|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Almond ![]()

(Prunus dulcis)

Use: Nuts

Aroma/flavor: Honey, nutty

Domesticated almond trees produce drupes, a fleshy fruit with thin skin and a central stone containing the seed as opposed to a nut, that have delicate, sometimes sweet, nutty flavors. They contribute more to beer if they are roasted first. That process removes some oil that, in theory, might inhibit head retention. Bitter almonds (from P. dulcis var amara trees) can be deadly because they contain amygdalin, the compound that can produce cyanide poisoning. The trees are more common in Europe, but also grow wild in the United States.

Smoked character: Nutty, sweet

(Malus domestica)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Fruit, apple

There are more than 7,500 cultivars of the tree, but that doesn’t fully express the diversity of the fruit it produces. A group of scientists sequenced the genome of Golden Delicious to find 57,000 genes, more than any plant genome studied and considerably more than the 30,000 in humans. For the most part, brewers have not tapped into that potential, leaving apples to cidermakers. When brewing, it is easiest to juice the fruit and add it during fermentation. Apple blossoms smell much like the fruit, so can be picked and added late in the boil to provide subtle aroma, at the cost of a potential apple. Apple seeds contain small amounts of amygdalin, the compound that can produce cyanide poisoning. Ingesting small amounts of apple seeds will likely cause no ill effects.

Sugar content: 11%

Smoked character: Mellow, fruity

Apricot ![]()

(Prunus armeniaca)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Apricot, peach

Texture plays an important part in fresh apricots, making the timing of harvest—between May and June—particularly important. Picked too early they are hard and green-tasting; too late and they bruise easily. That’s one reason breeders developed crosses with plums, producing fruit that does not bruise as easily and is juicier. Thus aprium is 75 percent apricot and 25 percent plum, pluot is 75 percent plum and 25 percent apricot, and plumcot is 50 percent of each. Apricot pits also contain amygdalin, the sugar and cyanide compound that can produce cyanide poisoning.

Sugar content: 9%

Smoked character: Milder, sweeter than apple

(Betula)

Use: Sap, branches, bark

Aroma/flavor: Sweet, sometimes “green”

There are five native American and two European birch species that have become naturalized. They are popular with foragers, who make tea from the twigs, tea and spices from the inner bark, and syrup from the sap. As well as replacing water in a recipe with birch sap, which is only lightly sweet, Scratch Brewing has used almost every part of the tree in a beer (see page 290).

Smoked character: Sweet, subtle

Blueberry ![]()

(Cyanococcus)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Blueberry

Anybody who has snacked on blueberries while barely breaking stride during a hike in Acadia National Park understands the link between the fruit and the coast of Maine. The low bush variety is called “wild” and has smaller, more intense berries than the cultivated (highbush) plants. Maine produces 25 percent of all blueberries in North America, although they grow in much of the country. Wild blueberry is the official fruit of Maine and has an intensely local flavor.

Sugar content: 10%

California Bay/Oregon Myrtle/Spicebush ![]()

(Umbellularia californica)

Use: Leaves, fruit, nuts

Aroma/flavor: Spice, pine, chocolate

The large hardwood tree, also called California bay laurel, has pungent leaves that have a similar flavor to the leaves from bay laurel, the native Mediterranean evergreen. Although they may be used as a substitute, that is not true of all laurels. For instance, cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus) is extremely poisonous. Native Americans made a tea from the California bay leaves, using it to cure a range of ailments from headaches to rheumatism. The fleshy outside of the kernel of fruit is edible, while the hard pit is traditionally roasted, and the shelled bay nuts are eaten whole or ground into a powder to be prepared as a drink that resembles unsweetened chocolate. The tree is also known as pepperwood, cinnamon bush, peppernut tree, and headache tree. It is related to, but different than, the spicebush found east of the Rocky Mountains.

Cedar ![]()

(Cedrus)

Use: Needle-like leaves

Aroma/flavor: Musk, earthy, cedar

When Brian Hunt at Moonlight Brewing makes beers with parts of a tree—he’s used many varieties, including incense-cedar—he thinks in terms of the role astringency plays rather than bitterness. “It’s an irritant, a foil for sweetness. That’s what gives you the desire to have another beer,” he said. He’s also interested in maximizing the aroma, so adds branches about 20 minutes before the boil is to end. “I wait until I smell them boil off into steam. They have been extracted into the liquid; now I am starting to lose it. Turn off the boil,” he said. His decision is not controlled by a clock. “There are many factors. What is the boil like? The difference is everything,” he said.

Cherry (and Wild Cherry) ![]()

(Prunus)

Use: Fruit, stems, blossoms

Aroma/flavor: Cherry, almond

More than 99 percent of the fruit grown is sour cherries. The flavor of the fruit is well known and used in a wide variety of beers, while the wood is popular for smoking meat (or grain). The surprise is that the stems of the cherries taste of cherry on their own. Unfortunately, the tree produces chemicals that metabolize into cyanide. With cherries, the chemical occurs throughout the plant and is most concentrated in wilted or fallen leaves.

Sugar content: 10%

Smoked character: Sweet, fruity, mild, and can turn grains pink to rosy

(Castanea dentata)

Use: Nuts

Aroma/flavor: Mildly nutty

Before the early 1900s one in every four hardwood trees in North America’s eastern forests was an American chestnut (C. dentata). In the 50 years after chestnut blight was first identified in 1904, it wiped out almost four billion chestnut trees. Now agricultural researchers in several parts of the country are working to bring it back. In 2014 American farmers harvested just 1.5 million pounds, compared to 200 million pounds worldwide. The chestnut has been called the “un-nut” because it is more like a grain than other nuts, its carbohydrate content comparable to wheat and rice. Urban Chestnut Brewing in St. Louis uses the flour in its Winged Nut beer. Brewmaster Florian Kuplent notes its starch content is nearly identical to Munich malt and the contribution to gravity about the same.

Smoked character: Sweet, nutty

Chokecherry ![]()

(Prunus virginiana)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Cherry, almond

The fruit of this small tree, which grows in most parts of America, was once the most important fruit in the diets of Native Americans in the Northern Rockies and North Plains. It was so central to the economy of both the Blackfoot and Cheyenne that it was simply called “berry” in their respective languages. It is commonly used to make jelly, jam, syrup, and wine. The fruit itself is safe, but chokecherry seeds, leaves, twigs, and bark all contain amygdalin.

Sugar content: 14%

(Cinnamomum zeylanicum)

Use: Stem, bark, inner bark

Aroma/flavor: Cinnamon, spice

Much of what is sold as cinnamon in the United States is imported and actually made from cassia bark. Chinese cassia is a close relative of Ceylon cinnamon, or “true cinnamon.” Both the stem and the bark of either are aromatic, but the spice is made from the inner bark. True cinnamon is more aromatic than cassia. Research conducted by Boston Beer Company found that cinnamon contributes noticeably to perceived bitterness in beer.

Fragrance essentials: Base notes; contains linalool, pinene

Crabapple ![]()

(Malus)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Tart apple

The only apples native to North America, the fruits of this tree were once called “common apples.” They are rather tart, so more suitable for making jellies and preserves than eating. Above-average acidity adds complexity to a beer. The trees are widely grown as landscape trees, popular for their fragrant foliage. The aroma of flowers differs with varieties, with some very pleasant (the flowers may be added post-boil for a floral note) and others equally unpleasant. They have the same toxicity risk as other apples.

Sugar content: 14%

Smoked character: Similar to apple, but generates more smoke

Date Palm ![]()

(Phoenix dactylifera)

Use: Fruit, sap

Aroma/flavor: Dark fruit

Dates are sugar-rich and will quickly boost the alcohol level of a beer along with rich, dark fruit flavor, but add little aroma or acidity. Date wine is produced from the sugary sap of the tree. The sap may also be cooked into jaggery sugar, itself used to add unique flavor to beer.

Sugar content: 60%

(Sambucus nigra)

Use: Flowers, berries

Aroma/flavor: Fruit, honey

Elderberries have long been used to make fruity elderberry wine, while the honey-scented flowers recently became a darling with distillers. The flowers were also used to make wine in the past and will add sweet, spicy notes to beer. However, all parts of the plant are poisonous, particularly the bark and leaves. The berries contain amygdalin, but are considered safe to consume when picked fully ripe.

Sugar content: 7%

Eucalyptus ![]()

(Eucalyptus)

Use: Leaves

Aroma/flavor: Menthol, woody

In 1847, British botanist John Lindley wrote that the tree “furnishes the inhabitants of Tasmania with a copious supply of a cool, refreshing, lightly aperient liquid, which ferments and acquires the properties of beer.” A tree could produce four gallons of sap a day that would begin fermenting as it dripped down the tree. There are more than 600 species around the world, but the Tasmanian blue gum that originates in Australia also thrives in coastal California, particularly in the San Francisco Bay area. The leaves provide the trees’ distinct scent—woody, minty, hinting of menthol—and are used to flavor bitters, vermouth, gin, and vodka. Added at the end of the boil the leaves provide the same aromas in beer, but will turn medicinal if too much is used.

Fragrance essentials: Top notes; contains citronellol, pinene

(Ficus carica)

Use: Fruit, leaves

Aroma/flavor: Dark fruit

Although it was the original “forbidden fruit,” edible fig was one of the first plants cultivated by humans, probably before wheat, barley, and legumes. What’s referred to as the fruit is a syconium, also known as a false fruit or a multiple fruit, but that doesn’t matter to anybody eating the figs or using them to make wine, liqueur, brandy, or beer. Fig flavor in beer is often compared to plums or raisins, but the range of flavors is broader. For instance, Black Mission figs are sweet and gummy, Calimyrna tastes of honey and butterscotch, and Ronde de Bordeaux offers berry notes and a higher degree of acidity. Fig leaves smell spicy, sometimes thyme-like and other times of ribes—all aromas that will persist in beer.

Sugar content: 16%

Smoked character: Mild, fruity

Grapefruit ![]()

(Citrus paradisi)

Use: Juice, rind

Aroma/flavor: Citrus

Called the “forbidden fruit,” the tree that produces it—a hybrid originating in Barbados as an accidental cross between sweet orange and pomelo or shaddoc—recently became the citrus du jour, showing up in shandys and radlers (themselves not new, but now Americanized), but also complementing bold citrus aromas and flavors American hops provide. Used in beers in which orange peel is more traditional, such as a witbier, the zest adds an interesting twist.

Sugar content: 6%

Smoked character: Mild

(Psidium guajava)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Floral, tropical

Another “forbidden fruit,” and there are multiple legends in the Philippines about how it originated. In one of them, guava sprang from the grave of a king who had a sour disposition, thus explaining its sweet-sour flavor. That carries over into the beer, but even when the fruit is added at the end of the boil, the unique bold aroma isn’t as strong in beer. The leaves and bark are quite tannic, so not much is needed if used for bittering.

Sugar content: 9%

Smoked character: Flowery, much like apple

Hazelnut ![]()

(Corylus)

Use: Nuts

Aroma/flavor: Nutty, toasty

The disease Eastern Filbert Blight has made growing hazelnut trees outside of Oregon next to impossible in the United States. Much of the world’s production is used in Nutella—which combines sugar, cocoa, and palm oil along with the nuts—and they’ve long been used to make liqueurs such as Frangelico and Fratello. Also known as filberts or cobnuts, hazelnuts contain less oil than many other nuts. They do not need to be toasted before eating or being used in beer, but toasting brings out sweet caramelized flavors.

Hickory ![]()

(Carya)

Use: Bark, leaves, nuts

Aroma/flavor: Woody, nutty

Among the dozen varieties of hickory that grow in the United States, shagbark is particularly easy to find. Its bark practically falls off the tree and is easy to collect. Brewers at Scratch Brewing toast the bark before adding it to beer, but it can also be used to make syrup. To make the syrup, first toast the bark for 20 to 30 minutes at 325°F. Place the bark in a large pot with enough water to cover it. Bring to a boil, lower heat, and simmer for 30 minutes. Add one cup of sugar for every cup of liquid, thoroughly stirring it in. Bring the liquid back to a boil and cook until it is the desired thickness. To use the nuts, roast them to remove oils that might inhibit head retention. The shells may be used for bittering.

Smoked character: Sweet, strong, and because it is so often used to smoke bacon, may evoke memories of bacon

Juniper ![]()

(Juniperus Communis)

Use: Berries, branches

Aroma/flavor: Gin-like, pine, citrus

The berries provide the primary flavor in gin and, historically, in sahti, Finland’s indigenous beer. Of course, there are many varieties, Juniperus californica most common in California, Juniperus virginiana in the east and central regions. Known variously as red cedar, eastern red-cedar, or Virginian juniper, the latter contains small amounts of thujone—the compound prominent in wormwood—but its berries are safe to use. Juniper berries will turn from green to blue when they are ripe. The leaves and twigs of the shrub are steam distilled to produce juniper oil, and that same aroma can be captured in beer by adding branches with 20 minutes remaining in the boil.

Kumquat ![]()

(Fortunella)

Use: Peel, fruit

Aroma/flavor: Tangerine-like

Found in California and south Florida, the fruit is unique because it contains no pith. Kumquats taste much like tangerines, but are tarter. Much of the aroma is in the peel, and is composed primarily of limonene, a compound often found in hops with citrusy flavor. In order to retain that flavor, kumquats, particularly the peels, are best added during fermentation or post-fermentation.

Fragrance essentials: Contains limonene

Sugar content: 9%

(Citrus Limonum)

Use: Rind, fruit

Aroma/flavor: Lemony, sweet-sour

The most popular lemon for bartenders as well as home gardeners is the sweet and juicy Meyer lemon, which is actually a cross between a lemon and a mandarin. Its rind is lower in essential oils than the fruit itself.

Sugar content: 3%

Smoked character: Tangy, citrus, moderate smokiness

Mango ![]()

(Mangifera indica)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Stone fruit, tropical

One of many tropical fruits showing up in a would-be style called Florida weisse in the state of the same name. It is basically a Berliner weisse fermented with fruit, usually tropical and colorful. Mango is one of several brewers are using, and is full of juicy stone fruit aroma and flavor.

Sugar content: 14%

(Acer)

Use: Sap, branches, leaves, bark

Aroma/flavor: Sweet

According to legend, maple syrup once flowed directly from trees. The Abenaki people in the American northeast liked it so much they would lie on their backs and let it drip into their mouths. They were content to get fat and did not tend to their work. For that reason, the creator instructed Gluskabe, who was in charge of teaching them the art of civilization, to replace the syrup in the trees with water. He then told the Abenaki they would have to work for the syrup, boiling it from sap that would flow once a year in the spring. That, of course, is how maple syrup is made today, and it takes 30 to 50 gallons of sap to produce one gallon of syrup. The syrup is one way to introduce maple flavor to a beer, but its branches, leaves, and bark also provide subtle maple-like sweet flavors as well as a measure of bitterness. Brewers with access to the trees may draw their own sap and use it in place of water in a recipe (see birch tree recipe, page 290).

Smoked character: Subtle, sweet, can even hint of maple

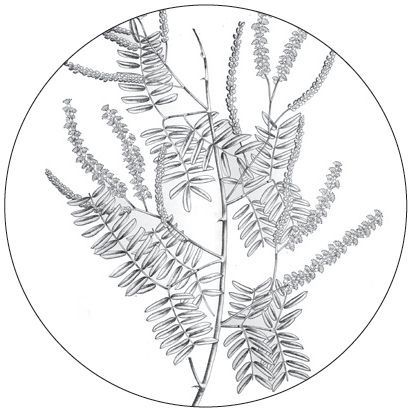

Mesquite ![]()

(Prosopis)

Use: Pods

Aroma/flavor: Toasted bread

In his journal documenting the 1841 Texas Santa Fe Expedition, George Kendall wrote that when “our provisions and coffee ran out, the men ate [mesquite beans] in immense quantities, and roasted and boiled them!” The small trees are ubiquitous in the Southwest, valued for their wood by artisan furniture makers and pitmasters who smoke meat over it. It is no longer used as a food source, but the pods can be used to make syrup to flavor beer. They contain 20 to 50 percent sugar by weight, but no starches and do not need to be mashed. Roasting pods will create melanoidins. To make syrup, harvest the pods when they are light tan and brittle (late June, again in September). Place the pods in the sun or an oven set at 150°F to dry them. Roast mesquite by putting rinsed pods on a cookie sheet in a 350°F oven. Toast 20 minutes for a light roast, 60 for dark. After roasting allow the pods to sit for one to two weeks, then store as any grain. To make an extract from these, break the roasted pods into one-inch pieces and add to water in a 1:4 ratio (one pound of pods to two quarts of water) and heat to 150°F (66°C). Taste occasionally, and when the flavor stops changing turn off the heat. Add the extract at the beginning of the boil. Don’t be tempted to use mesquite beans that have fallen to the ground or that have tiny holes associated with wood-boring beetles. In both cases the beans are likely contaminated with aflatoxin-producing fungus.

Smoked character: Spicy, earthier than hickory

Oak ![]()

(Quercus)

Use: Bark, acorns, leaves

Aroma/flavor: Tannic, vanilla

American white oak has the same flavor compounds found in vanilla, coconut, peach, and apricot, which is why beer may take on so many additional flavors when aged in barrels. Of course, oak is also rich in tannins, and is used for tanning leather. That’s also true of other parts of the tree, so oak bark will provide more tannic character than hickory. Hickory bark, in contrast, is more fragrant. Acorns are often ground to use for flour, but may be roasted and eaten. Acorns should be leached of tannic acid first. Scratch has let acorns ferment for a year before using them. They should be lightly dried, then put in an airtight jar (too wet and they will mold). Fermented, they add intense vanilla and bourbon aromas.

Smoked character: Mild, with little aftertaste; red oak is a favorite of Texas pit masters

Orange ![]()

(Citrus)

Use: Fruit, rind, blossoms

Aroma/flavor: Citrusy, sweet, pithy

Historically, only the peel has been used as a zest to spice beer. It contains several compounds found in hops. There are two species, one sweet and the other bitter. Although the bitter ones are more common in beers such as Belgian Wit, Blue Moon Belgian White is spiced with the sweet Valencia. In addition, sweet blood oranges recently began to show up in more beers.

Sugar content: 8–12%

Fragrance essentials: Contains myrcene, limonene, and linalool

Smoked character: Tangy, hints of citrus

(Asimina triloba)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Tropical, mango

This tree prefers partial shade and rich soils found near river beds, so it is difficult to grow in orchards and is well suited for foraging. Soft green pawpaws grow three to six inches long, making them the largest native fruits. The tree is indigenous to the temperate woodlands of the American east, and was spread as far as Texas by Native Americans. The fruit is richly textured like a banana, but tastes of mango and pineapple. (See Fullsteam recipe, page 292.)

Sugar content: 16%

Peach ![]()

(Prunus persica)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: How do you describe the flavor of peach?

The aroma of peach is as difficult to capture in beer as it is to describe—in both cases because of the many compounds that interact to produce its delicate aroma. Peaches and nectarines are the same species, even though they are regarded commercially as different fruits. As with the apricot, the peach pit is toxic.

Sugar content: 9%

Smoked character: Sweet, woody

Peanut ![]()

(Arachis hypogaea)

Use: Nut

Aroma/flavor: Nutty, woody

Although peanuts are similar to tree nuts such as walnuts and almonds, they’ve become something different for brewers intent on capturing the flavor of peanut butter in beer. Quite often brewers use peanut extract or peanut butter powder, in part because of their fear of what the nut oils will do to head retention. Because nut allergies are common, brewing with nuts requires scrupulous cleaning before the equipment is used to make other beers.

(Pyrus)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Stone fruit

The taste of pears in alcohol is more familiar in perry, or pear cider, than it is in beer. One of several reasons that perry is much less common than cider is that pears must be fermented almost immediately after they are picked. Like apple seeds, pear seeds contain small amounts of amygdalin (see warning, page 158).

Sugar content: 10%

Smoked character: Subtle, much like apple

Pecan ![]()

(Carya illinoinensis)

Use: Nut

Aroma/flavor: Nutty, sweet, or toasty (depending on preparation)

The tree produces the only major tree nut that grows naturally in the United States, which harvests more than 80 percent of the world’s crop. Texas made it the official state tree in 1919 (and later pecan pie the official state pie) and the trees are particularly prominent throughout Hill Country. (512) Brewing Company in Austin roasts the pecans before using them in Pecan Porter (recipe page 294).

Smoked character: Pungent, nutty

(Diospyros)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Ripe fruit, sweet

According to folklore, the seed of a persimmon can be used to predict the weather, with heavy snow expected when the seed is spoon-shaped. More folklore suggests frost is required to make it edible, because otherwise it is very astringent. However, fully ripened fruit found on the ground is sweet, juicy, and delicious well before frost arrives. It is abundant in much of the southeastern United States, and was one of many fermentables early colonists used in making beer. D. virginiana would be the type early colonists used, while D. texana is smaller, with dark purple-black skin, and tastes almost like chocolate custard when it is ripe. Both types are ripe when their “crown” easily separates from the fruit.

Sugar content: 13%

Pine ![]()

(Pinus)

Use: Branches, nuts, inner bark

Aroma/flavor: Christmas, nutty

Grown primarily for timber and wood pulp, pine is also harvested as Christmas trees and the branches can be used to bitter and spice beer. Roasted pine nuts add flavor to beer, as well as the toasted inner bark (cambium layer) of certain pines, such as the Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and white pine (Pinus strobus). Both of these pine tree cambium layers are high in flavors such as vanilla.

(Prunus)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Plum, cherry

The American plum, sometimes called wild plum, grows over a wide swath of the country and is also found growing wild. Wild plums are much smaller than those in grocery stores, and generally not as sweet. The skin is particularly tart while the meat or flesh of the plum runs sweet. It often tastes of cherry as well as plum. While plum pits are not the most toxic, they are similar to apple and pear seeds.

Sugar content: 10%

Smoked character: Mild, sweet

Pomegranate ![]()

(Punica granatum)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Juicy, tart

Grenadine was originally made from pomegranate juice, sugar, and water. Beer brewed with the juice often turns deep red to purple, and has the same rich color and much of the same flavor as the fruit. It can be sweet or sour, its high level of acidity providing a pleasant balance in sweeter beers.

Sugar content: 12%

Spicebush ![]()

(Lindera benzoin)

Use: Leaves, branches, berries

Aroma/flavor: Turmeric, ginger

Different than the spicebush grown on the west coast, the bright red fruit of this woodland shrub was used as a substitute for allspice during the Revolutionary War. Over the years the name changed from allspice bush to spicebush. The leaves and branches may be used for bittering, while the spicy berries taste similar to turmeric and lend a red cast to beer.

(Picea)

Use: Tips

Aroma/flavor: Floral, resinous, camphor-like

Colonial brewers used spruce tips as a substitute for hops, and later Captain James Cook made a molasses-based beer with spruce that was intended to combat scurvy. Although spruce tips contain vitamin C, scientists know now that as a result of boiling and fermentation spruce beer contains no vitamin C. There are more than 30 varieties, with Sitka spruce being highly valued for its aromatic tips. Beware that several varieties of spruce look much like poisonous conifers such as yew.

Star Anise ![]()

(Illicium verum)

Use: Fruit

Aroma/flavor: Anise, licorice

The star-shaped fruit, which may have up to 10 points, and the tree share a name, and as it would suggest the fruit smells much like anise (and licorice). The trees grows in China, Vietnam, and Japan, but have been successfully cultivated in the United States. Shortages have occurred because the pharmaceutical industry buys most of the crop to make a drug that combats influenza outbreaks. Anise and licorice make perfectly suitable substitutes.

(Rhus)

Use: Drupes, leaves

Aroma/flavor: Citrus, spice

The small trees grow over much of the United States, although it is known by other names, such as squawbush, in other regions. Traditionally, the fruits, called drupes, were ground into a reddish-purple powder that is lemony and spicy. Leaving the seeds in during grinding will add a slight bitterness to the powder. The drupes were also used to make “Indian lemonade” (or “sumac-ade”). They are simply soaked in cool water, with sugar added to taste. Added at the end of the boil the leaves and fruits will contribute a reddish color and lively lemon character without the sourness that may develop if they are boiled. The tender tips of new branches can also be used to give an aromatic flavor. Poison sumac may be identified by its white drupes, which are quite different from the red drupes of the desirable trees.

Sycamore ![]()

(Platanus occidentalis)

Use: Sap, leaves

Aroma/flavor: Nutty (sap)

The tree is closely related to maple, and like maple its sap can be used as a substitute for water or reduced to syrup. Its inner bark is stringy and not as pleasant-tasting as maple’s, but it is abundant and can be toasted. The leaves will add bitterness or can be used post-boil to contribute a light, sweet aroma. Also known as buttonwood and water beech.

Tamarind ![]()

(Tamarindus indica)

Use: Pods

Aroma/flavor: Apricots, dates

Probably indigenous to Africa, the tree has many uses and is grown worldwide in tropical and subtropical zones, including South Florida. Its pod fruits are also called tamarinds. As they mature, the pods fill with a juicy, acidulous pulp that eventually dehydrates into a sticky paste. The level of sweet and sour varies, but even a variety the USDA labels “Manila Sweet” is a bit tart. It has been described as tasting of lemon, apricots, or dates.

(Citrus tangerina)

Use: Fruit, rind

Aroma/flavor: Boldly citrus

The fruit is classified as a mandarin orange under one system, as a separate but similar species under another. Tangerines are smaller, sweeter, and have stronger flavors than common oranges. Like oranges, their peel is used as a spice and will add bitterness.

Sugar content: 9%

Walnut ![]()

(Juglans)

Use: Nuts, bark

Aroma/flavor: Nutty, earthy

Milder tasting English, or Persian, walnuts are the ones most often found in stores. Black walnuts, which were harvested by Native Americans at least 3,000 years ago, are bolder and earthier with shells that are difficult to crack. Of the world’s harvest of black walnuts, 70 percent comes from trees growing wild in Missouri, and 45 percent of that will be used in ice cream. Quite obviously, Missouri is the place to forage for wild walnuts. Black walnut trees are very valuable, with mature trees fetching thousands of dollars from lumber yards. Pulling bark from a tree you don’t own is the antithesis of good foraging (see good foraging tips on page 118).

Smoked character: Black walnut wood is hickory’s stronger cousin—intense, even bitter; English walnut is less intense, smoky

Willow/Red Willow/White Willow ![]()

(Salix)

Use: Bark, twigs

Aroma/flavor: Woody, earthy (often bitter)

Salicin, the active ingredient in willow bark, seems to have contributed to the death of the composer, Ludwig van Beethoven. Apparently, Beethoven ingested large amounts of salicin shortly before he died. His autopsy report is the first recorded case of a particular type of kidney damage that can be caused by salicin. Purple willow contains the highest concentration of salicin, but white willow is second and much more pleasant tasting. The warning is included here as a reminder that willow bark isn’t for those who should not take aspirin. Nonetheless, it has commonly been used as a pain reliever since the time of Hippocrates.