3

On the Road

IPPOLITO LEFT FERRARA for France on the morning of Monday, 13 March 1536, saying a formal farewell to his brother in the main square in front of the ducal palace. Ahead of him lay the long journey to Lyon, from where Francis I was masterminding the invasion of Savoy. Neither Ippolito nor his entourage of 116 men knew how long it would be before they would return. As their horses clattered down the narrow streets, through the city gates and out into the countryside, one wonders how they viewed the journey ahead. The younger members of the party might have looked forward to a month in the saddle but the older men must have viewed the prospect of stiff and aching joints with understandable apprehension. The stable boys and muleteers were about to make the entire journey on foot. Few of the men had been beyond the borders of the duchy. Even Ippolito had never travelled out of northern Italy, and none of them had ever crossed the Alps. They would also have to pass through the duchy of Milan, currently in imperial hands. They were unsure of what sort of reception they would receive, particularly in light of the recent news that Francis I’s armies had invaded Savoy and were poised to take Turin, an action deliberately designed to provoke Charles V into war.

Ippolito was taking most of his household proper with him to France: fifty-two out of a total of seventy-two. All the gentlemen were leaving, as well as his secretary Antonio Romei, his musician Francesco della Viola, and his Master of the Wardrobe Tomaso Mosto, together with his two assistants. Scipio Assassino and all the Chamber staff were in the party, including the three young pages. One of the footmen, Cavreto, was leaving his wife behind with their baby daughter, who had been born a few days earlier – Ippolito gave her a present of 3 scudi. Most of the stables’ staff were travelling: Pierantonio, the chief trainer, Jacomo Panizato, who looked after the stables’ expenses, the saddler, the farrier and twenty-three stable boys and muleteers (two assistants were left behind to look after Ippolito’s carthorses and brood mares). There were also three of the falconers with their cages of falcons, though Ippolito decided to leave his dogs behind, perhaps unsure of how they would look in France, though they joined him later that year. Girolamo Guarniero was taking all the dining staff: Alfonso the carver, Priete the sommelier, Andrea and the other cooks, the two credenzieri, Zebelino and Gasparino, and their assistants. Alfonso Cestarello was coming too, but his staff were staying behind to look after the stores at the Palazzo San Francesco, under the watchful eye of Jacomo Filippo Fiorini, Ippolito’s factor. Zoane da Cremona was also travelling, with his ledger carefully stowed away in his pocket. It is this ledger, a thin notebook the size of a green Michelin guide, which reveals so much about the process of travelling in sixteenth-century Europe.

Nearly half the men waiting outside the ducal castle were not members of Ippolito’s household but their servants. His gentlemen were travelling with three servants each, Romei and Assassino had two, and Guarniero had four, while the two chaplains shared one. The other ten belonged to Zoane da Cremona, Francesco dalla Viola, Pierantonio, the two valets, the doctor, the three squires and the carver. It was a sign of Ippolito’s rank in society that even his valets and squires were grand enough to have their own servants.

Most of the men were young and single, and some of the older ones had opted for Church careers rather than marriage. There were no women in the party, though there must have been plenty of broken hearts left behind in Ferrara that day. Ippolito made no special arrangements with Fiorini for the care of girlfriends or mistresses of his staff while he was away (nor for Violante), but he did do so for the few of his men who had wives. Catelina, the wife of Andrea the cook, was to receive half her husband’s salary every month (12 scudi a year), as well as an allowance for food, enough to buy 460 grammes of meat a day (worth over 4 scudi a year), and regular handouts of candles, wheat and firewood. The arrangements made for Pierantonio’s wife, also called Catelina, were more generous. In addition to half of her husband’s salary (17 scudi), she was also to get a monthly allowance of wheat, and Ippolito paid the rent on a house for the family (5 scudi). Onesta, the wife of Besian the falconer, received none of her husband’s income, but Ippolito rented a house for her (7 scudi a year) and arranged for Fiorini to give her regular supplies of wheat. He also bought a house costing 20 scudi for the family of Zudio, his faithful personal servant. Much the saddest tale is that of Bagnolo, the head stable boy, who had been with Ippolito since 1531. He seems to have lost his wife in childbirth, and their baby son, judiciously named Ippolito, was left in Ferrara with Bagnolo’s brother-in-law. Fiorini paid him 3 scudi a year, a sum not deducted from Bagnolo’s wages, to cover the extra costs of caring for the child, as well as supplying him with flour and wheat.

![]()

The start of the journey must have been a welcome relief for the household. Ippolito had no concept of travelling light (though it should be said in his defence that he was effectively emigrating, not just going on holiday), and they had spent two exhausting months preparing for the trip. Twenty-three pack mules and three horses laden with luggage followed the horsemen out through the city gates.

The first piece of evidence in Fiorini’s ledgers to indicate that the date of Ippolito’s departure had been set came on 21 January when Pierantonio started to buy mules. A week later he sent Vicino to Pesaro, who returned with two more (costing 109 scudi) and a muleteer. Other mules and muleteers were generously lent by Ercole II from the ducal stables, and Pierantonio had to negotiate the choice of these with his counterpart at the castle. He also had to find mounts for all the household. In late February he spent 188 scudi on thirty-seven horses. At an average price of 5 scudi per horse, these were not thoroughbreds but ordinary hacks, and Ercole the saddler spent much of January and February making saddles and harnesses for them.

There was also the luggage itself. There was no question of simply buying a number of identical tea chests or ready-made suitcases: everything had to be custom-made. The basic boxes were constructed in wood by local carpenters and delivered to the stables, where Ercole the saddler covered them in leather. Fiorini bought eight cowskins, dyed red, black or green, for this purpose, as well as 4 kilos of fat to grease them. Many of the boxes had to be reinforced with iron bands and secured with heavy locks. Ippolito already had his own gilded vanity cases, which Zudio filled with soap, powder and perfumes, but most of the luggage was new. There were small cases for Moiza the barber to pack his oils and shaving equipment, boxes for Jacomo to pack clothes for the pages, two large crates for Zebelino to fill with the credenza silver and another pair in which Priete packed Ippolito’s gilded crystal glasses. Andrea the cook was allocated one mule for all the kitchen equipment. Most of the crates were made to transport the linen, furnishings and clothes in Ippolito’s wardrobe. Ercole covered special flat cases to hold the tapestries, and quantities of crates for all the furnishings, table linen, bed linen and jewels Ippolito wanted to take to France. Mosto ordered black velvet bags for Ippolito’s prayer books and four more small boxes to hold Ippolito’s communion set (the cross, two candlesticks and the calyx). These were too delicate for Ercole the saddler to cover, so they were given to a scabbard-maker in Ferrara who also lined them. Finally, Mosto commissioned a large strong box, heavily reinforced with iron bands and secured with padlocks, to carry all the money and valuables. Ippolito took a credit note for 2,000 scudi from Renée, which he could cash with his sister-in-law’s bankers in Lyon, and over 3,000 scudi in cash for the journey.

The prospect of life at the French royal court provoked a veritable orgy of shopping. Ippolito bought twelve jewelled rosaries as presents for the ladies at court, a suit of armour and an expensive sword with a gilded black hilt. He spent 21 scudi on two Flemish tapestries and bought several new chairs, rather grandly upholstered in black velvet ornamented with gold studs. He also ordered a lot of silver to enhance the glamour of his dinner parties: three gilded salt cellars and three silver candelabra with ten branches each, for the table, and twelve spoons and twenty-four plates to add to his father’s silver on the credenza. Mosto commissioned these items on Ippolito’s behalf from two silversmiths in Ferrara, giving them 4,636 silver coins, worth 441 scudi, to melt down to make the items, together with 3 gold coins to use for gilding the salts. The contracts he drew up with the silver-smiths were very precise, specifying the exact amount of silver to be used for each item, and the fee that the silversmiths would be paid for manufacturing the goods. The spoons were the most expensive item per weight, suggesting that they were highly decorated.

There were also more practical purchases. Mosto ordered three fine linen shirts for Ippolito, two of which were embroidered by Sister Serafina at San Gabriele. He paid hatters for several new hats, four of which were made in black English cloth, and bought 170 kilos of good-quality white soap from Venice (7 scudi). Dielai, Ippolito’s shoemaker, put in a bill for 6 scudi for boots and shoes, including two new pairs of tennis shoes, which he would certainly need in France. Ippolito’s superb four-poster bed was too large to transport, so he bought a smaller one, made of walnut, with two new mattresses and a lot of bed linen, while Mosto found a rather ornate set of hangings, costing 5 scudi, for the new bed, made of dark red satin with cords and fringes of gold and silver thread. Ippolito also took a large quantity of materials to France. Mosto ordered black velvet from Venice and silks from Florence, and also bought a large quantity of red silk thread in Ferrara. They must have been busy in the wardrobe that day as this was collected from the haberdasher’s not by Mosto’s assistant but by one of the stable boys. Finally, the day before they left, Mosto paid all the bills he had run up with Ippolito’s regular suppliers since the beginning of the year, a total of 226 scudi.

Ippolito’s journey from Ferrara to Lyon in March 1336

![]()

The journey to France was not particularly long by the standards of the time. Ferrara to Lyon was 720 kilometres, whereas Rome to Paris was twice the distance. By our standards, however, it was a journey of epic proportions. Now one can do the journey in under an hour by aeroplane, or in six hours by car. Ippolito and his men did the whole trip on horseback, while the stable boys walked the distance, and it took them a month. It was possible to travel more quickly in sixteenth-century Europe. Those on important missions did the journey in as little as six days, averaging 110 to 120 kilometres a day, though travelling at this speed required frequent changes of horses, and a lot of money to pay for them. Really important letters were sent along a chain of couriers and could take as little as two or three days. Ippolito’s business was less urgent, and he was travelling with mules, which only walked at 5 or 6 kilometres an hour.

In fact the first week was astonishingly relaxed. One gets the feeling that Ippolito, understandably, was suddenly reluctant to leave familiar surroundings and embark on a journey that would mark the start of a new phase in his life. The party took two days to cover the 75 kilometres to Modena and spent Tuesday night with Ercole’s governor in the city. That evening Ippolito wrote to his brother complaining that he had had a splitting headache – the ‘hammer’, as he called it – ever since leaving Ferrara. However, it did not stop him accepting an invitation from Giulio Boiardo to go hunting. While the rest of the household travelled the short distance to Reggio, Ippolito and his courtiers rode off into the hills for two nights at Scandiano – luckily there were no mishaps like the year before when Tomaso del Vecchio had broken his leg.

Ippolito left Scandiano on the morning of Friday, 17 March, riding the 11 kilometres down to Reggio, where he joined the Via Emilia. Some time that morning he crossed the border of the Este duchy into the more lawless world of the Papal States, and the journey started in earnest. The party rode 64 kilometres that day up the Via Emilia, avoiding Parma, where riots had made the city unsafe, to Fiorenzuola, where they joined the rest of the household. The following day they left the Via Emilia at Piacenza and headed west towards Turin, 280 kilometres away. There they planned to rest for a couple of days before tackling what would be the hardest part of the journey, crossing the Alps.

The daily routine on the road is easy to reconstruct from Zoane da Cremona’s ledger. The party normally covered 30 to 40 kilometres a day, riding in three different groups. Pierantonio left soon after dawn with the stable boys and muleteers leading the baggage horses, the mules and the spare horses. Walking along the road at 4 to 6 kilometres an hour, with stops for lunch and other necessities, it took them eight hours or so to complete each leg of the journey. The men on horseback could cover the same distance in half the time, providing the road was good. Vicino also left early, with one of the other squires and their two servants, to ride ahead to the next town to announce the party’s arrival. Their principal task was to arrange accommodation for the men, horses and mules for the coming night. Ippolito had a leisurely breakfast (while his staff bought last-minute necessities in the local shops and packed his possessions) and then rode with the rest of the household for two hours or so before stopping for lunch at an inn. For most of the party the ride was the relaxing part of the day. None of them had any work to do, a marked change from life in the Palazzo San Francesco. They could bask in the prestige of travelling in the party of an important man, chat with their friends, marvel at the changing landscape or look at the people they passed on the road: parties of rich merchants, bands of itinerant jugglers, musicians and other entertainers, couriers galloping south with urgent letters for Rome and soldiers travelling north to the war.

Late in the afternoon Ippolito’s party met up with Vicino, Pierantonio and the stable boys in order to make their entry into the town where they were to spend the night. These were not grand occasions like the formal entries staged for the arrival of spouses or important guests, but Ippolito was officially received, with decorum by civic functionaries and with loud ceremony by the town’s trumpeters, pipers and drummers. There were formalities to observe. Ippolito had to tip the gate-keepers, armed guards and musicians, who often received as much as I scudo each (the equivalent of a month’s salary for the footmen, over two months’ pay for a stable boy). Enterprising townspeople seized the opportunity to make a quick scudo. Ippolito would tip itinerant musicians, boys and girls who danced for him, buffoons who amused him, and even those who gave him presents of wine and food. The poor begging on the street also benefited. Generosity was expected of a man in Ippolito’s position, and he gave orders to his footman to dispense coins to the crippled, the poor, the old and the infirm. In Italy Ippolito was particularly fond of destitute French soldiers, though in France he favoured Italians. The tradesmen also stood to profit from the arrival of the party. Zoane da Cremona bought large quantities of food most evenings from the butchers and greengrocers in the town. Farriers would have horses to shoe, saddlers would be given harnesses to mend, and laundresses often had unexpected loads of linen to wash and starch that night. Women must also have been in demand for other reasons – it is difficult to imagine that all 117 men stayed celibate for the entire month, and there are several tips in Zoane’s ledger to unspecified females.

Above all, it was the innkeepers in the town who stood to make the most substantial profits from 117 hungry men and their animals. The party was too large to be accommodated in any single inn and might be lodged in as many as six different establishments, divided up according to rank, with Ippolito and his gentlemen in the best hotel. Negotiating prices with innkeepers in an unfamiliar town must have been a logistical nightmare for Vicino and his fellow squire. The inns had reassuringly familiar names – The Three Kings, The Angel, The Crown – and equally reassuringly familiar ways of extracting cash from their customers. They charged a flat rate for dinner for each man (the price included their beds) and a separate rate for stabling each horse. The rates for the men varied according to the quality of the inn but the price of stabling was usually standard across town, whether for a thoroughbred horse, a hack or a mule. Innkeepers made their profits by charging extra for essential items. The cost of stabling did not include fodder, the cost of dinner included neither wine nor bread, and the cost of the beds did not cover firewood, candles or breakfast. Ippolito also had to pay to have his luggage guarded overnight, another essential service that varied widely in its cost.

The sleeping arrangements were considerably more cramped than at home for all levels of the household. Ippolito had to make do with only a bedroom and a private drawing-room, while his gentlemen had one room each. They had all brought their own mattresses and sheets from Ferrara, and their beds were made up by their own servants. The accommodation may have been uncomfortable by their usual standards but it was much worse for the rest of the household. Many were obliged to share rooms and often beds, probably flea-ridden and certainly dirty. Assassino had to share a room with the other two valets, Zoane da Cremona shared a bed with Gasparino, and other servants slept three to a bed.

The arrival in a town was the start of the evening’s work for most of the household. In particular the stable boys and muleteers had a lot to do. Bagnolo bought cheap wine (usually from the innkeeper) which the stable boys used to wash down the animals to remove the grease and grime which had accumulated after a day on dusty or wet roads. They rubbed fat into sprained muscles and into the places where the leather harness straps had chafed. Bad sores might need one of Pierantonio’s salves, and he would have to buy honey, turpentine and dragon’s blood from the local apothecary. Pierantonio also had to check all the animals each evening, prescribing barley for overtired animals, and give orders to Panizato, who organized their fodder. He went out most days to get broken harnesses repaired or to buy new parts for the pack saddles, which were continually breaking under the weight of Ippolito’s crates. It was a credit to the stables’ staff, and particularly to Pierantonio, that they did not need to replace any of the horses or mules on the journey.

There was also a lot of work to do in the hotel where Ippolito was staying. Assassino and the Chamber staff had to look after their master, unpack their equipment, arrange his rooms and make his bed (and then repack everything the next morning). Zudio often had dirty washing to take to the local laundress. Even on the road Ippolito wore a clean white shirt every day and his sheets were changed regularly. The pages also changed their shirts (though not so frequently) and Jacomo da Parma had to ensure that their heads were regularly deloused.

For some members of staff the work load was markedly lighter than usual. With the wardrobe packed away in its chests, there was not much for Mosto and his assistants to do, which must have made a pleasant contrast to the weeks of hard work before they left. Nor, without a house to run, was there much for Cestarello to do. Ippolito himself had few official duties. He had letters to read and replies to write, or rather to dictate to Romei, his secretary. He was not a great letter-writer and could blame his laziness on the discomfort of travelling.

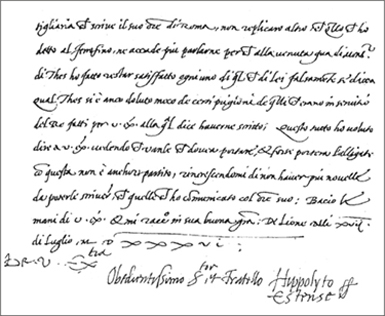

Ippolito’s large and exuberant signature, a marked contrast to Romei’s more businesslike script

Guarniero’s job was also slightly easier than it had been at the Palazzo San Francesco, for he no longer had the household dining-room to consider. As in Ferrara, the stable boys and muleteers ate separately and were given a daily allowance for their food. Most of the rest of the staff ate in the communal dining-rooms of the taverns alongside other travellers. Innkeepers offered at least two set menus, a cheap one for the less well-off and a better one for merchants and other prosperous travellers, as well as an à la carte selection of dishes. The parties that ensued must have been lively because Ippolito was frequently charged for broken crockery and glasses. Ippolito himself ate upstairs in his rooms, together with some of his men. This meal was specially prepared by his own cooks and credenza staff under the supervision of Guarniero. Zoane was sent out to buy the necessary ingredients, while others were supplied (at a premium, of course) by the innkeeper. The dishes were then cooked in the hotel kitchens by Andrea the cook, and most innkeepers charged Ippolito extra for the wood Andrea used.

It is worth looking at the night they spent in Voghera, Sunday, 19 March, in detail. That afternoon Vicino had organized accommodation for 90 men, 23 mules and 96 horses. The stable boys and muleteers would sleep, as usual, with their charges in the stables. There were slightly fewer men in the inns that particular evening, because Alfonso Cestarello (with his three servants and their four horses) spent the night as a guest of Paolo Albertino, one of his close friends. Albertino was Ippolito’s agent for the diocese of Milan and had escorted an unnamed ambassador and his entourage to Voghera, where they joined Ippolito’s party for two days on the road, probably en route for Turin. Ippolito later reimbursed Albertino for the cost of their accommodation in Voghera.

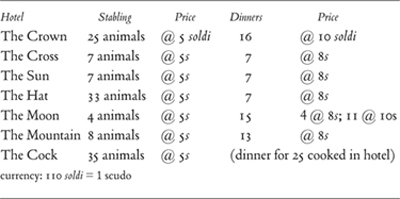

The cost of stabling was uniform, but the price of dinners and beds varied. When Zoane settled the bills the next morning there were charges for morning feeds for all the animals, though only the landlords of The Hat and The Mountain billed him for extra candles and firewood. The innkeeper of The Hat was given a tip, but the landlord of The Cock, where Ippolito was lodged, was not. It is clear from Zoane’s ledger (see overleaf) that Vicino and the two squires were staying at The Cock as well, and, although we do not know the identities of the other men, it is likely that they included Ippolito’s senior courtiers. Guarniero organized dinner for the men at The Cock, which was prepared by Andrea and Zebelino in the hotel kitchens – the innkeeper charged the enormous sum of 60 soldi (just over ½ scudo) for the firewood used in the kitchen and bedrooms that night. The food cost an average of 27 soldi (¼ scudo) a head, substantially more than the set menus eaten by the other staff and servants. Zoane went out shopping soon after the party arrived in Voghera to buy the necessary meat, eggs and salad, while the rest of the ingredients were provided by the innkeeper.

What stands out from Zoane’s shopping list and the innkeeper’s bill are the quantities of bread, wine and meat consumed. One wonders just how big the jugs of wine were, because they drank almost four each. Meat was the largest item of expenditure and, although there was some poultry and a tiny amount of fish, veal was the main dish on the menu. This is surprising because it was still Lent. Ippolito certainly did not observe the fast as strictly on the road as at home. In fact a calf formed the basis of most of the meals Ippolito ate on the Italian leg of the journey. The animals were bought almost every day from local butchers by Zoane. The calf he purchased in Ferrara just before their departure on Monday, 13 March, had to be left behind because of a dispute over the price, and Ippolito had to make do with fish and lamb that first night. On Tuesday evening in Modena, Zoane bought two more calves, one of which was taken to Reggio in a specially hired cart, and he bought a third in Reggio on Wednesday. The normal Friday fast was observed that week at Fiorenzuola where they ate fish, but Zoane was out shopping for the usual calf again on Sunday in Voghera, on Monday in Alessandria and on Tuesday in Asti. The calf Zoane bought in Alessandria was quite small and had to be augmented with some veal supplied by the innkeeper.

Voghera, 19 March

Ippolito, and others who liked it, ate salad every day, usually bought by Zebelino or Gasparino, though sometimes it was supplied by the innkeeper. At Alessandria and Asti they bought leeks, onions and herbs to make soup. Eggs also featured very prominently. Ippolito and the men eating with him consumed over 200 eggs in the six days it took them to travel from Fiorenzuola to Saluzzo. Most days Zoane also bought delicacies. In Fiorenzuola he found twenty-four freshwater crayfish, which were carted all day in a sack to be eaten that night at Castel San Giovanni, and he bought oranges in Castel San Giovanni and Alessandria. In Asti he found raisins and four eels – probably not as good as those back home in Ferrara. Zoane was also responsible for maintaining stocks of the non-perishable goods which they carried on the journey – staples such as sugar, flour, rice, lard and various other sorts of cooking fats, candles, cheese and oil. By the time they reached Voghera he had accumulated so much that Pierantonio had to buy a horse (an old hack which cost 8 scudi, plus a small sum to pay the agent who negotiated the deal), as well as baskets to carry it all.

Dinner at The Cock in Voghera

A page from Zoane da Cremona’s ledger, signed at the bottom by Guarniero the steward

Town |

Value of 1 scudo |

Ferrara |

£3 10s |

Modena |

£3 16s |

Reggio |

£5 13s |

Fiorenzuola |

£3 15s |

Castel San Giovanni |

£5 12s |

Voghera |

£5 10s |

Alessandria |

£5 10s |

Asti |

£5 12s |

Carmagnola |

85 grossi |

Exchange rates

Zoane da Cremona’s evenings were particularly onerous. In addition to shopping, he also had his accounts to complete. His first task was to establish the exchange rate between the gold scudo and the local currency. If funds were running low, he had to find Tomaso Mosto who would advance him another 50 or 100 scudi (and then record this advance in his own ledger). Each town had its own currency, methodically entered by Zoane at the top of every page of his ledger, and also its own system of weights and measures, which he did not enter. Most of these currencies were based on the same system of pounds, shillings and pence – £.s.d or lire, soldi and denari – which Britain only abandoned in 1971 (one lira was worth 20 soldi, or 240 denari). In Carmagnola and Saluzzo the currency was decimal, with 100 grossi to a local ducat.

Zoane detailed all his purchases of food for the evening meals and the stores he bought for the journey in his ledger. He also recorded the sums he paid to the falconers for the pigeons and hens they needed to feed their birds, as well as the money he handed out to Pierantonio and Bagnolo to cover what they needed for the stables (Panizato got his funds directly from Tomaso Mosto). Each morning Zoane had to visit the inns where the household had stayed, check the bills and pay the host for dinners, accommodation and stabling. He also noted the tips to women, in the plural the night they stayed in Asti, just the one in Carmagnola. All the prices were recorded in the local currency. At the bottom of each page Zoane totalled his expenditure and then converted it back into scudi, listing the extra sums, in their original currencies, on a separate page. He was meticulous and neat, and astonishingly good at arithmetic – Ippolito had been very fortunate in his choice of purveyor.

Travelling at this leisurely pace, with an entourage the size of Ippolito’s, was inevitably extremely expensive. The payments listed by Zoane come to over 560 scudi, a sum which would have covered half the annual salary bill for the men travelling to France with Ippolito. Moreover, Zoane’s ledger only tells us part of the story. The expenses incurred by other household departments were recorded by Tomaso Mosto, though his ledger for 1536 has not survived. In addition to the sums he advanced to Zoane, Mosto gave money to Assassino and Zudio to pay for Ippolito’s laundry, to Jacomo da Parma for the pages and to various members of the household for their incidental expenses. He also recorded the substantial sums Ippolito gave out in alms to the poor and tips to dancing girls, gate-keepers and ferrymen. On a similar journey in 1540, Mosto’s expenditure added another 300 scudi to the cost of travel.

However, Zoane da Cremona’s book is very informative about the cost of inns, stabling and food. Ippolito spent an average of 38 scudi a day over the six days he took to travel from Fiorenzuola to Saluzzo, each night in hotels. This was more than the annual salary he paid either Vicino (31 scudi) or Zoane da Cremona (34 scudi). Take the night in Voghera again.

The total cost of housing and feeding the party for the night at Voghera came to 37 scudi, close to the average, but this does not include the 8 scudi which Pierantonio had to spend on the horse that was needed to carry the household stores. Horses were a major expense. Not only did they have to be stabled, they also had to be fed, which added almost twice the sum to the bill. The cost of each animal per night was more than a week’s wages for a stable boy and, significantly, only slightly less than the average Ippolito spent on food and accommodation for each of his men. Even so, by our standards, the cost of a night’s accommodation was cheap: there are few hotels in Italy that charge as little as the equivalent of 2 kilos of ordinary stewing steak for dinner, bed and breakfast.

Accommodation and food bills (in scudi) |

|

27 dinners and beds @ 10s each |

2.5 |

38 dinners and beds @ 8s each |

3 |

Food for Ippolito’s dinner party |

4 |

Cestarello and the ambassador’s party |

1 |

Extras |

1.5 |

Food bought in shops |

2 |

Breakfast for 50 mouths |

2.5 |

Food expenses to 23 stable boys and muleteers |

2.5 |

Stable bills |

|

Stabling 23 mules and 96 horses @ 5s each |

5.5 |

Fodder |

10.5 |

Cestarello and the ambassador’s party |

1.5 |

Other expenses |

0.5 |

Total |

37 |

currency: 110 soldi = 1 scudo |

The cost of staying in Voghera

Ippolito and his courtiers may have been uncomfortable, but for many of the household this was an experience few of them would have been able to afford themselves. For the footmen, dinner, bed and breakfast in Voghera represented four days’ wages; for Iseppo, Zebelino’s assistant in the credenza, who earned 7 scudi a year, it was nearly a week’s pay. The expense of travel was evident in the daily allowance Ippolito paid the stable boys, who were given almost ten times more than they received in Ferrara. For Ippolito himself there were financial drawbacks to a conspicuous display of wealth and prestige. There is plenty of evidence to show that innkeepers and others took advantage of the party. Innkeepers made a hefty profit from feeding travellers, and the host of The Cock in Voghera was no exception. The prices for the poultry he supplied for Ippolito’s dinner were considerably higher than they would have been in the market in Ferrara: 50 per cent more for a capon, 300 per cent more for a pigeon. Pierantonio was so incensed at being given short measures of fodder for the horses that he bought a new wooden basket in Alessandria the following night so that he could be sure of getting the correct amount.

![]()

The day the party arrived at Voghera had been an eventful one. Early that morning they had crossed into the duchy of Milan and, just outside Broni, they had been met by a company of imperial soldiers. The leader of the company was Ferrante Gonzaga, second-in-command of the imperial armies currently occupying Milan and a rising star in Charles V’s entourage. However, although he was on the opposite side of the political divide, Ferrante was also the son of Isabella d’Este and therefore Ippolito’s first cousin. Ippolito must have been relieved to recognize him. Their meeting was ‘most amicable’, as Ippolito reported that night in a letter to Ercole, but Ferrante’s news was not good. Francis I’s armies had now taken Turin, and Ferrante warned him that he had been ordered to lead his own troops to the border with Savoy. War might be only days away. Ferrante told Ippolito that he would need an official safe-conduct to get through the duchy, and he offered to escort one of his courtiers to Charles V’s Captain-General, Anton de Leyva. Count Niccolò Tassone went off to Leyva’s camp and returned to Voghera that evening with the safe-conduct. Leyva, he said, had been most polite and helpful, signing a pass that required the imperial armies to give Ippolito and his party any assistance they needed. It certainly helped to have the right connections.

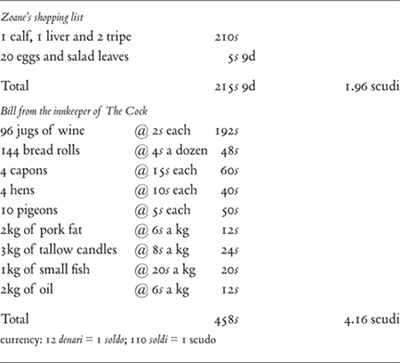

Ferrante also advised Ippolito to change his travel plans. Turin was no longer safe and, as the usual passes across the Alps were now full of soldiers, he had to find an alternative. There were three routes that most travellers used to cross the Alps in the sixteenth century: up the Val d’Aosta to the Petit-St-Bernard Pass (2,146 metres) or through the Susa valley from Turin to either the Mont-Cenis (2,083 metres) or the Montgenèvre passes (1,850 metres). The safest option available to Ippolito was to travel south-west to Saluzzo and take the Col d’Agnel, one of the smaller, less-frequented routes over the Alps. Vicino was sent on ahead to announce Ippolito’s arrival to the Marquis of Saluzzo. The change of route was bad news for a number of reasons. It was perhaps 90 kilometres further, which would add another three or four days to the journey. Worse, at 2,748 metres, the Col d’Agnel was considerably higher than the other passes, and in March it would still be covered with snow. It was difficult to see the Alps from Broni but, if the weather was good, the line of elegant white peaks stretching across the horizon would have been clearly visible the next day once they got to Alessandria. The mountains were not frightening at that distance, but as the party moved closer they must have become an awesome sight for men who had spent most of their lives on the lush Po plain.

They spent the night of Tuesday, 21 March, in Asti and the next day left the Turin road to travel south to Carmagnola. Once off the main road they needed guides – there were no signposts in sixteenth-century Europe, nor were there any road maps. On 23 March they reached Saluzzo, a city perched high on a hill overlooking the Lombard plain. By now the Alps were clearly visible, and they were dominated by the peak of Mont Viso (3,841 metres) which overlooked the Col d’Agnel. Entering the ornamental stone gateway, the party climbed up through the narrow cobbled streets of the town to the castle. Ippolito was warmly greeted by the Marquis, a distant relation and a captain in the French army – he was to be appointed Francis I’s lieutenant-general in Piedmont a few weeks later.

Staying as a guest in the castle may have been considerably more comfortable than the hotels Ippolito had just experienced, but it was not much cheaper. It was standard good manners to tip the staff who had looked after you during your stay. This involved tips of 1 scudo each to all the cooks, the credenzieri, the sommelier and the other dining staff, and the same amount to the each of the musicians and buffoons taking part in the entertainments. The tips Ippolito gave out at Saluzzo were recorded in Mosto’s missing ledger, so we do not know how much he actually spent, but it was unlikely to have been much less than the average of 38 scudi he spent at an inn.

The court at Saluzzo was much smaller than that at Ferrara, but it had a reputation for excellent musicians, and Ippolito and his courtiers looked forward to several pleasant evenings. There were also other guests staying who had been forced by the impending war to take the Col d’Agnel. One was Guillaume de Dinteville, a courtier of Francis I, who was on a diplomatic mission to Venice (his brother Jean was one of the French ambassadors painted by Holbein, a picture now in the National Gallery in London). Another was Galeazzo Ariosto, one of Ercole II’s courtiers, who was travelling to France with messages for Francis I and who joined Ippolito’s party. Reassured by Dinteville that the pass was open, Ippolito wrote a short letter to Ercole on 24 March, which he gave to Dinteville to take to Ferrara, to say he would be leaving the next day. But once again he delayed his departure. Perhaps the old reluctance had returned, or he might have been having fun, but the most likely reason must have been the weather. He would certainly have been advised to avoid the Col d’Agnel in a blizzard.

Ippolito finally left Saluzzo on Sunday, 26 March, intending to spend that night at Sampéyre, and Monday at Chianale, before crossing into France. Early on Sunday morning, a small advance party set out, consisting of Galeazzo Ariosto, Vicino and another squire, Ascanio, together with their three servants, three spare horses and a guide provided by the Marquis. Ascanio was to organize accommodation for the party at Sampéyre and Chianale, but Vicino and Ariosto were to carry on across the Col’Agnel, taking the spare horses in case of accident. Vicino would then wait for the main party in the village on the other side of the pass and arrange lodgings there, while Ariosto continued on to Lyon to find Francis I and to announce Ippolito’s impending arrival. Ippolito and the rest of the party left Saluzzo later that morning, accompanied by a guide and by two wagons, one for the hay Pierantonio had bought in Saluzzo, the other to carry the flasks of wine thoughtfully provided by the Marquis. Pierantonio had spent nearly 60 scudi in Saluzzo, mending harnesses and stocking up for the journey across the Alps. Apart from the hay, he had also bought wine, fat, fodder and 140 horseshoes. One of the muleteers also needed new shoes. Zoane advanced him the money, deducting the sum from the muleteer’s wages.

View of the towering peak of Mont Viso from the road between Carmagnola and Saluzzo. The Col d’Agnel crosses the Alps just to the south of the mountain

The route from Saluzzo up the valley to the Col d’Agnel is a deceptively gentle climb. The party rode through wooded hills, the mountains looming ever higher in the distance. The horses were much slower now they had left the well-worn roads of the plain, while the sturdy mules plodded on at their usual 5 kilometres an hour. The hamlets through which they passed were more prosperous than most Alpine villages. Sampéyre and Chianale were small but their inhabitants were able to augment an otherwise meagre existence in an inhospitable region with income from travellers to and from France. But these villages were a far cry from the bourgeois affluence of Ferrara, or even Asti. When he finally found time to describe this part of the journey to his brother, Ippolito recalled with horror the appalling lodgings and the miserable skinny animals. In late March, with their stocks of winter food and fodder running low, it is difficult to imagine that the locals greeted this huge party with quite the same enthusiasm as had the innkeepers on the Po plain. The taverns – Sampéyre had only two – were small and the food basic. On the menu were goat, bread, cheese and wine. There were no fashionable vegetables, fruit or salad.

On the morning of Tuesday, 28 March, they crossed into France, the stable party travelling separately from the others, each group with their own guide. The journey was a nightmare. In his letter to Ercole, Ippolito listed the horrors of the pass: the inaccessible road, the banks of snow and the appallingly rocky terrain. The Col d’Agnel is awesome, even in a car in midsummer. The modern single-track tarmac road is used mainly by hikers, or cyclists keen to test their muscles and their nerves – buses and lorries are forbidden, and the road is only open from June to September. It snakes up from Chianale through a series of viciously steep hairpin bends, taking the traveller from 1,797 metres to 2,748 metres in under 10 kilometres. Perched at the top of the pass is a very narrow platform with stupendous views down into the valleys that fall sharply away on either side. Whatever the weather conditions when Ippolito crossed the pass, he would immediately have been aware that he had reached the summit when suddenly the exhausting climb was transformed into a treacherously steep descent and the horses began to slither their way down an icy road plunging through another series of sharp bends into France.

It was 16 long kilometres from the summit of the Col d’Agnel to the village of Molines-en-Queyras, where Vicino waited anxiously. Surprisingly, only one muleteer and his three mules got into difficulty crossing the pass and failed to arrive before nightfall. There do not seem to have been any inns in Molines. Vicino organized lodgings in thirteen different houses, with the animals in seventeen separate stables, some so small they could take only one horse. As on the Italian side of the mountains, the food was basic. Dinner consisted of bread, wine, eggs and two small calves. It was also expensive – the price of stabling the horses and mules was 10 per cent more than elsewhere in France, while wine cost twice as much.

![]()

The return to civilization is eloquently charted in Zoane da Cremona’s ledger. Rather than face another mountain pass, Ippolito decided not to take the quickest route but instead to head south to Gap, adding at least a day to the journey. There the party joined the main road from Nice to Grenoble. After the tiny hamlets of the Alps, the bustling town of Gap must have been a considerable relief. It was a Friday, a lean day. There had been no fish in the mountains, but that evening Zebelino managed to find two types of salted eels in the market, as well as herrings and anchovies, onions, almonds and cheese. He bought so much that it took a porter three trips to get all the food to the inn. From Gap onwards their diet consisted almost entirely of fish. It is difficult to tell whether this was because Lent was observed more strictly in France than in Italy, or because Ippolito himself was conscious of needing to adhere to convention now that he was abroad.

At Corps the following night, 1 April, they had a real feast. There were just three inns in the small town with rooms for the party – The Falcon, The Lion and The Three Kings. More than half the men were put up in private houses. Cestarello’s servants had to lodge at the blacksmith’s. Ippolito stayed at the Three Kings, where his dinner, which he must have shared with others, was organized by Guarniero. The ingredients supplied by the innkeeper included tuna, salmon, trout and 308 eggs. Zoane had also bought apples and salad, the first they had eaten since Saluzzo, a week before. For the first time too since Saluzzo, there were shops where one could stock up on essentials. Pierantonio bought 1,000 nails, a quantity that suggests there had been plenty of mishaps in the mountains. He also bought ingredients for a poultice for one of the mules and had two pack saddles mended. Jacomo took the pages’ shirts and other linen to the laundry and bought them some treats – sugar to make posset, almonds, candied plums and other sweets.

Ippolito reached Grenoble on Sunday, 2 April. Ariosto, who had been waiting for two days, had welcome news. The French court was hunting outside Tour-du-Pin, and the King was looking forward to Ippolito’s arrival. The party stayed in Grenoble for two nights, recovering from the ordeal of their journey across the Alps. Grenoble was swarming with soldiers but the goods on sale in the shops showed that they were once again in a prosperous city. Zoane bought raisins, oranges, spices such as saffron and cinnamon, parsley and other herbs, as well as salad ingredients and two hares (game was allowed during Lent). Many of the household were ill, including Cestarello and Mosto. Ippolito too may have been unwell because Assassino, the Master of the Chamber and not normally one to do the shopping, was reimbursed by Zoane for a Savoy cabbage and other ingredients to make an acquacotta, a light soup made from vegetables and water, and ideal for a delicate appetite.

France must have seemed strange to the household. For Zoane the clearest indication that he had left the mosaic of small states that made up Italy and was now in a large centralized monarchy, was the fact that the currency did not change every day, nor did the weights and measures. It must have made totalling up his accounts at the end of the day considerably easier – it certainly makes the ledger easier to read. One wonders what the party made of the language. Ippolito himself spoke good French, one of the languages current at the Ferrarese court, but Zoane had more difficulties. He italianized many French names, writing Georges as Giorgio, and Jean as Gian (though not as Zan or Zoane, as it would have been in the Ferrarese dialect). Similarily he Italianized local terminology – concierge became consergio, marons (the Alpine term for guides) became maroni. He must have read the inn names from their signs, because he described several hotels simply as ‘inns without signs’. Another surprising feature of life in France was the quantity of women trading as bakers, haberdashers and even innkeepers. The only females who had featured in Zoane’s books while they were in Italy had been laundresses and women tipped for their favours. France was also considerably cheaper than Italy. The average bill for the party for a night dropped from 38 scudi to 31 scudi. French innkeepers had a different system of pricing, charging separately for dinner, bed and breakfast, and the rates for stabling varied. However, they still charged extra for essentials such as firewood, candles and fodder, and they made a profit on the ingredients they supplied for Ippolito’s dinner – pigeons were twice the price they had been in Ferrara.

On leaving Grenoble on Tuesday, 4 April, the household divided. One party stopped at Voiron for the night while the other rode all the way to Tour-du-Pin 60 kilometres away. Ippolito himself took the easier option and stayed at Voiron with Romei, Provosto Trotti, Scipio d’Este and Cestarello, who was so ill that he had to be carried from Grenoble in a litter. Besian and Bresan the falconers also stopped at Voiron where they managed to lose one of Ippolito’s falcons. Mosto had recovered and was well enough to go to Tour-du-Pin, along with the rest of Ippolito’s courtiers, Guarniero, Vicino and the squires, Andrea and the cooks, Assassino, the valets, Moiza and Zudio. The Tour-du-Pin party stayed at The Angel and all ate together that night in the communal dining-room of the inn. There was a lot of work to do, preparing for Ippolito’s arrival at court, which had been fixed for the next day. Mosto had to unpack an outfit of suitably splendid clothes from the wardrobe chests, and make sure it was fit to wear. Assassino, Moiza and Zudio needed to perfume Ippolito’s gloves, wash his linen and make sure everything was ready to shave and dress Ippolito when he arrived in the morning. Guarniero and the cooks had an important meal to organize at The Angel, a lunch party for Jean d’Humières, the envoy of Francis I who was to escort Ippolito to the King. Ippolito must have left Voiron early on Wednesday morning and ridden the 34 kilometres to Tour-du-Pin in time to wash and change before Humières arrived. Lunch was impressive. Guarniero, or rather one of the cooks, had spent over 3 scudi on crayfish, oranges, almonds, figs, pullets and eighteen carp, which had cost nearly 2 scudi and were the centrepiece of the meal.

Ippolito and Humières left after lunch to ride out into the countryside where Francis I was hunting. Ippolito was escorted by twenty-six of his household, the minimum number needed to ensure that his entourage was appropriately impressive and to look after his personal needs. Most of the men were noble. He took ten of his eleven courtiers (Cestarello was too ill) and Francesco dalla Viola, his musician. With Assassino were Moiza, Zudio and one of the valets (the footmen were all left behind). Guarniero brought the cooks Andrea and Turco, Alfonso the carver, one of the credenzieri, Priete the sommelier and just one squire, Vicino. Mosto took one of his wardrobe assistants, and Zuliolo brought Panizato. Panizato’s main job would be to keep in touch with the rest of the household, who were having a well-earned rest in the inns of Tour-du-Pin. It was twenty-four days since Ippolito had left Ferrara, another world and a lifetime ago. As he rode out of the courtyard of The Angel, newly shaved and smartly dressed, he must have been excited, but he could not have anticipated how the next three hours would determine his future.