But they didn’t fall through space. Realizing that their feet had touched down on something solid, they opened their eyes and saw the last of the colored clouds from Old Cosmos’s portal drifting away to reveal their new destination. They heard a soft click behind them and whirled round, just in time to see the doorway close and then vanish. At the same time they both rose gently off the ground.

They were in the same sort of cylindrical corridor as Ebot had appeared in with his robot escort, but there was no one else around. Had his kidnappers already discovered that he was not actually the great scientist Eric Bellis, however similar they might appear to a computer system or a bunch of robots? Did this mean that they had just stepped into a hostile situation? What awaited them on this strange invisible spaceship?

“We’re floating!” Annie drifted toward the curved walls of the corridor and grabbed on to a piece of pipe. “We’re in space! But I can breathe okay—can’t you?”

“Shush!” said George. “We don’t know if anyone is listening to us.”

“I can’t see anyone.” Annie looked up and down the corridor. At one end there was a door; at the other end it curved away out of sight. “Let’s go this way.” She edged toward the door. “We’ve only got three minutes before they know we’re here.”

“Why that way?” asked George.

“Just a hunch . . .”

“Fair enough. I’ve got your back.” George turned a quick somersault in the air, just as he had seen the robot do through Ebot’s eyes. He suddenly realized something. “How will Cosmos know when to open the portal and let us back? We haven’t got any communication devices with us.”

“And he can only see through Ebot’s eyes!” said Annie, reality dawning on her too. “So we have to find Ebot if we want to get home. Otherwise we’re stuck here. And we’ve got very little time before the time cloak expires; once that happens, the robot army might know we’re here.”

“I hope they have some space provisions,” sighed George, whose tummy was now feeling very empty. “Do we have a plan?”

“Yes,” said Annie. “Find whoever is doing all this stuff and tell them to stop.”

“Or we’ll . . . what—exactly?” asked George.

“Er, don’t know . . . We’ll have to make that bit up as we go along.”

“Great,” muttered George. “That’s just great.”

This was the hardest mission they had ever embarked upon. Previously, they had faced huge challenges and unraveled strange and mysterious events on Earth and in space. But this time they had taken a huge leap into the unknown, with no real idea how to get home, what to do, or what they might find. It was by far the most frightening and bizarre of their adventures; moreover they were peculiarly plan-less. George realized that they were on the edge, cut off from civilization and human knowledge, completely on their own. It was a very odd feeling.

“Better than hanging around on Earth feeling useless,” Annie said firmly, using the pipes along the wall to propel herself toward the door at the end. She floated down and grabbed the handle to steady herself. The door opened immediately, sending her flying backward as something that must have been leaning against the other side of it lurched toward her.

Annie just managed to stop herself from shrieking, while George threw himself forward to protect her from whatever it was. It fell through the doorway in slow motion and floated horizontally for a moment.

“It’s one of those robots!” said Annie. “Nooooo! What are we going to do?” She grabbed hold of George, and they hovered there together, unable to decide whether to stay and face their fate or try to make a quick getaway.

George looked around for an escape route. “Maybe it hasn’t clocked us!” he whispered. “C’mon—let’s try to get away.”

But even as he spoke, the robot floated back upward; for the first time they could see its face clearly. Unlike the ones they had met before, its expression was happy.

“Hello,” it said to them. Its voice was gentle—not what they had expected at all.

“Er, hello,” they both said nervously. Was this I AM? Could I AM in fact be a robot?

George had started to prepare a stern speech about the awful situation on Earth in his head; he intended to deliver it when he finally met I AM, using lots of long words, to impress upon whoever it was that this was very serious and that he, George, was not going to leave the spaceship until he was satisfied that the appropriate actions had been taken. But meeting a friendly, smiling robot with a sugary voice was so surprising that his speech was instantly forgotten.

“What’s your name?” asked the robot.

“I’m Annie. And this is George,” said Annie.

“Would you like to be my friends?”

“Wow,” said George. This really was unexpected. He wouldn’t have flinched if the robot had threatened him and Annie—or tried to arrest or even attack them. But befriending them? That was the weirdest of all.

“Er . . . yes, that would be lovely.” Annie sounded as baffled as George felt.

“What’s your name?” George felt like a little kid trying to make friends on his first day at school. But he didn’t know what else to do.

The robot was now floating straight in front of them so they could see his grinning face. “My name,” he cooed, “is Boltzmann Brian. I am a spontaneously occurring sentient mind, able to replicate an infinite number of times.”

“I thought that was a Boltzmann Brain,” Annie muttered to George.

“There was a spelling mistake when the patent was registered,” replied the robot serenely.

George realized that it must have supersonic hearing. He and Annie would have to be very careful how they communicated with each other. Even though the robot was clearly trying to form a connection with them, George was instinctively reluctant to trust it.

Particles, particles, everywhere . . .

Every material on Earth is made of tiny particles called atoms. These atoms are constantly knocking each other about by exchanging particles of electromagnetic radiation called photons, some of which we feel as heat, others being seen as light, and others we use for communication by deliberately pulsing them out of radio antennas. Photons and subatomic particles produced by the Sun—and coming from more distant parts of the universe—are also constantly flying in from space. So the Earth, other planets, stars, and even space are all swirling soups of tiny particles. How can a scientist possibly understand the behavior of anything when they have to consider such an incredibly large number of microscopic moving parts?

. . . and more than a drop to drink!

Just one quart of water on Earth contains around 30 million million million million molecules! But a quart of water doesn’t look much like a pile of particles—it appears to be a continuous material that can exist as a solid, a liquid, or a gas, depending on the temperature and pressure. Add enough heat, and water will boil and turn into steam; lower the temperature sufficiently, and it will turn into ice. This is normal behavior for water; we can observe it easily. But why should all of these 30 million million million million molecules behave the same way? No rebel molecules?

A nineteenth-century Austrian physicist, Ludwig Boltzmann, provided a mathematical explanation of how the enormous number of particles involved actually makes a particular behavior pattern overwhelmingly the most probable. For although the multitude of particles effectively moves entirely randomly—each one doing its own thing—it is most likely to produce an average overall behavior in which individual molecules can be forgotten. In a quart of water, a small fraction of the molecules may randomly and briefly deviate from this average, but the probability that this fraction would be large enough to produce a noticeable change in what we think of as the normal behavior of water is very, very small.

If the water were to be left alone forever, however, large random fluctuations would eventually take place—for example, all the molecules could find themselves moving for a short time in the same direction. Now this is a very, very, very low probability, so if you leave a quart of water in a jug, you wouldn’t expect to see it suddenly leap out. But if you could leave it for an eternity, such fluctuations would eventually occur—and occur an infinite number of times.

What does this mean for the universe?

The universe began 13.8 billion years ago in a Big Bang, and it is expanding at an ever-increasing rate.

If we apply the same principles to our universe as we just did to water, we can see that a universe that carries on forever would contain every possible random fluctuation, an infinite number of times. This means that a perfect copy of our universe today—after all, it is a perfectly good arrangement of particles—would eventually appear randomly somewhere else in the particle soup.

A copy of our universe would obviously include copies of all our human brains, with all their memories too! But as creating all of that randomly is much, much more difficult than forming just one working brain on its own, it would be more probable that these random fluctuations would create single brains, complete with their memories, much more frequently than whole people or copies of the entire Earth.

A large enough particle soup, with a non-zero temperature and left for eternity, could therefore randomly create all possible brains—Boltzmann Brains—with all possible memories, infinitely many times. So if our universe should last forever, floating in space would be infinitely many Boltzmann Brains—each with all the brain’s memories, right up to the moment when you thought you read this!

Are you sure you aren’t one of them?

“Unfortunately, it was not possible to change it once the patent had gone through,” the robot continued.

“Aw, poor you!” said Annie, not knowing quite what else to say.

“I like your hair,” the robot told her.

“What?” Automatically, she flicked her bangs.

“And you look very intelligent,” said the robot, addressing George.

“Erm, thanks!” he said. Was the robot pre-programmed to give out compliments to random people it met while floating about the spaceship? he wondered. What was the point of creating such an odd machine?

“Time is running out,” Annie whispered right into George’s ear. “We’ve nearly reached our three minutes.”

George nodded very slightly so she knew he had heard her.

“Boltzmann . . . ,” he said politely. “Brian? Did you just say you could replicate an infinite number of times? Is that actually true?”

“I have been specially created to be able to copy my body in a simple and user-friendly fashion,” said the robot rather proudly. “I can send my specifics to a 3-D-enabled printer on Earth and then print out a version of myself.”

“And can you print yourself out anywhere you want?” asked George.

“Anywhere on the planet,” replied Boltzmann.

George felt a prickle of horror as the full implications of this dawned on him. At the touch of a button, he realized, this robot could be re-created by 3-D printers all over Earth, which meant that anyone who wanted to form a robot army there didn’t need to manufacture them or import them. Just give the right command, and however many 3-D printers there were on Earth—and George suspected there might be far more than people realized—would produce a robot that was presumably loyal to its creator. George imagined it must be the quickest way to take over the Earth ever, especially if the place was in a state of chaos and no one even noticed what was going on or tried to stop it until it was too late.

What if all the governments and armies and police forces and security services were distracted by collapsed transport networks, free giveaways from the banks, failing food supplies, grounded aircraft, bursting dams, exploding power stations, and any number of the other recent catastrophes—and didn’t notice a robot army seizing control? Even if it was a nice robot army, determined to compliment people . . .

George suddenly noticed that while they’d been talking, the robot had slowly, almost imperceptibly, been pushing them backward along the corridor.

“So how many of you are there right now?” asked Annie.

“Just the one,” said Boltzmann Brian. “There is only one true Boltzmann Brian.”

“But there are more robots than you on this spaceship?” said George.

“Correct.” Boltzmann continued to usher them backward. “There are many copies of my robot body on this ship—an entire ensemble. But none of them have a brain. They’re very unlikely to get one, you see, even if you cook the head for a long time. . . . I’ll let you in on a secret.” The robot gave a self-satisfied grin. “I’m much nicer than the others.”

“Are there more robots on Earth?” asked George.

“Correct once more!” Boltzmann replied happily. “More units have recently been replicated via 3-D printers in selected locations on Earth.”

“Do you mean the nasty ones?” asked Annie. “The angry robots that keep chasing us around?”

“I have been specially educated to be extremely user- friendly,” said Boltzmann Brian with a glassy smile. “But the others . . .”

Annie and George didn’t need to hear the end of the sentence to understand what it meant.

As it spoke, an alarm blared out and two of the other robots—the ones with the mean faces and vicious pincer grips—appeared behind Annie and George, grabbing them tightly.

“Ow!” cried Annie as a robot latched on to her arm and dragged her toward the end of the corridor.

Held in a viselike grip by another of the menacing robots, George could do nothing to help her. Like Annie, he was swept along the corridor by his robot escort.

Boltzmann Brian followed closely behind, bleating, “Wait for me!”

For a moment George wished they’d been able to stay with just Brian—while that particular brand of nice had been a little creepy, it was a lot better than the threatening faces that surrounded them now. Where were they going? Would they find Ebot once they got there? he wondered.

He and Annie couldn’t see their destination, given that they were traveling backward, until the robots suddenly let go of them and they floated into the most extraordinary room that either of them had ever seen.

What is 3-D printing, how is it different from 2-D printing, and why is it so exciting?

What does “3-D” mean?

The “D” stands for “dimensional,” so something that is 3-D, three-dimensional, is something that has the following dimensions:

1. a length

2. a width

3. a height

So, while a picture on a piece of paper is a two-dimensional image (flat on the paper), physical objects that you interact with every day (like your bike, your dinner, and your nose) are all “three-dimensional.”

Slicing a sausage!

2-D printing (two-dimensional) is what we usually think of when we say “printing”—for example, using a printer connected to a computer at home or in your school or library.

A 2-D printer usually:

• uses special inks to make the 2-D images on paper.

• takes an electronic file that describes a whole 2-D image—like a photograph from a digital camera or a document from a word processor—and then electronically “slices” it up into lots of very thin strips. This process is sometimes called salami-slicing because it’s a bit like a chef chopping a salami into slices!

• takes each electronic slice in turn and carefully squirts colored inks onto a matching section of paper to produce a precise image of that slice.

• then moves down and does the same for the next slice, and then the next, until finally the entire image has been built up on the paper one slice at a time.

• Artists and filmmakers can make 2-D objects appear 3-D by using tricks: like perspective in pictures and 3-D special effects in movies. But these are optical illusions, and the images themselves are 2-D, as they only have a width (first dimension) and a height (second dimension).

When my son was younger, he would watch with fascination as our printer whirred away, producing photographs and letters. He’d also watch carefully if we bought something (like a toy) on the Internet—he would wait expectantly by the printer for whatever we’d just bought to plop out of it! I guess that would make complete sense to a four-year-old. The funny thing is, for some types of toys, this is now close to reality.

Making a real 3-D object

In 3-D printing, what is made is not just a 2-D image but a real 3-D object. The machines that do this are called 3-D printers or Additive Manufacturing Machines.

It begins, like 2-D printing, with an electronic file. However this is now a special type of electronic file called a CAD model (“CAD” stands for “computer-aided design”) that describes every single detail about the object to be 3-D-printed.

If you look at the CAD model of an object on a computer screen, you can see an image of what the object looks like from the outside, but you can also “fly through” to see what the object looks like from any point inside it.

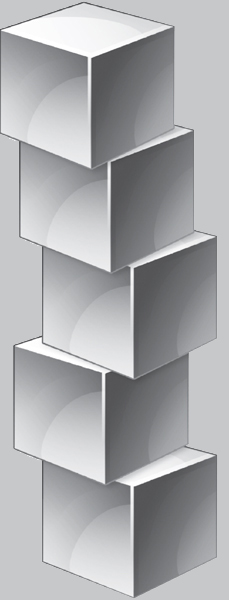

The 3-D printer salami-slices the CAD model into electronic slices, one on top of another, where each slice might be about 20 microns thick.

Although all of the slices are 3-D because they have thickness (or length) as well as width and height, the 3-D printer treats each slice as a 2-dimensional cross section showing precisely what the object would look like if it were carefully cut through.

The 3-D printer prints out each slice—starting with the lowest—just like a printer would a 2-D image. But instead of squirting ink onto paper, it produces all the details in each slice as a 20-microns-thick layer of “stuff.”

The material for one slice dries and hardens, then the 3-D printer indexes (moves up) and produces the next slice as another 20-microns-thick layer on top of the previous one.

This process is repeated over and over until all the slices of the CAD model have been printed one on top of another to produce a real 3-D object!

20 microns—or 1/50th of a millimeter—is approximately 25% of the thickness of one of the hairs on your head! A CAD model of an object that is 10 cm (4 in.) high would therefore be salami-sliced into about 5,000 electronic slices!

• The most common material used is plastic, as it can be easily squirted out in very small amounts as a liquid and will quickly harden into a solid. It is also ideal for making prototypes (models of new things like buildings or cars). As modern machines can use several different kinds of plastic at the same time and can print in color, prototypes can be very realistic. This is still the biggest application for 3-D printers.

• There are two common types of 3-D printers used today:

Extrusion Machines: the material is forced through a nozzle, rather like using a piping bag to ice a cake. These machines are especially good when using more than one type of color of material, since more nozzles can easily be added.

Bed Machines: these are most commonly used with powdered metals. Enough powder is poured out to completely fill one slice, then a power laser fuses (melts and joins) the powdered metal into a solid shape at precisely the right places in the slice. Once the model is complete, the excess powered metal is brushed away.

• Over the next few years scientists expect that machines using plastic will become more common in peoples’ homes, allowing you to download patterns and 3-D-print things like made-to-measure bike helmets or fun personalized toys. Imagine printing yourself as a Star Trek or Harry Potter figure!

• 3-D printers in factories use materials like metals and ceramics—for example, to print out parts for jet airplanes that are lighter and stronger, thereby making the airplanes safer and more fuel-efficient.

• Medical devices like implants for new hips and teeth, and cranial plates (used to repair holes in heads), can also be 3-D-printed, because this process allows them to be made specifically for the person they will be fitted into.

Robots of the future?

Today’s 3-D printers are still quite slow and can only make things out of a few different materials at the same time—it would not yet be possible to print a complete robot since you would need complicated interlocking parts made of many materials: metal parts, gears and motors, magnets, wires, plastics, oil, grease, silicon, gold—even weird things like yttrium and tungsten!

But 3-D printers could easily make parts for robots within a fully automated factory. The parts could then be unloaded from the 3-D-printers by unloading robots, polished by polishing robots, and then assembled by assembly robots . . .

Robots using 3-D printers (with other technology too) to make robots? Is this something you will see in the future?

It was as if they were in a spherical, clear glass bubble, floating through space. At regular points around the perimeter, openings led into more corridors: these tubes curved away from the central room to an outer circle, like the spokes of a bicycle wheel.

Apart from these, the room was completely transparent. When they looked down, they saw that even the floor (or was it the ceiling? It was hard to know in space) was made of the same glasslike material.

It was the most amazing thing George had ever seen; for a second it took his breath away. He had dreamed of diving through space; now, he realized, he was probably as close to this as he could ever get—suspended in a glass bauble with an awesome view of the universe on all sides.

But when George gazed out, it wasn’t just the emptiness of space or the dark sky peppered with stars that grabbed his attention. It was something far more beautiful: a jewel-like blue-green planet, clothed in a thin wispy veil of atmosphere. It was their home.

“It’s the Earth!” breathed George as he and Annie drifted around the room. A lump came into his throat. He reflected that it would be difficult to explain this feeling to someone who had never flown in space. When you left the Earth and then looked back and saw it—fragile, ancient, mysterious, and enchanting, suspended against the blackness of space—it made your heart burst with protective, homesick feelings. You wanted to stay in space forever, but you also wanted to rush home and look after your beautiful planet, hanging there so courageously in the vast emptiness.