Chapter 9:

WORD WORKMANSHIP

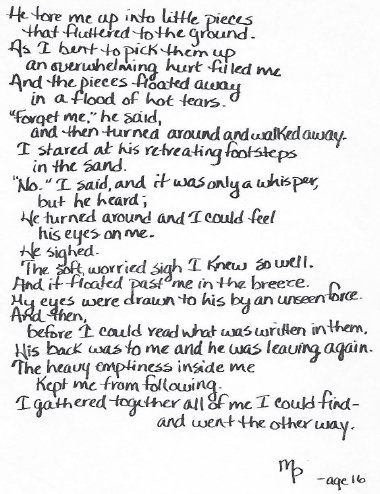

Poetry is an art form I dabbled in as a teen but never perfected. I wrote this poem shortly after my first boyfriend broke up with me through a note inside my high school locker one morning. The discovery left me an emotional wreck for the remainder of the day; I skipped most of my classes to cry in the bathroom until the bus arrived to carry me back home. Normally, town students were taken to the elementary school, but on this particular day, the bus driver took an alternate route, dropping me off at the bottom of the gravel hill to our driveway. I’ll never know for certain, but I suspect he couldn’t bear to hear the sobs or see the puffy, red-rimmed eyes of the teenage girl crouched miserably in the front seat behind him.

Dad was outside working on a vehicle when he was startled by the unexpected bus stop. My heart sank when I saw him walking down the driveway to meet me. I would have preferred telling my mother, but there he stood, blocking my route to the house. There was no avoiding it—unless I pushed past him, I would have to explain the hurt I’d experienced to a man who’d never been comfortable with expressing emotion.

“Steve broke up with me,” I managed to choke out as I thrust the crumpled, tear-stained note clutched in my hand toward him. Dad unfolded the paper and silently read it. I couldn’t meet his eyes, fully expecting him to break out into a lyrical rendition of “Feelings.”

“Feelings, nothing more than feelings,” he’d often mock my moodiness with the first lines of Morris Albert’s song. Instead, he surprised me by uncharacteristically reaching out to lift my chin, imparting some of the wisest advice I’ve ever gotten.

“I know it hurts and you can’t see it right now, but there will be other boys. And if he broke up with you that way and can’t see what a wonderful girl you are, then he didn’t deserve you anyway.”

When I so desperately needed understanding and compassion, my dad came through for me. I should have been penning poetry about a father’s stoic devotion instead of pining for what I’d mistaken as lost love, but alas, I was only sixteen.

The English word “poem,” or “poetry,” came from the Greek word poiema, which is translated as “workmanship” in Ephesians 2:10 in the Bible: “For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand that we should walk in them.” Essentially, we are God’s poetry, his masterpiece.

While my writing certainly hasn’t reached masterpiece level, it’s evident I do have a history of writing my way through difficult periods of my life, beginning with teen angst then through my husband’s cancer in 2006 to my mother’s death in 2010. I’d assumed the reason I turned to journaling as I mourned my husband was because I was a writer. Weeks into my grief journey, however, I wondered how anyone could survive the experience without writing about it.

In an attempt to understand my own, I began researching the topic of grief as though studying for a final exam: reading dozens of books and articles about the grieving process. In doing so, I stumbled across repeated references to expressive writing as a healing tool.

While diary-keeping is nothing new, the therapeutic potential of reflective writing came into vogue in the 1960s, when Dr. Ira Progoff, a psychologist in New York, began offering intensive journaling workshops and classes. He’d been using a “psychological notebook” method in his therapy clients for several years before that. In the 1970s, he wrote several books, including At a Journal Workshop, detailing his intensive journal process. Around the same time, Christina Baldwin released her book One to One: Self-Understanding through Journal Writing, based on the adult education journal classes she taught.

But it is Dr. James Pennebaker who is often lauded as the pioneer in studying expressive writing as a route to healing. Pennebaker, Regents Centennial Chair of Psychology at the University of Texas in Austin, discusses his findings in his book Opening Up: The Healing Power of Expressive Emotions, revealing how short-term, focused writing can have a beneficial effect for anyone dealing with stress or trauma. In his original study in the late 1980s, college students wrote for fifteen minutes total on four consecutive days about the most traumatic or upsetting experiences of their lives, while control subjects were instructed to write about superficial topics. Those in the experimental group showed marked improvement in immune system functioning and had fewer visits to the health center in the months following the study. Not only that, but despite an occasional initial increase in distress during the first session of writing, there was a marked improvement in their emotional health.

In another one of Pennebaker’s studies, fifty middle-aged professionals who were terminated from a large Dallas computer company were split into two groups. The first group wrote for thirty minutes a day, five days in a row, about their personal experience of being fired. The second group wrote for the same period of time on an unrelated topic. Within three months, 27 percent of the expressive writers had landed jobs compared with less than 5 percent of the participants in the control group.

Initially skeptical of Pennebaker’s remarkable findings, Dr. Edward J. Murray, a professor of psychology at the University of Miami, conducted his own investigations, eventually agreeing that writing seems to produce therapeutic benefits that include health, cognitive, self-esteem, and behavior changes. “Writing seems to produce as much therapeutic benefit as sessions with a psychotherapist,” he concluded.

Pennebaker’s original expressive writing paradigm has been replicated in hundreds of studies, each measuring different potential effects of expressive writing. Not only has subsequent research confirmed his original findings regarding physical well-being, writing about emotionally charged topics has been shown to improve mental health, reducing symptoms of depression or anxiety. This has proven true in studies with those who have experienced loss, veterans experiencing PTSD, and HIV and cancer patients. Expressive writing now seems to be an accepted alternative holistic and non-medicinal form of therapy for emotional health.

Pennebaker’s research did reveal that the type of writing mattered; there seemed little benefit to whining and venting without reflection. It was important to look for meaning in the experiences. He also discovered that healing writing didn’t have to be trauma-focused; writing about happy experiences and positive thoughts and feelings was also associated with health benefits.

None of this requires writing talent. There’s just something about putting pen to paper that is beneficial, whether it is journaling, blogging, or writing for publication. Even writing letters counts. In one study, Kent State professor Steven Toepfer discovered that having students write three letters a week, spending fifteen to twenty minutes on each letter, decreased depressive symptoms and increased happiness and life satisfaction significantly.

I experienced the letter-writing benefit after David’s death. Because he’d died on a Tuesday, I began dreading Tuesdays, a weekly reminder of my loss. When I made the decision to reach out to someone else every Tuesday, through a card or handwritten letter, I began looking forward to Tuesdays. Writing letters to others ending up helping me.

While I have maintained throughout this book that being more creative means opening up your mind, trying new things, allowing yourself to fail, and finding ways to work creativity in your everyday life, expressive writing is the one craft I have specifically and consciously honed since I was a teen. That served me well when I turned to writing to get through situations much tougher than a doomed teenage romance. The ease with which I wrote articles, essays, and even an entire book (Refined by Fire: A Journey of Grief and Grace) about the loss of my husband caused me to wonder why I hadn’t written more about Jacob, the grandson who died some seventeen months after his grandfather. It was as though I’d decided the loss was more my daughter’s and her husband’s, as the parents. I’d hesitated to claim it as my own.

Elizabeth had noticed. “You didn’t write enough about Jacob,” she’d lamented after reading Refined by Fire, and I’d replied that it was her story to tell. It wasn’t until working on this book, nearly five years after his death, that I wrote a poem about Jacob. I’d been encouraging members of a writing group I facilitated to enter a poetry contest. In turn, they challenged me to do the same. I struggled to write a poem about rubbing the feet of those I loved; first my dad when I was a child, then my husband’s during his cancer treatment, and, finally, my mother’s while she lay dying on her deathbed. I’d even chosen the title: “Love’s Disciple.” I wrote, revised, reworded, and rewrote again. I was ready to give up on poetry altogether when, almost as if it had a mind of its own, the words began flowing seamlessly and a new poem formed. A lump formed in my throat and tears stung my eyes. They were the same words I’d used in my book, but they somehow carried more power in the abbreviated poetry version.

Jacob I Have Loved

Tentatively, I approach

the small form hidden

beneath the blankets.

Standing silently,

I wait

straining to hear a breath,

to see the rise of a chest

expanded with vileness.

One small movement

reveals a thin arm

I reach out to touch,

skin hot and dry as paper.

I fall to my knees

in homage

of his holiness.

Head bowed close,

I whisper

“Tell your grandpa

I miss him.”

I don’t claim to be a poet; I have written perhaps a dozen poems in my life, including the one I penned at age sixteen. It wasn’t that Jacob’s poem was so well written, but something unexpected happened as I worked on it: I began sobbing, allowing myself to feel the full weight of sorrow at losing such a beautiful boy. As if for the first time, I claimed my loss and, in doing so, could begin healing.

I preach the therapeutic benefits of writing in my “Expressive Writing for Healing” workshops, but there is always the chance someone might think it works for me precisely because I am a writer by trade and that it is not applicable to them. But it was only through a form of writing I do not practice, poetry, that I experienced a mending of the gaping wound left by Jacob’s death. Now I can say with some certainty, even if you are not a writer, as I am not a poet, expressive writing can be a valuable tool in our arsenal against despair, as well as a creative outlet. And, as with any creative outlet, it takes time to develop the habit of creating.

In The Artists Way, author and creativity guru Julia Cameron claims a secret to productivity and getting rid of the clutter in your brain is to write every morning. “Morning Pages” practice means filling three blank pages of a notebook or journal with stream-of-consciousness writing first thing every day—a brain dump, so to speak.

“There is no wrong way to do Morning Pages,” Cameron says on her website. “They are not high art. They are not even ‘writing.’ They are about anything and everything that crosses your mind—and they are for your eyes only.”

Mark Levy calls it “freewriting” in his book Accidental Genius: Using Writing to Generate Your Best Ideas, Insight, and Content. In both cases, journaling and freewriting, the idea is to write as freely and as close to stream of consciousness as possible, freeing your mind so it can be more creative. That means no editing. At least not as long as the writing is for yourself. Eventually, you might want your writing to reach an audience through blogging or publication.

During my husband’s cancer treatment in 2006, I wrote daily while he was in the hospital after his surgery. After he was released, I wrote sporadically throughout the week—but consistently on Wednesdays, during his chemotherapy treatments. I’d sit next to him, holding his hand with my free one while I wrote with the other. What I wrote during those months, about cancer, caregiving, and what was happening in our marriage relationship, eventually became a book chronicling a true love story of a relationship renewed by caregiving, Chemo-Therapist: How Cancer Cured a Marriage. After David’s death, my “housewife writer” blog morphed into a grieving one for a while. I still get emails from widows and widowers thanking me for those posts that guide them in their own grief journey. Pieces of that blog and my private journal appear in Refined by Fire.

As a writer, however, there are times when I have trouble beginning an essay, article, or chapter of a book, moments when writing grinds to a halt. My husband used to quip “The hardest part is getting started,” and he was right. When I face those times, it helps to just sit down and begin writing, even if what I’m producing has little value and won’t make it into the final piece. I call it “greasing the writing wheels.” I might even begin a work session by writing a letter to a friend.

For writers, especially, it’s important to keep those wheels greased, to incorporate writing as a daily activity. Gretchen Rubin addresses this in her book The Happiness Project.

“Step by step, you make your way forward. That’s why practices such as daily writing exercise or keeping a daily blog can be so helpful. You see yourself do the work, which shows you that you can do the work. Progress is reassuring and inspiring; panic and despair set in when you find yourself getting nothing done day after day. One of the painful ironies of work life is that the anxiety of procrastination often makes people even less likely to buckle down in the future.”

“Day by day, we build our lives, and day by day, we can take steps toward making real the magnificent creations of our imaginations,” Rubin’s wisdom continues in her follow-up book, Happier at Home.

If you are new to expressive writing and would like to get started on the practice, these are suggestions I share in my Expressive Writing for Healing book and workshops:

1. Choose a notebook or journal that fits your personality, that you can comfortably write in. A beautiful leather-bound journal might be too intimidating to begin with. Perhaps it will be one with a cover design that has special meaning to you: a butterfly, a dragonfly, or a Bible verse. Or maybe you’d prefer a simple notebook with pages that can easily be torn out. Just the act of handwriting can be therapeutic, but if you’re more comfortable typing on a computer, that’s fine too. Choose whatever works for you and your lifestyle.

2. There are no rules in journal writing. Cross out sentences, scribble on the sides of the paper, doodle or draw on the pages. Don’t worry about sentence structure or grammar. This writing is for you and not an audience. You can’t help yourself if you’re holding back, afraid to be honest about what you’re feeling. Feelings and emotions can be messy, so it’s perfectly fine if your journal is too.

3. Write down your dreams, both literal and figurative. What do you want your more creative life to look like? Do you have dreams and desires for your future? Write them down. In a couple of years, you may look back and see some have become reality. Our subconscious also works hard at processing significant changes in our life. Have you had any particularly vivid nighttime dreams? Write those down too. I’ve experienced several dreams about David where I could feel his arms around me or hear his voice. I woke up feeling as though he’d actually visited me. I’ve also solved daytime dilemmas and come up with wonderful ideas in my dreams, so I like to keep a notebook by the bed to jot them down. I know better than to think I’ll remember in the morning.

4. If you are reading inspirational books or articles, copy passages or quotes that speak to you. When I read something particularly inspiring or uplifting that resonates with me, I transcribe pertinent passages or quotes in my journal. I often refer to those past journals and continue to find inspiration and encouragement from the words I copied down. That said, make sure the books and articles you read are bringing light to your soul. Just as our journal writing needs to focus on finding meaning in a situation, so should our reading. Be a discerning reader. There are too many inspirational and encouraging books available to bother reading one that makes you feel worse.

5. Date your journal entries, and end them on a positive note. We’ve learned how important gratitude is to our happiness and creativity. Strive to find one thing to be grateful for each time you journal. By ending your journal entry on a positive note—with words of thanks or perhaps a prayer—you are training yourself to consciously choose joy and gratitude. This practice works because it forces you to intentionally focus your attention on grateful thinking, eliminating unwanted, ungrateful thoughts and guarding against taking things or people for granted. You want gratitude to become a habit, so practicing it in your journal helps that happen.

“We write, we make music, we draw pictures, because we are listening for meaning, feeling for healing,” Madeleine L’Engle says in Walking on Water. “And during the writing of the story or the painting or the composing or singing or play, we are returned to that open creativity which was ours when we were children.”

Writing, just like painting, drawing, music, or photography, could be the workmanship you are designed for. If nothing else, it can serve as a form of meditation or a tool in your arsenal to help heal from those inevitable hurts we all experience in this life. All you need is a pencil and a piece of paper to begin.

“Creativity is a safe zone, and there is no place for self-judgement. While your mind might pipe in now and then, remind yourself that art is a path toward nurturing your self-expression and your happiest self.”

—REBECCA SCHWEIGER

IGNITE

Think you aren’t a writer? That you can’t benefit from creative or expressive writing? Think again! You don’t have to be a writer to pen your way through a tough time, just as you don’t have to be a poet to enjoy playing with words. You don’t even have to write the words yourself.

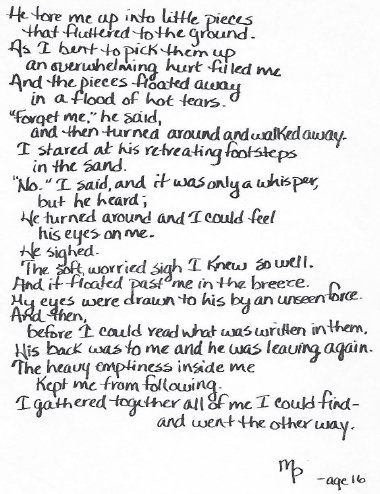

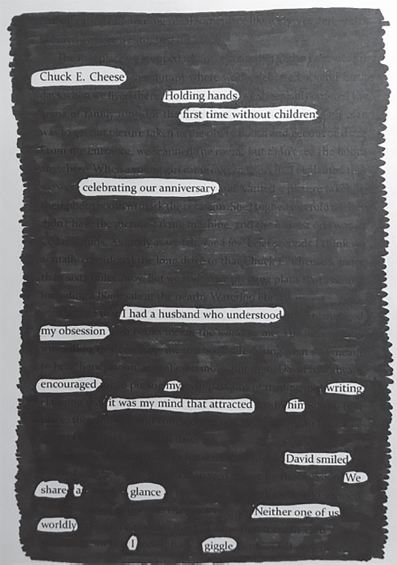

Let’s try blackout poetry. Turn out the lights and grab a flashlight. No, not really. Blackout poetry focuses on circling and arranging words that are already there on a page of previously published words, such as the page of a newspaper or book. Commonly attributed to author Austin Kleon, the practice entails using a permanent marker to cross out or eliminate words, keeping those words you choose. Kleon hit on the technique as a way of overcoming writer’s block, working with copies of The New York Times. His resulting blackout poems posted on his blog led to the release of his first book, Newspaper Blackout. Search the following page of text, emphasizing chosen words by blacking out the ones around them. It’s not necessary to read the page before you cross out words since the idea is to create a new work. Your resulting poem can be read from left to right or top to bottom.

You can find examples of blackout poems on Austin Kleon’s Newspaper Blackout website, https://newspaperblackout.com.

Mary’s first attempt at blackout poetry.

Use these two pages for your own blackout poetry.

What was it about couponing and refunding that appealed to me, and not to others? What got me started in this incredibly rewarding hobby? Certainly my mother had used a few coupons but never to any great extent. For one thing, she and my father could barely afford the newspapers or magazines that carried the coupons. As parents raising ten children on a low income, they struggled just to put food on the table and clothes on our backs. My father raised chickens for their eggs and meat and planted and tended a huge garden every year. My mother canned or froze their abundant harvest, sewed many of our clothes, made our dolls, braided rag rugs, and gutted the chickens that became a staple of our Sunday dinners.

If using coupons was simply a matter of saving money and the product of a person’s upbringing, then one would presume that most of my siblings, also raised in poverty, would be avid cou-poners as well. While they are frugal and shop thrift stores, of the ten of us, I was the only one that could be described as a coupon enthusiast until one sister joined me in the hobby last year.

Was it something innate in my personality then that attracted me to couponing and refunding? As a child I had the makings of a future coupon queen,

dissipated my fears. But on the night my mother passed away, my long-held fear of dying ceased. Perhaps it was the way she’d faced death or her anticipation to be with my father. Maybe it was watching my siblings gently care for her as she lay peacefully dying. After a lifetime struggle to impart her faith to her children, through her death, my mother had somehow managed to leave me a legacy of faith.

My mother had been a consummate artist and a highly creative woman. Having lived in poverty for most of her life, she didn’t have much in the way of material things. When it came time for my siblings and me to divide up her possessions, it was her art we coveted—the paintings, wood carvings, and handmade teddy bears. As the writer in the family, I became the “keeper of her words,” inheriting many of her notebooks and several unpublished manuscripts. I also had a thick memory book she’d filled out for me. During the months following her death, I read and reread her writing. With my husband’s blessing, I also spent many hours alone in her empty house that winter, working on a book. David encouraged my lone writing sessions, hugging me goodbye at the door and handing me a travel mug of hot tea he’d made me for the road.

During breaks from the intensity of writing, I’d push my chair back from my mother’s vintage oak