5

Domestic Affairs

IPPOLITO TRAVELLED A long way in 1537. By the end of the year he had ridden 2,500 kilometres and seen more of France than most of the country’s inhabitants. He celebrated New Year in Paris, spent the spring with the French army fighting in northern France and then returned to Fontainebleau for the summer. In the autumn he rode south to Lyon and crossed the Alps into Italy, accompanying the King on his royal progress through Piedmont, before returning to France and riding south-west to Montpellier, not far from the border with Spain, where he spent Christmas. He sampled the sophistication of a royal capital, the excitement of violent but victorious battle, the luxury of a magnificent royal villa and hunting park, and, twice, the discomfort of mountain travel. It is hard to imagine a greater contrast to the regular routine and provincial perspectives he had left behind in Ferrara. Nevertheless Ferrara was home, and the source of the wealth that enabled him to live, in some style, at the French court. Although the ledgers kept by his household in France in 1537 no longer exist, the account books charting the management of his properties in Ferrara that year have survived. These ledgers were kept by Jacomo Filippo Fiorini, ex-painter and ex-guardian of Ippolito’s wardrobe, who had been left in Ferrara to run Ippolito’s affairs during his absence. The scope of Fiorini’s job, together with his accountant’s eye for precise detail, make these ledgers a mine of information, providing fascinating glimpses into the everyday lives of all sorts of people with whom Fiorini had dealings – not just merchants, shopkeepers and artisans, but also bargemen, carters, casual labourers and even the destitute. The ledgers also tell us a lot about Fiorini himself, and his relationship with Ippolito.

One cold morning early in February 1537 Fiorini gave 345 kilos of wheat (old wheat, worth about 5 scudi) to a widow called Domicila di Sabadini. Her newly wed daughter had been abandoned by her husband, a builder, because Domicila had not been able to pay the agreed dowry. ‘I was moved by compassion,’ Fiorini wrote, ‘and because God will reward Monsignore [Ippolito] and safeguard him from ill fortune, I gave her 20 stara of the old wheat so that this young girl can return to the world with honour.’ This was not a very large amount of grain – that same day Fiorini gave 23 stara of wheat to Provosto Trotti, one of Ippolito’s courtiers, as the monthly allowance Ippolito provided for him and his two servants. One hopes that Domicila, her deserted daughter and even the mercenary son-in-law all benefited from Fiorini’s gesture. Fiorini certainly believed that Ippolito would gain from it, when God honoured his side of the bargain. But the episode reveals much about Fiorini himself, not least the meticulous way in which he recorded the details to justify this unexpected item of expenditure. It illustrates his basic decency and loyalty, his care for Ippolito’s welfare and how his master looked in the eyes of the world, and also his unconscious recognition of the unfairness of some of the laws that governed the society in which he lived. It was rare for Fiorini to allow a personal note to creep into his ledgers – he was much more at home dealing with sums rather than emotions.

Ippolito had been fortunate in his choice of steward (his title was factore, a word that translates directly to the Scottish ‘factor’). Fiorini was hard-working, conscientious and honest. He lived in rooms in Ippolito’s villa at Belfiore, on the northern edge of the city, and was at work in his office in the Palazzo San Francesco six days a week, often seven. During 1537 he worked on thirty-six out of the fifty-two Sundays and on many major Church holidays, including Easter Day and Christmas Day; he even worked on 23 April, the day most citizens of Ferrara took to the streets to celebrate the feast of their patron saint, St George. Every transaction, income or expenditure, was minutely detailed in his notebooks in his precise and legible handwriting. On the first day of every month he started a new notebook – A4-sized exercise books bound in blue card – carefully writing the page number in the top right-hand corner of each spread. He began by listing Ippolito’s income on the first page and then left five or six empty pages before starting on the expenditure. He made remarkably few errors, which is impressive given the complexity of some of the transactions, though he did occasionally enter an expenditure item under income, or vice versa, and had to cross the entry out, with firm clear lines, before inserting it correctly.

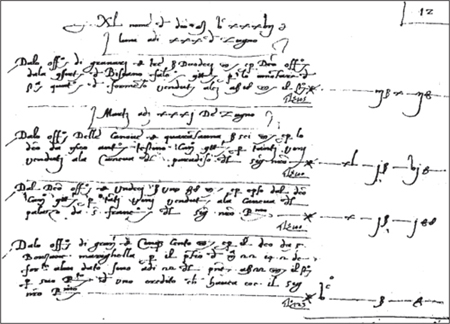

Each entry follows the same formula. Fiorini recorded the date, the people involved, the sums received or paid out, the goods or services involved, often an explanation of why the transaction had taken place and, where relevant, the prices. If he found bookkeeping boring and repetitive, it does not show. His assistant, Tomaso Morello, then collated the cash transactions from Fiorini’s notebooks (ignoring some of Fiorini’s detail) into a large leather-bound ledger to provide neat final accounts. These were audited by the ducal accountants, one of whom was Tomaso’s father Piero, who had worked on Ippolito’s books since 1524 and had doubtless been instrumental in getting Tomaso this post. Both father and son turned out to be crooks. Piero had managed to extricate himself from a charge of fraud earlier in his career in the ducal administration and only escaped a death sentence by persuading Ippolito’s grandfather, Ercole I, to pardon him. He got his job back but the old Duke’s trust in the family proved seriously misplaced. In 1543 Tomaso was arrested for fraud. While he was incarcerated in the castle prisons – where he was fed at Ippolito’s expense – Piero, who was still working at the age of 74, decided on drastic action and set fire to the ledgers in his office in the castle. During his trial he was forced to confess that he had been embezzling ducal funds. I have not found any evidence of dishonesty in the ledger Tomaso compiled in 1537 but he did make some very bizarre mistakes: there is a 31 June for example, and in mid-March he got muddled with the days of the week, following Friday, 23 March (which was correct) with Thursday, 24 March. These were not the sort of errors that Fiorini would make.

Tomaso Morello’s ledger, showing his entries for30 and31 June (xxx and xxxi de Zugno)

![]()

Fiorini’s job carried considerable responsibility. He was not just Ippolito’s bookkeeper but also his treasurer. It was Fiorini who received the income from Ippolito’s assets in Italy, and paid all his bills. He did Ippolito’s personal shopping in Ferrara and arranged for these purchases to be sent to France. The upkeep of both the Palazzo San Francesco and Belfiore were in his charge, as were the staff who had remained behind in Ferrara: Marcantonio the cellarman, Carlo del Pavone the larderer, Francesco Salineo the flour official, Francesco Guberti, who managed the wood store and acted as Fiorini’s personal assistant, Antonio da Como, who had been Ippolito’s credenziero and was now a general factotum, Francesco the gardener at the Palazzo San Francesco, and Tomaso, who looked after the gardens and the poultry at Belfiore, as well as all the men working in the stables, and the kennelmen and falconers at Belfiore. Fiorini also paid wages and expenses to the families of several members of the household who were away in France, such as Andrea the cook, and to staff who had returned to Ferrara, including Moiza, Ippolito’s personal barber, who arrived back in June 1536 and continued to earn a salary until the end of 1538.

However, Fiorini’s main responsibility was the financial management of Ippolito’s estates, stores and granaries (Ippolito owned one granary and rented another at the Po wharves). He had to keep track of every sack of grain, cart of wood, bale of hay and barrel of wine sent to Ferrara. He agreed rates of pay with the bargemen, who shipped the goods, and with the carters and porters, who moved each load from the wharves. Fiorini also had to monitor every sale from each of Ippolito’s stores, and to record all in-house transactions, such as the tallow candles taken from the larder to light the cellars, the jugs of oil from the larder to light the lamps in the stables and the brooms the stable boys used to sweep them clean.

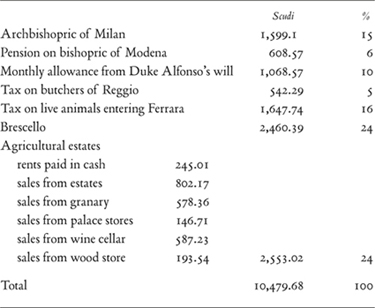

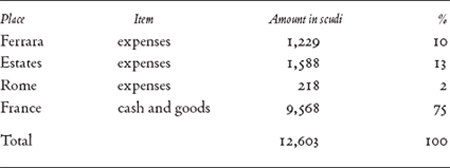

Ippolito’s income in 1537 came from various sources, all of which had family connections. He had acquired the archbishopric of Milan from his uncle, Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, when he was only 9. Under the energetic administration of Paulo Albertino, his agent in the city, Milan produced a substantial sum in 1537 – the full impact of Charles V’s sequestration of his income would not be felt until the following year. The pension Ippolito received from Modena was paid regularly every six months by the Bishop of Modena as part of an agreement with the Pope to compensate Ippolito, who had been refused papal permission to inherit the bishopric after his uncle died. One of the agricultural estates, Bondeno, had also been inherited from his uncle, but the rest of the income – say two-thirds – came from the ducal properties bequeathed to him in his father’s will. In addition to the monthly cash allowance his brother was obliged to pay him, Ippolito received the taxes raised on the butchers of Reggio and on all live animals entering Ferrara. He shared the income from the latter with his stepmother Laura, and they divided the cost of building an office – more like a booth – on the bridge into the city, where the tax was collected. The most lucrative item in his portfolio was the town of Brescello, which provided nearly a quarter of his income. This prosperous little centre close to the duchy’s north-western border with Mantua and Milan had a thriving cloth industry, though it is now more famous for its football team.

Ippolito’s cash income, 1537

In his ledgers, Fiorini used the standard silver-based currency of Ferrara – lire, soldi and denari (1 lira = 20 soldi = 240 denari). He also had to deal with a wide range of foreign currencies, and their fluctuating exchange rates. Ippolito’s allowance from Duke Ercole and the tax on live animals entering Ferrara both arrived in Ferrarese coinage, but the butchers’ tax from Reggio was paid in local ducats (worth £3 13s each). Fiorini also received Italian scudi from Brescello (worth £3 10s each) and money from Milan, which sometimes came in lire imperiali (exchanged at £5 11s to a scudo) but also in various types of scudi (Milanese and Genoese, and even French). Transporting money in sixteenth-century Europe was a necessary but risky business. Fiorini preferred to settle bills directly with Ippolito’s creditors, but he regularly had to pay these bills to their servants or relatives – and he was careful to note precisely the relationship between the creditor and the recipient in his ledgers. On one occasion he trusted a barge boy with the salary Ippolito owed to the chaplain at Bondeno, but this was unusual. The income from the estates was carried by Ippolito’s agents, or trustworthy substitutes, on the relatively short journeys across the Este duchy and delivered to Fiorini in weighty leather pouches. The dangers were greater outside the duchy. Paulo Albertino rarely sent cash from Milan but deposited Ippolito’s income with Ferrarese bankers in the city who then sent credit notes to Fiorini which he could exchange in Ferrara. There was no question of sending large amounts of money to Ippolito in France. Ippolito got through over 7,000 scudi during 1537, which he withdrew as he needed from the Lyon agent of his sister-in-law, Renée of France, who was then reimbursed in Ferrara by Fiorini.

Ippolito’s estates in the Este duchy

The agricultural estates at Bondeno, Fóssoli and Pomposa together with his property in the Romagna made Ippolito a substantial landowner. Bondeno, which he had inherited in 1520, was a small parish with rich farming land about 20 kilometres west of Ferrara. The huge estate of Pomposa, formerly attached to the abbey of Pomposa, gave Ippolito land east of Ferrara across the fertile soils of the Po delta to the Adriatic coast. In the Romagna he owned woods and three highly profitable mills at Lugo, Bagnacavallo and Consélice. Fóssoli, the smallest of the estates, lay 80 kilometres west of Ferrara. It had been part of the old imperial fief of Carpi until 1530, when Charles V had evicted the Carpi family and given the state to Duke Alfonso – Ippolito’s ownership of Fóssoli cannot have done much to improve his relationship with Cardinal Carpi.

The estates were all managed by local agents. The agent at Bondeno was Palamides de’ Civali, who administered not only the farm but also the church, where he paid salaries to the priests and bell-ringers. Palamides reported directly to Fiorini but the men running the other estates were supervised by Ippolito’s land agent, Bigo Schalabrino. The name Bigo was the local way of shortening the name Ludovico, or Lewis – his name translates as Lew Sly, an intriguing moniker for a man whose job was to keep a watchful eye on the bailiffs. Pomposa was so large that it required three bailiffs, based at each of the main towns of the estate, Baura, Migliaro and Codigoro. They needed Bigo’s authorization for any major item of expenditure, such as shearing the sheep or paying wages to the workmen repairing buildings on the estates. Bigo spent a lot of his time on the road. He travelled from Ferrara to Fóssoli most months to collect the produce and cash amassed by the bailiff since his last visit – a 160-kilometre round trip – and then on to Pomposa, another 54 kilometres each way, where he spent a day with each of the bailiffs there.

About 10 per cent of Ippolito’s income from the estates came from rents, though this figure is slightly misleading as some of the rents were paid in goods, which were then sold. Leases for plots of land or houses were drawn up by Ippolito’s lawyers and each lessee signed the witnessed contract which laid out precisely how much rent was due and when it had to be paid (the lessee also paid a tax for the privilege of signing the contract). Rents were invariably paid on the feasts of the Annunciation (25 March), St John the Baptist (24 June), St Michael (29 September) and the Nativity – exactly the same as the old English quarter-days of Lady Day, Midsummer, Michaelmas and Christmas. Some of the men who rented Ippolito’s land were officials at the ducal court, but most were artisans – barbers, goldsmiths, painters, tailors and butchers – who used their holdings to provide fresh food for their families in town. Some of the plots must have been very small judging by the modest rents: a sack of wheat, three hens or just one capon. Larger plots were leased for money by men like the barber who paid 10 scudi each year for fields at Bondeno or the lawyer who paid an annual rent of 12 scudi for land at Pomposa. Ippolito also owned the inn at Goro, a small town on the Adriatic coast near Pomposa, which he rented out to the innkeeper, appropriately named Andrea Bonamigo (Andrew Goodfriend), for 31 scudi – when the inn burned down in a fire in 1539, it cost Ippolito 23 scudi to rebuild it.

The bulk of the income from the estates came from the sale of produce. Some of it was sold directly on the estates, but most was marketed from Ferrara. All the wine from the cellar at the Palazzo San Francesco, the wood from the store and the grain from the granary came from the estates. Wheat was the largest grain crop grown at Bondeno and Pomposa where it flourished on the rich alluvial soils of the Po plain. This was lush agricultural land, not the thin, dry stony soils where olives were cultivated – Ippolito had to buy his olive oil from the Marche and Puglia, further south. His estates also grew barley and occasionally rye, as well as cheaper grains such as millet, spelt and vetch. Most of the barley, millet and spelt was used as fodder for Ippolito’s horses, though the poor ground all these crops, as well as legumes and vetch, to make bread – only the rich could afford white bread made from wheat. The estates produced large quantities of legumes, particularly chickpeas, lentils, beans and broad beans, rotating these crops with wheat (in an age before fertilizers, legumes had the practical advantage of restoring nitrogen to the soil). Flax and linseed were grown at Bondeno and Pomposa, and all the estates produced hay and straw for Ippolito’s horses, as well as wine for his cellars. At Fóssoli, where the land was poorer, the main crops were spelt and sheep. Pomposa also supplied livestock – poultry, cattle, pigs and lambs – and the estate’s extensive woods produced large quantities of logs for Ippolito’s ovens and fires as well as timber for building. The wood was also used as fuel for a profitable kiln at Codigoro which produced bricks and tiles. Even the twigs were useful, bound into brushes and brooms which were sent to Ferrara to clean the Palazzo San Francesco.

All the farming was done by Ippolito’s workers – they are called workers (laboratori) in the ledgers, not peasants. They planted and harvested his crops, ploughed the land, tended his sheep and cattle, cut the hay, felled the trees, chopped the logs and made the brushes and brooms. However they were not agricultural labourers in the modern sense of the term, nor did they have the independence of tenant farmers. Ippolito did not pay them wages but he did provide them with seeds and with accommodation in houses on the estates, which he was obliged to keep in good repair. He took a proportion of everything they produced. The term used in the ledgers is a tithe (decima), literally a tenth, derived from the 10 per cent that the Church originally deducted from all crops grown on its land. By the sixteenth century, however, the decima was a euphemism – in practice it was often 50 per cent, the amount Ippolito claimed on the sale of wool and lambs from Pomposa, although the percentage varied for other crops. The workers also had to pay Ippolito seasonal dues – for the workers at Migliaro this meant 100 eggs at Easter and a pig at Christmas. The system was not quite as iniquitous as it sounds. It was certainly unfair by modern standards, but levels of poverty were far worse on the city streets of Ferrara. There is detailed data on what the workers at Pomposa harvested in 1540, how much was taken by Ippolito and how much each worker retained. Marti Bolgarello, one of the eight men working on the farm at Migliaro, was left with grain and legumes worth 23 scudi, while one of his neighbours, Antonio Maria Trova, had crops worth 67 scudi. For both men, this was enough to feed themselves and their families, and Antonio Maria would have had a surplus to sell. However the documents are silent about what happened when a worker became too old, or too ill, to work.

![]()

The new year in Ferrara began on 1 January – unlike Florence and several other cities in sixteenth-century Italy, where it did not begin until 25 March, the feast of the Annunciation – and winter was the season for feasting at all levels of society. While Ippolito banqueted and jousted in Paris, his staff at the Palazzo San Francesco and the workers on his estates in the countryside also celebrated. January and February were relatively quiet months on the work front both in the city and on the farm. As the agrarian calendar carved on one of the portals of Ferrara Cathedral showed, January was the month when the peasant rested from his labours and ate and drank his way through New Year, Twelfth Night and Carnival, while February was the month to stay indoors in front of a blazing fire. This was good advice – the winter of 1537 was particularly cold.

Much of Fiorini’s work was regular and routine. Every few months he settled Ippolito’s debts with Renée, paying huge sums to her treasurer to cover what Ippolito had withdrawn from her agent in France – he paid 2,000 scudi to the treasurer on 22 January. Each week he paid alms of 12 soldi (worth 2 scudi a year) to the nuns of Corpus Domini, an allowance that Ippolito had arranged for the convent of which his sister, Eleonora, was Abbess. Every fortnight or so he handed out alms on Ippolito’s behalf to various churches to care for the poor – the amount was calculated at a daily rate. Most weeks cartloads of fodder for the horses were delivered to the Palazzo San Francesco – millet, spelt and bran, collected from the granaries, and hay and straw, brought over from the barns at Belfiore. There were the sales from the granary and the wood store to enter, as well as the money received from Marcantonio the cellarer for the sale of wine from the palace cellars. On Saturdays Fiorini paid the weekly wages to Andrea the painter and his team of decorators, who were now refurbishing some of the reception rooms in the Palazzo San Francesco. He also had to remember important Marian festivals and arrange for expensive beeswax candles to be sent from the larder to the church at Bondeno, which was dedicated to the Virgin. The first of these was Candlemas, 2 February, now known as the feast of the Purification of the Virgin but described by Fiorini as Santa Maria delle Candele. The priests held a special service to celebrate the feast, decorating the church with the white candles that Fiorini had bought in Venice the previous December – the church must have looked very pretty, and the beeswax would have smelt particularly sweet to the congregation, who were used to the fatty animal odour of the tallow candles they burned at home.

January, showing a man with a large Jlagon of wine, from the Door of the Months in Ferrara Cathedral

At the beginning of every month Fiorini was preoccupied with paying salaries and expenses. All ordinary members of the household, including the stable boys and the staff running the palace, received monthly salaries and, because meals were not provided in the communal dining-room while Ippolito was in France, they were given a food allowance calculated at 10 denari a day (just under 4¼ scudi a year). There were salaries and expenses to be paid to the wives of those members of the household who were away in France. The three courtiers who had returned to Ferrara – Niccolò Tassone, Scipio d’Este and Provosto Trotti – also received their salaries from Fiorini but, instead of the standard sum for food, they were each given a variable allowance based on a daily ration of ½ kilo of veal, beef or fish per mouth per day for themselves and their servants. They were all paid for the same quality of fish on feast days but on meat days the courtiers’ rates were based on expensive veal while their servants only got cheap beef. However, these men were much better fed than the rest of the household – the courtiers’ allowance was over 8½ scudi a year, while a servant’s allowance came to nearly 7 scudi. Fiorini must have had tables to help him work out the mathematical intricacies of these expenses. The final sum depended on the number of days each courtier was in Ferrara, how many servants he had, and the amount of Fridays and Church feasts in that particular month.

One of Fiorini’s tasks that January was to organize the purchase and dispatch of several crates of goods that Ippolito had requested (see Chapter 4). The crates were to leave on 29 January with Alberto Turco, who was travelling north to Amiens, in midwinter, to take up his post as Ercole II’s new ambassador in France. Fiorini got a carpenter to make up the crates and then had them coated in pitch. He packed four new linen shirts, which Sister Serafina at San Gabriele had embroidered, using black silk from the wardrobe given to her by Fiorini, and a lot of materials. Fiorini had been to Venice during December and had spent 363 scudi on 175 metres of velvets and satins which Ippolito had requested. Ippolito might have trusted Fiorini to buy good-quality materials but real luxury goods were outside his steward’s area of expertise. The two sets of gold embroidered sleeves and two gold and silver collars alla francese, which Ippolito wanted as presents for ladies at the French court, were all commissioned in Mantua by one of his courtiers, Niccolò Tassone, who was reimbursed by Fiorini. Tassone also bought special boxes to protect these delicate and valuable items (one of the collars was not finished in time and had to be sent on later). Similarly it was Tassone who ordered Ippolito’s arms and armour, another area with which Fiorini would have been unfamiliar. He commissioned two swords and scabbards from Costantino, a swordmaker who did a lot of work for the ducal court, and bought another in Milan, for 8 scudi, all of which were sent off with Turco. Also in the crates were two violins, which Tomaso Mosto had commissioned on Ippolito’s behalf from the ducal workshops before they had left for France the previous March.

January brought other problems for Fiorini, in particular, a spate of petty thefts by boys who had got into the rooms upstairs in the Palazzo San Francesco. To deter further thievery he decided to install a strong gate reinforced with iron bars and a heavy lock at the top of the main staircase of the palace. There were also several outstanding bills to settle. Most suppliers were paid on delivery, but the shopkeepers and small businessmen who were used regularly were invariably paid in arrears. One butcher had to wait over four years to be paid for a calf he supplied, but this delay was exceptional (there was a long dispute about how much it was worth). In January 1537 Fiorini paid the men who had supplied and killed the pigs for the hams, which had been made in December, the farrier’s bill for the horsehoes supplied since September, the bargemen’s bills for transporting the harvest the previous summer, the saddler’s bill dating back to June and one from a cloth merchant, who had still not been paid for materials he had supplied before Ippolito left for France in March 1536.

The season of feasting ended abruptly with the start of Lent which, in 1537, began on 14 February. Fiorini took a holiday to celebrate the last day of Carnival but he was back at his desk the next morning. His ledgers soon reveal the impact of the shift from indulgence to denial that marked the onset of Lent in sixteenth-century Europe. Fiorini doubled the daily quantity of coins he gave to the churches for the poor, who suffered increasing hardship during the winter months. The ban on eating meat during Lent, which must have had an immediate impact on Fiorini’s stomach, also affected Ippolito’s income. The revenues from the tax on live animals dropped sharply from a high point of 244 scudi in January to an annual low in February of 57 scudi. Fiorini also had more wages to hand out – Andrea the painter and his team decorating the Palazzo San Francesco had worked only fourteen days during January but were paid for twenty days the following month. However, there were advantages – Lent must have simplified Fiorini’s task of working out the food allowances for the courtiers and their servants, who would now be given an allowance based on fish every day until Easter.

![]()

Towards the end of February – while Ippolito was travelling through the mud and rain in northern France – spring arrived in Ferrara. As the weather improved and the days lengthened, the blossom came out on the fruit trees at the Palazzo San Francesco, and green shoots appeared in the vegetable garden. On 24 February, the gardener had enough salad to take down to the Saturday market in the main square in Ferrara – his first trip that year – and he bought himself a new basket for the occasion. It was also the beginning of the year’s work on the farms. The shepherds started to wean the lambs that had been born at Christmas and fatten them for the Easter market. Bigo took 17 kilos of vetch over to Codigoro for the lambs on 28 February, together with another 8 kilos for sowing. This was also the season for pruning the vines and for planting legumes. By the end of February Fiorini was recording the dispatch of sacks of chickpeas, broad beans and other pulses from Ippolito’s granaries to Pomposa and Bondeno for sowing (the wheat and other grains had been planted in October). In early March he sent linseed to Migliaro for Marti Bolgarello, Antonio Maria Trova and the other workers there to plant for the summer’s flax crop. Another sign of spring was the renewal of traffic along the canals and waterways of the Po delta, a welcome sight for the porters and carters waiting at the wharves, who relied on this traffic as their main source of income. Jacomino Malacoda (or as we might say, Jimmie Badtail), whose barges had lain idle for most of December and January, arrived at the wharves on 16 February with a load of broad beans and chickpeas, returning to Bondeno with his craft laden with planks for building. The broad beans and chickpeas were sent on to Pomposa for sowing, carried by other bargees who had made their way upstream to Ferrara laden with firewood. Nearly 100,000 logs, mostly from the woods at Codigoro, arrived by barge for the store at the Palazzo San Francesco during March and April.

Transport was labour-intensive and expensive. Fiorini’s ledgers contain extensive data on the transport of produce from Ippolito’s estates, not only the names of all his bargemen, and the prices they charged, but also the rates charged by the porters and carters who moved the goods from the wharves. Every cargo had to be unloaded from the barges by hand, loaded on to carts, carted to the stores, unloaded and finally stacked. The cost of transporting one cart of firewood (375 logs) from Codigoro to the store at the Palazzo San Francesco came to nearly 40 per cent of its market value, while the cost of bringing a cart of straw from Bondeno to the barns at Belfiore amounted to over 60 per cent.

Fiorini had to record the arrival of the goods under income, and each of the payments for the various stages of transport under expenditure. The bargemen usually worked on contract. Most of the crops from Bondeno were brought by Jacomino Malacoda, whose family had been moving Ippolito’s harvest ever since he inherited the estate – Jacomino’s bill for 21 scudi for the 1536 harvest had only been settled by Fiorini a month earlier. We do not know the size of his barges but they regularly carried loads of 5 tonnes and more, hauled slowly along the Po to Ferrara – a 20-kilometre journey that must have taken the best part of a day. There were also regular bargemen on the Codigoro and Migliaro runs, who charged a higher rate as they had much further to travel. Although Baura was only 10 kilometres from Ferrara, Migliaro was 40 kilometres downstream, while the distance to Codigoro was 54 kilometres. Porters and carters were casual labourers and were invariably paid on the day, as were the unfortunate men who had the unenviable task of counting the logs in each shipment, often as many as 10,000.

A cart of wood from Codigoro (market value 47 soldi 3 denari) |

||

Barge from Codigoro |

9s 4½d |

|

Counting and loading logs into carts |

5s |

|

Carting logs to wood store |

3s |

|

Stacking logs in wood store |

1s 4d |

Total 18s 8½d |

A cart of straw from Bondeno (market value 22 soldi) | ||

Barge from Bondeno |

5s 6d |

|

Loading bales into carts |

1s 6d |

|

Carting to Belfiore |

5s |

|

Stacking in barn |

1s 6d |

Total 13s 6d |

Transport costs

March was a particularly heavy month for Fiorini. He took just two days off and covered twenty-three pages of his ledger listing items of expenditure – he had only used fourteen in February. The week leading up to Easter – which fell on 1 April in 1537 – was particularly heavy and accounted for eight of these pages. Fiorini and the other staff at the palace were so busy that no one was allowed to go home for lunch – they were fed instead, at Ippolito’s expense, on bread and cheese from the larder. One of the days Fiorini took off was Sunday, 25 March, which, in 1537, was not only the feast of the Annunciation but also Passion Sunday. The church at Bondeno needed special decoration for both feasts, as well as for Easter Sunday. Fiorini sent 9 kilos of wax candles (ten large and thirty medium) to Palamides to ornament the church for the Annunciation, a substantial quantity to mark the principal Marian feast in the Church calendar. He also reimbursed Palamides for buying sixteen olive branches, which were hung in the church on the same day to mark Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem. The following Sunday, Easter Day, the church was decked out yet again – this time with a rather elaborate and expensive arrangement of wax candles, topped by a cross, to symbolize the Crucifixion, and a statue of the Virgin, to mark the dedication of the church. This arrangement had been specially ordered by Fiorini from Venice and, if the price is any guide, it must have been impressive – it cost 2½ scudi, a sum which would have represented twenty days’ work for any carpenter in the congregation or provided seventy chickens for his dinner table. Fiorini also had the first of the year’s rents to record, which were due on the Annunciation (Lady Day) – none had arrived by 25 March, but they started to roll in from 5 April. The Easter eggs due from Marti Bolgarello and the other men working at Migliaro – 100 from each of them – all arrived on time, though the bailiff had already sold Antonio Maria Trova’s eggs locally and sent the cash instead. Most of these eggs were given to the painters redecorating Ippolito’s apartments at the Palazzo San Francesco to mix their colours.

There were presents and alms to hand out in Ippolito’s name. Fiorini organized porters to deliver paschal lambs, weaned by the men at Migliaro, to the houses of three of Duke Ercole’s lawyers who were involved in sorting out various disputes on Ippolito’s estates – one of them also received a large cheese from the larder weighing 24 kilos. There were no Easter gifts for Violante, Ippolito’s mistress – this was a time for duty presents and alms, and Fiorini handed out coins to several ‘poor but respectable’ widows. One of these widows, who had three children, earned a meagre living doing the cleaning at the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Another was the widow of the Governor of Brescello, who had been murdered in 1536, leaving her with three small children and pregnant with her fourth – she must have been grateful for the 70 kilos of wheat she was given by Fiorini. The widow of Arcangelo, Ippolito’s table-decker who had died recently in France, received a small sack of flour, as did the motherless son of Bagnolo, Ippolito’s chief stable boy, who had left his baby behind in the care of his brother-in-law. There was extra cash for the convent of Corpus Domini, and Fiorini gave a pair of shoes to a Sister Cecilia so that ‘she will pray every day to God to safeguard Ippolito and keep him healthy and happy’. On Good Friday he handed out coins worth nearly 2 scudi to people making the annual pilgrimage to Loreto, about 270 kilometes away down the Adriatic coast. Loreto was particularly popular with childless women who were eager to pray at the famous shrine containing the house of Joseph and Mary (miraculously transported from Nazareth in the thirteenth century). Fiorini noted in his usual precise way that these coins had been given ‘so that God will keep the Archbishop of Milan healthy and that the Madonna of Loreto will safeguard him from misfortune in France where he is at present’.

Fiorini’s biggest headache during March and April was Renée of France, who had been allowed to return from exile in the Este villa at Consàndolo – largely thanks to the threats relayed by Ippolito from Francis I. Her relationship with her husband had improved to the extent that she was now seven months pregnant and, with her confinement imminent, she took up residence at the Palazzo San Francesco during April (expectant wives of princes in sixteenth-century Europe were literally confined to guard against accidents, and changelings). There are numerous payments to porters for moving Ippolito’s possessions out of the way, and to smiths who fitted new locks to doors and grilles to windows. Renée was a demanding guest. Fiorini himself had to move his office into a makeshift room over the stables. Tomaso Mosto’s rooms and the wardrobe had to be emptied and prepared for her ladies-in-waiting, with new glass panes installed in many of the windows. Her cooks, who were all French, moved into the attic rooms under the tiles where Ippolito’s footmen had slept. The cooks were not happy with their accommodation – one can hardly blame them – and Fiorini had to get a carpenter to install cloth windows, for which the footmen must have been grateful when they returned. Renée herself moved into Ippolito’s apartments (though not his bedroom, which was about to be redecorated) and kept the fires burning with logs from the wood store, for which Fiorini charged her the market price. Shortly after she arrived Andrea and the painters were ready to start redecorating the ceiling of the Great Hall, something which Renée had agreed to, but once the carpenters began to erect the scaffolding for the painters to work on, she changed her mind – as Fiorini politely noted in his ledger – and the porters had to dismantle the half-made structure and take all the wood back to the store.

With Lent over there was meat on the dining-tables once more. Ippolito’s income from the tax on live animals almost doubled from 72 scudi in March to 131 scudi in April, and Fiorini once again had to work out the veal, beef and fish allowances for the three courtiers and their servants. Work also picked up on the farms. According to the calendar on the cathedral portal, April was the month to put the cattle and sheep out to pasture on the new grass. By the end of the month it was warm enough to shear the sheep at Lagosanto. Bigo authorized the wages of the shearers and started selling the fleeces to various cloth merchants in Ferrara. The weather was also now dry enough to start building work in Ferrara and on the estates. Bigo decided that a new hay barn was needed at Migliaro and he commissioned a carpenter at Baura to prepare forty-eight planks of poplar, which were then sent down the Po by barge together with several large beams, bought from the ducal stores in Ferrara. At Bondeno Palamides started to rebuild one of his hay barns in preparation for the harvest, while in Ferrara Fiorini commissioned a team of roofers to replace the roof tiles that had been damaged by winter storms and frost at Belfiore and the Palazzo San Francesco.

April was a particularly busy time in the stables. The new foals had started to arrive in March, and the covering of the mares that were in season was about to start. Several extra loads of barley were delivered from the granary – some of this was to nourish the weaker foals, but most of it was to strengthen the stallions for their exertions (there was nothing extra for the mares). The covering season lasted until the end of June and meant a lot of extra work for the stable boys. Fiorini recorded extra measures of oil from the palace larder going to the stables so that the lads could keep an eye on the stallions at night. Working with the stallions was dangerous work: one of the lads got kicked in the shin and needed medical attention. At the end of June the stable boys were each given 1½ kilos of salami and salted hams from the larder – more of a tip than a realistic payment for the extra work they had put in.

Pierantonio, Ippolito’s trainer, had returned from France on 10 March in time to oversee the foaling and the covering. He had left Paris on 28 January, the day before the new ambassador had left Ferrara travelling in the opposite direction, and he presumably endured a similarily gruelling winter journey across the Alps (one wonders where their paths crossed). He brought back several horses, including a little bay pony, or jennet (chinea), that Ippolito had found as a present for his 6-year-old niece Anna, Ercole and Renée’s eldest child. Pierantonio moved into his old rooms above the stables, next to Fiorini’s office, and Fiorini added him to the list of courtiers receiving allowances for fish and meat – Pierantonio was not quite as grand as Niccolò Tassone and the other gentlemen, and received beef like their servants rather than veal. One of Ippolito’s reasons for sending his trainer back to Ferrara was to acquire some decent horses. Just before Easter Pierantonio went off to Florence, where he spent 37 scudi on a bay which had belonged to Duke Alessandro de’ Medici – Alessandro had been brutally murdered by one of his cousins in January that year and replaced by another, Duke Cosimo I, who seems to have been selling off Alessandro’s stables. The horse must have been impressive because when Provosto Trotti saw it, he informed Fiorini, who duly noted the conversation, that if Ippolito did not like the animal, he would buy it himself.

May is one of the best months in Italy – the air is warm, with none of the stifling humidity of summer, the cherries are ripe and there are plenty of holidays. Even Fiorini did not work his usual long hours, and he must have been anticipating the season when he arranged for beeswax candles to be sent out to Bondeno to decorate the church for Pentecost (seventeen large) and Corpus Christi (eight large, eighteen medium). The ‘holiday season’ started in Ferrara on 23 April when the citizens celebrated the feast of their patron saint. Fiorini had to work that day – a barge-load of 22,500 logs arrived from Codigoro, and 1,000 of them were bought at the wharves. In addition to these two income entries, he also entered two more items incorrectly under income that day, which had to be crossed out and re-entered under expenditure – a new lock and key for one of the feed chests in the stables, and payment to a porter for carrying chests in the wardrobe. In May, however, he took off an unprecedented seven days, including most of the church holidays: May Day (1 May), an old pagan feast which celebrated the start of spring and which was also the feast of his name saints James and Philip, Ascension (10 May), Pentecost (20 May) and Trinity Sunday (27 May), though he did work on the feast of Corpus Christi (31 May).

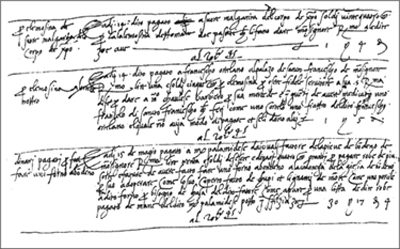

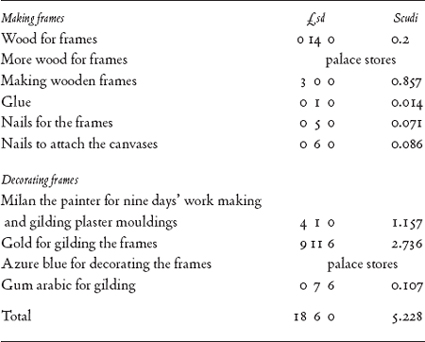

The month brought two unusual interruptions to Fiorini’s routine. On 14 May there was high excitement at the palace when the stepson of Francesco the gardener stabbed a Franciscan friar with a knife. Fiorini offered, on Ippolito’s behalf, to pay the barber who treated the wounded man because, as he entered in the ledger, Francesco was a faithful servant and could not pay the barber’s bill, which amounted to less than ½ scudo. The following day Fiorini unexpectedly bought three paintings from a pair of travelling salesmen from the Romagna. Fiorini had trained as a painter, so we can assume he knew what he was buying, but the purchase was unusual – he did not buy any other works of art for Ippolito – and, although he recorded the transaction in detail, he did not explain who painted them nor why he had bought them. There is no evidence that Ippolito had requested any paintings, and they were not sent to France but remained in the palace in Ferrara. The largest (about 2 × 1 metres) was a Supper at Emmaeus, or, as the more literal-minded Fiorini explained, ‘an oil painting with six large figures, viz a Christ in the garb of a pilgrim with two Apostles after they had arrived in Emmaeus and were at table with three other figures’. The other paintings, both smaller, were a Holy Family – ‘the Virgin and Son and St Joseph’ – and a painting of ‘the battle of Scipio Africanus in oil with plenty of figures and horses’. The total price, 12 scudi, was negotiated by a dealer, who charged a fee. Fiorini then organized the making of frames, which cost almost half the price of the paintings themselves (see overleaf).

Fiorini’s entries for 14–15 May 1537, recording the alms for the convent of Corpus Domini (£1 4s 0d), the sum he paid the barber who treated the Franciscan friar knifed by the stepson of Francesco the gardener (£1 5s 0d), and the money given to Palamides de’ Civali to cover building expenses in Bondeno (£30 17s 4d)

Frames for three paintings

![]()

As Ippolito’s treasurer in Italy, Fiorini was keenly aware that complications had arisen in his master’s pursuit of a cardinal’s hat, though he may not have understood all the political complexities involved. His references to Ippolito’s affairs were succinct – one courier was paid to take a letter ‘which is of importance regarding the trouble the Pope has made’. Fiorini had to pay for couriers to carry urgent letters to Rome and to Milan on several occasions. Couriers were expensive. Fiorini paid 3½ scudi to send a courier to Milan (250 kilometres) and 14 scudi for one to Rome (400 kilometres) – substantially more than he had spent on the three paintings. He was regularly in contact with Antonio Romei, Ippolito’s secretary, who was lobbying on Ippolito’s behalf at the papal court in Rome. In December 1536 Romei had sent Fiorini a bill for 969 scudi for expenses he had incurred on Ippolito’s behalf, and in April another bill arrived on Fiorini’s desk, this time for 81 scudi to cover what Romei loosely termed ‘negotiations’. Fiorini was also in touch with Paulo Albertino, Ippolito’s agent in Milan, where Charles V had ordered the sequestration of the assets of the archbishopric. Niccolò Tassone had spent most of December in Milan, negotiating with the imperial administration on Ippolito’s behalf – Fiorini continued to pay his salary while he was away and gave him 37 scudi to cover his expenses, but his daily food allowances, which were paid at the beginning of each month, had to be deducted from his salary after his return.

Fiorini organized several presents to oil the political machinery in Rome and Milan. Ippolito had sent two horses from France with Pierantonio which were to be sent on to Romei to use in Rome – one of these was a jennet, like the one Ippolito had given Anna d’Este, and the other was a Spanish stallion called il Sarto (the Tailor). Sadly, very little of the correspondence between Ippolito and Romei has survived, so we do not know the names of the recipients, but we can assume they were influential at the papal court. The two horses spent a month in the stables recovering from the long journey and being fattened with extra measures of barley – they were sent down to Rome in April. Fiorini, acting on Romei’s instructions, commissioned elaborate new harnesses and caparisons for the horses. The black leather harness and saddle for the jennet were commissioned, rather unusually, in the English style (al inglese) from a saddler in Ferrara. There were also more prosaic gifts. In June Fiorini sent Romei sixty salamis, a product for which Ferrara was famous. They weighed 52 kilos and, though they were worth little more than 3 scudi, it cost 2 scudi to transport them to Rome (the shipper was not paid until October). Also in June Fiorini sent another twenty salamis together with 6 kilos of candied fruits – citrons, pears and quinces – to Albertino in Milan. Like the salamis, candied fruit was a Ferrarese delicacy, and it had been specially ordered by Albertino to give, as Fiorini noted, ‘to imperial court officials in Milan so that he can have successful audiences with these officials about the business of the archbishopric and so that they will not obstruct things at this time when everything is going so badly because of the Pope’.

Despite the logistics of travel in sixteenth-century Europe, there was a constant flow of traffic between Ferrara and the French court, particularly once the snows had melted in the mountains, making the crossing of the Alps less of an endurance test. During April an envoy arrived from Francis I. He was breaking his journey to Venice in order to visit Renée in the Palazzo San Francesco. He was given Scipio Assassino’s rooms in the palace and was entertained by Tassone, at Ippolito’s expense (the ambassador brought a letter from Ippolito authorizing this expenditure). Tassone hosted three meals for the envoy: they must have been lavish, because the bill he submitted to Fiorini came to over 5 scudi (a year’s wages for a stable boy, or the price of forty-seven geese). He also stayed at the palace on his way back in early June when he again visited Renée – now heavily pregnant – and on this occasion Fiorini presented him with 8 kilos of salamis from Ippolito’s larder.

Inevitably most of the men, whose journeys between France and Ferrara were recorded by Fiorini, belonged to Ippolito’s household. Travellers in either direction meant extra work for him. Departures involved packing crates and dispensing large sums for expenses, while arrivals meant more shopping lists from Ippolito, and names to add to the lists of salaries and food expenses. The first of the spring arrivals was Francesco dalla Viola, Ippolito’s musician, who arrived on 7 May with his servant, and they were duly added to the roster of those receiving veal, beef and fish allowances. A fortnight later Provosto Trotti left Ferrara, riding the horse he coveted from the Medici stables, with 80 scudi to cover his travel expenses to Fontainebleau. He took with him several bolts of black satin from Lucca which Fiorini had bought from a merchant in Ferrara (for 59 scudi) and Ippolito’s suit of battle armour, which had been ordered the previous summer and had finally been completed by Zanpiero, the ducal armourer. Travelling with Trotti was Ippolito’s new Italian barber, Jacomo Casappo, who had been working for Ippolito’s younger brother Francesco, currently travelling in the entourage of Charles V – Jacomo’s new post would give him the unusual experience of service at each of the rival courts. Scipio Assassino, his two servants and Priete the sommelier all returned to Ferrara in June. The party had left Amiens on 10 March, taking over three months to make the journey. We do not know why Priete was travelling, but Assassino, Ippolito’s chief valet and a key member of his household, was unquestionably ill – Fiorini had to pay doctor’s bills for him, and an apothecary’s bill which came to over 2 scudi. Besian the falconer also arrived at about the same time, bringing his birds home for their annual moult. At the end of August Romei arrived from Rome for urgent consultations on Ippolito’s behalf with Duke Ercole. None of these men left Ipplito’s service – the only one to do so was Ippolito Machiavelli, one of Ippolito’s gentlemen, who returned in September and joined his brother running the family bank.

Francesco dalla Viola had brought a shopping list from Ippolito, and on 10 June Fiorini went off to Venice, taking ten days away from his desk to buy these goods, as well as more beeswax candles for the church at Bondeno. He spent a total of 140 scudi, most of which went on quantities of sewing silks that Ippolito wanted – the purple and white silks cost twice as much as the black. He brought the shopping back with him to Ferrara by barge, transferring the goods to a cart for the final part of the journey – the cost was considerable (though it amounted to only 3 per cent of the total).

Scudi |

|

12.5 kg coloured silk thread |

86.80 |

3.33 m red velvet |

17.71 |

5.33 m red satin |

11.81 |

4 m purple cloth |

7.71 |

65 kg white wax candles |

11.34 |

Transport and expenses |

4.74 |

Total |

140.11 |

Shopping in Venice, June 1537

June was another busy month for Fiorini. He took only three days off, one of which was 29 June, the feast of the Apostles Peter and Paul. Renée had her baby on 19 June – her fourth child, a girl they called Eleonora, after her aunt and great-grandmother (her birth coincided with the tragic death of Renée’s niece, Madeleine, the new Queen of Scotland, whose precarious health had broken down on the long sea voyage from France to Edinburgh). A week or so later, most unfortunately, the kitchen well at the palace became blocked. Renée complained and Fiorini called in a plumber to repair it. He also paid her another 2,000 scudi to cover what Ippolito had with-drawn from her agent in France.

![]()

Fiorini was now preoccupied with preparations for the harvest. He bought ink, red sealing wax and new ledgers for the bailiffs on all the estates. The granary sacks had to be washed, dried and mended, and then sent off to Pomposa and Bondeno. There were problems with the mill at Bagnacavallo, and Bigo bought two new millstones from a stone quarry in the north of the duchy, from where Fiorini had to organize bargemen to transport them back to Ferrara and on to the Romagna. Bigo needed materials to repair some of the houses at Fóssoli, and Fiorini organized planks of wood and several sacks of nails from the palace stores. There were also loads of bran and millet to be send out to Bondeno and Pomposa for the tithe-collectors who had started work on 1 June and were supplied with fodder for their horses. A week or so later Bigo had to dismiss the bailiff at Migliaro – we do not know why, but his offence must have been serious for him to be sacked at this critical time of the year. The new bailiff, Domenico da Milano, had been working as a tithe-collector at Bondeno when Ippolito inherited the estate in 1520 and must have proved trustworthy, despite the occasional errors in his tithe books which Palamides recorded in his ledger. One year there were 4 kilos of linseed and 17 kilos of beans missing from what Domenico should have delivered to Palamides, and another year he forgot to take the tithe on six pigs. More serious theft was punished harshly. Palamides had sacked one of Domenico’s colleagues after finding that 70 kilos of chaff and one piglet were missing from his books – produce worth about 1 scudo – and that he had added 2 soldi (0.028 scudi) to the price of some sealing wax he had bought.

Farmland near Bondeno

By 24 June, the feast of St John the Baptist and the traditional start of summer, the grain harvest was well under way. The summer months were extremely busy for everyone employed by Ippolito, in the palace and on the estates. Harvest is the pivot of the year in any agricultural community, the culmination of the previous year’s labours and the basis for future hopes. There was no mechanization to lessen the backbreaking labour of manual work. Ippolito’s workers and their families were out in the fields working in the blazing sun for up to eighteen hours a day, wielding heavy iron-bladed scythes and then threshing the grains and seeds from the harvested plants. There was also work for casual labourers loading the crops into sacks and carrying them down to the wharves. One may not have much sympathy for the iniquitous tithe-collectors, but they too had to work much the same hours as the labourers in order to keep track of the crops as they were harvested. They counted every ear of corn, every pod of peas, every ounce of linseed, and detailed it all in their little notebooks. The bailiffs too were busy, recording the details of every load that arrived at the barns and double-checking their figures with those of the tithe-collectors – missing items, however small, were all recorded. The whole enterprise was supervised by Palamides at Bondeno and by Bigo, who spent the summer making spot checks at Fóssoli and the three centres of the Pomposa estate.

The first crop of the year was hay, which in 1537 was ready in early June. By the middle of the month the barges laden with bales had begun to arrive at the wharves in Ferrara. The first sacks of wheat arrived in early July, the first broad beans and chickpeas by the end of the month. The wheat, which had been harvested at Bondeno, arrived in one of Jacomino Malacoda’s barges on Wednesday, 4 July. Jacomino was back unloading at the wharves again the following Monday, and then either he or his partner did the journey four or five times a week for the next six weeks. This was a particularly busy period for the carters and the porters, and an unpleasant one, doing heavy manual labour in the stifling humidity of Ferrara during the summer. Each barge had to be unloaded and the sacks piled on to carts and taken to the granaries, where the crops were weighed and stacked, and the empty sacks returned to the wharves. However, even in the middle of the harvest, none of the bargemen, porters or carters worked on Sundays, nor on 15 August, the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin, after which the pace began to slacken. Fiorini, on the other hand, needed Sundays and holidays to catch up with his normal routine after a week spent in the granaries recording the details of the incoming harvest.

Grain yields by our standards were very low. Ippolito’s workers got only six grains for every one they sowed, eight if they were lucky with the weather – modern European farmers can expect about fifty – and they needed almost a quarter of their harvest to sow the next year’s crop. Their yields were partly the result of poorer quality grain, but also because of the way it was sown. The seeds were thrown across the surface of the fields and then raked over with a harrow. Some of the grains inevitably remained on the surface where they were eaten by birds or blown away by the wind. (Seed drills, which ensured the seed was buried beneath the surface of the soil, were only developed in Italy in the late sixteenth century.) It was therefore important to waste as little as possible. Even the grass in the garden at the Palazzo San Francesco was cut for hay – three times in the summer of 1537; the first crop, harvested on 4 June, yielding just one-third of a cart of hay. For every seven or eight sacks of wheat brought by Jacomino’s barges, there was also a sack of chaff, which had to be sieved carefully by hand in the granaries. Hidden in the chaff were grains of wheat and barley to add to the granary stores. The chaff also yielded husks, which were fed to the peacocks, chickens and dogs, as well as the seeds of weeds such as ryegrass and oats that were used as animal fodder.

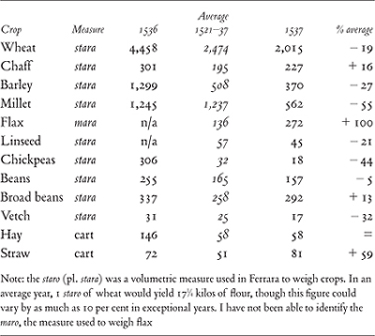

The 1537 harvest was poor – yet another piece of bad news for Ippolito. Then, as now, the quality of the harvest depended ultimately on the weather. The summer of 1537 was spectacularly wet, affecting both the yields and the quality of the crops. Much of the grain was still damp when it arrived in Ferrara, and one particularly large load of wheat from Codigoro was judged by Fiorini to be ‘soaking wet and foul’. At the end of July torrential rain damaged the roof of the granary in Ferrara, flooding the wheat stored there and doing so much damage that some of it was not even fit for chicken feed and had to be thrown away. What a contrast to the year before – in 1536 Fiorini had been obliged to pay Jacomino Malacoda and the other bargees a higher rate than normal because of the severe drought which had left the Po so low that it was impossible to carry a full load on their barges. The 1536 harvest had been exceptionally good but in 1537 the quantities of grain, especially wheat and millet, were way below average, while chaff and straw were well above, another indication of a bad year. The legumes were less badly affected, while the quantity of flax, which thrives in damp conditions, was double that of the previous year.

Harvests at Bondeno, 1536–7

Bad harvests could be disastrous for agricultural workers and their families who depended on their produce to survive the following winter, but they were not always bad news for those like Ippolito who had large estates that produced a surplus of crops to sell. Poor harvests invariably meant higher prices. In November 1536 the price of a stara of wheat had dropped to 19 soldi, but a year later it was 24 soldi and in 1539, after an even worse harvest, it rose to 57 soldi, a price that caused widespread famine.

By September the crops had been harvested, most of the grain and legumes had arrived at the granaries and the wine harvest had begun. The first barges laden with heavy wooden barrels filled with the new wine arrived from both Bondeno and Codigoro on 8 September, the feast of the Birth of the Virgin (described by Fiorini as Santa Maria di Settembre). The day was celebrated in the church at Bondeno by a special service, followed by a harvest supper for Palamides, the tithe-collectors and the priests, though not the workers, at the local inn. With the hard work over for the year, Ippolito’s agents now turned their attention to the upkeep of the estate buildings. At Bondeno, Palamides commissioned roofers to lay new roofs on the church, the bell-tower, the tithe barn and several of the estate dwellings. At Migliaro, Bigo Schalabrino authorized Domenico da Milano to rebuild the houses where Marti Bolgarello and Antonio Maria Trova lived. Building was expensive. Palamides spent 8 scudi on tiles alone while Bigo spent over 13 scudi on labour and materials for Antonio Maria’s house and nearly 18 scudi on Marti’s.

Meanwhile Fiorini was having serious problems with the kitchen well at the Palazzo San Francesco. The first plumber had made some cosmetic improvements but had failed to clear the blockage, and Renée insisted that it be rebuilt. Fiorini had been too busy in July to organize it himself, and Tomaso Morello had taken charge of the project. The work proved to be substandard. In early September part of the new wall collapsed, and the builders had to be called in again. Fiorini also had a lot of work to do in preparation for the departure of a large party who left for France on 23 September. The men included Scipio Assassino, now fully recovered, Priete the sommelier and Besian the falconer. They took with them two more members of staff who were travelling to France for the first time: Carlo del Pavone, the larderer, and Francesco Salineo, who had been appointed as the official in charge of funds for the stables, in place of Jacomo Panizato, who had been promoted to purveyor in France. All were given travelling expenses by Fiorini – 25 scudi for Assassino, 10 scudi each for the others – and they took a lot of luggage with them. Assassino had bought Ippolito a new breviary, expensively covered in black velvet, and, when they stopped off in Mantua, he picked up two swords which Tassone had commissioned there for Ippolito. Besian was returning to France for the hunting season with three new peregrines, as well as new jesses, hoods and lures for all the birds. There were several mules laden with crates of goods for Ippolito, all packed by Fiorini. This time Fiorini had arranged for the crates to be wrapped in cloth, which had been specially waxed, to protect them from the autumn rains. These crates contained all the silk thread and materials Fiorini had bought in Venice in June, as well as several bolts of coloured velvets (84 metres), which Fiorini had ordered from Modena, and taffetas (166 metres), which had been sent from Florence by Duke Ercole’s ambassador. Fiorini’s entry carefully noted the price of each colour of taffeta – black, dark red, dark orange and black – in Florentine lire, and the weights of the bolts in Florentine pounds (the Florentines, confusingly, sold their materials by weight not length). He also packed six new pairs of shoes, made by Ippolito’s cobbler in Ferrara, and three sacks of wheat from the granaries, presumably so that Ippolito could enjoy the Ferrarese delicacies that his cooks had been unable to make with the type of flour produced in France.

![]()

A week after Assassino and the others left was the feast of Michaelmas, 29 September, and the start of autumn. After a wet summer, the autumn was dry, but though the days might have been hot and sunny, the nights were cold. The signs of approaching winter – the colder weather, the shorter, darker days – are all visible in Fiorini’s ledgers. On 1 October, after a break of five months, Fiorini started to dispense tallow candles to the cellars and stables. The next day saw the final cut of grass in the garden at the Palazzo San Francesco. Fiorini started sending millet to Belfiore to fatten the capons and chickens for Christmas. Sales of firewood from the stores began again. Renée bought 4,000 logs during October, while Fiorini himself took a firebrick made of tufa from the palace stores to improve the fireplace in his office in the palace, and had new glass windows installed in his rooms at Belfiore – this was a real luxury, and one wonders whether Ippolito knew of this unexpected extravagance.

October was one of Fiorini’s heaviest months – he took only one day off, a Sunday. He filled in twenty-five pages of expenditure, and three of income, making this easily the longest month in the ledgers. Moreover his assistant, Francesco Guberti, was away for ten days overseeing the loading and shipping of wheat from Ippolito’s estates in the Romagna. Although much of the income in October came from rents, due on Michaelmas (29 September), there were still the last loads of legumes and linseed to record, brought from Bondeno by Jacomino Malacoda, as well as 14,234 bricks and tiles from the kiln at Codigoro and 200 brooms from the workers at Migliaro. In the middle of October Marti Bolgarello, Antonio Maria Trova and the other Migliaro workers came to Ferrara to collect seeds to sow for the next year’s crop. This must have been quite a holiday – a day out in the big city, away from their daily labour in the fields – and Fiorini provided them with bread to eat on the barge on the way back. Marti went home with 50 stara of wheat and 4 of barley, while Antonio Maria took 37 stara of wheat and also 4 of barley (though he had to return the barley a fortnight later because he did not have enough land to sow it).

A lot of the expenditure that month related to the transport of wine – payments to the bargemen, carters and porters, and also wages to the two men who were taken on for the month to work in the wine cellars in the palace, storing and sampling the wines. Jacomino Malacoda and the other bargemen also had to be paid for transporting the grain harvest – we can assume that Jimmie Badtail, a small businessman, was grateful not to have to wait until January for his cash, as he had had to do the year before. In addition Fiorini paid the bargeman who had shipped the two new millstones down to the mill at Bagnacavallo in June. One entry recorded 70 kilos of wheat given to the piano tuner who looked after Ippolito’s musical instruments at the Palazzo San Francesco, while another recorded the cost (1½ scudi) of mending several windows and door latches that had been broken by the staff of Cardinal Benedetto Accolti, who had stayed with Renée for a few days that month. Renée herself left the palace at the end of October. There was also Ippolito’s personal shopping. Fiorini paid 15 scudi to Isaac, a Jewish second-hand goods dealer trading in Ferrara, for a new set of bedhangings embroidered in black and red silk, and there were a lot of bills to settle for the purchase and transport of a new set of Spanish leather wall hangings, which arrived in Ferrara at the end of October.

On 22 October there was an unexpected visitor. Vicino, Ippolito’s trusted squire, had ridden the 720 kilometres from Lyon with an urgent letter from Ippolito to Ercole. In the letter, which was short and, very unusually, written in his own hand, Ippolito asked Ercole to listen carefully to Vicino and to believe what he said, ‘as if it were me myself’. No doubt Vicino brought news of Francis I’s impending trip to Italy – the arrival of the French King in Italy would be provocative to say the least – but the real business concerned Ippolito’s unease at the news from Rome. Alarming rumours had reached the French court from Francis I’s envoys in Rome that Ercole II had ordered his ambassador Francesco Villa to abandon the demand for Ippolito’s hat. It was in order to hear Ercole’s side of the story that Ippolito had sent Vicino to Ferrara. In fact, as the Duke told Vicino, it had been Villa himself who had suggested this radical solution in order to encourage Paul III to accept Ercole’s offer of 170,000 scudi to settle the dispute over Modena and Reggio, an offer which the Pope had rejected. Ercole insisted, both verbally to Vicino and in the letter Vicino took back to Ippolito, that he had no such intention and that he had rejected his ambassador’s advice. But Ippolito knew that Ercole was considering this option very seriously, which put him in a difficult position. He could trust neither his brother nor Villa. Instead he would have to rely solely on Francis I’s goodwill, and the King’s influence with Paul III, to get his hat. With these facts in mind, Ippolito had given letters to Vicino to deliver to Fiorini with orders for a lot of expensive presents for the French court. He also gave Vicino a letter for Romei, instructing him to return to Rome without delay. Romei left a week later, carrying a new silver seal engraved with Ippolito’s coat-of-arms so he could sign documents on Ippolito’s behalf, and 100 scudi from Fiorini to buy perfumed gloves, presents which would be particularly appreciated by their recipients at the papal court.

Vicino also had verbal instructions for Fiorini, of a personal rather than a political nature. Ippolito wanted to give Violante Lampugnana some flax and a cartload – 1,250 kilos – of wheat from his granaries. But the gesture was not quite as generous as it seems. Fiorini’s entry for this transaction explains that Ippolito had specified that the wheat was to be from Baura, and not the Romagna. In October 1537 the Romagna wheat was selling for 24 soldi a staro, while the Baura crop was only making 20 soldi – did she know about this and could she tell the difference between the two? On 27 October Vicino went off to Mirandola, about 50 kilometres away, to collect a horse – a roan – which was a present from Galeotto della Mirandola to Ippolito (Galeotto would one day become the father-in-law of Renea, the daughter of Violante and Ippolito). Vicino tipped both the farrier and the stable boy 1 scudo, spent the night in Mirandola and rode back to Ferrara the next day with the horse. It was soon clear that the horse was ill and needed to be treated with a poultice made from pig fat, mercury, verdigris, mastic and incense – Fiorini did not record what exactly was wrong with the animal. Although it was well enough to leave Ferrara with Vicino, it could not be ridden, and Vicino spent 16 scudi on a new horse to use for the journey back to France. After a very hectic ten days, he left on 31 October, and rejoined Ippolito on the royal progress in Piedmont.

Fiorini took the next day off for the feast of All Saints (1 November). The month started quietly in Ferrara. The fear, widespread across Italy, that Francis I’s arrival in Italy would provoke Charles V to reopen hostilities, proved unfounded, and at last Paul III persuaded the two rival powers to agree to a three-month truce, which was signed on 16 November. Fiorini’s accounts show the arrival of the wheat from the Romagna, wine from Fóssoli and Brescello, and firewood from Codigoro, as well as bales of hay and straw brought by Jacomino Malacoda from Bondeno. The poor harvest meant a lot of extra work in the granaries where the damp wheat needed constant attention. Fiorini described it as ‘hot’ and took on several casual labourers to move the grain around to stop it fermenting. He also had work to do shopping and packing yet another consignment of crates for Ippolito, containing the presents ordered via Vicino. This time there was no convenient party of travellers leaving Ferrara, so Pierantonio took the crates up to Mantua by barge, from where they would be sent to France. This was Pierantonio’s third trip to Mantua that year – he had been there in August to collect four horses which were a present from Duke Federigo Gonzaga to Ippolito, and again the following month to collect two more. The three crates contained the usual bolts of material – this time mostly black velvet – and five of Sister Serafina’s embroidered linen shirts (she had made a total of nine for him that year).

The presents Ippolito had ordered for France were lavish. On his return journey Vicino had stopped off in Mantua to pay a deposit of 40 scudi on three more sets of embroidered sleeves and collars, which were ready to leave with the crates in December. Fiorini packed two new viols, in specially made leather cases, and 9 kilos of candied fruits, over half of which were quinces, divided between six small stone jars. There was a set of four candlesticks, which Fiorini had ordered from one of the ducal goldsmiths – these had been made with 820 silver coins (worth 82 scudi), and the goldsmith was paid another 14 scudi for their manufacture. Some of the silver was used to make the seal which Romei had taken to Rome and for which the goldsmith had been paid less than 1 scudo. The most expensive present – significantly, in view of Ippolito’s situation – was a suit of armour for Montmorency, which was commissioned by Ippolito Machiavelli, now running the family bank in Ferrara. He paid a deposit of 20 scudi to Zanpiero the ducal armourer, on 7 November and must have told him the commission was urgent, because the deposit was double the sum paid for the last suit ordered for Ippolito. Zanpiero worked quickly. By the end of November, just three weeks later, the armour was ready for gilding, and Machiavelli gave him the first of several instalments of gold coins to melt down. The armour was finished by the middle of December and cost Ippolito the substantial sum of 67 scudi (the gilding alone cost 25 scudi). Machiavelli had one last duty to perform for Ippolito that year: on 16 December he attended the christening of Niccolò Tassone’s baby daughter, acting as proxy for Ippolito, who had been made godfather.

Another sign of Ippolito’s misfortunes was the return of Alfonso Cestarello, his old major-domo, to Ferrara in late November. Cestarello had recovered from the illness that had kept him in bed for the best part of six months in 1536. That autumn Ippolito had appointed him to manage the anticipated income from the French benefices to which he had been nominated by Francis I. This proved overly optimistic: all the benefices remained blocked by Paul III in Rome. Ippolito therefore decided that Cestarello would be more usefully employed as his commissario generale, taking charge of his affairs in Ferrara. This must have been a blow for Fiorini. Although his job changed little in content, Cestarello ranked higher than him and was now, in effect, his boss. Cestarello’s first task was to supervise the ducal accountants doing the audit on Ippolito’s books – Fiorini’s ledgers as well as those from the estates. The bailiffs themselves spent two weeks in Ferrara and the bailiff from Fóssoli lodged with Fiorini at Belfiore. The work was all done at Cestarello’s house in Ferrara, and he asked Fiorini to supply ink and paper, as well as 2 kilos of tallow candles and 200 logs for the fire.

A lot of Fiorini’s entries in December relate to the estates. Palamides needed money to pay the roofers working at Bondeno, while Domenico da Milano had to pay the builders working on Marti Bolgarello’s house at Migliaro. One major item was a herd of cattle for the workers at Migliaro, which cost Ippolito 67 scudi. There were twenty-one animals in all, including an ox – a large one, noted Fiorini – and eight dairy cows. Fiorini named all the dairy cows in the ledgers, among them Bride, Little Bride, Gypsy, Rosie, Sparrow and Falcon. A lot of poultry arrived from the estates that month, including over 100 capons which were kept at Belfiore to be fattened on millet for the Christmas market – one of the capons was the annual rent paid by the widow of a carter for a field at Migliaro. The Christmas pigs arrived on 14 December from the workers at Bondeno, Codigoro and Migliaro. They ranged in size from a relatively puny 40 kilos to the magnificent beast bred by Marti Bolgarello, which weighed in at 89 kilos (Antonio Maria Trova’s pig was one of the smallest, weighing only 54 kilos).

The pigs, all fourteen of them, were made into hams and salamis. No doubt anticipating an increased demand for these Ferrarese specialities to oil the political machinery in Rome and Milan, they doubled the quantity they had made the year before. Fiorini bought another fifteen pigs in the market in Ferrara, which cost 45 scudi and weighed an average of 77 kilos each. The pigs were killed by Piero, a gardener who specialized in this bloody task – he made 2 soldi 6 denari per pig, earning over 1 scudo for butchering all twenty-nine. The process of making the salamis was supervised by Madonna Laura, Ippolito’s stepmother, and the work was done by women at Belfiore, in a room which Fiorini had had specially cleaned for the purpose. Fiorini does not explain who these women were, but possibly this was a task which, like sewing sheets, provided extra work for the wives of Ippolito’s staff. The team of women were paid for their thirty-two days’ work in pig meat, earning about 4 soldi a day, half the rate paid to manual labourers working on building sites. Fiorini also had to organize all the equipment and ingredients needed by Madonna Laura and her women. He bought intestines (pig and ox) to case the salamis, and arranged for candles, firewood, spices and salt to be transported from the Palazzo San Francesco stores. The pork needed a lot of salt (416 kilos), but this was not as expensive a commodity as we are often led to believe. Salt in 1537 in Ferrara cost 9 denari a kilo – expensive by today’s standards but not excessively so: 3 kilos of salt was worth about the same as a chicken, and a carpenter earned the equivalent of 15 kilos a day.