23

Examples of Successful Projects and how they Managed Risk

Ian Williams MSc, CEng, FICE, FCIArb Stephen Warburton, RIBA and Charles O'Neil

Former Head of Projects for the Government Olympic Executive, London 2012

CEng, FICE, FCIArb

Director, Design & Project Services Ltd

23.1 Introduction

There is no better way to learn how to run a successful project than to participate in one personally. If this is not possible initially then hearing how to do it from highly successful senior managers is the next best way.

In this chapter of the book we are privileged to include the following two papers by Ian Williams, a recognised industry leader of major projects, describing how success was achieved on two of his high profile projects:

- People, People, People. London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games

- Managing Risk. Tunnels for Heathrow's Terminal 5.

These are followed by a really interesting paper by Stephen Warburton:

- Cyber Design Development. Alder Hey Institute in the Park, UK.

Stephen is a highly accomplished design manager with wide international experience.

23.2 People, People, People – London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games

Success for the London 2012 Olympics could be measured in many ways, such as the sell‐out of the tickets; the quality of the sport; the transport operations met all demands; and the security operation ensured no incidents affected the Games. All commentators, without exception, heralded the 2012 London Olympic and Paralympic Games as a great success. Ultimately the summer of spectacular sport and how London performed as a city is what most people remember. However, behind the sport was approximately seven years of preparation covering the construction of Olympic Park and its competition and non‐competition venues. This preparation was the foundation for regeneration of East London, the transport and security operations, the public services and the planning and execution of the Games. The National Audit Office (the independent UK government body scrutinising public spending) stated in their Post Games Review Report that ‘The successful staging of the Olympics has been widely acknowledged’.…and… ‘By any reasonable measure the Games were a success and the big picture is that they delivered value for money’.

This paper covers the factors that led to the success of the activities that were funded by a £9.3 billion public sector package, with the building and commissioning of the Olympic Park and its venues making up about 75% of the budget. These key factors included putting the right governance in place, agreeing a comprehensive and realistic budget, effective procurement measures, effective progress monitoring and risk management and above all, people with the right skills to deliver.

The Olympic Park covered about 250 ha of what would be in legacy a new urban Park, which has about 100 ha of open space and which created one of Europe's largest urban parks for 150 years. Over 200 buildings were demolished and 98% of the demolition materials were used or recycled; using five soil‐washing machines about 80% (1.4 million cubic metres) of contaminated soil was cleaned and reused. The Olympic Park included several permanent and temporary venues; the 80 000 seat Olympic Stadium and warm up track; 17 000 seat Aquatics centre; the Water Polo arena; 6000 seat Velodrome; 12 000 seat Basketball arena; the Hockey arena; 7000 seat Handball arena; Paralympic Tennis centre; the International Broadcasting and Media Centres; and last but not least the 3600 bed Athletes' Village.

Whilst the construction risks in themselves were challenging, the major risk identified at the outset was the ability of government to deliver infrastructure within the allocated budget and to an immovable deadline. In 2005, on the announcement that London was the successful city, the immovable deadline of 26 June 2012 for the opening ceremony was fixed. In 2007, it was identified that the main areas of risk that needed to be addressed were the need for strong governance and delivery structures given the multiplicity of organisations and groups involved; the need for a budget to be clearly determined and managed, applying effective procurement measures; the need for effective progress monitoring and risk management arrangements; and above all people with the right skills to deliver.

At the outset, the government appointed a specialist recruitment consultant to source key individuals with proven major project experience, and expertise in commercial and financial aspects of major projects. A number of key characteristics were sought; a clear understanding of the balance between value and cost, and individuals with a ‘can do’ attitude who were resourceful, who would find solutions and were collaborative in their approach.

In construction terms, achievements on the Olympic Park were extraordinary and had placed the British construction industry at the forefront of delivering major projects. The Park was delivered to schedule and within budget, with the anticipated out‐turn cost of the Park, infrastructure and the Village at £7.2 billion.

London 2012 did not escape the credit crunch. In 2008 the Athletes' Village PFI (PPP) deal collapsed and the government had no alternative option but to fund its construction. However, evidence of the attractiveness of the regeneration and the strong commercial demand for the Olympic assets in legacy mode has since been demonstrated by the deal with Delancey and Qatari Diar for the Athletes Village.

23.2.1 Governance

A single government department was made responsible for the leadership of the public sector funding package, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport through its Government Olympic Executive (GOE). To supplement the team, the GOE recruited a small number of individuals for key roles with a proven track record of experience in delivering major projects. A delivery body, the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) was set up to deliver the infrastructure and venues. ODA was the contracting authority and appointed a delivery partner (CLM) to manage and administer the procurement and the delivery of works contracts. The key for both organisations was ensuring the right skill sets corporately and individually.

Significantly, the GOE was given authority to put in place a governance structure and processes that applied adequate formality to decision making and funding control while maintaining short decision‐making timetables. The forum for key decisions and funding decisions and the release of funding was the Olympic Programme Review Group (OPRG), which was made up of representatives from the government funding and public body funding organisations, chaired by GOE. OPRG reviewed monthly schedule and cost positions and applied clear procedures for release of contingency funds, leading eventually to Ministerial approval. Regular reporting and review ensured that cost management, risk management and management of the limited contingency fund were aligned.

In 2008, the GOE pulled together a comprehensive and realistic budget for the Olympics, which included a contingency element. This budget was articulated in a readily available document, which also outlined the scope, scope ownership and time element for each element of the programme. On agreement of the budget, the GOE was given the authority to manage the release and spending of the budget under the governance of OPRG. This enabled fast decision‐making, acknowledging the immovable deadline of the Olympics. Through its effectiveness, OPRG gained the confidence of government funding departments, which was the key to the decision‐making process. Release of funding for projects was based on submission of business cases. Once approved, the ODA were given authority to manage the budget release and had delegated authority for release of contingency funds.

In response to the governance structure put in place, the ODA applied effective procurement measures to all the projects. They developed a transparent procurement code using the New Engineering Contract V3 (NEC3) standard form of contract. The adoption of the NEC ‘cost‐reimbursed’ form of contract in the main was the key to ensuring flexibility and agility to overcome challenges presented by the project delivery. Acknowledging the disruptive nature of protracted disputes, the procurement code outlined a three‐tier dispute avoidance and resolution process, which involved setting up an Independent Dispute Avoidance Panel (IDAP), a dedicated adjudication panel, with the final tribunal being the Technology and Construction Court.

At the outset effective progress monitoring and risk management arrangements were considered critical tools to manage the Olympics programme. Coupled with the use of ‘cost‐reimbursed’ contracts, transparency of facts was the foundation that supported the governance structure and the timely decision making that was so necessary. This transparency through reporting was also made available to the public on a quarterly basis. This had a powerful effect of demonstrating a ‘no surprise’ approach and the opportunity for public scrutiny from which public confidence in the delivery of the programme was to evolve. Managing risk was put central to the decision‐making process, with regular evaluation and adjustments made to the measures needed to minimise or ideally eliminate risks.

The final and probably key success factor was having people with the right skills to deliver throughout all the organisations. The Government acknowledged that it needed to act and perform as an ‘intelligent’ but lean client organisation. To this end, it recruited individuals from the private sector with a proven track record in delivering major projects. The fundamental shift that also occurred from traditional government procurement was the delegation and authority given to the individuals to ensure delivery to the budget and timescales within the governance process specifically developed for the Olympics.

In summary, the success of Olympic Park and the Games was underpinned by using a purpose‐built delivery model with governance clarity. Central to this was the dedicated GOE team, led by specially recruited staff. The delivery organisations also recruited specialist individuals. For senior roles, acknowledgement of remuneration packages above background levels was necessary to attract the appropriate individuals with the right focus and behaviours. The challenge of an immovable deadline, whilst posing a significant challenge, also presented delivery opportunities which supported the need for timely decision making processes and delegation of authority to the appropriate people at the right levels in the organisations, because these people best understood the risks and the actions needed to manage these risks and to make the right decisions to meet the budget and time challenges. The model adopted allowed the ODA to realise savings and for the GOE to redistribute funds to cover other areas of risk pressures that developed in the operational readiness phase of the Olympics, such as the well‐documented security staff aspects. The approach adopted by the UK Government is a testament to the boldness of the Government in changing its approach, with the result being world‐acclaimed success.

All organisations were aligned to a common goal and the leadership came together regularly to evaluate progress and resolve issues. The common goal fostered a culture that meant there was only one possible outcome – hosting a successful Olympic Games. This ethos resulted in everyone associated with the programme taking personal responsibility and pride in their part in working towards that goal. Flowing from this, were positive attitudes that all issues needed to be resolved in a timely way. This was very evident in the final 12 months of preparation for the Games, when interfaces were at the most crucial, the GOE allocated a substantial element of contingency in order to resolve issues rapidly, coupled with this was specific delegation to a group to administer the budget on behalf of the Minister for the Olympics. This group dealt with up to 30 issues on a weekly basis making sound, but rapid decisions, which resulted in solutions being quickly implemented and excellent working relationships being maintained and even strengthened. This process continued into the operation of the Games and proved effective and contributed to the incident free aspect of the Games.

In conclusion, whilst the government and the supporting organisations set‐up sound, practical governance and processes, the underlying factor was having the right people, with the right behaviours, doing the right thing at the right time. People, people, people!

Source: National Audit Office, The London 2012 Olympic Games and Paralympic Games: Post Games review, HC 794, session 2012–2013, 5 December 2012.

23.3 Managing Risk – Tunnels for Heathrow's Terminal 5 (2001–2005)

23.3.1 Introduction – 1994 Onwards, the Years that Influenced how Terminal 5 would be Delivered

On 21 October 1994, a major collapse associated with tunnelling works occurred on the Heathrow Express project being delivered by BAA (owner of Heathrow airport). Fortunately nobody was killed but the incident resulted in prosecutions. A positive consequence of the collapse was that it was a catalyst for change in behaviour, attitude, and approach within the UK construction industry. The Health and Safety Executive's (HSE) final report (2000) on the collapse stated:

‘those involved in projects with the potential for major accidents should ensure they have in place the culture, commitment, competence and health and safety management systems to secure the effective control of risk and the safe conclusion of the work.’

The scale of the collapse, its impact on the project and the negative impact on BAA's business reputation forced them and their suppliers to address the key lessons from the collapse. The fundamental factor to the recovery solution in 1994 was the adoption of a fully integrated team approach combining risk management with technical innovation.

The collapse also directly affected other contemporary tunnelling projects in London using the same tunnelling techniques. Within 24 hours of the Heathrow collapse, the owner, London Underground Limited, suspended two contracts on the Jubilee Line Extension (JLE) project using the same tunnelling technique. Over the next three months, the JLE project team carried out comprehensive reviews of the technical and management managerial approach of the works and approached the situation from a position of risk mitigation and management. The proposals were submitted to the HSE. After detailed review and evaluation by the HSE the projects were recommenced about three months after the initial stop. This was probably the first time a tunnelling project in the UK had used risk evaluation and management as a tool to evaluate construction decision making.

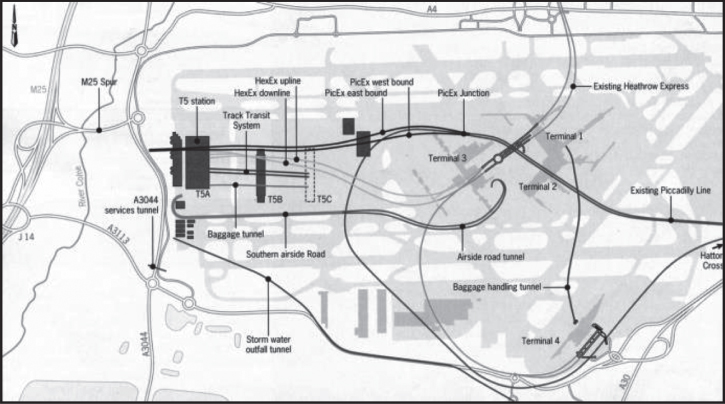

In the early 2000s, BAA embarked on its largest, most ambitious project and also one of the biggest projects in the UK at the time, Heathrow Airport Terminal 5 (T5). The project consisted of a terminal building and two satellites, 60 aircraft stands, car parking for 5000 vehicles, and 14 km of tunnelling to provide road and underground rail links to the terminal (Figures 23.1 and 23.2). The majority of the tunnels were constructed using tunnel boring machines (TBMs) and innovative developments of shotcrete lined method, Lasershell™ used for the construction of the numerous short, complex underground structures, such as shaft and cross passage complexes, (Williams 2008; Williams et al. 2004). T5 was the first major project that BAA was embarking on since the Heathrow Express project in the mid 1990s. Learning from the progressive changes in the approach to British project delivery in the late 1990s flowed out of the Latham and Egan reports and its own learning experiences from the Heathrow Express post collapse project recovery, BAA concluded that in order to meet the challenges to deliver the T5 project safely, on time and within affordability, it needed to develop a procurement and project delivery strategy that was able to meet the challenges of delivering a complex project. BAA accepted that to achieve its objectives, it was necessary to do something different to what was historically done by the construction industry. Taking on its learning from the Heathrow Express post collapse recovery and developments in the industry highlighted in the Latham and Egan reports, BAA considered the key success criteria for the strategy would be a bespoke, non‐adversarial contractual approach based on relationships and behaviours with cost reimbursement as a cornerstone rather than conventional contractual approaches (Wolstenholme et al. 2008). BAA also concluded that all risks could not be eliminated but risk identification and proactive risk mitigation management could decrease the probability of occurrence and reduce the severity of the risk event with robust control processes and mitigation. Furthermore, BAA accepted that the risk of not achieving a successful T5 rested almost totally with BAA, which led to BAA accepting that it owned all the risks all the time.

Figure 23.1 Aerial view of the T5 project (Williams 2008).

Figure 23.2 T5 project and the location of the tunnel projects (Williams 2008).

Unconnected, but running in parallel with the early stage of the T5 project, the insurance industry dealing with insurance for tunnel construction projects noted that disasters associated with tunnelling projects across the world were becoming more frequent, with one of the notable ones in the UK being the collapse on the Heathrow Express project in 1994. Many insurers were considering withdrawal from the market leading to a potentially loss of confidence by client financiers which would have been disastrous for the tunnelling industry. In October 2001, the Association of British Insurers (ABI), representing insurers and re‐insurers from the London‐based insurance market, contacted the British Tunnelling Society (BTS) to share their growing concerns about recent losses associated with tunnelling works both in the UK and overseas. Rather than withdrawing completely from providing insurance cover for tunnelling projects, restricting cover and increasing premiums as a way forward, the ABI sought to work with ‘industry’ to develop a ‘joint code of practice’ for better management of the risks associated with tunnelling works.

In 2003, ‘The Joint Code of Practice for Risk Management of Tunnel Works in the UK’ was launched. The objective of the Code was to promote and secure best practice for the minimising and management of risks associated with the design and construction of ‘Tunnel Works’ (Clause 1.1 of the Code) as well and in the event of a claim, minimising its size. Furthermore, it provided insurers with a better understanding of the risks during the underwriting process and hence increased certainty on financial exposure in the provision of insurance cover. It was acknowledged, however, that strict implementation of and compliance with the Code would not necessarily prevent claims occurring but would reduce their frequency and severity.

BAA concluded that its approach and principles of the Code were aligned.

23.3.2 Terminal 5 (T5) Tunnel Projects – Managing Project Delivery Risks

Central to the success of the T5 tunnelling projects was the approach and strategies adopted to manage the delivery risks. The fundamental aspects were the form of contract (T5 Agreement), assembling the right team with the right values and behaviours, and the approach to risk management, which included the comprehensive adoption of ‘The Joint Code of Practice for Risk Management of Tunnel Works in the UK’.

23.3.3 The T5 Agreement (the Contract)

The T5 Agreement (the contract) was a unique contract because it outlined processes and strategies to manage successful project outcomes in an uncertain environment. It did not outline contractual positions for when things went wrong but focused on principles such as:

- People with the right values and behaviours

- People as individuals working on relationships

- Risk management

- Suppliers working in integrated teams to achieve a common goal

- Suppliers' actual costs were reimbursed with a guaranteed element of profit and an incentive target payment to reward exceptional team performance. In return, BAA expected World Class performance.

The historical consequences of cost and time risks embedded in traditional contracts were not shared, they were held by BAA. BAA owned the risks but expected their suppliers, in integrated teams to manage them.

Underpinning the Agreement were three fundamental working principles considered essential to make the Agreement work; trust, commitment, and teamwork. Emphasis was on selecting key people who had the right values and behaviours and coaching the delivery teams in the values and behaviours.

Figure 23.3 summarises the type of behaviours that characterise these values. For example the project needed people who would do what they say, focusing on outcome not problems, respecting the workforce and selecting people on merit.

Figure 23.3 The right values and behaviours.

23.3.4 Project Delivery Team – Management Approach

Critical to the effective working atmosphere was creating a co‐located single, multi‐company integrated team and forming a project identity that displaced company identities. The division of the team was by function and role not by company. For the tunnelling works the team members consisted of BAA (client and project leadership), Morgan Vinci (tunnel constructors), Mott Macdonald (civil and tunnel designer), and Beton‐Und Moniebau (sprayed concrete lining [SCL] design and on‐site specialist support). The suppliers were selected on merit not on cost.

Specific roles and responsibilities were established and the team members were selected on technical track record and, above all else, the ability to work within an integrated team to achieve common goals. The key team members needed to be able to encourage throughout the team the values and behaviours outlined in Figure 23.3. Selecting the right team, coupled with the T5 Agreement meant that, above all, world‐class engineers co‐located in integrated teams could focus on engineering challenges and finding solutions, not traditional contract management to protect corporate contractual positions.

Apart from the usual project management/administration aspects, the key aspect related to tunnelling risks identified was the responsibilities of the designer and constructor and, critically, the independent role of checking the integrity of the design and the construction operation coupled with ground movement monitoring. The team that undertook this activity was part of the overall integrated team but was independent in function from the construction team. The team had direct accountability and reporting line to the client.

23.3.5 Workforce Safety – Incident and Injury Free Programme

Part way through the T5 programme, the leadership felt that to continue to achieve its objective of zero injuries, the project needed to make a shift in its approach to safety management. Looking to other industry learning, BAA concluded that it had to adopt a behavioural approach to safety management and committed to making this change from the workforce through to the programme leadership. A behavioural safety initiative was introduced, the Incident and Injury Free programme (IIF). The philosophy was getting safety to be personal rather than a routine following of process and procedure. The behaviours of a change in safety culture to influence safety performance were totally aligned to the T5 three values: Commitment, Teamwork and Trust. The implementation of the IIF programme is described by Evans (2008). Many of the suppliers adopted IIF or its principles as part of their company approach and carried through to later projects such as a number of the 2012 London Olympics infrastructure projects

23.3.6 Risk Management

Central to the T5 Agreement was risk management. The strategy of managing risk was through integrating risk and delivery management. The process involved initially exposing the risks through project risk reviews and thereafter regularly updating and reviewing ‘live’ risk registers and ‘live’ risk response plans within the framework of a project execution plan. Notwithstanding the approach to risk management as outlined in UK legislation, the Project Team made an early decision for the rail tunnels to use the guidelines of ‘The Joint Code of Practice for Risk Management of Tunnel Works in the UK’ (ABI and BTS 2003). It was understood that the T5 project was the first in the UK to fully adopt the ‘Code’. Furthermore, by adopting an ‘open door’ policy for the insurer's advisor in the project team activities meant that the insurer was also part of the ‘extended’ integrated team.

On a project working level, IIF and risk management came together, and several innovations and initiatives were developed and implemented for the T5 tunnelling project. Adoption of the cause control measures identified by the risk management process and targeting attitude to personal safety were the two key elements of the strategy used to manage risks related to safety.

The philosophy of the team was to ask questions, bringing in representatives from the delivery team, managers, and workforce to discuss and establish the right approach to eliminate, and if not possible, to manage the risks. This took the form of regular office based workshops focusing on the immediate work activities in hand followed up by on‐site sessions. This meant that the whole delivery team was involved in the solutions not just management as historically done.

23.3.7 The Outcome?

Fourteen kilometres of incident free tunnel construction was completed for the T5 programme without any notable effects on the infrastructures above. This has been documented in numerous publications.

The cornerstone of the success of the T5 tunnelling projects and the wider T5 programme was the contract BAA developed and implemented, the T5 Agreement, and BAA's acceptance that the risks and their consequences rested with BAA. The principles of the T5 Agreement focused on all parties being successful by aligned objectives and using risk management as a tool to support decision making to achieve programme success, enhancing workforce safety and reducing the likelihood and impact of unforeseen events. A fundamental element was the way the T5 Agreement was implemented, this being the three values and behaviours that underpinned the Agreement: Trust, Commitment and Teamwork. Part way through the programme, the IIF safety programme was introduced, which had a massive impact, much wider than just safety, on how the programme was delivered.

Without doubt, the fundamental factor underpinning everything was people. People who embraced the three pillars of the T5 behaviours: Teamwork, Trust and Commitment. Personally, and I am sure others who were also involved with the T5 programme, will look back and conclude that the experience gained was unique and would be a legacy benefit to next projects.

Final thoughts on future projects: many projects have the right contract, commitment to risk management and robust processes, and they have the right people with competence. However, their impact will be limited unless they have the right behaviours and values and can be relied upon consistently to do the right thing.

23.3.8 What Are the Key Lessons Learnt from the Above Projects?

Whilst these two projects are significantly different in terms of scope there are five key elements common to both and perhaps can serve as learning points other projects should consider.

- People. Both programmes realised that having the right people with the right skills was essential to achieve the objectives. People empowered and taking ownership for their actions.

- Client ownership and appropriate procurement processes. The client, BAA for the Terminal 5 programme and the UK Government for the London Olympics, took their role seriously and understood that failure was not an option. This led to how the project delivery was set up and the delivery models adopted, which were customer focused and acknowledged the commercial needs of the supporting organisations.

- Governance and integration. Establishing governance clarity was essential and acknowledging that to achieve the huge challenges, both programmes embraced and promoted the integration of many other organisations and stakeholders working towards an agreed single overall objective, be it a successful Olympics or a world class railway infrastructure.

- Realistic budgets. Budgets established by the people who were responsible for the delivery – ownership.

- Management of risk. Both projects adopted an open dialogue on risk and the challenges ahead, put managing risk central to the project and accepted that ultimately the ownership of the risks lay with the sponsor or client, but the management of the risk was owned by the organisations best placed to manage them.

The rest is history!

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the many individuals from numerous companies and organisations that have been committed to improving the British tunnelling industry over the last 20 years. I would also thank the individuals who were fully committed to the principles of the T5 Agreement of Trust, Commitment and Teamwork, without it none of the successes at T5 would have been achieved. Notwithstanding the commitment of individuals, I also acknowledge the courage of BAA as a client to implement the T5 Agreement and being forthright in demonstrating client best practice and harnessing the lessons of the 1990s. Finally, I would like to thank Terry Mellors (insurer's representative) for his candour and invaluable support during the project and invaluable discussion and contribution of some of the material in preparation of this section.

Ian Williams

Bibliography

- Egan Report. (1998). Rethinking Construction, The Construction Task Force, Chairman Sir John Egan, Rethinking Construction, DETR, London.

- Evans, M. (2008). Heathrow Terminal 5: health and safety leadership. Proceedings of the ICE 161 (5): 16–20.

- The Association of British Insurers & the British Tunnelling Society (2003). A Joint Code of Practice for the Procurement, Design and Construction of Tunnels and Associated Underground Structures in the UK. London: Thomas Telford publishing.

- The collapse of NATM tunnels at Heathrow Airport. A report on the investigation by the Health and Safety Executive into the collapse of New Austrian Tunnelling Method (NATM) tunnels at the Central Terminal Area of Heathrow Airport on 20/21 October 1994. HSE. Books. 2000.

- The Latham Report – Constructing the Team, 1994.

- Williams, O.I. (2008). Heathrow Terminal 5 – Tunnelled underground infrastructure. Proceedings of the ICE 161 (5): 30–37.

- Williams I, Neumann C, Jager J & Falkner L. 2004. Innovative Shotcrete – tunnelling for the new airport terminal, T5, in London. 53rd Geomechanics Colloquy and Austrian Tunnelling Day, Salzburg, Austria, 2004.

- Wolstenholme, A., Ian Fugeman, I., and Hammond, F. (2008). Heathrow Terminal 5: delivery strategy. Proceedings of the ICE 161 (5): 10–15.

23.4 Cyber Design Development – Alder Hey Institute in the Park, UK

A project won by Hopkins Architects in an international design competition in 2013, the £24 million Institute in the Park at Alder Hey Children's Hospital in Liverpool houses around 100 education, research and clinical staff. It is an important building as it is a centre of national excellence for research into children's musculoskeletal diseases and is the UK's only Experimental Arthritis Treatment Centre for Children.

As well as its main sponsors, Alder Hey Children's Hospital and the University of Liverpool, funding for the scheme was from a variety of sources, including the European Regional Development Fund, Liverpool City Council, and The Wolfson Foundation.

My involvement started in March 2014 where the challenge was to submit a tender that hit the brief in terms of cost and programme, whilst focusing on our teams skills to deliver a building of high architectural quality. Many years before, as a trainee architect in London during the summer evenings after work, I would walk across Regents Park and watch a few overs of cricket in the Mound Stand at Lords that Michael Hopkins had designed in 1987. Along with Foster and Rodgers, he had always been one of the ‘greats’ in my eyes.

I made a play on using ‘cyber design development’ or a ‘virtual design workshop’ as part of the tender submission, given the logistics of the wider team based in Bristol, Liverpool, Manchester, and London, and the extensive travel that the design team would have to undertake on a regular basis to meet some tight preconstruction milestone dates. It proved to be unintentionally prescient, as I had imagined all project and design workshops and meetings would naturally take place face to face in Liverpool, but more of this later.

So, after successfully negotiating the tender submission and some tricky interviews our team was announced as preferred bidder in April 2014. Straight away I knew this process would not be a typical run through tried and tested design management procedures, supplier engagement and the obligatory value engineering process in the run up to contract award. No, I was on the train to Woking the next day to visit Hopkin's recently completed World Wildlife Fund headquarters with the project architect. This ‘precedent’ building was immaculately detailed in larch, western red cedar and the best exposed architectural concrete I had seen. This was what we ‘had’ to achieve in Liverpool, no compromises, no short‐cuts, no contractor design, just the architects vision delivered to perfection.

We set to work in May 2014, initially having our design meetings at the architects beautiful modernist offices near Marylebone in London then moving to the site in Liverpool in July 2014 after contract award. All was progressing well, we engaged David Bennett, a world renowned specialist and author of a dozen or so books on architectural concrete to rewrite the engineers' concrete specification and guide us in selecting the very best aggregates and just the right GGBS mixes to achieve our exposed concrete soffits and walls. Various grades of Scandinavian, Canadian, and Scottish western red cedar were investigated before selecting the one that would wrap around the building and fly across the glazing to create a seamless brise‐soleil.

We were slightly ahead of the design delivery programme by the first week in August 2014 when I received a call from one of the partners at Hopkins saying that the project architect had been involved in a serious cycling accident in the middle of London and was having surgery in hospital (he had been hit by a lorry and had his spleen removed, I subsequently found out).

We carried on with the partner architect standing in on his weekly visits to Liverpool, but there was a problem. He hadn't designed the building from scratch, so no rough pencil doodles to basic cardboard model to CAD ‘concept’ model. No intrinsic understanding of how sunlight filtered into the airy public areas and how the laboratories were cocooned within more environmentally moderated areas, or how the bespoke detailing should be resolved to get the best from the quality materials on show. That was all hours and hours of investigation and design optioneering that the project architect had gone through to create a solution or ‘architectural vision’ that the client wanted, but was now lost to the team as a whole.

A month later the impact of delayed design approvals and key areas still ‘in abeyance’ was starting to show, with the piling now complete and the concrete contractor already on site. The project architect was out of hospital by early September but under strict instructions from his doctor not to do more than two days a week in the office, and under no circumstances travel to Liverpool.

I had trialled WebEx earlier that year, so understood its functionality and how it could be used as a video conferencing facility from laptops or a boardroom from pretty much anywhere. Digging a bit deeper, it had various plugins that would allow all meeting participants to see real time drawing markups in Autocad or Revit whilst still seeing ‘windowed’ video and audio. After a few teething problems the system was working perfectly, the engineer in Bristol, architect in London and me in Liverpool flashing up photos or videos in HD of the site works taken sometimes only minutes before. It was a valuable tool, limited sometimes by never being as good as seeing mockups and samples first hand (although these were couriered down to London where possible), but allowing detailed discussion with as much visual material as was necessary to make informed decisions on whether a detail would work, or if it was back to the cyber drawing board.

Almost bizarrely, the WebEx design workshops proved to be better than the real thing due to the focus on a drawing by drawing, detail by detail basis that you naturally have to assume when using this format. No wandering off topic and discussing the performance of the client's project manager or other peripheral issues. It lent a rigour to systematically ticking off all the fine details that we had struggled with up to that point. It made me realise how little we get drawings out on the table these days as a collective design team and collaborate on finding the best solution through negotiating the pros and cons until a general consensus is found.

Many of the well publicised project failures in recent times stem from this lack of detailed investigation and rigorous ‘testing’ at the design stage. At Alder Hey we demanded that all package interfaces were understood explicitly so any risk in subcontractor to subcontractor design coordination had been mitigated well before they arrived on site. Through the WebEx process we could Google and share specific technical data from specialist supplier's websites as we were discussing a problem sitting in different parts of the UK. The sophistication of the major manufacturers' and suppliers' online specification portals is now so advanced that 2D and 3D details are nearly always immediately available, backed up with full specification, warranties, test data, BIM modelling information and environmental accreditation.

In summary:

- Immediate shared access to online specialist design information suits rapid decision making and provides quicker high‐level coordination.

- An online design agenda should be carefully tailored to focus on specific outputs, so less on design team progress, more on visually reviewing and resolving.

- Due to the focus required by online participants, shorter more frequent sessions get better results.

- Any perceived ‘downtime’ by design consultants is easily offset by the lack of any travelling to a live meeting.

- It can be difficult to minute interactive online meetings, so (with the participants consent) WebEx sessions can be recorded and linked to key actions for distribution.

23.5 The Importance of Clear Ownership and Leadership by the Senior Management of the Client and the Contractor

In all development and construction projects the prime objective of both the client and the contractor should be to complete the project with excellence in all the main components of delivery. These are essentially the same for both parties and include:

- A facility that meets or exceeds all the functional and commercial feasibility requirements of the client.

- An aesthetically attractive design that is environmentally compliant and ‘pleasing’.

- Delivery on time, on budget and to the specified quality standards.

- A satisfactory financial result for the contractor, design consultants, suppliers, and subcontractors.

- An unblemished safety record during construction and commissioning.

- Effective risk management processes that provide early warning of potential issues, thus enabling timely action to be taken to forestall or mitigate these issues.

- Managing and resolving conflicts in such a manner that these issues do not turn into formal disputes.

- Excellent working relationships with the relevant authorities and the community.

- Effective communication and relationship management protocols that contribute significantly to the delivery of the above objectives.

If the above objectives are all achieved then the end result will be the delivery of a first class project, but this can only be achieved if there is clear project ownership and leadership evident from both the client and the contractor during all stages of the project. If their performance is first class in these areas then this should flow through to the approval authorities, the design team, and all the suppliers, subcontractors, and stakeholders.

However, if there is a lack of ownership and leadership at senior level then the impact on the project can become quite detrimental to its future viability and operations; stakeholder relationships will be damaged; disputes will occur; and there will possibly be serious financial implications for some or all of the parties to the project.

What then are the key human factors that are required at senior management level of both the client and the contractor in order to ensure that the above deliverables are achieved?

- ‘Project ownership’. This is the passion to deliver a project that all can be proud of; to accept full responsibility for decisions and actions taken and to ‘make it happen’.

- Mutual trust and respect at senior level of the other stakeholders and their objectives.

- Sound decision‐making, taking into account the needs of the project and of the other stakeholders.

- Must be a strong advocate of a collaborative approach.

- Lead from the front with best practice project management, risk management and digital platforms, such as BIM.

- The ability to communicate clearly and unambiguously, including spending personal time with team members and the other stakeholders.

- Natural leadership and people skills that motivate and create team spirit, loyalty, and a strong desire amongst the team to achieve the project objectives.

- Being able to select the right team, having trust in them and delegating responsibility.

- Thorough planning and efficient implementation are essential components of success, and likewise experience, anticipation and the ability to see the bigger picture are essential requirements of a good leader.

- Effective leaders are good delegators and keep some time up their sleeve for strategic thinking, planning, and public relations.

- Sledgehammer managers, yellers‐and‐screamers and bullies might meet the programme and get the job built, but they will never engender team spirit and loyalty or gain the respect of team members or the other stakeholders.

- Successful leaders invariably couple their experience with astute anticipation and effective risk management, and then make full use of good communications and relationship management to resolve issues and keep the project on track.

Some people might say that it is too ambitious and not realistic to strive for and hope to achieve the excellence in delivery that I have described, however I can assure readers that it is entirely possible. I have been proud to participate in a number of projects that have met these goals, including the following quite diverse ones:

- The Mersey Gateway Bridge, UK

- Kelowna and Vernon Hospitals, British Columbia, Canada

- M80 Motorway, Glasgow, Scotland

- Golden Ears Bridge, Vancouver, Canada

- Royal Women's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia

- Somerset Chancellor Court, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- Moree 125 000 t Grain Storage, NSW, Australia

We all understand that it is rarely a perfect world when it comes to delivering infrastructure developments and construction projects and it is quite common to have hiccups with finances, procurement, authority approvals, subcontractors and the like.

However if a project is soundly based in terms of there being a ‘need’ for the facility and the commercial feasibility is viable then these hiccups should be viewed as issues to be resolved in a positive manner.

The difference lies in how you resolve them and this is where clear ownership and leadership on the part of the client and the contractor has great importance. If the senior management of these parties and other stakeholders in the project all have a common objective of delivering excellence then these issues can invariably be overcome and disputes avoided.

Strong leadership will create a project spirit wherein nobody wants to ‘spoil the party’. A perfect project is when outsiders say ‘weren't they lucky to have such a smooth run’ – but it has nothing to do with luck!