10

Social Intelligence – The Critical Ingredient to Project Success

Tony Llewellyn

Collaboration Director at ResoLex Ltd, UK

10.1 Introduction

Is construction a technical or a social process? This is a question I frequently ask when lecturing on the subject of building effective teams. The instinctive reaction of the majority of any audience is a clear sense that building is a technical activity. When I then enquire about the skills need to become a successful builder or designer, the responses focus on knowledge of structures, materials, programming, and contracts. There are, however, usually a few more experienced members of the audience who express a different point of view. They have learned that construction is fundamentally about people and the extent to which they are able to connect and communicate with each other. This chapter will focus on the challenge created by a general lack of comprehension of the need for strong social skills, and suggests how the industry might adapt its practice for developing the competences and capabilities of the young, and even not so young people, who work in our industry.

The title of this book is Global Construction Success. The underlying theme of the different contributors is the need to move beyond the technocratic mind set prevalent in our industry and to recognise the risks posed by failing to recognise the essential role humans play in the process of designing and building structures. Developing a new perspective on the process of construction is important for many reasons, not least because so often the root cause of failure in construction projects is not the integrity of the building or structure, but the failure of humans to operate as a cohesive team. Many construction projects suffer from a pattern of behaviours based on a transactional mind set. The common assumption is that all buildings can be designed, priced, and delivered within a defined contractual agreement that requires no attention to building collaborative relationships based on trust. As the project moves outside the contractual parameters and the costs start to increase, the transactional mind set prompts a need to apportion blame, rather than seek to find a win–win solution.

It is easy to see how this limiting mind set evolves. When we first start our training, the focus in the educational system is to learn the science of the numerous elements that go into designing and building a structure. We are taught the technical ‘competences’ in sufficient detail that we can begin a career doing something that is of practical use to our employers. As careers progress it becomes necessary to understand the commercial aspects of the construction process, such as pricing, contracts, and how to manage risk. Sadly this seems to be where most of the learning and development resources applied to the construction industry stop.

10.2 Project Intelligence

Building is a human activity. Generating something new from ‘thin air’ requires groups of people who are able to conceive, plan and then execute a series of complicated activities that will, in some form or other, enhance the lives of other human beings. Large construction projects require the input of many highly specialised skills, which are of limited value themselves but are of significant worth when combined with the skills of others. It is this combination of applied skills that leads to success. Project teams need people intelligence or, more particularly, three distinct types of intelligence.

- Technical intelligence. The knowledge and awareness of how a building or structure is designed and assembled.

- Commercial intelligence. The knowledge and awareness of issues around money, contracts and the identification and management of risk.

- Social intelligence. The knowledge and awareness of how humans behave in groups and teams.

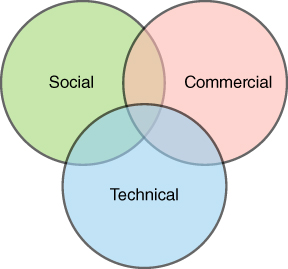

Large projects require lots of people. Despite advances in automation, we remain a long way from having robots to design, manage, and deliver complex engineering software, logistics or construction projects. These enterprises require human expertise and ingenuity to make them happen. As illustrated by the Venn diagram in Figure 10.1, there is a sweet spot where these three elements combine to form the rounded capability to lead and manage a major project. When assembling a project team, we tend to value specialist technical and commercial skills in others because they cover gaps in our own skill or knowledge set. Adding social intelligence to the group, however, tends to be seen as much less important.

Figure 10.1 The three components of project intelligence.

10.3 Social Intelligence

We often use the word ‘dynamics’ to describe how people interact when they are together in a group or team. The word dynamics actually means ‘forces of change’. We tend to use the phrase human dynamics when talking about how people interrelate when they come together as a group or a team. So, human dynamics are essentially the forces that create or destroy the momentum of interaction between groups of individuals.

The problem is that people are messy. Humans are driven by a complex series of emotional reactions that are genetically hardwired into us to thrive and survive. Our behaviours are driven by motivational factors that are often not visible to others and can often be difficult for others to comprehend. To understand others and then have them understand you is an essential human skill. The ability to first understand others and then be understood by them is often referred to as social intelligence. This is a term used to describe a degree of awareness of the human interactions between oneself and others and also between others.

Social intelligence can be defined as ‘the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills’ (Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press). The concept has a variety of possible definitions but at its simplest, it is ‘an ability to get along well with others and to get them to co‐operate with you.’ (https://www.karlalbrecht.com/siprofile/siprofiletheory.htm).

Daniel Goldman (2006) observes that social intelligence has two primary components:

- Social awareness. The ability to sense and understanding the emotions of others. The skills include empathic accuracy, understanding other people's thoughts, feelings and intuitions, and social cognition to recognise the unspoken social norms of a group.

- Social filters. The ability not just to sense but also then act on the information gained. Social facility skills in teams include an ability to present oneself effectively and to influence the outcome of social interactions in the group.

Goldman argues that whilst IQ is something that you are born with, social intelligence is regarded more as a learned skill than it is a genetic trait. This leads us to the question that if social intelligence is an essential component of project success, then why do professional bodies pay so little attention to its development?

My observation is that there tends to be a tacit assumption in many teams that everyone on the team will automatically have the social skills needed to get along well with each other. This often turns out to be a significant misjudgement. Whilst humans have evolved to work in groups, left to our own devices we also have an amazing capacity to find reasons to disagree with and dislike other people or groups. As projects have got bigger and more complex, it is clear that future generations of project leaders are going to have to take the development of their social intelligence more seriously.

Positive social interaction in project teams cannot therefore be left to chance. In just the same way as for technical and commercial competencies, there are methodologies for building strong social bonds. Those methodologies need to first be understood, learned, and then practiced.

We all learn to do it instinctively as we develop from children to adults. This learning is however innate rather than conscious and so it is difficult for most people to articulate. Difficult, however is not the same as impossible. It is quite within our abilities to understand the mental and behavioural patterns of others. However, it does require some knowledge and some effort. As the field of psychology has moved from working with people who are mentally ill to those that are generally mentally well, a large body of information and knowledge has been developed on how we behave in groups. The problem for construction is that in our industry such knowledge has been historically deemed to have little direct relevance to the design and engineering professions.

10.4 Learning and Development

Social intelligence is a learned skill set. Whilst some people have a stronger sense of how to interact socially than others, everyone is able to learn the processes and routines that build communication between adults. As children we typically have few problems engaging with our peers but, as with so many aspects of natural behaviour, we often become more awkward as we grow older.

The prevailing belief in universities and colleges appears to be that the development of social skills should be left to future employers. The problem in deferring the development of these skills is that too much effort is spent on remediating bad habits and rebuilding confidence, rather than providing the more advanced social competences needed to help individuals and teams thrive in a complex environment. It is interesting to note the outcome of a survey of teachers, reported in an article in the Times Literary Supplement dated 30 August 2017. The article highlighted the statistic that 91% of respondents felt that schools should be doing more to help their pupils develop teamwork and communications skills.

There is a tendency to call the ability to understand and communicate a ‘soft’ skill, the implication being that learning how to connect with other people is an imprecise art rather than a precise process. I believe this is an outdated description emanating from a time when managers lacked both the knowledge and the need to recognise the practice and process of efficient and effective team development. The other argument for degrading social skills to the category of ‘soft’ is a belief that they cannot be measured and therefore cannot be managed. This again is simply lazy thinking. There is no difference in my mind in assessing someone's technical, commercial or social capabilities. It is simply a matter of choosing the metrics and then making the effort to collect the data.

Organisations will periodically invest in soft skills training in areas such as presentations, negotiation, time management, and communication.

These are active elements which reflect the ‘tell’ mind set predominant in western organisations. Social intelligence is a wider concept that involves more than just what one person says or does. To be able to influence what happens in a team, you need to understand what is going on. Social intelligence learning includes areas such as:

- Systemic thinking. Seeking to identify all of the different factors that have created a situation. It involves techniques to look at a problem or issue from a number of different perspectives. Rather than reacting to an event by jumping to an immediate conclusion based on your instinctive perception of cause‐and‐effect, systemic thinking encourages you to understand the influence that wider systems will have on a particular situation.

- Understanding group dynamics. Learning how to ‘read the room’ to gauge what is happening underneath the surface behaviours of the team. The skill entails recognising the subtle clues that indicate how people are reacting to each others' nonverbal communication, through body language, tone of voice, and eye movement.

- Influential enquiry. Controlling and steering conversations through the use of skilled questions.

- Conflict management. Managing difficulties and problems by creating an atmosphere that encourages dialogue rather than heated debate.

- Psychometrics. Understanding others by learning to recognise their motivations and preferences and adapting your messages so they recognise your point of view more quickly.

- Sensory awareness. Knowing how to really listen to what others are communicating, not just in words, but also in posture, eye movement, facial expression, and pace of voice.

- Reflection. The habit of methodically taking time to think about recent experiences and consider what happened, why it happened, and what to do the next time a similar situation occurs.

The skills set out above can be taught but as with any skill must be practiced to become proficient. These skills must be learned and developed in the same ways one acquires technical and commercial skills. The initial information can be acquired in the classroom, or from books. The real learning only comes when trying to apply this knowledge in a real life situation.

10.5 Building Cohesive Teams

Projects create a network of interdependencies. Each role relies on several other people to have completed a range of tasks to a certain standard and within a given time frame. When the tasks are clearly understood, the project has the right resources, and the time scales are flexible, then most people can manage to work together comfortably. What happens when conditions are not so benign? One of the predominant features of working life in the twenty‐first century is the high level of uncertainty in the external environment. Technical change and political upheaval create a range of dilemmas for leaders and managers as they try to anticipate the future and react accordingly.

The extent to which a complex project succeeds or fails can therefore be critically dependent on the extent to which the humans involved in the project build the necessary relationships. Few people would argue that teamwork is unnecessary. The reality however is that little resource is allocated to establishing and developing effective collaborative teams. I regularly hear a variety of excuses for this low level of investment, but the most common reason is an underlying belief that provided everyone uses their ‘common sense’ then social connection and collaborative interaction will happen naturally.

There is too much reliance on a one‐off ‘team building’ event after which everyone should be able to ‘get along fine’. The problem is that being friendly is not the same as working effectively. A group of people may find they have a lot in common and meetings are light hearted and enjoyable. That doesn't mean they will now be more able to manage the difficulties of working to tight deadlines and conflicting priorities.

This naïve approach to team development would be understandable if there was no information available upon which to build a knowledge base. There is however a substantial volume of research that has gone into trying to understand the common factors that will take a group of people and turn them into a cohesive unit.

10.6 Introducing a Specialist into Your Team

Training project managers and team leaders to develop their social intelligence skills is not a radical proposition. A more stretching concept is to introduce a specialist in team dynamics into a construction team. Bringing another consultant to sit around an already crowded meeting table might initially seem to add to the ‘noise’, adding further layers of administration and cost. Project managers already complain that clients are often unwilling to pay them to put in the time required to deliver the quality of service that they believe a project needs. The challenge of educating clients to understand value is a topic for another chapter. Here, I want to make the case that adding specialist social skills and capabilities into a project team is likely to demonstrate sufficient value that the costs are irrelevant.

The key to success for most clients is that the project is delivered on time. My research into successful and unsuccessful projects shows that one of the features of having strong social skills in a team is that projects have an increased chance of staying on programme. This is not as tenuous link. Teams who are able to work as a collaborative group tend to engage in dialogue over problems and are able to resolve issues much more quickly than those whose instinct is to resort to contractual debate.

The first part of this chapter has focused on the need for improved social intelligence in a project team. If the skill set is not already present in the key members of the project leadership then it is logical that one should find someone with those skills to add to the team's collective abilities. The proposition is not as radical as it sounds. There are, for example, a number of contracts frequently used in the United Kingdom that require a nominated individual to carry out a role designed to smooth the relationships between the key parties to the contract. The NEC4 Alliancing contract proposes the use of an ‘alliance manager’ whilst the FACI and TAC‐1 contracts published by the Association of Consultant Architects provide for the use of a ‘partnering adviser’. These roles are intended to keep the team focused on maintaining the spirit of the legal agreements to the benefit of all of the parties involved.

10.7 Coaching the Team

A 2017 report by Pinsent Masons titled Collaboration Construction 2: Now or Never? considers the importance of adopting a new set of collaborative working practices to increase efficiency, reduce cost, and improve customer satisfaction. One of the many recommendations of the report is to make use of a team coach. The authors of the report describe the team coach as having an independent role, where the focus is on helping the team achieve the desired project outcomes rather than working with individuals.

The concept of team coaching is rapidly gaining acceptance in many industries and organisations around the world. Team coaching in sporting activities is a well established and recognised role. Many sporting bodies have established codified coaching processes that have then been extended into coaching qualifications. In the business world, the team coaching methodologies and processes are still being developed but many of the executive coaching associations have begun to work out how to structure team coaching, training, and assess competence.

10.8 Managing Behavioural Risk

This chapter has focused on the need for project leaders to pay attention to the social or people based factors in addition to the technical and commercial challenges that every project must deal with. Successful projects almost always feature successful teams where collaborative behavioural norms had been embedded early in the project life cycle. Ineffective teams will always struggle to deliver on their promises and so anyone studying the risk of default must pay attention to the dynamics present within the core team.

In Chapter 19, my codirector Ed Moore and I set out some ideas to set in place the early warning signals of potential team dysfunctions. To close this chapter, however, I would make a final point around the need to expand the team's interpersonal skill set. As mentioned above, the construction industry can repeatedly point to projects where the root cause of under performance can be pinned on a failure of humans to match the behavioural expectations of the team members when the project started.

If you want to ensure such behavioural issues do not derail your next project, will you focus your attention on the technical, the commercial or the social risk?