II

HOW THEY SOUGHT THE MAID OLWEN

And now Kilhuch’s hair was cut by the hand of Arthur. Then all the champions and warriors in the hall gathered around them to hear what boon the youth would ask of the King. “Whatsoever boon thou mayest ask, thou shalt receive it, be it what it may that thy tongue shall name,” said King Arthur. “Pledge the truth of Heaven and the faith of thy kingdom thereof,” said Kilhuch. “I pledge it thee, gladly.” “I crave of thee then, that thou obtain for me Olwen, the daughter of Yspaddaden, and this boon I seek likewise at the hands of thy warriors. I seek it from Kai and Bedour, and the hundred others who are here.”

Then said Arthur, “I have never heard of the maiden of whom thou speakest, nor of her kindred, but I will gladly send messengers in search of her. Give me time to seek her for thee.” The youth then said, “I willingly grant from this night to that at the end of the year.”

King Arthur thereupon sent messengers to every land to seek for the maiden who was named Olwen. At the end of the year the messengers returned without having gained any more knowledge or intelligence concerning her than on the day they went forth.

And when the year had come to its end Kilhuch said: “Everyone has received his boon, and yet I lack mine. I will depart from this place, and the blame for my going will be upon King Arthur.” Then said Kai: “Rash youth! Dost thou lay blame on Arthur? Go with us, and we will not part from each other until thou dost confess that the maiden exists not in the world, or until we obtain her for thee.” Kai rose up, and thereupon King Arthur called upon Bedour, who never shrank from any enterprise upon which Kai was bound. None was equal to him in swiftness throughout the Island. And although he was one-handed, three warriors could not shed blood faster than he on the field of battle. Another quality he had: his lance could produce a wound equal to those of nine opposing lances. And Arthur called upon Gwalchmai, because he never returned home without achieving the adventure of which he went in quest. He was the best of footmen and the best of knights. He was nephew to Arthur, the son of his sister and his cousin. And Arthur called upon his guide to go with them; as good a guide was he in a land which he had never seen as he was in his own. And he called upon one who knew all tongues to go with them also, and he called upon another, who, if they were in a savage country, could cast a charm and an illusion over them, so that none might see them whilst they could see everyone. And so, with Kai, and Bedour, and Gwalchmai, with the guide, and the one who knew all tongues, and the one who could cast a charm and an illusion, the youth Kilhuch went forth from Arthur’s Court in quest of Olwen, the daughter of Yspaddaden.

They went on until they came to a vast open plain. They saw a castle in the middle of it, and it seemed to them to be the fairest castle in the world. They went towards it; that day they journeyed until evening, and when they thought they were nigh the castle, they were no nearer to it than they had been in the morning. And the second and third day they journeyed, and even then scarcely could they reach so far. But at last they came nigh it. And when they were before the castle they beheld a vast flock of sheep, a flock boundless and without end. And upon the top of a mound there was a herdsman keeping the sheep.

They went nearer, and they saw that a mantle of skins was upon the man, and that by his side there was a shaggy mastiff, larger than a steed of nine winters old. And all the trees that were dead and burnt on the plain that mastiff had burnt with his breath down to the very ground.

Then said Kai to the one who knew all tongues: “Go thou and salute yonder man.” “Kai,” said he in reply, “I engaged not to go further than thou thyself.” “Let us go together then,” said Kai. Said the man of spells who was with them: “Fear not to go thither, for I will cast a spell upon the hound, so that he shall injure no one.” And this he did.

They went up to the mound where the herdsman was, and they said to him: “How dost thou fare, O herdsman! Whose are the sheep that thou dost keep, and to whom does yonder castle belong?” “Stupid are ye, truly,” said the herdsman. “Through the whole world it is known that this is the castle of Yspaddaden.” “And who art thou?” they asked. “I am Custennin, and my brother is Yspaddaden,” said the herdsman, “but he oppressed me because of my possessions. And ye, also, who are ye?” “We are men on an embassy from King Arthur, and we have come to seek Olwen, the daughter of Yspaddaden.” “O men, the mercy of Heaven be upon you, do not do that for all the world. None who ever came hither upon that quest has returned alive.”

Then Kilhuch went to the herdsman and told him who he was, and told him who his father and mother were. Also he gave unto him a ring of gold. The herdsman sought to put it on his finger, but it was too small for him, so he put it in his glove. When he went into his house he gave the glove to his wife to keep; she took the ring from the glove that was given her, and she said: “Whence came this ring? Thou art not wont to have good fortune.” And he said: “Kilhuch, the son of the daughter of Prince Anlod, gave it to me; thou shalt see him here in the evening. He has come to seek Olwen as his wife.” When he said that the herdsman’s wife was divided between joy and sorrow, joy because Kilhuch was her sister’s son and was coming to her, and sorrow because she had never known anyone depart alive who had come on that quest.

They came to the gate of Custennin’s dwelling, and when she heard their footsteps approaching, the woman ran with joy to meet them. They entered the house, and they were all served, and soon after they went forth to amuse themselves. Then the woman opened a stone chest that was before the chimney-corner, and out of it arose a youth with yellow curling hair. Said one: “It is a pity to hide this youth. I know that it is not his own crime that is thus visited upon him.” “This is but a remnant,” said the woman, Custennin’s wife. “Three and twenty of my sons has Yspaddaden slain, and I have no more hope of this one than of the others.” Then said Kai: “Let him come and be a companion with me, and he shall not be slain unless I also am slain with him.” It was agreed that the youth would go with Kai; then they ate.

Said the woman: “Upon what errand come you here?” “We come to seek Olwen for this youth,” said Kai. Then said the woman: “In the name of Heaven, since no one from the castle hath yet seen you, return again whence you came.” “Heaven is our witness, that we will not return until we have seen the maiden,” said they.

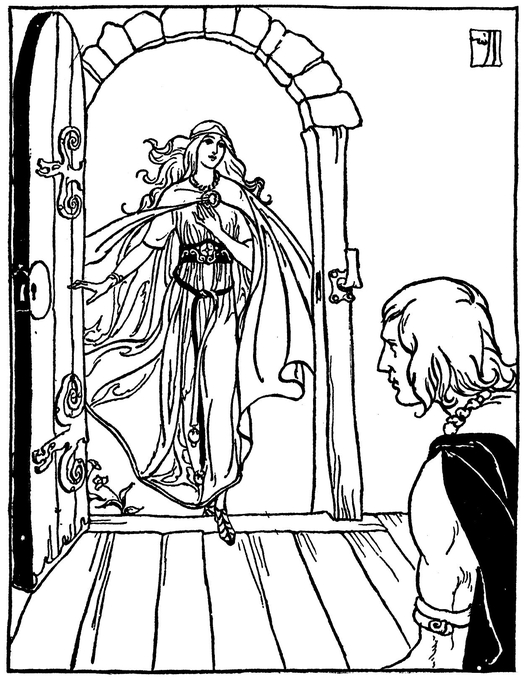

Said Kai: “Does Olwen ever come hither, so that she may be seen?” “She comes here every Saturday to wash her head,” said the woman, “and in the vessel where she washes, she leaves all her rings, and she never either comes herself or sends any messengers to fetch them.” “Will she come here if she is sent for?” “Unless you pledge me your faith that you will not harm her, I will not send for her,” said the woman. “We pledge our faith,” said all of them. So a message was sent, and Olwen came.

The maiden was clothed in a robe of flame-coloured silk, and about her neck was a collar of ruddy gold, on which were precious emeralds and rubies. More yellow was her head than the flower of the broom, and her skin was whiter than the foam of the wave, and fairer were her hands and her fingers than the blossoms of the wood anemone amidst the spray of the meadow fountain. The eye of the trained hawk, the glance of the three-mewed falcon, was not brighter than hers. Her bosom was more snowy than the breast of the white swan, her cheek was redder than the reddest roses. Whoso beheld her was filled with love. Four white trefoils sprang up wherever she trod. And therefore was she called Olwen, the Maiden of the White Footprints.

She entered the house, and sat beside Kilhuch upon the foremost bench; and as soon as he saw her he knew her. And Kilhuch said unto her: “Ah! maiden, thou art she whom I have loved; come away with me. Many a day have I loved thee.” “I cannot go with thee, for I have pledged my faith to my father not to go without his counsel, for his life will only last until the time of my espousal. But I will give thee advice if thou wilt take it. Go, ask me of my father, and that which he shall require of thee, grant it, and thou wilt obtain me; but if thou deny him anything, thou wilt not obtain me, and it will be well for thee if thou escape with thy life.” “I promise all this,” said Kilhuch.

Olwen entered the house.

Olwen returned to her chamber; then Kilhuch and all his friends set out for Yspaddaden’s castle.

They came to the castle; they slew the nine guards that were at the nine gates, and they died in silence; they slew the nine watch-dogs without one of them barking. They went through the gates and they went into the hall of Yspaddaden’s castle.

“The greeting of Heaven and of man be unto thee, Yspaddaden,” said they, when they went in. “And you,” said the enchanter, rising up, “wherefore have you come?” “We have come to ask thy daughter Olwen, for Kilhuch.” “Where are my pages and my servants? Raise up the forks beneath my two eyebrows which have fallen over my eyes, that I may see the fashion of him who would be my son-in-law.” And his pages and servants did so, and Yspaddaden looked at them. “Come hither to-morrow, and you shall have an answer,” he said.

They rose to go forth. Then Yspaddaden seized one of the three poisoned darts that lay beside him, and threw it after them. Bedour caught it, and flung it, and pierced the enchanter grievously with it through the knee. “A cursed ungentle son-in-law, truly,” said he. “I shall ever walk the worse for this rudeness, and shall ever be without a cure. This poisoned iron pains me like the bite of a gadfly. Cursed be the smith who forged it, and the anvil whereon it was wrought! So sharp it is!”

That night Kilhuch and his friends stayed in the house of Custennin the Herdsman. The next day with the dawn they arrayed themselves and proceeded to the castle. They entered the hall, and they said: “Yspaddaden, give us thy daughter in consideration of the dower which we will pay to thee. And unless thou wilt do so, thou shalt meet with thy death on her account.” Then said he: “Her four great-grandmothers and her four great-grandfathers are yet alive, and it is needful that I take counsel of them.” “Be it so,” answered they. They rose up to leave the hall. And as they rose up, he took the second dart that was beside him, and cast it after them. And the man who could work all spells caught it, and flung it back at him, and wounded him in the centre of the breast, so that it came out at the small of his back. “A cursed ungentle son-in-law, truly,” said he, “the hard iron pains me like the bite of a horse-leech. Cursed be the hearth whereon it was heated, and the smith who formed it! So sharp it is! Henceforth, whenever I go up a hill, I shall have a scant in my breath, and a pain in my chest.” By this time, Kilhuch and his friends had gone from the hall.

Yspaddaden seized the second of the poisoned darts and cast it after them.

The third day they returned to the palace. And Yspaddaden said to them: “Shoot not at me again unless you desire death. Where are my attendants? Lift up the forks of my eyebrows which have fallen over my eyeballs, that I may see the fashion of the man who would be my son-in-law.” Then they arose, and, as they did so, Yspaddaden took the third poisoned dart and cast it at them. And Kilhuch caught it and threw it vigorously, and wounded him through the eyeball. “A cursed ungentle son-in-law, truly,” said the enchanter. “As long as I remain alive, my eyesight will be worse. Whenever I go against the wind, my eyes will water; and peradventure my head will burn, and I shall have a giddiness every new moon. Cursed be the fire in which it was forged. Like the bite of a mad dog is the stroke of this poisoned iron.” By this time Kilhuch and his friends had gone from the hall.

The next day they came again to the palace, and they said: “Shoot not at us any more, unless thou desirest such hurt, and harm, and torture as thou now hast, and even more.” And after that Kilhuch went to him and said: “Give me thy daughter, and if thou wilt not give her, thou shalt receive thy death because of her.” Yspaddaden said to him: “Come hither where I may see thee.” They placed a chair for Kilhuch, and he sat face to face with the enchanter.

Said Yspaddaden: “Is it thou that seekest my daughter?” “It is I,” said Kilhuch. “I must have thy pledge that thou wilt not do towards me otherwise than is just,” said Yspaddaden, “and when I have gotten that which I shall name, my daughter thou shalt have.” “I promise thee that willingly,” said Kilhuch, “name what thou wilt.” “I will name now,” said the enchanter, “what I will have to get from thee for her dowry.”

Then said Yspaddaden, the father of Olwen, “It is needful for me to wash my head, and shave my beard on the day of my daughter’s wedding, and I require the tusk of the boar Yskithyrwyn to shave myself withal, neither shall I profit by its use if it be not plucked out of the boar’s head alive.”

Said Kilhuch, remembering that Olwen had told him that he must agree to do everything that her father asked him to do, “It will be easy for me to compass this, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Though thou get this,” said Yspaddaden, the Chief of the Giants, “there is yet that which thou wilt not get. There is no one in the world who can pluck the tusk out of the boar’s head except Odgar, the son of Aedd, King of Ireland.”

“It will be easy for me to bring Odgar, the son of Aedd, to the hunt of the boar and get him to pluck the tusk out of the boar’s head.”

“Though thou do that, there is yet that which thou wilt not do. I will not trust anyone to guard the tusk except Gado of North Britain. Of his own free will he will not come out of his kingdom, and thou wilt not be able to compel him.”

“It will be easy for me to bring Gado to the hunt, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Though thou get him to come, there is yet that which thou wilt not get. I must spread out my hair in order to have it shaved, and it will never be spread out unless I have the blood of the Jet Black Sorceress, the daughter of the Pure White Sorceress from the Source of the Stream of Sorrow on the bounds of Hell.”

“It will be easy for me to compass this, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Though thou get this, there is yet that which thou wilt not get. Throughout the whole of the world there is not a comb nor a razor nor a scissors with which I can arrange my hair, on account of its growth and its rankness, except the comb and razor and scissors that are between the two ears of the great boar that is called Truith.”

“It will be easy for me to get the comb and razor and scissors from the boar Truith, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“It will not be possible to hunt the boar Truith without Drudwin, the Little Dog of Greit.”

“It will be easy for me to bring to the hunting Drudwin, the Little Dog of Greit.”

“Though thou get the Little Dog of Greit, there is yet that which thou wilt not get. Throughout the world there is no huntsman who can hunt with this dog, except Mabon, the son of Modron. He was taken from his mother when three nights old, and it is not known where he is now, nor whether he is living or dead.”

“It will be easy for me to bring Mabon to the hunting, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Though thou get Mabon, there is yet that which thou wilt not get. Gwynn, the horse that is as swift as the wave, to carry Mabon, the son of Modron, to the hunt of the boar Truith. His owner will not give the horse of his own free will, and thou wilt not be able to compel him.”

“It will be easy for me to compass this, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Though thou get the horse that is as swift as the wave, there is yet that which thou wilt not get. Thou wilt not get Mabon, for it is known to none where he is, unless it is known to Eidoel, his kinsman.”

“It will be easy for me to find him, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Though thou get him, there is that which thou wilt not get. Thou wilt have to have a leash made from the beard of Dillus the Bearded, for that is the only leash that will hold the hound. And the leash will be of no avail unless it be plucked from the beard of Dillus while he is alive. While he lives he will not suffer this to be done, and the leash will be of no use should he be dead, because it will be brittle.”

“It will be easy for me to compass this, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Though thou get this, there is yet that which thou wilt not get. The boar Truith can never be hunted without the son of Alun Dyved; he is well skilled in letting loose the dogs.”

“It will be easy for me to compass this, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“And the boar Truith can never be hunted unless thou get the hounds Aned and Aethlem. They are as swift as the gale of wind, and they were never let loose upon a beast that they did not kill it.”

“It will be easy for me to bring these hounds to the hunting, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Though thou get them, there is yet that which thou wilt not get,—the sword of Gurnach the Giant; he himself will never be slain except with his own sword. Of his own free will he will not give the sword to thee, either for a price or as a gift, and thou wilt never be able to compel him.”

“It will be easy for me to compass this, although thou mayest think it will not be easy.”

“Difficulties thou shalt meet with, and nights without sleep, in seeking these things, and if thou obtain them not, neither shalt thou obtain my daughter.”

“Horses shall I have, and chivalry; and my lord and kinsman Arthur will aid me in obtaining these things. And I shall gain thy daughter, and thou shalt lose thy life.”

“Go forward. And when thou hast compassed all these marvels, thou shalt have my daughter Olwen for thy wife.”