6

The Business of Pomp

ONE DAY IN late September 1537, while the French court was making its leisurely progress from Paris to Lyon, Ippolito was spotted by the Florentine goldsmith, Benvenuto Cellini. In his autobiography – a racy and highly subjective account of life in sixteenth-century Europe – Cellini described how he joined the huge crowds of hangers-on who were following Francis I’s entourage, and how he singled out Ippolito as someone worth cultivating as a possible patron. Cellini was ambitious and must have noticed that, although Ippolito had several musicians with him, he had no artists in his retinue (he did in fact employ two, but both had abandoned their jobs as painters for work with better prospects: Fiorini was now in charge of Ippolito’s affairs in Ferrara, and Panizato, who had only been with Ippolito for eighteen months, had already been promoted from an administrative job in the stables to purveyor). Ippolito’s background and prospects made him an obvious target for Cellini. He was an Italian aristocrat and he had excellent connections at the French court. Gossiping with his friends in the crowd, Cellini would certainly have heard that Ippolito was Francis I’s main candidate for a cardinal’s hat, and he knew that success with Ippolito would bring him directly into the royal orbit. But it was not just Ippolito’s rich and privileged background that caught Cellini’s eye that day – it was also his appearance.

Appearances mattered in sixteenth-century Europe. For kings and princes, ostentatious display was essential. In modern terms, Ippolito wore exquisitely cut suits from Savile Row, his watch was a Rolex and he drove a Porsche. Just as we may recognize different designer labels or makes of car, and make judgements about people based on the size of their house or their choice of hobbies, so the people of sixteenth-century Europe had their own ways of assessing appearances. They knew the prices of cheap cloth and fine velvet, could identify a thoroughbred horse from a hack, and could tell the difference between vulgarity and style. For Cellini, as for any other artisan, cook, cleric or courtier in search of a patron, a big spender was a potent magnet. Cellini would have been quick to spot Ippolito’s taste for conspicuous consumption.

Ippolito travelled in style. His pack mules and wagons were instantly identifiable by the coat-of-arms embroidered on the cloths that covered his luggage. His footmen were dressed in his personal livery colours of orange and white. His valets wore outfits of black velvet, clothes which Cellini would have been able to see at a glance were valuable enough to be pawned. His horses were caparisoned in black velvet embroidered with gold thread, with plumes of black and white feathers on their heads that shimmered in the autumn sun, and his dogs wore red leather collars studded with silver.

Then there was Ippolito himself, splendidly dressed in silk, velvet and damask – and fur if the weather was cold. His rings were valuable, as were his rosaries, and his hat glittered with gold ornaments. His swordblades were made of the finest Toledo steel and embellished with elegant gilded hilts specially made for him in Ferrara. He did not just look rich. Once Cellini got close to him, he would have been able to smell the citrus and jasmine oils scenting his beard and the expensive ambergris and musk that perfumed his gloves.

Ippolito’s extravagance was not limited to his clothes, his accessories and his entourage. There were other areas in which a man of his position was expected to show off his wealth. Ippolito needed furnishings to provide an appropriate setting for his sumptuous dinner parties, and expensive silver for his table. Above all, he was expected to be extravagant in what he gave to others – generous with his alms and tips, and lavish with his presents.

We use the adjectives of magnificence – gold, silver, velvet or damask – to conjure up a visual image of wealth, but we rarely have the opportunity to consider how this image was created or what it actually cost. Thanks to Ippolito’s account books, however, we know exactly how much he spent on his clothes and accessories, and on presents, alms and tips. The ledgers might lack the personal touch of a letter but they do allow us to put a precise financial value on the cost of display.

The inventory of Ippolito’s possessions, compiled by Mosto and Fiorini in October 1535, before the move into the Palazzo San Francesco, contains a list of his jewels. He took them all with him to France, and Fiorini made a copy of this part of the inventory so that Mosto could keep track of these valuable items. Like most rich and powerful men of his era, Ippolito wore a lot of jewellery, and much of it was gold. He had two gold chains decorated with black enamel, and several rings, three of which contained precious stones – a diamond, a ruby and a turquoise, all set in gold. He owned six rosaries made of lapis lazuli, agate and garnets. These were not functional aids to prayer or indicators of piety but lavish personal ornaments worn for the display of wealth. In addition, Mosto’s inventory lists a stock of 181 spare rosary beads and over 275 ornaments to decorate the brims of Ippolito’s hats, most of them made of gold and others enamelled in blue, black and white.

Ippolito dressed like a secular prince, not a prelate, in the standard male attire of the non-clerical world. His normal daily dress was a doublet (giuppone) worn over a shirt (camisa), breeches (bragoni) and hose (calze), covered by a thigh-length belted tunic (saglio). His breeches were normally made of velvet, with hose in matching silk, wool or cotton. His shirt was made of fine linen, and its frills, embroidered by Sister Serafina, showed conspicuously at his neck and wrists. The doublet was a light garment, not unlike a waistcoat, and was made of silk, taffeta or satin. Ippolito’s were usually elaborately decorated – covered with tiny ornamental pleats, studded with little silk knots, or threaded with strips of velvet. The saglio – the word ‘tunic’ does not carry quite the right overtones of grandeur – was heavier and longer than the doublet, often made of velvet and usually worn open across the chest to show off the tailor’s work on the doublet beneath. In winter the saglio might be fur-lined. When Ippolito went out he wore a coat, made of damask or velvet, over this ensemble, and in winter he wore a second coat as well, heavier and also lined with fur.

Standard male attire of a linen shirt, with ruffles showing at the neck and wrists, doublet, saglio, breeches and hose, and an expensive fur-lined coat The Business of Pomp

Ippolito owned a great many clothes. It took Mosto and Fiorini four days to compile the list for the 1535 inventory – over 400 items and 611 shoelaces – carefully identifying each garment by colour, material and decoration. By any standards, it was an enormous collection for a 26-year-old, even if he was the son of a duke and Archbishop of Milan. Only forty-three of the items were religious – Ippolito owned eleven archiepiscopal cloaks and capes, five white linen rochets and twenty-seven hats. Sixty-one items were identified as clothes he used for hunting, jousting or dressing up for Carnival or other festivities. Judging by the relative quantities, Ippolito clearly preferred partying to performing his religious duties. His dressing-up clothes included three peasant’s outfits, one pair of sailor’s breeches, thirty hats and two fleeces which, as Fiorini detailed, he wore as wigs. The most splendid items were his jousting saglii. One, in dark red velvet, had a sleeve striped in Ippolito’s personal colours of orange and white, while another was made of cloth-of-gold threaded with red velvet ribbons. The bulk of the items were the clothes Ippolito wore every day. His nightwear consisted solely of a bedcap – he had four, all made of fine white linen and embroidered by Sister Serafina with red or black silk. Like most Italian men of that era, he wore nothing else in bed.

Ippolito’s hats, shoes, boots, breeches and hose were all made by specialist suppliers in Ferrara. He provided a lot of work for Pietro Maria, the hatter. The inventory lists a total of eighty-six hats, excluding the bedcaps and fleece wigs – two were decorated with peacock feathers and two were made of straw. Most of his boots and shoes, including his leather tennis shoes, were made by Dielai the cobbler. Dielai charged about 1 scudo for a pair of leather boots, and roughly the same for five pairs of shoes. Ippolito’s everyday shoes had leather soles and black velvet uppers, made with material supplied from the wardrobe, and he got through an average of eighteen pairs every year. His breeches and hose, again mostly black velvet, were made as a single unit by hosiers, who charged around 8 scudi a pair. The hose often needed replacing – ¾ scudo for woollen hose, over 1 scudo for silk.

Fine linen shirts |

7 |

Doublets |

14 |

Breeches and hose |

11 pairs |

Saglii |

11 |

Coats and overcoats |

46 |

Hats |

29 |

Leather boots |

5 pairs |

Shoes |

54 pairs |

Bedcaps |

4 |

Handerkerchiefs |

102 |

Gloves |

15 pairs |

Inventory of Ippolito’s everyday clothes, 1535

The only items not made in Ferrara were his Spanish leather gloves. They were a new fashion in Italy, where many people, including Paul III, preferred to wear more traditional gloves made from the soft skin of unborn calves. Top-quality Spanish gloves were still not available in Ferrara and Ippolito had to buy his in Mantua. The gloves themselves were relatively cheap – they cost 10 scudi for a dozen pairs. The real expense lay in the ambergris and musk which were used to perfume them. Ambergris, which comes from the intestine of the sperm whale, cost 417 scudi a kilo; musk, the secretion of the musk deer, was marginally cheaper at 278 scudi. Although the amounts of these aromatic substances needed to perfume a pair of gloves were small, they added 35 scudi to the cost of twelve pairs, making a price of 2 scudi per glove.

Gloves

Apart from his shirts, which were embroidered by Sister Serafina, most of Ippolito’s clothes were custom-made by tailors, several of whom worked for the ducal court. One year Assassino had to provide a tailor with candles so that he could work all night to finish a coat that Ippolito wanted to wear for the St George’s Day festivities. The doublets, saglii and coats listed in the 1535 inventory were predominantly black. Black was the ducal fashion for everyday wear in Ferrara – expensive but unostentatious, and the colour worn by courtiers and merchants. It was also the Spanish style, and the look had been popularized in Ferrara by Ippolito’s grandfather, Ercole I, who had spent much of his childhood at the Aragon court of Naples. Over half Ippolito’s doublets were black – he owned four in black taffeta, one finely pleated, another threaded with black velvet ribbons. Twenty-one of his coats were black, including a woollen mourning cloak which must have been made for Ippolito when his father died in October 1534. Most of the other garments were red. This was not as monotonous as it sounds. Ippolito wore many different shades of red – a brilliant scarlet, a rich brownish red, a luxurious dark burgundy and a distinctive purple, which was so dark that it was almost black. He was also fond of a dark leonine orange. One of the few items outside this range of colours was a particularly dapper doublet in blue and yellow shot silk. A lot of the saglii and coats were decorated with stripes, and many of the coats had slashed sleeves in the same colours – two embellishments which were fashionable in Ferrara. Though the colours of these details were the same, there was contrast in the fabrics – black velvet striped with black satin, dark red damask lined with dark red silk, or scarlet satin trimmed with a scarlet silk fringe.

Soon after his arrival in France, Ippolito decided to add a fulltime tailor to his household. Antoine was a Frenchman, though his name is Italianized in the ledgers to Antonio. His importance to Ippolito’s image was evident from his salary. Earning 48 scudi a year, he was paid more than anyone else in the household except the salaried courtiers, and received twice as much as Ippolito’s chief cook, Andrea. Antoine was also paid a pro rata sum for each item he made – this included not only Ippolito’s clothes and furnishings, notably velvet covers for tables and a particularly elaborate set of red satin bed-hangings, but also the cloths embroidered with Ippolito’s coat-of-arms that covered his luggage, and clothes for the household. Antoine had to work hard for his money. His bill in 1540 listed 120 items and came to over 212 scudi, making him the highest-paid member of Ippolito’s household.

Antoine’s first task was a makeover of Ippolito’s wardrobe, changing both the style and the colour of Ippolito’s clothes to suit the fashions of the French court. Unrelieved black was less popular for those of rank at the French court, and so was the Ferrarese preference for stripes or slashed sleeves, which both looked dated and provincial. All seven doublets and eighteen of the twenty saglii that Antoine made in 1540 were coloured. Some were dark orange but most were in one of the various shades of red, lined with the same colour in silk – the preference for colour co-ordination did not change. His coats, however, now had wider sleeves – as the ledger put it, ‘in the French style’ – and his breeches were longer in the leg. The 1535 inventory lists only a few garments in a distinctively national style. Fiorini described one coat as Milanese and another, in black damask, as German – England does not seem to have had a high fashion profile in sixteenth-century Europe, though it was famous for weapons, armour, hunting equipment and a particular style of harness. It is not clear how far the design of garments carried political overtones. The choice of black in Ferrara may have been associated with Spain but it did not indicate a particular political allegiance. The shoes Dielai made for Ippolito were all detailed as either French or Spanish, and the rivalry between Charles V and Francis I did not stop Ippolito from buying both gloves and sword blades made in Spain.

Antoine also made several extra quilted and fur-lined garments for Ippolito, though this had more to do with the freezing winters in northern France than with fashion. He made several fur-lined coats for Ippolito to wear in the privacy of his own chambers – one in orange taffeta lined with lynx, another in red taffeta lined with sable. There was also a very heavy overcoat – called a saltimbarcha – in scarlet woollen cloth with borders of sable and a fox fur lining. In his bill, Antoine specified that it was intended for Ippolito ‘to wear over his other clothes when he rides in extreme cold’.

Ippolito may have worn the same type of garments as other men but the quality of his clothes set him visibly apart from the crowd. The fact that he wore a clean shirt every day, even when travelling, was in itself an indication of wealth. The cost of laundering a shirt was small, but it added up to 8 scudi a year, a luxury few could afford. With daily washing the shirts inevitably wore out quickly – Fiorini sent nine new shirts to France during 1537. The decorative details on Ippolito’s doublets, saglii and coats were conspicuously expensive. Pleating, ribbons, stripes, slashes and trimmings all involved a lot of sewing and added significantly to the cost of making a garment. Antoine charged only 1 scudo for a plain doublet but 5 scudi for one with fine pleating across the front. Slashed sleeves, which involved long cuts in the velvet or damask garment and the insertion of material or fur, carried the unmistakable message that the owner was rich enough to waste valuable material. Quilting a garment by hand was a long process and particularly expensive. Antoine charged 1 to 2 scudi for a plain saglio but over 14 scudi for a quilted one, and as much as 30 scudi for quilting a coat. Fur was also expensive, and Ippolito wore a lot of it. A fox pelt cost 1½ scudi, a sable 12 scudi and a lynx 13 scudi. The furrier’s bill for lining one saglio with lynx came to 23 scudi. Not surprisingly the sable and lynx were usually reserved for the exterior of the garment, while cheaper fox fur (and sheepskin) did the practical work inside, keeping Ippolito warm – you needed eight fox pelts to line a saglio, but only two sables to trim the edges.

A saglio with quilted sleeves

![]()

Cellini and other onlookers in the crowd would have noticed all these things but above all they would have spotted the quality of the material used for the garments themselves. Expensive textiles were our equivalent of designer labels, and the materials favoured by Ippolito – velvet, silk, taffeta, satin and damask – were all staggeringly expensive. Tomaso Mosto hoarded every scrap of material in the wardrobe, and his ledger detailed each occasion when Antoine dismantled a garment that Ippolito no longer used, listing the precise length of the pieces that went back into the wardrobe to be recycled as trimmings. The saltimbarcha which Antoine made for cold weather was trimmed with red velvet from one of Ippolito’s old saglii. The manufacture of textiles in sixteenth-century Europe was labour-intensive – there were no electric machines or synthetic fibres to simplify production and lower costs. The entire process, from spinning and dyeing the thread to weaving and finishing the cloth, was done by hand. One metre of black velvet could cost as much as 2 scudi, the equivalent of twelve day’s wages for a master-builder, and the price of twenty-three plump capons or 1,275 logs for the fire. It took three metres of material to make a doublet (6 scudi), nine for a saglio (18 scudi) and over eighteen for a long coat (36 scudi) – and then there was the price of similar lengths of silk to line these garments.

Other factors also influenced the price of textiles. Provenance was important. The best – and the most expensive – velvet and damask came from Venice, while the finest taffetas were made in Florence. Moirés, damasks and other figured fabrics with complicated patterns that were woven in at the loom were more expensive than plain textiles. Colour was another significant factor. Given the importance of appearance, and Ippolito’s unerring eye for quality, it should not come as a surprise to find that the black and red which dominated his wardrobe were markedly more expensive than other colours. Orange textiles were as much as 25 per cent cheaper than the same material in black. Black was a hard colour to dye properly, which made it expensive. However, it was not as expensive as the various shades of red which were all dyed with kermes (cremesino, from the Arabic, qirmiz), a dye made from insect bodies and imported to Venice at considerable cost from the Middle East. The darker the red, the more it cost – a metre of dark red velvet cost about 3¼ scudi, but the same length of dark purple velvet could come to as much as 4½ scudi. These materials were even more expensive in France, where merchants had to pay transport costs and taxes to import Italian fabrics. The length of dark red kermes-dyed damask needed to make a long coat cost 43 scudi in Venice but 59 scudi in Paris. This was why Fiorini sent so much material to Ippolito in France in 1537 – 653 metres of velvet, damask, satin and taffeta, worth a total of 968 scudi.

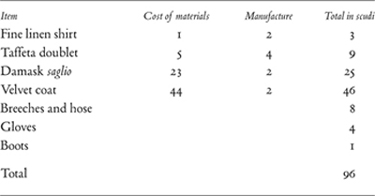

Although it is impossible to know exactly what Ippolito was wearing that autumn day when Cellini spotted him on the road to Lyon, it is possible to estimate the value of a typical outfit from the account books. The table opposite is based on Antoine’s ledger – one of Sister Serafina’s shirts, a pleated doublet made of red Florentine taffeta, a dark red damask saglio trimmed with velvet from one of Ippolito’s old garments, a black velvet coat lined with black taffeta, as well as his usual breeches, hose, gloves and boots. I have assumed that the weather was warm that September, and that neither his coat nor his saglio had fur linings, which would have added another 30 scudi to the bill. Even so, the cost of this hypothetical outfit comes to 96 scudi – a sum that would take a carpenter or a builder nearly three years to earn. No wonder Cellini was impressed.

It was not just Ippolito’s clothes that provided clues to his rank. There was also his household. The number of those who travelled with him grew steadily during his years in France. In 1536 he had fifty-two men with him, a quarter of whom returned to Ferrara, but by 1539 his entourage in France numbered over sixty. The largest increases were amongst the staff responsible for food and music, a sign of the importance Ippolito attached to entertaining in style. In 1536 Ippolito had only needed two credenzieri – he now had three, and three assistants. He added a second sommelier and, in the kitchens, where two cooks and a boy had once sufficed, he now had six cooks and three boys to prepare and cook his elaborate dinner parties. Moreover, many of the new men on whom he depended to create an impressive image were French. In addition to Antoine, his French tailor, Ippolito employed two French credenzieri and two French cooks, one of whom was a pastry cook from Blois. Most significantly, he took on six new musicians – a bass, two tenors and three boy sopranos, all of whom were French or Flemish.

The cost of an outfit

The visual appearance of the men in Ippolito’s entourage had a direct impact on Ippolito’s image, and Antoine the tailor made clothes for several members of the household as part of their wages. The falconers and kennelmen were dressed functionally in black fustian jackets, white cotton shirts, red stockings and shoes or boots. Although the jackets cost less than 1 scudo, their shoes and boots were well-made and only marginally cheaper than those Dielai supplied for Ippolito himself. They were certainly better-quality clothes than they could afford themselves. The valets, footmen and pages – Ippolito’s formal retinue – were more expensively dressed in clothes deliberately designed to impress. Assassino and the other valets dressed in black, wearing saglii and doublets of black velvet over white shirts, black breeches and black stockings. For formal occasions they changed into orange satin doublets and wore black hats. The white cotton Antoine used for their shirts was of better quality than that used for the kennelmen and falconers, but a lot cheaper than the fine linen of Ippolito’s shirts. The doublets were plain, with none of the pleating or other elaborations which Antoine sewed for Ippolito. The velvet was also cheaper, though sometimes the doublets were made from material salvaged from Ippolito’s old garments – Antoine took apart one of Ippolito’s black velvet coats to make a new saglio for one of the valets. The footmen on duty wore doublets striped in Ippolito’s colours of orange and white, dark orange breeches, grey stockings, which were patterned with orange and white, and red hats. The pages were even more brightly coloured, in orange doublets and red stockings. All were provided with leather shoes and boots, and travelling cloaks – black cloth for the valets, grey cloth slashed with grey velvet for the footmen and pages. These cloaks were not cheap. One careless page left his behind somewhere between Lyon and Paris, and Antoine spent 8 scudi on the materials he needed to make a replacement.

Above all, it was the size of one’s household that was the indicator of rank, and for the most prosaic of reasons – a large household was very expensive to maintain. Ippolito had to pay not only his entourage in France but also the staff running his estates and residences in Ferrara. His annual salary bill came to around 2,400 scudi, but this was only part of the story. Ippolito also had to feed his men, and provide accommodation. The cost of feeding himself and his household in Lyon in 1536 worked out at 5½ scudi a month for each member of the household, or 3,960 scudi for sixty men over a year. On top of this there were the food allowances he paid to the servants of his courtiers, the stable boys and the men who remained behind in Ferrara, which added another 350 scudi to the bill. He also had to pay for stabling and fodder for his horses in France. It is difficult to estimate this figure precisely. We know that he saved money by providing his own fodder whenever possible. Innkeepers charged the equivalent of 40 to 50 scudi a year for stabling and feeding one horse, and the cost of stabling was only a fraction (2 scudi) of the whole. Assuming he could save 50 per cent on the price of fodder, then the cost of looking after each horse amounted to about 25 scudi a year – and he had at least sixty horses. Then there were the mules that carried his baggage – in 1540 he hired a muleteer and a string of mules for this purpose, and the bill for six months came to 519 scudi. There was also the cost of clothes for his entourage and incidental expenses for the household. The pages and the boy sopranos had their heads deloused every fortnight or so, and their linen, which included a lot of handkerchiefs, was washed at Ippolito’s expense. There were also occasional items, such as the rent of sheets or the purchase of medicines for those who were ill. The total, estimated according to these figures, came to 9,600 scudi a year and accounted for the bulk of his income, which in 1537 was 10,479 scudi. Ippolito was living beyond his means.

|

Scudi |

Salaries |

2,400 |

Food and accommodation |

4,310 |

Horses |

1,500 |

Mules |

1,000 |

Clothes |

370 |

Incidental expenses |

20 |

Total |

9,600 |

Estimated annual cost of Ippolito’s household

The most effective way of displaying status in sixteenth-century Europe was to build a magnificent palace. Given his nomadic existence in France, and the uncertainty as to how long he would remain there, this was not an option for Ippolito (it was not until the mid-1540s that he built an elegant little residence at Fontainebleau, complete with tennis court). Ippolito was allocated apartments by the King’s foragers, who acted on instructions from Montmorency, and their proximity to the King’s chambers was a mark of royal favour. In his enquiries about his future patron’s prospects, Cellini might well have heard that Ippolito had spent the summer of 1537 at Fontainebleau, lodged in the suite of rooms usually given to the Dauphin, who was away fighting.

Ippolito may have had little say in the location of his rooms, but he could – and did – ensure that they were magnificently furnished. The walls of his rooms were hung with tapestries brought from Ferrara – Ippolito regularly tipped the King’s tapestry men for hanging them. He also owned a set of Spanish leather hangings, stamped with gilded decoration, which were more robust than tapestry, though a lot heavier for the baggage mules. This was another new fashion from Spain and presumably very popular in France, because Ippolito ordered the hangings in May 1536, just six weeks after his arrival at the French court. We do not know how many there were, but they were probably intended to decorate more than one room. They cost 350 scudi, plus another 87 scudi to cover transport and currency exchanges. The hangings were made in Valencia and the commission was handled by a Genoese merchant, Ansaldo Grimaldi, who had trading connections in Spain. The Machiavelli bank in Ferrara paid Grimaldi’s bill for the hangings and for their transport from Valencia to Genoa, charging Ippolito 2½ per cent for this service, and Fiorini settled the bill with the carrier who brought the hangings over from Genoa separately.

Ippolito loved expensive fripperies and baubles. He kept the ambergris and musk for his gloves in special silver boxes. He had another little silver box with its own silver padlock, two gilded clocks, one of which sounded the hours, a silver sandbox for blotting letters, three silver dog collars, a set of balances with little silver weights, and twelve pieces of coral. He spent 4 scudi on a silver piccolo for his flautist and 6 scudi on a more exotic purchase, a parrot. Favoured guests might be shown his collection of medals, many of which were antique, and a reliquary – though Mosto did not record what relic it contained.

|

Scudi |

Hangings |

350 |

Transport Valencia–Genoa |

58 |

Transport Genoa–Ferrara |

19 |

Bank charges |

10 |

Total |

437 |

Spanish leather wall hangings

Ippolito also travelled with a large collection of valuable plate in his luggage – gold cups, silver vases, basins and jugs for his dining-table, and silver plates, dishes and spoons for the credenza. Cellini knew that his luxury craft would appeal to Ippolito’s tastes. The goldsmith managed to engineer a meeting with Ippolito on the journey to Lyon and persuaded him to commission a silver jug and basin, which he promised would be ornamented with all’antica decoration. Ippolito intended to give these items to Francis I, and he paid Cellini an advance for the work. However, Cellini, who was a slippery customer at the best of times, did not use the money as Ippolito had intended. In his biography he claimed he was sick of France and used the cash to return to Rome, where he had other commissions waiting for him. Unfortunately Paul III had him arrested and imprisoned in Castel Sant’Angelo on a charge of stealing papal jewels during the pontificate of Clement VII. Ippolito had to wait several years for his silverware, and so did Francis I.

![]()

The act of giving was one of the most public statements of wealth and power. It is difficult to overestimate the importance of presents, tips and alms in sixteenth-century Europe. Ippolito lost few opportunities to distribute largesse to those beneath him in the social hierarchy or to give extravagant presents to those he needed to impress. His reasons were varied – he gave to buy goodwill or political advantage, to gain merit in the eyes of God or simply to reward good work. Gifts were a valuable and indispensable tool in the political arena: Ippolito and his contemporaries made no distinction between bribes and personal presents. Both were gifts and, depending on the status of the recipient, both were bribes, of a sort – and all required a reciprocal gesture.

The account books that survive from 1536 to 1540 record that Ippolito gave over a thousand items – coins and goods – as presents, alms or tips. His bookkeepers divided his gifts into two distinct categories – alms (elemosine) and presents (donatione, which included both presents and tips). The money distributed under the alms account included not only that given to the poor and the needy, but also gifts to religious institutions, such as the coins offered during mass or given to the priest who heard Ippolito’s confession, as well as the sums donated to the building funds of various churches. Almsgiving in this broad sense was a condition of salvation in the Catholic Church and an obligatory act for all good Christians (it was also one of the teachings of the Catholic Church that was rejected by Protestants). Many of the alms were explicitly reciprocal, and Fiorini’s ledgers reveal just how personalized the act of almsgiving could be.

When he departed for France in 1536, Ippolito left behind an army of people in Ferrara praying – quite literally – for his success. One man was paid 6 soldi a month (just over 1 scudo a year) to recite daily prayers to God to ‘protect Ippolito from the plague and any other illness, and to keep him healthy’. The friars of San Francesco, the church closest to his palace, were given azure and vermilion pigments from the wardrobe so that they could paint the organ in their church in return for prayers for Ippolito’s good health. The nun who looked after the tomb of Ippolito’s ancestor, Beatrice d’Este, in Sant’Antonio received regular presents of oil and wax for the tomb in the hope that both God and Beatrice would guard Ippolito from misfortune. Her maid, another poor but respectable widow, was also paid to pray to God on Ippolito’s behalf. Another nun was given a new pair of shoes – Fiorini specified that they were nun’s sandals – because ‘she prays to the Virgin every day to guard Ippolito from disgrace and to keep him healthy and happy’. During the war in Provence in the summer of 1536 the priests of one church in Ferrara held a special mass to pray for peace, and Fiorini gave them 2 scudi to have prayers said ‘to God and the Virgin so that they will guard Ippolito from misfortune’, adding, almost as an afterthought, that the priests should also pray ‘to bring peace to Christendom’. Even Sister Serafina, who embroidered Ippolito’s linen, did her duty. She was given a sack of chicken feed, ‘firstly because she prays for Ippolito and secondly because she sews his shirts’ (the convent also received money for each shirt she embroidered).

Whether it was deliberate or accidental, a high proportion of the recipients of Ippolito’s alms were women. It was mostly nunneries that benefited from gifts of money or beans, chickpeas and wheat from Ippolito’s estates. Many of the gifts took the form of charitable aid to assist poor girls entering a convent. Fiorini gave clothes worth 1½ scudi to a Jewish girl who had converted to Christianity and wanted to enter Santa Caterina di Siena. There were new blue bedcovers, worth 3 scudi, for two girls who entered the convents of San Gabriele and Corpus Domini and who had offered to pray ‘continuously’ for Ippolito. Entering a convent, like marriage, required a dowry. When his old valet died in 1535, Ippolito was generous with clothes for his four children and financed one daughter to join Santa Caterina Martire. To celebrate her final vows, which she took in June 1536, he paid for a party for her at the convent. This was quite a feast: Fiorini sent cheese, raisins, flour, sugar and almonds from Ippolito’s larder, and wine from the cellars, as well as one whole calf, eggs, more cheese, fish, oranges and lemons, all specially bought for the occasion.

Fiorini’s ledgers make it clear that alms handed out were given in the expectation that God would reward Ippolito. Equally,

the recipients of presents were expected to honour their side of the bargain. Despite the quantity of people praying for him

in Ferrara, Ippolito placed far more trust, in financial terms at least, in the tangible relationships of the real and overwhelmingly secular world. Put in this context, it has to be said that Ippolito

was not particularly generous with his alms. His income in 1537 came to 10,480 scudi. We do not know how much he handed out

in France that year, but Fiorini distributed coins and goods worth a total of just 26 scudi to the poor in Ferrara, and another

22 scudi to monasteries and convents in the city (40 per cent of this to the convent of Corpus Domini, where his sister was

Abbess). The total, 48 scudi, would only have paid for enough velvet to make two of Ippolito’s saglii. The contrast between Christian charity and secular presents was striking. When his aunt, Violante d’Este, died in March

1540, Ippolito had prayers said for her in each of the seven major churches in Rome, a gesture that cost him ![]() scudo. That

was only marginally more than the tip of ½ scudo he gave to the owner of a dog that covered one of his bitches, and a tiny

sum in comparison to the 5 scudi with which he tipped Paul III’s buffoon.

scudo. That

was only marginally more than the tip of ½ scudo he gave to the owner of a dog that covered one of his bitches, and a tiny

sum in comparison to the 5 scudi with which he tipped Paul III’s buffoon.

Tipping was expected for services rendered without charge – and that included entertainment. Fiorini recorded several tips to peasants who returned lost falcons, and one of 10 soldi (just over a tenth of a scudo) to a gardener who returned some of Ippolito’s peacock chicks that had escaped from the garden at Belfiore – as Fiorini explained in his ledger, the man could have sold them, and no one would have known. Tips were the chief means of negotiating status down the social scale and were often associated with travel and the public display of prestige. Ippolito’s standard tip on the road was 1 scudo – this single gold coin had value across Europe and, at a practical level, it was easy accessible in his money bags. It also represented a very substantial sum for many of its recipients – it represented a fortnight’s wages for a labourer and would buy twenty-eight chickens, ten geese or 50 kilos of flour.

Ippolito’s footman handed out these coins to gate-keepers, guides, couriers and ferrymen and, occasionally, to innkeepers. For the ferrymen who transported Ippolito and his household across the rivers of Europe, this was not the price of the journey, in the sense of a ticket. There seems to have been no charge per se and the system worked well for the simple reason – unimaginable today – that the obligation on the rich to show off their wealth was more effective than any legislation. Staying the night in a private palace involved a lot of 1-scudo tips. It was customary to tip all the musicians who had played at the banquet as well as the cooks, the credenzieri, the wine waiters and other dining staff, and the officials in charge of the stables, the cellars and the wood stores. Ippolito also tipped the bearer of presents to himself, invariably a member of the donor’s household. For all these men, 1 scudo represented a substantial proportion of their wages – and Ippolito’s own staff must have benefited in the same way when they distributed presents on Ippolito’s behalf.

Ippolito also regularly tipped entertainers who amused him on the road – itinerant players and singers, dwarves and even young girls acting as May Queens. Several of the entries suggest musicians with physical deformities received tips, but these were a reward for delighting Ippolito, not alms for their misfortune. Once again, the tips reveal a fondness for the female sex. The women in Lyon who regularly rowed Ippolito across the Saône or took him for a ride on the river were a particular favourite and received coins for amusing him – they may have sung for him, but it is more likely that he simply enjoyed their flirtatious banter. One unnamed woman, enigmatically, ‘accommodated Ippolito in her house for half a day while he was out hunting with the King’. Exactly how she accommodated him was not specified, but she received ¼ scudo – not a large sum, but still worth seven chickens.

Money, in the context of gift-giving, usually moved down the social scale, but goods could move in both directions. Ippolito gave a vast range of goods as presents, to an equally vast range of recipients. Some were thank-you presents, such as the stockings for the Venetian stone-cutters who installed the Istrian stone door frames in the Palazzo San Francesco, or the capons he gave his lawyers for Christmas. Others were of a more personal nature. He gave a set of playing cards to his cousin Guidobaldo della Rovere, the Duke of Urbino, and gilded enamel inkwells to his sister Eleonora, Ippolito Machiavelli and the hard-working Fiorini – the quality of the present did not always reflect the rank of the recipient. Violante, the mother of his baby daughter, appears only rarely in the account books. At Christmas 1536 she received a barrel of malmsey wine, Ippolito’s favourite, and four capons. She may also have been the intended recipient of two valuable rings that Machiavelli took from France to Ferrara in August 1537 and of the eight jars of aromatic carnation petals, made by the nuns of Sant’Antonio and given by Fiorini to an unnamed person, or as he put it, a persona segreta.

The largest group of recipients of personal presents were members of Ippolito’s household, who benefited in all sorts of ways from his generosity, over and above their salaries, in return for their loyalty, both past and future. One year he gave Pierantonio the trainer a new set of leather boots, and all his kitchen staff received new jackets, made by Antoine – the cooks’ jackets were black fustian, the boys’ grey cloth. Favoured members of staff were given his cast-off clothes. Andrea the cook received an expensive dark red satin doublet, lined with matching taffeta, from the wardrobe, while Assassino was given one of Ippolito’s old black satin coats, from which the sable lining seems to have been removed, and a sword with an elaborate gilded hilt.

Above all, presents had a political context, like the jars of candied fruits Fiorini sent to Ippolito’s agent in Milan to bribe imperial officials who were causing problems in the archbishopric. Not surprisingly, the main focus of Ippolito’s political gifts was the French court. Success in France was vital to Ippolito, and he worked hard to establish his position at the French court from the day he arrived. His reputation for magnificent banquets was reported in diplomatic correspondence, not just to Ercole II, but also to other rulers in Europe. Part of his success was undoubtedly due to his deliberate, and ostentatious, use of conspicuously expensive presents – suits of armour, swords, gold rosaries with aromatic beads filled with musk and ambergris, perfumed gloves and embroidered sleeves, as well as embroidered linen handkerchiefs, shirts and bedcaps. He even gave away his own horses, medals and other treasured possessions. These presents were far more lavish than those he gave to people back home in Ferrara. They needed to be. Ippolito expected great favours in return, not least his cardinal’s hat.

An elegant late sixteenth-century Italian sword hilt ornamented with all’antica decoration

The importance of good relations with the French court had become all the more imperative since October 1537, when Ippolito first heard the rumours from Rome that Ercole II had decided to abandon the pursuit of his cardinal’s hat. His hopes and ambitions now rested largely with Francis I, and with his principal minister, Montmorency. With this in mind he ordered expensive presents for members of the court, including a particularly splendid suit of armour for Montmorency. He also encouraged his brother to help and asked him to send Montmorency one of his prized Ferrara-bred horses. Ippolito must have been disappointed – and a little suspicious – when Ercole replied that he could not find one good enough. Ippolito responded, diplomatically, that this was a pity, and added, ‘it would be a good idea to try and please him because he is so important’. Just how important soon became clear. On 10 February 1538 Montmorency was appointed Constable of France, the highest honour that Francis I could bestow on him. Ippolito knew Montmorency’s support was essential if he were to realize his own ambitions, a fact that was brought home very forcibly a month or so later when Montmorency used his influence with the King to remove one of Francis I’s oldest friends from court. Ippolito wrote, in code, to his brother with the news:

Although Admiral Chabot is still Governor in Burgundy, the Duke of Guise was sent there the day before yesterday with letters patent appointing him Lieutenant in the same place, with the authority to appoint and sack as he likes … it looks like Chabot’s career is over and it makes one realize how necessary it is to keep in with people at court because two days ago it was possible to say that he was at the top of the wheel and now, with this disgrace, his career has plunged down to its lowest point.

Ippolito must have been worried that his own career might do the same.