“Manstein is coming, Manstein is coming,” the shouts went along the frozen balkas in the Kessel between the Don and Volga. Soldiers cheered his name and repeated stories of his genius to each other: Manstein, whose plan to outflank the Maginot Line had led to the fall of France within six weeks; Manstein, who reduced the Crimean fortress city of Sevastopol within days. Listening to these stories, the men of the Sixth Army gloated over the coming of the hook-nosed, silver-haired legend and laughed at their temporary status of “mice in a mousetrap.”

General Seydlitz-Kurzbach did not laugh at the army’s predicament. Thoroughly cowed by Hitler’s order to bear co-responsibility for defense of the pocket, he decided to avoid any blame in case the Sixth Army perished. He began writing.

FROM: Commanding General 51st Army Corps |

November 25, 1942 morning |

To: Commander in Chief of the Sixth Army [Paulus] I am in receipt of the army command of November 24, 1942 for the continuation of fighting.…

The Army is confronted with a clear alternative: breakthrough to the southwest in general direction of Kotelnikovo, or the annihilation of the Army within a few days.… The ammunition supplies have decreased considerably. The assumed action of the enemy, for whom a victory in a classic battle of annihilation is in store, is easy to assess.… One cannot doubt that he will continue his attacks … with undiminished vehemence.

The order of the High Command … to hold the hedgehog position until help is near, is obviously based on unreal foundations.… The breakthrough must be initiated and carried through immediately.

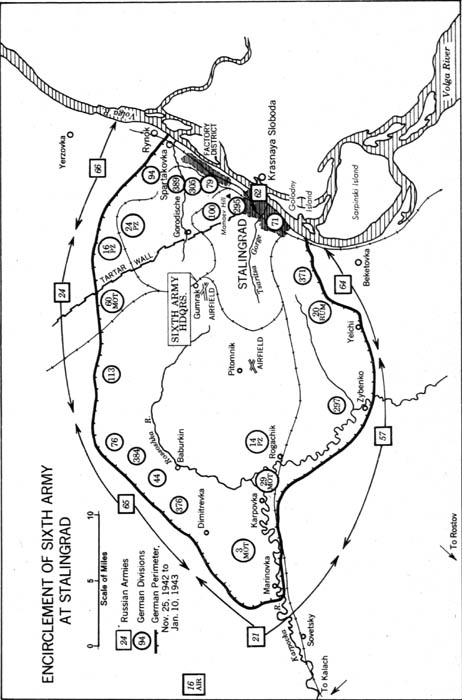

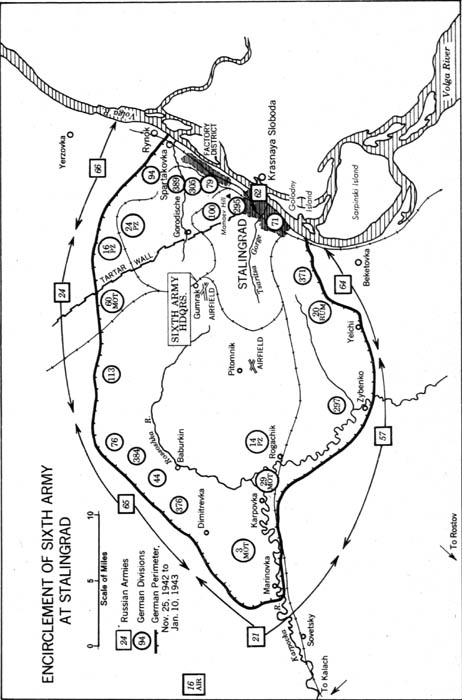

Paulus read Seydlitz-Kurzbach’s comments with the tolerance a father might show a wayward son. He needed no such analysis from Seydlitz-Kurzbach. For days he had known that retreat from the Volga was imperative. In the precious hours that had been lost, at least sixty Soviet formations were now encamped on the perimeter of the Kessel, their guns trained on Sixth Army. To the south and west, at least eighty other Red Army units were ready to repulse any German attempt to fight through to Paulus. By November 25, the Germans inside the Kessel were twenty-five miles away from the nearest friendly troops.

At the air bases closest to Stalingrad, German airmen struggled to make the airlift succeed. Gen. Martin Fiebig directed the piecemeal buildup from Tatsinskaya and Morosovskaya, which had been excellent fighter and bomber bases during balmy summer months, when weather permitted hundreds of sorties each day. But now it was wintertime, and the air units on the steppe faced enormous difficulties. Three-motored Ju-52s, transport workhorses of the Luftwaffe, flew in from distant bases. Some were old and untrustworthy; others lacked guns and radios. Crews ranged from veterans to green graduates of training schools in Germany. Many fliers came to Russia in regular-issue clothing, without any garments suited for below-zero temperatures.

On November 25, the first planes had lifted off for Pitomnik Airfield inside the Kessel. For two days they struggled in and out, carrying fuel and ammunition. On the third day, November 27, the weather closed down all operations and Fiebig added up the sorry totals. In the first forty-eight hours, only 130 tons had been delivered instead of the required 600. Sadly, he wrote in his diary: “Weather atrocious. We are trying to fly, but it’s impossible. Here at Tatsinskaya one snowstorm succeeds another. Situation desperate.”

Marshal Richthofen agreed wholeheartedly. Despairing of the airlift, he telephoned Kurt Zeitzler and Albert Jeschonnek to warn them that Sixth Army had to fight its way out before it lost its strength to move. Richthofen begged them to submit his opinion to Hitler. They did, but Hitler refused to be swayed. He told Zeitzler the Sixth Army could hold out, must hold out. If it left Stalingrad, Hitler declared, “we’ll never get it back again.”

When Richthofen heard this verdict, he decided that he and other commanders were “nothing more than highly paid NCOs!” Though completely disgusted, the frustrated Luftwaffe general kept his temper in check and went back to work. His rationale was simple: “Orders are orders.”

Meanwhile, the Russian High Command wrestled with its own serious problems: the success of the vast encirclement. Neither Stalin nor Vasilevsky or Zhukov had dared anticipate the dimensions of their triumph. Prepared to deal with up to one hundred thousand of the enemy, they suddenly realized that nearly three hundred thousand armed soldiers had to be contained and liquidated.

In Red Army staff schools, such an operation had never been broached. Only Zhukov had practical experience in dealing with a surrounded enemy; at Khalkin Gol in Manchuria in 1939, he had successfully eliminated a portion of the Japanese Kwantung Army in a period of eleven days. But that force had totaled only one fourth of Paulus’s Sixth Army, now at bay, dangerous and defiant.

On November 28, Stalin called Zhukov to discuss the complex difficulties of dealing with the Stalingrad “fortress.” Once again, the premier needed his deputy’s calm analysis of an emergency. Zhukov answered with a telegram the next morning:

The trapped German forces are not likely to try to break out without help from a relief force.…

The German command will evidently attempt to hold its positions at Stalingrad.… It will mass a relief force for a thrust to form a corridor to supply and eventually evacuate the trapped forces.…

The trapped Stalingrad group should be cut in half.…

But the Russians had no quick formula to achieve this goal. By now, seven Soviet armies were hugging the Sixth Army in a hostile embrace. The Sixty-sixth and Twenty-fourth pressed from the north; the Twenty-first and and Sixty-fifth barred exit to the west; the Fifty-seventh and Sixty-fourth pushed up from the south. In Stalingrad itself, Vassili Chuikov’s Sixty-second Army held the Volga shoreline as it had since September.

The Kessel was roughly thirty miles wide by twenty miles long, its western side tapered so that it resembled the snout of a giant anteater. In its middle, five corps headquarters dotted the steppe around Paulus while on the perimeter, weary divisions faced outward.

Manning the northern front closest to the Volga were the 24th and 16th Panzer divisions. To their left, stood the depleted 60th Motorized and 113th Infantry. In the northwestern sector, the nearly destroyed 76th, 384th, and 44th divisions licked assorted wounds from their retreat across the Don. At the extreme western edge, in the “snout,” the remnants of the 376th Division held a precarious foothold beside the 3rd Motorized. On the south side of the pocket, the 29th Motorized Division braced anxiously next to the 297th and 371st divisions. The 14th Panzer and 9th Flak divisions roamed the pocket in reserve, moving from position to position depending on the threat.

Two Rumanian divisions and one regiment of Croatians fleshed out the southern line closest to Stalingrad. And in the city, six exhausted battle groups held all but five percent of the town. There, the 71st, 295th, 100th, 79th, 305th, and 389th divisions clung to the same cellars and trenches they had occupied during September and October.

At the edge of the Volga, General Chuikov stormed in and out of his cliffside bunker cursing his bad luck. His war had become static—a backwash to the drama on the steppes to the west and south—and the Volga continued to plague him. Pack ice drifted by in enormous chunks, grating against each other like knives scraping glass.

On November 27, the disgusted Chuikov radioed front headquarters across the river: “The channel of the Volga to the east of Golodny and Sarpinski islands has been completely blocked by dense ice.… No ammunition has been delivered and no wounded evacuated.”

The offensive on the steppe had not solved all his problems. Not only that, but he smarted under a directive that put his troops on short rations. Chuikov was furious with his superiors and he told them, “… with every soldier wanting with all his heart and soul to broaden the bridgehead so as to breathe more freely, such economies seemed unjustified cruelty!”

The Germans were already on half rations. Caught with most of its supplies on the wrong side of the Don, where the Russian offensive had swept the steppe, the Sixth Army had only six days’ full rations for each man when the encirclement began. But Karl Binder had done his job well. The quartermaster’s foresight in moving his food, clothing, and cattle east, out of the danger zone made his 305th Division one of the few “rich” ones. Then Paulus ordered an accounting of available supplies, insisting on a “balancing” of provisions among the units.

Binder was outraged. He had little sympathy for those who had failed to anticipate the calamity. Nevertheless he gave up part of his reserves: three hundred head of cattle, eighty sacks of flour, butter, honey, canned meat, sausage, clothing to destitute neighbors. Binder felt his labors for his own troops had been in vain.

Veterinarian Herbert Rentsch had a different problem. His horses, Russian panjes and Belgian drafts, were going to the butchers to sustain the army. The doctor was glad he had not sent four hundred animals back to the Ukraine just before the pocket closed.

He also had a personal crisis. His own horse, Lore, was showing the effects of inadequate grazing. Her rib cage showed through her winter coat. No one had yet forced him to include Lore in the list of horses to be killed, and he refused to think about that possibility.

At the western edge of the pocket, the last German regiments and companies ran across the bridges over the Don and passed through the rear guard holding the Russians in check. The last German soldier to cross the Don toward Stalingrad was a first lieutenant named Mutius. During the early morning of November 29, he looked back at the dark steppe. At 3:20 A.M., he pushed down a plunger and the bridge at Lutschinski burst into an orange ball of flame that lit the shore on both sides, illuminating a long line of German vehicles moving east, into the Kessel.

On November 30, forty He-111 bombers joined the Ju-52 transports on the run to Stalingrad. It took fifty minutes to cross the snowfields of the steppe and follow the radio beacon to the landing strip at Pitomnik, which was a beehive of activity. Mechanics swarmed over the planes as soon as they landed, unloading equipment swiftly, even siphoning off extra gas from wing tanks to replenish the fuel of the armored vehicles inside the pocket. On that day, almost a hundred tons of vital supplies arrived. Paulus was encouraged to believe that the Luftwaffe was about to meet his demands. It was not. Another weather front moved in and for the next two days, hardly a plane made it to Pitomnik.

Since the beginning of General Yeremenko’s offensive, Lt. Hersch Gurewicz had stayed in place on the right shoulder of the breakthrough, the sector closest to the city. When Soviet armies probed the southern perimeter of the Kessel on December 2, he jumped into an observation plane and took off to scout the terrain.

Beneath Gurewicz, the German lines appeared as dark smudges, irregular scars. While marking the data on his map, a sudden burst of antiaircraft fire shook the aircraft, which spun wildly out of control. Gurewicz braced himself in his cramped seat and the pilot managed to pull out of the dive only to crash-land extremely hard. A tremendous explosion smashed Gurewicz unconscious. Hours later, he woke to find the cabin a shambles and the pilot dead. Gurewicz looked down at his pants, soaked through with blood. His right leg throbbed; it was bent almost at a 45-degree angle to his body.

He worked feverishly to get out of the plane, but the pilot’s body kept falling over on him and Gurewicz felt a surge of panic. Finally he threw his weight against the door and fell out into a snowdrift. His leg hung by one piece of skin above the knee; he dragged it after him with his right hand. His mind fully alert, he suddenly realized that the explosion which ripped the plane apart was a mine, and that he was alone in no-man’s-land, in a minefield.

He crawled very carefully, looking nervously for any telltale traces of explosives planted in the snow. When twilight came, he could not see clearly, and his breath froze in the cold wind. The leg tormented him but the freezing temperature congealed the blood around the wound, keeping him from bleeding to death.

Gurewicz struggled on. His face was caked with snow and ice had formed over his eyes and lips. By now it was completely dark, and the lieutenant lost his nerve. Afraid to move among the mines, he lay forlornly in the snowfield, shivering miserably, the pain from his wound making him want to vomit.

Somewhere in the darkness, a light wavered and Gurewicz heard men talking in low tones. The light grew stronger, hands suddenly reached out and pulled at him. When he heard musical Russian phrases, his joy at being saved released pent-up emotions. For the first time in the war, tears flooded down his face. He cried uncontrollably as his countrymen tenderly lifted him onto a stretcher.

That night, doctors cut off his right leg almost at the hip. They told him his war was over, that he would need a year to recover. Thus he went back across the Volga one last time, while behind him, the Red Army tightened its grip on the Germans in the Stalingrad pocket.

Sgt. Albert Pflüger knew it was just a matter of time before the Russians came across the sloping hills. At an outpost of the 297th Division just south of Stalingrad, he had monitored the buildup of tanks and artillery for several days. But his company was powerless to prevent it. They were running out of ammunition.

The dawn was gorgeous, a violent red sun which poked over the horizon beyond the Volga. Russian shells followed immediately and the rolling barrage drove Pflüger and his men into the ground. When the barrage lifted to pass on to the rear, Pflüger raised his head to see black Soviet T-34s approaching through a smoke screen. Three of them cautiously worked down a hillside. The first disappeared into a gully.

Pflüger waited patiently to spring a trap. He had stationed a .75-millimeter antitank gun to his right, out in no-man’s-land. When the first tank crawled up from the gully, the sergeant fired a purple Very light into the sky and the .75 roared. The shell cut through the tank turret and passed on into open air before it exploded. Two Russian soldiers tumbled out of the T-34 and raced madly back up the hill. Pflüger was tracking one through his sights when he suddenly thought, My God, if you’ve been that lucky, who am I to shoot you now. He lowered his rifle and let the man go.

The other tanks came on. The .75-millimeter gun fired again and the second vehicle took a shell in the turret, which catapulted fifty feet in the air before crashing back down on the tank. The third T-34 was hit in the undercarriage and spun crazily for a moment before coming to a stop.

The sergeant had won the first skirmish. But the Russians regrouped. As Katyusha rockets sang over his head, Pflüger called for artillery support. He got only seven rounds from rear batteries which were being severely rationed.

The tanks appeared again and Pflüger’s .75 went back into action. After the gun fired fifteen rounds, Pflüger received a phone call from his irate commander who screamed, “Only take sure shots.” And, in the middle of the battle, the sergeant had to explain why he had been so reckless with ammunition. He was told to get his crew on the ball.

For his work in driving off yet another enemy attack, Pflüger received an official reprimand for wasting shells.

On December 4, the Russians attacked the Kessel from the north and northwest. The 44th Division took the main blow and the fire brigade, the 14th Panzer Division, rushed to help. Fighting swirled around foggy Hill Number 124.5 and one German regiment lost more than five hundred men. Hundreds more suffered frostbite in the frigid temperatures. Sgt. Hubert Wirkner helped take back one position that had been held by Austrian troops until the Russians ran over them with tanks. He found the defenders where they had fallen. All lay naked in the snow. All had been shot.

On the northern side of the Kessel, forward observer Gottlieb Slotta of the 113th Division talked quietly to Norman Stefan, an old friend from Chemnitz in eastern Germany. For several weeks Slotta and Stefan had shared their food, shelter, and innermost thoughts. Both men believed that Hitler would not leave them on the Russian steppe. When they talked of the past, Slotta often confided his reactions to the trauma he experienced in September when friends had ignored his warnings and died from shell-bursts. The memory still haunted him.

Each day he trained his binoculars on the growing numbers of Red Army units deploying in front of him. Each day he phoned this ominous evidence back to headquarters. It was a hopeless gesture. The 113th Division had barely enough ammunition to hold off one concerted attack.

Stefan was always beside him, observing the same buildup. Frequently he stood at full height and walked back and forth in the trench. Slotta joked with him about it, warning that an enemy sniper would find him irresistible.

Finally a Russian noticed Stefan, tracked his path along the the line and, as Slotta turned to give another warning, a rifle cracked. Stefan crumpled to the bottom of the shelter. That night Slotta went to the aid station and waited beside his friend for some time. But Stefan died without saying another word.

On the eastern side of the Kessel, at the Barrikady plant in Stalingrad, Maj. Eugen Rettenmaier was faced with a renewed tempo in the fighting.

The commissar’s house and houses 78 and 83 erupted as Red Army soldiers infiltrated them at night and fought for control of the wrecked buildings. Grenades exploded in brief flashes in the pitch-black rooms. In the morning, half-naked bodies littered the stairwells and cellars.

Major Rettenmaier sent his officers in piecemeal to hold these battered houses behind the Barrikady. They generally lasted for three days before they, too, were wounded or dead.

His reinforcements, mostly young soldiers from Austria, were used up by the end of November. House 83 had become a crucible, where most of the Germans who went in never came out again. For two days, men fought for just one room. Thick smoke billowed from it. Grenades killed friend and foe alike.

When a sergeant stumbled back to Rettenmaier’s command post and demanded more grenades, a doctor looked at his bloodshot eyes and told him: “You must stay here. You may go blind.” The sergeant refused to listen. “The others back there can hardly see a thing, but we must have grenades.” Only when another soldier volunteered to take them did he slump into a chair and pass out from exhaustion.

Rettenmaier finally had to abandon House 83. But at the commissar’s house, his troopers from the Swabian Alps held on with their characteristic “pigheadedness.”

Rettenmaier also was facing an acute decline in morale. The half-rations his men ate did not alleviate their melancholy, and they missed their homeland most of all. Deprived of regular mail, they fell victim to forebodings of an inconceivable fate. Conversations dwindled to whispers in the shelters. Men sat on their bunks for hours, seeking solitude with their thoughts. They wrote letters at a feverish pace, hoping that airlift planes might carry their innermost sentiments to relatives waiting at home.

When a trickle of mail arrived at the Barrikady from Germany, the lucky few read them over and over, caressing the paper, sniffing any scent.

Cpl. Franz Deifel had returned from leave in Stuttgart two weeks earlier and each day he hoped his certificate of release from the army would arrive so he could get out of the Kessel and go back to work at the Porsche factory. In the meantime, he drove an ammunition truck each day to an observation post on the rear slope of Mamaev Hill. It was a boring job, made lively now and then by indiscriminate Russian shelling, so Diefel made a game of it, guessing which section of the road the enemy planned to hit. So far he had been right in his predictions.

Finally, he received a summons to regimental headquarters and ran to the bunker where a clerk handed him a slip of paper: “Here’s your release.”

Deifel read it slowly, and the clerk shook his head, muttering, “Damn rotten luck!” It had come too late: Only the wounded and priority cases could now leave Stalingrad.

One of the priority cases who climbed into a bomber at Pitomnik was the recipient of a premature Christmas present.

Dr. Ottmar Kohler was astounded when the staff of the 60th Motorized Division insisted he go home to see his family. Grateful for his devotion, they had rewarded the combative surgeon with ten days’ leave in Germany.

When he refused the offer, he received a direct order from superiors to make the trip. Stunned by such solicitude, Kohler said his good-byes to men who had no chance of seeing their loved ones in the near future, if ever again, and promised to come back on time.

The homeland Kohler visited was uneasy because the German people had finally learned some of the truth about Stalingrad. When the Soviet Union issued a special announcement about their victory on November 23, it forced Hitler to allow some information to go out in a communique from the Army High Command. No mention was made of an encirclement, only that the Russians had broken through northwest and south of Sixth Army. The communique attributed this alarming fact to Russia’s “… irresponsible deployment of men and material.”

Because of the vagueness of the news, fear gripped the German civilian population, especially those people with relatives on the eastern front. Frau Kaethe Metzger was one of them. More and more concerned because she had not heard from Emil, she phoned the local postmaster and asked: “Is 15693 among the Stalingrad Army postal numbers?”

Though forbidden to give out such information, the man, an old friend, answered, “Just a minute.”

Kaethe’s heart pounded while she waited. The voice came back on the line. “Do you mean to say Emil’s there?”

She could not answer.

“Hello, Kaethe, hello!”

Her eyes filled with tears, she hung up and stared blankly out the window.

Army Group Don headquarters at Novocherkassk was a gloomy place. Nothing was working as it should, and Hitler continued to “put spokes in the wheels” of Manstein’s expedition to Stalingrad.

The 17th Panzer Division had failed to arrive because Hitler pulled it off trains to act as reserve for an expected Russian attack far to the west of Stalingrad. And east of Novocherkassk, the 16th Motorized Divsion stayed in place because Hitler feared another attack from that direction.

In addition, the Red Army launched a series of spoiling operations against Colonel Wenck’s impromptu army, now renamed Combat Group Hollidt. This mini-offensive, known as Little Saturn, was designed to blunt the one-two punch Manstein was readying as part of Operation Wintergewitter (“Winter Storm”), the establishing of a corridor to the Sixth Army.

In Moscow, STAVKA was reading Manstein’s mind through the Lucy spy ring in Switzerland. Thus, Zhukov and Vasilevsky had mounted Little Saturn as a stopgap measure, which delayed temporarily their more grandiose scheme, Big Saturn, the destruction of the Italian Army and the Germans in the Caucasus.

For his part, Manstein could not wait much longer to make his move. A delay of only a few days might prove fatal to Sixth Army’s slim chances, so he speeded up the timetable and put his faith in the tanks assembled around Kotelnikovo. At least the 6th and 23rd Panzer divisions were ready to roll.

In spite of the encirclement, the discipline and organization of Sixth Army remained excellent. On the road network, military police directed heavy traffic and routed stragglers to lost units. The highways were always well plowed. Road signs pointed the way to divisional, corps, and regimental headquarters. Fuel and food depots handled rationed supplies in an organized, crisply efficient manner. Hospitals functioned with a minimum of confusion, despite the increasing number of casualties, approximating fifteen hundred a day. Drugs and bandages were reasonably plentiful.

At Pitomnik Airport, wounded men went out on the Ju-52s and He-111s at a rate of two hundred a day. They left in good order, under the watchful eyes of doctors who prevented malingerers from catching a ride to freedom.

Given the gravity of the situation, Sixth Army was functioning better than some might have expected. But certain signs of decay were becoming evident. On December 9, two soldiers simply fell down and died. They were the first victims of starvation.

By December 11, Paulus knew his superiors had failed him. During the first seventeen days of the airlift, a daily average of only 84.4 tons arrived at Pitomnik, less than twenty percent of what he needed to keep his men alive. Paulus was seething with frustration and when Gen. Martin Fiebig, the director of the Luftwaffe air supply, flew into the pocket to explain his difficulties, the normally polite Paulus heaped abuse on him and excoriated the German High Command.

A genuinely sympathetic Fiebig let him rant, as Paulus told him the airlift was a complete failure. He referred constantly to the promises of adequate supplies and the brutal truth that barely one-sixth that amount had actually arrived:

“With that,” Paulus lamented, “my army can neither exist nor fight.”

He had only one flickering hope, which he indirectly referred to as he wrote his wife, Coca, “At the moment, I’ve got a really difficult problem on my hands, but I hope to solve it soon. Then I shall be able to write more frequently.…”

Paulus knew that Manstein was about to keep his promise, at least, to try to save the Sixth Army.