The city that Hitler had never planned to capture, and that Stalin had never intended to defend, lay sweltering under the summer sun. No rain had fallen for two months and, day after day, the temperature soared well above one hundred degrees. Worse, the humidity that typifies a river town was totally enervating. When the wind blew, it always came from the west—hot, dusty, bringing no relief. The citizens of Stalingrad were accustomed to being uncomfortable and they joked about how the heat made the concrete sidewalks bulge and buckle upward, splitting the slabs into giant fragments. As for the shiny asphalt roads, all one could do was watch the mirages rising from the wide boulevards in the center of town.

Few people in this cauldron knew their city was about to become a battlefield, but the tragedy of war had always menaced the region. In the year 1237, the Golden Horde of the Great Khan had crossed the Volga at this perfect fording point, ravaged the territory, galloped on to the Don, and then swept westward into European Russia, stopping their invasion just short of Vienna and the Polish border. During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Moscow began her own expansion into Asia; the region became a border post from which Russian soldiers sallied forth to fight the Mongols. When the czar decreed the area safe for settlement in 1589, he established a trading center called Tsaritsyn. In Tartar language the name was pronounced “sarry-soo” and meant “yellow water.”

Though the location was safe enough to settle, it never knew peace. Russian brigands wreaked havoc on the citizenry as they plundered their way north and south along the length of the Volga. The geographical key to bringing the wealth of the Caucasus to Moscow and Leningrad, the heartland of Russia, as well as being the east-west gateway to Asia, Tsaritsyn was a place for which men would always do battle.

The legendary cossack leader, Stenka Razin, took the city in 1670 and held it during a bloody siege. Just over one hundred years later, another cossack named Yemelyan Pugachev, decided to challenge the power of Catherine the Great and stormed Tsaritsyn in an effort to free the serfs. The rebellion ended as could be expected. The czarina’s executioner cut off Pugachev’s head.

Still the city prospered, finally taking its place in the industrial revolution when, in 1875, a French company built the region’s first steel mill. Within a few years, the city’s population had grown to more than one hundred thousand and, during World War I, nearly one-quarter of the inhabitants were working in its factories. Despite the boom, the city reminded visitors of America’s wild west. Clusters of tents and ramshackle houses sprawled aimlessly along the riverbank; more than four hundred saloons and brothels catered to a boisterous clientele. Oxen and camels shared the unpaved streets with sleek horse-drawn carriages. Cholera epidemics scourged the population regularly as the result of mountains of garbage and sewage that collected in convenient gullies.

It was almost predictable then that the Bolshevik Revolution would bring Tsaritsyn to its knees. The fighting for control of the region was unusually bitter and Joseph Stalin, leading only a tiny force, managed to hold off three generals of the White Army. Finally driven from the city, Stalin regrouped his forces in the safety of the steppe country, fell on the flanks of the White Army in 1920, and won a pivotal victory in the revolution. To honor their liberator, a jubilant citizenry renamed the city Stalingrad, but words alone could not repair the damage wrought by war. The factories had been rendered useless, famine struck down tens of thousands, and Moscow decided the only way to save the area was to return it to its industrial state. It was a wise decision. The new industrial plants soon were exporting tractors, guns, textiles, lumber, and chemicals to all parts of the Soviet Union. During the next twenty years, the city grew by leaps and bounds along the high cliffs of the western bank of the Volga. Now half a million people called it home.

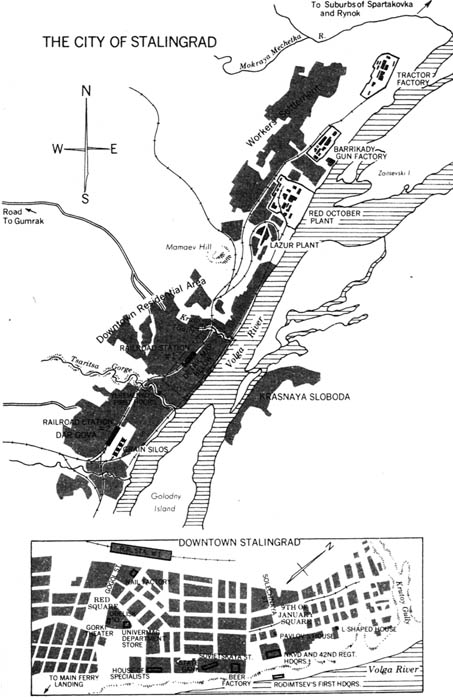

When General Yeremenko first looked down on Stalingrad through the window of the plane bringing him to battle, he thrilled at the sight. Hugging the serpentine bends of the Volga, the city looked like a giant caterpillar, sixteen miles long and filled with smokestacks belching forth clouds of soot that told of its value to the Soviet war effort. White buildings sparkled in dazzling sunlight. There were orchards, broad boulevards, spacious public parks. During the drive from the airport through the city, Yeremenko felt himself overwhelmed by the power and charm of the rawboned metropolis.

The general’s underground command post was located in the city’s heart, only five hundred yards away from the western shore of the Volga in the north wall of a two hundred-foot deep, dried-up riverbed called Tsaritsa Gorge. A superb location for a headquarters (some said that it had been built years before on explicit orders from Premier Stalin himself), the bunker had two entrances: one at the bottom of the gorge and the other at the very top, leading into Pushkinskaya Street. Each entrance was protected from bomb blasts by heavy doors, plus a series of staggered reinforced partitions, or baffles. The interior was lavish by Russian military standards. The walls were paneled with an oaken-plywood surface; there was even a flush toilet.

In his comfortable office, Yeremenko immediately began to familiarize himself with his domain. On the desk lay a huge contour map, marked in pencil to show the demarcation line between his Southeast Front and the Stalingrad Front to the north, commanded by Gen. A. V. Gordov. The boundary ran straight as an arrow from the town of Kalach, forty miles west at the Don River, to the same Tsaritsa Gorge where Yeremenko sat. The longer he examined the artificial border, the more he fumed at STAVKA’s inability to realize that the dual-front concept was absurd. Worse, he had already spoken with General Gordov and discovered him to be as insufferable as he was reported to be. In the best of times a difficult man, under pressure Gordov became a tyrant, humiliating his staff, inciting open revolt among subordinates. Now faced with Yeremenko, a rival for power, he was evasive, uncooperative, and unpleasant. But since there was no point waiting for STAVKA to admit its mistake and reassign command responsibilities, Yeremenko tried to come to grips with his own immediate assignment.

He lingered over the map, searching its symbols for clues to a defensive strategy. Between Kalach and Stalingrad there was only steppe country—flat, grassy terrain that was perfect for German panzers. He next eliminated the assorted farms in the region, the kholkozi, where he knew thousands of Stalingrad’s citizens were finishing the job of snatching a bumper wheat harvest from the invaders. The farm crews out there had been straining under the brutal sun while Stuka dive-bombers machine-gunned them and set fire to trains filled with grain. Nevertheless, nearly twenty-seven thousand fully loaded freight cars had already rolled away to safety in the east. Behind them came nine thousand tractors, threshers, and combines along with two million head of cattle, bawling plaintively as they pounded toward the Volga and a swim to the safety of the far shore.

The “harvest victory” was the only one that Yeremenko could savor. Four rings of antitank ditches being dug twenty to thirty miles west of Stalingrad offered little hope. Neither did the “green belt,” a twenty-nine-mile arc of trees planted years before to ward off the effects of dust clouds and snowstorms. Only a mile wide at its thickest point, it could not withstand the concentrated fire of heavy artillery.

Yeremenko’s attention wandered southward, down the map to the rail center of Kotelnikovo, seventy-three miles away. Captured by the Germans on August 2, the city controlled the main road to Stalingrad. The German line of march was obvious: through Chileko, where the Siberian 208th Division had just been decimated by the Luftwaffe, and on to the towns of Krugliakov and Abganerovo. At the latter location, Yeremenko paid closer attention to swirling lines on the contour map indicating hills rising to elevations of from two to three hundred feet. The hills followed the main road the rest of the way to the congested suburbs of Stalingrad. With mounting excitement, he noted deep ravines cutting across the region from east to west and concluded that it would have to be in this twenty-mile strip of hill country that he would try to halt the German advance.

Deep in his heart, however, Yeremenko knew that eventually he would have to fight for Stalingrad block by block and street by street. So, as he pored over the map, he embarked on a peculiar mental exercise: replacing the map’s impersonal symbols with his own images of rock formations, houses, and streets, he strove to understand the battleground he had inherited. The southern part of Stalingrad became a jumble of white wooden homes, surrounded by picket fences and flower gardens. This was Dar Gova, a residential zone just below some light industrial development that crowded close to the Volga—a sugar plant and a massive concrete grain elevator that looked like a gray dreadnought on a prairie sea.

A short distance north of the elevator, the Tsaritsa Gorge cut its two hundred-foot deep scar in the earth before it ran due west for several miles into the steppe. Just above this dividing line was Gordov’s territory, over which Yeremenko had no jurisdiction. But he kept on with his studies, because he intended to be ready when STAVKA came to its senses.

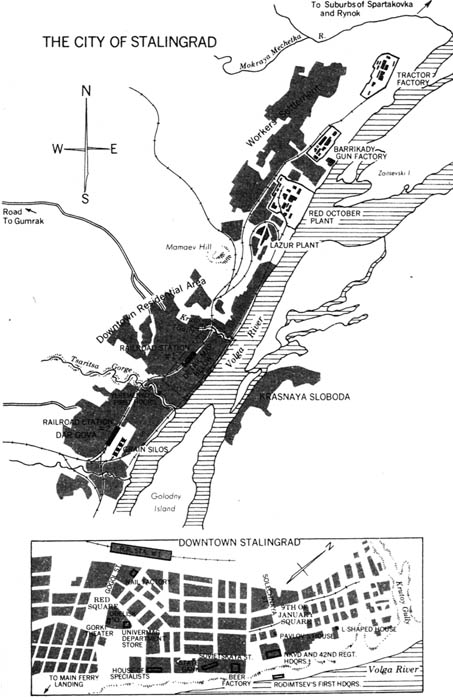

Here was the heart of the city. It encompassed more than one hundred blocks of offices, stores, apartment buildings, and was bounded on the east by the central ferry landing—the only major crossing point on the Volga—plus a promenade along the Volga shore. To the north, it was cut off from the next section of the city by another deep ravine, the Krutoy Gully, and on its western flank was another drab community of single-storey frame houses. Yeremenko sensed immediately that this whole central section of the city could become a fearsome line of defense. Reduced to rubble by gunfire, the fallen bricks and mortar would provide perfect cover for Russian infantry.

The center of town also contained Railroad Station Number One. For months trains had passed through it carrying refugees from other battlegrounds: Leningrad, Odessa, Kharkov. Crammed into cattle cars, when the trains stopped in Stalingrad they jumped off to find water and barter for food with merchants lining the platforms. While they haggled for fruit and bread, the penniless among them stole whatever they could behind the vendors’ backs. But in early August, the motley traffic from other fronts had to share train space with thousands of Stalingrad natives who suddenly had been ordered eastward into Asia by official decree. Now the terminal was swollen to the bursting point with tearful relatives embracing children, old men, and women, amid choked promises to write and keep well. The shrill whistles of the locomotives finally separated the groups. With a last wave and forced smile, a new flood of refugees joined the trek into the vast interior of Russia.

A half block east of the station, the men responsible for the city’s evacuation occupied a five-storey office building on the west side of the shrub-lined Red Square. Across the square, beside the cavernous post office, the newspaper Stalingrad Pravda (“Truth”) still printed a daily edition and distributed it to an anxious readership. Under the guidance of the chairman of the City Soviet, Dmitri M. Pigalev, and other members of the council, it published information about air raid drills, rationing, as well as battle reports from the front. To ward off panic, it reported only that the Red Army was scoring impressive victories west of the Don.

Close by, the squat, ugly bulk of the Univermag department store guarded the northeast corner of the square. Once a showroom for fashions from sophisticated Moscow, its counters now held only essential items: underwear, socks, trousers, shirts, coats, and boots. In the Univermag’s gloomy basement warehouse, reserve stocks had sunk to an alarmingly low level.

At the south side of the square, the Corinthian-columned Gorki Theater still hosted a philharmonic orchestra that played regularly in an ornate auditorium festooned with graceful crystal chandeliers hovering over a thousand velvet-backed seats. The theater represented the pinnacle of perfection for Stalingrad’s citizens who resented the city’s reputation as a provincial pretender to culture.

North of Red Square, soldiers clucked horse carts along wide boulevards, past row after row of sterile, white brick apartment houses that looked like barracks. Automobile traffic was minimal and exclusively military in nature. In the evenings, the streets would be filled with pedestrians strolling beneath maple and chestnut trees lining the sidewalks. Many strollers whistled tunes from Rose Marie, which had played for weeks at a downtown theater.

Occasionally, a public garden separated the housing complexes. On Sovietskaya Street, a bank interrupted the residential pattern. A flour mill intruded along Pensenskaya Street. Closer to the Volga, in a library facing the river, a prim matron handed out copies of books by Jack London, a favorite author of the young people.

Neighborhood stores tucked into corner lots competed for business. “Auerbach the Tailor” offered soldiers in ragged uniforms a dingy shop in which quick repairs could be made. Swarms of flies pestered women as they picked over watermelon and tomatoes at open-air markets. Beauty parlors were crowded with girls on off-duty time from war work at the factories.

In the Tsaritsa Gorge, Andrei Yeremenko had already scanned the intersection at Solechnaya Street to assess its military significance. He also examined labyrinthine side roads, off the Ninth of January Square. What really fascinated him was that immediately to the north of Krutoy Gully, the buildings abruptly gave way to a grassy, rock-studded slope rising to a height of 336 feet. This was Mamaev Hill, once a Tartar burying ground and now a picnic area. From there, a casual observer could see most of the city. The view was breathtaking. To the west, there was an uninhabited stretch of steppe country, badly broken by balkas (deep, dried-up riverbeds) and, on the distant horizon, a line of homes and a few church steeples. To the north was the awesome network of industrial plants that had made Stalingrad a symbol of progress within the Communist system. Almost at the base of Mamaev were the yellow brick walls of the Lazur Chemical Plant. They covered most of a city block and were girdled by a rail loop resembling a tennis racquet. From the Lazur, trains puffed north past an oil-tank farm on the bluff beside the river, then on to the Red October Plant with its maze of foundries and calibration shops, from which poured small arms and metal parts. Further north, the trains passed the chimneys and towering concrete ramparts of the Barrikady Gun Factory, whose outbuildings ran back almost a quarter mile to the Volga bank. There a row of workers’ homes languished in an unfinished state. Around the yards of the Barrikady, hundreds of heavy-caliber gun barrels lay stacked, awaiting shipment to artillery units at the front. Beyond the Barrikady loomed the pride of Russian industry, the Dzerhezinsky Tractor Works. Once the assembly point for thousands of farm machines, since the war it was one of the principal producers of T-34 tanks for the Red Army.

Built in eleven months, the tractor factory had opened officially on May 1, 1931, and, when it was completed, it ran for more than a mile along the main north-south road. Its internal network of railroad tracks measured almost ten miles; many workshops had glass roofs to permit a maximum use of sunlight. Ventilation ducts, cafeterias, and showers had been added to the plant to make the workers’ lives more pleasant and productive.

On the other side of the main road, paralleling the eleven miles of industrial park, a special, self-contained innercity had sprung up to accommodate families of factory employees. More than three hundred dwellings, some six-stories high, housed thousands of workers. Clustered around carefully manicured communal parks, they were only a few minutes’ walk from summer theaters, the cinema, a circus, soccer fields, their own stores and schools. Few factory personnel living in this compound ever wanted to leave it. The state had provided almost every basic necessity and the model community that Stalin had fostered was a showpiece of the Soviet system.

From his mental perch on Mamaev, Andrei Yeremenko was not unduly concerned about the view north into the “economic heart” of Stalingrad. Even the most powerful field glasses of an artillery observer, should he chance to be a German, would not be able to penetrate as far as the tractor works, or past it to the uppermost boundary of Stalingrad, the Mokraya Mechetka River.

What alarmed Yeremenko about Mamaev was its staggering vista to the east—down the shimmering Volga, which was jammed daily with hundreds of tugs, barges, and steamers, whistling at each other in riverboat language and trailing wreaths of smoke as they navigated the channels between barren Golodny and Sarpinsky islands. The route they traveled, a vital artery of the Soviet war machine and necessary to any intended defense of Stalingrad, was completely exposed to the whims of the army that possessed the hill. Furthermore, the far shore, which was as flat as a billiard table and stretched into infinity, lay open to observation; so was its lush meadowland, once an amusement park for vacationers who went there to dance or to swim at the pearl-white beaches and to spend weekends at the cottage village near the shore. Now the meadowland was deserted. But through it, in time of need, must come the soldiers, ammunition and food for the relief of Stalingrad. And from Mamaev, an enemy could easily track every boat that left it.

Finished with his exercise, Yeremenko wearily pushed his map away and began issuing orders. Now, more than before, he was determined to dig in firmly along the line of hills that began near Abganerovo. Proper antitank defenses there should delay the German advance. But first he had to scrape up enough manpower for the job.

Above his bunker, a flaming red sun had set; the night air was uncomfortable and muggy. Civilians walked down to the relative cool of the river embankment, where a crowd of evacuees waited for a ferry to arrive from the opposite bank. In a waiting room beside the ferry pier, men and women filled pots of boiling water from giant copper kettles. Some used the water to wash clothing, others to make “tea” from dried apricots or raspberries. It was all they had left.