Introduction:

A MOTHER’S MASTERPIECE

Our main purpose on Earth is to save our soul and try to do the will of God in all things. That also means using the talents He gave us and using them for good.

The words were my mother’s, written repeatedly in her notebooks and a memory book, but they would become mine in the months and years following her death in November 2010.

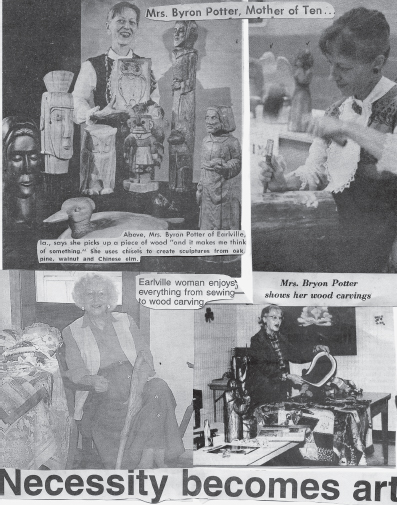

My mother had lived an extremely creative life, partly by necessity, more by invention. Raising ten children in abject poverty, she beautified her home with colorful rag rugs and quilts made from scraps of material. She sewed tiny denim jumpers out of her own skirts and teddy bears from cast-off woolen coats. She managed to fill twelve hungry bellies by gutting chickens, gathering eggs, canning and freezing produce, and inventing half a dozen ways to incorporate tomatoes and potatoes into recipes. Then, during her spare time, she’d draw pastel pictures, carve beautiful wooden statues, and paint on barn boards, selling many of these creations as a home business.

By the world’s standards, Mom left little of material value behind. When my siblings and I divided her things, it was the remaining wood carvings, paintings, homemade teddy bears, and quilts that each of us wanted.

No one objected when I claimed the notebooks my mother had written in at night while sitting at the dining room table. Nor did they complain when I carted home four or five versions of each of her three unpublished manuscripts or idea files she’d constructed from brown paper sacks sewn together in crude scrapbook form. As the writer in the family, it seemed apt I would become the “keeper of her words.”

I can admit now that I’d also coveted her dining room table, but it went to my youngest sister, Jane.

I spent a lot of time alone in my mother’s empty house during the weeks following her death, sitting at that table, praying and writing. All winter, and well into the spring, I utilized the house, reveling in the unaccustomed silence. During breaks from writing, I’d pore over the remaining boxes of her possessions, searching for and using them for good. clues to the enigma of a mother who’d managed to spend a lifetime practicing her varied talents.

Words collided with images from a distant past as I wrote my way through that winter. I worked in a fog of grief that brought memories of my mother and me to the forefront: the two of us at parallel play, sitting on the front porch, her with art and me with words. She would paint, sew, or carve something beautiful from a piece of wood while my teenaged self wrote angst-filled poetry or short stories. Once, we were both painting in companionable silence when we heard a noise at the entrance to the porch. My father stood there, taping a handwritten sign on the window of the closed door. Caution. Artists at work. Don’t enter these premises unless you are talented, he’d scrawled in red ink. Years later, Mom framed the torn and wrinkled sign and gave it to me. For Mary, one of the artists on the premises. From Mom, the other one, she’d written in pencil on the back.

I worked on many projects in my mother’s house that “winter of discontent.” Ten miles from home, I’d found the room of my own that Virginia Woolf had insisted every female writer needed. I managed to accomplish as much in twelve weeks writing at my mother’s table as I had in the previous twelve months at home. I credited the solitude, Mom’s creative spirit, and perhaps the table itself for my productivity, worrying it would all dissipate once the house sold and the table was delivered to my sister.

It didn’t. If anything, immersing myself in creativity begat even more creativity. In the year following the sale of the house, I attended my first two writers’ conferences, planned and implemented a writing course for homeschooled teens, and designed another course for adults. I conducted workshops at local community colleges, which resulted in a weekly column for an area newspaper. Several of my essays were accepted for anthologies, and I began doing public speaking.

“My mother never doubted for a moment that each of her children had talent,” I began in one of my first speeches. I’d been asked to speak on creativity to a room full of young homeschooling moms. “Do you believe the same thing about yours?”

The women nodded, smiling with pride.

“Do you encourage your children’s natural gifts and spend money on lessons or training?”

Again came the nods. I paused before asking, “But what about you? Do you ever doubt your own inherent creativity?”

Their smiles faded. Suddenly, they couldn’t meet my eyes.

A few months later, I did the same presentation for a group of women at the other end of the spectrum, empty-nesters and retirees. When I asked about their talents, their replies were heartbreaking, ranging from “I don’t have any talent” to “It’s too late for me now.”

There’s a book in this somewhere, I thought then. Once home, I made notes that I filed in a folder labeled “Creativity.”

Seven years and five books later, during an equally discontented winter, when I was miserable at a job that should have been perfect for me, I spent a morning reading letters my mother had written to me during the 1980s and early 1990s, letters I hadn’t looked at since. Before long, I was shaking with sobs.

What was wrong? Had cumulative grief finally caught up with me? I’d lost my mother in 2010, my husband in 2012, and my grandson the following year. But as I continued to read her letters, I realized it was the unmistakable message repeated in them: Utilize your talents. Follow God.

Was I utilizing my talents working for a newspaper? Writing stories on agriculture and farming topics, covering legislative coffees, school board, and supervisor meetings? I was assigned the occasional human interest story, but those were few and far between. Because of my work hours, I’d lost my own morning writing time, dropped the writing classes I’d taught at community colleges, and said no to most workshops and public speaking opportunities. I’d given up those things that brought me joy in exchange for a paycheck and health insurance.

I’d been spending a lot of time with God that winter, too, asking what He wanted me to do. When a library job with fewer hours and more free mornings was advertised, I took a leap of faith and applied for it. When I was offered the position, I was nearly giddy with excitement over the idea of having some free mornings. Unsure what the topic of my next book would be, I knew I’d be writing one.

My mother’s letters continued speaking to me. I dug deeper into the trunk where I kept them, unearthing some of her notebooks, the memory book, and a binder full of articles about her, along with photographs of her art. I was fascinated with the woman who went by Mrs. Byron Potter for all her magazine subscriptions, bills, and much of her business correspondence. She remained Mrs. Byron Potter until the day she died, and nearly eight years after her death I continued to get her junk mail, addressed to the wife of Byron. My father died in 1986.

Upon further reflection, it occurred to me that she’d claimed an identity separate from her husband and children in only one aspect of her life after marriage: her artwork. While her initial wall hangings and pastel drawings were signed “I. Potter” or “Irma Potter,” at some point, perhaps around the time she began selling pieces, she chose an artist name. In a newspaper interview, she told the reporter she chose the name Amy because it meant “beloved,” and Amy was the creative sister in her favorite book, Little Women. When Mrs. Byron Potter (Irma Rose) registered “Rustics by Amy” at the county courthouse, she began signing her paintings and wood carvings “Amy.”

The winter reminiscing contributed to an increased restlessness within me. I wanted to embark on a creative project. The week after I changed jobs, I submitted an article to a magazine and wrote two essays for anthologies. But I yearned for something more, something bigger. Was it perhaps time to resurrect that creativity book?

On March 11, 2017, I filled my last journal with my husband’s face printed on the cover. While he was still alive, I’d ordered journals personalized with photos of the two of us together and the words Grow old along with me. Five years out from his death, it was a relief to finally fill the last one, to not look one more time at the quote that had become a taunt. We can invite someone to grow old with us but cannot demand it.

I retrieved a new journal from my cupboard, one with a photo image of my mother’s table on the cover. Opening it up, I discovered I’d begun writing in it the month after she’d died but had forgotten about it. A dozen pages were filled with quotes on creativity.

I was certain then of my next project: I’d be writing about the artisan soul each of us is born with. I pulled out the file folder I’d set aside nearly seven years earlier and pored over the contents, increasingly excited about delving into a topic that had meant so much to my mother. I made copious notes in my new journal. By April, I was ready to begin work on the book proposal. I emailed the publisher of my previous books to ask if he’d be interested in seeing it upon completion. He responded in the affirmative.

That very afternoon, my sister Jane called. After a few minutes of casual conversation, her voice changed, catching a little as she got to the point of her call.

“You know we’re moving soon, to a smaller house,” she began.

I felt a little prickle at the back of my neck.

She hesitated before continuing, sounding near tears. “I don’t know why, but I feel like I’m supposed to give you Mom’s table, that it’s meant to be with you. Do you want it?”

Of course, the answer was yes. It was only after I hung up that it dawned on me: not only would I be writing a book in honor of my mother’s legacy of creativity—I’d be writing it at her table.