CHAPTER 4

Understanding Earthen Plasters: A Closer Look at Their Components

THE SUCCESS OF AN EARTHEN PLASTER on a straw bale or other natural home depends on many factors.As pointed out in Chapter 3, the design of a home is crucial to its success, as is its construction. Properly preparing the walls is essential as well.

The durability of an earthen plaster also depends on the quality of the mix. The quality of the mix, in turn, is determined by the use of proper materials in proper ratios. As we have pointed out earlier, each building site is characterized by unique soil conditions, meaning distinctive types of clay, silt, sand, and aggregate in proportions unique to the location. Because of this, recipes for plaster change from one building site to the next.

How do you know what recipe will work for your project? Fact is you don’t.You have to determine your own recipe on a case-by-case basis.

Don’t be dismayed, however; simple tests and a little experimentation with potential mixes will allow you to determine a suitable recipe. Before you can proceed to this stage, however, you need to know more about the components of plaster.

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE A PLASTER’S PERFORMANCE

Design of the house

Construction and preparation of the wall

Quality of the plaster mix

How plasters are mixed

How plasters are applied

How plasters are maintained

In this chapter, we’ll describe the basic components of an earthen plaster and explain the functions each one performs. We’ll examine clay and clay-soils, sand, fiber, and silt, addressing the qualities you’ll be looking for in each.We’ll also discuss natural additives — substances added to plaster to enhance its workability, application, and performance.

This discussion will provide information that will come in handy when the time comes to make your own plasters.As we’ve mentioned earlier in the book, our goal is to provide you with a solid understanding of plaster and its components, enabling you to create recipes that work well at your site.

COMPONENTS OF EARTHEN PLASTERS

Clay-rich soil

Sand

Fiber (usually straw)

Water

Natural additives

What are the Primary ingredients of an Earthen Plaster?

The three primary components of earthen plasters are clay-dirt, sand, and fiber. Many mudders augment their plasters by mixing in various natural additives such as cooked flour paste or manure. Water, of course, is used to make the mix workable. Water evaporates from the plaster after application, leaving a hard, durable wall finish. Understanding the function of each of the main components, as well as the function of the various additives, will help you create a plaster mix that works well on your home, providing years of unrivaled beauty and protection.

Clay: The Binding Agent of an Earthen Plaster

In Chapter 2, you learned that all plasters must have a binding agent. In earthen plasters, clay serves this purpose.

WHAT IS CLAY? Clay is a material consisting of extremely fine particles. But like many things in our world, clay is a fairly complex substance.You could spend a lifetime trying to understand this diverse and complicated material.

Most clays consist of hydrous aluminum silicates — which means they contain aluminum silicate with associated water molecules. However, there is considerable chemical variation among clays.These chemical differences result in variation in the properties of different clay “species.”

CLAY: IT’S EVERYWHERE!

One reason earthen buildings and earthen plasters have been widely used for so long by so many people — and are still in use today — is that clay is abundant and usually found in sufficient quantities in the subsoil in most parts of the world.

CLAY IS A BINDING AGENT AND WATER PROTECTOR IN EARTHEN PLASTERS. Being rather sticky, clay binds to the sand and straw in earthen plaster, and thus holds the mix together. Clay also binds the plaster to walls.

As we noted in Chapter 2, clay molecules often consist of microscopic plates, known as platelets. Water in clay forms a chemical bridge between them, allowing the platelets to bond to one another (see Fig. 2-10). According to soil scientists, the bonding of water between clay platelets retards the movement of free water molecules deeper into the clay. As a result, when clay is exposed to water, it self-seals, creating a water-resistant surface.This helps prevent liquid moisture from penetrating a wall and damaging its interior. Remember, when we say that clay is “water resistant,” we’re not saying it is waterproof like a sheet of plastic or a rubber rain coat. Rather, clay resists water penetration. When the surface layer of an earthen plaster becomes damp, it retards any further water penetration.Therefore we use the terms water resistant and water protective when we talk about clay. At the same time, however, clay allows water vapor to pass through. In addition, clay also acts as a preservative, by wicking water away from straw. It also dries quickly, which helps reduce moisture migration into walls, and prevents damage to the interior components of the wall. (The properties are explained in detail in Chapter 2.)

WHERE DOES CLAY COME FROM? Clay consists of fine particles of aluminum silicate combined with natural minerals — some of which color the clays they’re in. Clays are found all over the world and come from many different sources. They’re often derived from the slow weathering of feldspar, a type of igneous rock which is one of the most common of all minerals within the Earth’ s crust. Clays are also derived from several other minerals, such as mica.

COHESION OR STICKINESS. Clays exhibit a property soil scientists call cohesion. We call it stickiness or adhesiveness — the property which makes clay an excellent binder. Scientists attribute the cohesiveness of clay to the chemical attraction formed between the clay particles and water molecules held between the platelets. (For those with a background in chemistry, it is the hydrogen bonds between clay platelets and water that provide the cohesiveness.)

As you work with various clays, you will find that some are more cohesive than others. Kaolin clays, for instance, are much less cohesive than the smectities, a large group of silicate clays. (Note, however, just because a clay is highly cohesive doesn’t mean that it is suitable for a clay plaster. Bentonite, for instance, is cohesive, but is highly expansive and thus not suitable for an earthen plaster.)

PLASTICITY OR PLIABILITY. Clay also exhibits a property soil scientists call plasticity or pliability. Plasticity means that clay is capable of being shaped or molded. This property is most likely due to the plate-like nature of clay particles combined with the lubricating and binding influence of water between the platelets.

Clay is pliable only when wet. However, its plasticity varies over a range of moisture levels.When a little moisture is added, clay becomes slightly plastic.As more is added, it becomes very plastic and quite workable. When too wet, it loses its plasticity. You’ll be able to use this knowledge as you work with clay plasters.

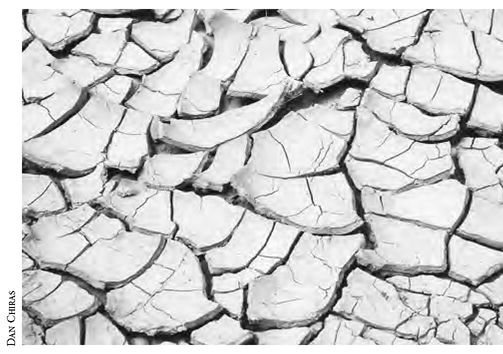

4-1: Clay like this mud along the Colorado River shrinks when it dries, which leads to cracking. Too much clay in an earthen plaster will cause excessive cracking.

CLAY EXPANDS WHEN WET. Clay platelets bind to water molecules. This, in turn, causes clay to expand.When clay dries, it shrinks and tends to crack. This property allows for easy identification in the field. Dry clay also tends to be hard and brittle. However, in a plaster in combination with other components, dried clay retains its superior bond strength — meaning it functions as an excellent binder. Sand and straw in the clay plaster help eliminate cracking.

CLAY IS SLIPPERY. Anyone who’s ever handled clay knows that this is a rather slippery material.This distinguishing feature, useful for identifying clay deposits in the field, results from the fact that the flat platelets slide over one another like plates of glass with water between them.

THE COLORFUL WORLD OF CLAY. As Michael Smith writes in his book, The Cobber’s Companion,“Clay takes on a rainbow of colors.” Mineral oxides are responsible for the variety of colors in clay , a gift from the Earth that Mudders have long made use of in finish coats and clay paints to give walls a stunning appearance.

LOCATING CLAY

When driving along highways, you may be able to spot clay deposits by their rich and varied colors. (Although colored soil does not always mean it’s clay!) Some clay is brick red. (In fact, that’s where red bricks get their color!) Some clay is kind of yellowish, a color often referred to as ochre; others are brown or bluish-gray. If you start looking around, especially in the painted deserts of the Southwest, you’ll be treated to a rainbow of clay colors: green, mauve, rose, white, yellow, brown, and many other hues. It is truly one of nature’s marvels.

Clay is found along roadways where subsoil has been exposed by bulldozers. It is commonly found around wetlands, although digging here is not recommended for ecological reasons. Check sections of dirt roads that always get slippery after rainstorms, and the places where puddles appear first and disappear last. They appear first and disappear last because clay prevents water from percolating downward. Puddles only disappear when the water evaporates.

YOUR MAIN SOURCE OF CLAY: THE SUBSOIL. Clay is widely dispersed on Earth. It is found in both the topsoil and subsoil. Clays are also found in deep deposits in the Earth’s crust, on the floors of lakes and oceans, in certain glacial deposits, in desert basins, river deltas, in windblown deposits (called loess), and in a number of less significant areas.

4-2: Subsoil usually contains higher levels of clay and lower levels of unwanted organic matter than topsoil. It is, therefore, usually the best source of material suitable for earthen plasters.

Although clay is present in the topsoil in most areas, greater concentrations usually occur in the subsoil. Moreover, topsoil contains organic matter that has no place in an earthen plaster. Organic matter consists of live plants, roots, and bits and pieces of plants and dead animals, such as earth-worms and insects, in various stages of decomposition. Organic matter may decompose in a plaster and has little binding capacity. As a result, it can compromise the integrity of an earthen plaster. Organic debris in a plaster also makes application more difficult. Subsoil generally has a much lower content of organic material. The occasional roots that may occur in the subsoil can be screened out or removed by hand.

Because of these factors, most mudders use subsoil to make their plaster, the layer of dirt beneath the topsoil.The only exception is in desert climates. Here it is often possible to collect clay on the surface as there is little, if any, topsoil.

Because you may be using topsoil or subsoil to make plaster, we’ll frequently refer to your starting material as clay-rich dirt, clay-rich soil, or just plain dirt. Note, too, that clay-rich dirt contains other things as well that are important to a plaster — for example, some silt and sand (both described shortly).

HOW MUCH CLAY IS IN YOUR SUBSOIL? Determining the amount of clay in soil requires a few simple tests. Be sure to run these tests long before the plastering begins, preferably while you’re in the design phase of a project. Don’t wait till the last minute. If your soil flunks the tests, you’ll need to augment it or import a clay-rich dirt from another site. If your plaster crew is ready to go and your plaster mix needs enhancement, you’ll end up wasting their time while you are trying to “fix” the dirt. And time, of course, can create a monetary penalty on building sites. If your dirt “passes” all the tests described below, it probably has a decent clay content.

So how do we go about testing a site for the presence of clay?

GRAB A HANDFUL. First dig down through the topsoil on your site; it’s usually dark and fairly soft. Beneath the topsoil is the subsoil, a lighter-colored material that is usually much harder and more difficult to dig through. Once you reach the subsoil, scoop some loosened dirt into your hand. If it is moist, compress the material in your hand, then squeeze it tightly. If the subsoil is dry, slightly moisten it, then squeeze. If the dirt contains clay, it should bind together and hold its form. The better it “holds together,” the higher the clay content .

THE WORM TEST. Next, perform a simple worm test — so named because you’ll be making a pencil-thick worm out of earth.We’ll call it a “dirt worm” so you won’t get confused with the real thing, the annelid earthworm.

First put a little of your dirt in your hands. If it is dry, spit into the dirt or moisten it by sprinkling water on it, then mix it in your fingers. When the sample is thoroughly mixed, roll it back and forth to create a pencil-thick dirt worm. As you roll the moistened soil around, you’ll begin to get a feel for the mix. Pick it up. Does your dirt worm remain intact? If so, your clay content is probably sufficient. If it falls apart, you may need to add more water and if that doesn’t work you may need to supplement your subsoil — that is, add some more clay.

4-3: The Worm Test

GET THE FEEL FOR IT. Next, take a larger amount of dirt into your hand and wet it down. Get it moist. Play with it a bit. Pull it apart. Roll it into a ball and make a patty cake. How sticky does it feel? If the dirt isn’t sticky, you may need more water; wet it slightly and work it again. If it still isn’t cohesive, don’t despair; you can add some powdered clay, flour paste, manure, or other natural additives to increase its cohesiveness.

JAR TEST. This allows you to determine the proportions of clay, silt, and sand in your dirt.

First, fill a clear glass jar one-third full with dirt. A one-quart or one-pint mason jar (or any empty pickle jar) will work. Pick out small rocks and organic matter, such as roots. Break up any clumps in the subsoil. If they are difficult to crush, try adding a little water and letting them soak for a few hours.

4-4 (a) (b): The jar test. (a) Soil to be tested is placed in a jar. Water is added and the jar is covered and shaken. (b) After vigorous shaking, the jar is placed on a flat surface and the materials begin to settle out. Measuring the layers tells you how much sand, silt, and clay are in your soil.

Next, add water, filling the jar two-thirds of the way to the top. If you add a teaspoon of salt to the mix, it will speed up the deposition of clay, which as you’ll soon see is the slow poke in the group. Next, place the lid on the jar and screw it on tightly. Shake the jar vigorously for a minute or two over a sink or outside in case it leaks. Alternatively, if you have an old blender, you can dump the mix into the machine and let it do the work. Let it run until the test sample is thoroughly mixed. When thoroughly mixed, pour the contents of the blender into a jar.

After shaking or blending, place the jar on a flat, level surface.The components of the mix will begin to settle out. The largest, heaviest particles in the dirt (pebbles and coarse sand) fall to the bottom within seconds.After about three seconds, mark the side of the jar to indicate the top of the sand and pebble layer. Finer sand particles settle out next, then silt: both should settle out within ten to fifteen minutes. However, the line between silt and fine sand is sometimes difficult to distinguish. Michael Smith, a veteran cob builder, draws the line between silt and sand when he can no longer see individual particles.

Clay particles, which are even finer than silt, settle out last. They’re so fine, in fact, that they may remain suspended in solution for several days. If the water in the jar turns clear quickly, that’s a sign that there’s not much clay in your dirt. If it remains cloudy or opaque after the sand and silt have settled out, you’re in luck: there’s clay in your subsoil. You may also note that some organic matter may be floating on the surface of the water; it won’t cause any problems. After the clay settles, measure the thickness of each layer to determine the relative proportions of clay, silt, and sand.

The jar test may take a few days, or even a week, to complete — and that’s another reason why you should test your soil well in advance of plastering.The jar test provides a reasonably good estimate of how much clay, silt, and sand are in a dirt sample. However, because clay expands when wet, you can achieve a more accurate measurement by drying the sample.After the clay settles out, scoop out the clean water on top of it, then let the jar sit with the top off. Put it out in the sun to accelerate the drying.When dried, you can make a more accurate measurement of the clay content and thus more precisely determine the ratio of clay to silt and sand.

An earthen plaster soil should contain 5% to 12% pure clay, according to Gernot Minke, author of Earth Construction Handbook and a professor of architecture as well as the director of the Building Research Institute of the University of Kassel.The ratios of clay to sand to silt — and the characteristics of the clay — will determine what you need to do, if anything, to make your soil suitable for plaster.

TESTING THE SOIL AT SEVERAL LOCATIONS. When performing tests, you may want (or need) to sample subsoil from several locations on your building site. It is usually more convenient and more economical to use dirt that’s been excavated for a foundation or a basement, rather than excavating and transporting suitable dirt from other locations. However, you may find a better soil thirty feet away from the foundation excavation. Subsoils can vary quite considerably within a relatively small distances. Finding a clay-rich subsoil may require you to dig a couple of test holes first. By testing several locations at a building site, you increase your options. It’s great to have several choices.

BEYOND RATIOS

Ratios provide you with important information — notably, how much clay, sand, and silt are in your starting material. This will help you decide which components need to be added to your mix to enhance its performance. However, ratios do not determine the quality of various components of a plaster mix, most notably the clay. Clays vary chemically and chemical differences result in differences in properties: pliability, cohesiveness, and so on. Playing around with your soil, as described earlier, and experimenting with it are both critical in determining the performance of soil in plasters.

TAKE TIME TO FEEL THE PLASTER

If you attend a workshop on plastering, be sure to take some time to feel the various components. Run your hands through the soil that is going to be used to make plaster. Moisten it, roll it around in your hands, and assess its stickiness. Do the same for the various plaster mixes. Close your eyes and really concentrate on the feel of things. That way, when you get home you will have a good sense of what your plaster should be like.

WHAT DO YOU DO IF YOUR SOIL DOESN’T CONTAIN ENOUGH CLAY? If your dirt is clay-poor, and therefore lacks cohesion and other properties needed for a successful plaster, you can amend it. One option is to mix in a higher-clay-content dirt from another source, preferably one nearby. If you don’t have a source, you can always augment the subsoil on your site by purchasing high-clay content dirt from a local supplier. Overburden (the dirt on top of a gravel deposit) may be suitable: it can be obtained from local gravel pits and is usually quite inexpensive. Excess dirt from nearby construction sites may also be suitable. Be sure to test any soil you are considering for use in plasters. However, you’ll quickly discover that while dirt is cheap, having it hauled to your site is not. But even so, for a few hundred dollars, you can often obtain enough clay-rich subsoil for a complete project.

INCREASING THE ADHESIVENESS OF A PLASTER MIX: OPTIONS

1. Blend subsoil with a higher clay content subsoil

2. Extract clay from subsoil and add it to your mix

3. Add supplements such as manure and flour paste

4. Add bagged clay

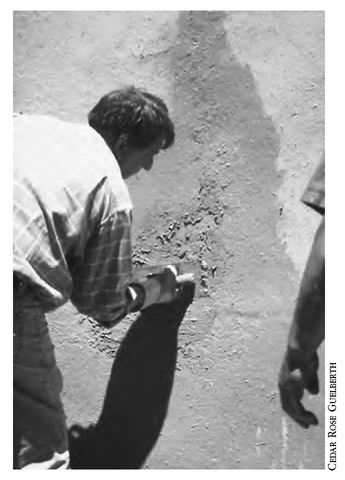

4-5: Workers apply an earthen plaster to St. Francis Church. Their soil contained a suitable ratio of clay, silt, and sand and could be used as is with water and straw added.

You can also amend soil by adding bagged (dry, powdered) clay, such as kaolin, which is available at local pottery supply stores or other outlets. Flour paste and manure added to plaster also increases the stickiness and pliability of a subsoil — essentially reducing the amount of clay you need in your mix. We’ll talk more about these options a little later in this chapter and in Chapter 6.

A more labor-intensive but more environmentally benign way of securing additional pure clay is to extract it directly from some of the subsoil on your site. Extracted clay is added to your subsoil to increase its content. Harvesting clay from dirt is relatively simple: To begin, screen clay dirt over a tarp, wheel barrow, large tub, or garbage can to remove rocks.A 1/2-inch hardware cloth (screen) works fine. Break up chunks of clay with your hands by rubbing them against the screen.

Fill a tub or trash can one-third full of water, then add screened soil while stirring with a hoe or mixing with a paddle mixer. Continue to mix while adding dirt to prevent clumping.

After the dirt has been thoroughly mixed and clumps of clay have been broken up, give it a few minutes to allow sand and aggregate to settle.You can now begin to pour off or scoop out the material that forms on the top. Called clay slip, it consists of clay and some silt and can be added to your plaster mix to increase its clay content.

If you have more time, let the mixture settle for a day or two, remove the water on top, then carefully scoop out the layer of clay that forms on the top. Alternatively, you can wait until the mixture dries out, then remove the clay from the top.

If you need to substantially increase the clay content of your soil, locate a local source of a higher clay-content soil, and use it either to mix into your existing soil or to use in place of existing soil. Alternatively, you can add some dry, powdered (bagged) clay to increase the clay content of your soil.You may also be able to increase the adhesiveness of your existing soil by using natural additives (such as flour paste and manure).

Sand: Structural Strength

Sand consists of tiny mineral granules of rock, its parent material. Predominantly composed of quartz, or silicon dioxide, sand is a chemically non-reactive substance.

SIZE, SHAPE, AND HARDNESS. If you’ve spent much time on beaches, along rivers, lakes, dunes, and the world’s oceans, you know that sand varies in color and grain size: some sands are very fine, others are quite coarse. In fact, sand grains vary from 0.05 mm to 2 mm in diameter.

Grains of sand also vary in shape: Some are quite angular and sharp; others, like beach sand, are often smooth and round, having been polished by waves for centuries. Dune sand tends to be fine-grained and smooth, after having been polished when the wind blows sand grains over one another. Sand also varies in hardness: some sand grains like quartz sands are very hard; others are less so.

WHY ADD SAND TO A PLASTER? In an earthen plaster, sand provides structure, strength, and bulk. In a plaster, sand particles are bound together by clay. On its own, clay does not create the structure required for a good plaster. It’s not terribly stable, but rather pliable. Sand, on the other hand, is geometrically stable. It transfers this property to an earthen plaster. Combined, clay and sand make a strong and stable material.

4-6: To extract clay from subsoil, fill a tub or durable garbage can one-third with water, add screened soil, and mix thoroughly with a hoe or paddle mixer. Clay will be suspended in the water on top. Sand and aggregate will settle to the bottom quickly.

OUT OF THE SAND BOX

Buyer beware! Sand for sand boxes often contains a lot of silt and dirt. It must, therefore, be washed before you can use it. It also tends to be too coarse for finish plasters. Instead, purchase washed masonry sand from a local source.

Sand provides other benefits as well. For example, it doesn’t expand or contract when it is wet, as clay does. This helps stabilize an earthen plaster, preventing it from cracking. Sand is also water insoluble: it won’t dissolve away. It is also chemically non-reactive: it won’t react with clay or other components of an earthen plaster.

USING WHAT’S AVAILABLE OR ADDING SAND. Because sand occurs naturally in many subsoils, it may not be necessary to add any sand at all to your dirt to make plaster. If there’s not enough sand in your subsoil, however, you will need to add some.

Sand can be obtained from a number of different sources. You can, for example, harvest it along nearby river banks or at local beaches. (Beach sand containing salt may cause white blotches to form on the wall, as the salts migrate out of the plaster, so be sure to wash it first.) If natural sources aren’t available, you can purchase sand by the truckload from local sand or gravel pits. Either way, local sand should generally be run through an 1/8-inch metal screen to remove small stones and organic debris.

If you elect to purchase sand from a local source, such as a gravel pit or sand pit, we recommend buying washed masonry sand, which can be purchased in dump truck quantities. Masonry sand is also relatively inexpensive. Washed masonry sand is clean (free of dirt or silt) and works well in earthen plasters and generally will only need to be screened if it is used for finish plaster (final coat).

4-7: Carole Crews and her kids sift beach sand for use in plasters. If you collect sand from naturally occurring deposits, especially beaches, we suggest you rinse it before use to prevent cloudy salt deposits which can migrate to the surface of your finish.

Washed masonry sand is often suitable for finish plasters. If you want a finer finish coat, silica sand can be used, though this is not necessary.As a general rule, coarser sands are used for the first layers of plaster, and finer sand for finish coats.

Of the various sources of sand, the most expensive is bagged sand, which is available at many building supply stores. Be careful not to purchase play sand or any similar product, as they often contain a lot of dirt and silt.

Fiber: Providing Tensile Strength and Reinforcement

Fiber is the third ingredient of plaster. Dry straw, hemp fiber, cattails, and animal hair (such as wool) are all suitable. Horse manure and coconut and sisal fibers can be used as well. Straw is the most commonly used fiber because it is widely available, easy to work with, effective, and relatively inexpensive.

WHY ADD FIBER? Fiber forms a reinforcing meshwork in plasters, which helps to hold the mix together when it is wet as well as dry. Fiber also provides some flexibility in a dried plaster. As you may recall, when clay dries it shrinks and tends to crack. This cracking can be countered by fiber, as well as sand. If your mix is good, you should have little, if any, cracking.

DRY, MOLD-FREE FIBER: A MUST. The fiber used in plasters must be clean (not moldy) and dry. When ordering straw, a commonly used material for plasters, be sure it hasn’t gotten wet. Open up a few bales and look for discoloration — sure evidence of mold. Mold usually appears dark, but is sometimes white or other colors (yellow or gray).A clean, dry straw should have a golden color throughout.You can also smell the straw to see if you can detect the odors given off by mold. You can test bales with a moisture meter prior to purchasing or use: high moisture levels may indicate the presence of mold.

When the straw is delivered to your site, store it in a dry place off the ground. If you come across any wet or discolored straw, dump it in your compost pile or use it to mulch your garden.

WHAT SIZE FIBER? Add fiber of different lengths to earthen plasters. Variations in length of fiber creates a stronger material.

In the first two layers of plaster (the base coat), larger fibers, measuring 4 – 8 inches (5 – 10 cm), are appropriate, but you should also throw in some 1- to 2-inch (2.5 – 5 cm) fibers.The final or finish coat does not require large-diameter or long fibers.They can compromise the integrity of an exterior finish coat and may lead to surface deterioration.

VARIETY IS THE SPICE OF LIFE

Add fiber of different lengths to earthen plasters. Variations in length and type of fiber (straw, cattails, wool, etc.) create a stronger material.

If you like the appearance and want to add straw to a finish coat, be sure to chop it to lengths of 1 – 2 inches (2.5 – 5 cm). While eliminating straw in the final exterior coat is recommended, you may want to add other forms of fiber. Adding manure, for example, provides microfibers that improve the quality of a finish coat, as do the small fibers of cattail fluff and wool. (For more on fibers in plasters, see Chapter 6.)

ACQUIRING STRAW FOR PLASTER. Because straw is the most widely used fiber for earthen plasters, we’ll focus our discussion on this product. Bear in mind, though, that other fibers work well, too.

Straw for plaster can be acquired from several sources. When building straw bale homes, you will find that straw of varying lengths accumulates around your pile of bales and along the walls of your home. Loose straw will be especially abundant after walls have been shaped and trimmed. Splitting bales produces loose straw, too.We recommend that you gather up loose straw as construction proceeds. Make sure it is clean (that is, free of debris) and kept dry. Store it under tarps or in burlap or other bags. If possible, store indoors. Do not store it in closed plastic bags; moisture can accumulate in such instances. Gathering straw before it gets wet or dirty not only provides a source of fiber for plasters, it helps to reduce potential fire danger.

CHOPPING STRAW. For a successful plaster, most straw needs to be chopped into smaller lengths. Occasionally, you’ll find straw bales containing short strands. Many times this is an indicator of poor-quality straw bales.Although they’re not suitable for building walls, they can be great for making plasters as long as the straw is clean and dry.

There are a number of ways to chop straw. Many people throw straw into a clean garbage can, then have at it with a weed eater or weed whacker. If you have access to a leaf and grass mulcher, straw can be chopped this way as well. Straw can also be shredded with a chain saw.

Some mudders grate straw on a ¼-inch wire screen or metal lath.To do this, grab a handful of straw, then rub it along the surface of the wire. Be sure to wear gloves to protect your hands. Smaller pieces will fall through the grate. You can even grate straw successfully over diamond lath draped over a cardboard box. (Neither process is very fast and therefore not practical for larger projects.)

OTHER SOURCES OF FIBER. Natural fibers can be collected from a host of other sources. Cattails, for instance, are a great source of fiber for plasters, especially finish plasters. They’re collected in the fall when the cattail heads are brown and ready to let loose their small fluffy fibers.

Wool and hemp fibers are also good for plasters. Raw wool can be teased apart and cut into more manageable lengths with a pair of sharp scissors. Manure from a variety of animals works well, too. Fresh horse and cow manure can be collected from nearby farms and transported to your site. Horse manure is a better source of fibers whereas cow manure is a better source of enzymes that improve the adhesive qualities of a plaster. However, either one will do.

Additives: Improving the Durability and Function of Plasters

Most earthen plasters consist of clay-rich dirt, sand, and fiber mixed with water.As noted earlier, additives are often used to improve the quality of a plaster: they add strength and produce a more cohesive, durable plaster. Whether you add them to a finish coat or all coats depends on the quality of your raw materials. If you’re starting with sandy or silty dirt with low clay content which isn’t very sticky, you may need to supplement all mixes, from the base coat to the finish coat.

Some of the most common additives are cooked flour paste, manure, cactus juice, casein (milk protein), and various natural oils such as linseed oil and canola oil. Some other additives include alum, natural glues, gum arabic, kelp, lime, and powdered milk. Salt, stearate, tallow, tannin, leaves and bark of certain trees, and xantham gum have also been used. Ox blood has been used in some cultures and is still used in traditional cultures for adobe floors as well as plasters; the protein in the blood is believed to create a more durable finish.

From the list of additives shown in sidebar, you can see that there are many ways to achieve the plaster qualities you need. There are also many additives we haven’t included, which are unique to local cultures and determined by local availability.We’ll focus on the main additives in this book to keep things simple and help build your understanding of plasters.

FLOUR PASTE. Cooked flour paste is an easy-to-make, readily available material made from water and flour. In a plaster, flour paste serves as a binding agent and a hardener.That is, it makes plaster more adhesive when wet. It also results in a harder, more durable, and dust-free finish when dry. Flour paste also makes plaster smoother and improves its “workability” — that is, how well it goes on straw bale and earthen walls. (We’ll describe how flour paste is made in Chapter 6.)

NATURAL ADDITIVES

The following additives increase the workability, durability, and water resistance of an earthen plaster, and can minimize dusting:

• Cactus juice

• Cooked flour paste

• Casein or milk powder

• Oils

• Alum

• Kelp

• Lime

• Gum arabic

These additives increase the pliability and strength of plasters by adding fiber:

• Animal hair

• Cellulose (newsprint)

• Cattails

• Cow manure

• Horse manure

• Leaves and bark of certain trees

Some people are concerned about insects and rodents eating their walls or mold forming on them. However, the amount of flour paste added to plaster is so minimal it does not attract critters or mold. Cooked flour paste has been used successfully for centuries in a number of products such as wall paper glue and plasters — without molding.

MANURE. Manure is also an effective additive: it serves as binding agent and gives plaster more body. The binding properties of manure most likely come from enzymes and proteins in the material, which make plaster stickier when wet and more water-resistant when dry. Manure also contains small fibers that strengthen a plaster and reduce cracking and water erosion.

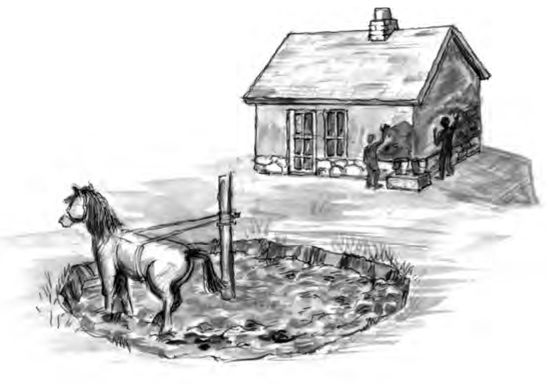

4-8: Historically, horses tethered to a center pole were used to mix plasters. Manure dropped into the plaster improved the quality of the finish product. Modern plasterers often add manure for the same reason.

Manure probably first began to be added to plaster by accident. In earlier days, draft animals were often used to mix plaster. Tethered to a center pole, horses were driven around and around over a plaster mix: their hooves mixed the plaster and their intestinal tracts supplied free additives. Early mudders liked the results.

Many different types of manure have been tried over the course of time, each with its own unique benefits. Horse manure, for instance, has a high microfiber content. Cow manure has more microbes and enzymes than horse manure but has a lower visible fiber content. (The reason cow manure contains fewer fibers is that cows are able to digest cellulose, thanks to special bacteria that live in one of their four stomachs. These bacteria contain the enzymes needed to digest cellulose in the grasses they eat, so goodbye fiber!) Some people have reported success with llama and alpaca dung.

Manure should be as fresh as possible: composted or decomposed manure loses its enzymes and its adhesive quality and fibers break down. Manure should be sifted before use and can be used instead of chopped straw in finish plasters. You’ll need to experiment to determine how much to add.

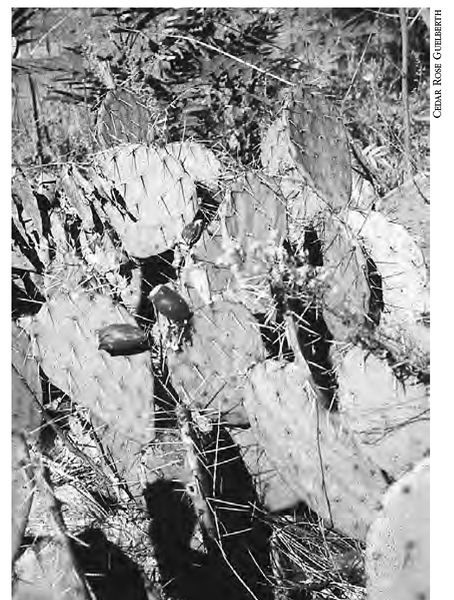

CACTUS PRICKLY PEAR. Prickly pear cactus “juice” is one of the most commonly used additives. Part of the reason for this is that it is one of the most prevalent species of cactus in the world: it can be found in deserts, grasslands, and some open forested areas. It grows in 48 of the 50 states in the United States, and in other parts of the world, such as Australia. In fact, in Australia prickly pear cactus became a nuisance, as it overran many parts of the country. Prickly pear cactus is also quite prolific in other parts of the world. In such instances, harvesting some won’t drive the species into extinction. Some species produce large leaves, too, which yield lots of material. One of the best prickly pear species, known as Opuntia ficus indica, grows tall throughout the deserts of the U.S. Southwest and Mexico. It produces few large spines, which make it easy to work with, and contains lots of pectin (defined below).

4-9: The juice from the pads and stems of prickly pear cacti increases the adhesion of a plaster, improves its workability, and serves as a stabilizer, making the plaster more water resistant and more durable.

The juice from the prickly pear cactus leaf pads and the stems of the cholla cactus serve many functions. According to some sources, they help a plaster set, increase its stickiness or adhesion, and they improve its workability. Cactus juice, as we call it, also serves as a stabilizer — that is, it helps make earthen plasters more water resistant and more durable. It also prevents dusting.

Cactus juice works well because it contains a water-soluble long-chain carbohydrate — a complex sugar or polysaccharide. According to veteran straw baler and mudder Bill Steen, this gooey substance, known as pectin, is a binding agent that increases the adhesion of an earthen plaster. Pectin is also responsible for increasing the water resistance of earthen plaster and has been used to augment lime plasters in both Mexico and the southwestern United States for hundreds of years.

In some locations, prickly pear cacti are just too small to work with. The amount of pectin varies considerably among the different species of prickly pear cactus, too. In such cases, you will need lots of material to create sufficient additive.You’re better off using cooked flour paste, which performs a similar function and is easy to prepare.

OILS. Various oils can be added to earthen plaster to enhance its water resistance and durability. Linseed oil is one of the best but is used only for finish plaster coats. When exposed to oxygen in air as the plaster dries, linseed oil becomes oxidized, and is then “fixed” in the wall. It also increases the flexibility of a finish plaster, allowing it to expand and contract more than untreated plaster, which helps to reduce cracking. Linseed oil does all this while continuing to allow wall to breathe — that is, it permits water vapor to pass through.

EXTRACTING CACTUS JUICE

Approximately two weeks before plastering is to begin, place chopped prickly pear leaves or cholla stems in a plastic bucket or other air-tight container. Fill the container with water. In about one to two weeks, mucilage will be formed. Separate it from the remains of the leaves and use immediately. If mucilage is required more quickly, chop prickly pear leaves and cholla stems, then immerse in water and boil for a while. Mucilage can then be separated out. You’ll need to experiment to determine the amount to use in your plaster mix. We recommend starting with one cup in five gallons of plaster.

Be careful, however: too much oil in your plaster can break down exterior finishes. How much should you use? The following are useful guidelines: use about 0.5 to 1.0 percent (by volume) linseed oil in the finish coat, or try a tablespoon of linseed oil mixed in a five-gallon bucket of plaster.

A variety of other oils can be added as well, including canola oil, hemp oil, and flax seed oil. However, these have less body than linseed oil — that is, they are less viscous (thick). The more viscous linseed oil also adds pliability, which other oils don’t.

Oils come in variety of commercial preparations. The commercially available products you buy at lumberyards and hardware stores, however, can contain some pretty toxic components, even when the label reads “100% oil.” From the perspective of personal and environmental health, the all-natural oil products are far better. Use food grade oils or products from Bioshield,AFM,Auro, Livos, and other suppliers listed in the Resource Guide.

Although oils have been used by many plasterers, we recommend caution. This seemingly good idea can cause disastrous results. In exterior applications, there is a fine line between too much and not enough oil. Small amounts added to a mix slightly increase the durability of a finish coat.Too much oil may appear to provide a well-sealed wall surface in the short term. Over time, however, the oil-treated finish coat will begin to heat and cool as a separate layer, causing the finish coat to separate from the underlying plaster layer, most often in exterior applications.

Another concern is that exposure to weather can cause small openings or pores to form in the surface, allowing moisture to enter the plastered surface of a wall. Moisture may become trapped in the plaster layers beneath the finish coat, eventually eating away at the base layers. As a result, the finish layer will peel off the wall. However, oils and waxes can be applied to interior finish coats for a beautiful finish.

WARNING!

Although oils can be added to produce a beautiful and durable exterior wall finish, we recommend caution. Some people have used oil in finishes to waterproof walls while disregarding the design elements essential to the success of a plaster. Too much oil, and exposure to the sun and weather can actually cause the finish plaster on an exterior wall to break down and peel off. Oil in base layers can prevent good adhesion of one coat of plaster to another. Too much oil in a finish coat can make it difficult to repair finish plaster, too. If you use an oil in your finish coat, remember that more oil does not mean more protection. Less is better!

Silt vs. Clay: Understanding and Detecting the Crucial Differences

Before we move on, we need to say a word or two about silt. Let’s take a few moments to answer three basic questions: What is silt? How can you tell it apart from clay? How does it affect plaster?

WHAT IS SILT? Silt, like sand, is made of tiny particles of rock, which are intermediate in size between sand and clay — that is, they’re larger than clay but smaller than sand. Unlike sand, silt particles are much too fine (small) to see with a naked eye.

Silt particles are irregular and diverse in shape, seldom smooth or flat. Some geologists think of silt as “microsand particles” with quartz being the predominant chemical component.

When wet, silt often feels slippery, as clay does. If you moisten some silt and rub it between your fingers, you’ll find that it feels a lot like clay.The reason for this, say geologists, is that silt particles often contain a thin film of clay on their surfaces.This gives silt some plasticity and cohesion (stickiness). It is also water-absorbent.All three are properties of clay.

This, however, is where the similarities abruptly end. Clay particles, as we’ve noted several times earlier, are flat plates. Clay is much more plastic, too, meaning it is highly workable. That’s why potters use it and why kids play with it. The worm test we described earlier relies on clay’s plasticity. If the clay content of your soil is high enough, you can bend the clay worm around your finger and it won’t break — so long as it is wet enough.The clay’s plasticity allows the dirt worm to bend easily: the more clay, the more bend.The less clay, the more the worm has a tendency to break at the bend.A soil with a high silt content has much less plasticity: a dirt worm will break apart very easily.

While both clay and silt feel sticky, clay is much stickier. Clay molecules are held to one another by water molecules.This bridging effect gives clay its plasticity as well as its stickiness.

Although silt feels slippery when held between the fingers (because silt particles are coated by a thin film of clay), silt doesn’t have much binding power — that is, it is not as adhesive as clay. Too much silt in a plaster may interfere with clay’s ability to bind to sand and straw and to other clay molecules.

Although excess silt can physically block clay from binding to sand and straw and therefore may produce a weaker plaster, don’t panic if you have silt in your subsoil (which is highly likely!). Some silt is beneficial: clay-dirt containing some silt can produce a highly effective and lovely plaster that is easy to apply and durable. Some of our best plasters have had a fairly high silt content! Note, too, that silty subsoils are easy to amend with natural additives.

CHARACTERISTICS OF SILT

• Extremely fine particles, invisible to the naked eye

• Slippery when wet

• Water repellent, if in a thick enough layer

• Not as sticky as clay

• Poor adhesive and binding agent

• Impairs water vapor movement when concentrated in a plaster

• Tends to crumble rather than clump when it dries

• Feels like a very fine powder but is gritty when rubbed on your teeth

• Easier to dig through than clay

TESTING FOR SILT. To assess a soil’s silt content, take a pinch of wet dirt between your thumb and index finger and squeeze them together. Then try to pull them apart. If your finger and thumb stick together, there’s probably sufficient clay in the soil. If they don’t, there’s probably less clay and more silt.You may need to add clay or flour paste (or some other additive) or seek another source.

Another test to determine the amount of silt vs. clay is to take a small clump of wet soil (about the size of a golf ball) in your hands. Flatten it against your palm, then turn your hand palm down. If the clump sticks to your palm, you’ve got more clay and less silt. If it doesn’t, your soil probably has more silt.

DISTINGUISHING CLAY FROM SILT IN THE FIELD. Being able to distinguish clay-rich soil from silt-rich soil will come in handy when gathering clays for plasters, finish coats, and alises (clay paints). Telling clay and silt apart in the field can be quite challenging — which is why it’s important to test an imported soil before it is delivered to your site!

You can distinguish between clay- and silt-rich soils by the “stickiness test” we’ve just mentioned. You can also tell by the way the two harden: when high-clay soil dries, it tends to clump. Clay clumps can be quite hard — almost rock hard! If you try to crumble it in your hands, you’re in for some work. Dirt containing silt, on the other hand, crumbles much more easily.

Clay can make digging difficult. If a soil contains a lot of clay, it is harder to dig in. The soil also tends to come out in clumps. Silty soils, even with high clay content, are easier to dig through and don’t clump nearly as much as clay-rich subsoils. Pure clay curls when it dries; silt doesn’t. (When silt is evenly distributed throughout a soil, it prevents clay from clumping and makes dirt easier to dig and sift, and sometimes makes an ideal starting material for plaster.)

There are two other physical characteristics that help to distinguish between clay and silt. In loose soil, silt feels like fine flour when dry. Rubbed on your front teeth, it feels gritty.When ground, clay is even more powdery.When you rub clay powder on your front teeth, you won’t feel any grittiness.

Now that you know how to distinguish clay from silt, we want to be sure to reiterate an important point: silt does tend to decrease the binding capacity of clay in a plaster, but some silt is okay, and can actually be of benefit. As noted earlier, some of our best earthen plasters have had a fairly high silt content. Clay-dirt with some silt can produce a beautiful material that is workable and easy to apply. So don’t panic if you encounter silt in your subsoil.

Are there any Types of Bagged Clays or Clay-Rich Soils You Should Avoid?

Clays come in many varieties, each with its own name. For example, you’ll encounter kaolin, a whitish clay, and bentonite, a highly expandable clay.As we noted in Chapter 2, the differences in clay are due to differences in their chemical and physical properties. In other words, each one has a unique chemistry as well as a unique microscopic structure. Each clay behaves differently, too: although all clays are sticky, plastic (workable), and expansive, they differ in these properties. Some are stickier and more expansive than others. Even within the same family of clay — for example, the kaolins — you’ll quickly discover variations in clays from one region to another. Georgia kaolin differs from Iowa kaolin, which differs from kaolin from China. Should you avoid any particular types of clay?

Yes. Bentonite and clays with similar properties. Bentonite is one of the worst clays for earthen plasters or clay-based finishes because it is highly expandable. It shouldn’t be used because it just expands too much (19 times) and will cause excessive cracking no matter how much sand you add! Bentonite is also so intensely hydrophilic (water-loving) that it quickly absorbs water. Put a drop of water on it, and the bentonite binds the clay so rapidly that the plaster is virtually unworkable. We don’t recommend the use of bentonite or other similar clays in earthen plasters or clay-based finishes.

AVAILABLE VS. UNAVAILABLE CLAY. Clay is a remarkable substance. However, some deposits (both underground and surface ones) contain so much hydrophilic clay that they’ re extremely difficult to work with.The clay can be so bound up that it is difficult to extract. Once you excavate the stuff, the chunks are rock hard, and nearly unbreakable unless you’ve got a sledge hammer! In this state, the clay is obviously not suitable for mixing.

If you encounter clay such as this, you will need to harvest it, then soak it in water for a while — as long as it takes to soften it.You’ll then have to stomp on it or smash it, then mix it with your hands or some other implement.This will start to break up the clumps; additional soaking will probably be required, and you may have to repeat the process several times until the clay is hydrated and workable. You may want to locate another source of good-quality clay-rich dirt (containing more silt and sand)from a local source, for instance, a gravel pit, in the subsoil, or along on the banks of nearby river or pond where the soaking has already been done for you.

HEALTH WARNING: WEAR A MASK!

Soil, clay, sand, and fiber are all natural materials and relatively safe to use. However, you should be aware of some potential health hazards. Most clays, for example, consist of extremely fine particles of aluminum silicate; kaolin is a good example. Used as an extender in medicines and as an absorbent in diarrhea medications, some consider it to be safe to ingest, although breathing aluminum oxide is clearly not recommended.

Powdered clays are especially troublesome. Clay particles are so fine that whenever a powdered clay is scooped out of a bag, poured from one container to another, or sifted, it produces a dust cloud. Dust is produced by many other activities involved in plastering a home: screening or sifting subsoil, pouring bagged clay, shoveling sand, or chopping up straw for plaster, and adding pigment to mixes. Be sure to take precautions. Dust can be breathed into your lungs and may cause serious illness. To protect yourself against any possible health problems our advice is: always wear a certified dust mask when working with any of these materials in a dry form.

Quick Recap

Well, that’s it.You understand that earthen plasters are made of clay-soil, sand, fiber, water, and various additives, and know what each component contributes to the plaster. Clay is the binding agent that holds this complex mix together both when wet and when dry. Sand provides structure and strength. Fiber provides strength and some flexibility. Like sand, fiber prevents cracking. Water allows all of the components to be mixed and applied easily to the wall. Additives provide additional adhesion, which is to say, they assist clay as a binding agent. They can also increase the durability of a plaster and its water resistance.

To make a durable, long-lasting plaster requires the proper ratio of each. As noted earlier, the proportions of these ingredients in your plasters will vary depending on the ingredients themselves. Clays found in subsoils are chemically variable and behave differently. The amount of sand and silt also varies from one site to another.

Because subsoils vary, rely on the feel of a plaster, the way it goes on the wall, and the way it dries to determine suitable recipes (a process we describe in detail in Chapter 6). Test your mixes well. Start with a couple of small projects — for example, a shed or outbuilding — before you plaster a whole house. The experience will pay huge dividends.

Now that you understand the components of plaster, we’ll turn our attention to site preparation and mixing earthen plasters.