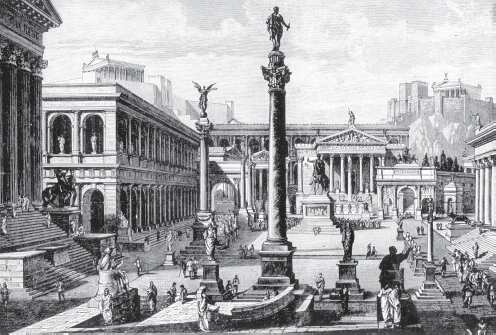

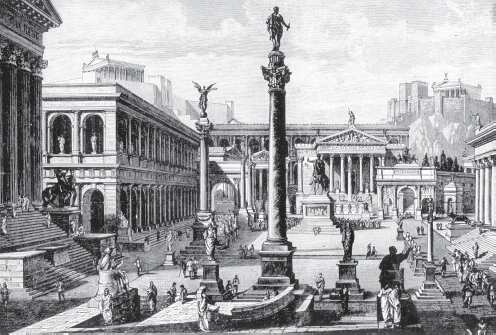

Rome, Forum Romanum, daily life in the Roman Forum. Shown from left: Temple of the Dioscuri, Basilica Julia, Temple of Concordia, Triumphal Arch of Septimius Severus and Carcer Mamertinus. In the background is the Capitol.

From Citizenship to Imperial Rule

The lessons of citizenship developed by the Greeks reached full maturity in Roman history. Yet ancient Rome experienced two distinct political episodes: the first revolved around the power of citizenship as developed in Greece and rejuvenated in Italy (ca. 509–31 BCE); the second around imperial rule (31 BCE-476 CE). Both episodes, however, revealed the political consequences of the use of iron technology as Rome shifted from a city-state to a great empire like those established by Assyria, Persia, and Macedonia. The two episodes of the Roman story, thus, represent both the complexity and the culmination of Western political culture during the ancient era, as well as the power of iron and the dynamic energy of citizenship in Western history.

Roman citizenship imitated the Greek model by combining the Greek concept of civic virtue with the Greek phalanx and iron technology. Yet in the first 244 years of the Roman Republic (509-265 BCE), Rome dramatically changed the Greek ideal of the citizen. The Romans did so by doing something that was unthinkable to the leaders of Greek city-states: they created a stable federation by establishing more than one level of citizenship in the empire. Rome produced the first version of this political innovation at the end of the Latin War (340-338 BCE).

The Latin Wars grew out of difficulties between a set of Roman allies that Rome had previously recruited into the Latin League. These allies occupied Latium, a region in central Italy that Rome had captured through warfare from 509 to 338 BCE, hence the name of the league. The Romans had placed the defeated Latin cities into an alliance to enhance Rome’s strength, but the allied cities did not share equally in the spoils that followed. The Latin Wars settled the matter, in that they inspired Rome to create a three-tiered system of political identity: fully incorporated cities, partially incorporated towns, and dependent allies. Fully incorporated cities were adopted into the Roman state; their inhabitants became the equals of Roman citizens, including having the right to marry Romans, vote, and hold public office in Rome. The residents of partially incorporated towns received limited citizenship; their inhabitants could intermarry with Roman citizens but could not vote or hold office in Rome. The dependent allies were subordinate states; they were not incorporated into the Roman Republic and were compelled by treaty to cede their public lands, but they were allowed to retain their local governments. Finally, Rome expected all three tiers of this new political federation to lend troops and material support during times of war and submit to Roman foreign policy.

This three-tiered system was part of a larger, complex system of political designations in which people held a different status depending on where they lived. In the Roman system, cives Romani were Roman citizens; coloniae Romani, were Roman colonists with civil status; municipia, were Latin cities whose residents had limited citizen status; and latini, were dependent Latin allies of Rome. Since 338 BCE, Rome had added socii, or Italian allies, to the Roman federation, and provinciates, or free subjects of Rome living outside Italy.

The second critical change that the Romans made to the Greek concept of citizenship followed the same circumstances as the first: it involved a war in which the Roman allies again demanded equality with Rome. This second war, the Social War (91-88 BCE), got its name from the status of a second set of allies; the socii, Italian cities Rome had conquered and assimilated after acquiring the Latin League. They found themselves fighting wars they had no control over, taking more risks than Roman citizens in expanding the empire, and not sharing equally in the spoils. Frustrated by Rome, the socii rebelled and declared their independence in 91 BCE, forming a new state called Italia. Rome saved the empire by undercutting the enemy forces. Rome offered full cives status to the residents of any allied Latin or Italian state that remained loyal to Rome after hostilities had begun; Rome also offered cives status to the residents of any allied state that laid down its arms before a specified date. Then Rome defeated any state that refused these offers. When the Social War ended, 500,000 new cives had been added to the Roman rolls.

Rome, Forum Romanum, daily life in the Roman Forum. Shown from left: Temple of the Dioscuri, Basilica Julia, Temple of Concordia, Triumphal Arch of Septimius Severus and Carcer Mamertinus. In the background is the Capitol.

Rome’s willingness to add the residents of other Latin and Italian cities to the citizen roles or to enlist allies by holding out the possibility of its citizens gaining Roman citizenship later generated such a large military base that it produced an empire far more imposing than any Greek city-state ever was able to govern. Each Greek city that had tried to expand its holdings ended up capturing more than its citizens could control. Accordingly, they all fell victim to anti-imperial military alliances designed to preserve the city-state system during the Peloponnesian Wars (431-338 BCE).

Rome, in contrast, had created a sufficiently flexible definition of citizenship to allow its military to expand at the same pace as its empire, so Rome remained the political center of a growing social and economic system. Hence, unlike the great Greek network cities such as Athens, which had relied so heavily on long-distance trade to feed its urban population, Rome became the first centerplace city of the Mediterranean world.

Reinforcing Rome’s role as the centerplace city of Western civilization was a major military innovation, the transformation of the Greek phalanx into the Roman legion. The design of the massive phalanx entailed continuous parallel ranks of hoplite citizen-soldiers that reached as far as their numbers would allow. Such a formation forced Greek armies to stage battles on whatever flat lands they could find. The Romans followed in this tradition until they confronted an enemy that took refuge in the Apennine Mountains, at which point they realized the need for more flexibility.

In the Samnite Wars (328-290 BCE), Romans had to modify the phalanx to create a sufficiently flexible military formation capable of fighting in rough terrain. The legion broke the continuous ranks of the phalanx into separate units called maniples (“handfuls” in Latin). Each maniple functioned as a subunit whose commander coordinated with the general of the entire legion. With its maniples arranged in an infantry formation that resembled the dark squares in the first two rows of a checkerboard, a legion could confront an opposing force as a staggered line of resistance, making it very difficult for the enemy to break completely through the line.

With each of its 120 heavily armored infantrymen toting two pilia, heavy spears made of iron and oak, a maniple formed a tightly packed and formidable unit. Rather than relying on the impact of a massive formation of all available men, as in the case of a phalanx, each soldier in a legion threw his two spears prior to engaging in combat at close quarters with a short iron sword. When thrown, the pilia stuck in the enemy’s shield, weighing it down and exposing its bearer to the swords wielded by the Roman soldiers. Furthermore, the shock of the staggered assault line proved far more effective than the even contact of the lengthy ranks marshaled in the phalanx. Finally, a top Roman commander usually had several legions at his disposal, numbers that allowed him to attack on more than one front at a time. As a result of this innovation, Rome won nearly all its land engagements.

Rome’s military success eventually created an empire too large for a simple republic and the noble concept of civic virtue to govern effectively. Slow growth in Rome’s first 244 years prepared it for its first great overseas challenge when it confronted Carthage in the three Punic Wars (264-241 BCE, 218-202 BCE, and 149-146 BCE). The Romans’ ultimate success against Carthage allowed Roman civilization to expand beyond populations that understood Roman citizenship, civic virtue, the legion, and Rome’s process of assimilating new allies. The massive numbers of subject peoples Rome added to its empire in merely sixty-two years (264-202 BCE) overwhelmed its own citizen population.

After 201 BCE, Rome’s vast new acquisitions proved too much for it to handle. Victory in the second Punic War over Rome’s most talented enemy, the great general Hannibal, had added half the Mediterranean world to its empire. At the same time, defeating Hannibal had required Rome’s armies to spend fourteen years in a siege-like state, during which the Carthaginians had occupied Italy. This long siege had separated Roman farmers from their land and eroded the pre-eminence of the farmer-soldier in the Roman army.

Hannibal first threatened Rome when he crossed the Alps after having marched overland from Spain to invade Italy in 218 BCE. He followed this spectacular feat with a series of victories at Trebia, Lake Tassimire, and Cannae between 217 and 216 BCE. These victories drove Rome from the field with devastating losses. Having lost a generation of soldiers, the Romans could no longer fight Hannibal, even as Hannibal discovered that he did not have enough men left to capture Rome itself and end the war. Thus, the Romans began an era of recovery under Fabius Maximus, the Great Delayer.

During the fourteen years that Hannibal wandered about in Italy incapable of attaining a clean victory, Roman farmers had to live in Rome proper. There the cives grew accustomed to accepting military assignments and the generous support of Rome’s leading families. When the war finally ended with Hannibal’s defeat at Zama in 202 BCE, a generation of Roman farmers found it difficult to return to the land. Having become dependent on great Roman families, these farmers had become addicted to war. Therefore, between 201 and 133 BCE, they found themselves on campaign in Spain, North Africa, Macedonia, Greece, and Anatolia.

Abandoned farms in Italy came up for sale. Those who purchased these old farms used the estates to form latifundia, the most successful farming units in Italy after 201 BCE. Latifundia were large estates developed as commercial plantations and worked by slaves captured in war. The patricians, Rome’s ancient aristocratic families, became the owners of these enormous farms and soon drove the remaining small farmers who had returned to the land out of business. According to Roman law, however, most of these new plantations exceeded the maximum legal size that a Roman citizen could own.

The latifundia naturally concentrated power in the hands of the patricians. They constituted Rome’s original citizen families, the populus Romanus of the sixth century BCE, and they had watched their political authority erode under pressure from the plebeians, the farmers from the rural areas who fed Rome. Conversely, between the sixth and third centuries BCE, the plebeians had struggled to achieve political equality with the patricians and had succeeded in acquiring access to nearly all the major offices of the Roman magistracy because of their value as farmer-soldiers. But the plebeians now faced a political crisis as patrician-owned latifundia undercut the farmer-soldiers’ role in the Roman economy and politics. Thus, between 201 and 133 BCE, the patricians regained control of the magistracy, the Senate, and foreign affairs. Also, the patricians had discovered that controlling foreign policy allowed them to accumulate fresh spoils of war to fuel the continued erosion of plebeian power. The patricians imposed a war policy that took the Roman farmer-soldier (the plebeian) away from his land for long periods, which increased the risk of the farmer’s family sliding into bankruptcy and reduced the willingness of the citizens to serve in the military.

Among the plebeians, rich families who had gone into business could compete with patricians by using the office of the tribune. The ten tribunes were state censors (guardians of morals) whose role allowed them to protect the interests of the poor against the patricians. A man who sat as a tribune was immune to prosecution, could veto a senatorial policy, and could declare a secessio—an event in which the plebeians withdrew from Rome when the patricians grew too demanding. The office of tribune served to secure the rights of the plebeians under the constitution by forcing the patricians to act with moderation. Yet in time, the spoils of war also undermined the ethics of tribunes. To gain a better understanding of Roman politics, a review of Rome’s constitution is in order.

The Roman constitution was not a written document as found in the United States; rather, it evolved in a manner similar to the British constitution. The Roman constitution was complex and somewhat confusing. It comprised: a system of magistrates that performed critical functions within the state; the Senate, which debated policy and initiated laws; and the popular assemblies, which ran elections and passed laws. The first element of the constitution was the magistracy, which essentially ran Rome and included a number of critically important offices; these included the censors. The holders of the highest office in the magistracy, the censors were two elected officials who served eighteen-month terms in oversight of public morals, the disbursement of state funds, and the taking of the census. Next came the consuls, or chief civilian and military leaders, who presided over the Senate, proposed laws, ran civilian affairs, and commanded Rome’s armies. Third were the praetors, who served as judicial officers and provincial governors, and in this latter role they held local military command and collected taxes. In support of the praetors were the quaetors, of financial officers in the provinces. Back in Rome, there were the aediles, who presided over public ceremonies and games and also served as the city’s managers. Last came the tribunes; these were the guardians of the plebeians who proposed laws and presided over the Plebeian Assembly, which passed or rejected all Roman legislation. The tribunes also possessed the power of veto and secessio mentioned above.

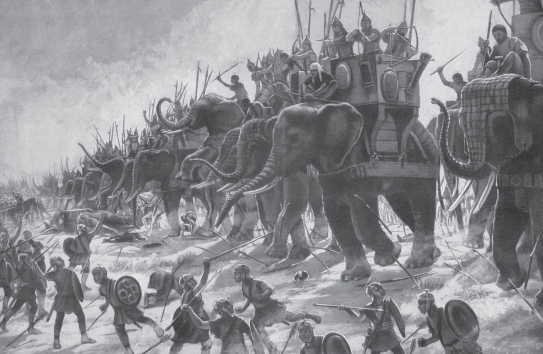

“The Battle of Zama” Painting by Henri Motte (1846–1922) of the battle which took place near the end of the Second Punic War 218-201 BCE in which Scipio defeated Hannibal.

Roman coins. Top, Julius Caesar, ca. 46 bce. On the reverse (right) are ceremonial emblems—ladle, aspergillum (to sprinkle holy water), and jug. Bottom: Octavian, shown as the god Apollo, ca. 30-29 bce. On the reverse he is shown as the city founder, holding a whip and ploughing with oxen.

Besides the magistracy, the Roman constitution included the Senate. The patricians tended to dominate the Senate, their wealth and prestige giving them a powerful voice in state affairs. The Senate’s functions included command over Rome’s finances, provincial administration, foreign policy, and the assignment of military commands. The Senate also served as an advisory body to the magistrates, administered public lands, and on rare occasions declared a state of emergency and appointed a dictator for a period of six months. The membership of the Senate included 300 total and to become a member one had to meet a property qualification of one million sesterces (Rome’s primary silver coin) plus be at least thirty-two years of age and have an outstanding record of public service.

In contrast to the Senate were the popular assemblies in which Roman citizens passed all of Rome’s laws and ran its elections. The first of these assemblies was the Centuriate: its membership included all male citizens, and its function was to elect censors, consuls, and praetors, declare war, ratify treaties, and serve as an appellate court for capital offences. The second was the Tribal Assembly. It comprised all male citizens and elected aediles, quaetors, and created special commissions. The third and most effective was the Plebeians Assembly, which served as the counterweight to the Senate; it included all male citizens, elected tribunes, and functioned as the chief legislative body by acquiring the power of the plebiscita after 287 BCE when the plebeians’ military service allowed them to force shared power with the patricians.

According to Roman tradition, patricians should not engage in business; their income should derive solely from agriculture. This left the field of business open to plebeians, many of whom grew wealthy. At the same time, one of the most successful business ventures during these years of warfare was the issuance of war contracts. These contracts secured the supplies needed for Roman armies and collected a good share of the spoils won. Since this buying and selling meant profits at both ends and since these contracts usually belonged to the rich plebeians, the wealthiest plebeian families tended to support those senatorial policies that launched wars. Also, the richest plebeians came from the same families who provided individuals who could afford to serve a year without pay as a tribune. Hence, those tribunes who should have censured corrupt patricians increasingly had an incentive to join them in starting wars that might turn a profit.

What followed is one of the most studied eras of Western history: the Roman Civil War (133-31 BCE), in which generation after generation of Roman leaders came forward to claim control of Rome’s politics only to set patricians and their clients against rich plebeians and their popular politics. Each generation failed to resolve the conflict until Rome’s republican form of government finally gave way to imperial rule.

The first generation that attempted to seize power, launching the political strife that led to civil war, were the Gracchi brothers, Tiberius (d. 133 BCE) and Gaius (d. 121 BCE), who together formed the populares (Popular Party). Both held the office of tribune and sought land redistribution in the hope of restoring Roman farmers to their role as the building block of the legion. Their efforts led to the assassination of Tiberius and forced suicide of Gaius at the hands of senators who would have lost their latifundia to these land programs. Their deaths divided Rome and defined the two poles in the contest: the populares versus the optimates (Senatorial Party).

The next generation pitted Gaius Marius (155–86 BCE) against Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138–78 BCE). Marius redefined military service so that a man who fought for twenty years earned retirement and a new farm. This program transformed the Roman army into a political group loyal to a talented general. And such talented generals now took control of Rome’s legions, paying their soldiers with the spoils of war. These generals became the leading political figures in Rome. Marius used this program first to direct the populares, while Sulla developed the same strategy to organize the optimates. Both generals knew that whoever commanded Rome’s armies commanded Rome’s politics. Since Sulla outlived Marius, the optimates took control of Rome at the end of this generation.

The third generation saw Gaius Julius Caesar (102–44 BCE), nephew to Marius, lead the populares, joined by Marcus Lucinius Crassus (d. 53 BCE), a rich patrician land speculator who had as much ambition as money. Together they formed a power block with Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (or Pompey, 106–46 BCE), the famous conqueror of Armenia, Syria, and Palestine. Friendly rivals as long as all three were alive, Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey offset the power of the senate and the optimates. Their association was an uneasy one, but it lasted until Caesar’s conquest of Gaul gave him a military reputation equal to that of the great Pompey, right about the time that Crassus died in battle trying to capture Parthian Persia (see chapter 8).

In the war that followed, this third generation finally resolved some of Rome’s outstanding issues. Caesar defeated Pompey at Pharsala and followed him to Egypt. There the Macedonian pharaoh, Ptolemy XIV, murdered Pompey, which motivated Caesar to join with Cleopatra to secure control of Egyptian politics. Pompey’s defeat at Pharsala also saw the death of most of the senatorial families. Thus, when Caesar returned to Rome after a brief campaign in North Africa to eliminate the remnant of the Senatorial Party, the way was clear for him to establish a dictatorship. His assassination in 44 BCE, however, prevented this outcome.

Before the civil war ended, one more generation of leaders took power. Now the conflict was between Caesar’s heirs: Gaius Octavius (63 BCE-14 CE) and Marc Antony (83-30 BCE). Gone were the optimates as rivals, meaning that the victor of this contest had a clear path to redefining the politics of Rome. Octavius defeated Antony and his ally Cleopatra at the battle of Actium in western Greece (31 BCE), drove Antony and Cleopatra to suicide, captured the riches of Egypt, and linked grain production in the Nile Valley to a new Roman government. Octavius’ victory concentrated all the power of Rome in the hands of one man. Octavius solidified his position by carefully manipulating his public image to allow him to avoid assassination, the fate that had befallen Julius Caesar. Thus, at the end of his career, it was Octavius who converted Rome to imperial rule.

According to Roman tradition, patricians should not engage in business; their income should derive solely from agriculture. This left the field of business open to plebeians, many of whom grew wealthy. At the same time, one of the most successful business ventures during these years of warfare was the issuance of war contracts.

After the fall of the Roman republic and the beginning of the Roman principate, the next five hundred years of Roman political development linked the resources generated by iron technology to the ancient concept of kingship. This form of government had reached its apex in the ancient Near East. Building on examples of monarchy that dated back to the first imperial ruler, Sargon the Great (2344-2279 BCE), during the Bronze Age, Rome instituted an Iron Age empire like that of the Assyrians, Persians, and Macedonians. The Roman monarchy marked the end of a political evolution in the West that had begun with the widespread diffusion of iron tools and the evolution of the Greek concept of citizenship. Thus, even though it borrowed heavily from the past, the Roman model became dominant in the West and developed into the most elaborate empire based on a single centerplace city that the ancient world had seen.

Even though it borrowed heavily from the past, the Roman model became dominant in the West and developed into the most elaborate empire based on a single centerplace city that the ancient world had seen.

In turning to rule by a god-king (a model that had served the ancient Near Eastern emperors very well), Rome adopted a pattern of government that violated its original design based on citizenship. Professional armies replaced citizen-soldiers, as the military ceased to be a means of directing the political loyalty of farmers to their city. An older pattern of submission and obedience returned, as Roman farmers lost their sense of civic pride and political duty to serve their city. Once again, farmers came to distrust urban dwellers, seeing towns as comprised merely of revenue-hungry parasites. Such an erosion of citizenship cut the bonds that held Western culture together.

Lost was the power that had launched the Roman Empire: that key integration achieved when the discovery of iron smelting set in motion the ties between the farmer, citizenship, civic virtue, the phalanx, and the legion. The loss of civic virtue and citizenship, in turn, created a new hunger for social identity that only religion could fill. This hunger laid the foundation for Rome’s experimentation with foreign faiths. Into the empire trickled Manichaeism, Egyptian cults, and Christianity. Among these rival faiths, Rome ultimately settled on Christianity.

The victory of Octavius (now Octavian Caesar) over Marc Antony at Actium in 31 BCE ended the Roman civil war (133-31 BCE) and left Rome with only one ruler. Fearful of Julius Caesar’s fate, death by assassination, Octavian began a process of political innovation that preserved the institutions of the republic while carefully constructing imperial rule. Rejecting any indication of being a king, yet ruling with the authority of an emperor, Octavian collected a series of titles, bestowed upon him by the Senate, that placed absolute power in his hands. Hence, he maintained the façade of Roman traditions, political forms, institutions, and public relations, while creating a new method of administering Rome’s vast holdings.

Accepting the titles of Princeps (or “first citizen,” from which comes the word prince), Imperator (“victorious commander,” from which we get emperor), Augustus (great and holy one), Pontifex Maximus (high priest), and Tribune for life, Octavian set about establishing personal sovereignty. Preserving the Senate, Rome’s aristocracy, the elected Roman magistracy, and Roman citizenship, Octavian managed to create the illusion of a dyarchy (the rule of two: supposedly one was Octavian and the other the Senate), but in fact all decisions of importance passed through his hands first, while he staffed the Senate with men loyal to him. Over time, his paper titles truly described the magnitude of his power. Eventually he ceased being known as Octavian Caesar and became Augustus Caesar. Also, to acquire Augustus’s prestige, his heirs assumed the name of “Caesar” as a title until the Emperor Diocletian (reigned 284–305 CE) replaced it with “Augustus” and bestowed “Caesar” on his heir apparent. All the remaining Roman emperors then followed Diocletian’s example. While the Augustus ruled civilian life, the Caesar guarded the frontier against “barbarians” as training to rule the empire. By Diocletian’s time, Rome faced enormous pressures on its frontiers from nomadic invasions and needed leaders well trained in the art of war (see chapter 11).

Augustus used the Senate to run the civil administration of Rome and the provinces. Yet because of the death of so many of Rome’s ancient families during the civil war, he was able to raise trustworthy supporters to the standards of honor, wealth, and conduct that the name “senator” required. Accordingly, he knew he could turn over decisions to the Senate while in fact ruling through this now loyal, stabilized body. Meanwhile, he remained in command of the army, some twenty-six legions deployed along Rome’s frontiers; maintained exclusive ownership of Egypt as a private imperial estate; and had a personal security force of 9,000 Praetorian Guards. Hence, Augustus had at his command more than 350,000 soldiers, enough grain to feed Rome’s poor citizens, and held a monopoly on coercion within the 2.2 million square miles of the Roman Empire.

Casting himself in the role of Rome’s military protector, high priest, and reviver of historical tradition, Augustus restored as much of Rome’s past glory as he could. He paid particular attention to the worship of Venus (the name Romans had given to the Greek goddess Aphrodite when they adopted the Greek pantheon) because Julius Caesar had traced his ancestry to this deity of love and passion. This attention to detail allowed Augustus to link Caesar’s name to the ancient Trojan warrior Aeneas, the son of Venus and a founder of Rome, and sponsor such works of art as Virgil’s Aeneid. To serve Augustus, Virgil (70-19 BCE) tried to imitate Homer and create a patriotic epic that told of the Trojan survivors who followed Aeneas (hence the title Aeneid) first to Carthage and then to Italy to lay the foundation for Rome. Also, Virgil instilled in Aeneas the virtues—stern rectitude, devotion to family, and care for the state—that became the backbone of Roman polity. The Aeneid described the establishment of Rome as a product of a divine plan, made the Romans the heirs of Troy, and transformed Augustus from a mere human into the scion of lineage, in other words the genius (guardian spirit) of Rome. In short, everything Augustus did fostered his power either directly or indirectly.

Imposing a strategy for peace that lasted until 180 CE, Augustus established a style of rule that sheltered the empire from profound internal disorder. He did so by encouraging the expansion of the economy, restoring fiscal stability, and securing empire-wide productivity. He knew that people everywhere were exhausted by war and hungered for peace and stability. He knew that 102 years of civil war had eroded the empire internally and left the Italian peninsula in chaos. And he knew that if he could provide the people the material security needed to recover the productive potential of Rome’s vast holdings, Romans everywhere would be willing to accept citizenship in name only. Accordingly, he inaugurated an era of political stability, commercial prosperity, and agricultural productivity. At his death in 14 CE, the chaos of the past had become a distant memory.

Statue of Octavius (Octavian Caesar or Agustus Caesar).

But the one problem that Augustus could not solve was this: how would he choose a successor? Passing absolute power from one generation to the next while maintaining the façade of the republic over an empire proved to be too difficult even for someone of Augustus’ abilities. Upon his death, he was left with no choice but to transfer authority to Tiberius Caesar (reigned 14–37 CE)—his most talented surviving heir. Augustus had no son of his own, and numerous candidates he considered as heirs died early; his wife, however, had Tiberius as a son by a previous marriage, so Augustus adopted her son to create a successor. Using the principle of heredity, Tiberius then passed power to his nephew Caligula (reigned 37–41 CE). Caligula, however, proved to be insane and only assassination saved Rome. This act brought Claudius to the throne (reigned 41–54 CE); finally, Claudius’s son Nero (reigned 54–68 CE) took over after the death of his father, but insanity once again marred the imperial office and sedition forced him to commit suicide. His reign would mark the end of the first Roman imperial line.

These four men, plus Augustus, made up the Julio-Claudian line. Ironically, Augustus alone was the only major talent among them; Tiberius and Claudius were competent but uninspiring. Caligula and Nero were both deranged and had to be removed from office. By the time of their unsuccessful reigns, the façade of republicanism so carefully constructed and maintained by Augustus had become less and less important. Hence, the material benefits associated with Roman citizenship also began to erode. Eventually, citizenship itself became a hollow shell, the legal and material advantages of this status having fallen victim to the harsh realities of imperial rule.

Although the Augustan reign had been hailed as the golden age of Rome because of the peace, prosperity, and stability it brought with it, something had died along the way. Rome’s intellectuals, historians, and artists lamented this loss. Each in his own way spoke of a sense of decay that had begun with the end of the republic. Each described a present world in which material success was unquestioned but meaningless when compared to the loss of the civic virtue, rigorous discipline, and political morality that once had marked Roman life.

Following the death of Nero in 69 CE came the Flavian line. One year of civil strife brought Vespasian (69–79 CE), founder of the line, to power, and again Rome had a hardworking, conscientious, and competent professional soldier on the throne. Vespasian revived the economy, restored peace, and reasserted Augustus’ administration of the provinces. But because he had two sons, Vespasian relied on inheritance as the means to pass on his power. Accordingly, Titus began his rule upon the death of his father, but this lasted only two years; a deadly fever cut short his reign (79–81 CE). Vespasian’s second son, Domitian (81–96 CE) lasted longer and proved to be an able ruler, but in time he became paranoid. He created a system of secret police that terrorized his subordinates, a practice that eventually led to his assassination fifteen years after he had taken office. Hence, the Flavian line did not fare much better than had the Julio-Claudian line.

One innovation, however, did come out of this flawed method of the transference of power. The assassins who removed Domitian agreed to replace him with a man of unimpeachable character, Nerva (96–98 CE), who ruled quite briefly but who, notably, selected his own heir, Trajan (98–117 CE). For the next eighty-two years, that is until the end of the Pax Romana (Pax means “peace in Latin, but here serves better as “stability”), the emperors of Rome had finally hit upon a method for selecting competent heirs: adoption. Trajan selected Hadrian (117–138 CE), who selected Antonius (138–161 CE), who selected Marcus Aurelius (161–180 CE); each of these men proved to be an effective and charismatic leader. Hence, Rome enjoyed an unbroken chain of command by men capable of inspiring loyalty and good will. Yet Marcus Aurelius failed to maintain this standard of rule, for upon his death his son Commodus (180–193 CE) took over and later became insane.

Although the Augustan reign had been hailed as the golden age of Rome because of the peace, prosperity, and stability it brought with it, something had died along the way. Rome’s intellectuals, historians, and artists lamented this loss. Each in his own way spoke of a sense of decay that had begun with the end of the republic. Each described a present world in which material success was unquestioned but meaningless when compared to the loss of the civic virtue, rigorous discipline, and political morality that once had marked Roman life. The imperial office was occupied by great men, but only when lineage or inheritance was ignored. From Augustus to Commodus (31 BCE-196 CE), seven gifted rulers brought peace to Rome, but in between their reigns fell four competent but uninspiring men and three lunatics.

The wealth of the empire derived from an economy initiated by Augustus and maintained by the “good” emperors. This economy began with agriculture and centered on commerce. The heart of the empire, the Italian peninsula, held numerous latifundia and medium-size farms big enough to diversify productivity. Since Egypt had become the granary of the empire under Augustus, Italian farmers could afford to produce a wide variety of crops designated for export as a hedge against bad agricultural years. Those farmers who could not afford to experiment with different crops could instead specialize in such luxury items as wine and olive oil because of the high profit margins these products commanded. And during the prosperity of the Augustan era, the demand for luxury goods in general grew so high that the raising of heretofore frivolous livestock such as poultry, pheasants, and peacocks became economically feasible. Finally, since all roads led to Rome at this time, it became the commercial center of the Western world.

Italian industry also grew dramatically under Augustus’ care. Since he used rich plebeians to staff the financial bureaucracy he had constructed to run the empire, he encouraged the formation of a new business class. In addition, since Augustus had launched a major reconstruction of Rome and the empire after the devastation caused by the civil war, the demand for building materials was great. Mass production based on slave labor generated ceramics, bricks, tiles, and hard metals. Accordingly, the new business class grew as a needed imperial counterweight to potential senatorial corruption. At the same time, a vast new supply of building materials fueled a Roman economic revival.

In the provinces, meanwhile, prosperity followed on the heels of peace and stability. Egypt produced the grain needed to feed Rome as well as the fine sand needed to maintain its glass industry. At this time, Alexandria became the entrepôt for the eastern Mediterranean. A new wave of trade in the Aegean and Black seas revived local economies and linked the eastern Mediterranean with the west. Hence, Rome became a centerplace city in a growing economy, one whose prosperity generated its own momentum as long as the general population remained healthy. Despite the periodic rule of literally insane emperors, the Roman economy managed to survive well during the Pax Romana.

But as mentioned earlier, the material wealth of the empire could not compensate for the sense of spiritual loss that plagued Rome after 31 BCE. As a result, many Romans began to look for a new spiritual substitute to replace the real sense of citizenship they once enjoyed. Many people turned to foreign religions and Greco-Roman philosophy as a means to recover what they felt was missing in their lives.

The Roman family formed the backbone of society. Romans lived in complex households with a central bloodline, close relatives, multiple generations, free servants, and slaves. The head of the household, the pater familias (father of the family), governed the subordinate members with the power to inflict capital punishment on any member who brought shame on the family. The pater familias made all the key decisions for the family: marriages, finances, politics, rights, duties, obligations, and punishments. A key element of the power of the pater familias was manus, the authority of a husband over his wife. The concepts of pater familias and manus subjected Rome’s women to the will of the male members of the family.

An example of the way the authority of the pater familias worked is the traditional Roman interpretation of rape. If a man raped a woman, he was guilty of a crime, but since the woman was a participant (even though unwilling), the family still held her partially responsible for the act. If she died as a result of the sexual assault, she was judged innocent, because she had given her life to protect her family’s honor. If she were severely injured but survived, she was judged partially guilty and punished according to her wounds—the more severe, the greater her degree of innocence. If she displayed few injuries, then the pater familias, acting on behalf of the family, judged her guilty of willfully participating in the act, probably because he believed she had incited it, and ordered her buried alive as if she were an adulteress. Such oppressive authority over women, however, eroded as the Roman republic acquired more wealth through conquest.

Quirites (Romans) with their Sabine wives and sons approaching the sacred place to offer thanks to the gods for their blessings.

Roman patrician being dressed and groomed by her servants.

Between 265 and 31 BCE, women gained more freedom from male domination as their ability to supervise the family’s household made them personally rich when the spoils of war poured into Rome. Although Roman law strictly limited the ability of women to inherit estates, the inconsistent application of these legal constraints allowed many women to become independently wealthy after their fathers and husbands died. Between 200 and 31 BCE, as Rome gained command of the Mediterranean world, clever individual females managed to procure massive estates that rivaled the wealth of the richest families. Accordingly, such women even managed to escape the authority of the pater familias and manus to become heads of their own households.

Also, newly rich families that managed to survive the Roman civil war and benefited from Octavius Ceasar’s freshly instituted Pax Romana (31 BCE-180 CE) swelled the ranks of merchants, manufacturers, builders, and landowners. They represented the social fluidity of Rome’s status system, in which those with talent who could correctly estimate the direction of political and economic developments prospered. Serving as a new source of consumer demand, these newly rich families stimulated a new market in exotic luxury items, such as parrot-tongue pie, ice cream, and jellyfish, to name a few. Also they engaged in conspicuous consumption on a grand scale, hosting elaborate orgies punctuated with sumptuous banquets that included periodic vomiting to make room for more food.

At the other end of the social scale, a growing mass of urban poor became a major political problem after the second century BCE. Unemployed, rootless, and willing to sell their votes for the legal and political protection of any wealthy family, these indigent masses swarmed through the streets of Rome, rioting to ease their misery and readily joining the army of any ambitious general during the civil wars. The poor became a special concern of Octavius Caesar after his victory at Actium in 31 BCE; he used his newly won holdings in Egypt to feed any citizen in Rome who asked for free bread. To this benefit of free food, Octavius added the circus, which became an imperial monopoly so that he could supply ample entertainment—particularly blood-soaked gladiatorial contests—to ease potential unrest and calm the urban masses.

At the very bottom of society were the slaves. Roman society ran on slave labor. By the second century CE, 33 percent of the Roman population was comprised of slaves doing one form of work or another. Some 19.8 to 24.8 million of an estimated total of 66 to 75 million people living in the empire were enslaved. Nearly all of these people were captives taken from conquered lands added to the empire, because those who became Roman slaves did not reproduce their numbers.

These slaves worked the latifundia, formed the labor force of Roman factories, provided most household services, and were some of the best educated people of the Roman world. Women slaves commonly supplied domestic labor and sexual entertainment, while men did everything imaginable: they trained as gladiators (e.g., Spartacus, the man who led the slave revolt of 73 BCE); worked as teachers, craftsmen, or servants, and functioned as business agents. Yet most male and female slaves led such miserable lives that they failed to form families and reproduce. Hence, the total number of slaves began to decline after Rome expanded to its maximum size.

At the height of Roman power, at Augustus Caesar’s death in 14 CE, the empire comprised an estimated 4.9 million citizens. These people represented as little as 6.6 to as much as 8.3 percent of the total Roman population. This small percentage of the whole, however, constituted the empire’s elite: nearly three million lived in Italy, with the remaining two million in the provinces. In 212 CE, 198 years after Augustus’ death, the emperor Caracalla officially proclaimed all freeborn males within the empire to be citizens; thus, by the third century CE, citizenship had become so common it was meaningless. No longer the political identity that gave purpose to public life, being a citizen now meant that all freeborn men living within the empire belonged to a vast, diluted pool of people with no real role in politics. Meanwhile, 85 percent or more of Rome’s people made their living from agriculture; this meant that only between 9 and 11.3 million Romans lived in its more than one thousand cities. The Roman empire achieved an unusually high urban-rural ratio of 1.5 to 8.5. This was probably due to the productivity of Egypt, the Roman breadbasket, where the fertility of the Nile Valley never waned throughout its long history.

In summary, then, one could say that Roman society was a fluid mass shifting with each passing year. Prosperity offered opportunity for the few who were competent and clever after the civil war. Fortune smiled on those with self-confidence and good economic and political judgment—including women. Yet if a person guessed wrong about the events of the day, especially during the reign of an unstable emperor, ruin soon followed. Near the bottom of society, the poor, the homeless, and the destitute teemed the streets of the Roman empire’s major cities. They could be distracted by gladiatorial events and fed free bread if they held Roman citizenship and lived in Rome, but there was no coherent policy to deal with the masses of urban poor. At the very bottom of society, the slaves represented a massive, unstable labor pool whose misery prevented them from replacing their own numbers. Hence, the future of Rome rested on a cunning, self-absorbed elite capable of guessing the direction of political developments; the poor, urban masses unsure of what the future would bring; and a labor base that could only shrink after Rome had grown to its maximum size.

The Roman philosophical perspective matured in an era of increasing demoralization as the Roman empire first lost its sense of direction during the Pax Romana (31 BCE-180 CE), and then spiraled into chaos from 211 to 476 CE. The Pax Romana represented an era of both political stability and moral decay. The era of chaos that followed was an age of social, economic, and political disintegration called “the fall of Rome,” a gradual decline that the Romans seemed able to delay but powerless to stop (see chapter 11). Rome therefore proved fertile ground for Christianity, a faith whose rise accompanied this growing sense of moral decay in the Western imagination.

As seen earlier in this chapter, the failure of Roman citizenship followed a pattern previously established by the Greeks. Just as Athens, Sparta, and Thebes had each grown beyond the limits of what its citizens could command by force during the Peloponnesian Wars (431-338 BCE), SO Rome had expanded beyond the limits of what its form of citizenship could control. Roman socii status had allowed Rome to win its wars in Italy and had placed it in contact with Carthage by 265 BCE. Yet in Carthage, Rome found an enemy it could not assimilate. Furthermore, Rome’s victories over the Carthaginians in three extremely difficult wars (264-241 BCE, 218-201 BCE, and 149-146 BCE) saw the Romans acquiring an enormous empire too quickly.

Accordingly, the command of so many subject people undermined the civic virtue that lay at the heart of Roman citizenship, and, just like that of Athens, Sparta, and Thebes, the internal design of Rome began to erode under pressure from the amoral political principle that “might makes right.” The consequences of such vast riches flowing into the Roman system caused its people to choke on their own wealth, initiating a greedy war policy that split the bonds holding the patricians, plebeians, and socii together. The fractures in Rome’s politics embroiled the Roman republic in a civil war that lasted 102 years (133-31 BCE), destroyed the real meaning of citizenship, and led to the rule of the principate.

Since the Romans had produced no philosophers of their own who could equal those of classical Greece, they became enamored of the Greek vision of a transcendental realm beyond everyday life.

Nonetheless, just as the decline of Greece inspired the valuable philosophies developed by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, the corruption of their own world enhanced for Romans the beauty, goodness, truth, and reality of the transcendental realm envisioned by the Socratic philosophers. Since the Romans had produced no philosophers of their own who could equal those of classical Greece, they became enamored of the Greek vision of a transcendental realm beyond everyday life. Thus, the Romans became consumers of the Greek worldview and merely added their own vision to the maturing Platonic concept of logos (see chapter 8). Hence, even though citizenship had failed in both Rome and Greece, the standards of citizenship found in Socratic thought remained an ideal for the West to admire.

Romans consumed Greek philosophy in three forms: Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Neo-Platonism. As mentioned in chapter 8, Stoicism originated with a second Greek philosopher named Zeno (334-262 BCE); do not confuse him with the pre-Socratic Zeno (490 to 430 BCE), who generated his theories while speaking from the so-called painted colonnade of Athens, the Stoa Poikile. His followers, the Stoics, or those who followed the ideas developed on the painted colonnade, carried the vision of objective reason conceived by the Socratics to such an extreme that they tried to withdraw from the physical world of passion and pleasure as much as possible. Far more popular than their Epicurean rivals (see below), the Stoics distanced themselves from the corruption of daily life through a detachment that protected them from pleasure as well as pain. The serenity they hoped to achieve was supposed to help them function effectively in public life, a public life that did not include real citizenship. The Stoics therefore believed that by achieving a state of apatheia (apathy), they could carry out their duty to other human beings through humanitarian and pacifist behavior. They hoped in this fashion to bring the divine cosmic order that governed the universe to earth, even though they were personally powerless to shape public events.

Also mentioned in chapter 8, the antithesis of Stoicism, Epicureanism, was the product of a Greek thinker named Epicurus (341-270 BCE) who abandoned the Socratic vision of the transcendental to go to the opposite extreme and restore a pre-Socratic materialism. Building on the atomic theory of Leucippus and Democritus (see chapter 7), Epicurus developed a philosophy that argued change and growth resulted from the arrangement and rearrangement of the tiny particles alone. Rejecting any role for transcendental determinism in change, Epicurus believed that all things were merely atoms going through physical transformations set in motion by their own material properties. The universe functioned on physical principles only; the gods existed but were indifferent to humanity. According to Epicurus, the absence of an eternal reward and the lack of an immortal soul made each human a mere combination of atoms; life was merely an organization of matter in a universe filled only with more matter. Therefore, one should enjoy life as much as possible by making those choices that prolonged one’s material existence as long as conceivable. The ideal state for the Epicurean was ataraxia (a withdrawal from politics, the marketplace, romantic love, and any form of stress that could upset one’s atoms). A private life of serenity achieved through thought, mild exercise, and good food and wine represented the best that human beings could hope to achieve.

Independent of the Stoics and Epicureans, Plotinus (204–270 CE) revived the metaphysics of Plato in a school of thought called Neo-Platonism. Plotinus transformed logos into “the One,” i.e., a conscious universal entity that existed apart from and was superior to all events in the world, the monotheistic force mentioned in chapter 8. Accordingly, the One constituted “true Being” the total, unitary, and simple existence that came before all other things. Reality itself was a series of descending levels, such as Intelligence, Soul, and Substance, that flowed from the highest state of existence (the One) to all other lower forms of being. Thus, the One generated Intelligence and Soul as eternal stages of the real (actuality) prior to mixing with matter to form Substance. Intelligence and Soul functioned as the second divinities (deuteros theos) or “son” to the “Father,” The One. While, the One remained unaffected by anything other than its own existence, Intelligence and Soul closed the gap between transcendental perfection and our chaotic material existence.

In the human world, the One produced inferior forms of itself. The first was Intelligence. Intelligence emerged from the One to operate as a transcendental “simultaneity,” a Being that existed at the same time as all other things but stood apart from them, as the source of the Platonic forms. The second aspect, the Soul, generated conditions of time and received the Platonic forms as reasoned principles of existence from the Intelligence, which now functioned as the logoi (the forms, words, and speech that make all things). The third aspect, Substance, occupied the three-dimensional world around us as the Soul projected itself into a negative field called “matter.” Matter had no positive existence in itself; rather, it was simply the medium that received the logical impressions made by the Soul. By itself, matter was evil in the sense that it corrupted the transcendental perfection of the logoi in generating Substance. Together Intelligence, Soul, and Substance linked the One with the material world, and the corruption of matter became synonymous with the depravity of physical existence that filled the world with decay and error. Hence, like the Socratics, Plotinus tried to integrate everything within the One but ended with a dichotomy between good and evil, form and matter, as part of everyday existence.

Neo-Platonism diffused into the Roman world even as the nomads invaded Rome, destroying its civilization. The philosophy increasingly took on the features of magic and religion. At the end of the Roman principate, one philosopher, St. Augustine (354–430 CE), the bishop of the North African city of Hippo, bridged the gap between Neo-Platonism and religion by infusing the new universal faith, Christianity (see below), with its most enduring theology. As St. Augustine wrote his City of God, the fall of Rome, the corrupt “City of Man,” represented a necessary step in creating the Christian Church, or the “City of God.” The City of Man had served its purpose by offering a unified political empire in which Jesus could do his work. So once the Christian Church, the product of Christ’s message, had taken firm root within the Roman empire, Rome’s usefulness ended. Now the divine plan called for the dawning of a new age with the “City of God,” the Christian Church; this new age would spread the “true faith” beyond the boundaries of the fallen Roman empire into the entire world. St. Augustine emphasized the transcendental spirit of the Church over the corruption of the body as represented by Rome, arguing that the infinite potential of Christianity exceeded all material limits. Thus, St. Augustine maintained the material and spiritual duality of Neo-Platonism, a well-established problem of Western philosophy generated by Socratic thought, in Christian theology.

Christianity began in Palestine, a place where the Jews eagerly awaited the arrival of the Messiah, their promised deliverer. Who this Messiah might be, how he would appear, and how he would act, no one knew. One Jewish sect called the Pharisees expected a political leader who would rescue the Jews from the grip of Rome and reconstitute Jewish law. Another sect called the Zealots waited for a military leader who would lead a victorious army against Rome and overthrow its alien rule to establish a new Jewish state. A third sect called the Essenes sought a spiritual leader who would guide them in the repentance of their sins and create a means to experience a mystical union between humanity and God. Of these differing sects, Jesus—the man some would acclaim as the Messiah—was more clearly aligned with the humble, peaceful, and spiritual goals of the Essenes than the political or military objectives of the Pharisees and Zealots.

The oldest surviving Christian mosaic and possibly the earliest rendering of Jesus Christ. In this mosaic at the Tomb of Julii, located in the catacombs under St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, Jesus (identified by the grapevines and halo) is portrayed as Sol Invictus with attributes of Apollo and Dionysus. He is shown driving a chariot of horses across the sky and carrying a blue orb (the world).

Evidence of the existence of Jesus comes from the Gospels found in the New Testament. These four accounts concerning Jesus, the kingdom of God, and salvation, however, bear witness to the faith of their authors rather than providing accurate historical records. The Gospels blend the way Jesus came into the world with a powerful message of redemption that obscures a clear picture of who Jesus really was. All that can be said with accuracy is that he was born in Judaea during the reign of Octavius Caesar (Augustus); as a Jew, he preached in the tradition of the prophets and was the most effective rabbi of his day; he railed against sin and worldly concerns; and he offered access to a heavenly realm for the righteous. His popularity among the poor caused suspicion among the rich, and his criticism of the religious practices at the temple in Jerusalem provoked the resentment of the religious establishment. The Roman procurator (governor) of Judaea, Pontius Pilate, condemned Jesus as a dangerous revolutionary and subjected him to crucifixion sometime between 30 and 33 CE. His followers, however, believed that he was resurrected three days after his burial, an event that became the critical element in the new faith he generated.

More enduring than the story of Jesus was his ministry. He established his key religious themes sometime between 25 and 33 CE. These themes included the following: that God is the Father of all humanity; that the only way to the Father was through his son (Jesus); that we all should obey the golden rule (do unto others as we would have them do unto us); that every one of us is his or her brother or sister’s keeper; that we should forgive those who trespass against us; that we should be forthright in our speech and actions and avoid hypocrisy, lies, and misdeeds; and, finally, that we should concentrate on our faith in God’s infinite love for us and not become hypnotized by ceremony or ritual. Jesus furthermore announced that the end of the world was at hand and, therefore, that we should free ourselves of sin in preparation for Judgment Day. Jesus concluded with the promise of the resurrection of the dead, which would establish the kingdom of heaven for all the righteous.

The crucifixion of Jesus approximately three years after he began his ministry marked the critical moment for his followers at the beginning of the Christian religion. Stories of the resurrection of Jesus circulated among his followers, and the faithful became energized by a new confidence in his holiness, believing that he was, indeed, the hoped-for Messiah, the son of God and the savior of humankind. With their courage restored, the core group known as his apostles began to venture out and spread the “good news” of humanity’s potential salvation. The “good news” itself, or the gospels, was a compilation of the apostles’ memories of the deeds and teachings of Jesus.

The four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John brought word of Jesus’ ministry to the Greco-Roman world. Written between thirty and seventy years after his death, the gospels bore witness to the passion of Christ (Greek for the anointed one) as the son of God. The message provided by these four documents of faith was consistent with the image of Jesus as both a prophet and the son of God. Despite the legends that might have contaminated the historical accuracy of these accounts of Jesus himself, these gospels became the cornerstone of the new faith of Christianity.

The fourth gospel in particular reveals that the beginning of a union between Greek philosophy and Christianity had already begun. Here the author, the apostle John, opened his account of the good news with this sentence: “In the beginning there was the word, and the word was with God, and word was God.” In koine Greek, the common language of the eastern half of the Roman empire and the language in which John wrote, the term for word was logos. As mentioned in this chapter and chapter 8, in Greek logos had a far greater meaning than merely “word” or speech; logos also meant reason, logic, or the logoi of the Neo-Platonists. In short, word, speech, and logic were all part of the same concept and could not be separated from one another.

Since reason and logic in Greek philosophy identified the transcendental essences behind all existence, the use of logos to name God linked the Greek realm of eternal forms with the Hebrew vision of ethical monotheism. Thus, to these early Christians, most of whom were converted Jews, logos slowly became a conceptual connection between transcendental reason and God’s divine plan for the universe. Also, Jesus became the central player in this plan; when his message diffused into the Greco-Roman world, Greek philosophy became part of a heuristic (aid in learning) device to develop a theology that communicated the ministry of Jesus to the pagans (nonbelievers).

Prior to the gospels spreading the news of Jesus, Saul of Tarsus (later St. Paul, ca. 10–67 CE) broadened the new faiths potential to embrace the entire world. Paul was not born in Palestine but was a Jew who lived in Tarsus, a Cilician city located near the frontier between modern-day Turkey and Syria. Originally a Pharisee, a person who insisted on strict adherence to Jewish law, and a persecutor of Christians, Paul had his first known contact with the followers of Jesus at the martyrdom of St. Stephen, the first Christian to die for his faith. Then Paul received a commission from the chief priest in Jerusalem to travel to Damascus to suppress Christianity. But on the road to Damascus in 35 CE, Paul had an intense religious experience, a vision that converted him to the new faith and turned him into a devout evangelist. It was through Paul’s ministry that Christianity left the confines of Judaism and spread among the gentiles (all non-Jewish people) of the Roman world.

Denying that Jesus was merely the redeemer of the Jews, Paul made Christianity into a universal religion. He did so by placing an emphasis on the ideas of Jesus as the “Christ,” or “the anointed one” in koine Greek. According to Paul, Jesus was a god-man, the deuteros theos, sent to Earth by his divine father to die for all of humanity’s sins. Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross ushered in a new age in which Jewish ceremony and law ceased to be the primary means of achieving righteousness; now, humanity could achieve salvation by having faith in God’s infinite mercy. Paul argued that if God was willing to sacrifice his own son for the sinful people who walked the Earth, then his mercy, as well as love for humanity, had no bounds. All each person had to do was acknowledge Jesus as the savior and join a growing community of the faithful.

Since reason and logic in Greek philosophy identified the transcendental essences behind all existence, the use of logos to name God linked the Greek realm of eternal forms with the Hebrew vision of ethical monotheism. Thus, to these early Christians, most of whom were converted Jews, logos slowly became a conceptual connection between transcendental reason and God’s divine plan for the universe.

Thus while Jesus had proclaimed the imminent coming of the Kingdom of God, Paul’s religious message became the means to define the gentle ceremonies that marked one’s faith in God. Long after Paul’s death as a Christian martyr in 67 CE, when he and the apostle Peter became victims of persecution by the Roman emperor Nero, the ceremonies Paul instituted eventually became the sacraments of the Church as it grew in size and complexity over the years. These ceremonies would celebrate Jesus’s message and bring the believer ever closer to Christ. Yet ironically, the Church that served as the vehicle for bringing Christianity to the world also came to dominate the Western imagination as a powerful institution. This created a paradoxical voice in the Church: as the Church created an orthodoxy to define Christianity, it also contradicted Paul’s original message that one could achieve salvation through faith alone. Such a paradox—the conflict between an emerging orthodoxy, or a standardized belief, and individual or personal faith—would eventually cause major problems for the Church in the modern age (during the Reformation, 1517–1648 CE (chapter 18).

Christian theologian Origen of Alexandria (185–254 CE).

Origen was among the first Christian thinkers to produce a systematic theology for the Church. Though some of his ideas were later declared heretical, he helped lay the foundation for the blending of Greek and Christian beliefs.

Meanwhile, in the second and third centuries CE, the growing complexity in the expanding Christian community resulted in questions about God, Jesus, and salvation. Each question generated a debate in which the different religious opinions about God, Jesus, and salvation were resolved by introducing Greek philosophy and logic into a new discipline called theology. Theology developed the Christian understanding of God and his son, Jesus Christ, and generated the orthodoxy that received support from a growing Church hierarchy. At the same time, the theological resolutions of these questions slowly melded logos with Christianity as both matured within the boundaries of the Church.

Men like Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150–215 CE) and his most famous student, Origen (185–253 CE), began this process of blending Greek philosophy with Christianity to create a nascent form of theology. Clement of Alexandria was among the first to formulate a relationship between Plato’s vision of the universe and Jesus as the son of God. Clement espoused the belief that philosophy among the pagan Greeks was part of the divine plan because it served as a pedagogical preparation for the coming of Christ. He argued that Greek philosophy had created the proper mental constructs that allowed people to acquire a clear understanding of God and his son. He also argued that the philosophers of his day had to rise above their pagan heritage and perfect their knowledge of reality through the revealed truth of Christ.

Like Clement, Origen was enthusiastic about Platonic concepts and borrowed heavily from Greek philosophy. Origen was among the first Christian thinkers to produce a systematic theology for the Church. Though some of his ideas were later declared heretical, he helped lay the foundation for the blending of Greek and Christian beliefs. The most famous of his views, which was eventually rejected by the Church, was apocatastasis (Greek for “re-establishment”) or the universal salvation and restoration of all creation by God. Origen used the term apocatastasis to refer to the return of all souls to God and heaven, including those condemned by God for their sins. Origen believed that, given his omnipotent and eternal nature, God would triumph over evil and all souls would eventually come to embrace him. Thus, even those souls who had willfully violated God’s laws would eventually see the errors of their ways and thus be saved. Ultimately, everyone in the universe was destined to seek the bliss offered by the pure goodness, beauty, truth, and reality of God. Yet such a view eliminated the threat of sin by reducing its punishment from eternal damnation to a lengthy but finite penance. As a result, the early Church rejected apocatastasis.

Between the third and fifth centuries CE, as the Church continued to grow and became legal under the Roman emperor Constantine (ca. 288–337 CE), its size and complexity led to increasing disputes over the nature of Jesus and his role in the divine plan. These disputes refined Christian orthodoxy and condemned heresy, i.e., ideas that the Church declared to be officially in error. Among these early heresies were those proclaimed by the Donatists (ca. 350 CE), who posited that sinners, once having sinned, might receive God’s forgiveness but could not be re-embraced by the Church without causing contamination. Another heresy, Monophysitism (ca. 450 CE), declared that Jesus was not a God-man but God pure and simple. Hence, Christ only appeared to have died on the cross; in reality he had ascended directly to heaven as pure, uncorrupted divinity. The single most important heresy, however, was the one started by Arius (ca. 250–336 CE).

Arius, a Libyan theologian who preached in Alexandria, declared Christ different from God since God had infinite existence before and after the beginning of time, while the life of Christ had begun at a finite moment in time. As a result, the being of Jesus was not identical to that of his Father, but only similar to it (homoiousios). But if Jesus existed in a state of being less than God, his infinite divinity then came into question. To limit Christ’s infinite divinity was to diminish his role in human history relative to God and lessen the quality of the mercy obtained by his sacrifice on the cross.

Athanasius, a powerful theologian who served as the Patriarch of Alexandria (328–373 CE), as one of four principal bishops within the empire, he argued the opposite, that Christ and God were the same (homoousios). And since Christ and God shared the same Being, Jesus represented God’s infinite mercy in the form of self-sacrifice. Thus, the death of Jesus through crucifixion was a sign of God’s divine plan for the salvation of humanity. Athanasius felt that Arius’ challenge to Christ’s nature threatened the very foundations of salvation itself and thus the Church.

Resolution to this debate came at the Nicene Council, which launched the idea of the Trinity. The Nicene Creed emerged from the first Church Council, the Council of Nicaea, a city in Asia Minor southwest of Constantinople. In 325 CE, the emperor Constantine had called the council to deal specifically with Arius, and in doing so the council wove the concept of God and logos together into a synthesis that reached maturity in the fifth century CE. The Nicene Creed declared Christ to be God’s equal because Jesus was merely God conceiving of himself when he created his son. Accordingly, since God conceived of Jesus before Christ’s birth, then the idea (logos) of the son preceded the son himself. In addition, since the idea was a transcendental form that took precedence over any material manifestation of itself, then the infinite nature of Jesus preceded his birth as a God-man. Thus, Christ, the historical son, became a material expression of pure, infinite Being as expressed in the eternity of God’s imagination. Consequently, the divinity of the son was the same as the divinity of the Father because both belonged in the same existence, a concept named consubstantiation.

A page from Saint Augustine’s City of God.

By the fourth or fifth centuries CE, the Greco-Hebrew-Christian synthesis achieved its complete form in St. Augustine’s City of God. Mentioned above, this work bridged the gap between the ancient world and the Middle Ages to become the first medieval document that combined Neo-Platonism, Christian, and Hebrew ideas with the Church (the City of God). In it, God’s function crystallized in a union with the Greek logos to join ethical monotheism with Plato’s Universal Soul, Aristotle’s final cause and Prime Mover, and Plotinus’s the One. For St. Augustine, failure to live a good Christian life was akin to nurturing the body (our corrupt matter) while ignoring the soul (our pure form). When such a person died, only the body (matter) remained on Earth, for the soul had withered. These material remains soon became decaying matter without form, beauty, truth, or reality. Those whose souls had died because they never embraced Jesus as their savior would never experience God in heaven, which lay at the edge of a finite, geocentric universe. They would never understand pure reality, truth, beauty, and goodness and would never know God. This became the ultimate punishment, the essence of what became known as hell.

St. Augustine wrote his work because he knew the fall of Rome was inevitable. The Visigoths had captured the city in 409 CE, and other nomadic tribes were entering the empire in seemingly endless waves (see chapter 11). The fall of Rome was at hand. To explain why God would inflict barbarians upon the civilized, sacred world required the vision of a new age. And for St. Augustine, this explanation came with ease: the “City of Man” was the body of society and doomed to perish; its end could only signal the rise of the “City of God.” The fall of Rome, therefore, marked the beginning of a new era: the age of Christ.

St. Augustine assigned a divine purpose to the shift from the ancient to the medieval world. His City of God synthesized the Hebrew, Greek, and Christian senses of reality to make every human experience a direct lesson from God and all souls equal to the task of salvation. The destruction visited upon the Roman world was merely part of the divine plan, just as the fall of Israel and Judah had prepared the Hebrews for the next age in their evolution (chapter 2). The actual fall of Rome must wait, however, until the collapse of the ancient Eurasian world is fully discussed in chapter 11.

Beard, Mary, and Michael H. Crawford, Rome in the Late Republic, 2nd ed. (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1985).

Boardman, John, Jasper Griffin, and Oswyn Murray, The Oxford History of the Roman World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991).

Boren, Henry C., Roman Society, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina; Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Heath, 1977).

Cary, M., and H. H. Scullard, A History of Rome Down to the Reign of Constantine, 3rd ed. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975).

Cochrane, C. M., Christianity and Classical Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957).

D’Arms, John H., Commerce and Social Standing in Ancient Rome (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981).

Frende, William H.C., The Rise of Christianity (London: Darton, Longman, and Todd, 1984).

Garnsey, P., and R. Sailer, The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

Kebric, Robert B., Roman People (Mountain View, Calif.: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1993).

Long, A. A., Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, and Skeptics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974).

MacMullen, Ramsay, Christianizing the Roman Empire (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1983).

Sherwin-White, A. N., The Roman Citizenship, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973).

Syme, R., The Roman Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960).

Wells, C., The Roman Empire, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984).