Chapter 12:

THE GREAT COLLABORATOR

After our mother’s house sold, I’d worried that the loss of my private writing retreat and her table would mean an end to the surge of creative energy I’d experienced in those three months. Instead, the intensity of those weeks of writing sessions only served to invigorate me, practicing creativity begetting even more creativity. As I discovered, meeting with other creatives can do the same thing.

“Finding like-minded creative friends is important for those seminal imaginative sparks to catch fire,” Grant Faulkner writes in Pep Talks for Writers. “‘None of us is as smart as all of us,’ the saying goes. An initial idea grows through the interchange of ideas, with one idea sparking another idea—and then the light bulb of inspiration glows.”

Investing time and money into a writing conference in the summer of 2011 was a big step for me. With an agent pitching my completed manuscript, it may have been the first time I considered myself a “real” writer, despite the fact that I’d been selling articles and essays for more than twenty years. With the investment, I was primed to learn more about the business side of publishing and what it is to join a community of writers who are willing to share ideas and experiences, encouraging each other. Garnering like-minded friends and a mentor in Shelly Beach was just an added bonus. David reveled in the writing I was doing and the relationships I’d formed. You would have thought all of it was of his making.

A series of awe-inspiring events that followed my husband’s death led me to my second mentor, Cecil Murphey, an author whose book 90 Minutes in Heaven David had read and recommended to me.

It was unusual for David to be the one to recommend a book. I’d always been the reader in our marriage, and until that last year of his life, he counted on me to choose his reading material: books by Philip Gulley, Bill Bryson, and Dave Barry and biographies of famous people. It was completely out of character, then, when in the months preceding his death, David began reading books by televangelist Joyce Meyer. I knew he’d been watching her on television, so I shouldn’t have been surprised. Most mornings I came downstairs to find him already on the couch, watching one of her broadcasts. Though he’d ask me to join him, I usually headed straight to the kitchen to get some writing in before the kids woke up. What did he find so appealing about her message that he’d also wanted to read her books? I remember watching with him only once, when curiosity had gotten the best of me.

It was just weeks before he died. We sat on the couch next to each other, holding hands. I immediately saw the appeal in Joyce’s down-to-earth attitude. I found her to be a dynamic speaker, so I was taken aback when David suddenly turned to me, proclaiming I would someday “be like her.” Though I’d done a few workshops by then, I never imagined becoming a public speaker. Then he scrutinized my hair. “And I want you to go to the hairdresser as often as you need, to look good for your public.”

I was flabbergasted. My husband was imagining something I couldn’t fathom: believing not only that I would someday be a speaker but that I’d have a public. As for the hair comment, apparently before I’d joined him on the couch, Joyce had discussed her frequent visits to the hairdresser. To this day, I can rationalize hairstylist visits before a big event, knowing my husband would have approved.

When David had a heart attack in mid-March, I brought several books and magazines to the hospital for him to read, but he’d waved them away, saying he didn’t have the energy. The day before he was to be released, he asked about the book I’d brought for myself.

“Leave that for me,” he said when I told him the title. I was surprised, since he’d made it clear up to then that he hadn’t wanted any reading material. When I packed his things for home the next morning, the book was on top of a nearby shelf. I never asked, and he didn’t mention it, so I’ll never know if he actually read any of it, but I do know Getting to Heaven by Cecil Murphey and Don Piper was the last book David touched.

Three days after his return from the hospital, my husband died during the night. When the mail was delivered to my house that morning, someone retrieved it from the mailbox, dropping it in my lap. Numbly, I thumbed through it. Beside greeting cards from David’s siblings for what would have been his birthday the following day, there was an envelope from Cecil Murphey’s assistant, Twila Belk. Inside was a check for $50 along with notification that an essay I wrote would be appearing in an anthology compiled by Murphey and Belk. Two days later, on the evening of my husband’s wake, I received an email awarding me a Cecil Murphey scholarship for the upcoming Write-to-Publish writing conference in Wheaton, Illinois. When I’d filled out the application, I’d asked David what we would do if I won, since the conference ended on our June anniversary.

“There will be other anniversaries,” he’d commented, insisting I apply.

My first contact with the man whose name kept appearing in my life would be an exchange of emails in which I explained my recent loss and his return reassurance that I could use the scholarship another year, if needed. I finally decided it would be easiest to spend my first lone wedding anniversary away from my home, doing something David had wanted for me. I never imagined the conference would be more a spiritual than educational experience.

While I’d prayed and asked God to pair me up with another widow in the dorm room, he knew better what I needed. My roommate was a woman who’d never married or had children. While friendly enough, she left me completely to my own devices, which allowed me quiet and solitude. She seemed completely oblivious to the tear-stained cheeks I woke up with (inexplicably escaping from my eyes as I slept) or my muffled sobs into a washcloth in the shower on the morning of what would have been my anniversary. Nor was she in the room anytime I wanted breathing space between sessions. Much of the conference was a blur in grief-induced fog, but certain moments remain crystal clear.

I remember the beautiful music that began each morning and had me bolting from the room in tears. I’ll never forget author Jane Rubietta who found me in the hallway and took hold of my hands to pray for me, or Cynthia Ruchti’s workshop that I ended up in by accident, with a message I copied down so I can share it now. “Life . . . even with its distressing parts . . . feeds our words and ignites our stories. God doesn’t waste anything. Let the Lord use it. God will refresh you and revive you,” she said as a lump formed in my throat and tears filled my eyes. “Brave writers all write from a dwelling place, or a history of pain. Mine the pain. Don’t waste it. Use it.”

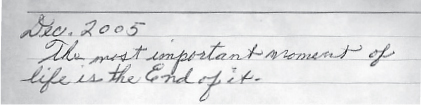

I don’t have to search my memory for the sign I discovered the final day of the conference because I’ve saved it as a reminder. The piece of paper—that hadn’t been there just moments before—was attached to a tree on a pathway that reminded me of the University of Northern Iowa campus I’d walked with David the previous year. The handwritten sign declared: If a tree does not suffer great winds and storms, its bark will not grow thick and strong. The tree, thin, naked, and weak, will fall over and die. Storms will bring strength, majesty, and growth. God brings storms to build us. When He builds us, we will go forward. I carefully removed it from the bark, certain its message was meant for my wounded soul, just as that morning’s guest pastor’s devotional had been.

“I see you, Mary.” His booming voice startled me at the back of the room, and his eyes seemed to look straight into mine, yet I’d never met him and was convinced he’d chosen a random common name. “I see you, Mary. Take courage. Be filled with courage. Every follower of Jesus Christ can survive their deep water and dark night experiences because we have the knot of reassurance that even when we can’t see Jesus, Jesus sees us. ‘I am here. I am here for you,’ he says. Don’t be afraid to take the next step.”

Thanks to the conference, I knew my next step: I’d be writing a book about grief.

That fall, I traveled to the Maranatha Christian Writers’ Conference to personally meet and thank the man who was responsible for the scholarship I’d won. I arrived at the conference just before the evening meal was to be served. The coordinator left me in the empty cafeteria, assuring me other attendees would soon be there. I filled a cup of coffee and set it at an empty table in front of a chair where I placed my purse. My back to the tables, I slowly began filling a plate from the buffet. When I turned around, I saw that a man with a full head of white hair had taken the seat next to the one I’d claimed. I’d seen photos of Cecil Murphey. Surely it couldn’t be possible that with all those empty tables and chairs in the room, he’d somehow chosen the one next to mine?

He glanced up as I approached, and I gasped.

“Cecil Murphey? I can’t believe it! You’re the person I’ve come here to see!” When I clasped his outstretched hand, I swore I felt an immediate jolt of recognition, as if our souls already knew each other. In the next few days, I took several of his workshops, learning from a writing pro and observing a speaking style that was uncannily similar to that of our mutual friend Shelly Beach. Shelly had arranged for Cec and I to share an evening meal, an overnight stay at the same bed and breakfast, and a ride to the airport the next morning. By the time I hugged him goodbye, I’d gained another mentor and friend.

Six months later, Cec’s wife died. A year ahead of him in grief, I yearned to help my new friend down a path I’d already traveled. While I’d been writing to him occasionally, I amped up the frequency of my letters. I sent him books I’d found helpful and pieces of my work in progress, the book I’d begun at the conference his scholarship had gifted me with. Our friendship was strengthened by this bond of mutual loss, and Cec would eventually write the foreword for that book. The year after it was released, my new mentor was the keynote speaker for the Cedar Falls conference. While in Iowa, he officiated at the backyard wedding of my son Dan and his fiancée, Lydia.

When I discovered Cec would be returning to Iowa in April 2016 and was searching for speaking engagements while here, I was stunned to realize the timing of his visit would coincide with a grief speech I’d been contracted for a year in advance. The coordinator readily accepted the addition of the famous author as a co-speaker.

The opportunity to speak with my mentor was a dream come true. I had no doubt that an outline and our similar speaking styles would guide us in meshing our grief stories. A practice session at a small church gathering the night before went well. We said a prayer together before we stepped on stage the next evening for the big event.

Something extraordinary happened during the final portion of the speech with my mentor. At one point I distinctly remember wondering where my words were coming from. I saw several people in the audience wiping away tears as I spoke. When Cec gently tugged at my sleeve to indicate we needed to culminate the presentation, I protested lightly. When he leaned over and whispered that I’d been talking for twenty minutes, I was astonished, realizing there was no time for our planned wrap-up. Cec deftly closed with some final remarks. A group of women approached me as he headed to the hallway where a display of our books was set up.

“I wish he hadn’t stopped you,” one woman said, and the others nodded. “You were saying exactly what I needed to hear.”

I almost asked her what I’d said, as I had no recollection. Instead, I listened to their concerns and answered their questions for another half hour. By the time I made it to the sales table, the crowd had dissipated. When Cec apologized for cutting me short, I confidently assured him that whoever needed to hear more had stayed behind. I didn’t explain what had happened, because I wasn’t sure myself. While I’d experienced something similar with my writing on occasion—when something outside of myself takes over—this was the first time I’d experienced it with a speech. It wouldn’t be the last. When it does happen, I thank God for the phenomenal occurrence. While it sounds lofty (Oh, that wasn’t me talking—that was God), it is the opposite. It is acknowledging that I couldn’t possibly be responsible for my successes on my own. Instead, I’ve allowed the Holy Spirit to lead. I’ve since discovered others have experienced the same thing.

“Have you ever had a moment when you knew you were awesome? I know you are not supposed to say that, but have you ever thought it? You know, that moment when everything just came together. You were in perfect form,” Erwin McManus writes in The Artisan Soul. “Athletes call it ‘the zone’; in other disciplines they call it ‘finding your flow.’ As a speaker, it’s the moment when you don’t even have to think. The words seemingly form themselves.”

Thomas Kinkade experienced it while painting. “The more deeply involved I become in the act of creation, however, the more I have the sense that the most creative work I do is not really my own—that the ideas and the expression come from outside or beyond me. At times I’ve had the sense that I was holding the brush but that a power outside myself was guiding my hand,” he wrote in Lightposts for Living.

“You may know this feeling. It’s the feeling you get when you’ve made something wonderful, or done something wonderful, and when you look back at it later, all you can say is: ‘I don’t even know where that came from,’” Elizabeth Gilbert writes in The Big Magic. “Sometimes, when I’m in the midst of writing, I feel like I am suddenly walking on one of those moving sidewalks that you find in a big airport terminal; I still have a long slog to my gate, and my baggage is still heavy, but I can feel myself being gently propelled by some exterior force. Something is carrying me along—something powerful and generous—and that something is decidedly not me.”

This is what can happen when our work becomes a form of worship with the Creator as our collaborator. In Walking on Water, Madeleine L’Engle described her process of writing this way: “To work on a book is for me very much the same thing as to pray. Both involve discipline. If the artist works only when he feels like it, he’s not apt to build up much of a body of work. Inspiration far more often comes during the work than before it, because the largest part of the job of the artist is to listen to the work and go where it tells him to go.”

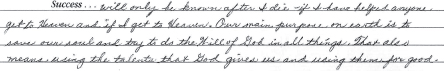

Most of us will probably not make a living from our creative endeavors. There’s a reason I keep a day job, which offers its own opportunities for creativity and innovation. Some readers will have been fortunate to discover a purpose in life during their youth. Others will have struggled for years to become what they are meant to become, holding down dead-end jobs or fighting frustration as they valiantly attempt to stoke that tiny flame that burns within. Then there are those facing the tail end of life, restless with the certainty that there is something yet to be accomplished. The remaining, like my mother and great-aunt Christine, already incorporate creativity and faith in every part of their lives.

“Every day God invites us on the same kind of adventure. It’s not a trip where He sends us a rigid itinerary, He simply invites us. God asks what it is He’s made us to love, what it is that captures our attention, what feeds that deep indescribable need of our souls to experience the richness of the world He made. And then, leaning over us, He whispers, ‘Let’s go do that together,’” Bob Goff, founder of Love Does, once wrote.

In the end, my mother’s life had been her finest masterpiece, her legacy.

What will yours be?