2

The Palazzo San Francesco

‘… and the said Duke leaves to his second son Ippolito the palace of San Francesco together with its orchards and gardens and all other appurtenances. He endows the aforementioned Don Ippolito with 13,000 scudi which he commands and desires to be granted and paid forthwith to the said Don Ippolito to the effect that the said Don Ippolito may and should furnish the said palace with all the goods and furniture necessary and appropriate to the rank of the said Duke and of the said Ippolito.’

Last will and testament of Duke Alfonso d’Este, 1533

THE PEDANTIC LANGUAGE of Duke Alfonso’s will is that of lawyers down the centuries – why use one word when two will do? But the emphasis the Duke placed on the direct relationship between rank and display is significant. Ippolito was his son; he was also Archbishop of Milan and hoped one day to become a cardinal. In his will the Duke stressed the importance of conspicuous expenditure ‘necessary and appropriate’ for his son’s position. It was to that end that he left Ippolito 13,000 scudi. This was an awful lot of money, and even the extravagant Ippolito was unable to spend it all on refurbishment.

Duke Alfonso died on 31 October 1534, aged 58, leaving his duchy to his eldest son, Ercole, and his favourite leopard to a cousin. To Ippolito he left both money and property, providing the income necessary for Ippolito to pursue a career in the Church and his goal of a cardinal’s hat. In addition to the palace, Ippolito’s rights to Belfiore were confirmed and he was given a valuable set of silver plates to ornament his credenza. He was assigned a monthly allowance, which Ercole was obliged to pay out of ducal revenues, as well as the income from the town of Brescello, the taxes raised on butchers in Reggio and on all live animals entering Ferrara (he had to share this last item with his stepmother), and agricultural estates in Fóssoli, Pomposa and the Romagna. By the end of November Ippolito’s newly painted coats-of-arms adorned the walls in each centre, announcing the change of ownership. Duke Alfonso’s death marked an important rite of passage for the 25-year-old Ippolito: financial and domestic independence. It also marks the point at which Ippolito himself begins to emerge from the accounts’ ledgers and letters preserved in the Modena archives.

The Palazzo San Francesco was a grand house, close to the old city centre. It had been built in 1485 by Ippolito’s grandfather, Ercole I, and had been home not only to his father but also to his uncles, Giulio and Ferrante, who were still imprisoned in the ducal castle. The palace was a rectangular two-storey block built around two courtyards, which opened directly on to the street (now Via Savonarola). At the back was nearly a hectare of garden. Visitors entered the larger of the two courtyards through a grand portal, flanked with fluted piers and crowned by an elegantly carved arch. A smaller arch, the tradesman’s entrance, led into the second courtyard where the stables and kitchen were located. As was the custom in Italian palaces, the main reception rooms and private apartments were all on the first floor (piano nobile), which was reached by a staircase leading up from the far side of the main courtyard. The largest room was the Great Hall. Extending the full length of the street façade, it measured 30 metres by 10 metres and was used mainly for banquets and grand entertainments. There was also a slightly smaller hall at the back of the palace, overlooking the courtyard, which was used for more intimate gatherings. Behind this hall were the private apartments, all facing the garden. The building was serviceable but the decor was old-fashioned and, given the terms of his father’s will, Ippolito decided to modernize it completely. He lost little time: just over two weeks after his father died, the builders arrived.

Ferrara, Palazzo San Francesco, garden loggia

The work took a year to complete and Ippolito did not move in until November 1535. As is the way with builders, the palace soon became uninhabitable. The courtyards were littered with heaps of sand and lime, piles of bricks, stone for the window frames, planks of wood and tiles for roofs and floors. The wells and drains were dismantled and repaired, and so was the staircase. All the rooms were redecorated, and their tiled floors relaid. New fireplaces, doors and doorframes were installed in all the important rooms. A roofer and his boy spent all summer replacing broken tiles and mending the guttering. There was scaffolding in all the main reception rooms where the painters were decorating the ceilings and Ippolito’s own rooms had gaping holes where the builders were installing new windows. The garden was also redesigned. Ippolito took on two new gardeners, one full-time employee (with a salary of 17 scudi a year, and a new pair of shoes every month) and a part-time assistant to help prepare the ground for planting – they planted 130 fruit trees that October.

|

Scudi |

Building materials and transport |

707 |

Istrian stone doors |

151 |

Wages to builders and carpenters |

711 |

Wages to painters |

184 |

Pigments and materials |

171 |

Garden plants and work |

49 |

Total |

1,973 |

The cost of modernizing the Palazzo San Francesco

Most of the money Ippolito spent on the palace went on building work. Architecture was considerably more expensive than painting and accounted for 80 per cent of the total. The Istrian stone doorways he installed in his own apartments were a particularly extravagant detail. Specially made for him in Venice, they arrived by barge in July and were installed by the men who had carved them. Ippolito was delighted with the result and presented each of the stone cutters with a pair of stockings. The biggest single project for the builders was the garden walls. These were repointed and embellished with new brick merlons, a traditional Ferrarese feature which had been revived and popularized by Duke Ercole. The walls were then decorated with frescoed landscapes, painted by a local artist, Jacomo Panizato, and two others brought in from Bologna. The total cost of this lavish garden wall came to 380 scudi, enough to pay the annual wages of ten master builders.

The teams of builders, labourers, carpenters and painters employed on the palace normally worked Monday to Saturday, dawn to dusk. There was no conventional two-week holiday, though the men were given the day off for all major Church feasts and local festivals, making a working year of about 250 days. They were hired and paid by the day – no work, no pay – and they could be laid off if there was insufficient work or, for those working outside, if the weather was bad. Pay day was Saturday, a busy afternoon for Ippolito’s bookkeeper, Jacomo Filippo Fiorini, who had to record the sum given to each of the workers, the number of days they had worked that week, what they had been working on and the rates at which they were paid.

Fiorini’s entries are somewhat impersonal but they do provide an insight into the lives of ordinary artisans in sixteenth-century Ferrara. The head of the team of painters employed to decorate the ceilings of the reception halls and those in Ippolito’s apartments was Andrea – in the accounts he was known simply as Andrea the painter (Andrea depintore). These were no ordinary ceilings but elaborate wooden affairs, studded with rosettes and inlaid with panels surrounded by several bands of moulding. Andrea and his team spent most of the year painting them with intricate floral patterns in red and gold against a dark background, and gilding the carved details of the mouldings and the rosettes. Andrea was taken on in late November 1534 and got work every week for the following twelve months. Initially it was sporadic – he and one other painter worked only eleven days before the end of the year – but it picked up in January. By February there were six men at work on the ceilings and Andrea was given a pay rise in recognition of his role as team leader. They continued to work steadily through the spring and summer, with a short break in August when they helped the painters decorating the garden walls. The garden team had been working under a large canopy to protect the frescos as they dried and to shield the artists from the fierce summer sun, but it blew down in an unexpectedly violent storm which lashed Ferrara on 12 August and ruined all the unfinished painting. Andrea might have been ill one week in early September when he only worked for a day and a half, while the rest of the team managed six days each. There were two other thin weeks in late July and early October, which affected them all. As mid-November, the date for Ippolito’s move, drew closer, work became more frenetic. During the last four weeks Andrea only had three days off and worked solidly for over two weeks, including two Sundays and the feast of All Saints (1 November).

Over the year Andrea worked a total of 224½ days and earned just over 28¼ scudi, a sum augmented by another ½ scudo which his wife received for sewing sheets for Ippolito. Compared to the cost of Ippolito’s extravagant garden walls their income was minimal, but it was enough to be able to live comfortably in Ferrara. The rent on a modest family home was about 5 scudi a year, and the standard food allowances paid to the courtiers of the ducal household, which provided half a kilo of meat and one kilo of bread per person per day, added up to less than 11 scudi a year.

![]()

During the summer, while the builders and decorators were busy on the Palazzo San Francesco, Ippolito and his brother assembled Ippolito’s new household. Like the palace, it was designed as a deliberate statement of Ippolito’s rank and prestige, and, though smaller than Duke Ercole’s entourage, it was identical in composition. It also established Ippolito at the head of his own power structure and created a new network to weave into the complex web that formed the framework of European political patronage. Ippolito’s own success would reflect directly on the members of his household: a cardinal’s cook might not earn more than that of an archbishop but he had appreciably more status. At all levels of Renaissance society the right connections mattered, and the opportunity to join the household of this ambitious young man was not one to be missed.

The sixteenth-century term for a household was a ‘family’ (famiglia), a word that meant much more then than it does now. When speaking about his ‘family’, Ippolito included all his domestic staff – the men who dressed him, prepared and served his food, made his clothes, looked after his wine and horses, ran his errands and cleaned his palace. Despite the fact that its members came from all walks of life, the household was a close-knit unit. Loyalty was expected, and in return Ippolito was generous towards his men. Apart from their wages and living expenses, he gave practical help when needed, settling debts with a pawnbroker for one, paying for the funeral of another whose widow was too poor to afford it herself. When his valet died in 1534, Ippolito gave his family regular presents of flour and clothes for the children and put up the money for one of the daughters to enter a convent. He also gave food and money to a retired member of the dining staff, ‘because he has been a faithful servant, and is poor and burdened with children’. It was not surprising that Ippolito paid a doctor’s bill after one of his stable boys had been badly kicked by a stallion, but it is a reminder of how attitudes to staff have changed to see that he also paid for a doctor to treat a monk who had been knifed by his gardener’s son.

At the beginning of 1535 Ippolito employed a staff of just twenty-two; by the end of the year he had eighty-two men on his books (there were no full-time women). This was a dramatic increase and a reminder, in case he needed it, of his new independence. The number of men employed to run his estates increased from three to ten. His household proper quadrupled in size. In addition to the valets and staff who had looked after him in his apartments in the ducal castle, and his animals at Belfiore, he now had his own courtiers, dining-room staff, cooks, footmen and squires, and even his own pages, young sons of noble families attached to his household to learn the art of court etiquette.

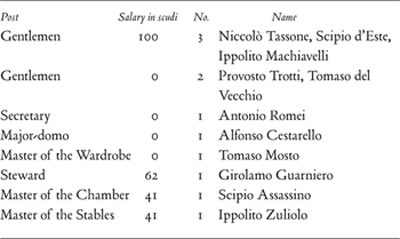

The most important members of Ippolito’s household were his courtiers: five gentlemen, a secretary and another five men who held the posts at the head of the various household departments. The gentlemen were all young, much the same age as him, and handpicked to be his closest companions, those with whom he hunted and jousted, played cards and tennis, gossiped and dined. All came from aristocratic families with close links to the ducal court. Antonio Romei, the son of a ducal courtier, had become Ippolito’s secretary in 1534. Scipio Assassino, a cousin, albeit on the wrong side of the blanket, had been Ippolito’s valet since 1527 and was now promoted to Master of the Chamber (maestro di camera). Alfonso Cestarello took the job of major-domo (maestro di casa), Girolamo Guarniero became the Steward (sescalco) and Ippolito Zuliolo was appointed as the Master of the Stables (maestro di stalla). The post of Master of the Wardrobe (guardarobiero), however, posed a problem. In Ferrara this job was traditionally combined with that of treasurer and, since 1530, the two roles had been undertaken by Ippolito’s bookkeeper, Jacomo Filippo Fiorini. He was good at his job but his father was an artisan, and he himself had trained as a painter before starting to work for Ippolito. Class mattered at the courts of sixteenth-century Europe, and Fiorini did not have the right social background. Ippolito therefore appointed Fiorini as his chief factor in Ferrara, to take charge of the overall management of his estates, and gave the job of Master of the Wardrobe to Tomaso Mosto, the brother of one of Ercole II’s valets.

Tomaso Mosto, Master of the Wardrobe

Courtiers’ salaries

All the courtiers received expenses for their servants as well as hay and straw for their horses, but their remuneration varied considerably. Five of them were not in the salary lists at all. They had opted for careers in the Church and had joined Ippolito’s household in the expectation of benefiting as their patron advanced up the clerical ladder. Cestarello already had a canonicate at Bondeno, one of Ippolito’s benefices near Ferrara. Mosto and Trotti both held benefices attached to the cathedral of Ferrara: Trotti was Provost there and was known in the accounts ledgers as Provosto Trotti.

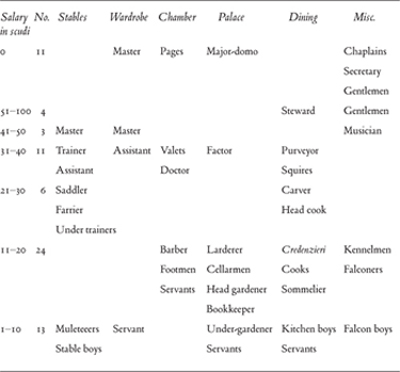

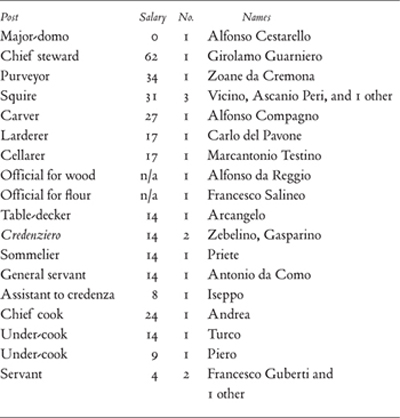

Below these courtiers came the rest of the household, their status more precisely graded by salaries and perks (see table overleaf). Neither of the two chaplains received salaries, but they did receive expenses and shared a house rented for them by Ippolito.

It was not just salaries and perks that identified rank in the household but also the standard of accommodation provided in the Palazzo San Francesco. The size and location of each man’s room (or rooms), whether his windows had glass in them or were just covered with waxed cloth, and the type of bedding he was given, all had a real impact on their lives. The courtiers lived in considerable comfort. They were housed on the first floor, each with their own rooms opening off the spacious balconies that flanked the upper storey of the main courtyard. The rooms had been redecorated for their new occupants and all had glass windows. There were fireplaces for warmth in winter, and the air that circulated through the shaded loggias lessened the stifling heat of summer. Assassino’s salary may not have been very high but his room was smart enough to be allocated to the French ambassador when he visited Ferrara in April 1537. The other two valets shared a large room in the same part of the palace, as did the three squires.

Ippolito’s household in 1536

Further down the ranks life was less comfortable. The kitchen staff lived in the side wing of the palace, sharing rooms which looked out on to the smaller courtyard that served the kitchen and the stables. Their cloth windows could not have provided much protection from the weather, nor from the smells rising from below. The five footmen had to share a windowless room in the attic, or, as Fiorini vividly recorded in his ledger, ‘under the tiles’, which must have been unpleasant in both winter and summer. Perhaps the most telling nuance in distinguishing status was the quality of the mattresses and sheets Ippolito supplied for all the men living in the palace. His own sheets, made of the finest linen, cost three times as much as the rough cloth bought for the household beds. Fiorini took charge of organizing mattresses for the entire household. He bought three different kinds of wool and ticking, and he commissioned a mattress-maker to make up the mattresses in various different combinations of wool and weights. The bill for forty-two mattresses, which Fiorini paid in June, listed the following:

No. |

Quality of wool |

Weight (in kg) |

5 |

Cheap |

10 |

15 |

Medium |

14 |

3 |

Medium |

15½ |

1 |

Medium |

16 |

14 |

Medium |

17 |

2 |

Expensive |

19 |

2 |

Expensive |

22 |

Mattresses

The best pair were for Ippolito himself, made of fine lambswool. Fiorini did not allocate any of the others in his ledger, though it is likely that the five cheap mattresses were for the five footmen in the attics. The stable boys had to make do with shared straw palliasses in the stables.

The stables were in a two-storey building immediately on the right after the arched entrance into the second courtyard, with stalls for the horses, tack rooms, storerooms for Ippolito’s elaborate caparisons and harnesses, and workshops for the saddler and farrier. They were large, perhaps 20 metres by 10, and had been substantially renovated during the summer of 1535 with new brick floors, a tiled roof and six cloth windows. They had their own well and drains, and they were lit with candles and with glass lanterns fuelled by oil supplied by the palace larder. During the summer of 1535 they had also been newly furnished with quantities of sieves, forks and heavy metal buckets, as well as wooden feed chests secured with heavy padlocks.

The stables employed about twenty men, though the total varied, depending on the number of stable boys. In January 1536 there were eleven on the books, as well as skilled technicians such as the saddler, the farrier and four trainers. This was also the department with the widest cross-section of social backgrounds, from the aristocratic Zuliolo down to the lads. A stable boy’s life was hard manual labour and involved mucking out stalls, measuring feed, harnessing the horses when they were needed and washing them down when they were returned after a long day’s hunting. The lads earned pitifully low salaries, hardly a living wage – 5 scudi a year, which would have bought them just two capons a week, or two small pigs a year – though at least they had somewhere to sleep. Nor did they eat in the palace like the rest of the stables’ staff. Instead they received a daily allowance of a hundredth of a scudo, which would buy them half a kilo of cheap beef or 800 grammes of bread each day. Unsurprisingly, given their physical and social isolation, they did not have the same sense of loyalty as other members of the household. Theft was a problem – hence the heavy padlocks on the feed chests. Most were casual labourers who just wanted to earn a few lire before moving on, and as a result the turnover of stable boys was markedly higher than that in any other department. Few of them stayed as long as a year, and one left after only six days.

The basic diet fed to the horses and mules consisted of hay, millet and bran, though barley was also given to weak foals and to the stallions when they were covering the mares. Foaling and covering were annual events which required a lot of extra work for the stable boys who, in addition to their normal day’s labour, had to stay up most of the night as well: larger than usual quantities of tallow candles were taken from the larder so that they could keep an eye on the mares and stallions, and they were rewarded with salamis, also from Ippolito’s larder. Organizing fodder for these animals, stabled in the centre of town, was a major undertaking. The gardener at the Palazzo San Francesco was paid each year for cutting the grass to make hay, but this provided only a tiny proportion of the quantity needed. Most of the hay, straw and grain came from Ippolito’s estates at Bondeno and Codigoro, transported by barge along the Po to the wharves below the Via Grande from where hired carters delivered it, either to the barns built in the gardens at Belfiore or to Ippolito’s granary. In preparation for the move to the palace 160 cartloads of hay were delivered during the first two weeks of June, and 246 cartloads of straw arrived in October.

Zuliolo, Ippolito’s Master of the Stables, had little professional expertise to offer and his post was largely a sinecure. It was his assistant, Jacomo Panizato, who took charge of the funds. Fiorini gave him regular advances of cash every week, 50 scudi or so at a time, to cover the stables’ expenses, and Panizato had to account for every penny, recording each item in his own ledger. This job required someone both literate and trustworthy, though not necessarily skilled in looking after animals. Nevertheless, Panizato’s appointment was unusual. He was a painter by training and had spent the summer of 1535 working at the palace, producing ornamental panels for ceilings in several rooms and painting landscapes on the garden walls. Perhaps there was not enough work for him in Ferrara, or perhaps he was bored of painting, but the career move certainly improved his social status. By 1538 he was no longer referred to in the account books as an artisan (maestro) but was described as Messer, the title given to men of standing, though below the rank of noble (Magnifico).

The horses themselves were the responsibility of Pierantonio, the chief trainer, who had been with the household since 1530. He earned a salary of 34 scudi a year, with expenses for himself, a servant and a horse, and Ippolito rented a house for his wife Catelina and their family. Pierantonio also had a room above the stables which had glass windows, a mark of the importance of his job. It was Pierantonio who bought all Ippolito’s horses and mules, a task which frequently took him away from Ferrara, to nearby cities such as Mantua and Bologna, and also to places further afield such as Aquileia, north of Venice, or across the Apennines to Florence and even Naples. Horses and mules were the only forms of transport in sixteenth-century Europe. Ippolito had an impressive number of horses and mules, all named. The mounts he himself used for travelling, hunting, jousting and ceremonial occasions were all thoroughbreds, but he also owned ordinary hacks for the use of his household, as well as carthorses and pack mules. Pierantonio could buy an ordinary hack for as little as 5 or 6 scudi, but a good mount could cost up to 40 scudi. Surprisingly, mules were far more expensive. A cheap pack mule cost over 30 scudi, and a good one as much as 80 scudi.

Pierantonio was responsible for buying and mending all the equipment needed for his charges – bits, stirrups, whips and harnesses – and these he ordered from tradesmen across Ferrara. His job also involved veterinary skills. He took candles from the larder to treat cracked hooves and bought various compounds from the apothecary’s shop which he mixed to make medicines, salves and poultices for more serious conditions. The apothecary also sold a special oil to treat scorpion bites. Among the compounds Pierantonio used regularly to make his salves were vinegar, turpentine, pig fat, incense, mastic and even mercury, as well as verdigris, Armenian bole (a reddish clay) and a bright red resin known as dragon’s blood. These last three items were also used by the painters to gild the ceilings inside the palace and were bought in large quantities to be stored in the wardrobe.

Inside the palace the man with the greatest responsibility was probably Tomaso Mosto, the new Master of the Wardrobe. With the help of his two assistants and a bookkeeper, he was in charge of the purchase, manufacture, laundering, storage and repair of Ippolito’s clothes. This was no small task. Ippolito’s collection of clothes was huge: in 1535 Mosto had charge of over 350 items. Depending on what Ippolito was doing each day, Mosto might have to prepare as many as five outfits to suit the diary. All the laundry was done by hand, and many items also needed starching with sugar. Mosto bought all the materials for new outfits and commissioned tailors to make up the garments. The embroidery on Ippolito’s shirts was done by nuns in various convents in Ferrara. Mosto particularly favoured a Sister Serafina at San Gabriele: she might have been Middle Eastern in origin (she was once described as persiana in the ledgers) and she was paid 1½ to 3 scudi for each shirt (the money, of course, went to the convent).

The responsibilities of the wardrobe, however, extended far beyond the care of Ippolito’s clothes. Mosto had to organize the special outfits worn by the valets, footmen and pages when they escorted Ippolito in public. He looked after Ippolito’s armour and weapons, his perfumes, jewels, silver, books and other valuables, as well as the palace furnishings, notably the tapestries, paintings and bedhangings, and the huge quantities of table and bed linen used by the household.

Stocking the wardrobe at the Palazzo San Francesco was an enormous undertaking and it was shared by Mosto and Fiorini. During January and February 1535, Mosto spent over 240 scudi on huge quantities of sheets, tablecloths and napkins for the palace. He bought most ready-made in shops in Ferrara, especially from two Jewish second-hand clothes dealers: Jacob, who specialized in cheap sheets and tablecloths, both new and used, and Isaac, who stocked better-quality linen. It was Isaac who supplied Ippolito’s new goose-feather bed for 22 scudi (he threw in ten pillows for free). The range in quality was considerable. Ten fine linen napkins for Ippolito cost Mosto 3 scudi, the same sum as he paid for twenty-five plain household ones. He also had to commission people to sew and hem. Much of this work went to women connected with the household. Malgarita, the wife of one of Ippolito’s falconers, sewed four dozen napkins and eight household sheets for ½ scudo (just under two weeks’ wages for her husband), and the task of sewing Ippolito’s own sheets was given to Catelina, the wife of Andrea the painter.

Meanwhile, Fiorini was sent off to Venice in February (leaving Mosto to keep the books) with an enormous shopping list – mainly equipment for the kitchen and dining-rooms, but also candlesticks, fire-irons, colours for the painters at work on the palace ceilings, sugar for the wardrobe, glass window panes and the loads of wool that he needed to make mattresses for the household. This was quite a task and he was away from Ferrara for almost a month. Everything had to be bought from specialist suppliers. He commissioned various coppersmiths, tinsmiths and pewterers to make each individual item of kitchen and dining equipment according to his specifications, and paid blacksmiths to add iron handles. He had to hire a boat to go out to Murano to order the window panes and glasses. The bill for this shopping expedition came to over 400 scudi, and it cost another 6 scudi to get the goods shipped back to Ferrara. Why travel all the way to Venice, a two-day journey, when Ferrara was amply supplied with shops? There were two reasons: quality and price. The city – aptly described by one historian recently as the Bloomingdales of Renaissance Italy – was famous then, as now, for its glass, and for the high quality of the goods imported by Venetian merchants from overseas. In Venice Ippolito could buy the best glass in Europe, the best pigments from the Middle East and the best sugar from Madeira. The sheer size of the Venetian market also meant competitive prices on cheaper goods. The metalware that Fiorini commissioned was 30 per cent cheaper than it would have been in Ferrara.

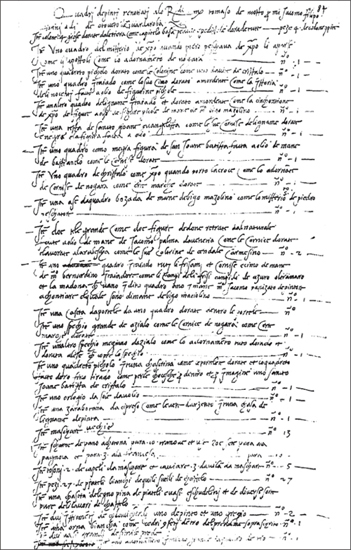

Mosto and Fiorini also shared the onerous task of drawing up an inventory of all Ippolito’s possessions prior to the move into the Palazzo San Francesco. It took most of October and it cannot have been easy for Fiorini. As he recorded in his ledger at the start of each day’s work, it marked the point at which he handed over responsibility to the new Master of the Wardrobe. Ippolito had accumulated an astonishing number of possessions in his twenty-six years. The clothes alone took the best part of four days to itemize, the armour and weapons another day. The inventory listed the entire furnishings of the palace and ran to nearly a thousand entries. Some of these were individual items but many were multiple. It must have been tedious work. One wonders how many times the two men had to count 468 shoelaces (Ippolito owned 611 in all), 215 antique coins, 199 rosary beads, 102 handkerchiefs or 70 curtain rings. Each of the 116 bolts of cloth had to be unrolled, measured with a wooden rod and then carefully rolled up again, while Fiorini recorded the details in his ledger. Averaging five minutes a roll, this would have taken them the best part of ten hours. The velvets, damasks, silks and satins for Ippolito’s clothes, and the lengths of cheap cotton and canvas for household use – a total length of 1,500 metres and ranging from a 30-centimetre strip of red velvet to 400 metres of the blue cotton cloth that was used to line Ippolito’s tapestries – all were treated with the same care and measured with the same precision. For Fiorini and the assistants, there must have been some sensual pleasure in seeing and handling these luxury fabrics, but the same could not have been true for the table linen and sheets. There were no standard sizes for these items. Each of the 112 sheets and 298 napkins and tablecloths also had to be measured, length and width, before being refolded and replaced, while Fiorini entered the size and material of each item in his ledger. And, although Mosto could go home at the end of the day, Fiorini still had to do his new job as Ippolito’s factor. Saturday, 2 October, must have been particularly gruelling. After spending the morning at the ducal castle itemizing the candelabra and fire-irons, and recording the details of 99 tablecloths and napkins, Fiorini returned to his office at the Palazzo San Francesco to pay the week’s bills and wages, filling in another two pages in his ledger.

A page from the inventory compiled by Fiorini and Mosto in October 1535. Listed on it are Ippolito’s paintings, mirrors, clocks and clavichords

The move took several weeks. All Ippolito’s possessions had to be transported from the ducal castle, a ten-minute walk away from the palace. Fiorini hired a carter in early October to move the heavy furniture (the first items he and Mosto had inventoried) and a porter was taken on to help move the lighter stuff. The palace needed extensive cleaning before the textiles arrived.

The builders had done a magnificent job. The grand reception halls and the rooms of Ippolito’s apartments looked splendid. There was glass in all the windows, new stone fireplaces with carved and gilded mantelpieces, and polished walnut doors set in carved Istrian marble door frames. The heavy wooden ceilings were now brightly painted, their mouldings and rosettes glittering with gold. On the ceiling of the Great Hall were the gilded arms of the Duke and Duchess, and carved eagles, Ippolito’s personal device. His own coat-of-arms, picked out in gold and silver, sparkled over the fireplace in the smaller hall at the back of the palace. The walls were freshly whitewashed and hung with tapestries, many of which had been bought specially in Venice by Duke Ercole’s agent (Fiorini had not been trusted with this task). Mosto and Fiorini counted seventy-two individual pieces of tapestry of varying shapes and sizes. Fiorini recorded their precise measurements in the inventory but not the stories they represented, referring to them generically as scenes of hunting, animals, figures, woods or landscapes. Ippolito’s kennel master, whose talents also extended to needle and thread, had spent much of the summer (fifty-five days in total) lining the tapestries with blue cloth and sewing on pieces of leather to hold the rings used to hang them.

Ippolito’s apartments were at the back of the palace, away from the noisy clatter of the street. The rooms looked out over the garden and faced north, cool in summer and furnished with elegant fire-places for winter. The suite consisted of five rooms and there were no corridors. Each room opened directly into the next and, though they were smaller than the reception halls, they were just as lavishly decorated. Like the halls, they were hung with tapestries.

It is difficult to be certain of the exact size of the rooms in Ippolito’s apartments since this part of the building has been considerably altered since he lived there, but the quantity of new glass windows he installed gives us a rough guide. The first room, and the most public, was his private drawing-room, which had four windows overlooking the garden. The next room was the antechamber, which had only two windows. It was also the only room without an elaborate painted ceiling and contained instead nine painted panels (sadly Fiorini did not record their subjects), four of which had been done by Jacomo Panizato before he took up employment in the stables. The third room, Ippolito’s bedroom, had three windows, and off it lay the camerino, a small room with only one window (and a windowless bathroom beyond). Finally there was his study, or studiolo, a room with two windows where Ippolito stored and displayed his collection of valuables.

Rooms of the period were sparsely furnished by our standards. Ippolito’s inventory lists just two armchairs, one of which was covered in white leather. Most of the seating furniture was light and portable. There were plain wooden benches, which were covered with tapestry cushions decorated with greenery and animals. Many of the rooms had tables, some covered with valuable Eastern carpets and rugs, and all the fireplaces were furnished with fire irons and wooden bellows, though only one fire screen was listed in the inventory. The principal ornaments in each of the rooms were large carved wooden chests which were used for storing clothes, linen and other goods. Ippolito owned twenty-nine in all, most of them made of walnut and many equipped with heavy locks. Fiorini had bought several of these in Venice, and others had been ordered from cabinet-makers in Milan ‘in the French style’. One particularly grand walnut chest, which had drawers for displaying his collection of medals, had been a present from his father. A small cypress wood box in which he kept his handkerchiefs and nightcaps had been a present from his sister Eleonora, Abbess of the convent of Corpus Domini. There were also two painted cupboards, one of which was in the camerino and contained his library, a rather grand description for the ninety-nine books he owned.

In striking contrast to his scanty collection of furniture, Ippolito had amassed a princely collection of precious objets. He owned carved crystal reliefs, carved crystal cups, two astrological globes, pieces of coral, an ivory sundial, two mirrors of polished steel, fifteen antique bronze statues including one of a satyr which had been made into a lamp, and over 300 medals and coins. One of the medals, in gold and enamel, had been made in 1531 by the goldsmith Giovanni da Castel Bolognese and was inscribed with a bear. The bear was the symbol of the early Christian martyr St Euphemia and of Callisto, the nymph seduced by Jupiter and turned into a bear by Diana for abandoning her vow of chastity. It was also widely used as a symbol of gluttony.

Even the objects Ippolito used every day were expensively made. His inkwell was of gilded alabaster, the sandbox he used to dry the ink on his letters was made of silver, his chamber pots were crystal and his air-fresheners were perforated balls of copper and silver filled with musk. The pestle and mortar used to grind the perfumes that filled the balls and that scented his gloves were made of alabaster. Rather surprisingly, for a man whose father had been a patron of Titian and who himself would become one of the greatest patrons of art twenty years later in Rome, Ippolito’s collection of paintings, at this point, was not particularly impressive. He owned just ten. Eight were religious: a St John the Baptist, a St John the Evangelist, five scenes from the life of Christ, including a Circumcision and a Massacre of the Innocents, and a devotional image of the Virgin, a common feature in bourgeois and noble homes across Europe. Ippolito’s Virgin was, inevitably, particularly lavishly set in a carved wood frame decorated with expensive ultramarine which, as Fiorini recorded in October, was in the process of being being touched up by Jacomo Panizato. The other two paintings were secular: large oil portraits of women by the Venetian artist Palma Vecchio. One would like to think that Ippolito followed contemporary fashion and hung these two paintings of women on the walls of his bedroom. (His cousin Guidobaldo della Rovere commissioned Titian’s Venus of Urbino for his own bedroom. This was not a Venus, as modern art historians coyly describe her, but a sensuous and seductive female nude, a sixteenth-century version of the Pirelli calendar.)

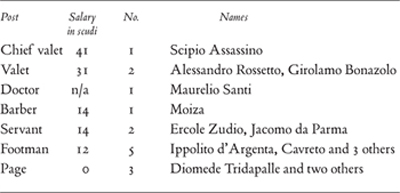

The Chamber staff

Ippolito’s bedroom was the grandest room in his apartments. He slept in an enomous four-poster bed, supported on gilded classical columns complete with bases and pedestals. His fine linen sheets were embroidered with silk and the bed-hangings were made of red and white silk. The painted ceiling of the room, with its 110 gilded rosettes, had taken Andrea and his team 320 man-days to complete.

The staff in charge of Ippolito’s apartments were the officials of his Chamber. Head of this department was Scipio Assassino, Ippolito’s valet for the last eight years, who was now in charge of fourteen men and boys. The men of the Chamber were Ippolito’s public face. The valets, footmen and pages were an essential part of his escort on official occasions. Dressed in outfits made by the Wardrobe, in various combinations of his personal colours (orange, white and red), they accompanied him to mass in Ferrara cathedral on major feast days, to the gates of the city to greet important visitors or to dine in state at the ducal castle. The footmen were in control of access to Ippolito’s private rooms, escorting visitors to their master’s presence (and making expedient excuses to those he did not wish to see). It was Ippolito d’Argenta’s job to hand out alms, while more personal presents were delivered by the valet, Alessandro Rossetto. These men were also in charge of Ippolito’s private and personal life. Ippolito had to trust them with his most intimate habits, in the bedroom and in the bathroom – though any interesting secret or scandal would doubtless have been a topic of gossip throughout the palace. It is not surprising to find that Assassino, Moiza and Zudio had all been with him since he was 16. Their names are interesting. Despite its connotations Assassino was an aristocratic surname, but Moiza and Zudio were both nicknames. Moiza was local dialect for Moses – perhaps the barber was elderly – and Zudio translated as Jew, though it is not clear whether this was a reference to his race, his personality or his facial features.

Assassino and the valets dressed and undressed Ippolito, woke him up in the morning and put him to bed at night, and ran his errands about town. Moiza the barber trimmed Ippolito’s beard and perfumed it with citrus and jasmine oils. Zudio took charge of Ippolito’s linen and washed his underwear and nightcaps. Most of the menial work was done by the footmen who cleaned the floors, tidied tables, lit the fires, filled the copper warming-pans with hot charcoal, replaced the burnt-out candles in the silver candlesticks, heated his bath water in a huge copper, changed his bedding and emptied his bedpans. Two of the three pages attached to the household were Ferrarese, but the third was a Mantuan noble, Diomede Tridapalle, who remained with Ippolito for the rest of his life, ending up as Master of the Wardrobe. It was the job of one of the servants, Jacomo da Parma, to look after the pages. He did their washing, bought soap, shoelaces and other necessary supplies, and ensured their heads were washed every fortnight to keep the nits at bay.

![]()

Ippolito led an incredibly busy life in Ferrara, though not, at this stage, a particularly productive one. He was exactly the kind of rich secular cleric who goaded reformers to condemn decadence and idleness in the Church. Ippolito had not been to Milan since his appointment as the city’s archbishop, though there were political reasons for this. Nor is there any evidence to suggest that his religious duties went beyond the conventional behaviour expected of a layman of his background. The fact that he had three chaplains tells us more about his position in society than his piety. Indeed reading the account books and letters, it is often difficult to remember that he was an archbishop. Once his official duties were done, and they were minimal, he devoted himself wholeheartedly to the pursuit of pleasure.

In February 1535 he went off to Bologna for the Carnival celebrations as the guest of a friend, Ridolfo Campeggio. Ridolfo was the son of Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio, a devout lawyer and a reformist who had taken religious vows after the death of his wife and who owed his red hat mainly to his legal talents. One has to wonder what he made of Ippolito. Ippolito was initially rather scornful about the quality of entertainment on offer in Bologna, complaining to Ercole that there were no grand jousting tournaments or masked balls. He had a decided view of his own standing in society and Bologna was not an aristocratic court (it was ruled by a papal governor). But his mood improved as the celebrations reached their crescendo. There were parties every night and, though they may have lacked the courtly flair to which he was accustomed, they did not lack female charm. The last night of Carnival culminated in an all-night party hosted by Ridolfo, where, as he happily anticipated in a letter to his brother earlier in the day, ‘there will be a great quantity of the ladies of the city’.

![]()

By May Ippolito felt jaded and went to Reggio, an area still famous for its mineral springs, to take the waters. Even there, pleasure came first. It took him a week to start the cure. First he complained it was raining too heavily and then that he was unable to refuse an invitation from Ercole’s governor in Reggio to attend his wedding. He finally started the health regime two days later but had to stop almost immediately because of the moon (it is not clear from his letter which particular phase of that heavenly body was interfering with the cure). Two weeks later he was well enough to go hunting and set off with his courtiers up into the Apennines outside Reggio to stay with another friend, Count Giulio Boiardo, whose estate at Scandiano was part of the Este duchy. The first evening they went out with their sparrowhawks and caught several pheasant. The next day, while they were messing around after lunch, Tomaso del Vecchio, one of Ippolito’s gentlemen, managed to fall off his horse and break his leg so badly that the shin bone protruded through the flesh.

Ippolito indulged in all the sports, physical and sedentary, available to a young aristocrat in sixteenth-century Europe. Amongst the furniture in his apartments was a chess set, a zarabotana board (a game of chance, played with dice) and a bag for his gambling money, which, as Fiorini noted in the inventory in October 1535, contained 75 scudi. Like the rest of his family he was a keen musician. He owned two clavichords and there were eighteen song books in his library. His household included a musician, Francesco dalla Viola, who was the brother of Alfonso, the master of Ercole’s music. The importance the Este attached to music was reflected in Francesco’s handsome salary of 46 scudi a year, more than Ippolito’s valets or even the Master of the Stables. Ippolito was also a keen card-player and a successful gambler, but his preference seems to have been for more physical sports. He played a lot of real tennis, wagering bets on the outcome of the matches. Above all, he hunted and jousted. The list of his weapons and armour covers more than three pages of the inventory. He owned over fifty assorted spears, lances, swords, axes and daggers. Many of the swords had Spanish blades imported from Toledo and were topped with elaborate silver hilts made in Ferrara. There were also more exotic weapons such as a catapult, a crossbow and a scimitar, but no gun (a weapon of war not sport). Then there were caparisons for his horses, as well as iron neck-pieces, shin-pads, spurs, elaborately gilded and decorated shields and several complete sets of armour, one of which was specified as battle armour, complete with steel gauntlets.

Hunting and hawking were perhaps Ippolito’s greatest passions. Many of the weapons listed in the inventory were spears for hunting boar and deer. This sport required special clothes and equipment. Ippolito owned leather jerkins and coats split up the back for riding, six hunting horns, one of which was described as English, several game bags, silver and gilded brass collars for his dogs, and sets of jesses, leashes, bewits, bells and hoods which he bought in Milan for his falcons. Both the dogs and the falcons were kept at Belfiore, where he employed two kennelmen and five falconers, all of whom were given thick black fustian jackets, rough white shirts, stockings and leather boots as part of their salaries. Ippolito owned boarhounds, pointers and greyhounds, dogs that were highly prized. Since most of them were acquired as presents, it is difficult to guess how much they cost, but they were comparatively cheap to feed: they ate sheep’s heads on occasion but mainly slops thickened with the sweepings of husks collected in the granaries.

Hawking was a more expensive hobby. Ippolito owned sparrow-hawks, goshawks, lannarets, sakers and especially peregrines. They were expensive both to buy and to keep. Sparrowhawks cost 1 to 2 scudi each, but a peregrine falcon could cost as much as 10 scudi, the price of two ordinary horses. Fiorini’s ledgers contain payments for herons and bitterns, used to train the birds, and medicines to treat their numerous ailments, especially powdered orpiment (arsenic trisulphide) to get rid of lice. They were fed on raw meat, at 25 soldi (0.36 scudi) each a month, exactly the same rate as Ippolito paid members of his household for their food expenses – the men were not undernourished, it was the hawks who were expensively fed.

![]()

The principal pleasures of the rich in sixteenth-century Europe were taken at the table. Dining and its associated entertainments were an essential part of the culture of the Renaissance. Nearly half of Ippolito’s staff were directly concerned with food and drink, and were known, in the quaint terminology of Ferrara, as the Officials of the Mouth (Offitii della Bocca).

The Officials of the Mouth

The basic running of the Palazzo San Francesco was in the hands of Alfonso Cestarello, the major-domo, who did not receive a salary but who was rewarded with benefices. It was his job to ensure that the palace was adequately stocked with essentials such as wine, firewood, candles and brooms as well as non-perishable foodstuffs. The fire-wood was kept in a storehouse which Cestarello had rented in April 1535 (for 6 scudi a year) in the narrow alley between the palace and the church of San Francesco, and it had been stocked during the summer with large quantities of wood from Ippolito’s estates. It was Cestarello’s job to draw up contracts with butchers, poulterers and fishmongers for regular supplies of meat and fish. He was also responsible for the stocks of live poultry, which were fattened in coops near the kitchen. He had a new chicken coop built, which must have been quite a substantial construction because during October and early November it was stocked with 149 birds (63 capons and 86 pullets). Most of the pullets came from Cestarello’s own estates, and he charged Ippolito the market price for them.

Cestarello also supervised the stocking of the wine cellar, which was furnished with new tubs for pressing grapes, barrels for wine and vinegar, handcarts for moving the heavy containers, trestles for stacking the barrels, locks for the cellar door and, of course, wine. Ippolito himself drank fine wine, much of which was imported. He was particularly fond of malvasia (malmsey), a strong sweet wine which he bought in Venice. Cheaper wine for the household came from Ippolito’s estates, and once again Cestarello took the opportunity to sell Ippolito several barrels of his own. Wine had a variety of uses. Not only was it the basic drink at all levels of the household (there was no tea or coffee, and the water was dangerously full of germs), but it was also used in the stables to wash down the horses and mules.

Easily the most expensive item on Cestarello’s shopping list for the palace was oil. He commissioned two huge new stone vats (at 2 scudi each) for the larder – six porters were needed to carry them from the stone-cutter’s workshop to the palace. These vats were filled with high-quality oil from the Marche and Puglia, bought by Cestarello from local apothecaries: a total of 4,800 kilos, surprisingly measured by weight, at a cost of 182 scudi.

The larder (dispensa) and its stock of non-perishable goods were under the care of Carlo del Pavone, the new larderer (dispensiero). These goods were regularly inventoried to avoid theft. Carlo counted or weighed goods as they came in and went out, using a set of scales which was checked annually, and then entered the details in his ledger. Cestarello inspected the ledger weekly. The larder must have been a haven for the hoarder, and it was filled with pungent odours. Most of the spices were bought in Venice, where saffron, ginger, nutmeg, mace, pepper, cinnamon and cloves were all easily available, at a price. The loaves of Madeira sugar and white beeswax candles also came from Venice, but the rancid tallow candles and torches, made from rendered animal fat, were supplied by local tradesmen, as were the blocks of lard, jars of almonds, raisins and other dried fruit, and pasta. The bulk of the stores came from Ippolito’s estates: honey, lentils, beans and other pulses from his farms, and cheese sent as part of his dues from Milan. The hams and salamis that hung from hooks in the ceiling were all made from his own pigs. It was normally Cestarello’s job to supervise the making of these but he must have been busy elsewhere in January 1535, because Tomaso Mosto was put in charge of this annual event. Mosto organized the killing of over fifty pigs and bought the other necessary materials: salt to treat the meat, intestines to case the salamis, string to bind them and pepper and powdered cloves to spice them. The meat and the materials were all transported to the house of Laura Dianti, Ippolito’s stepmother, who supervised the work: she sent 82 hams to the larder in February and 209 salamis in April.

The man responsible for dining in the palace was Girolamo Guarniero, the chief steward. He was in charge of the preparation and presentation of all Ippolito’s meals. He had to organize the menus for lunch and dinner each day, and the banquets if there were guests. He planned the cooked dishes with Andrea and Turco in the kitchen, the salads with the credenzieri, Gasparino and Zebelino, and the wines with Priete (these last two were nicknames: did Zebelino resemble a little marten or Priete a priest?). Guarniero then ordered the necessary staples from the palace stores, Cestarello’s department, and gave a shopping list of fresh ingredients to Zoane da Cremona, the spenditore, or purveyor. (Zoane was Ferrarese dialect for Giovanni.)

Neither Guarniero nor Cestarello did any shopping themselves, but Zoane went out most days, including Sundays and holidays, to buy the stores needed by Cestarello. In addition he purchased all the perishable goods for Guarniero to give to the cooks and credenzieri for that day’s meals, inspecting the greengrocers’ shops for salad, fruit and vegetables, and combing the market stalls for seasonal produce, such as pheasant, partridge and the other little game birds of which Ippolito was particularly fond. He also bought extra items of meat and fish, especially delicacies such as oysters and eels which were not supplied on contract. His job was a responsible one. Like Panizato at the stables, he was regularly given large sums of cash – 50 to 100 scudi, two or three times a week – and he had to account for every penny, recording each item he bought in his ledger, which was regularly checked by Guarniero.

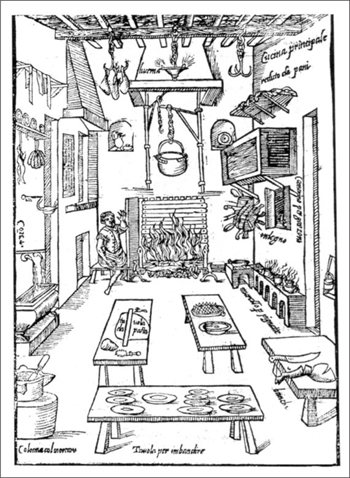

Guarniero had been busy throughout 1535 stocking the various sections of his department, in particular the kitchen. The room had been completely refurbished by the builders, who had rebuilt the well, retiled the floor and installed two new windows, their panes covered with cloth. Ippolito’s chief cook was Andrea. Like Andrea the painter, he was simply described as Andrea the cook (Andrea cuogo) in the ledgers. He had trained in the ducal kitchens, working as an under-cook for Duke Alfonso, and he received a modest golden hello of 4½ scudi in February 1535 from Ippolito. He seems to have lived at home with his wife Catelina and their children because the family received allowances of firewood, candles and wheat in addition to his salary of 24 scudi – it is a mark of the importance Ippolito attached to his food that he paid his chief cook nearly the same salary as the much more public post of carver. The same month Guarniero sanctioned Andrea’s order for forty-two items of kitchen equipment from a merchant who sold copperware on the Via Grande in Ferrara. The goods, which came to 21 scudi, were mostly copper and iron saucepans, but they also included three steel frying-pans. Either the price or the quality, or both, must have shocked Guarniero, because a week later Fiorini was sent to Venice to buy the rest of the equipment needed. He returned with glasses and wine jugs for Priete, two large candlesticks for the credenza and another ninety-eight items for the kitchen (which only cost 30 scudi) – more saucepans, large copper cauldrons for boiling water, copper mixing bowls and others for skimming cream from the top of the milk, copper baking tins, iron ladles for soups, iron graters to grate sugar from the loaf and glazed terracotta pots for stewing, as well as iron pot chains, trivets and meat spits. One of the chaplains, who had business in Verona, returned with fire bricks for the palace fireplaces and two pestles and mortars, made of the red marble for which Verona was famous (the same red marble that decorates the façade of the Doge’s Palace in Venice). A surprising gap in the shopping list was kitchen knives: one of Andrea’s jobs, for which Ippolito reimbursed him, was sharpening these knives, but it is likely that the cook provided them himself as the tools of his trade.

Kitchen interior

Sixteenth-century cooking pots

Sixteenth-century kitchen knives

Ippolito and his household ate three times a day. Breakfast was little more than a snack. The footmen just had bread and wine, though Ippolito himself ate something slightly more substantial when he got up in the morning. The two main meals of the day were lunch, eaten at midday, and dinner, eaten in the late afternoon or early evening. The basic diet of the entire household was good, and those from the lower levels of society almost certainly ate better than they would have done at home. There were large quantities of meat and fish, as well as fruit and vegetables. The daily food allowance Ippolito paid to the top members of his household was based on 460 grammes of meat or fish a day. The courtiers had veal, while their servants and less important members of the household ate only cheap beef, but they all had fish on fast days. The number of lean days varied from eight to twelve days a month, and of course the whole of Lent was lean. Above all there was bread. One academic has estimated that an average of 1 kilo of bread per person per day was eaten in the palaces of the rich. Ippolito supplied some of his household with monthly allowances of wheat, enough to make an 800-gramme loaf of bread every day – the same weight as a modern sliced loaf. These quantities of bread must have helped to mop up the 2 litres of wine they each drank every day.

With the exception of Ippolito, who dined at his own table, and the stable boys, who made their own eating arrangements, the household all ate together in the staff dining-room (tinello). This was a big room near the kitchen with three large cloth windows and a fireplace. At the ducal palace the gentlemen and senior valets ate in their own dining-room, but there is no mention at this stage of a separate room for them in Ippolito’s ledgers. However, the tinello was divided into two by a brick screen, and it seems likely that the grander staff did have an element of privacy from the rest of the household. The furnishings were serviceable. On his trip to Venice Fiorini had bought eighteen brass candlesticks for the room, cheap plain glasses and pewter plates, bowls and wine jugs. Another feature of the room, specially commissioned by Fiorini, was a purpose-built urinal set, which consisted of an iron stand holding a copper basin for hand-washing and a copper pail below. It was the job of Arcangelo, the table-decker, to lay the tables in the staff dining-room, using plain white tablecloths and napkins which he got from the wardrobe, all of which were duly detailed in the wardrobe ledgers. He was also responsible for clearing the tables, tidying the room afterwards and, presumably, for emptying the basin and urinal.

Ippolito’s table was, inevitably, far more grandly furnished. He dined with his guests, male and or female, using crystal glasses, which cost as much as four times those in the staff dining-room (Fiorini had bought these glasses in Murano, and many were gilded). His candlesticks were silver, and so were his plates. His tablecloths and napkins, also supplied by the wardrobe, were made of fine linen. His pages brought round bowls of scented water for him and his guests to wash their hands – no urinal set for them – his meals were served by Vicino and the other squires, and his meat was carved by Alfonso, his professional carver. Guarniero worked hard to create an atmosphere of gracious living. It was his responsibility to ensure that the tables were laid to perfection, that Priete was serving the correct wines and that he had washed the glasses properly. Guarniero also had to ensure that the credenza looked suitably impressive. In addition to preparing the salads and other cold dishes, Zebelino and Gasparino had to decorate the credenza, using the silver left to Ippolito by his father and freshly laundered tablecloths and napkins, which they collected from Mosto, and signed for in the wardrobe ledgers.

It is difficult to tell exactly what Ippolito and his guests ate in the Palazzo San Francesco during the winter of 1535/6 because Zoane da Cremona’s ledgers are missing. However, Messisbugo’s treatise on banquets includes a lot of recipes which give some idea of Ippolito’s diet. Lunch and dinner usually consisted of four courses: a first course of fashionable salads, followed by two courses of meat or fish (depending on whether the day was fat or lean) and a dessert of sweet dishes, jellies, fruit and cheese. Meat and fish could be boiled, roasted, fried or grilled, and either served plain or with an accompaniment. Messisbugo gives recipes for grilled bream with parsley and chives, fried sardines with oranges and sugar, and roast veal with morello cherry sauce. Many of the recipes are surprisingly familiar – though more highly spiced and richer than we might choose – such as one for an apple and onion sauce, flavoured with ginger and nutmeg, another for fresh egg pasta stuffed with meat or, more exotically, with pine nuts, raisins and spices, and a dessert recipe for a ricotta cheese tart filled with pears, apples, quinces or medlars. In keeping with the fashionable interest in peasant fare, some recipes were austerely plain. A ‘thin English soup’ was made with scraped parsley roots and ginger, thickened with egg yolks beaten with a little vinegar, and poured over toast. Another soup was actually called a peasant dish (though it is difficult to imagine a peasant being able to afford it). It was made of chopped roasted hazelnuts boiled in meat stock with a piece of beef fat, flavoured with sugar, cinnamon, pepper, cloves and saffron, and served cold (a Lenten version was boiled in stock made from pike).

The international ambitions of the Ferrarese court were evident in recipes for French and English sauces. The French sauce (which Messisbugo particularly recommended for boiled or roast capon) was made simply by adding orange juice to the pan juices and flavouring the sauce with sugar and cinnamon. The sauce he called English, which he thought would suit boiled sturgeon or veal, was the same as the French version, but with the addition of pepper, a few cloves and a little mashed ginger root, with fresh fennel seeds sprinkled over the finished dish. He also described an Italian sauce which was made by mashing a cooked calf’s kidney with two or three egg yolks, flavoured with spices and salt. The presentation of food and the importance of appealing to the eyes as well as the stomach were constant themes. Messisbugo’s recipe for boiled eels – a much-prized speciality of Ferrara – served with a spiced sauce included the advice that it should be poured over the eels in a window-pane pattern.

Ippolito’s first major banquet at the Palazzo San Francesco was held on Saturday, 5 February 1536, in honour of his aunt, the 61-year-old Isabella d’Este, who was on a visit to Ferrara. The guests included Ercole and Renée, and his other brother, Francesco. During the afternoon there was jousting in the street in front of the palace, which was covered with twelve carts of sand (at a cost of 10 scudi). Inside the palace the Great Hall was lavishly decorated for the feast. Three carpenters spent a whole day hanging the chandeliers – Ippolito borrowed fourteen from one of Ercole’s courtiers, as well as 350 wicks (bundles of greased rags) to light them. They also erected a wooden frame which was hung with greenery. Two painters spent four days painting and gilding the paper decorations which hung from the chandeliers together with the coats-of-arms of all the principal guests – Ercole, Renée, Francesco and Isabella. Even the candles were painted in dark red and orange, Ippolito’s own colours. Without the details of Zoane da Cremona’s account book, it is difficult to work out exactly what food the purveyor bought for the banquet but it was certainly expensive. His advances, recorded by Fiorini, doubled from an average of 37 scudi a week to 69 scudi during the week of the banquet. Fiorini also entered a payment of 5 scudi for sugared almonds and another of 34 scudi to cover the cost of pheasant, partridge and truffles supplied for the party.

![]()

Ippolito and his household were destined to spend only another month enjoying the luxury of the Palazzo San Francesco. In the summer of 1535 Ippolito had received a formal invitation from Francis I inviting him to join the French court, and the King had given him a lucrative benefice as a sign of his favour. However, there seemed to be no urgent need to fix a date for his departure. Besides, Ercole wanted his brother in Ferrara that autumn while he was absent in Rome and Naples, trying to resolve various political issues with Pope Paul III and Emperor Charles V.

On 1 November the situation changed dramatically when the Duke of Milan died without an heir. Charles V adroitly moved his armies into the duchy and claimed the title. Francis I responded immediately by provocatively invading Savoy. The uneasy peace that had existed in Italy for the last six years was now threatened. Duke Ercole, keeping his options open, decided to send Ippolito to France, and their younger brother Francesco to the imperial court. Despite the season Ippolito must leave immediately.

Shortly before his departure, Ippolito held another, more intimate, dinner party. Once again, we know nothing about the menu, though the shopping list included a whole calf, ten chickens, sixteen pigeons, six ducks, spices, cheese, oranges, lemons, pears, raisins and white bread. However, the guest list was intriguing. The guest of honour was a lady named Violante Lampugnano. She was probably the daughter of Pietro Lampugnano, a Milanese noble who had been Lucretia Borgia’s steward, and she may well have been a friend of Ippolito’s since childhood. She was certainly a regular guest at his banquets and she was probably also his mistress, a rumour widely reported by the diarists of Ferrara. Even more intriguingly, the scandalmongers suggested that Violante bore Ippolito a daughter.

The child certainly existed. She was named Renea after Ippolito’s sister-in-law, brought up in Ferrara and educated in Bologna under the guidance of the wife of Ridolfo Campeggio. In 1553 she was married to Ludovico della Mirandola, with a trousseau of clothes and jewels worth over 3,000 scudi supplied by Ippolito. In 1554 Renea gave birth to a daughter named Ippolita, an unmistakable token of her affection for her father. She died the following year of quinsy. But when was Renea conceived? Assuming Violante was indeed the mother, the options are limited. After his departure for France Ippolito did not return to Ferrara until the summer of 1539 and then only stayed for two months. If Renea was conceived during that brief period, she would have been only 13 when she married, young by the standards of Este princesses who did not usually marry until they were 16 or 17. It seems more likely that Renea was conceived some time in 1535 or early 1536 and that when Ippolito set off for France a week or so after the dinner, he left behind either a baby daughter or a pregnant mistress.