Access to health care is the ability to obtain health services when needed. Lack of adequate access for millions of people is a crisis in the United States.

Access to health care has two major components. First and most frequently discussed is ability to pay. Second is the availability of health care personnel and facilities that are close to where people live, accessible by transportation, culturally acceptable, and capable of providing appropriate care in a timely manner and in a language spoken by those who need assistance. The first and longest portion of this chapter dwells on financial barriers to care. The second portion touches on nonfinancial barriers. The final segment explores the influences other than health care (in particular, socioeconomic status and race) that are important determinants of the health status of a population.

Ernestine Newsome was born into a low-income working family living in South Central Los Angeles. As a young child, she rarely saw a physician and was behind on her childhood immunizations. When Ernestine was 7 years old, her mother began working for the telephone company, and this provided the family with health insurance. Ernestine went to a neighborhood physician for regular checkups. When she reached 19, she left home and began work as a part-time secretary. She was no longer eligible for her family’s health insurance coverage, and her new job did not provide insurance. She has not seen a physician since starting her job.

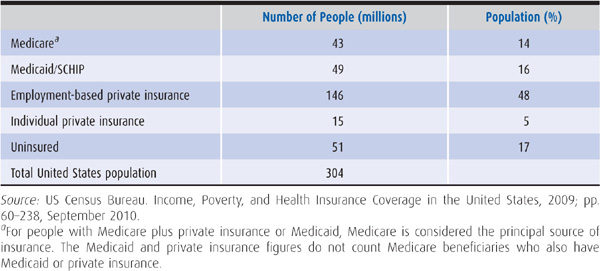

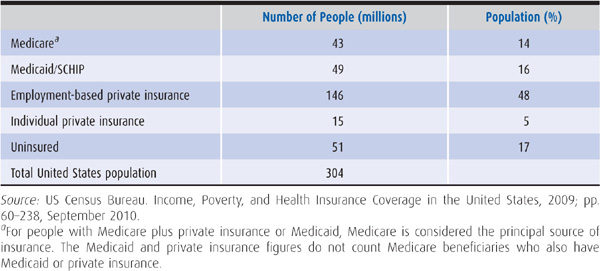

Health insurance coverage, whether public or private, is a key factor in making health care accessible. In 1980, 25 million people were uninsured, but by 2009 the number had increased to 51 million (Table 3–1 and Figure 3–1) (US Census Bureau, 2010). The particular pattern of uninsurance is related to the employment-based nature of health care financing. Most people, like Ernestine Newsome, obtain health insurance when employers voluntarily decide to offer group coverage to employees and their families and their employers help pay for the costs of health insurance. People whose employers choose not to provide health insurance, are self-employed, or are unemployed are left to fend for themselves outside of the employer-sponsored group health insurance market, with the result that many are uninsured. Often people without employment-based insurance are not eligible for public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, and are unable to purchase individual private coverage because they cannot afford the premiums.

Table 3–1. Estimated principal source of health insurance, 2009

Figure 3–1. Number of uninsured persons in the United States, 1980 to 2009 (US Census Bureau, 2010).

Between the 1930s and mid-1970s, because of the growth of private health insurance and the 1965 passage of Medicare and Medicaid, the number of uninsured persons declined steadily, but since 1976, the number has been growing. The single most important factor explaining the growing number of uninsured is a 25-year trend of decreasing private insurance coverage in the United States. Virtually all people aged 65 and older are covered by Medicare, and the number of people enrolled in Medicaid has increased. However, a dwindling proportion of children and working age adults are covered by private insurance, exposing the limitations of the employment-linked system of private insurance in the United States. If the 2010 health care reform law, the Accountable Care Act, is fully implemented, the number of uninsured people is expected to drop from 51 million to 22 million (Buettgens et al, 2010).

Joe Fortuno dropped out of high school and went to work for Car Doctor auto body shop in 2003. His employer paid the full cost of health insurance for Joe and his family. Joe’s younger cousin Pete Luckless got a job working at an auto mechanic shop in 2005. The company did not offer health insurance benefits. In 2008, Car Doctor, after experiencing a doubling of health insurance premium rates over the prior few years, began requiring that its employees pay $150 per month for the employer-sponsored health plan. Joe could not afford the monthly payments and lost his health insurance.

Why has private health insurance coverage decreased over the past decades, creating the uninsurance crisis? There are several explanations:

1. The skyrocketing cost of health insurance has made coverage unaffordable for many businesses and individuals. From 2000 to 2010, employer-sponsored health insurance premiums rose by 114%. In 2010, the average annual cost of health insurance, including employer and employee contributions, was $5049 for individuals and $13,770 for families (Claxton et al, 2010). Some employers responded to rising health insurance costs by dropping insurance policies for their workers. Many employers have shifted more of the cost of health insurance premiums and health services onto their employees, resulting in employees dropping health coverage because of unaffordability. On average, employee contributions represent 19% of the premium for individual employee coverage and 30% for family coverage, though some employees have to pay more than half of the premium for family coverage (Claxton et al, 2010). Low-income workers are hit especially hard by the combination of rising insurance costs and declining employer subsidies.

Jean Irons worked for Bethlehem Steel as a clerk and her fringe benefits included health insurance. Bethlehem Steel was bought by a global corporation and her plant moved to another country. She found a job as a food service worker in a small restaurant. Her pay decreased by 35%, and the restaurant did not provide health insurance.

2. During the past few decades, the economy in the United States has undergone a major transition. The number of highly paid, largely unionized, full-time manufacturing workers with employer-sponsored health insurance has declined, and the workforce has shifted toward more low-wage, increasingly part-time, nonunionized service, and clerical workers whose employers are less likely to provide insurance (Renner and Navarro, 1989). Between 1980 and 2006, the number of workers in the manufacturing sector decreased by 30% while the number working in the service sector increased by 75%. From 1957 to 2000, the percentage of workers with part-time jobs—generally without health benefits—increased from 12% to 21%.

These two factors—increasing health care costs and a changing labor force—eroded private insurance coverage. One countervailing trend has been a major expansion of public insurance coverage through the Medicaid and State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) programs. Without these changes, many more millions of Americans would currently be uninsured.

Sally Lewis worked as a receptionist in a physician’s office. She received health insurance through her husband, who was a construction worker. They got divorced, she lost her health insurance, and her physician employer told her he could not provide her with health insurance because of the cost.

3. The link of private insurance with employment inevitably produces interruptions in coverage because of the unstable nature of employment. People who are laid off from their jobs or who leave jobs because of illness may also lose their insurance. Family members insured through the workplace of a spouse may lose their insurance in cases of divorce, job loss, or death of the working family member. People who leave their employment may be eligible to pay for continued coverage under their group plan for 18 months, as stipulated in the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA), with the requirement that they pay the full cost of the premium; however, many people cannot afford the premiums, which may exceed $1000 per month for a family.

The often transient nature of employment-linked insurance is compounded by difficulties in maintaining eligibility for Medicaid. Small increases in family income can mean that families no longer qualify for Medicaid. The net result is that millions of people cycle in and out of the ranks of the uninsured every month. A total of 87 million people, 29% of the entire US population, went without health insurance for all or part of the 2-year period 2007–2008 (Families USA, 2009). Health insurance may be a fleeting benefit.

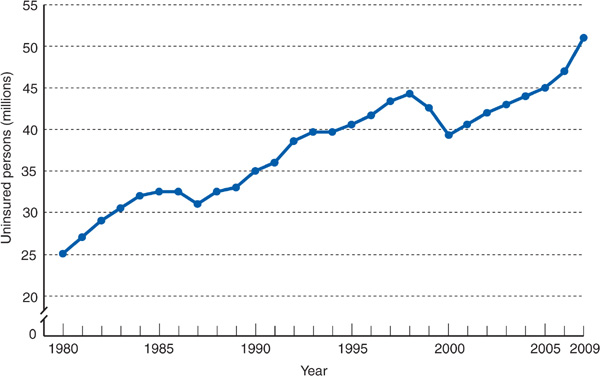

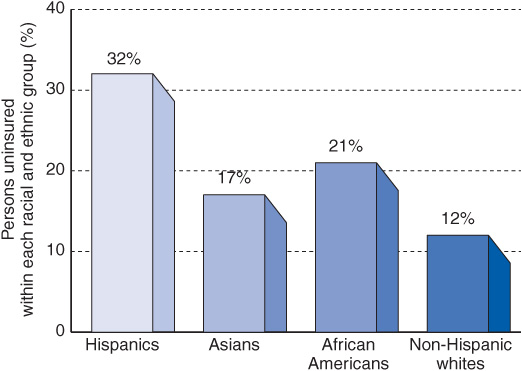

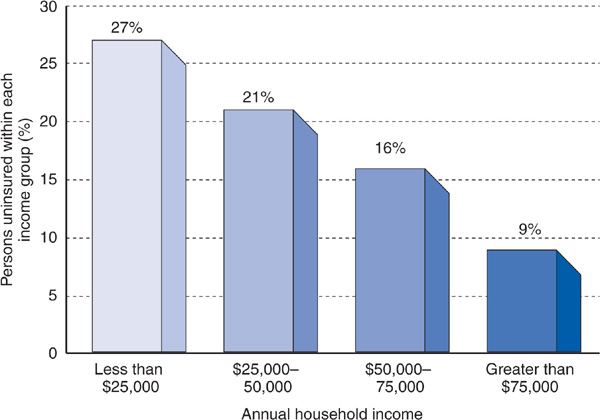

In 2009, 12% of non-Hispanic whites were uninsured, compared with 21% of African Americans, 17% of Asians, and 32% of Latinos (Figure 3–2). Twenty-seven percent of individuals with annual household incomes less than $25,000 were uninsured, compared with 9% of individuals with household incomes of $75,000 or more (Figure 3–3) (US Census Bureau, 2010).

Figure 3–2. Percentage of population lacking health insurance by race and ethnicity in 2009 (US Census Bureau, 2010).

Figure 3–3. Lack of insurance by income in 2009 (US Census Bureau, 2010).

Morris works for a corner grocery store that employs five people. Morris once asked the owner whether the employees could receive health insurance through their work, but the owner said it was too expensive. Morris, his wife, and their three kids are uninsured.

Norris, a shipyard worker, was laid off 3 years ago, and at age 60 is unable to get another job. He lives on county general assistance of $400 per month, but is ineligible for Medicaid because he is not a parent, not older than 65, and not disabled. He is uninsured.

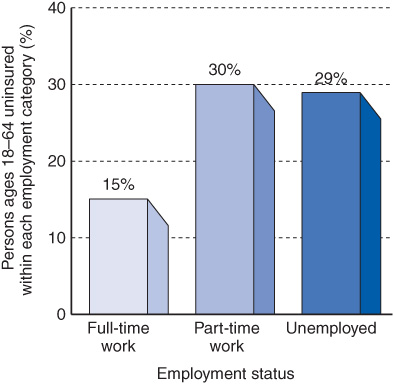

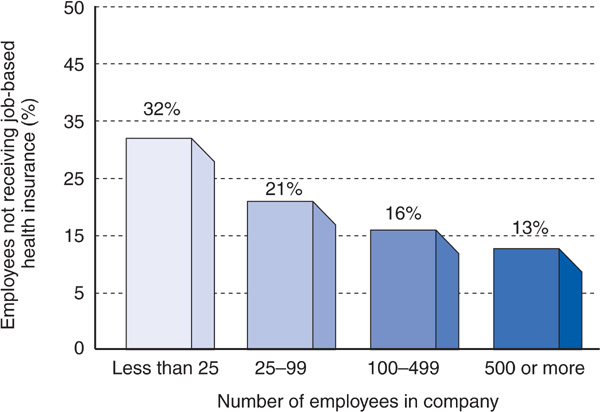

The uninsured can be divided into two major categories: the employed uninsured (Morris) and the unemployed uninsured (Norris). Seventy-five percent of the uninsured are employed or the spouses and children of those who work. Most of the jobs held by the employed uninsured are low paying, in small firms, and may be part time (Figures 3–4 and 3–5). Twenty-five percent of the uninsured are unemployed, often with incomes below the poverty line, but like Norris are ineligible for Medicaid.

Figure 3–4. Lack of insurance by employment status in 2009 (US Census Bureau, 2010).

Figure 3–5. Lack of job-based insurance by size of employer in 2007 (Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Insurance Coverage in America, 2008, www.kff.org).

Two US senators are debating the issue of access to health care. One decries the stigma of uninsurance and claims that people without insurance receive less care and suffer worse health than those with insurance. The other disagrees, claiming that hospitals and physicians deliver large amounts of charity care, which allows uninsured people to receive the services they need.

To resolve this debate, the US Congress Office of Technology Assessment (1992) conducted a comprehensive review to determine whether health insurance makes a difference in the use of health care and in health outcomes. The findings, corroborated by the Institute of Medicine (2002), proved that people lacking health insurance receive less care and have worse health outcomes.

Percy, a child whose parents were both employed but not insured, was refused admission by a private hospital for treatment of an abscess. Outpatient treatment failed, and his mother attempted to admit Percy to other area hospitals, which also refused care. Finally an attorney arranged for the original hospital to admit the child; the parents then owed the hospital $6000.

Access to health care is most simply measured by the number of times a person uses health care services. Commonly used data are numbers of physician visits, hospital days, and preventive services received. In addition, access can be quantified by surveys in which respondents report whether or not they failed to seek care or delayed care when they felt they needed it. In 2009, 56% of uninsured adults, compared with 10% of those with insurance, had no usual source of care, 32%, compared with 8% of those with insurance, postponed seeking care due to cost, and 26%, compared with 4% for those with insurance, went without needed care due to cost (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010a).

Dan Sugarman noticed that he was urinating a lot and feeling weak. His friend told him that he had diabetes and needed medical care, but lacking health insurance, Mr. Sugarman was afraid of the cost. Eight days later, his friend found him in a coma. He was hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis.

Penny Evans worked in a Nevada casino. She was uninsured and ignored a growing mole on her chest. After many months of delay, she saw a dermatologist and was diagnosed with malignant melanoma, which had metastasized. She died 2 years later at the age of 44.

Leo Morelli, a hypertensive patient, was doing well until his company relocated to Mexico and he lost his job. Lacking both paycheck and health insurance, he became unable to afford his blood pressure medications. Six months later, he collapsed with a stroke.

The uninsured suffer worse health outcomes than those with insurance. Compared with insured persons, the uninsured like Mr. Sugarman have more avoidable hospitalizations; like both Mr. Sugarman and Ms. Evans, they tend to be diagnosed at later stages of life-threatening illnesses, and they are on average more seriously ill when hospitalized (American College of Physicians, 2000). Higher rates of hypertension and cervical cancer and lower survival rates for breast cancer among the uninsured, compared with those with insurance, are associated with less frequent blood pressure screenings, Pap smears, and clinical breast examinations (Ayanian et al, 2000). People without insurance have greater rates of uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, and elevated cholesterol than those with insurance (Wilper et al, 2009). Most significantly, people who lack health insurance suffer a higher overall mortality rate than those with insurance. After adjusting for age, sex, education, poorer initial health status, and smoking, it was found that lack of insurance alone increased the risk of dying by 25% (Franks et al, 1993). The Institute of Medicine estimated that lack of health insurance accounts for 18,000 deaths annually in the United States (Institute of Medicine, 2004).

Medicaid, the federal and state public insurance plan, has made great strides in improving access to care for two-thirds of people with incomes below the federal poverty level, but Medicaid has its limitations.

Concepcion Ortiz lived in a town of 25,000 persons. When she became pregnant, her sister told her that she was eligible for Medicaid, which she obtained. She called each obstetrician in town and none would take Medicaid patients. When she reached her sixth month, she became desperate.

For those people with Medicaid coverage, access to care is by no means guaranteed. Medicaid pays physicians far less than does Medicare or private insurance with the result that many physicians do not accept Medicaid patients.

As a rule, people with Medicaid have a level of access to medical care that is intermediate between those without insurance and those with private insurance. Compared with uninsured people, those with Medicaid are more likely to have a regular source of medical care and are less likely to report delays in receiving care. But these access measures for Medicaid recipients are not as good as for people with private insurance (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010a).

Health outcomes for Medicaid recipients lag behind those for privately insured people. Compared with privately insured people, Medicaid recipients have lower rates of immunizations, screening for breast and cervical cancer, hypertension and diabetes control, and timeliness of prenatal care. (Landon et al, 2007). Medicaid patients with cancer have their disease detected at significantly later stages than privately insured patients, with the delays in diagnosis comparable for uninsured and Medicaid patients (Halpern et al, 2007). Persons with Medicaid are sometimes relegated, with the uninsured, to the lowest tier of the health care system.

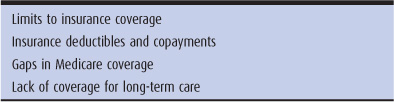

Health insurance does not guarantee financial access to care. Many people are underinsured; that is, their health insurance coverage has limitations that restrict access to needed services (Table 3–2). An estimated 20% of insured Americans between the ages of 19 and 64 were underinsured in 2007, up from 12% in 2003 (Gabel et al, 2009).

Table 3–2. Categories of underinsurance

In 2007, 71% of privately insured people with low incomes and substantial medical expenditures were underinsured. This number is rising as health care costs rise and insurance coverage becomes less comprehensive (Gabel et al, 2009). In 2007, 62% of bankruptcies in the United States were caused by inability to pay medical bills; 75% of these individuals had health insurance at the onset of their illness (Himmelstein et al, 2009).

Eva Stefanski works as a legal secretary and has a Blue Cross high-deductible health plan policy with a $2500 deductible. Last year, she failed to show up for her mammogram appointment because she did not have $150 to pay for the test. This year, she also decides to forego making an appointment for her periodic pap test.

For people with low or moderate incomes, insurance deductibles and copayments may represent a substantial financial problem. From 2006 to 2010, the percent of people with employer-sponsored insurance having a deductible of $1000 or more for single (not family) coverage grew from 10% to 27%. In 2010, 13% of insured employees (up from 4% in 2006) had high-deductible insurance plans, with families paying an average deductible of $3500 plus the employee premium contribution and copayments (Claxton et al, 2010).

Corazon Estacio suffers from angina, congestive heart failure, and high blood pressure, in addition to diabetes. She takes 17 pills per day: four each of glyburide and metformin, three isosor-bide, two carvedilol and two furosemide, and one each of benazepril and aspirin. Because of the deductibles and the “doughnut hole” in her Medicare Part D plan, her yearly medication bill comes to $3840.

Ferdinand Foote was covered by Medicare and had no Medigap, Medicare Advantage, or Medicaid coverage. He was hospitalized for peripheral vascular disease caused by diabetes and a non-healing infected foot ulcer. He spent 4 days in the acute hospital and 1 month in the skilled nursing facility and made weekly physician visits following his discharge. The costs of illness not covered by Medicare included a $1132 deductible for acute hospital care, a $141.50 per day copayment for days 21 to 30 of the skilled nursing facility stay, a $162 physician deductible, and a 20% ($12) physician copayment per visit for 12 visits. The total came to $2853 not including the cost of uncovered outpatient medications.

Medicare paid for only 48% of the average beneficiary’s health care expenses in 2006 (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010b). For the 5% of beneficiaries in poorest health, uncovered costs in 2004 averaged $7646, up 48% from 1992 (Riley, 2008). As discussed in Chapter 2, Medicare Part D requires beneficiaries to continue shouldering large out-of-pocket expenses for their medications, a situation that is expected to improve with the Accountable Care Act of 2010.

Victoria and Gus Pappas had $80,000 in the bank when Gus had a stroke. After his hospitalization, he was still paralyzed on the right side and unable to speak or swallow. After 18 months in the nursing home, most of the $80,000 was gone. At that point, Medicaid picked up the nursing home costs.

Medicare paid only 20% of the elderly’s nursing home bills in 2009, and private insurance policies picked up only an additional 8% (see Chapter 12). Many elderly families spend their life savings on long-term care, qualifying for Medicaid only after becoming impoverished.

Does underinsurance represent a serious barrier to the receipt of medical care? The famous Rand Health Insurance Experiment compared nonelderly individuals who had health insurance plans with no out-of-pocket costs and those who had plans with varying amounts of patient cost sharing (deductibles or copayments). The study found that cost sharing reduces the rate of ambulatory care use, especially among the poor, and that patients with cost-sharing plans demonstrate a reduction in both appropriate and inappropriate medical visits. For low-income adults, the cost-sharing groups received Pap smears 65% as often as the free-care group. Hypertensive adults in the cost-sharing groups had higher diastolic pressures, and children had higher rates of anemia and lower rates of immunization (Brook et al, 1983; Lohr et al, 1986; Lurie et al, 1987).

In 2003, underinsured adults aged 19 to 64 with health problems were much more likely than well-insured adults to skip recommended tests or follow-up, forego seeing a physician when they felt sick, and fail to fill a prescription on account of cost (Schoen et al, 2005). In 2006, 20% of Medicare beneficiaries with Part D coverage did not fill, or delayed filling, a prescription due to inability to pay the uncovered costs (Neuman et al, 2007). In summary, lack of comprehensive insurance reduces access to health care services and may contribute to poorer health outcomes.

Nonfinancial barriers to health care include inability to access care when needed, language, literacy, and cultural differences between patients and health caregivers, and factors of gender and race. Excellent discussions of these issues can be found in the book “Medical Management of Vulnerable and Underserved Patients” (King and Wheeler, 2007).

Medical practices often fail to provide their patients with access at the time when the patient needs care. This problem has worsened with the growing shortage of primary care practitioners. In 2008, 28% of Medicare beneficiaries without a primary care physician reported difficulty finding such a physician, a 17% increase from 2006. Thirty-one percent of privately insured patients had an unwanted delay in obtaining an appointment for routine care in 2008. In 2006, only 27% of adults with a usual source of care could easily contact their physician by phone, obtain care or advice after hours, and experience timely office visits. After Massachusetts passed its health insurance expansion in 2006, demand for primary care increased without an increase in supply, resulting in the average wait time to see a primary care internist increasing from 17 days in 2005 to 31 days in 2008. Fewer primary care physicians are accepting Medicaid patients, and inappropriate emergency department visits are growing, especially for Medicaid patients, due to inability to access timely primary care (Bodenheimer and Pham, 2010).

Olga Madden is angry. Her male physician had not listened. He told her that her incontinence was from too many childbirths and that she would have to live with it. She had questions about the hormones he was prescribing, but he always seemed too busy, so she never asked. Ms. Madden calls her HMO and gets the names of two female physicians, a female physician assistant, and a nurse practitioner. She calls them. Their receptionists tell her that none of them is accepting new patients; they are all too busy.

Access problems for women often begin with finding a physician who communicates effectively. Women are 50% more likely than men to report leaving a physician because of dissatisfaction with their care, and they are more than twice as likely to report that their physician “talked down” to them or told them their problems were “all in their head” (Leiman et al, 1997). Female physicians have a more patient-centered style of communicating and spend more time with their patients than do male physicians (Roter and Hall, 2004). In a study of patients with insurance coverage for Pap smears and mammo-grams, the patients of female physicians were almost twice as likely to receive a Pap smear and 1.4 times as likely to have a mammogram than the patients of male physicians (Lurie et al, 1993).

Physicians are less likely to counsel women than men about cardiac prevention—diet, exercise, and weight reduction. After having a heart attack, women are less likely than men to receive recommended diagnostic tests and are less likely to be prescribed recommended aspirin and beta-blockers (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005).

Because women are more likely than men to have a chronic condition, women use more chronic medications and are more likely than men not to fill a prescription because of cost. Because more women than men are Medicaid recipients, they are more likely to be turned away from physicians who do not accept Medicaid. Fewer than one-third of women of reproductive age have received counseling about emergency contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, or domestic violence (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005b).

For those women who wish to terminate a pregnancy, access to abortions is limited in many areas of the country. In 2009, 87% of US counties had no identifiable abortion provider. While women have reduced access to certain kinds of care, an equally serious problem may be instances of inappropriate care. A study conducted in a managed-care medical group in California found that 70% of hysterectomies were inappropriate (Broder et al, 2000).

Jose is suffering. The pain from his fractured femur is excruciating, and the emergency department physician has given him no pain medication. In the next room, Joe is asleep. He has received 10 mg of morphine for his femur fracture.

At a California emergency department, 55% of Latino patients with extremity fractures received no pain medication compared with 26% of non-Latino whites. This marked difference in treatment was attributable not to insurance status but to ethnicity (Todd et al, 1993). African American patients similarly receive poorer pain control than whites (Todd et al, 2000).

Because a far higher proportion of minorities than whites is uninsured, has Medicaid coverage, or is poor, access problems are amplified for these groups. African Americans and Latinos in the United States are less likely to have a regular source of care or to have had a physician visit in the past year (King and Wheeler, 2007). Racial and ethnic differences in access to care are not always a matter of differences in financial resources and insurance coverage. Studies have shown that African Americans and Latinos receive fewer services even when compared with non-Hispanic whites who have the same level of health insurance and income (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2009).

Studies have also detected such disparities in quality of care. Looking at 38 measures of quality for such conditions as diabetes, asthma, HIV/AIDS, cardiac care, and cancer, African Americans receive poorer quality of care than whites for 66% of these quality measures; American Indians and Alaska Natives and Latinos also have lower quality indicators (King and Wheeler, 2007).

Neighborhoods that have high proportions of African American or Latino residents have far fewer physicians practicing in these communities. African American and Latino primary care physicians are more likely than white physicians to locate their practices in underserved communities (Komaromy et al, 1996).

What explains these disparities in access to care across racial and ethnic groups that are not fully accounted for by differences in insurance coverage and socioeconomic status? Several hypotheses have been proposed. Cultural differences may exist in patients’ beliefs about the value of medical care and attitudes toward seeking treatment for their symptoms. However, differences in patient preferences do not account for substantial amounts of the racial variations seen in cardiac surgery rates (Mayberry et al, 2000). A related factor may be ineffective communication between patients and caregivers of differing races, cultures, and languages. African Americans are more likely than whites to report that their physicians did not properly explain their illness and its treatment (LaVeist et al, 2000). Access barriers related to communication problems may be particularly acute for the subset of Latino patients for whom Spanish is the primary language. However, language issues do not fully account for access barriers faced by Latinos. In the study of emergency department pain medication cited previously, even Latinos who spoke English as their primary language were much less likely than non-Latino whites to receive pain medication.

Because many of these hypotheses do not satisfactorily explain the observed racial disparities in access to care, an important consideration is whether racism may also contribute to these patterns (King and Wheeler, 2007). Medicine in the United States has not escaped the nation’s legacy of institutionalized racism toward many minority groups. Many hospitals, including institutions in the North, were for much of the twentieth century either completely segregated or had segregated wards, with inferior facilities and services available to nonwhites. Explicit segregation policies persisted in many hospitals until a few decades ago. Racial barriers to entry into the medical profession gave rise to the establishment of black medical schools such as the Howard, Morehouse, and Meharry schools of medicine. Although such overt racism is a diminishing feature of medicine in the United States, more insidious and often unconscious forms of discrimination may continue to color the interactions between patients and their caregivers and influence access to care for minorities (Van Ryn, 2002).

Access to health care does not by itself guarantee good health. A complex array of factors, only one of which is health care, determines whether a person is healthy or not.

Ace Banks is 48, an executive vice president, with four grandparents who lived past 90 years of age and parents alive and well in their late 70s. Mr. Banks went to an Ivy League college where he was a star athlete. He has never seen a physician except for a sprained ankle.

Keith Cole is a coal miner who at age 48 developed pneumonia. He had excellent health insurance through his union and went to see the leading pulmonologist in the state. He was hospitalized but became less and less able to breathe because the pneumonia was severely complicated by black lung disease, which he contracted through his job. He received high-quality care in the intensive care unit at a fully insured cost of $65,000, but he died.

Bill Downes, an African American man, knew that his father was killed by high blood pressure and his mother died of diabetes. Mr. Downes spent his childhood in poverty living with eight children at his grandmother’s house. He had little to eat except what was provided at the school lunch program, a diet heavily laden with cheese and butter. To support the family, he left school at age 15 and got a job. At age 24, he was diagnosed with high blood pressure and diabetes. He did not smoke and was meticulous in following the diet prescribed by his physician. He had private health insurance through his job as a security guard and was cared for by a professor of medicine at the medical school. In spite of excellent medical care, his glucose and cholesterol levels and blood pressure were difficult to control, and he developed retinopathy, kidney failure, and coronary heart disease. At age 48, he collapsed at work and died of a heart attack.

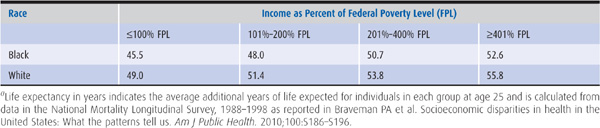

The gap between the rich and the poor has widened markedly in the United States. Between 1952 and 2005, the proportion of pretax income reported by the wealthiest decile of the population increased from 31% to 44%; the share of income for the richest 1% doubled from 8% in 1980 to 17% in 2005. At the same time, income is decreasing for the great majority of households (Woolf, 2007). As the stories of Ace Banks, Keith Cole, and Bill Downes suggest, the health of an individual or a population is influenced less by medical care than by broad socioeconomic factors such as income and education (Braveman et al, 2010). People in the United States with incomes above four times the poverty level live on average 7 years longer than those with incomes below the poverty level (Table 3–3). The mortality rate for heart disease among laborers is more than twice the rate for managers and professionals. The incidence of cancer increases as family income decreases, and survival rates are lower for low-income cancer patients. Higher infant mortality rates are linked to low income and low educational level. Not only does the income level of individuals affect their health and life expectancy, the way in which income is distributed within communities also appears to influence the overall health of the population. In the United States, overall mortality rates are higher in states that have a more unequal distribution of income, with greater concentration of wealth in upper income groups (Lochner et al, 2001). Some social scientists have concluded that the toxic health effects of social inequality in developed nations result from the psychosocial stresses of social hierarchies and social oppression, not simply from material deprivation (Kawachi and Kennedy, 1999).

Table 3–3. Income, race, and life expectancy in years (at age 25)a

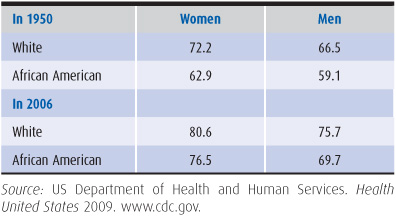

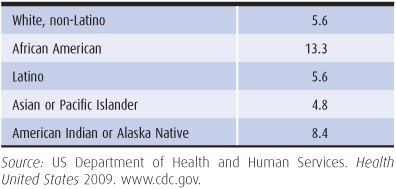

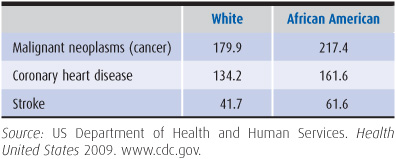

African Americans experience dramatically worse health than white Americans. Life expectancy is lower for African Americans than for other racial and ethnic groups in the United States (Table 3–4). Infant mortality rates among African Americans are more than double those for whites (Table 3–5), and the relative disparity in infant mortality has widened during the past decade. Mortality rates for African Americans exceed those for whites for 7 of the 10 leading causes of death in the United States, including the most common killers in the US population—heart disease, strokes, and cancer (Table 3–6) (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). African American men younger than 45 years have 10 times the likelihood of dying of hypertension than white men in the same age group. Although the incidence of breast cancer is lower in African American women than in white women, in African American women this disease is diagnosed at a more advanced stage of illness, and thus they are more likely to die of breast cancer (Institute of Medicine, 2003; Halpern et al, 2007).

Table 3–4. Life expectancy in years

Table 3–5. Infant mortality, 2006 (per 1000 live births)

Table 3–6. Age-adjusted death rates per 100,000 population, 2006

Native Americans are another ethnic group with far poorer health than that of whites. Native Americans younger than 45 years have far higher death rates than whites of comparable age, and the Native American infant mortality rate is 50% higher than the rate of whites (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

Latinos and Asians and Pacific Islanders are minority groups characterized by great diversity. Health status varies widely between Cuban Americans, who tend to be more affluent, and poor Mexican American migrant farm workers, as well as between Japanese families, who are more likely to be middle class, and Laotians, who are often indigent. Compared with whites, Latinos have markedly higher death rates for diabetes and the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Overall, Latinos have lower age-adjusted mortality rates than whites because of less cardiovascular disease and cancer. Asians in the United States have lower death rates than whites for all age groups (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

Some of the differences in mortality rates of African Americans and Native Americans compared with whites are related to the higher rates of poverty among these minority groups. In 2009, the white poverty rate was 12% compared with 26% for African Americans, and 25% for Latinos (US Census Bureau, 2010). However, even compared with whites in the same income class, African Americans as a group have inferior health status. Although mortality rates decline with rising income among both African Americans and whites, at any given income level, the mortality rate for African Americans is consistently higher than the rate for whites (Table 3–3). Thus, social factors and stresses related to race itself seem to contribute to the relatively poorer health of African Americans. The inferior health outcomes among African Americans, such as higher mortality rates for heart disease, cancer, and stroke, are in part explained by the lower rate of access to health services among this group.

If lower income is associated with poorer health, and if Latinos tend to be poorer than non-Latino whites in the United States, then why do Latinos have overall lower mortality rates than non-Latino whites? This is possibly related to the fact that many Latinos are immigrants, and foreign-born people often have lower mortality rates than people born in the United States at the same level of income (Abraido-Lanza et al, 1999; Goel et al, 2004). This phenomenon is often referred to as the “healthy immigrant” effect. If this is the case, mortality rates for Latinos may rise as a higher proportion of their population is born in the United States.

Health outcomes are determined by multiple factors. Socioeconomic status appears to be the dominant influence on health status; yet medical care and public health interventions are also extremely important (King and Wheeler, 2007). The advent of the polio vaccine markedly reduced the number of paralytic polio cases. From 1970 to 2004, age-adjusted death rates from stroke decreased by more than 100%—a successful result of hypertension diagnosis and treatment. Early prenatal care can prevent low-birth-weight and infant deaths. Irradiation and chemotherapy have transformed the prognosis of some cancers (eg, Hodgkin disease) from a certain fatal outcome toward complete cure. A 1980 study of mortality rates in 400 counties in the United States found that after controlling for income, education, cigarette consumption, and prevalence of disability, a 10% increase in per capita medical care expenditures was associated with a reduced average mortality rate of 1.57% (Roemer, 1991). Moreover, the health care system provides patients with chronic disease welcome relief from pain and suffering and helps them to cope with their illnesses. Access to health care does not guarantee good health, but without such access health is certain to suffer.

Abraido-Lanza AF et al. The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypothesis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1543.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Women’s Health Care in the United States. May 2005. www.ahrq.gov.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2009. www.ahrq.gov.

Ayanian JZ et al. Unmet needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284:2061.

Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: Current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010:29:799.

Braveman PA et al. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:S186–S196.

Broder MS et al. The appropriateness of recommendations for hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:199.

Brook RH et al. Does free care improve adults’ health? N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1426.

Buettgens M et al. Why the Individual Mandate Matters. Urban Institute Web Site. December 2010. www.urban.org.

Claxton G et al. Health benefits in 2010: Premiums rise modestly, workers pay more toward coverage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1942.

Families USA. Americans at Risk. One in Three Uninsured. March 2009. www.familiesusa.org.

Franks P et al. Health insurance and mortality. JAMA. 1993;270:737.

Gabel JR et al. Trends in underinsurance and the affordability of employer coverage, 2004–2007. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009; 28:w595.

Goel MS et al. Obesity among US immigrant subgroups by duration of residence. JAMA. 2004;292:2860.

Halpern MT et al. Insurance status and stage of cancer at diagnosis among women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:231.

Himmelstein DU et al. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007. Am J Med. 2009;122:741.

Institute of Medicine. Care Without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002.

Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

Institute of Medicine. Insuring America’s Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

Kaiser Family Foundation. The Uninsured and the Difference Health Insurance Makes. September 2010a. www.kff.org.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare Spending and Financing. 2010b. www.kff.org.

Kaiser Family Foundation: Women and Health Care. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; July 2005. www.kff.org.

Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Income inequality and health: Pathways and mechanisms. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:215.

King TE, Wheeler MB. Medical Management of Vulnerable and Underserved Patients. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

Komaromy M et al. The role of Black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1305.

Landon BE et al. Quality of care in Medicaid managed care and commercial health plans. JAMA. 2007;298:1674.

LaVeist TA et al. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146.

Leiman JM et al. Selected Facts on U.S. Women’s Health: A Chart Book. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 1997.

Lochner K et al. State-level income inequality and individual mortality risk: A prospective, multilevel study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:385.

Lohr KN et al. Use of medical care in the Rand Health Insurance Experiment. Med Care. 1986;24(Suppl):S1.

Lurie N et al. Preventive care: Do we practice what we preach? Am J Public Health. 1987;77:801.

Lurie N et al. Preventive care for women: Does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;329:478.

Mayberry RM et al. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):108.

Neuman P et al. Medicare prescription drug benefit progress report. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:w630.

Renner C, Navarro V. Why is our population of uninsured and underinsured persons growing? The consequences of the “deindustrialization” of the United States. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19:433.

Riley GF. Trends in out-of-pocket healthcare costs among older community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:692.

Roemer MI. National Health Systems of the World. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991.

Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:497.

Schoen et al. Insured but not protected: How many adults are underinsured? Health Affairs Web Exclusive. June 14, 2005:w5–289. http://content.healthaffairs.org. Accessed November 11, 2011.

Todd KH et al. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:11.

Todd KH et al. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA. 1993;269: 1537.

US Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States, 2009; pp. 60–238, September, 2010.

US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Does Health Insurance Make a Difference? OTA-BP-H-99. US Government Printing Office; 1992.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Health United States 2009. www.cdc.gov.

Van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002;40(Suppl):I-140.

Wilper et al. Hypertension, diabetes, and elevated cholesterol among insured and uninsured U.S. adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:1151.

Woolf SH. Future health consequences of the current decline in US household income. JAMA. 2007;298:1931.