice that has spread all over the world. And then there’s the World Gratitude Map, a crowdsourcing project with the mission to share gratitude.

“It is moving your mind over to this place where I think we should all be, which is to keep our eyes on all that is good, beautiful, and possible in the world,” Jacqueline Lewis, one of the project’s creators, said in a 2013 LiveScience article on the gratitude project. Lewis, a writer with an interest in human resilience, has a vested interest in the project. When her mother, Joan Zawoiski Lewis, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, all she asked was that people do good deeds in her name. Her spirits were lifted by the reports of family and friends throughout the world doing just that. Jacqueline was certain that kept her mother alive for nearly twenty months longer than expected.

“While dying, her focus on these good deeds done by others kept her alive with end-stage pancreatic cancer past all reasonable prognosis,” Jacqueline said. “The [World Gratitude Map] gives the rest of us a chance to move our eyes in the same direction, perhaps derive the same benefit.”

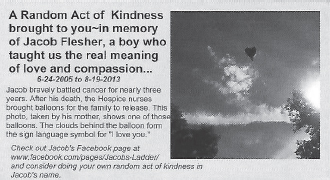

My daughter Elizabeth and I weren’t aware of any of this when we designed Random Acts of Kindness cards after my grandson Jacob died. All we knew was that his life had been much too short and we were determined his death would have meaning. He’d spent a great deal of his time in the hospital during the nearly three years he’d battled cancer. A dedicated band of Child Life Committee volunteers at the University of Iowa Hospital visited his room, bringing toys and involving him in activities designed to entertain young patients. Jacob, who sorely missed his siblings while he and his mom were in the hospital, would save the cupcakes he made with the volunteers to share with siblings back home. He’d raid his own piggy bank to purchase gifts for his big sister Becca at the hospital gift shop. And during a brief period of remission, he collected toys to take to other children in the hospital. On his deathbed, when he heard his mother complain about stiffness from sleeping on the floor next to him, his thin arm reached out from underneath the blanket to rub her back.

The best way we could honor such a precious child was to be more like him, to become better people because of him. To be kinder. We designed cards that included his name and the Jacob’s Ladder Facebook Page and began doing random acts of kindness in memory of Jacob. All over the country there were people following his cancer journey who vowed to do the same. Medical bills were paid off anonymously, groceries purchased for needy families, and acts of kindness shared on the Facebook page. Other acts were smaller: paying for the person in line behind them at a fast food place or bringing flowers to a coworker. My granddaughter Becca came up with the simple but brilliant ideas of putting a dollar bill in a baggie with one of the cards and taping it to a pop machine or leaving quarters by the vacuum cleaner at the car wash.

We relished seeing kindness done in Jacob’s name all over the country. Doing them ourselves helped us in our grieving. To this day, no matter how bad my day is going, performing one small act of kindness in Jacob’s name can brighten it.

If you’re looking for the warm glow from acts of generosity or a way to reduce your stress level so you can be more creative, searching for things you can be thankful for in your life is a great place to start.

IGNITE

Whether you decide to do your own random acts of kindness or begin a gratitude journal or jar, there are several books listed in the resource section that will help you get started. For the purpose of this activity, however, spend time literally counting your blessings. What are you grateful for in your life? What life experiences have made you a better person? When did you see good come from bad?

Create a Gratitude List: