If only Lockwood could be untethered from the world, set loose to float somewhere safe, if only all the terrors of the war could be swept away. If only Hetty did not have to leave one day, when the museum did.

I was used to any moments of happiness, any months of contentment, being dashed by nerves and nightmares, and so I tried to remind myself to savor every minute with Hetty, basking in the warmth of her love, our little cocoon of joy and pleasure.

I reveled in getting to know another body just as well as I knew my own—the soft hollow of her belly when she lay down; the angle of her hip bones, like pottery shards; the whorl of the grain of hair between her thighs; a scar on her shin with dots where a doctor had made his stitches; her lopsided rib cage. She had moles that speckled her body like decorations from some absentminded god—one on her left breast, five on her stomach, a row down her left calf, one on her backside, and two on the nape of her neck. When I was studying her body, when she was studying mine, and making me gasp and shake, there was no room in my head for worries and fears.

I had tried to teach myself to ignore things that might not be real, to rationalize huddled shapes that I saw in the corners of a dark room or the whisper of the wind that sounded like dragging footsteps in the hall, to tell myself that dreams were just dreams, so is it any wonder that I had been trying to push down my true feelings for Hetty, trying to tell myself that any romantic love, desire, that I thought hummed between us was just another phantom? And just as that hidden attic room had been revealed as truth, so had Hetty’s feelings for me—except one was a gut-wrenching, painful truth and the other was luminous, thrilling, revelatory, heavenly. Was this why every husband I had tried to imagine had been as shadowy as a spirit and as unsatisfactory as a puppet?

I thought that I had ruined everything that night we slept in the drawing room, that I had made her uncomfortable with my advances. But then to have her turn up at my door, trembling and so very brave; to think of how the stars had to be aligned for the director of the museum collections evacuated to Lockwood to also be the woman I fell in love with, who fell in love with me in return, astonished me.

Was I too happy now? Would this all come crumbling down? Would my bad nerves prove too much for her, my nightmares?

The air-raid sirens were like a knife slicing through our pleasant afternoons, our bucolic evenings; the rudest interruption of the outside world; a horrid reminder that I had responsibilities beyond Hetty—responsibilities to the house and its inhabitants. Each time the siren blared, it seemed to demand an accounting from me, like the roar of some wailing beast rattling against the walls of the house. How was I going to keep them safe; how was I going to protect Lockwood?

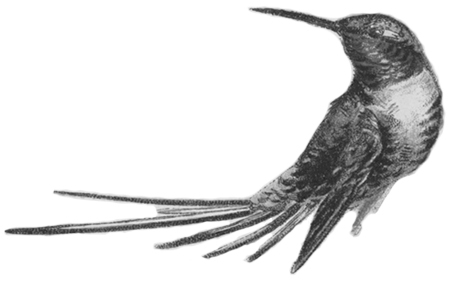

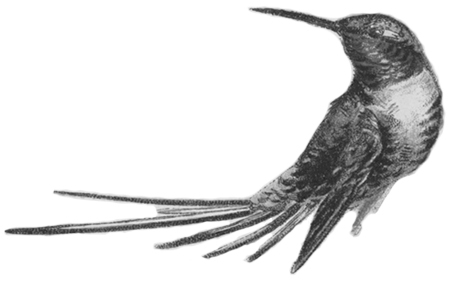

Or was the noise of the siren, I sometimes wondered—as I woke panting from a nightmare, convinced that I had heard the same sound blaring through my dreams—the roar of a beast inside the house braying to get out? Some monstrous creature trapped in another hidden room, its hackles bristling with hot fur, its teeth bared. For the siren blared within the walls of Lockwood itself, did it not? As if the true danger was inside those same walls, and not from the planes gliding through the sky so high above us.

And when I emerged from sheltering in the basement, fleeing toward the light of the day, I could not shake the notion that someone had been in the upper levels of the house, stalking through the corridors, rifling through the rooms, while we were hidden underground. I could not help but notice each time that certain things in my bedroom—clothes, trinkets, books—seemed out of place from where I had left them, and that one day when I had looked in the mirror over my mantelpiece that I knew had been cleaned just before the siren screamed, I saw, in the bright light of the September afternoon, the ghostly outline of a handprint that did not match mine.