I

HOW THE YOUTH KILHUCH CAME TO KING ARTHUR’S COURT

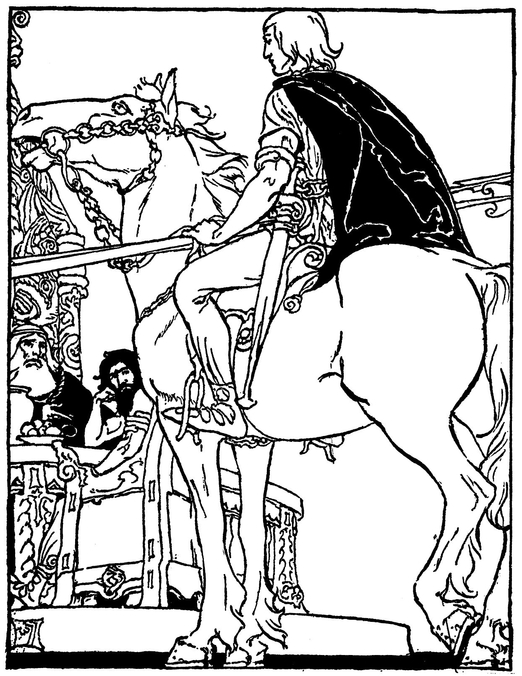

Thus the youth rode to the Court of King Arthur: the horse that was under him was of four winters old, firm of limb, with head of dappled grey, with shell-formed hoofs, having a bridle of linked gold on its head, and on its back a saddle of gold. In the youth’s hands were two spears of silver, sharp and well-tempered, of an edge to wound the wind, and swifter than the fall of a dew-drop from the blade of reed-grass upon the earth when the dew of June is at its heaviest. A gold-hilted sword was upon his thigh, the blade of which was of gold, bearing a cross of inlaid gold of the hue of the lightning of heaven, and his warhorn was of ivory. Before him were two brindled, white-breasted grey-hounds, having strong collars of rubies about their necks. And the hound that was on his left side bounded across to the right side, and the one on his right to his left, and like two sea-swallows they sported around him. His horse, as it coursed along, cast up four sods with its four hoofs, like four swallows in the air, about his head, now above, now below. About him was a four-cornered cloth of purple, and an apple of gold was at each corner, and every one of the apples was of the value of an hundred kine. And there was precious gold of the value of three hundred kine upon his shoes, and upon his stirrups, from his knee to the tip of his toe. And the blade of grass bent not beneath him, so light was his courser’s tread as he journeyed towards the gate of King Arthur’s palace.

When he came before the palace, the youth called out, “Open the gate.” “I will not open it,” said the porter. “Wherefore not?” asked the youth. “The knife is in the meat, and the drink is in the horn, and there is revelry in Arthur’s hall, and none may enter therein except the son of a King of a privileged country, or a craftsman bringing here his craft. Stay thou outside. There will be refreshment for thy hounds and for thy horse, and for thee there will be collops of meat cooked and peppered, and luscious wine, and mirthful songs. A lady shall smooth thy couch for thee and lull thee with her singing; and early in the morning, when the gate is opened for the multitude that came hither to-day, for thee it shall be opened first, and thou mayest sit in the place that thou shalt choose in Arthur’s hall.” Said the youth, “That I will not do. If thou openest the gate for me, it is well. But if thou dost not open it, I will set up three shouts at this very gate, and these shouts will be deadly to all.” “What clamour soever thou mayest make,” said the porter, “against the law of King Arthur’s palace thou shalt not enter until I go first and speak with the King.”

So the porter went into the hall. The King said to him when he came near, “Hast thou news from the gate?” The porter said, “Half my life is past, and half of thine. I have seen with thee supreme sovereigns, but never did I behold one of equal dignity with him who is now at thy gate.” Then said King Arthur to him, “If walking thou didst enter, return thou running. It is unbecoming to keep such a one as thou sayest he is outside in wind and rain.” Then said the knight Kai who was in Arthur’s hall at the time, “By the hand of my friend, if thou wouldst follow my counsel, thou wouldst not break through the laws of thy court because of him.” “Not so, blessed Kai,” said Arthur. “The greater our courtesy, the greater will be our renown, and our fame, and our glory.” And by this time the porter was back at the gate.

He opened the gate before the youth who had been waiting before it. Now, although all comers dismounted upon the horse-block that was at the gate, yet did he not dismount, but he rode right in on his horse. “Greeting be unto thee, sovereign ruler of the Island,” he said, “and be this greeting no less unto the lowest than unto the highest, and be it equally unto thy guests, and thy warriors, and thy chieftains—let all partake of it equally with thyself. And complete be thy favour, and thy fame, and thy glory throughout all this Island.” “Greeting be unto thee also,” said King Arthur. “Sit thou between two of my warriors, and thou shalt have minstrels before thee, and thou shalt enjoy the privileges of a King born to a throne, as long as thou remainest here.” Said the youth, “I came not to consume meat and drink; but if I obtain the boon that I have come seeking, I will requite it thee.” Then said Arthur: “Since thou wilt not remain here, Chieftain, thou shalt receive the boon whatsoever thy tongue may name, as far as the wind dries, and the rain moistens, and the sun revolves, and the sea encircles, and the earth extends; any boon thy tongue may name save only my ship and my mantle, my sword and my lance, my shield and my dagger, and Gwenhuivar, my wife. By the truth of Heaven, thou shalt have it cheerfully, name what thou wilt. For my heart warms unto thee, and I know thou art of my blood.” “Of thy blood I am indeed,” said the youth, “for my mother was thy mother’s sister, Prince Anlod’s daughter.” Thereupon he told the King of his birth and his upbringing.

“Greeting be unto thee, sovereign ruler of the Island.”

Kilhuch he was called, and he was given that name because he was born in a swine’s pen. Before he was born, his mother became wild, and she wandered about, without habitation. Then she came to a mountain where ther was a swineherd, keeping a herd of swine; there she stayed, and in the swine’s pen her son was born. The swineherd took the boy, and brought him to the palace of his father, and there he was christened. Afterwards he was sent to be reared in another place.

His mother died soon afterwards. When she knew she was going to die, she sent for the Prince, her husband, and she said to him, “I charge thee not to take a wife until thou seest a briar with two blossoms growing out of my grave.” And she asked him to have the grave tended, day by day, and year by year, so that nothing might grow on it. This he promised her, and, soon after, she died.

For seven years the Prince sent an attendant every morning to dress her grave and to see if anything were growing upon it. But at the end of the seventh year he neglected to do that which he had promised to his wife. Then one day he went hunting. He passed by the place of burial and he saw a briar growing out of his wife’s grave. He knew then that the time had come for him to seek another wife. He sought for one, and he married again, and brought another lady into his palace.

A day came when the lady he married went walking abroad. She came to the house of an old crone, and going within she said to the woman, “Old woman, tell me that which I shall ask thee. Where are the children of the man who has married me?” “Children he has none,” said the crone. “Woe is me,” said the lady, “that I have come to one who is childless.” “Children he has none,” said the crone, “but a child he has. Thou needst not lament.”

Then the lady returned to the palace, and she said to her husband, “Wherefore hast thou concealed thy child from me?” The Prince said, “I will do so no longer.” He sent messengers for Kilhuch, and the youth was brought into the palace.

Now when his step-mother saw him she was fearful that he would take the whole of his father’s possessions away from her own child, for it was predicted to her by the crone that she would have a son. So she said to him when she looked on him, “It were well for thee to have a wife.” The youth answered, “I am not yet of an age to wed,” but although he said this he was well grown at the time. His step-mother said to him, “I declare to thee that it is thy destiny not to be suited until thou obtain Olwen, the daughter of Yspaddaden, the Chief of the Giants, for thy wife.”

Hearing that name the youth blushed, and the love of the maiden named was diffused through all his frame, although he had never seen her. He went to his father and he told him that it had been declared to him that he would never be suited until he had obtained the daughter of Yspaddaden for his wife. “That will not be hard for thee to do,” said his father, “for King Arthur is thy cousin, and he will aid thee. Go to Arthur, therefore. And ask him to cut thy hair, as great lords cut the hair of youths who are dear to them. And as he cuts thy hair ask it of him as a boon that he obtain for thee Olwen, the daughter of Yspaddaden.” Then Kilhuch mounted his steed and rode off to the Court of King Arthur.

“I crave it as a boon,” said Kilhuch, “that thou, King Arthur, cut my hair.” “That shall be granted thee,” said the King. “To-morrow I will do it for thee.” Then, on the morrow, King Arthur took a golden comb, and scissors whereof the loops were of silver, and he made ready to cut Kilhuch’s hair.

All King Arthur’s warriors and chieftains were in the hall, and Gwenhuivar, Arthur’s wife, was there also, when the King did honour to Kilhuch by cutting his hair for him. And the chief story-teller of the Island of Britain was there, and to the King, and to the King’s warriors and chieftains, and to Kilhuch he told a story.

THE STORY OF PUIL, PRINCE OF DYVED

How Puil Went Into Annuvin, the Realm of Faerie

One day in the summer it came into the mind of Puil, Prince of Dyved, to go hunting, and the place in all the seven Cantrevs of Dyved that he chose to go hunting in was the Vale of the Cuch. Early in the morning he went there; he unloosed his hounds in the wood, he sounded his horn, and he began the chase.

As Puil followed his hounds he lost the companions who had come with him. Still he went on. He came in sight of a glade that was deep in the wood, and then he saw that he was alone. He heard the cry of hounds coming from a direction opposite to that in which his own hounds were going. And as his hounds came to the edge of that glade he saw a stag there; it was at bay before hounds that were not his. Then, as he came on with his hounds, those other hounds flung themselves on the stag and brought it down.

It was a great stag. Nevertheless, Puil did not examine it for a while, so taken was he with the sight of the hounds that had pulled the stag down. For these hounds had bodies that were shining white, and they had red ears, and as the whiteness of their bodies shone so did the redness of their ears glisten. Never in all the world had Puil seen hounds that were like these hounds. For a while he looked on them, and then he drove them off, and he set his own hounds to kill the stag.

Then, just as he had done this, he saw a horseman come out of the wood, riding towards him. He was on a large, light-grey steed, and he had a hunting horn around his neck; he wore a hunting dress that was of grey woollen. And when the horseman came near he spoke to Puil, saying: “Chieftain, I know who thou art—Puil, Prince of Dyved—but I shall not give thee any salutation.”

Then said Puil: “Art thou then of such great state that thou thinkest it beneath thee to give me salutations?” “I am of great state,” said the stranger, “but it is not the greatness of my state that prevents my giving thee salutations.” “What is it then?” asked Puil. “Thine own discourtesy and rude behaviour,” answered the stranger.

Said Puil: “What rudeness and discourtesy have I shown, O Chieftain?” “Great rudeness and great discourtesy,” answered the stranger. “Greater rudeness and greater discourtesy I never saw than yours in driving away hounds that were killing a stag and then setting your own hounds upon it. That was indeed a great rudeness.” “A great rudeness indeed,” said Puil, acknowledging the wrong he had committed.

Then said Puil: “All that can be done I will do to redeem thy friendship, for I perceive that thou art of noble kind.” “A crowned King am I in the land that I come from,” said the stranger. “Lord,” said Puil, “show me how I may redeem thy friendship.”

Said the stranger: “I am Arawn, a King of Annuvin.1 Thou canst win my friendship by championing my cause. Know that Annuvin has another King, a King who makes war upon me. And if thou shouldst go into my realm and fight that King thou wouldst overthrow him, and the whole of the realm would be mine.” “Lord,” said Puil, “instruct me; tell me what thou wouldst have me do and I will do it to redeem thy friendship.”

The King of Annuvin then said to Puil: “I will put my own appearance upon thee and I will take thine appearance upon myself, for it is in my power to do these things. And in my semblance thou shalt go into my kingdom. There thou shalt stay for the space of a year from to-morrow, and thereafter we shall meet in this glade.” “Yes, Lord,” said Puil, “but how shall I discover him whom I am to do battle with?” “One year from this night,” said the King of Annuvin, “is the time fixed for combat between him and me. Be thou at the ford in my likeness. With one stroke that thou givest him he will lose life. And if he should ask thee to give another stroke, do not give it, no, not if he entreat thee even. If thou shouldst give another stroke he will be able to fight thee the next day as well as ever.” “If I go down to thy kingdom,” said Puil, “and stay there in thy semblance for a year and a day, what shall I do concerning my own dominions?” “As to that,” said the King of Annuvin, “I will cause, for I have such power, that no one in thy dominions, neither man nor woman, shall know but that I am thee. I will go there and rule in thy semblance and in thy stead.” “Then gladly,” said Puil, “will I go down into Annuvin, thy kingdom, and win thy friendship by doing what thou askest me to do.” “Clear shall be thy path, and nothing shall detain thee until thou comest into my kingdom, for I myself will be thy guide.” And saying this, the King of Annuvin, who had come into the wood with his hounds for no other purpose than to bring Puil into his realm on that day, conducted him into Annuvin.

And having brought him before the palace and the dwellings, he said: “Behold the court and the kingdom. All is in thy power from this day until a year from to-morrow. Enter the court; there is no one there who will not take thee for me. And when thou seest what is being done thou wilt know the customs of the place.” When he had said this the man who had been with Puil went from his sight.

Then Puil, Prince of Dyved, went into that strange court, and there he saw sleeping-rooms, and halls, and chambers, that were the most beautiful he had ever looked on. And there came pages to him who took off his hunting dress, and clothed him in a vesture of silk and gold. All who entered saluted him. Then they brought him into the feasting-hall, and he sat by the side of a lady who had on a yellow robe of shining satin, and who was the fairest woman that he had ever yet beheld. He spoke with her, and her speech was the wisest and the most cheerful that he had ever listened to. There were songs with the feasting. And of all the courts of Kings on the earth this court of Annuvin was, to the mind of Puil, the best supplied with food and drink, with vessels of gold and with royal jewels.

A year went by. Every day for Puil there was hunting and minstrelsy, there was feasting and discourse with wise and fair companions. And then there came the day on which the combat of the Kings was to take place, and even in the furthest parts of the realm the people were mindful of that day.

Puil went to the ford where the combat was to be, and the nobles of Arawn’s court went with him. And when they came to the ford they saw that Havgan, the King against whom the battle was to be, was coming from the other side. Then a knight arose and spake, saying: “Lords, this is a combat between two Kings, and between them only. Each claimeth of the other his land and territory. This combat will decide it. And do all of you stand aside and leave the fight to be between the Kings.”

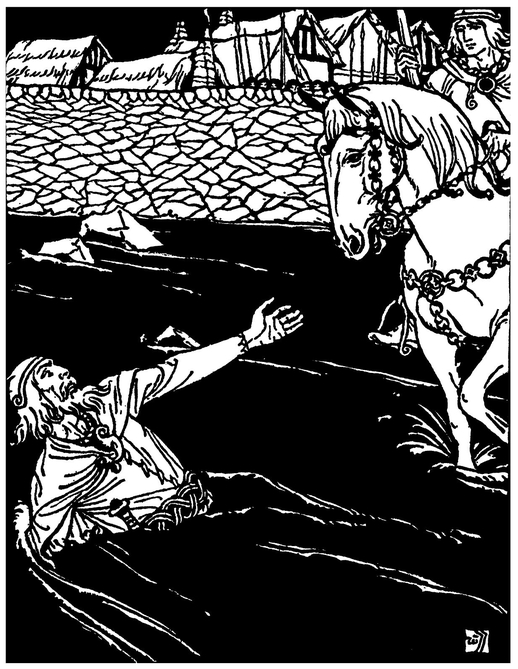

Thereupon Puil in the semblance of Arawn approached Havgan. They were in the middle of the ford when they encountered. Puil struck Havgan on the centre of the boss of his shield, so that his shield was broken in two, and his armour was broken, and Havgan himself was flung on the ground over the crupper of his horse, and he received a deadly blow. “O Chieftain,” he cried, “what right didst thou have to cause my death? I was not injuring thee in any thing; I know not wherefore thou wouldst slay me. But since thou hast begun to slay me, complete thy work.” “Ah, Chieftain,” said Puil, “I may yet repent of what I have done to thee. But I will not strike thee another blow.” “My lords,” said Havgan then, “bear me hence, for my death has come, and I shall no more be able to uphold you.” “My nobles,” said Puil, speaking as Arawn, “take counsel, and let all who would be my subjects now come to my side. It is right that he who would come humbly should be received graciously, but he that doth not come with obedience shall be compelled by force of swords.” “Lord,” said the nobles, “there is no King over the whole of Annuvin but thee.” And thereupon they gave him homage. And Puil, in the likeness of Arawn, went through all the realm of Annuvin, and he received submission from those who had been Havgan’s subjects, so that the two halves of the kingdom were in his power.

Thereupon he went to keep his tryst with Arawn. When he came into the glade in the wood the King of Annuvin was there to meet him and each rejoiced to see the other. “Verily,” said Arawn, “may Heaven reward thee for what thou hast done for me. When thou comest thyself to thy own dominions,” said he, “thou wilt see what I have done for thee.”

“But since thou hast begun to slay me, complete thy work.”

Then Arawn, King of Annuvin, gave Puil back his own proper semblance, and he himself took on his own. Arawn went back to the realm of Annuvin, and Puil, Prince of Dyved, went back to his own country and his own dominions, and was lord once more of the seven Cantrevs of Dyved.

After he had been a while in his own country and dominions, Puil inquired of his nobles how his rule had been in the year that was past, compared with what it had been before. “Lord,” said his nobles all, “thy wisdom was never so great before, and thou wast never so kind or so free in bestowing gifts, and thy justice was never more worthily shown than in this year.” “By Heaven,” said Puil, “for all the good you have enjoyed, you should thank him who hath been with you, for this is the way matters have been.” And thereupon Puil related to his nobles all that had happened. “Verily, Lord,” said they, “render thanks unto Heaven that thou hast made so good a friendship.”

After that the friendship between Puil and Arawn was made even stronger. Each sent unto the other horses, and grey-hounds, and hawks, and all such jewels as they thought would be pleasing to each other. And by reason of his having dwelt a year in Annuvin he lost the name of Puil, Prince of Dyved, and he was called Puil, Chief of Annuvin, from that time forward.

Now when the story-teller had told of Puil’s life so far, Kai said, “By the hand of my friend, this hunting was a fair adventure for Puil.” Arthur had combed out Kilhuch’s hair with the golden comb, and now he took the scissors whereof the loops were of silver, and he began to cut the hair. Then the story-teller who was in the hall, told:

THE STORY OF PUIL, PRINCE OF DYVED

How Puil Won Rhiannon for His Wife, and How Rhiannon’s Babe Was Lost to Her

It is told of Puil that once, while a feast was being prepared for him in his chief palace, he arose and went to walk and came to a mound that was above the palace, and went to the top of it. “Lord,” said one of those who were with him, “it is peculiar to this mound that whosoever sits upon it cannot go thence without receiving a blow or seeing a wonder.” “I fear not to receive a blow,” said Puil, “with so many valiant men around me, and as to a wonder, I should gladly see one. I will therefore go and sit upon the mound.”

And upon the mound he sat. And while he sat there he and those who were with him saw a lady on a horse of pure white, with a garment of shining gold upon her, coming along the highway; the horse seemed to move at a slow and an even pace, and to be coming towards the mound. “My men,” said Puil, “is there any amongst you who knows yonder lady?” “There is not, Lord,” said they. “Go, one of you, and meet her,” said Puil.

Then one of the men arose, and he came upon the road to meet her, and she passed by, and he followed as fast as a man on foot might follow. But the greater his speed, the further did the lady distance him. And when he saw that it profited him nothing to follow her, he returned to Puil, and he said to him, “Lord, it is idle for anyone in the world to follow her on foot.” “Then,” said Puil, “go to the palace and take the fleetest horse that thou seest, and go after her.”

The man went and took the horse and went forward on the highway. And he came to an open level plain, and he put spurs to his horse. But the more he urged his horse, the further was the lady from him. And yet she seemed to keep the same pace as before. Then his horse began to fail. The man returned to the place where Puil was, and he said: “Lord, it will avail nothing for anyone to follow yonder lady. I know of no horse in these realms swifter than this one, but all its swiftness did not help me to gain on her.” “Of a truth,” said Puil, “there must be some enchantment in this. Now let us go back to the palace.”

So they went back to the palace, and they partook of the feast that was prepared. The next day, after the first meal, they arose, and Puil said: “We will go as yesterday to the top of the mound. And do thou,” said he to one of his young men, “take the swiftest horse in the field and bring it along.” The young man did so, and they went towards the mound, taking the horse with them.

And no sooner had they sat down on the top of the mound than they saw the lady on the same horse, and in the same apparel, coming along the same road. “Behold,” said Puil, “the lady of yesterday. Make ready, youth, to learn who she is.” “My Lord,” said the youth, “that will I gladly do.”

The lady was opposite them then. The youth mounted his horse; and before he had settled himself in the saddle, she passed by, and there was a clear space between them. But her speed seemed no greater than it had been on the day before. Then the youth put his horse into an amble, thinking that for all the gentle pace that his horse went at, he should soon overtake her.

But soon he saw that this pace would not avail him, and so he gave his horse the reins. But still he came no nearer to her than when he went at a foot’s pace. The more he urged his horse the further the lady was from him, and yet she rode no faster than before.

When the youth saw that it availed him not to follow her, he returned to the place where Puil was. “Lord,” he said, “the horse can do no more than thou hast seen.” “I see indeed,” said Puil, “that it avails not that anyone should follow her. And by Heaven,” said he, “she must have an errand to someone, if her haste would allow her to declare it.”

They went back to the palace, and they spent the rest of the day in feasting. The next day, when it came towards evening, Puil said: “Let us go to the mound and sit there. And do thou,” said he to his page, “saddle my horse, and go with him to the road, and bring also my spurs with thee.” The youth did as he was bidden.

They went and they sat upon the mound, and ere they had been there but a short while, they beheld the lady coming by the same road, and in the same manner, and at the same pace. Then Puil said: “Bring me my horse.” And no sooner was he upon the horse than the lady passed him. He turned after her and followed her. His horse went bounding, and he thought that with the second step or the third he should come up with her. But he came no nearer to her than at first.

Then Puil urged the horse to his utmost speed, but that speed availed nothing; he could not come up with the lady. Then he cried out: “O maiden, for the sake of him whom thou best lovest, stay for me.” And when he said that, she turned around. “I will stay gladly,” she said, “and it were better for thy horse hadst thou asked me long since.”

She stopped, and she threw back that part of her headdress that covered her face. And she fixed her eyes upon him, and began to talk with him. “Lady,” he asked, “whence comest thou, and whereto dost thou journey?” “I journey on my own errand,” said she, “and right glad am I to see thee.” “My greetings unto thee,” said he. And saying that he looked on her, and he thought that all the beauty of all the maidens and ladies he had ever seen was as nothing compared to her beauty. “Lady,” said he, “wilt thou tell me aught concerning thy purpose?” “I will tell thee,” said she, “that my chief quest was to find thee.” “Behold,” said Puil, “this is to me the most pleasing quest on which thou couldst have come. And wilt thou tell me who thou art?” “I will tell thee, Lord,” said she. “I am Rhiannon, the daughter of Heveid.”

And then she said: “They sought to give me in marriage against my will, but no husband would I have, and that because of my love for thee, neither will I yet have one unless thou dost reject me. And hither have I come to hear thy answer.” “By Heaven,” said Puil, “this is my answer: If I might choose amongst all the ladies and damsels in the world, thee would I choose.” “Verily,” said she, “if thou art thus minded, make a pledge to meet me ere I am given to another.” “The sooner I may do so, the more pleasing will it be unto me,” said Puil. “I will have it that thou meet me this day twelvemonth at the palace of Heveid, my father,” said she, “and I will cause a feast to be prepared so that it will be ready against thy coming.” “Gladly,” said Puil, “will I keep this tryst.” “Lord,” said Rhiannon, “keep in health, and be mindful of thy promise; and now I will go hence.”

And so they parted. Puil went back to those who were in his palace. But whatever questions they asked him respecting the damsel, he always turned the discourse upon other matters. And so a year went by.

Then it came to the day that was a twelvemonth from the time that Rhiannon had spoken with him. Puil caused a hundred of his knights to equip themselves and go with him to the palace of Heveid. And when they came to that palace Puil was greeted with joy and gladness, and he saw that a feast had been made ready against his coming.

Heveid received Puil as the man to whom his daughter would be given as a bride. And when they went into the feast, Heveid sat on one side of Puil, and Rhiannon sat on the other side, and there were songs with the feasting, and Puil, talking with Rhiannon, found that she was as wise and mirthful as she was lovely.

Now when the feast was at its height, Puil saw a young man enter the feasting-hall; he was clothed in a garment of satin, and he had the bearing of one who had power and wealth. He came to where Puil sat with Rhiannon, and he gave salutation to Puil. “The greeting of Heaven be unto thee, my soul,” said Puil. “Come thou and sit down.” “Nay,” said the young man, “I have a boon to ask thee.” Then said Puil, without thinking because of the great joy that was around him, “Whatsoever boon thou mayest ask of me, as far as I am able, thou shalt have it of me.” “Alas,” said Rhiannon, “wherefore didst thou give that answer?”

But the young man said exultantly: “Has he not given me my answer in the presence of these nobles?” “My soul,” said Puil, disturbed now, “what is the boon thou askest?” “The lady whom best I love is to be thy bride this night; I come to ask her of thee—that is the boon I crave. And also I would have the feast and the banquet that is in this place.” Then Puil was silent because of the answer he had given. “Be silent now as long as thou wilt,” said Rhiannon, “for never did a man make worse use of his wits than thou hast done. This is the man to whom they would have given me in marriage against my will. Now thou hast given me to him. He is Gwaul, the son of Clud, a man of great power and wealth. And because of the word thou hast spoken, bestow me upon him, lest thou be shamed before these nobles for not keeping thy word.”

Then Puil was silent, not knowing what to say. “Lady,” said he, “never can I do as thou sayest.” Then said Rhiannon, speaking in a low voice, “Bestow me upon him, and I will cause that I shall never be his. Do this, I pray thee, and so keep thy word. But tell him that as for the feast and the banquet they cannot be given him, for they have already been bestowed. And I on my part will promise to become his bride this night twelvemonth.” “Lord,” said Gwaul, “it is meet that I have an answer to my request.” “As much of that thou hast asked me as in my power to give, thou shalt have,” said Puil. And then Rhiannon said, “As for the feast and the banquet that are here, I have bestowed them on the men of Dyved and the warriors that are with us. These I cannot suffer to be given to another person. But in a year from to-night a banquet shall be prepared for thee in this palace, that I may become thy bride.”

Gwaul was content with this. He went away. Then Rhiannon put into Puil’s hand a little bag. “See that thou keep it well,” she said. “And at the end of a year be thou here, and bring this bag with thee, and let thy hundred knights be in the orchard up yonder. And when he is in the midst of joy and feasting, come thou in by thyself, clad in ragged garments, and holding thy bag in thy hand. Go to him and ask of him for a boon your bagful of food. I will cause that if all the meat and liquor that are in these seven Cantrevs were put into it, it would be no fuller than before. And after a great deal has been put in, he will ask thee whether thy bag will ever be full. Say thou then that it never will, until a man of noble birth and of great wealth arise and press the food in the bag with both his feet, saying, ‘Enough has been put therein; and I will cause him to go and tread down the food in the bag, and when he does so, turn thou the bag, so that he shall be up over his head in it, and then slip a knot upon the thongs of the bag. Let there be also a bugle horn about thy neck, and as soon as thou hast bound him in the bag, wind thy horn, and let it be a signal between thee and thy knights in the orchard. And when they hear the sound of the horn, let them come down upon the palace.”

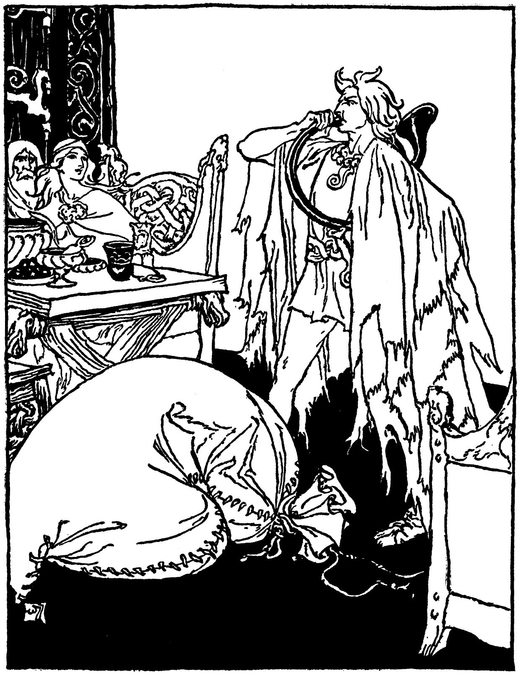

After that Puil went back to Dyved, as Gwaul went forth to his possessions. And they both spent that year until it was time for the feast at the palace of Heveid. Then Gwaul set out to the feast that was prepared for him, and he came up to the palace, and was received there with rejoicing. Puil, also, came. He went to the orchard with his hundred knights, as Rhiannon had commanded him, having the bag with him. And Puil was clad in coarse and ragged garments, and wore large, clumsy old shoes on his feet. And when they were at the height of the feast, he went towards the hall, and when he entered the feasting-hall, he went up and saluted Gwaul, the son of Clud, and his company, both men and women. “Heaven prosper thee,” said Gwaul, “and the greeting of Heaven be unto thee.” “Lord,” said Puil, “may Heaven reward thee. I have an errand unto thee.” “Welcome be thine errand, and if thou ask of me that which is just, thou shalt have it gladly.” “It is fitting,” answered Puil. “I crave but from want, and the boon that I ask is to have this small bag filled with food.” “A request within reason is this,” said Gwaul, “and gladly shalt thou have it. Bring him food,” he said then to the attendants. A great number arose and began to fill the bag, but for all that they put into it, the bag was no fuller than at first. “My soul,” said Gwaul, “will thy bag be ever full?” “It will not, I declare to Heaven,” said Puil, “for all that may be put into it, unless one possessed of lands, and domains, and treasure, shall arise and tread down with both his feet the food that is within the bag.” Then Rhiannon said unto Gwaul: “Arise up quickly and go and press down the food.” “I will do so willingly,” said he. So he rose up, and he put his two feet into the bag.

Then did Puil turn up the sides of the bag, so that Gwaul was over his head in it. Then did Puil shut up the bag and slip a knot on it. Then did he take the bugle horn that was around his neck, and blow a blast on it. The hundred knights who were in the orchard heard the bugle horn; they came quickly into the palace and the feasting-hall; they seized upon all who had come with Gwaul, and they put them in the dungeons of the palace.

Then Puil threw off his rags, and his old shoes, and his tattered array. And his knights, as each one came in, struck a blow upon the bag. “What is here?” one would say to the other. “A badger,” the other would say. And so they went on striking on the bag in which Gwaul was held. And every one as he came in would ask: “What game are you playing in this way?” “The Game of Badger in the Bag,” he would be told. And this was how Badger in the Bag was first played.

“Lord,” said the man in the bag, “if thou wouldst hear me, I deserve not to be killed in a bag in this way.” “Lord,” said Heveid to Puil, “he speaks truth. It were fitting that thou listen to him, for he deserves not to die in this way.” “Verily,” said Puil, “I will do thy counsel concerning him.” Then Rhiannon said: “Take a pledge from him that he will never seek to revenge himself for what has been done to him. And further: thou wilt have to satisfy minstrels and suitors with gifts. Let him give unto them in your stead out of his treasures. And that will be punishment enough for Gwaul.” “Gladly will I do all that,” said the man in the bag.

And upon that Puil, taking the counsel of Heveid and Rhiannon, let Gwaul out of the bag, and liberated his henchmen also. “Verily, Lord,” said Gwaul, “I am greatly hurt, and have many bruises; I have need to be anointed; with thy leave I will go forth.” “Willingly,” said Puil, “mayest thou do so.” And so Gwaul and his henchmen left the palace, and Gwaul went towards his own possessions.

And then the hall was set in order for Puil and his knights, and Heveid and his people, and they went to the tables, and they sat down, and the feasting began all over again. And now Puil sat with Rhiannon, and they feasted, and had song, and spent the night in mirth and tranquillity. And when the time came that they should sleep, Puil and Rhiannon went into their own chamber.

Then did he take the bugle horn and blow a blast on it.

The next morning, at the break of day, Rhiannon said to her husband: “My Lord, arise, and begin to give gifts to the minstrels who attended the feast, and to the suitors who have come seeking something for themselves. Refuse no one to-day that may claim thy bounty.” “That I will gladly do,” said Puil. And he arose and went into the hall, and he caused silence to be proclaimed, and he desired the minstrels and all the suitors to show and to point out what gifts were to their wish and desire. And this being done, the feast went on, and Puil denied no one anything while the feast lasted. And when the feast had ended Puil said to Heveid, “My Lord, with thy permission I will set out for Dyved, for with Rhiannon I would go hence.” “Certainly,” said Heveid. “And may Heaven prosper you.”

So Puil and Rhiannon set out for Dyved the next day. They came to the palace of Narberth and there they abode. And there came to them the chief men and the most noble ladies of the land of Dyved, and of these there were none to whom Rhiannon did not give some rich gift, either a bracelet, or a ring, or a precious stone. And Puil and Rhiannon ruled the land prosperously both that year and the next.

It is told that there came a time when the nobles of the land came to Puil with words that troubled him greatly. Rhiannon, they said, had no children; they asked that Puil take another wife so that a son born to him might rule over them and over Dyved. “Thou canst not always continue with us,” they said to him.

Then said Puil, greatly troubled: “Come to me in a year from this, and I will talk this matter over with you.” The nobles agreed to this, and they went away. And then, greatly to the joy of Puil, before the end of the year, a child was born to Rhiannon.

Great was Rhiannon’s joy when the boy was born, but it was not long until her joy was changed into sorrow. Six women were sent into her chamber to tend the child and to mind Rhiannon. At midnight the mother slept. And the women who were there to watch over her and over the child slept also. The women wakened up before it was day; they looked towards where they had laid the child, and behold! the child was not there. “Oh,” said one of the women, “the boy born to our Lord Puil is lost. It will be little punishment for our neglect in watching over him if we are all burned for this.” Said one of the women then: “Is there any plan by which we could save ourselves?” “There is,” said another woman. “Listen to me, and I will tell you a way by which we can save ourselves.”

Then this woman said: “There is a stag-hound with a litter of whelps outside. Let us kill one of the whelps, and rub the blood of the whelp near Rhiannon, and then declare to all that she killed her son in a madness that came on her—killed him and then threw his body to wolves that were outside.”

The women agreed to this dreadful counsel. They killed one of the stag-hound’s litter, and they spread its blood near Rhiannon. Towards morning she awoke, and the first words that she said were: “Women, where is my son?” “Lady,” said they all, “ask us not concerning thy son; we have naught but the blows and bruises got by struggling with thee, and of a truth we never saw any woman so violent as thou, for it was of no avail to contend with thee. Hast thou not thyself slain and flung away thy child? Claim him not therefore of us.” “For pity’s sake,” said Rhiannon, “charge me not falsely. Heaven knows all, and if you say this thing from fear, I declare, before Heaven, that I will defend you.” “Truly,” said they, “we would not bring evil on ourselves for anyone in the world.” “For pity’s sake,” said Rhiannon, “you will receive no evil by telling the truth.” “The truth is that we strove to save the child from being slain by thee, and that we could not save him.” And for all her words, whether fair or harsh, Rhiannon received but the same answer from the women.

And when Puil arose, the story that the women told came to his ears, and he was made very sorrowful. The story went through all the land. Then his nobles came once more to Puil, and they besought him to put away his wife, because of the great crime she had done. Puil answered, telling them that he would not put Rhiannon away. “If she has done wrong,” he said, “let her do penance for it.”

Her husband’s words seemed wise to Rhiannon. She preferred to do penance rather than contend any more with the six women. And the penance that she took upon herself was this: that she should sit every day for seven years near the horse-block that was without the gate of the palace, and that she should relate her story to all who came that way and who did not know it, and that she should offer the guests and strangers, if they would permit her, to carry them upon her back into the palace. And so it was with Puil’s wife, Rhiannon.

In another part of Dyved there lived a lord whose name was Teirnon, and this lord was one of the best and the kindest of men. And unto his house there belonged a mare than which neither mare nor horse in all the land was more beautiful. On the first day of May every year this mare had a foal, but no one after knew what became of the foal; it was gone before anyone saw it.

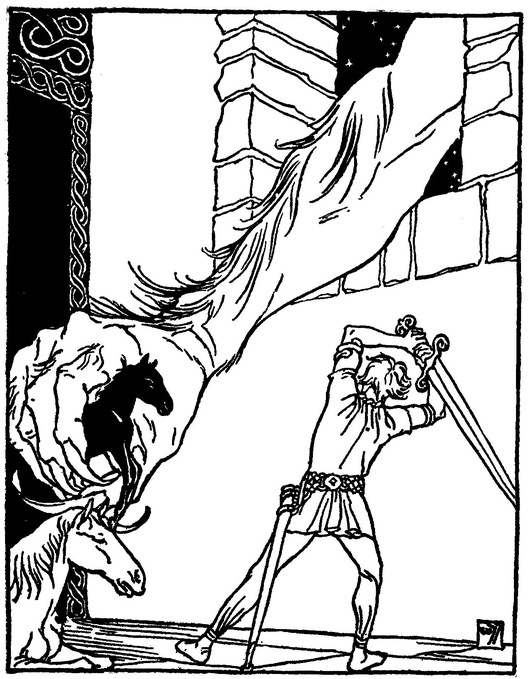

One night, when it was coming near May Day, Teirnon was talking with his wife, and he said, “How simple we are, wife! Our mare foals every year, and we have none of her colts. Why should we not watch and mind her when she comes near to foaling? The vengeance of Heaven be upon me, if I learn not what it is that takes away her foals.” So Teirnon said, and he caused the mare to be brought into the house. And on May Day he armed himself, and he watched the mare through that night.

The mare had a large and beautiful foal. Teirnon saw it standing up beside the mare. And while he was wondering at its size he heard a great tumult, and after the tumult, behold! a great claw came through the window and into the house, and it seized the foal by the mane. Then Teirnon drew his sword, and he struck off the arm that had the claw at the elbow, so that portion of the arm together with the foal, was left in the house with him. And then he heard a tumult and a wailing outside.

Teirnon opened the door of his house and he rushed out towards where he heard the noise, but he could not see the cause of the tumult because of the darkness of the night. Still he rushed in the direction of it. Then he remembered that he had left the door of his house open, and he went back to it. And when he came to his door, behold! there was a child laid, an infant boy in swaddling clothes, wrapped in a mantle of satin. He took the boy, and he saw that he was very strong for the age he seemed to be.

Then Teirnon drew his sword.

Then Teirnon closed the door of his house and he went into the chamber where his wife was. “Lady,” said he, “art thou sleeping?” “I was asleep,” his lady said, “but as soon as thou camest in I awakened.” “Here is a child,” he said, “a boy for thee, if thou wilt, since thou hast never had one.” “My Lord,” said Teirnon’s wife, “what adventure is this?” Then Teirnon told her all that had befallen. “Verily, Lord,” said she, “what sort of garments are on the boy?” “A mantle of satin,” he told her. “He is then a boy of noble lineage,” she replied. And then she said: “My Lord, I will rear this boy as my own.”

They had the child baptized, and they gave him a name, and they reared him in their court until he was a year old. Before that year was over he could walk stoutly, and he was larger than a boy of three years old, even one of good growth and size. He was nursed a second year, and then he was as large as a child of six years old. At the end of the fourth year he would get the grooms to allow him to take the horses to water. Marvellously indeed did the boy grow.

One day his wife said to Teirnon: “Where is the colt that thou didst save on the night that thou didst find the boy?” “I commanded the grooms to take charge of it,” said Teirnon. “Would it not be well, Lord,” said she, “to have the colt broken in and given to the boy, seeing that on the same night thou didst find the boy the colt was foaled?” “I will allow thee,” said Teirnon, “to give the boy the colt.” “Lord,” said she, “may Heaven reward thee; I will give it to him.” So the horse was given to the boy, and the grooms broke the horse in so that he was able to ride it.

About this time tidings of Rhiannon and her punishment came to Teirnon and his wife. And Teirnon, because of his friendship for Puil and because of the pity he felt for Rhiannon, inquired closely concerning for all who came to his court. Often he lamented the sad history he had heard, and often he pondered within himself, and often he would look steadfastly upon the boy.

Everything in Puil’s appearance was known to Teirnon, for of yore he had been one of his followers. And as he looked upon the boy he had reared, it seemed to him that he had never seen so great a likeness between father and son as there was between this boy and Puil, Chief of Annuvin. Then a time came when he told his wife all that was in his mind, and he told her that they, perhaps, did wrong in keeping the boy with them while so noble a lady as Rhiannon was undergoing a penance that had to do, perhaps, with the loss of him.

Then his wife agreed with him that the boy should be taken to Puil’s palace to find out if it might be that he was Puil’s son. So Teirnon equipped himself, and no later than the next day he set out for Puil’s palace at Narberth, and the boy went with him, mounted on the horse that Teirnon’s lady had given him.

As they drew near to the palace they beheld Rhiannon sitting beside the horse-block. And when they came opposite to her, she said: “Chieftain, do not go any further thus; I will bear thee and those who are with thee on my back into the palace, and this is my penance for having slain my own son.” “Oh, fair lady,” said Teirnon, “think not that I will be one to be carried on thy back.” “Neither will I,” said the boy. “Truly, my soul,” said Teirnon to her, “we will not have it so.”

They went forward to the palace, and there was joy at their coming, for Teirnon was liked well by Puil. And when they had washed, Teirnon and the boy sat down to a feast that had been prepared for them, and Teirnon sat between Puil and Rhiannon, and the boy sat at the other side of Puil. And after they had eaten, discourse began.

Teirnon’s discourse was all about the adventure of the mare and the boy, and how he and his wife had reared the boy as their own. And all who were in the hall looked on the boy. Then Teirnon said: “I believe there is none of this host who will not perceive that the boy is the son of Puil.” “There is none,” all of them said, “there is none who is not certain thereof.” “I declare to Heaven,” said Rhiannon, “if this be true, there is indeed an end to all my troubles.” “Teirnon,” said Puil, “Heaven reward thee that thou hast reared the boy up to this time, and being of gentle lineage, it were fitting that he repay thee for it.” “My Lord,” said Teirnon, “it was my wife who nursed him, and there is no one in the world so afflicted as she at parting with him. It were well that he should bear in mind what I and my wife have done for him.” “I call Heaven to witness,” said Puil, “that while I live I will support thee and thy possessions, as long as I am able to preserve my own. And when he has power, he will more fitly maintain them than I.”

After Teirnon had put the boy into Puil’s charge, they had counsel together and they agreed to give him over to one of the great men of the land, to Pendaran Dyved, to be brought up by him. “And you both shall be my companions,” said Puil to Teirnon, “and both shall be foster-fathers unto him.” “This is good counsel,” said all who were present.

After that Teirnon set out for his own country and his own possessions. And he went not without being offered the fairest jewels, and the finest horses, and the choicest dogs; but he would take none of them.

The boy was named Prideri by his mother. He was brought up carefully as was fit, so that he became the fairest youth, and the most comely, and the best skilled in all good games, of any in the kingdom. And thus passed years and years away, until the end of Puil’s, the Chief of Annuvin’s, life came and he died. Then Prideri ruled over the seven Cantrevs of Dyved prosperously, and added three other Cantrevs to his possessions, and he was beloved by his people, and by all around him.