APPENDIX 5B

GOOD, BETTER, AND BEST MEASURES OF TARGET LIQUIDITY

The following seven measures of target liquidity may be used by a nonprofit organization, with the higher-numbered measures being best (but recognize that if you are using supplemental information you could use a lower-numbered measure to arrive at a liquidity position approximately consistent with #7). We do not include any permanently restricted cash or short-term investments in these calculations. For background and development of these measures and related concepts, see Chapters 7 and 8. The authors acknowledge their debt of gratitude to Lilly Endowment, Inc., for its funding of the original study by John Zietlow, from which the concept and primacy of target liquidity emerged.

- Target cash = Amount in checking account

- Target cash and equivalents = Amount in checking account + Short-term investments up to 3 months in maturity

or = Target cash + Investments up to 3 months in maturity

- Target cash and equivalents and short-term investments = Amount in checking account + Short-term investments up to 3 months in maturity + Short-term investments from 3 months to 1 year in maturity or = Target cash and equivalents + Short-term investments from 3 months to 1 year in maturity

- Target liquid reserve = Amount in checking account + Short-term investments up to 3 months in maturity + Short-term investments from 3 months to 1 year in maturity + Available portion of credit line

or = Target cash and equivalents and short-term investments + Available portion of credit line

- Target net liquid balance = Amount in checking account + Short-term investments up to 3 months in maturity + Short-term investments from 3 months to 1 year in maturity – Credit line balance* – Current portion of long-term debt

or = Target cash and equivalents and short-term investments – Credit line balance – Current portion of long-term debt

- Target net liquid reserve balance** = Amount in checking account + Short-term investments up to 3 months in maturity + Short-term investments from 3 months to 1 year in maturity + Total amount of credit line – Credit line balance – Current portion of long-term debt

or = Target liquid reserve – Current portion of long-term debt

- Target lambda-based liquid reserve*** = Amount in checking account + Short-term investments up to 3 months in maturity + Short-term investments from 3 months to 1 year in maturity + Available portion of credit line

or = Target cash and equivalents and short-term investments + Available portion of credit line

Note: This liquid reserve measure differs from the target liquid reserve in that it is determined mathematically from the target liquidity level lambda (TLLL) instead of judgmentally (subjectively).

Notes:

- * Credit line balance is typically listed as either the credit line or as short-term notes payable on the Statement of Financial Position (or Balance Sheet).

- ** Not a previously developed measure; derived by taking the net liquid balance and adding the total amount of the credit line to the current financial assets before subtracting the credit line amount used and the current portion of long-term debt.

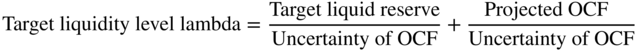

- *** Derived and calculated as follows from the lambda measure, renamed the target liquidity level lambda in John Zietlow, Jo Ann Hankin, and Alan G. Seidner, Financial Management for Nonprofit Organizations (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 217–219: Lambda = (Liquid reserve + Projected operating cash flow) / Uncertainty of operating cash flow

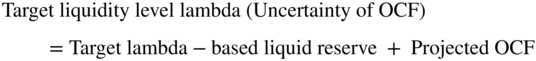

Rephrasing to denote target amounts, abbreviating operating cash flow as OCF, and rearranging terms on the right-hand side:

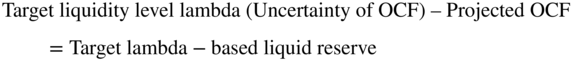

To solve for target liquid reserve, multiply all terms on both sides by uncertainty of OCF, then subtract projected OCF from both sides:

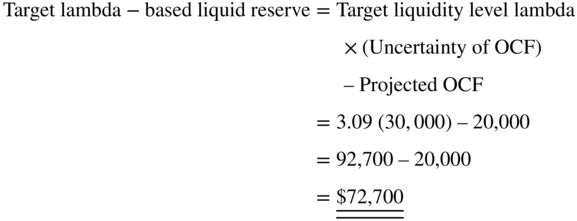

For example, if the organization targets a lambda value (target liquidity level lambda, or TLLL) of 3.09 (representing a 1/10 of 1 percent probability of running out of cash within the selected one-year time horizon), the annual operating cash flow's standard deviation (uncertainty) is $30,000, and its projected operating cash flow is $20,000, the organization's target liquid reserve (cash plus short-term investments plus unused credit line) is determined as follows:

The implied cash and short-term investments target may then be calculated. First, note that the liquid reserve is cash plus cash equivalents plus other short-term investments plus unused credit line. If the organization has a credit line of $50,000 presently carrying a $0 balance, it would need cash and short-term investments of only $72,700 – $50,000 = $22,700. Recognize that the lambda measure is based on variability of annual cash flows but does not reflect the possibility of additional upward or downward spikes within the year. To the extent that the organization's cash inflows and cash outflows are unmatched during the year, due to heavy seasonal or within-month outflows, the organization might choose to override this estimate and hold most of the $72,700 in cash and short-term investments.

Alternatively, one could measure lambda for a shorter time horizon; one must adjust the projected operating cash flow to match that horizon, as well as calculate the standard deviation per that same period (if one uses the next month's projected operating cash flow, the standard deviation of monthly cash flows must be used in the denominator). If an organization has a credit line, it is logical to use an annual time horizon, as credit lines are negotiated annually.

Source: Copyright © 2008, 2011, 2018 by John Zietlow. All rights reserved worldwide.