A CURIOUS THING HAPPENS WHEN MY TEJANO FRIENDS GATHER around a table. We might start off griping about work or family or the pinche traffic, but sooner or later our conversation takes a turn. Someone will mention a dream from the night before, about a lost little girl in a long white dress who kept running away, and how he’s had that same dream every few months for years now, and what could it mean? Then someone will say that, a few weeks ago, she heard someone creaking up the stairwell and thought it was her husband, pero no: he was away on a business trip; she was home all alone. And then someone will confess that she removed the antique mirror hanging in her hallway last week because her six-year-old kept seeing a strange lady in it. Suggestions are made for cleansings (“Sage is supposed to be good for that”) and curings (“If my abuelita was still around, she’d slide a bowl of water beneath your bed”) and purifications (“Have you tried that egg thing yet?”), each preceded with an earnest, “Not that I believe in this, but . . .” When we finally take our leave, shuffling en masse out the door, someone notices that the moon is waxing, which means one thing, or that it’s waning, which means something else, and we half-walk, half-run to our cars and quickly lock the doors.

Greg and I haven’t been here five minutes when I sense it will be another one of those nights. For starters, we’re visiting the ranch of the acclaimed painter Santa Barraza, whose very name means “saint” in Spanish. Growing up, one of her tías was a curandera who brought her along to Mexico for trainings and eventually opened a healing chapel in South Texas.1 Post-college, Santa started traveling to Mexico herself, studying Aztec, Mixtec, and Mayan art, pictographs, and philosophy. She then taught at places like the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and exhibited around the world before deciding she missed the desert landscape that inspired her work. In 2006, she bought nineteen acres near Kingsville and created a homestead with a studio. Decking its walls are life-size portraits of the icons of this region: La Virgen de Guadalupe pulsing a blue-veined heart inside her chest; La Malinche in a field of maguey with a fetus curled at her breast; La Llorona rising from a pool of water; Selena emerging from a house. Each woman shimmers beneath a spotlight in an explosion of red, yellow, purple, and blue, a monument to heritage and to dignity.

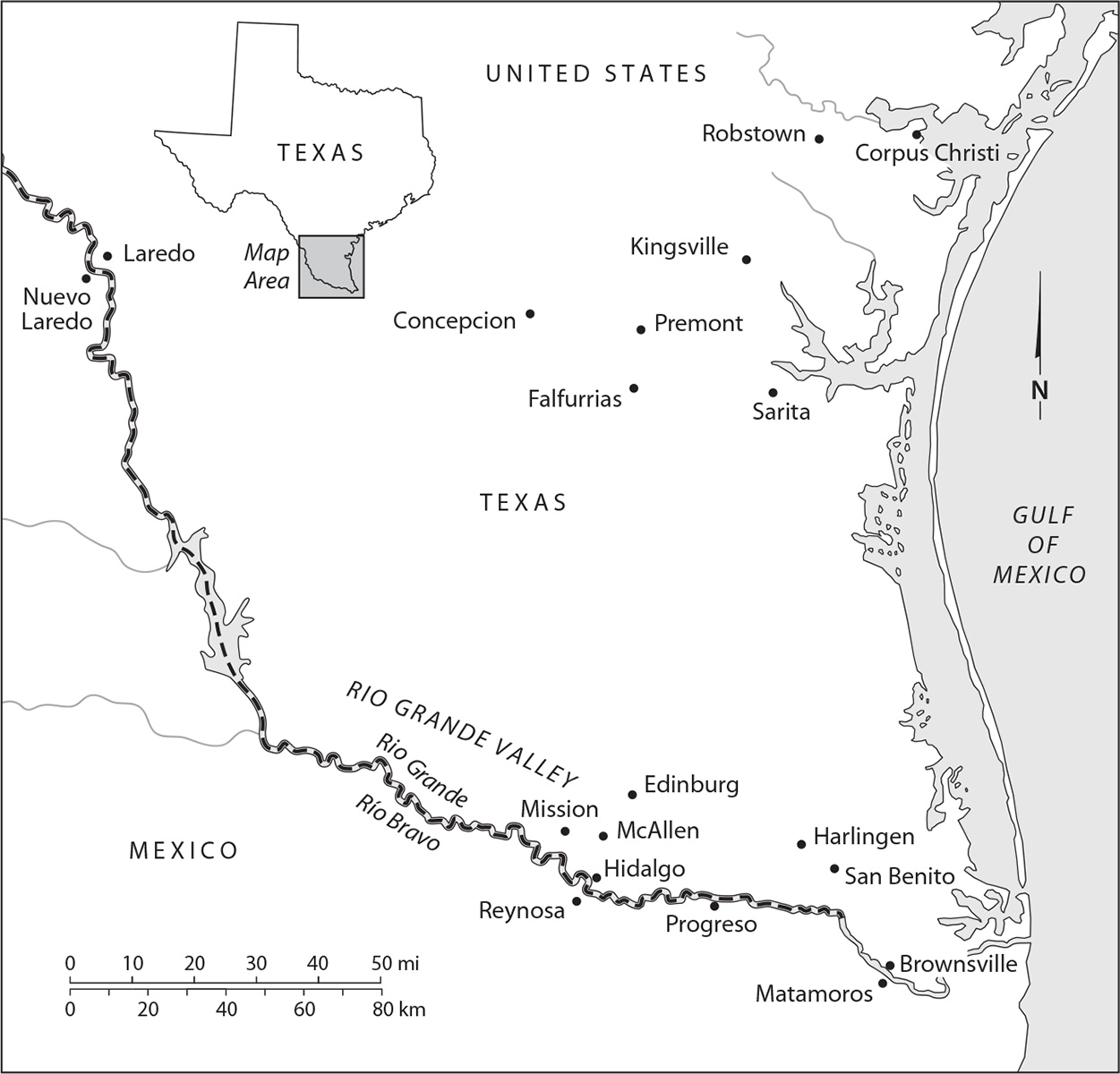

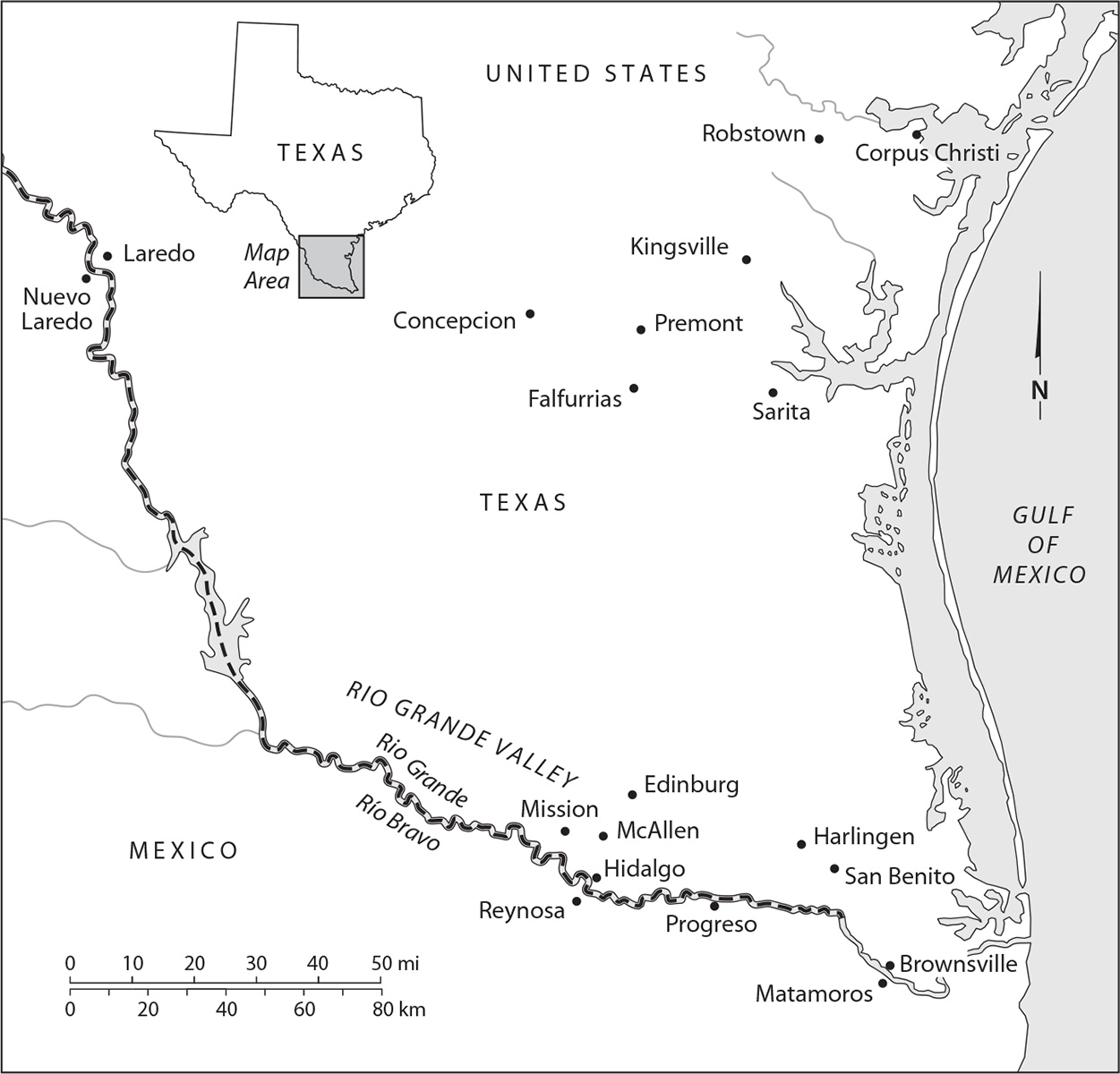

U.S.-MEXICAN BORDER

In high school, I bought postcards of Santa’s work at an art museum and have hung them on the walls of every residence I have lived in since. Entering her studio, then, feels like stepping into a memory palace, a labyrinthine space that is both fantastical and familiar. This sensation intensifies when, in the midst of an otherwise ordinary conversation, Santa asks if we’ve visited the miracle tree.

Shaking my head, I ask what makes it miraculous.

“It talks,” she says with the same nonchalance she might have said, “It sways.”

“With—words?”

Santa stares at me with her large dark eyes. “Yes, words.”

“What . . . does it sound like?”

“Real ugly. Like a demon. But it cured my sister Frances.”

Years ago, Frances suffered a stroke in Austin. Santa and their ninety-year-old father hurried to her bedside, carrying a Bible, a crucifix, a bottle of olive oil,2 and a leaf shed by the miracle tree. For hours he massaged the oil while Santa rubbed the leaf across Frances’s body, murmuring prayers. Then one of Frances’s toes began to wiggle.

“Suddenly, her leg lifted straight up in the air,” Santa says, flinging up an arm for emphasis. “The nurses couldn’t believe it. One ran into the room and said that shouldn’t have happened for a year.”

I was weaned on stories like this. Legions of tías and tíos told me about little girls flying from rooftops; about brujas wielding horsehair whips; about lady ghosts wailing down by the river. As a child, I so feared the power of el mal de ojo, I could not admire a newborn without touching her, lest she fall ill. Spirits inhabited even inanimate objects. I talked to our cars and wept when they were sold. Refused to part with old toys or clothing. Splashed water on all that was tainted. This half of me, the part steeped in culture and memory, believes in miracles. Shivers at their mention.

An inner skeptic, however, was born in journalism school and nurtured in a succession of newsrooms. Editors trained me to hunt for veracity rooted in certifiable fact. The only way they’d believe in a talking tree is if I chopped one down, dragged it into their office, and interrogated it in front of them. While I appreciated the reasons for this rigidity, it eventually grew limiting, so I gravitated toward the more freewheeling form of creative nonfiction, where verifiable facts are spun into truths (and, if you’re really lucky, Truth). In this genre, the question is not whether a tree can talk but why someone would wish it so.

I glance over at Greg, clad in his trademark black. We met in junior high, when we used to spend our weekends roaming the halls of Sunrise Mall. He couldn’t escape Corpus fast enough either, and a decade of travels had whisked him across Spain, Argentina, Japan, and Mexico before crash-landing him back here. Over the years, we have traveled many miles together for his art and my prose, and in the process, he’s become my barometer for possibility. When his eyes meet mine, we grin. Time for a road trip.

ACCORDING TO SANTA, the miracle tree belongs to an elderly woman who lives near Premont, a town of 2,700 about seventy miles southwest of Corpus. The farm road out there passes through land unfathomably vast and lined with cotton fields and oil wells. There are neither forests nor hills out here, no water beyond the pools that appear up ahead and then vanish. Predatory birds soar overhead. Cactus bloom from rooftops. Hand-painted crosses rise from the ditches.

Eventually we reach Broadway, Premont’s main thoroughfare—a string of boarded storefronts and an abandoned elementary school tangled in weeds. The electronic sign at Amanda’s BBQ flashes “Viva Mexico!” while a gas station advertises “Tacos, Gas, Beer.” The local bank is called Cowboy Country Federal Credit Union.

We polish off a leaden meal at Oasis, one of the town’s last standing restaurants. The food is cheap—hamburgers for $3.99—and artery-blocking. Chicken-fried steak. Chicken-fried chicken.3 Battered green beans. Gizzards and gravy. Menudo and tortillas. Chalupas and quesadillas. The hybrid menu matches the hybrid clientele, a blend of Tejano families and sunbaked white men in work boots and jeans, all dining in booths patched with duct tape so the springs don’t spill out. Our waitress asks where we are from.

When traveling, I field this question regularly, but no one is ever satisfied with my response. “You don’t seem Texan,” they say, as if expecting me to whistle for my horse or spit a wad of chew. When Tejanos question my origins, however, I feel like I’ve been gone so long, I’ve become unrecognizable—an outsider to the community I consider my own.

“Here?” she asks, brow crinkled.

“South Texas,” I say, a bit defensively.

“Corpitos,” Greg clarifies, which makes us all laugh. Corpitos is a nickname for Corpus Christi that denotes both affection and deprecation.

“Oh, Corpitos.” She smiles as if to say, You’re still not one of us—but you’re close.

After cruising Broadway a couple more times, we pull into Lopez Tire Co. to ask for directions. It is a bitter-cold day, so cold the weatherman instructed everyone to haul in their pets and plants last night. South Texans can endure triple digits with aplomb, but when the thermometer dips below fifty, we panic. The last time Corpitos experienced an icy rain, police responded to more than 200 vehicular accidents within a seventeen-hour period. Every school, mall, and bridge shuttered for miles.

A Tejano with a handlebar moustache trots out to greet us, rubbing his shoulders and shivering.

“We’re, uh . . . we’re looking for the tree,” I say.

No need to clarify: he promptly gives directions. When I ask how we’ll recognize it, his eyes donut: “Es gigantisimo!”

We follow 716 until it ends, past farmland and ranchitos, past jackrabbits and nopalitos, then turn left. In the distance soars a solitary tree, perhaps ten feet higher than the nearest telephone pole. With its sea-green mane undulating in the wind, it resembles an arboreal mermaid presiding over miles of scrub brush. A chain-link fence surrounds the tree, and as we draw near, we see that it has been interwoven with rosaries, maybe a hundred or more. Plastic and beaded, they clatter against the steel.

We pull into the driveway, a pile of packed sand. Vacant cabins are scattered about in varying states of disrepair, but the main house has recently been painted lemon. Its window hosts a nativity scene: Mary, baby Jesus, and an assorted cast of winged or bearded crew. As we tramp through the sand toward its front door, a woman steps out. She is wearing a long red cardigan over a leopard-patterned blouse and a rosary of heart-shaped beads. Her hair is poodled and her cheeks are Pepto-pink. This must be the tree’s keeper, Estella Palacios Garcia. She appears to be eighty years old.

“Did you listen to my tree?” she demands, hand on hip. “Go on. Listen. I wait inside my chapel.”

We retreat. Fake floral bouquets sprout from the dirt, their petals bleached by the sun. A slip of blue construction paper is nailed to a nearby post: PLEASE NO WRITE ON MIRACLE TREE. I WILL FILE CHARGES FOR DAMAGES.

Though toweringly high, the tree is no thicker than me. Its bark is smooth as parchment and the color of ochre save for the chest-level region, where years of adoring fingers have oiled it orange. Its branches don’t begin until eight feet up, rendering it strangely huggable. I press my ear against the trunk and—to my great surprise—hear the sound of trickling water. It’s no louder than a meditative fountain at a yoga studio, but still. Trickling water. I gasp and pull away.

“Do you hear that?”

“There’s a little river in it!” Greg exclaims.

We circle round and round the tree, listening at different levels. The volume fluctuates, but the sound is unmistakable. Trickling water. I rap the trunk with my knuckles. It feels hollow inside. Do all trees sound like this? Greg and I confer, but neither of us has listened to any lately.

We step inside the chapel, a small trailer adjacent to the house. Sunlight streams through the windows, the only light except for the glowing grill of an electric heater. Estella sits in a chair like an oracle, her hands neatly folded in her lap.

“We heard water,” I announce.

“The tree wants to tell you something but needs more time. Come back when is not so cold.”

Like all South Texans, the tree refuses to function in inclement weather.

“What do other people hear?” Greg asks.

“Oh, many thing. Sometime you hear a heartbeat. Sometime you hear a door close and then a-knocking, and you know what it is? It is Jesus knocking on the door.”

As many Tejanos do, I grew up Catholic, and—despite my wildly divergent views on everything from abortion to the Vatican—I still claim to be one. It’s practically cultural heritage. Yet I shy away from conversations about religion, as they haunt me about all the internal work I must do before I can develop a spiritual mestizaje of my own.4 So instead of engaging Estella directly about her faith, I study it upon the walls, where colored pushpins impale hundreds of photographs. Graduates wearing caps and gowns, brides kissing grooms, mothers kissing babies, elderly couples cumbia-dancing across a ballroom floor. Half a dozen driver’s licenses align in a row.

“Miracles!” she interjects, catching my glimpse. “A man’s wife, she have cancer in California and I send her oil and a picture of my tree and five month later she is healed. The cancer, it go away. Thanks be Jes—”

Some photographs are accompanied by handwritten testimonios, either tucked beneath the photographs or displayed inside the picture frames propped on the floor. In English, Spanish, and Spanglish, these letters either entreat the tree for mercy or express gratitude for granting it. One is accompanied by a newspaper clipping: I am seeking justice for my son that was massacred at this prison. They send him home in pieces. May They Close All This Private Prisons! Thank you Lord, Santos Cardenas.

“—and this woman from Mexico, she is sick, very-very sick of her lung, and she comes to me and asks what do I do so it go away and I say you stand against my tree for thirty minute and you pray-pray-pray to God . . .”

One wall features photos of men in military uniform, young men, barely twenty, speckled with medals and acne. Their gazes are unsettling, emitting a blend of macho pride and fear.

“—and she did and she is healed. A specialista of the lung, he say the cancer is gone! Erase.”

She stares at us in wonder.

Estella’s isn’t the first miracle tree to spring up in the borderlands. In 1966, Time wrote about a thirty-foot acacia tree in La Feria that mysteriously began secreting a tea-colored liquid from its knothole. Neighbors started dropping by to touch the water, rub it on their bodies, and drink it. Miracles quickly followed. A blind woman’s vision returned after the water was poured in her eyes; open sores disappeared from a child’s face. Pilgrims descended upon the tree by the hundreds. Never mind that a string of experts said the water was sap: the believers deemed it holy.

Thirty years later, La Virgen de Guadalupe appeared in the bark of a cottonwood tree on a median in downtown Brownsville. Crowds lined up for blocks to kiss it. Next came the “crying tree” of Rio Grande City. A matriarch named Leonisia Garcia used to spend her afternoons beneath her acacia tree painting cascarones5 to sell at Easter. She collapsed there from a heart attack in her ninety-second year, and the day after her funeral her family noticed foamy froth dripping from the tree branches. “We feel like that tree is now missing her,” her daughter, Mary Lou Sanders, told the Dallas Morning News. “It is something I cannot explain.” Scientists could: it was a spittlebug nest. But to the hundreds of onlookers who gathered each morning clutching Styrofoam cups, it was “miracle ice.” One mother from Roma brought in her son in a wheelchair, collected a few drops, dipped in a reverent finger, and drew crosses upon his forehead. “God made a miracle to save his life,” she told the newspaper. “I know he is going to make another miracle and he’s going to lift my son out of that wheelchair.”

When I ask Estella about these other trees, she waves a hand in dismissal. Shams, all of them. She predicted her tree’s power before she even planted it. One night six years ago, she read a passage in the Bible about Jesus healing the sick with the leaves of an olive tree. When she awoke the next morning, she decided: “God, I go to the Valley to find this tree.”

At a nursery near Brownsville, she told a gardener that she wished to buy a Monte de los Olivos tree from the Holy Land. What luck, he said: they had one in stock, “all the way from Jerusalem,” for three dollars.

“When I buy, it is this high,” she says, holding her hand a foot off the ground. “And I pray to God, ‘Send me miracles, send me people to heal their cancer, to heal their tumors,’ and I tell the tree and I plant it. It grow and grow and grow and then when is like this,” she raises her hand another foot, “I listen and it sound like running water.”

She waited until the tree was two years old (“so is not so skinny”) before she spread word of its powers. Her first two visitors were a man and a woman who prayed around the tree until God appeared. The man ran away in fright, but the woman continued praying. “She stay and pray and is healed.”

Soon, people were traveling across Texas to visit her tree. After a Mexican television station aired a special about it, pilgrims even crossed the border in tour buses. I ask how many had visited in all. One thousand? Two thousand?

“Fifty,” she says.

“Fifty thousand?”

Blinking sassily, she continues on for the better part of an hour. A miracle lurks behind every handwritten letter propped upon her floor, behind every photograph pinned upon her wall, behind every rosary woven through the chain links of her fence, and she wants to share them all. And at that moment, I want to believe them. I want to be that six-year-old upon Tío Valentin’s knee again, the girl who lit candles before Mass each Sunday and prayed to someone she thought could hear. For a moment, my ability to rebuild a life in South Texas after a fifteen-year absence seems contingent upon such belief.

I glance over at Greg. If he believes in talking trees, I can believe in talking trees.

His posture spells rapture. He sits perfectly erect in his hard metal chair, his hands folded inside his lap, a smile upon his lips. But his eyes have gone glazy. His head leans forward, then pitches back.

Metaphorically rising from my tío’s knee, I thank Estella for her time. Greg stirs awake and follows suit. As we approach the truck, a caravan of eighteen-wheelers hurdle past, each one hauling an unmarked tank. Dust clouds swirl behind them.

“Where are they going?” I ask. We are miles from the nearest highway.

“Aye,” Estella says and shudders. “They dump their tank.”

“Dump? Where?”

“Across my street.”

There doesn’t appear to be anything across her street but a grove of mesquite, yet Estella says a waste pit lurks behind the trees where trailers dump their tanks late at night.

“How do you know they are dumping?”

“I hear them!” she says. “The city come to test my water and they say is no good. All these ranches, the water is no good.”

Who came? When? What did they determine? My inner reporter demands three-ring binders bulging with certifiable facts. But Estella cannot supply them. She knows only that her well has been contaminated for fourteen years by something so strong, not even her miracle tree can cure it. She must buy bottled water from Premont. And since “the city” has been no help, she built a shrine to beseech the spirits instead.

We exit her property, my thoughts ablaze. Even if no one is outright dumping here, the area is littered with natural gas wells. Their reputation for tarnishing water is memorialized in the documentary Gasland, which shows families lighting their drinking water on fire as it pours out of the tap. We continue down the road and, after a time, come upon a clearing. An open gate reveals a slender dirt path. Beyond it, a herd of bulldozers paw the earth. As we idle on the side of the road, wondering what to do, an eighteen-wheeler with an unmarked tank pulls up behind us. We watch it enter the gate and vanish inside the brush.

1. Throughout the seventies, people traveled to Tía Eva’s chapel from all around, Santa says. Eventually, however, she started getting ill from handling so many spirits and had to stand in a pan of water while conducting her healings to avert the negative energy. Then the Catholic church accused her of witchcraft, so she closed the chapel altogether. Though Tía Eva has since passed, she lives on in the mystical elements of Santa’s work.

2. An evangelical Christian, Santa’s father believed the olive oil was holy because it had been perched atop the radio when it broadcast a service by the Galvan Revival Church. He deemed the miracle tree sacrilegious, though, so Santa had to use its leaf discreetly.

3. Nope, not fried chicken, but chicken-fried chicken. Similar to its cousin, chicken-fried steak, it is a chicken breast pounded thin, heavily battered and deep-fried, then drowned in white or brown gravy and served with a heap of mashed potatoes and a slice of Texas toast (that is, one that’s bigger than your plate).

4. Like many illuminating ideas in border studies, “spiritual mestizaje” was first theorized by the writer Gloria Anzaldúa. The scholar Theresa Delgadillo defines it as the “transformative renewal of one’s relationship to the sacred” as a way of defying oppression via “alternative visions of spirituality.” Through this lens, Estella’s shrine can be viewed as an act of resistance.

5. Cascarones are colorfully painted eggshells filled with confetti that get hidden in the backyard and then cracked on unsuspecting heads on Easter Sunday sometime after the barbacoa is served but before the poker games start.