CHAPTER 11

CASH MANAGEMENT AND BANKING RELATIONS

- 11.1 INTRODUCTION

- 11.2 WHAT IS CASH MANAGEMENT?

- 11.3 COLLECTION SYSTEMS: MANAGING AND ACCELERATING RECEIPT OF FUNDS

- 11.4 DISBURSEMENTS

- 11.5 STRUCTURING A FUNDS MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

- 11.6 MONITORING BANK BALANCES AND TRANSACTIONS

- 11.7 CASH FORECASTING

- 11.8 SHORT-TERM BORROWING

- 11.9 SHORT-TERM INVESTING

- 11.10 BENCHMARKING TREASURY FUNCTIONS

- 11.11 UPGRADING THE CALIBER OF TREASURY PROFESSIONALS

- 11.12 SECURITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT ISSUES

- 11.13 TRENDS IN TREASURY MANAGEMENT

- APPENDIX 11A: DIRECT PAYMENT FOR NONPROFITS

- APPENDIX 11B: DIRECT PAYMENT CASE STUDY

11.1 INTRODUCTION

When managing cash and cash flow to achieve your organization's target liquidity, proficiency in cash and treasury management is essential. The organization awarded the 2017 Association for Financial Professionals (AFP) Pinnacle Award Grand Prize for Excellence in Treasury and Finance was World Vision International, a faith-based child sponsorship nonprofit. Your organization may also aspire to excellence in this crucial business function.

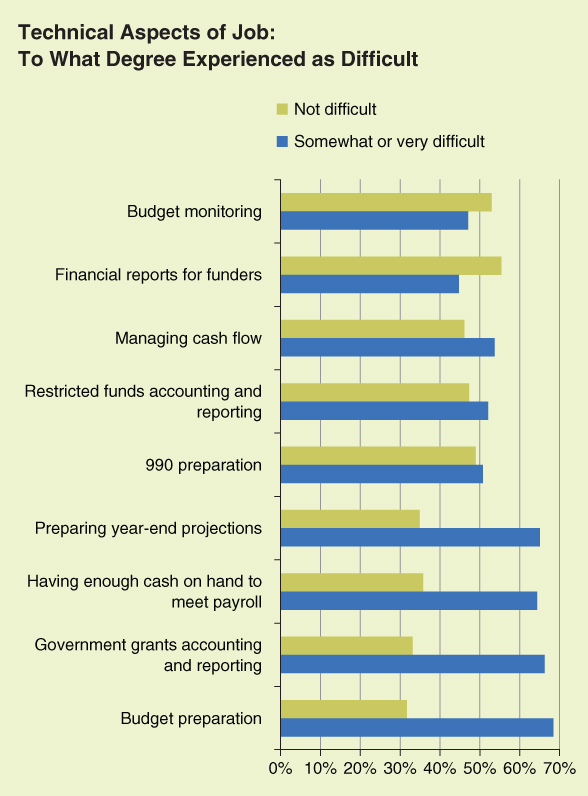

The US cash management environment is one in which check usage and the cost of information technology are on the decline, and interest rates and the use of electronic payments are on the upswing. Consider the opportunities to use cloud-based technologies for accounting, banking, cash forecasting, and investing, and you have a recipe for remarkable improvements in nonprofit cash management. And improvements are needed to help prevent cash crunches and financial crises for many nonprofits: CFOs report that one of their most challenging roles is “having enough cash on hand to meet payroll,” with “preparing year-end projections” being almost as challenging, and “managing cash flow” not too far behind in perceived difficulty (see Exhibit 11.1).

Source: Steven D. Zimmerman and Jan Masaoka, “Adding It All Up: Nonprofit CFO Study.” Located online at: www.blueavocado.org/content/adding-it-all-nonprofit-cfo-study. Accessed: 7/11/17. Used by permission.

Exhibit 11.1 Nonprofit Chief Financial Officers' Difficult Job Tasks

Fundraising and foundation or membership relationships are central to many nonprofit organizations. For most outside of education and healthcare, the treasury function primarily revolves around collecting, handling, and managing cash gifts, foundation grants, and membership dues. For education, healthcare, and other nonprofits, managing liquidity to support borrowing and investing decisions is also vital to ensure funding for the nonprofit's varied activities. For yet others, trying to bridge the gap until government grants or contracts get disbursed and received is the primary challenge. Having funder monies restricted to programs further intensifies the cash flow difficulties of many nonprofits.1 Today it has become increasingly important for these functions to be carried out efficiently to maximize resources and control costs. Treasury responsibilities have evolved from paper-based, manual processes to highly automated and sophisticated systems that interface seamlessly with banks, service providers, and other internal operating units.

Cash management is a subset of treasury management, and it involves the collection, mobilization, and disbursement of cash within a nonprofit enterprise. Moving funds and managing the information related to the funds' flows and balances are fundamental to good cash management. With a strong understanding of the banking system and the products and services offered by banks, the cash manager can achieve effective mobilization of funds, prudent investing of these funds, and cost-effectiveness in services used.

Depending on its size and scope of activities, a nonprofit's financial structure may range from simple to highly sophisticated. In any case, a system needs to be designed to monitor the cash flow timeline that links revenue/cash receipts and purchasing/cash disbursements. For some, transactions can be more complex when cash flows cover large payrolls, sizable inventories, vehicle fleets, and other supplies for an organization like the Red Cross or a major healthcare facility with heavy financing and working capital needs.

A comprehensive understanding of an organization's operational processes is basic to structuring a sound cash management program. Identifying and quantifying the activities, interfaces, and resources that make up the collective cash flow can lead to a better assessment of service requirements for banks and other financial services providers. Significant advances in technology have had an impact on the delivery of cash management services and offered numerous opportunities for managing deposits, funds concentration, disbursements, and information and control. As new applications have emerged, automated and computerized processing capabilities have replaced paper-based information and inquiry systems. Cash managers now use the Internet, cloud-based treasury or bank software services, and/or computerized treasury workstations (which are actually just specialized software packages) to execute transactions and gather information ranging from bank balances to investment transactions and other financial activities. Processes that required manual intervention are now routinely handled by innovative electronic collection, concentration, and disbursement applications. Cash management activities are being carried out better, faster, and more cheaply. With increased productivity through automation and “cloud” systems, there are many opportunities for cash managers to add value and enhance service support to other parts of the organization. With nonprofits expected to do more with less, outsourcing possibilities should be considered alongside traditional approaches. A good example here is establishing a temporary lockbox service with a bank or third-party provider to handle the annual fund donation flow, which then is turned off by the bank after all donations are received.

The primary goal of this section is to identify the trends and opportunities that nonprofits should consider to enhance treasury functions relating to cash management. Our context here, as throughout the book, is to maintain adequate liquidity in order that our organization has the right amount of cash, available at the right time, without overpaying to have that money available, and spends it according to mission and donor purposes. Put more formally, we wish “to ensure that financial resources are available when needed, as needed, and at reasonable cost, and are protected from financial impairment and spent according to mission and donor purposes” (as noted in Chapter 2). We achieve this by adept and prudent cash management. This, in turn, entails using the appropriate collection, concentration, and disbursement tools.

Collection and disbursement mechanics that have benefited from technological advances will be highlighted in this chapter, along with regulatory and banking developments. Identifying electronic systems for accelerating the collection of remittances and controlling disbursements to ensure timely and orderly outflows will be explored. Then, the strategy for identifying, selecting, and working with the right bank or financial service provider will be addressed. What is the bank's breadth of product, systems, and service levels? How committed is the bank to maintaining and improving its product and service offerings? How important is my account to the bank? Will the bank continue to show special attention to our industry? What is the bank's financial strength? With the right financial services provider(s) as partner(s) and the appropriate technology to support operations, many benefits and opportunities can be maximized. Throughout the remainder of the chapter, we will refer to all depository service providers as “banks.” Do not limit your selection menu to banks, however. There are credit unions that are pursuing nonprofit relationships, and they are worth a careful look, especially if you have localized financial service needs.

11.2 WHAT IS CASH MANAGEMENT?

Cash management encompasses a number of activities within these primary functions:

- Cash collection

- Cash concentration

- Cash disbursements

- Investment of surplus cash, if any

- Financing or borrowing, if needed

- Forecasting cash flows

- Managing bank relations

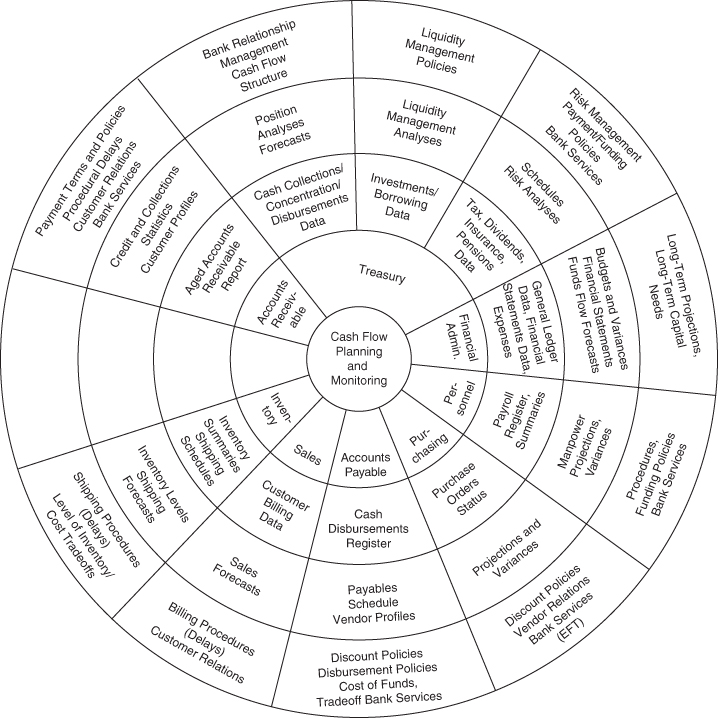

The fiduciary responsibility of nonprofits must be balanced in the way business is conducted. Financial risks should be recognized and appropriate measures taken to safeguard assets. In designing and structuring a good cash management program, distinguishing day-to-day functions from strategic objectives is important. At the same time, focusing on efficiency must take into account control and flexibility in managing cash, based on a strong understanding of organizational cash flows (see Exhibit 11.2).

Source: Aviva Rice, “Improving Cash Flow Control Throughout the Corporation.” © 1997 by the Association for Financial Professionals, all rights reserved. Used with permission of the Association for Financial Professionals.

Exhibit 11.2 Comprehensive Cash Flow Management

(a) BANKING ENVIRONMENT. Commercial banks serve as depositories for cash and also act as paying and receiving agents for checks and other fund transfers.

Banks have been a traditional source of financing for short- and medium-term needs, providers of investment services, fiduciary/trust services, and global custody.

A number of financial institutions now have dedicated nonprofit departments or groups, and their specialization may be a significant advantage for your organization. Illustrating, the Evangelical Christian Credit Union (Brea, California), the Bank of the West, and Huntington Bank (Ohio) specialize in making facility, equipment, and other loans to nonprofits. SunTrust, The National Bank of Indianapolis, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, KeyBank, and others have nonprofit departments. It makes sense to find out how extensive the nonprofit client base is: Huntington Bank advertises that it has 700 nonprofit clients in a six-state Midwest region.

Building a good relationship and partnership with the right bank offers many advantages. A growing nonprofit organization will benefit from the right association and could leverage such a relationship to integrate services such as cash management, trust, capital markets, and credit. With few exceptions, a full-service commercial bank can offer a range of cash management services that will meet all the requirements of your nonprofit. Smaller banks such as The National Bank of Indianapolis, sometimes dubbed “community banks,” may value nonprofits more, may offer a special mix of services, and often have better pricing. In certain situations, unbundling services and seeking out multibank relationships may be appropriate where services are required in different geographic regions of the country or even overseas. International banking is offered by many major banks, and specialized needs for foreign exchange, letters of credit, and other international transactions are easily met. Pricing, quality of service, support, and technology are factors that must be considered in deciding on a single or multibank setup. Technology for cash concentration can link multiple accounts in different banking relationships without slowing cash transfers or incurring added expense. What value-added benefits can be realized in a single or multibank relationship is a question that needs to be explored. Services Provided by Treasury Management Banks

| Account reconciliation | Information reporting |

| Automated clearinghouse (ACH) services | Retail lockbox |

| Check clearing | Wholesale lockbox |

| Positive pay and reverse positive pay | Sweep accounts |

| Controlled disbursement | Treasury management software |

| Demand deposit accounts | Wire transfers |

| Electronic bill presentment and collection | Zero balance accounts |

(b) PURCHASING BANK SERVICES. When purchasing bank services, a formalized approach will help you ensure that important decision factors are not overlooked in the evaluation and purchase of cash management services. You may wish to use an informal or partial request for a product or service in certain situations. However, there are potential disadvantages to such a process that can be eliminated through the use of two suggested critical steps: a request for information (RFI) and a request for proposal (RFP). As we prepare to discuss the RFI and RFP, consider the steps involved in changing banks, including implementation, profiled in Exhibit 11.3.

Source: Brian Welch, “Changing Your Cash Management Bank,” Global Treasury News (June 23, 2000). Used by permission.

Exhibit 11.3 Reasons for Changing Banks and How to Proceed

The RFI is part of a structured information-gathering effort to identify potential vendors and their product offerings. Through trade directories, publications, referrals, and annual rankings,2 this informal process can provide data on banks and vendors that will include such information as experience, technological capabilities, and creditworthiness. This process could potentially eliminate the need for an RFP when there is clearly one superior vendor or when specific service requirements can be met by only one or two vendors. While not optimal, this approach provides a basis for a more informed decision than one based solely on previous relationships and price. At least once every few years, an RFI is helpful in comparing capabilities outside of an existing relationship and staying current with changes in the industry.

An RFP is the next step to take when soliciting bids for several cash services and a comprehensive search is warranted. The process can be fairly involved and time-consuming. Key to an RFP would be a statement of the nonprofit's objective in soliciting the proposal. This would include:

- A description of the service sought

- The preferred location(s)

- The volume of transactions by service (measure costs under various activity volumes)

Exhibit 11.4 provides an outline of a sample RFP for lockbox processing. In addition, specific service requirements should also be addressed in an RFP:

Source: From James S. Sagner and Larry A. Marks, “A Formalized Approach to Purchasing Cash Management Services,” Sagner/Marks, Inc., Journal of Cash Management 13, no. 6 (November–December 1993).

Exhibit 11.4 Sample RFP: Lockbox Processing

- Any special features or customization required

- Level of support service expected (who, hours, level of authority)

- Problem-resolution procedures

- Automation capabilities

- Mechanisms for funds transfer

- Availability of information (cutoff times, cost)

- Level of quality expected

- Pricing information; pro forma account analysis giving total dollar charges based on anticipated usage of each service

- Questions relating to product-specific issues and buyer requirements for special transaction requirements

- Deadline for response

- References (do a thorough check)

- Contact person

Spelling out both general and specific qualifications and requirements will provide a more objective approach and meaningful comparison of service levels. Corporate practitioners recommend meeting with potential banks at the beginning of the process to go over required services and then at the end of the process after the selection is made. When the best bank (or other vendor) is identified, the next step is to secure a commitment in writing and document the details and fees involved. This should also include deviations from the RFP, specific computations, price commitment, change notification periods, cost of uncollected funds, overdrafts, and daylight overdraft provisions. Use of a matrix that scores the responses from banks or vendors is recommended.

In putting together an RFP, questions can be organized from the general to the specific. Exhibit 11.5 contains examples of methods that may be used.

Source: From James S. Sagner and Larry A. Marks, “A Formalized Approach to Purchasing Cash Management Services,” Sagner/Marks, Inc., Journal of Cash Management 13, no. 6 (November–December 1993).

Exhibit 11.5 RFP Questions

For assistance in preparing RFPs for banking services, Nilly Essaides at the Association for Financial Professionals (AFP) has developed a publication to help in selecting cash management banks. How to Conduct a Successful RFP for Banking Services, published by AFP under the sponsorship of KeyBank, provides an outstanding list of tips and practices for conducting an RFP from start to finish.3 Detailed RFPs are available from AFP (https://www.afponline.org/publications-data-tools/data-tools/rfp-resource-center) for these cash management services for a nominal fee:

- 401(k) Plan Bundled Provider RFP (can be customized to 403(b))

- Automated Clearing House (ACH)

- Controlled Disbursement

- Custody Services

- Depository Services

- Disbursement Outsourcing

- E-Banking and Information Reporting

- Electronic Data Interchange (EDI)

- Global Treasury Services

- Merchant Card Services

- Paycard

- Purchase Card Services

- Remote Deposit Services

- Retail Lockbox

- Short-Term Investment Management

- Treasury Technology

- Wholesale Lockbox

- Wire Transfer

Steps should be taken to build and strengthen the relationship once a vendor is selected and a contract signed. Keeping the account officer well informed of activities, changing requirements, operational processes, policies, and future plans is fundamental. Giving honest feedback also ensures a productive partnership. In the long run, negotiations are made easier, and the account officer becomes very knowledgeable about the nonprofit's operations. The account officer's input can be a resource in identifying opportunities for improvement. Developing a consultative partnership can be useful in analyzing treasury functions and getting valuable suggestions for process improvement. An annual review between banker and client completes the process toward constructive relationship building.

What can the cash manager and banker do to get the most from a bank relationship? What are each other's expectations and objectives? Are they attainable and reasonable? Building a relationship requires a real investment of time for all parties involved. Strategies for relationship building are premised largely on trust, open communications, honest feedback, and team building. Setting realistic objectives is fundamental and provides the framework for implementing agreed-on procedures and service requirements. When a client calls a banker only when a problem arises, the relationship stands on shaky ground. Regular meetings and follow-ups ensure open communication. With the rise in bank mergers, takeovers, and consolidations, managing a relationship has become increasingly challenging. The consistency in quality, service, and price that a client seeks in a bank tends to be disrupted as bank cultures change and personnel turnover creates dislocations. When a strong relationship has been cultivated, problems and uncertainties will be more manageable and less stressful to handle. A win-win situation is a likely by-product of a healthy relationship. Finally, we concur with Tom Fraser of First Federal Savings & Loan in Lakewood, Ohio, who notes that there is ample and valuable advice available from your banker:

Your banker should act as a trusted adviser. For example, bankers have experience with cash flow cycles and expansion opportunities, so they can readily help with early advisory initiatives for financing – and they don't charge hourly like CPAs and attorneys. It's also often more economical to work consistently with your primary bank because you're already sharing information.4

(c) MANAGING BANK SERVICE CHARGES. What does it cost to do business with your bank? How are balances determined? What are the reserve requirements? What is the basis for calculating the earnings credit rate? Are all the services needed? How should the services be paid – by fees, balances, or a combination of both? Answers to these questions can be gathered from an account analysis statement, which presents a clear picture of bank services and account status. This monthly invoice contains two separate sections on balance and service information. It is critical to understand the account analysis statement and its terms and components to verify the accuracy and level of charges. Understanding the services used and relating this usage to the pattern of collections and disbursements could lead to potential cost savings. When multiple banks are used, comparisons using spreadsheets would be necessary on a monthly basis.5 Basic to the analysis are:

- Cutoff, preparation, and timing of analysis statement by bank

- Bank service charges organized by type of service: depository, remittance banking, reporting, disbursement, lending

The balance section should be reviewed in terms of where the information comes from, the type of activity, and the service charge associated with each activity. Reconciliation helps ensure accurate and timely assessment of balances. How best to compensate the bank can also be answered when investment alternatives offer higher rates of return than the earnings credit rate (ECR; sometimes called an earnings credit allowance or earnings allowance rate) that banks may automatically apply to collected balances. In such a scenario, paying by fees may be more advantageous when one can invest collected balances and earn a higher interest income.

Computation of the ECR may be tied to a market rate, such as the 90-day Treasury bill rate, or a managed rate determined by the bank based on various factors, such as cost of funds and competitive pressures. The formula for calculating an ECR must consider the impact of the reserve requirement on bank charges; the 10 percent reserve requirement reduces the balance receiving the earnings credit by 10 percent. Additionally, deposit insurance may also be charged as a “hard charge” fee based on balances held in the account; when added together, both costs significantly lower balance levels. In considering payment by fees or balances, compensation to banks must be analyzed and negotiated to understand which arrangement is cost-effective. A clear agreement must be in place to identify the method and timing of compensation, especially if a method other than monthly settlement is preferable. Banks prefer monthly settlement, but when balances are used for compensation, quarterly, semiannual, or annual settlements may be appropriate to maximize use of excess balances that occur within the settlement cycle. Carrying forward excess balances must be negotiated, and the time period should be stated. Whenever settlement occurs, deficiencies should be billed and may be debited directly from the checking account.

Auditing and reviewing the account analysis statement could spot price changes and potentially identify cost-cutting opportunities. Working together with the bank relationship manager, a review may suggest ways to cut bank costs that are more directly tied to how the cash management system operates. Examples would include:

- Payment alternatives. Paying by ACH is cheaper than wire transfers, and using PC-initiated wire transfers is cheaper than phone-initiated transfers. Organizations are using same-day ACH to make last-minute bill payments or for emergency payroll.

- Account maintenance. Combine or eliminate checking accounts, since $4 to $50 can be charged each month per account (and this does not include per-item fees on related services such as for each check paid).

- Checks deposited. Consider encoding or sorting checks if volumes are high or doing remote deposit capture if volumes are low. On-site remote scanning with electronic transmission of items to be deposited is cost-effective for most organizations.

- Stop payments. Use an automated system.

- Account reconciliation. Use a paid-only (partial) reconciliation service instead of a full account reconciliation program.

Refer to Exhibit 11.6 for definitions of terms used in an account analysis statement and Exhibit 11.7 for a description of the components of the account analysis statement. If your organization is not presently “on analysis” (“analyzed checking”) at your bank, check with your bank relationship officer to see if being being switched to analyzed checking might reduce your fees or increase your interest income.

Exhibit 11.6 Definitions of Terms Used in an Account Analysis Statement

Exhibit 11.7 Components of the Account Analysis Statement

11.3 COLLECTION SYSTEMS: MANAGING AND ACCELERATING RECEIPT OF FUNDS

Electronic collection, technically called direct payment if the amount is taken out of one's account on an ongoing and preauthorized basis without a card being used, is slowly replacing checks as the payment of choice. Surprisingly, in 2015 there were still 17 billion check payments made per year in the United States (down from almost 20 billion in 2012).6 Although donations are still collected largely from checks mailed by donors, electronic payment options are gaining acceptance. This acceptance has been influenced by factors such as an increase in comfort with electronic products, personal convenience, and an increased sense of security about the medium. Cash substitutes in the form of debit and prepaid cards, direct payments through the ACH, and ACH debits are growing. The ACH is basically a computerized network for processing electronic debits and credits between banks for their customers through the Federal Reserve System. A dedicated website is now available for nonprofits considering the advantages of direct payment (electronic collection of donations using the ACH system): https://electronicpayments.nacha.org/donor. Appendix 11A provides a Direct Payment for Nonprofits guide, and Appendix 11B provides a nonprofit direct payment case study for you to review. Most US households now use direct payment and, on the whole, are very satisfied with it. In fact, US consumers now pay more than 800 million bills per month using direct payment via ACH.7

Credit card and debit card payments are also used increasingly but may cost more than checks or ACH payments, depending on the transaction size. Electronic transmittal of credit card and debit card transactions offers cost advantages over paper-based processing with the potential for a reduced discount rate (the charge levied by the merchant bank) and direct credit to the organization's bank account. Upon transmission, notification is immediately provided on any discrepancy in account information by a payor or disallowed transaction (e.g., credit limit exceeded). As the volume of credit card and debit card payments increases, an annual review should be conducted. Keeping track of card amounts and activity will be helpful in negotiating a lower discount rate since merchant banks base their pricing on average ticket size and volume.

When agreements are in place to collect pledges using an ACH or other electronic payments, the cash forecast is significantly improved. Money becomes available at the agreed-on monthly or quarterly interval. Within hours from initiation of an ACH debit, funds will be credited to the organization's checking account or swept to its concentration account. Credit card transactions can be collected within one to three days. The percentage of collections handled through check substitutes is still low but is gaining acceptance. The experience of nonprofits that have used ACH debits (also called automatic bill payment, automatic debit, electronic bill payment, or direct debit) suggests that a pilot test and survey must first be conducted to gauge the willingness of donors to participate in such a program. One foundation has been using ACH debits for quarterly payment of its annual fund pledge payments. Specifying a cutoff amount that will be cost-effective to handle is also recommended, and it is advisable to start with a focus group or payment type. The process saves staff time, postage costs, and other expenses associated with issuing pledge reminders and invoices. One large ministry organization determined that the average cost of donation processing if made by ACH debit was 22 cents; if made by check, 80 cents; and if made by credit card, $1.42.8

Exhibit 11.8 shows that the relatively new ACH same-day payments innovation is meeting competition provided by private parties for immediate or same-day transfers. The second one listed, the RTP system which is run by banks (“The Clearing House”), took only three seconds to settle its first transaction. As noted earlier, organizations are using same-day ACH for last minute bill payment and for emergency payroll. Check with your bank to see whether ACH same-day payments are your best option, or if one of these new entrants offers a cost-effective, secure alternative for collecting from your donors or other payors.

Source: “Introduction to Faster Payments in the U.S.,” NACHA, April 2017. Used by permission. Available at https://resourcecenter.nacha.org/sites/resourcecenter.nacha.org/files/resource/NACHA_Intro_To_Faster_Payments.pdf. Accessed: 7/11/17.

Exhibit 11.8 Same-Day and Real-Time Payments in the United States

An ACH credit is a payment choice for more and more corporations that have matching gift programs for their employees. The ABC Educational Foundation signed up for a pharmaceutical company's matching gift program and now receives a direct payment to its bank checking account. Like any other automated transaction, the payment is clearly identified and shows up in the bank balance report. For beneficiary distributions to planned giving donors, the foundation makes monthly or quarterly payments by ACH. This replaced check payments that required more staff time to process. A donor's financial institution or bank does not charge for ACH remittances, unlike a wire transfer, which could cost $10 to $15 to receive.

Check collections can also be accelerated through pre-encoding the amount in the magnetic ink character recognition line or presorting by drawee bank locally, by city or region. Using these two options, depositors can avail themselves of preferential pricing and better availability from their banks. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve's same-day settlement (SDS) initiative permits a collecting bank to present items to any paying bank directly, without establishing a relationship with that bank or paying presentment fees. SDS has spurred electronic clearing mechanisms.

Electronic check presentment and check truncation have grown rapidly due to legislative provision for an “image replacement document” to be electronically transmitted and be considered the legal equivalent to a paper check when presented to the bank on which the original check was drawn. This has revolutionized check collection by clearing checks and identifying return items using data transmissions rather than moving paper checks. Nearly all the checks received by and then cleared by the Federal Reserve (Fed) in the U.S. are in the form of electronic check images, and the Fed handles all check collections at one location rather than the 45 locations it had at one time. Combined with image processing, information on returned checks and access to gift data can be gathered sooner and at less cost.

(a) LOCKBOX PROCESSING. The lockbox system was developed to accelerate check collection and expedite deposit of accounts receivable. The concept began 60 years ago with the recommendation to use a post office box (lockbox) to collect large-dollar remittances. A corporation, through an authorization letter to the postmaster, permits a designated bank to extract mail from the corporation's box around the clock. With frequent pickups throughout the day, a bank can process remittances faster compared to directing mail to company premises. The objective is to minimize mail and processing time so that checks are converted into available funds more rapidly.

Many nonprofits today use lockbox services to process gift checks, membership dues, and other receivables associated with marketing and merchandising activities. You may opt to have the lockbox service opened for only part of the year, when your inflow of mailed checks is highest. In addition to banks, other service providers now offer lockbox processing. Current generations of lockbox services employ automated production interfaces, including bar code technology to receive and sort the mail; automation to encode, endorse, and photocopy checks; high-speed capture of payor bank routing information; and Internet access to confirm balance and receivables information. As noted earlier, checks are converted to electronic images to allow them to be presented quickly for payment to the drawee bank.

If outsourcing collection processing makes sense, a lockbox service should be evaluated. In selecting a vendor, these factors must be considered:

- Types of plans offered

- Vendor's operational capability

- Automation

- Professional staff (years of experience, turnover)

- Quality-control checkpoints (low error rates)

- Number of pickup times per day (but make sure this translates into a better availability schedule and/or later cutoff times)

- Availability schedule (when do deposits become available for investing, for paying down loans, or for funding disbursements?)

- Support and problem-resolution responsiveness

- Cutoff times (how late can you get the checks and still have them count for ledger credit?) and weekend processing

- Pricing

- Reporting capabilities

- Interface with accounts receivable system or an integrated accounting software system

- Disaster and continuity provisions

In using a lockbox service, the cash manager should coordinate with other departments' specifications relating to invoices and other remittance material. These specifications may include image-ready invoice redesign, proper ink colors, background print elimination, proper specifications for window envelopes, use of bar coding, and strategic location of key pieces of information (donor identification numbers, mail zip codes, return address). The cash management account officer of the bank or vendor should be consulted for assistance in designing the remittance document to providing more efficient processing and data capture in an electronic format. Reporting can also be streamlined so that the appropriate service plan can be identified and the pertinent information can be captured. Otherwise, the cost can be high.

Advances in imaging technology allowed replacement of costly printouts for lockbox remittance information that take longer to produce and deliver. Image technology captures details on invoice data, donor name, address, or dollar amount, and eliminate the need for stapling the invoice, envelope, and check photocopy. Information can be captured electronically and the image transmitted over the Internet. Data can be sorted, and users can store large volumes of data. Backup storage can take place to the cloud. The database is accessible from multiple locations, possibly via an intranet or over the Internet, and can automatically route information to various points within an organization. A development officer inquiring about a donor's gift can access a file containing the image of the check and the solicitation document. Both can be transmitted through e-mail or accessed through the organization's database.

Outsourcing through a lockbox service has its advantages and is an option that merits comparison against internal processing. Your finance team must evaluate the cost and staffing associated with internal processing, notably peak-period demands as well as the break-even receivable size. In cases where check or receivables processing is close to full capacity, this limits the internal processing facility's flexibility in bringing in trained personnel at peak periods, and outsourcing may be worth considering.

(b) CHECKLIST OF COLLECTIONS-RELATED SERVICES AND ACTIVITIES. This list of collections-related services and activities holds promise for nonprofits, based on our experience and our conversations with banking professionals:

- Get the checks out of the inbox! Too many nonprofits allow time to elapse between the point when donors or clients mail the checks and when those checks are deposited and become spendable funds at the bank. Changes in the US payment system regarding check processing have greatly reduced the float time for those using electronic deposits, as noted by the Federal Reserve:

Checks are now effectively all processed electronically once they enter the banking system and are increasingly being scanned and deposited electronically by businesses, often using accounting applications, and individual payees using mobile devices. Some checks are taken out of the check clearing process and converted to ACH payments, but the practice has not grown since electronic check processing took hold.9

If you cannot or do not prefer to improve your processes on your own, enlist the help of another organization or a financial institution. ChildFund, an international relief and development agency located in Richmond, Virginia, is a superb example of this. Treasurer Bill Hopkins located a nonbank company that had worked to expedite check collections in-house and had excess capacity. Now ChildFund authorizes the processing company to pick up checks received at ChildFund's post office boxes, pre-encode the checks with the dollar amounts and image those checks, and make the check deposits at ChildFund's bank. For the checks ChildFund receives at its offices, it scans and images them and transmits the check deposits to its bank daily.

- Use lockbox services. Many other large nonprofits tap bank or other third-party lockbox services in which donors' checks are received at a dedicated post office box, which is emptied by processor couriers 15 to 20 times a day and then taken to a specialized check processing operations center for automated document and check processing. Organizations get possible reductions in mail float and assured reductions in processing float and availability float in return for the monthly fee the processor charges. SunTrust and some other banks offer a service for organizations that have high check deposit volumes only twice a year during fundraising campaigns, allowing a minimal maintenance lockbox fee to be assessed during the months in which the service is not being used. Your organization may also elect to use a lockbox service during its capital campaign.

- Use check truncation and check conversion. Check truncation and check conversion (point-of-sale conversion of a check to an electronic debit, being used by some healthcare organizations, and lockbox accounts receivable conversion [ARC] of mailed checks to electronic debits) are cutting the processing delay as well as the availability delay for having spendable funds.

- Learn about image capture. Here you feed checks into a scanner-like device attached to your PC and convert them to images, which you then transmit as an electronic deposit to your bank from the location and at the time you choose. “Electronic depositing augments the migration toward paperless banking, using remote capture technology to process images as opposed to the actual paper checks,” explains Georgette Cipolla, vice president of product development and product management at Fifth Third Bank. “Whether our customers receive checks by mail, in a drop box, or over the counter, they can deposit them from the security of their own office, significantly reducing the time, effort, and resources expended on remittance processing.” You may also be able to deposit items later in the day – Wells Fargo allows customers to electronically deposit as late as 7:00 p.m. Pacific time.

- Consider pre-encoding deposits before transporting them to the bank. This process, in which you imprint the dollar amount of the checks on them in magnetic ink, makes sense for organizations having at least 4,000 or 5,000 checks in their monthly deposits, according to William Michels, assistant vice president of global treasury management sales for KeyBank in Cleveland, Ohio. This gets the organization reduced fees or better availability.

- Utilize banks' deposit reconciliation services. Here special deposit tickets cause your deposits from various branches in a geographic region to get deposited into one account (discussed in more depth later in the chapter). This gives you automatic funds concentration and location-by-location accounting. Furthermore, check out zero balance accounts (ZBAs), which allow your deposits in various locations to be transferred via bookkeeping entries to a master account at the same bank that same day without individual transfer fees. You may avoid transfer fees as well as multiple investment sweep fees (discussed later) by using ZBAs.

11.4 DISBURSEMENTS

Just as speeding collections is a recognized cash management tool, so too is the control of disbursements. Disbursements in the form of checks and drafts typically include all payments a nonprofit makes in the course of doing business. These may include payroll, vendor payments, grants, and distributions, to name a few.

(a) DESIGNING THE DISBURSEMENT SYSTEM. A well-planned disbursements system includes well-defined, systematic, and accurate procedures for authorizing, generating, and accounting for payments. Whether a system is paper-based, as with the use of checks, or electronic wire transfers and ACH, the cash manager's task is to orchestrate all the elements of checks, bank services, and the check-clearing process to monitor and control the outflow of funds. A sound disbursement system will help maximize the working capital funds available and enhance overall liquidity.

The disbursement function is handled primarily through bank checking accounts. In the past, delaying payment clearing time has been a technique employed to maximize disbursement float – the amount of time that elapses from the moment a check is released to the moment a check is charged to the issuer's account. This disbursement float consists of the sum of mail float, processing float, and clearing float. Managing float is less relevant in a low-interest-rate environment (but will become more important when interest rates trend upward). Furthermore, with electronic payment mechanisms and image exchange of checks, float is being largely eliminated from the US payments system.

(b) FRAUD AND INTERNAL CONTROL IN DISBURSEMENTS. Effective check disbursement practices are important for all organizations since many rely on checks as a payment mechanism. The treasury professional will be well served to have check disbursement controls in place to avoid fraud and potential losses. These recommendations for internal control should be built into treasury operations:

- Implement stringent disbursement approval, release, and stop-pay procedures.

- Ensure that only authorized personnel are performing these functions and that all procedures are documented and kept up-to-date.

- Secure check stock and facsimile signature plates. Remove check stock from printing equipment and store in a locked location when not in use.

- Maintain current signature card and bank agreement files. Update authorized signatories for all organizational and bank network changes. Notify bank of approved signatories on a periodic basis to ensure accuracy of records. Conduct periodic reviews to verify that currently used bank services and all applicable laws are reflected in bank agreements.

- Segregate the disbursement and account reconciliation duties of staff.

- Perform timely checking account reconciliations, preferably before the next month-end.

- Implement stringent voided check procedures. Punch out the signature on the voided check and promptly void the check in the accounts payable system.

- Consider using bank or internal automated account reconciliation, and almost all organizations should use a bank's positive pay services (discussed in more depth later).

- Stay on top of fraud issues related to remote capture of donors' or customers' checks.10

- Conduct periodic treasury/internal audit review.

11.5 STRUCTURING A FUNDS MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

The use of a general bank account or a set of accounts for deposits and disbursements is a decision that varies from one nonprofit to another. The choice is largely dictated by the type, size, and complexity of transactions associated with the nonprofit organization's activities. A well-designed bank account configuration is needed to maximize flow of funds, enhance earnings, improve efficiency, and facilitate better control of financial resources.

Cash concentration and controlled disbursement accounts are two cash management structures that separate the collection and disbursement of funds. If multiple locations deposit funds, cash concentration can be accomplished electronically through the Federal Reserve's ACH system. A cash concentration service will transfer funds from any financial institution in the country to a designated bank where the concentration is centralized. Transfers can be prepared at specified cutoff times each day, and funds will be available in one business day. This service offers a number of benefits: It eliminates idle funds in local depository accounts, speeds up identification of available cash, provides the potential for increased earnings on investments or reduced interest costs on debt as a result of funds centralization, enhances control over funds, facilitates quick decision making through timely receipt of deposit information, and provides data for monitoring deposits and balances.

Controlled disbursement eliminates guesswork from daily funding requirements on checks presented for payment. Through a controlled disbursement account, checks are paid through one or more disbursement accounts. Information on checks presented for payment is reported sometime late morning each day, and automatic transfers are made from a checking account to cover the day's disbursement activity. This service can reduce overdrafts and the use of credit lines. With computerized reporting, accurate data collection is possible, and clerical workload can be reduced through automatic funding and reporting.

Another cash management tool for disbursement and concentration is an automated zero balance account. The process links any number of disbursement or depository accounts. At the end of business each day, all balances over designated cash levels are transferred to a concentration account. Conversely, all balances below the designated level are automatically covered by transfers from a concentration account. Funds transfers from and to a single concentration account are handled automatically, and balances in disbursement and depository accounts can be set at a target amount or at zero. By eliminating idle balances in accounts and centralizing cash, better control will reduce overdrafts and increase efficiency in managing cash.

11.6 MONITORING BANK BALANCES AND TRANSACTIONS

Accurate and timely information on cash balances is essential to managing liquidity and making critical financial decisions about the use of funds. Today information on bank transactions, deposits, payments, return items, and other activities is readily accessible through a wide variety of mechanisms. These range from manual reporting by voice operator and touchtone devices to online access to balance data. Account reconciliation services help your organization “balance its checkbook.”

(a) BALANCE REPORTING AND TRANSACTION INITIATION. Bank-balance reporting is a product that conveniently provides the cash manager access to bank account activity and information. Using a computer, web browser access to a bank's portal can be automatically programmed to gather balance information from as many banks as required or manually initiated. Balance reports include current ledger and collected balances, deposits subject to one- and two-day availability, error adjustments and resolutions, balance history, and average balance over previous time periods. Details of debits and credits, lockbox transactions, borrowing and investments, concentration reports, and other transactions can also be downloaded.

In addition to information retrieval, online initiation of transactions such as wire transfers and ACH payments is now possible. Services can be customized and expanded as needs change. Security features include passwords and multiple levels of identification codes, along with some new handheld devices. The use of cash management and information systems offers many benefits in terms of monitoring and controlling account activity, locating cash surpluses or shortages for more productive use of funds, enhancing cash forecasting, allowing stop payments, and reducing clerical time and expense in tracking cash positions. Investment activity and foreign exchange reporting can also be downloaded using bank information systems.

Automated information systems are widely available and competitively priced. They offer convenience and efficiency in cash management, and nonprofits are well served to use them. Information gathering is significantly enhanced, and the demand for timely information by management and trustees can be satisfied.

(b) ACCOUNT RECONCILIATION. Timely and accurate reconciliation of check payments is now effectively handled through account reconciliation services. Many banks offer a full or partial account reconciliation service to provide accounting on the status of checks issued. This can include paid, outstanding, exception, stopped, voided, or canceled items. Use of the service helps to balance an account faster, improves audit control, and provides protection against unauthorized, altered, and stopped checks. This service is most advantageous when a significant number of checks is written each month. It can simplify bookkeeping procedures and reduce staff time in balancing accounts.

Deposit reconciliation is another application suited to nonprofits with multiple locations depositing into a single account. The service segregates deposits by location and lists nonreporting locations. Through special serial-number groupings, daily reporting, and comprehensive monthly reports, the service facilitates auditing and enhances control over local depository activity. At the same time, the convenience and economy of a single depository account can be retained.

An invaluable service now offered by banks is positive pay. This option provides daily access for authenticating check payment by comparing checks issued to checks paid. A bank provides a daily list of nonmatching checks paid, and an exception is submitted to the organization. Instruction for payment or return of checks on the list can be given to ensure payment of legitimate checks only. This service is another tool for controlling fraud and is accessible online with the bank.

Overdrafts are likely to occur without a reliable cash forecasting and balance reporting system. Timely information on the status of disbursing accounts will enable a cash manager to move funds and avoid overdrafts. Monitoring funds availability is also important to minimize ledger overdrafts. When overdrafts occur, there are costs incurred aside from the interest expense charge or one-time fee that is assessed. Opportunity costs arise in terms of income lost from foregone investments, costs associated with transferring funds, and costs of delayed payments on bills (lost discounts, ill will, and other related costs). For a nonprofit institution making distributions to planned giving donors, donor relation issues are very sensitive, and accuracy is critical. Arrangements for overdraft protection or a line of credit would be advisable.

Aside from normal overdrafts, daylight overdrafts occur when funds are not sufficient to cover a transfer although the negative balance is covered by the end of the day. With Federal Reserve policy discouraging daylight overdrafts, banks pass charges to their customers. To avoid daylight overdrafts, accounts should be monitored intraday. Wire payment outflows can be timed to correspond with the availability of Fed funds from incoming transactions. Another technique is to match the method of payment with the source of covering funds. For example, wires and ACH payments settle differently, and it would be costly to rely on ACH deposits that may not be available to cover the amounts of outbound wires.

11.7 CASH FORECASTING

The cash management practice we see as the most ripe for improvement in the nonprofit world is cash forecasting. An organization is hindered in numerous ways when not having an updated forecast of forthcoming cash inflows, outflows, and the resulting cash position. Three results we observe often are:

- Spending cash that would have been held had one foreseen that a seasonal “dry period” was ahead

- Holding minimal cash reserves due to ignorance regarding the cash drain attending program growth

- Holding large cash reserves and giving up interest yield because too large a portion of the organization's funds is held in overnight investments or a demand deposit account

Treasury Strategies finds that companies that forecast cash positions and also base their investment maturity selection on the forecast earn an additional 31 basis points in yield per year (about of 1 percent).11 We expect nonprofits would earn this same additional yield.

Cash forecasting is a valuable treasury tool. It begins with a definition of objectives for the forecast and a realistic assessment of the structure and activities of an organization. Forecasting allows management to evaluate changing conditions and formulate appropriate financial strategies. As a planning tool, cash forecasts (also called cash budgets) have to be monitored and updated to reflect both short- and long-term variables. (See Chapter 8 for more on cash budgeting.)

Depending on a nonprofit's funding and operational needs, cash forecasts can determine optimal borrowing and investment strategies. Many nonprofits rely on gift contributions for funding, and their timing is difficult to project. Accordingly, gathering information from internal sources is more predictable, particularly with the expense side of the equation. Common sources of receipt data are a nonprofit's sales (or program) units and accounts receivable departments. Disbursement data would come from those responsible for purchasing and accounts payable, as well as the human resources area for payroll and benefits data.

(a) CASH SCHEDULING. For some organizations, a monthly cash forecast does not give enough detail, and cash scheduling may be a more relevant technique in determining the organization's short-term cash position (one day to six weeks). The process begins with a forecast of deposits to plan the timing and amount of funds for cash concentration. Simultaneously, estimates are made on when checks will be presented. When concentration and disbursement accounts are used, cash scheduling will help the cash manager to mobilize funds without experiencing the opportunity costs associated with excess and idle balances. Ideally, balances can be maintained at target levels in the appropriate concentration or disbursement account.

(b) DATA ELEMENTS FOR CASH FLOW ESTIMATES. Receipt and disbursement items vary among nonprofits but mirror treasury transactions in a typical corporate environment. In a broad sense, projecting collections and payables is necessary to determine the timing of each cash flow component, although there may be little control over certain inflows associated with fundraising. Trends and patterns over certain time periods can provide a good basis for arranging financing alternatives during slow months or investing surplus cash longer without risking penalty for early termination of an investment position. Statistical methods of analysis and qualitative techniques may be used in combination to arrive at a reasonable cash forecast.

Estimating the amount and timing of various receipts and disbursements can be time consuming. However, with coordination from various units that have an input to the process, a reasonable forecast can bridge gaps and improve financial planning. Management and marketing/public relations issues must be considered along with payment policies on early-payment discounts and costs that may be unnecessarily incurred due to overdrafts.

| Receipts | Disbursements |

| Lockbox collections | Vendor (supplier) payments |

| Deposits | Payroll, benefits |

| Loans/credit lines | Programmatic expenses |

| Pledge payments | Grants and allocations |

| Debt proceeds | Debt repayments and interest expense |

| Maturing investments | Insurance payments |

| Income from investments | Distributions for planned gifts |

| Endowment fund distributions | New investments |

| Stock gift proceeds |

11.8 SHORT-TERM BORROWING

External financing is an alternative source of funds when no surplus cash is available to meet working capital shortfalls. To account for both short- and long-term financing needs, it is necessary to have a complete picture of the sources and uses of funds, linked to both operational and strategic plans of the organization. Major capital and program expenditures would require a different type of financing, and, typically, loans have to be collateralized.

For liquidity purposes, a bank credit line may be sufficient to fill temporary or seasonal financing needs. This credit line is generally an unsecured loan made on the basis of the borrower's financial strength. The cost to borrow varies and is usually negotiated or reconfirmed annually. Most credit lines carry a variable interest rate based on an agreed base rate. Depending on the perceived risk and the negotiating position of the organization, the interest rate may include a specified spread over the base rate. Interest payments are frequently made monthly or at the maturity of the loan.

Banks usually require compensation for offering a credit line in the form of balances and/or fees. The interest rate on a loan may be negotiated depending on the level of balances held at the bank. Likewise, other activities in the relationship and the overall profitability of the nonprofit's account will affect pricing.

In addition to a bank line of credit, deferring payment on disbursements can be a temporary source of liquidity applying to vendors and other suppliers. However, deferred payments should not be pursued without taking into account the cost of missed discounts in the terms of sale. Implicit costs associated with loss of goodwill and damaged credit rating and explicit costs such as interest charged on late payments should not be overlooked; we strongly advise against delaying payments beyond terms without discussing this first with the party you owe. In certain situations, internal financing may also be an option. For example, borrowing against an endowment portfolio may be possible on an arm's-length basis. For such transactions, careful attention must be given to the terms and conditions of the loan to avoid any potential conflict of interest. For more on short-term financing, see our extended presentation in Chapter 10.

11.9 SHORT-TERM INVESTING

Chapter 12 discusses strategies and instruments for short-term investing. This section addresses some basic considerations. When surplus cash is available, it can be managed to meet liquidity needs or invested. The first step is to determine whether funds are cash reserves solely for operating purposes or available over a longer time frame. Understanding this would enable the cash manager to develop an appropriate strategy to maximize earnings and satisfy liquidity requirements.

With funds managed in a fiduciary capacity, the cash manager's foremost investment objective is safety of principal. Many investment instruments are available, and it is important to understand the market and the types of securities that are bought and sold. Whatever the reason for short-term investing, specific policies and guidelines should be defined prior to making any investment. Investment policies and guidelines should state investment objectives, define tolerance for risk, address liquidity factors, identify the level of return or yield acceptable for different instruments, and identify personnel roles and responsibilities regarding the implementation and monitoring of an investment program. Poor investment judgment, assumption of imprudent risks, assignment of responsibilities to unqualified personnel, and fraud can lead to opportunity costs and loss of principal.

From a cash management perspective, these suggestions are offered:

- Provide copies of investment guidelines to your banker, money manager, or broker with whom you will trade; this will be a good basis for developing appropriate investment strategies and identifying suitable financial instruments.

- Arrange for safekeeping of securities; this offers added security and control and facilitates the audit of securities held. If safekeeping is maintained with the relationship bank, include cost of service in bank account analysis.

- In the absence of a custody or safekeeping account, document instructions for transfer of funds and designate specific accounts for payment of trade proceeds.

- Institute proper operational procedures and controls for investment activities.

- Provide a list of authorized personnel and their specimen signatures.

- Review all portfolio holdings for compliance with credit quality ratings.

- Determine the value of portfolio holding and marked-to-market securities.

- Assimilate investment activities into funds-flow forecasts to manage liquidity.

In addition to these general recommendations, we have some specific recommendations. Consider this question: What can the organization do once it has the cash in position to invest (assuming it has paid down short-term borrowings)?

First, are you sure you are best served with a “free checking” account? You should be able to do better. Like consumers, nonprofits are eligible for negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts that pay interest. The interest rate paid on these accounts may be negligible, however, and must be compared to the fees charged by the bank for its banking services. As the organization becomes larger and begins to consistently hold five-digit balances in the account, it is time to be manually moving some of that to savings or money market accounts. For organizations with $60,000 or more in liquid funds, consider automatic sweep accounts, in which monies above a set dollar amount are automatically “swept out” of the account at the close of business and into an interest-earning investment; these funds are then returned to the account the next day to cover disbursements. (We present more information on sweep accounts in the next section.)

If yours is a larger organization having slightly more risk tolerance for some or all of your excess funds, there are “enhanced return” accounts that invest money actively in a menu of options. More will be said about this in Chapter 12.

(a) BANK SWEEP ACCOUNTS/INVESTMENT SERVICES. One way you might handle short-term investing is through sweep accounts. It is natural for banks, the location in which your surplus funds build up, to offer fee-based investment services. Banks offer their own securities as well as serve as brokers for other institutions' securities. The bank offers investors its own instruments, or those of its parent holding company, as a means of purchasing funds that the bank can loan out or invest. In addition to offering investment securities, many banks offer corporate agency services to safeguard the company's investments, manage trusts and pensions, and handle record keeping related to bonds your organization has issued.

Popular investments your organization can buy through a bank include repurchase agreements (often as part of a sweep agreement), commercial paper, certificates of deposit, Eurodollar time deposits, and Treasury bills. We will discuss only repurchase agreements and sweep accounts here.

A repurchase agreement, or “repo” as it is often called, involves the bank selling the investor a portfolio of securities, then agreeing to buy the securities back (repurchase) at an agreed-on future date. The securities act as collateral for the investor, to protect against the possibility that the bank will default on the repurchase. The difference between the selling price and the repurchase price constitutes the interest.

Quite often, banks will set up a sweep arrangement to automate the repurchase decision-making process, sparing the treasurer daily investment evaluations. All balances above those necessary to compensate the bank for services or to fund disbursements are swept nightly into repos or another safe instrument. The bank may also impose a $1,000 minimum sweep amount to eliminate small-dollar transfers. Transfers are accomplished by a set of bookkeeping entries at the bank. Excess balances are invested for one business day, with the principal amount credited to the checking account the following day. An investment report is produced daily, indicating the amount of the daily investment, the interest rate, the amount of interest earned, and what investment security stands behind (is collateralizing) the investment. As an added advantage of such arrangements, some banks will not charge the company for an overdraft if the sum of the available balance and the repurchased amounts is sufficient to cover presentments, choosing instead to cover the checks with the bank's funds.

You may wonder what interest rate you can receive on such a short-term investment. Exhibit 11.9 shows the rate structures that existed at one point in time for two large Midwestern banks. Bank A calculates its interest rate in this way:

| Bank A | Bank B | |

| Amount Invested | Annualized Interest Rate* (%) | Annualized Interest Rate (%) |

| $0–$999,999 | 4.00 | 4.85 |

| $1–$2 M | 4.25 | 4.90 |

| $2–$5 M | 4.25 | 4.95 |

| $5–$10 M | 4.45 | 5.05 |

| $10 M+ | 4.45 | 5.15 |

* Bank A does not have a minimum transfer amount, and calculates yield using a formula based on the amount invested each day.

Exhibit 11.9 Examples of Interest Earned on Repos

- Up to $1 million, Fed funds rate minus 1.3 percent

- From $1 million to $5 million, Fed funds rate minus 1 percent

- Over $5 million, Fed funds rate minus 0.6 percent

As the bank implements this tiered rate scheme, it pays 0 percent when the Fed funds rate is close to zero, which it was for a number of a number of years post-2008. The message is clear: If you still have a (NOW) account, you are often better off transferring your money into an overnight investment because the yield pickup may be significant. Finally, you will be charged a monthly fee plus a daily transfer fee for the sweep account, and the automated sweep-account fee is slightly higher than a manually operated sweep. These fees must be weighed against the increased interest revenue to determine if your organization would profit from establishing a sweep account.

As an example of a sweep account and two choices that you may have in establishing one, consider KeyBank's product offering (see Exhibit 11.10). Key's sweep accounts include a monthly fee and a fee if the organization either falls below the minimum balance or exceeds the maximum number of monthly free sweep transactions. Furthermore, bear in mind that (1) you will not be able to sweep all the funds you hold in the bank account, as KeyBank requires that a minimum target balance of $25,000 in collected balances be kept in the bank account; (2) if you use the Repo Sweep investment option, your transfers will be made in increments of $2,500 whereas transfers to the Automatic Investment Sweep or Commercial or Public Interest Sweep investments are made in any amount.

Source: https://www.key.com/corporate/kttu/reporting-research/sweeps/sweeps-faq.jsp. Accessed: 7/11/17. Used by permission.

Exhibit 11.10 Three Types of Sweep Accounts

The economics of sweep accounts change as interest rates move up or down. Both Carolyn King (Fifth Third Bank) and Wayne Kissinger (SunTrust Bank) note that a number of their clients' sweep accounts that were inactive were turned back when short-term interest rates rose above 2 percent and continued to rise. The economics are straightforward: Let's say the organization is receiving a negligible interest rate on its checking account and would pay $150 per month to have the sweep service in place. If it can normally sweep $60,000 out on an overnight basis, with interest rates of 3 percent, it is exactly covering that $150 monthly cost ($150 × 12 = $1,800 per year; $1,800 = $60,000 × 0.03); either higher balances or higher sweep investment account interest rates provide an interest income for the organization and make it profitable to use the sweep account.

(b) INSTITUTIONAL MONEY MARKET FUNDS. Many sweeps will move your money into an institutional money-market mutual fund. Or you may choose to invest in a money fund via a separate investment decision, done manually. To give a general frame of reference when assessing whether the yield on your money fund is competitive, compare it to Crane Data's or iMoneyNet's published yields.12 Exhibit 11.11 shows our profile of Crane Data's listing of the highest-yielding large institutional money mutual funds at one point in time.

Source: Adapted from listing provided by Crane Data, “Money Fund Intelligence.” Available at: https://cranedata.com/. Accessed: 1/26/2018. You may also wish to consult iMoneyNet's data, available at the time of this writing at https://financialintelligence.informa.com/about/imoneynet-money-fund-averages.

Exhibit 11.11 High Money Market Yields for Organizations' Short-Term Investments

If you have operations abroad, the availability of bank-provided overnight investing varies considerably. In many cases, you will want to invest foreign cash flows abroad in order to minimize the need to convert to dollars and back to a foreign currency for later needs, which incurs charges for you in transaction costs as well as the risk you bear of the exchange rate changing.

If you are tilted toward safety, you would want to consider the money funds that invest organization's excess cash in governmental (e.g., Treasury) short-term obligations. When drawing the comparison, consider the fund's weighted-average maturity (WAM). The longer the WAM, the more the yield you earn on the fund will lag further upward movements in short-term interest rates (an advantage if rates are moving lower, but a clear disadvantage as rates move higher). Some observers, notably Capital Advisors Group (https://www.capitaladvisors.com/), propose that separately managed accounts might offer a better short-term investment opportunity than institutional money funds in today's regulatory environment.

11.10 BENCHMARKING TREASURY FUNCTIONS

Benchmarking is a process through which an organization compares its internal performance to external standards of excellence. For example, short-term investment performance results are compared by one organization to the Merrill Lynch institutional money fund yield as well as to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), which is the rate at which large banks lend and borrow US dollars in the London market. The objective of benchmarking is to achieve and sustain optimum performance through continual process improvement. Unless an effort is made to clearly understand the nonprofit's mission, operations, staffing, and services provided as well as its customers and other stakeholders, improvement will be slow.

(a) LARGER ORGANIZATIONS. Total quality management (TQM) is a process that has been applied to treasury functions. TQM views quality as adherence to internal standards or guidelines, an approach that fits well with mission-focused nonprofit organizations. Many times it is simply called “continuous improvement.” The four steps involved are: (1) creating a vision and mission statement; (2) understanding suppliers, customers, and the big picture; (3) encouraging cross-functional collaboration; and (4) focusing problem solving on removing root causes in order to produce significant gains. Involving the bank relationship manager and other vendors in assessments will provide valuable feedback to internal staff. Strengths and weaknesses are addressed for various types of processes. The TQM process also relies on quantitative measures and statistical data gathering to evaluate results and monitor process improvement. Through regular reviews and/or audits, fine-tuning can be pursued and changes can be instituted in an organized manner. Nonprofits must approach their business in the same way as for-profit corporations. In so doing, they will be more proactive than reactive, and, ultimately, better efficiency will result in cost savings.

The account analysis statement is a useful source of information for evaluating the quality and cost of various bank services. Transaction volumes can be plotted and analyzed to gauge patterns in lockbox collections, wire transfers, and return items, to name a few examples. Benchmarking can be valuable and should encompass a broad range of activities to provide a meaningful basis for improvement.

(b) SMALLER ORGANIZATIONS. We have developed a checklist for the many nonprofits that are smaller (i.e., $2.5 million in annual revenues or less) so that you can compare your practices and policies to what might be considered best practices (see Exhibit 11.12).

*The principle of saving relevant to many faith traditions is taught in the Old Testament (Proverbs 21:20): “Precious treasure and oil are in a wise man's dwelling, but a foolish man devours it.” The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

Exhibit 11.12 Checklist: Cash and Investment Management Best Practices

11.11 UPGRADING THE CALIBER OF TREASURY PROFESSIONALS

Cash managers of nonprofits must stay abreast of regulatory, service, and product changes. Many major cities have regional treasury associations that provide extensive educational opportunities for practitioners. These typically have as part of their organizational name either “Treasury Management Association” or “Financial Professionals.” Examples are the Kansas City Association for Financial Professionals (http://www.kcafp.org/) and the Association for Financial Professionals of Indiana (http://www.afp-in.org/). Participation in treasury conferences, such as the Association for Financial Professionals' annual conference (see www.afponline.org)13 or other forums on electronic payments (the annual AFP Payments Forum, as well as the annual payments conference of the National Automated Clearing House Association [NACHA] or the five-day Payments Institute; see www.nacha.org) will provide exposure to current and emerging technologies and information. Industry publications, bank newsletters, and technical books are additional sources of information.

Likewise, network with peers from organizations similar to yours as well as corporate and governmental treasury professionals to accelerate learning opportunities and implement changes that can be applied in your treasury department. An enlightened treasury professional is an asset to every nonprofit, and management must invest in staff advancement opportunities.

Cross-training of staff should be supported to ensure continuity in operations. Ongoing training is recommended with backup personnel assigned to critical treasury functions. As advances in technology lead to changes in how tasks are performed, it is advisable to document procedures. A manual should be maintained and updated to reflect any organizational, bank, and system changes that may occur in procedures for initiating wire transfers and ACH transactions. Documentation pertaining to banking resolutions, authorized signatories, and investment guidelines should also be included. Centralized record keeping will ensure continuity and minimize disruptions in operations.

11.12 SECURITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Nonprofit organizations have a fiduciary responsibility for the gifts and donations that constitute a large percentage of their revenues. Recent events associated with fraud, failed investments, rogue brokers, and other financial losses have created concerns beyond risks normally associated with financial instrument quality or creditworthiness. There are various types of financial risk, and a prudent risk management program is relevant not only for treasury functions, but also throughout the entire organization.

(a) TYPES OF FINANCIAL RISK. Here are the significant types of financial risk that may affect your organization:

- Market risk. Risk of change in market price of an underlying instrument, which may be due to adverse movements in currency exchange rates, interest rates, commodity and equity markets, as well as time value of money

- Liquidity risk. Risk associated with investment illiquidity, which can adversely affect pricing of a security

- Credit risk. Risk of counterparty default on an obligation

- Legal risk. Loss exposure due to unenforceable contracts caused by documentation deficiencies

- Funding risk. Risk from internal cash flow deficiencies

- Operational risk. Risk of unexpected loss due to system malfunction, inaccurate accounting and record keeping, settlement failure, human errors, incorrect market valuation, and/or fraud