THE MAIN REASON I got to work in the Potala was having a friend to introduce me, as just explained, but it was also because an ordinance had been issued by the Chinese government for the preservation of what remained of Tibet’s destroyed cultural heritage. Apart from those piled up in heaps and crammed into some scrap-metal storerooms near Ramo-ché in north Lhasa, most of Tibet’s looted precious metal statues had been transported to China, where they were melted down and used to manufacture bullets and many other things, and since the Cultural Relics Office now had orders to prevent the remainder from being used in the same way, they sent a group of young workers sorting scriptures at the Potala to go and pick out those worth saving. Since they were in need of more workers to help with this task, I was recruited into that temporarily, and then went on to join the group sorting out the books.

The broken statues we had to go through were graded by quality, and the great majority of those made of the finest materials, like bronze, had been taken to China, although a few survived, such as the upper half of the Jowo Aksobhya-vajra of Ramo-ché, which was later recovered in China. In the storeroom where I was working, there were mostly fragments of massive gilt-copper statues, but also many small bronzes that we picked out, and the least damaged of those were placed in the upper-story apartment of the Késang Po-trang palace in the Norbu Lingka. We came across copper utensils such as kettles, braziers, cooking vessels, and so on, right down to chamber pots, which had once belonged to ordinary Tibetan households, jumbled up with the debris of statues and offering vessels deliberately smashed during the Cultural Revolution, when these things were condemned as “spirit monster” paraphernalia. Household objects had been looted and destroyed as much as possible in China during the Cultural Revolution, just as they had been in Tibet, and it struck me that this showed how they had eliminated all traces of the fact that Tibetan household implements were totally different from those in use among the Chinese.

After we had finished sorting through the statues, I went on to reassembling and cataloguing scriptures in the Potala. After a few months, those workers who were more religiously minded, single, and childless were taken onto the staff of caretakers at the palace, and I was one of those put in charge of sweeping up and maintaining the Dalai Lama’s apartments, temples, and reception halls. This was an enviable position, and for me, it meant the chance to start living a meaningful life. Initially, the older and newer sweepers worked together on keeping these rooms tidy and receiving visitors, but soon after, when the palace was first opened to the public, the newly appointed sweepers were each put in charge of a chapel. We assumed the duties of a sacristan, keeping the chapel in order and receiving those who came for worship, something more significant than being just a caretaker, in which I exerted myself with joy and devotion.

During my time in the Potala, there was an incident where one of the statues in the meditation chamber of King Songtsen Gampo went missing. The statue in question had been given by the king of Nepal to one of the TAR leaders, Tien Bao, when he went to Nepal on a “friendship” tour. It was made of rather ordinary gilt copper and was not at all ancient, but was considered valuable because of its significance to bilateral relations. As soon as the loss was discovered, the palace officials got very flustered and reported it immediately, as required by the Cultural Relics Office regulations. The customs officials at the Nepal border were informed and started rigorously searching anyone leaving the country, while Cultural Relics officials were sent to the palace to investigate. At the time the statue had disappeared, the caretakers were still working as a group, so there was no individual to be held responsible, and we newer employees were still arriving, so most of us had no idea which statue it was, how big it was, or what it was made of. All the same, we newly appointed caretakers were summoned to a group meeting with the Cultural Relics official Rikdzin Dorjé and told to give our views about how the statue had been taken, who might have done it, and whether we thought it was a Chinese or a Tibetan. Since this question was political, no one said anything. The statue was said to have been one [Khru = approx. 19.5 in.] in height, and at that time visitors carrying large bags were required to leave them at the entrance in the Déyang-shar courtyard. It would hardly have been possible for someone wearing a chuba [Tibetan gown] to carry it off, let alone someone wearing just jacket and trousers, so one would assume that the thief must have been wearing the long Chinese-style coat called a dayi. So I said that it could not have been concealed by someone wearing a chuba, and this could be seen by putting another object of that size in the folds of a chuba for comparison, so although I could not say whether the thief was Chinese or Tibetan, it was likely that he was wearing a dayi.

Rikdzin Dorjé made no response, but basically the Cultural Relics Office suspected that a Tibetan working in the palace was responsible, and it was said that they secretly investigated the social backgrounds and contacts of these workers. When one of us, a young man named Chungdak, went off to China for training, they came and searched his dormitory room. For the next two years, the palace workers were under constant suspicion, until it turned out that customs officials in Guangzhou had apprehended a Chinese man trying to carry the statue out to Hong Kong.

Not long after I started working at the Potala, I noticed an item in a bulletin published for Chinese officials saying that a delegation of representatives from the Tibetan exile government was coming to Tibet on an inspection tour, and this was announced publicly in due course. People were told that they would be allowed to make inquiries with the delegation about their relatives who had settled abroad, but nothing else, and that they should receive the delegates courteously and refrain from showing anger toward them by throwing stones or showering them with dust. The reality was exactly the opposite. From the Tibetan point of view, young and old alike saw the exile delegation’s visit as a long-awaited moment that seemed to herald the dawn of a new and happier time. It was an opportunity to speak out about the sufferings endured by the Tibetan people up to now, to tell the truth about the prevailing situation and urge them not to be taken in by the false appearances put on by the Chinese, and especially for the delegates to understand the condition of the majority of Tibetans in rural areas, and I wonder if there had ever been such intense consultations and compilations of testimony in our entire history.

Most Lhasa people never learned when the delegation was supposed to arrive, but during the approximate period many of them stayed home from work in readiness to go and greet them in the traditional manner, by burning incense. The Chinese authorities, however, were being very cautious and kept the arrival date secret, as well as the name of the hotel where the delegation was accommodated, so that on the day of their arrival there was no big public welcome. But when they went to visit the Tsukla-khang temple the next day, Lhasa people gathered there immediately in their thousands and made plainly evident the agony of the Tibetan people, their unswerving devotion for His Holiness, and their loyal respect for His exile government. Not since the popular uprising outside the gates of the summer palace and on the Drébu Yulka grounds at Shöl in 1959 had such a large political gathering been assembled spontaneously and without the force of intimidation or bribery.

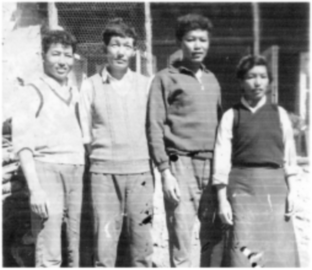

Lhasa 1979: from left to right, younger brother Jampel Puntsok, the author, late younger brother Ngawang Norbu, younger sister Tendzin Drölkar. Author’s collection

I did not join the crowd in front of the Tsukla-khang that day, but when the delegation visited the Potala, all of those working in the palace assembled to welcome and greet them in the Déyang-shar courtyard and make our feelings known to them, just as had happened outside the Tsukla-khang. That day, no one except the staff was allowed into the palace, and ordinary people were strictly prevented from approaching any nearer than the stone pillar in Shöl, so we got to meet them at ease, without the pressure of the crowd and, while inquiring after His Holiness’s health, to apprise them of the real situation in Tibet. At the same time, I found the opportunity to inquire after the whereabouts of my own relatives. When I asked one of the delegates whom I knew from before, the minister for security Taklha Puntsok Tashi, about my elder brother Yéshé Khédrup-la, who had fled in 1959, it turned out that he was a carrying a brief letter from Khédrup-la and a photograph.

For twenty years there had been no written communication between Tibetans inside and outside the country, and not knowing if each other were even still alive, they had abandoned hope of meeting again in this lifetime until the developments following Mao’s death began to allow for letters to be written and people to travel in and out. Thus, a short while before the arrival of the delegation I had been told by an acquaintance that my elder brother was alive and living in America, but that wasn’t much to go on. So with the letter and photo from the delegation to show that he was alive and well came the hope of seeing him again. More generally, when Tibetans who had been living under Chinese rule heard from the exile delegation about the activities of His Holiness and the situation of the exile government it gave them new hope and strengthened their resolve, and even those few who had believed the Chinese propaganda regained some confidence in their own people, changed their tune, and started to repent their views. On the individual level, families like ours that had been divided and had long remained in a state between hope and fear about whether their relatives were still alive had their doubts resolved one way or the other. The delegates had certainly accomplished the basic tasks given them by His Holiness and the exile government, even if some of what they had to say brought the people a few disappointments.

Apparently, after the return of the first Tibetan government delegation, the Chinese authorities held a review meeting, and one of the Chinese leaders declared, “We made two wrong assessments. First, we overestimated the members of the nonresident government, and second, we underestimated the Tibetan public.” What this meant was that since the exile government’s principal agenda was independence and its representatives were to openly discuss the two opposing perspectives on the history of Tibet, the Chinese side had taken them for qualified politicians with experience of a variety of social and political systems, familiar with domestic and foreign languages, and taken their reception very seriously, but they had not proved worthy of this assessment. This statement was probably a mandatory slight, but the underestimation of the Tibetan people was a serious error. Since they thought that most Tibetans held the Communist Party and the people’s government in reverence and loved socialism, it had never occurred to the authorities that there would be such a huge welcome and manifest display of affection and loyalty for the delegation, and the entire responsibility for this miscalculation had to be borne by the current TAR leader, Ren Rong. He had not only rigidly adhered to leftist policies and failed to implement the central government’s nationality policy but also was accused of having given the central government entirely false reports on every aspect of Tibet’s actual situation.

Then, a group of central leaders including the chairman of the Party secretariat Hu Yaobang, Party central committee Vice Premier Wan Li, and chairman of the Nationalities Affairs Commission Yang Jinren came to inspect conditions in Tibet at first hand. When they made a tour of the Potala, Hu Yaobang just glanced briefly at a couple of the golden reliquaries and apartments of the Dalai Lamas and showed little interest in the structure or contents of the fabulous edifice, but when they climbed up onto the roof, he looked out over Lhasa with a pair of binoculars and asked with great concern about all the official Chinese compounds, pointing them out and asking which office was which. He pointed to a Chinese-style pavilion in the middle of the ornamental pool by the “Cultural Palace” in front of the Potala and asked what it was, and on being told that it had been built as a recreation facility for the autonomous region leaders, he demanded sarcastically, “Who is enjoying themselves in there?” In the special meeting held a few days later, he apparently used this as an example when he stridently criticized local leaders for “throwing the funds provided by the central government in the Yarlung Tsangpo river” by wasting them on such things of no benefit to the needs of ordinary people.

On his departure from Tibet, Hu Yaobang declared that apart from the 20 percent or so of the Chinese population usefully employed in the region, like medical and technical professionals, the remainder should be withdrawn. The most senior TAR leader, Ren Rong, was appointed elsewhere in China and obliged to leave there and then, together with the central government delegation, and Yin Fatang, an official with experience working in Tibet, was called in from China as his replacement. Other Chinese leaders working in Tibet were also transferred, some offices were reorganized, and the positions of those central government cadres who had come to Tibet with little justification, by explicit appointment or otherwise, were rendered untenable.

Therefore the Chinese cadre force in Tibet was overtly or covertly hostile toward Hu Yaobang, and although their offices were powerless to defy his orders, the [regional] government ruled that the withdrawn cadres should be awarded a percentage of the wages due to them according to their period of service in Tibet in the form of a fixed allowance of Tibetan timber. Although the returnees were organized into three successive phases, all of them did their best to lay their hands on the timber allowance at once and to make sure that it was of the finest grade for making furniture, and fearing the trouble these discharged cadres might cause if disappointed, the heads of department let them do as they pleased. The first phase of Chinese cadres withdrawn in accordance with Hu Yaobang’s orders departed not long after, but the remainder who had laid claim to an allowance of timber ended up never having to leave.

The few who did leave took two or three truckloads each of possessions with them, and the timber and wooden chests they loaded onto those trucks were so heavy that they had to use cranes. At one point, a painted propaganda board in People’s Street in Lhasa that depicted a Chinese wearing a straw hat with a bedroll on his back and a tin bowl and wash bag slung over one shoulder, with the legend COMING TO BUILD THE NEW TIBET, had another drawing added to it of a big truck being loaded with a trunk so heavy it was about to topple the crane, and the legend RETURNING TO THE MOTHERLAND, which aptly expressed the real situation. They left, taking all these possessions, in broad daylight and with an irreproachable air, as if they were being as good as gold. Meanwhile, local leaders allowed thousands more Chinese to come in under cover of night without having to bring even bedding or eating bowls. In any case, apart from a few words and measures following Hu Yaobang’s visit, his instructions were never put into practice, and because of the timber allowance for the so-called returnees, Tibet’s forests had to suffer even more heavily.

Not long after that, the second exile government inspection tour composed of five members—four heads of foreign representative offices and the head of the exile Youth Congress—came to Tibet, and were warmly welcomed by the Tibetan public. They attracted large crowds wherever they went and spoke forthrightly about the activities of His Holiness and the situation of the exile government, and their tour seemed to be even better received than the first, although they were suddenly required to leave Lhasa before completing their itinerary. There were several factors behind this, but the immediate reason was that when the delegation traveled to Ganden to attend the Siu-tang festival, the employees of the municipal government’s handicraft sales center had put up a tent in the ruins of the monastery and arranged a reception for them; around a hundred vehicles came from Lhasa and thousands of people gathered there, and when the delegates addressed the crowd, the Chinese authorities panicked and obliged them to curtail their visit and leave early.

What I heard was that the then exile government representative in London, Puntsok Wangyal-la, made confrontational and accusatory remarks in his speech, to the effect that the neighborhood officials and activists who had served the Chinese by bullying and harassing their compatriots would have to be reckoned with in future. The young people sympathized with this and took the curtailment of the tour as a vindication, while many older people felt that his words had been quite ill judged and unwarranted, and by precipitating the delegation’s early departure, he had prevented them from fulfilling their appointed task. In any case, because of the crowd and the speeches made by the delegates at Ganden that day, they had to leave ahead of schedule, the names of many of those in the crowd were registered by the Public Security Office, and it was said that plainclothes police noted the registration numbers of the vehicles present and informed the offices to which they belonged, who then harangued the drivers and confiscated their licenses.

Soon after that came the third exile government delegation, which was received as well as the earlier two and successfully completed its mission. The visits by the three delegations allowed Tibetans inside the country and in exile to gain a clearer understanding of one another’s situation. With the impetus of the slightly improved conditions following Mao’s death, special efforts were being made for the perpetuation of Tibetan culture, and the opportunity arose for many older people with better knowledge of the written language to become employed as schoolteachers or in institutions concerned with cultural life. At that time, I heard that researchers were being recruited to staff the newly established Tibet Academy of Social Science, irrespective of whether they had participated in the uprising or were former “class enemies,” and I went to see the director, Amdo Puntsok Tashi, presented my credentials, and expressed an interest in joining. He asked about my background in some detail and told me to submit an application in writing, with my background and qualifications, so I wrote down my story from the age of eight until the present without concealing anything and handed it in. About three weeks later, I was called to take the academy’s standard examination, which I did under the supervision of a few of the academy’s staff, and before long I received a letter of acceptance.

From 1959 up until a couple of years before that, I had labored under the “proletarian dictatorship” like an animal without so much as a sesame seed’s worth of personal freedom, obliged to run at the beck and call of others, but now, with the turning of the wheel of time, I had been included in the ranks of the salaried officials of that same state and government. But if my hardships were less than before, it was not as if I had been granted freedom of thought or speech. The very purpose of establishing that academy, for example, was to assemble documentation to show that Tibet was an inseparable part of China and that many aspects of Tibet’s intellectual and material culture had been introduced by the Chinese princess Kongjo, and other propositions quite at odds with reality. We were still living with the same terror of persecution and incarceration if we tried to give voice to the real situation.