JUNE 13, 1891 was to be a day of memories. There could be little doubt that Arabella Weems was in her eleventh hour, with the minute hand racing around to twelve. Before the day was over, any remnants of the weights she had carried for a lifetime would be lifted. There would be no tomorrow here, but for the faithful there was the promise of happiness elsewhere. Her second son, Dick, would be waiting for her. How could he not be? Perhaps his imperfect body would be healed, allowing him to join in with the other children as he never could in life. Stella, whose final wish was that she could see her mother again, would be there too – her request at long last answered. And also little Sylvester, whose time had been cut far too short by the aftereffects of a slave coffle under an unforgiving Alabama sun. Had he lived, he would now be forty. Instead he would be forever three.

Just as she had previously rejoiced over being reunited with the remainder of her boys, she had once more felt the pain of separation from each of them: first Augustus, then Addison, then John Jr., then Joseph. Augustus, like Sylvester, had died in the first year of his freedom. Medical treatment at the time was no match for his affliction, initially thought to be consumption. He was only twenty-two. Dr. Rumph had indeed made the financially wise decision to sell while he could. Caveat emptor: Buyer beware. John and Arabella Weems, who had been cheated out of spending five years with their son, were at least able to spend his final days with him. Despite their having had a bit of time to prepare for the upcoming grief, it was not enough – it never is. On November 24, 1858, less then three months after John Weems had registered the free papers for Augustus in Washington, and one day after his death, his parents buried him in an unmarked Canadian grave. Father Jaffre of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in Chatham officiated at the funeral.1

For the next decade, the remainder of the family, with the exception of Catharine, struggled on in Canada, revelling in their freedom, despairing at their losses, and often thinking of home. They were uncertain how the election of Abraham Lincoln would affect the United States but would have been delighted to learn that Jacob Bigelow, who took life-long pride in his role in freeing Ann Maria, had been selected as an assistant marshal to escort the president elect to the Executive Mansion at his first inauguration.2

Bigelow’s appointment was in recognition of his role as a prominent delegate and permanent committee member for the Republicans as the party campaigned for justice and for the end of slavery.3 He had found additional happiness in his marriage on July 25, 1859, to Rebecca M. Ogden, who looked upon her husband with immense pride as he passed in the colourful procession wearing a pink scarf with white rosettes, aboard a horse adorned with white saddle covers trimmed in pink and carrying a pink baton tipped in white.4 Sadly, Jacob Bigelow died during Lincoln’s first term in office and was denied the opportunity to witness the greatest of the president’s accomplishments.5 However, his widow carried on Bigelow’s charitable legacy as an officer and donor to the National Association for the Relief of Colored Destitute Women and Children.6

John and Arabella watched the War of the Rebellion, as the Civil War was originally called, from the vantage point of British North America, which sent fifty thousand of its sons to southern battlefields – some for adventure, some for profit, others for larger ideals. But in the end they all went to settle the issue of slavery, whether they consciously knew it or not. Even President Lincoln acknowledged that one of the people most admired by the Weems family, Harriet Beecher Stowe, had played an important part in taking the first steps to remove the stain of slavery from their country, when he reportedly greeted the author by saying, “So this is the little lady that started this big war.”

As soon as blacks were allowed to enlist, dozens of men from the area where the Weems family lived returned to the United States and joined the Union Army. Several fought with the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment at the bloody attack of Fort Wagner. Many were killed in battle, but their bravery quieted the stereotype that blacks had neither the will nor the ability to serve as soldiers. (courtesy of Buxton National Historic Site and Museum)

Arabella and her sister Annie surely devoured any information they could find about how the war was affecting their homeland. During the first two years of the war, the news was not comforting, with mounting Union Army losses to the Confederate forces. Familiar names were in the news that wafted its way to the small Canadian black settlement.

In 1861, at the outbreak of hostilities between north and south, slave owner Dr. Charles A. Harding – for whom the Weems family no doubt felt that Hell must hold a special place – was part of a delegation of the Maryland legislature who travelled to Montgomery, Alabama, the first capital of the Confederacy, to meet with President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. They were cordially welcomed. Davis greatly appreciated receiving the assurance that the “State of Maryland sympathises with the people of these States in their determined vindication of the right of self-government.” Even though the state had not yet seceded from the Union, Davis expressed his hope that Maryland, “whose people, habits and institutions are so closely related and assimilated with theirs, will seek to unite her fate and fortunes with those of this Confederacy.”7

Maryland officially remained loyal to the Union but many – including Harding, who joined a Confederate regiment – made no secret of where their true loyalties lay. Indeed, of 653 ballots cast in the 1860 presidential election, Abraham Lincoln had not received a single Rockville vote.8 Harding had been appointed assistant surgeon for the Union Army’s First Maryland Infantry, but declined, instead enlisting as a private in Company C of the Second Maryland Cavalry before eventually achieving the rank of major and quartermaster for the Confederate States of America.9 His brother-in-law, Robert W. Carter, had spent some time in the Capitol Prison in Washington during the war for providing aid to the enemy.10

Lieutenant John Newland Maffitt, who had accepted the money for Diana Williams that had been originally intended for Augustus Weems, feared that he might be called upon to bombard his home state of North Carolina after war was declared. He resigned his commission in the United States Navy and became infamous as a Confederate Navy commander who patrolled the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, running the Union blockade of southern ports and capturing and sometimes destroying her ships. Maffitt even ventured into the English Channel to capture a ship laden with coal that was bound for the northern United States, putting both the vessel and her cargo to the torch.11 By summer’s end of 1863, he boasted of having captured seventy-two ships worth fifteen million dollars.12

The war was costly on all fronts. It would cause Dr. James Rumph to feel acutely the anguish that the parents of his former slave, Augustus Weems, had suffered. Three of Rumph’s sons fought for the Confederacy. Langdon, the youngest, was struck by typhoid fever. An embittered Dr. Rumph never forgave those whom he thought were responsible for the misery caused by the war, confiding to his journal: “Mr. Lincoln and his cabinet are responsible for all the sufferings, cruelties, carnage, murders, and deaths of this fratricidal war; yes every drop of blood spilt, wound received, sickness received in camp and hospitals where so many languished and died for want of freedom and food, peace and home and liberty.”13

Not all of the disturbing Civil War reports that reached the Weems family came from the battlefront; some hit closer to home. When the draft was instituted in the North, the city of New York erupted in riots to protest the increasingly unpopular war. Blacks were the objects of the rioters’ wrath. The “colored” orphanage was burned to the ground, several people were killed, and many more were left battered and homeless. The high-profile abolitionist Reverend Henry Garnet was targeted. Fortunately Mary, his quick-thinking daughter, had removed the brass nameplate from their front door with an axe, leaving the mob uncertain who lived there. White neighbours concealed Garnet and his family until the trouble passed.

Some good news also floated north to Canada’s freed slaves. Justice was finally taking notice of the hated slave traders Cook & Price. Newspaper accounts showed that John Cook was up to his familiar tricks: he had recently preyed on the soft hearts and generosity of abolitionists by demanding nine hundred dollars for nine-year-old Sally Maria Diggs, affectionately known as “Pink,” so that the little girl would not be separated from her grandmother.14

A later news item, printed after the Civil War disrupted the coastal voyage of the slave ships to New Orleans and other southern ports, was unconditionally satisfying. John Cook had placed a slave named Jane Coucy in a Baltimore slave pen for “safekeeping” for a period of sixteen months, apparently to ensure that she would not be freed if the rumours that President Lincoln might free the slaves in the District of Columbia proved correct. In an unexpected development, soon after the bloody battle of Gettysburg, Union soldiers arrived at the high wall that enclosed the two-storey brick building with orders to free everyone held within the slave pens of the city. Besides Jane Coucy, they found fifty-five men, women, and children, including infants who had been born there. The army commander ordered a blacksmith to remove the shackles of those who were in chains. As the suddenly freed slaves walked out onto the street, many were met by surprised and jubilant loved ones. The men in the group followed the soldiers to the colonel’s headquarters and enlisted in the Second United States Colored Regiment, thereby helping to close all of the southern slave pens.15

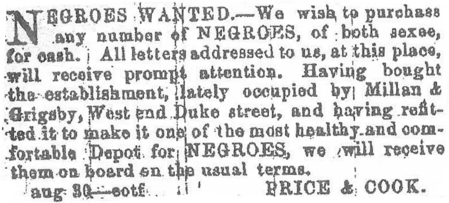

John Cook’s misfortunes paled in comparison to what happened to Charles M. Price. Cook & Price continued to advertise “Negroes wanted” in the Gazette well into 1861, even though Price had purchased Cook’s interest in their Alexandria slave pen on January 17, 1860, for $2,500 and the business had been renamed Price & Birch.16 The August 11, 1862 edition of the Gazette carried an advertisement that Price & Birch had relocated to a slave pen in Culpeper, Virginia.17 Charles Price very naturally supported the Confederacy, which represented the only hope of his maintaining his lifestyle and business. Doing his part, Price allowed the rebel cavalry to occupy his fortified slave pen in the early days of the war, but their occupation would be short-lived. On the morning of May 24, 1861, while having breakfast, the southern soldiers were surprised by the Union Army, which captured both the building and its inhabitants. Price fled deeper into the heart of Virginia, outraged at the loss of his property to the enemy.18 At times during the Civil War, Confederate prisoners of war were held in Price’s cells, once reserved for slaves destined for the auction block. Newly freed men took pleasure in pointing out to prisoners that their positions had been reversed.19

Charles M. Price and John C. Cook revived their slave-trading partnership from the previous decade, as witnessed in this Alexandria Gazette ad from November 1, 1860. (Library of Congress microfilm)

In a disingenuous attempt to seek compensation for his loss, Price drew up a bogus deed dated June 1, 1861, turning over the property to his brother-in-law and fellow slave-trader, Solomon Stover, who feigned his support for the Union. The pair also registered a deed in Montgomery County, Maryland, recording that Price had sold eight slaves, six horses, a buggy, and several household articles to Stover.20 Seeing through this ruse, the Senate committee that reviewed compensation claims for properties seized or damaged by the Union Army firmly rejected the application, stating: “You allowed the organized military forces of the enemy to occupy and use this property; it was captured from them within enemy’s lines. You yourself was a rebel, abandoning your home in a loyal State, and seeking the protection of the enemy and sojourning with him. You have no standing in court; you can claim no compensation for your property, either its use or damage.”21

None of the news that arrived from Washington would have been as eagerly sought by Arabella and Annie as word about their mother. At times, Cecilia would have been right in the middle of the unpredictable and rapidly unfolding events. During the Civil War, Cecilia’s owner, Jane E. Beall, remained staunchly in favour of the Union; this despite the fact that she and her sisters were large slave owners. Of course, President Abraham Lincoln had made it very clear that it was not a war to end slavery but rather a war to save the Union. In the fall of 1862, the Northern Army of the Potomac set up their headquarters near Rockville. Major General George B. McClellan wrote to his wife telling her of his progress and letting her know that he had found a room in the house of Jane Beall, whom he described “as an old maid of strong Union sentiment, who refused to receive any pay” for her hospitality.22 However, she had recently had no trouble accepting money from the federal government in other ways.

A woman standing beside the Alexandria slave pen that at one time belonged to Charles M. Price and John C. Cook (Library of Congress LC-B811- 2300[P&P])

Earlier that same year Congress had passed “an act for the release of certain persons held in service or labour in the District of Columbia.” The act was extremely controversial. All slaves in the District were to be freed and all of their owners were to be compensated from the public treasury. Word spread like wildfire. On April 16, 1862, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s brother, Henry Ward Beecher, hastily fired off a telegraph to Abraham Lincoln: “The Independent goes to press at 2 oclock PM this day Wednesday. May I say that the district of Columbia is free territory?”23 It was so.

Jane Beall and her sisters were among those who applied under that act for compensation for her slaves who had been hired out and were then living in Washington. Among them was the grey-haired Cecilia Talbot, who had long ago been estimated as past the age of usefulness. Because of her advanced years she was evaluated on May 15, 1847, at fifteen dollars. On Christmas Eve, two years later, at the time of the reevaluation and distribution of Robb’s estate, her value had declined to ten dollars. On February 2, 1852, her age was estimated at seventy-eight and her value had further depreciated to one dollar. Ten years later, when the federal government agreed to compensate slave owners for freeing their slaves in D.C. Cecilia had miraculously gotten eighteen years younger and was now listed at about seventy years of age in the petition for compensation. Her owners, who had shamelessly fudged her age by nearly twenty years, maintained that she was still a good cook and active and healthy.

A Union soldier reads the Emancipation Proclamation to newly freed slaves. After Lincoln signed the proclamation, celebrations took place across the country. (Library of Congress image cph 3a08642)

Associated with the practical side of administering the payments was an irony to beat all ironies. Bernard Campbell, the owner of one of the largest slave-trading empires, was hired by the federal government to use his considerable expertise in determining the proper amount of compensation.24 Among the slaves that he evaluated were those of the Beall sisters. No fools when it came to business dealings, the Beall women contended that although they lived in Maryland, which was not included in the offer for compensation, they had hired out some of their slaves to people in Washington. And they could certainly attest that their slaves had not “borne arms against the United States in the present rebellion, nor in any way given aid or comfort thereto.” Therefore they should collect any money they might be entitled to under the law. On July 11, 1862, when Jane Beall appeared before Campbell, seven of her slaves, including Cecilia, were absent.25

By October 30 Cecilia still had not appeared and the commissioners wanted to know why. The commissioners finally brought in an impartial gentleman named Henry Busey and questioned him about Cecilia’s whereabouts, age, abilities, and general health. They must have been satisfied with Busey’s account, because the Beall sisters were granted fifty dollars in compensation for Cecilia and $9,350 for an additional seventeen slaves that they owned.26 Mercifully, Cecilia did not have to suffer the indignity of being examined by the much-despised slave trader. She had already experienced far too many degradations in her lifetime.

Black citizens in Washington, D.C. celebrated the abolition of slavery in a march outside the White House in 1866. (Library of Congress image cph 3a34440)

The former owner of Cecilia’s son-in-law William Henry Bradley also tried to get compensation for the loss of his slave. In 1864 a new Maryland constitution freed that state’s slaves. Three years later, William Pierce joined with other Marylanders who claimed to have remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War and were therefore entitled to payment for their slaves. After hearing complaints that many slaves had been induced to leave their owners and enlist in the Union army, the General Assembly ordered that a listing be made of all slave owners and their slaves as of November 1, 1864. Pierce deviously listed “Abraham Young,” even though Young had been free in Canada for fourteen years by then. Pierce was unsuccessful in this deceit, and no reimbursement was granted.

Despite some foreboding hints that the racially intolerant status quo was being maintained, there were some promises of equal rights and opportunity. But no inducement to return to the United States was stronger than the desire to be reunited with family. Even though in Canada they were surrounded by relatives and friends, the Weemses had left many other loved ones behind. Cecilia was among those still there and Arabella longed to see her again.

As more settled conditions descended upon the U.S. capital, the lure of home eventually became too strong, pulling John, Arabella, their surviving sons, and Mary, along with Lewis and Mary Jones, back to the familiar surroundings of Washington by 1868.27 They were a part of that great black migration from Canada that came after the Civil War ended. The northward exodus had reversed, just as Reverend Thomas M. Kinnard, a Toronto-based abolitionist and former slave, predicted in 1863: “If freedom is established in the United States, there will be one great black streak, reaching from here to the uttermost parts of the South.”28 The Underground Railroad that had been such an important part in their history was beginning a final journey into the realm of legend.

The Weems family and their friends returned for many reasons. There had been several years of crop failures in Kent County, where they lived. The climate was harsher than they were used to. The winds blew colder there, partly because of latitude, partly because it was not home. Some Canadians had only begrudgingly accepted the former slaves, and once slavery was abolished their discrimination encouraged the blacks to leave. There was also a prevailing feeling that those who had acquired new skills and independence in Canada had an obligation to return to the United States and help with Reconstruction. After all, even old friends in Britain like Anna H. Richardson had answered Lewis Tappan’s appeal to provide woollen worsted and cotton garments for the newly freed but destitute blacks.29 Those who had prospered in freedom should do no less.

And there was a prevailing optimism that there would be new beginnings for all blacks in the United States, with their rights assured and their futures bright. This hopefulness came from some of the Weemses’ old friends who were leaders in the movement for civil rights. Lewis Tappan and Henry Garnet had shared the stage before a large, adoring crowd at an “Emancipation Jubilee” held in January 1863 to celebrate the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation that declared “all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” On February 12, 1865, Garnet became the first African American to preach at the Capitol Dome in Washington. Tappan continued to fight for even the most basic rights for blacks, including ending their exclusion from riding on railroad cars, a ridiculous practice he thought must excite “the loudest laugh in hell.”30

Slavery was completely abolished in the United States of America in December 1865. (Library of Congress image cph 3a06245)

The Weemses would not have been naïve enough to believe that society would immediately change or that all those in positions of power would be sympathetic to their rights. John H. Goddard, who had been the captain of the Auxiliary Guard and the captor of Mary Jones, would still be a force to be reckoned with, after the executive session of the United States Senate confirmed his appointment as justice of the peace for Washington County in the District of Columbia on May 18, 1864. Some progressive senators were opposed to his appointment and appealed to the president to rescind it, but Lincoln, ever the conciliator, declined, stating that the resolution was already “a part of the permanent records of the Department of State.”31

Of course, there were many uncertainties following the traumatic assassination of Abraham Lincoln on Good Friday, April 14, 1865. “Father Abe,” as he was affectionately called by many blacks, was mourned and eulogized at countless memorial services by former slaves on both sides of the border. The Weems family would have been appalled that John C. Cook was chosen to be one of the marshals to march in Lincoln’s funeral procession.32 John and Arabella might have found it more fitting that Cook, as part of D.C.’s murky slave-trading subculture, was called as a witness during the assassination conspiracy trials to testify about the character of one of the suspects.33

Following the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination, Arabella’s mother lived in D.C.’s shanty town district known as Swampoodle with the widowed Charlotte Branham, another former slave of Henry and Catharine Harding’s, who very well could have been one of Cecilia’s daughters. Dependent upon Charlotte’s meagre income as a washerwoman, these two ladies, who had also taken two young children into their home, would have appreciated any assistance that the Weems family could offer.34 The sketchy records leave us to wonder if the children, Charlotte Tompkins aged seven, born in Louisiana and eleven-year-old Fannie Warren from Alabama, might be Charlotte Branham’s granddaughters born to her daughters who had been separated from their mother during slave days.

John and Arabella’s immediate family were confident that they would fare reasonably well in Washington. There were jobs to be had and Addison and Joseph, forever close because of shared blood and experience, worked together there as labourers. The pair initially shared a home on Sixth Street with the rest of the family, and chose to remain together the next year after their parents and siblings moved to John Jr.’s nearby home. However, pitiless fate again stepped in. Addison died on May 17, 1871, at age twenty-eight, after suffering a long illness. He had made a gesture to regain his personal identity by retaking his birth name, Charles Adam Weems. His funeral took place at his residence, 228 New Jersey Avenue.35

John Jr. had certain advantages over Addison and Joseph: he had acquired his freedom at a much younger age, he had never been separated from his mother, he had been apart from his father for only a relatively short time, and he had learned to read and write. John had taken up the carpentry trade and prospered at it. He would have been excited on April 12, 1869, the day that he purchased his first home, thanks in part to the generosity and financial backing of Sylvanus Boynton. He would share it with his parents, younger sister, Mary, and William Saunders, who was a young carpenter originally from Alabama. John Jr. paid one thousand dollars for a property on New Jersey Avenue and within a year it had nearly doubled its value.36 By 1871 he had expanded his carpentry business, basing it from an additional property on Q Street.37 On October 1, 1872, the family moved into a new home at 205 Tenth Street. Just when John Jr.’s future looked promising, he was stricken with a long and painful illness that, according to the local newspaper, he “bore with Christian fortitude.”38 Early in the morning of October 25, 1872, he succumbed. His family and friends gathered for a funeral service for their twenty-two-year-old loved one at St. Joseph’s Church on Capitol Hill two days later.

The Weems family lived in this house on Tenth Street SE in Washington, D.C., when they returned to the United States from Canada. (courtesy of Sandy Harrelson)

Of the six sons born to Arabella and John, Joseph was now the only one remaining. He had risen to the highest social status of the boys, having been appointed by Frederick Douglass to the prestigious position of sergeant-at-arms of the District Council. Young and determined, Joseph fought for the rights that had for so long been denied to him. On one occasion, when he was refused first-class accommodations on the Lady of the Lake because of his colour, he took the boat’s owners to court rather than quietly acquiesce to the injustice.39 He, too, was the recipient of the kindness of Sylvanus Boynton, who loaned him money to purchase a home. Displaying his consideration for the family, Boynton established easy terms, charging no interest and setting up a legal trust so that if Joseph should default on the loan and the land had to be sold at public auction, Joseph would still get whatever money was left after the expenses were paid.40 But everything started to come undone with the death of Addison and the long illness and subsequent death of John Jr. Joseph tried to come to his parents’ aid, moving into the family home on Tenth Street and putting money toward the payment of their mortgage. But yet again it fell to the family’s guardian angel, Sylvanus Boynton, to come to the rescue and hold the house in his trust for the Weemses’ use.41

The Weems family was still reeling with grief from the deaths of Addison and John when Joseph was swept up in the smallpox epidemic then ravaging Washington. Under order of the board of health, Arabella and John would have placed a yellow flannel flag on the house’s exterior, warning all passersby of the disease within. They were expected to fumigate with sulphur three times a day and to disinfect every part of the home with chlorinated soda, carbolic acid, or another approved chemical. They were to hang a one-square-yard cloth in the afflicted person’s room, saturated with disinfectant. No clothing or bedding could be removed from the room that had not been cleaned and disinfected. Only a nurse who had previously had smallpox or a family member (most likely Arabella) was allowed into the room.

Joseph died within eight weeks of his younger brother, John, on December 20, 1872.42 No church service was allowed, and according to city policy Joseph’s body was to be buried within six hours of death. No one other than an ambulance driver, an appointed representative of the board of health, and the immediate family could accompany his body to its final resting place in the Small Pox Cemetery situated near the banks of the eastern branch of the Anacostia River on the grounds of the Washington Asylum.43

At some point in the previous decade, Ann Maria had also died, although it is unclear if her death occurred in Canada or in the United States. After leaving her mark for a brief time in the 1861 books of Dresden’s Anglican church, she slipped away from the surviving public record as stealthily as she had at one time eluded the slave trader who mistakenly thought he owned her for life. Her name does not appear in the 1870 D.C. census with others of her immediate family or in the 1871 Canadian census. Confirmation of her passing came from Mary when she later swore in a legal document that at the time of Joseph’s death in 1872, she and Catharine were the only surviving sisters.44 None of the Weems boys had married and neither they nor Ann Maria lived long enough to celebrate the marriage of their baby sister, Mary, on October 24, 1873.45

In 1872 William Still published his groundbreaking book The Underground Rail Road: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, & C., Narrating the Hardships, Hair-breadth Escapes and Death Struggles Of the Slaves in their Efforts of Freedom, As Related by Themselves. It brought public focus back to the family’s dramatic histories, including the bravery of Arabella in restoring little Willie Chapman to his mother, the daring flight of Lewis and Mary Jones, the redemption of Augustus, and the clandestine help of Jacob Bigelow, Dr. H., Anna Richardson, Ezra Stevens, and Lewis Tappan. It was unfortunate that none of the family was fully able to enjoy their renewed celebrity. They would not have known that Tappan, partially paralyzed after a stroke that left him unable to write, dictated a letter to Still encouraging him to include “one of his most interesting ‘underground’ experiences” – that of the thrilling escape of Ann Maria Weems.46 Most of the Weems family would also never get to enjoy reading their story in a small biography, Sketch of the Life of Rev. Charles B. Ray, that was written by Ray’s daughters. The Weems episode had a very special significance in Ray’s life, and was featured prominently in his biography, which also contained copies of the letters that he had exchanged with Jacob Bigelow and Anna Richardson, as well as mention of Ray’s life-long friendship with Reverend Amos N. Freeman, who had accompanied Ann Maria to Canada and who later aided Arabella in raising money to purchase Augustus.47

The crushing weight of so many bereavements caused John Weems’s health to deteriorate, as it did for Cecilia, who also suffered the infirmities associated with advanced age. When her son-in-law tried to have her cared for, the Evening Star provided its readers with an insensitive chuckle at John’s expense. The headline sarcastically blared, “OVER THE HILL TO THE POOR HOUSE; A Centenarian Mother-in-Law Sent Down to It.” The article said the “colored man” John Weems, who appeared to be about seventy-five years old, had travelled to police headquarters to appeal for the admission of his mother-in-law to the poorhouse hospital. He stated that she could not walk or look after herself in any way. Little wonder, as John told the officials that to the best of his knowledge she was 126 years old! When asked what her name was he replied that it was “Cecilia something” – he did not recall her last name, because, in his words, so far as he knew, she had never been married. John was sent away with the instruction to return only after he could provide her surname. John came back later armed with the name: Talbot. With that, Cecilia was admitted to the hospital, commonly referred to as the “almshouse.”48

Cecilia lived another four months before succumbing to old age and “senile debility” at the Freedman Hospital on September 16, 1875. No one seemed to know her exact age; her death certificate recorded it as one hundred years. There was no disputing that Cecilia had lived long enough to see herself and all of her descendants finally and forever free.49 Many of the loved ones who had been in and out of her life while she was enslaved had returned to her.

Arabella and John had many wounds in their lives, but their pain was partially soothed by the arrival of grandchildren. Mary and her husband, James, remained living in their tiny house, where their children filled the rooms with life. The couple thoughtfully paid tribute to Mary’s father and brothers by naming their first son John Albert Savoy, born on March 26, 1875, and their second Charles Sylvester Savoy, born October 15, 1877. The baptisms of the children at St. Peter’s Church were particularly special because the children’s aunt, Catharine Weems, was able to attend and serve as godmother both times.50

John Weems spent his final days working as a gardener, raising plants from the soil as he had always done.51 He and Arabella probably walked the few short city blocks to be a part of a huge assembly at the emotional speech given by Frederick Douglass at the unveiling of the Lincoln Emancipation statue and to remember Henry Highland Garnet, who had been active in the fundraising.52 But John’s time was growing short. At seventy-seven years, seven months, and four days, he had lived a long and eventful life. He passed over at eleven-thirty in the morning on May 30, 1878, in the Washington home that his son and namesake had purchased nine years before. John’s final suffering, from gastritis, was lengthy and painful. But the Evening Star indicated that he had regained his faith and had borne his agony “with a Christian fortitude.” A requiem mass was celebrated in the basement of St. Peter’s Church.53 The lower part of the church was reserved for black members who were barred from the main sanctuary.54 John was buried in the same hallowed ground as Cecilia, at the District of Columbia’s Roman Catholic Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Now without her life’s partner, Arabella needed to be around her remaining family more than ever. As an unselfish expression of the love that they bore for Catharine Weems and all of her family, the Boyntons brought Arabella into their New York City home for a short time, so that she could finally live and heal her grief under the same roof as her daughter. She surely found some measure of joy in the births of more grandchildren: Augusta Weems Savoy, born November 16, 1879, Joseph O. Savoy, born November 21, 1881, and Lydia Savoy, born November 23, 1882.

When she returned to Washington, Arabella was perhaps able to spend some time with her extended family, Charlotte Branham and Mary and Lewis Jones, who were all living in D.C. Since coming home from Canada, the Joneses had moved around considerably, sometimes living apart from each other, as their work demanded. Lewis had various jobs: as a labourer, driver, and janitor. Mary found work as a servant, doing the work she had been trained to do as a young slave. Made of sturdy stock, they both worked at the D.C. Temperance Hall – he as a cook, she as a washerwoman – when they were in their late seventies.55

When the mulatto couple’s age finally caught up with them, they moved together into a home for the aged run by the Little Sisters of the Poor, an order of nuns from the Motherhouse in St. Pern, in Brittany. The home on H Street was opened in February 1871. The Sisters, who were unable to speak English, quickly busied themselves with begging missions for food and supplies and were amply rewarded for their efforts by the generous Washington public. It was another nine years before the Sisters, after consultation with the archbishop, decided that blacks were as entitled to their charity as whites. However, in keeping with the times, it was decided that blacks should live in a separate building. On June 30, 1881, the Sisters, thanks to generous donations, purchased an adjacent small frame house and opened it as an asylum for African Americans. Mary and Lewis Jones were among the first inhabitants after the “colored” home opened in November of that year. To celebrate, a day of feasting and blessings was held for the inmates of both races. Being Catholic, Mary and Lewis would have been able to receive the sacrament of confirmation that was administered by Archbishop Gibbons to thirty of the residents. The Joneses would have cheered in 1882 when Congress ordered that an alley separating the white and black homes be opened to allow a covered passageway to be built to join the two.56

The aged couple enjoyed the comforts of the home and the care of the devoted Sisters. Both died of heart disease after illnesses that lasted six months, Lewis at age eighty-four, on April 25, 1882, and Mary, aged seventy-eight, the next year on September 16, 1883.57 Charlotte Branham’s constitution was more remarkable than either of the Joneses’ or even Cecilia Talbot’s. Charlotte also later spent her final months at the Little Sisters of the Poor, surviving Mary Jones by eighteen years and living until the ripe old age of 104.58

Arabella spent her final years surrounded by her daughter Mary and her many grandchildren. Unfortunately Arabella did not get the chance to see her last grandchild. Mary was pregnant with the fittingly named James Raymond Boynton Savoy when her mother was stricken with her final illness, breast cancer. Arabella joined her host of loved ones who had gone before on June 13, 1891, at the age of eighty-four.59 The Evening Star made no mention of her remarkable life, only that a requiem mass would be held at St. Peter’s Church, and that she had borne, as had her late husband and son, her painful, year-long illness “with Christian fortitude.”60 No one who had known Arabella would expect anything less. She too was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery, with no stone to mark her spot.

Annie and William Bradley spent the rest of their lives in Canada. At the time of Arabella’s death, Annie, then widowed since the mid-1880s, was living in a Dresden home with one of her sons. The sixty-eight-year-old woman was now raising three of her daughter’s children. Granddaughters Viera and Elva Smith were twelve and eleven respectively; grandson William was ten. Although raised a Roman Catholic, Annie converted shortly after arriving in Canada. She joined the British Methodist Episcopal Church, so renamed from the original African Methodist Episcopal Church in honour of the British government, which had afforded a place of refuge for thousands of freeing slaves like herself. In her final three years, she suffered from chronic heart disease until a sudden heart attack took her at ninety-two. Annie had outlived her elder sister by twenty-two years. At the time of her death on Friday April 18, 1913 she was survived by three daughters, two sons, twenty-two grandchildren, and twelve great-grandchildren. The funeral cortege left her home the following Monday, taking her to the funeral service at the BME church, then on to the cemetery of the former British North American Institute on the old Dawn Settlement grounds, where she was laid to rest.61

Catharine Weems, who had been the first of the family to be redeemed by the largesse of abolitionist supporters, spent most of the remainder of her life in the household of Sylvanus Boynton, where she had been taken “temporarily” so she could get used to freedom. The mutual affection that grew between her and the Boyntons was genuine and deep. Loyal and profoundly religious, Catharine repaid the family’s kindness. She remained with Sylvanus through good times and bad – when he was falsely accused of stealing money from the treasury department, after the death of his first wife, Eliza, and through years of emotional and financial disappointments when stonewalling politicians prevented him from establishing a railway in Panama. Catharine stayed devoted to him during Boynton’s brief and disastrous second marriage to a neglectful woman “who constantly associated with people of bad character … drank intoxicating liquors to excess … abandoned her home and spent time in dissipation … has been guilty of adultery.”62

Later the aging Sylvanus, whose investments had made and lost him fortunes, turned over to Catharine the legal title for the Weems family home in Washington. In a shaky hand, he wrote that he did this “especially for over forty years of continuous service rendered to the said party of the first part and to his family, for which no adequate compensation has been or can be made, and in consideration of the fidelity, loyalty and devotion of the said Catharine Weems to the party of the first part, and, especially as the nurse and God Mother of Henry D. Boynton, recently deceased, the son of the said party of the first part, and, for the love and affection the said Grantor herein bears and entertains for the said Grantee.”

Catharine moved to the house in her later years, and considered it to be rightfully hers. Never married, Catharine left money in her will to the religious organizations that had meant so much to her in her lifetime, some of which she became associated with by virtue of her travels and her relationship with the Boyntons. To St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Elyria, Ohio, she bequeathed three hundred dollars. It was in this church’s cemetery that Eliza Boynton was buried in 1897 and her husband, Sylvanus, in 1912.63 Catharine gave a similar amount to St. Cyprian’s Colored Catholic Church in Washington, where she, Mary, her nieces and nephews worshipped in later years. She gave one hundred dollars to Washington’s Little Sisters of the Poor for the Catholic home for the aged where her uncle, Lewis Jones, and two aunts, Mary Jones and Charlotte Branham, spent their final days. Two hundred dollars was directed to the Oblate Sisters of Providence, who ran St. Ann’s Academy of Washington. Another three hundred dollars was given to St. Ann’s Orphan Asylum. St. Peter’s, the Washington church where her parents’ funerals were held, was given one hundred dollars “for the purpose of having Masses said for the Souls in Purgatory.” Whatever was left in the estate was to go to St. Joseph’s Male Orphan Asylum and to St. Vincent’s Orphan Asylum. A bequest of one hundred dollars to St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Rockville, Maryland offers an interesting insight into Catharine’s soul. This was the church of her youth, where she and her siblings had been baptized, where her parents had been married and her grandmother confirmed, where they all, as slaves of Adam Robb and later of Catharine and Henry Harding, sat in the “negro pews.”

Catharine must have been able to recall a thousand excruciating memories from that time in her life. The Harding family had been the source of many of them. Catharine and Henry Harding and their children bore the responsibility for separating the Weems family and changing their lives forever. But however bitter those memories were, they were the only ones that she possessed. As Josiah Henson had once written, his brother who was once held by the same master as the Weems family had his mind “demoralised or stultified by slavery.” Yet another slave who had fled to the safety of Canada lived in dread of ever seeing his master again for fear the man had magical powers that could transport him back to the South. Those effects did not easily disappear with the Emancipation Proclamation or the passage of the amendment to the Constitution that permanently put an end to slavery.

Catharine Weems had been freed in 1853. Her mother, her sister Ann Maria, and five of her brothers had been sold to the slave traders by the Hardings a year earlier. A stipulation of the sale was that none of the family could be resold anywhere in the vicinity of Washington, D.C. This clause was intended to ensure that the family would never be together again or near other loved ones or familiar surroundings. One might have thought that any attachment that Catharine once had to the Harding family was severed forever as a result, but such was not the case.

Mary and Catharine had for several years shared the house that Sylvanus Boynton had purchased. Mary, the youngest Weems child, had experienced an unhappy marriage with James Savoy, whom she accused of being abusive and adulterous. James worked as a barber at the House of Representatives and, despite the fact that he made a respectable wage, he never established his own household for his wife and six children nor, according to Mary, did he contribute to the Weems household expenses, even when requested to do so by his father and mother-in-law before their deaths. Finally, after twenty-nine years of marriage and two years of desertion, Mary filed for divorce.64

Throughout her entire life, Mary never left the family home. Now unencumbered by a husband who could make any marital claim on the property, Mary contended that since she and Catharine were the only two surviving Weems children and that none of her siblings ever had children, not to mention that she had regularly contributed to paying the household expenses, she was the legal co-owner. But Catharine felt otherwise. Before dying, Catharine turned the house and property over to J. Maury Dove and Nannie C. Dove – the granddaughter of Catharine and Henry Harding. Mary, the only of the Weems children to have never been enslaved, fought this transaction in the courts for years. She contended that Catharine’s mind had become unsound and that the Doves had used “undue importunities, persuasions and suggestions” to influence Catharine. Furthermore they employed “fraud, misrepresentation and artifice.” Upon Catharine’s death, the Doves demanded that Mary vacate the home. A defiant Mary, ultimately with the court’s backing, refused to do so.65

A half-century earlier, Catharine and Henry Harding considered the Weems family and all that they may have possessed as theirs. Such was the law of the times. As the nineteenth century came to an end it would appear that the Hardings’ granddaughter felt the same.66 Perhaps little had changed. Slavery’s shadow remained on the household long after its glow was extinguished.