Chapter Six

When I Started to Understand What Kalyna Aljosanovna Was

Kalyna Aljosanovna insisted on walking back to Desgol proper with us.

“Let’s talk through your predicament, Radiant,” she said, clicking her tongue thoughtfully. “That, at least, I can do for you, and may even enjoy!”

I felt heartened by this, even though she was offering so very little. Perhaps I would grab onto any hope, just then; perhaps I was just relieved to have someone new to talk to about it all.

“Well,” I began, walking beside her, as Dagmar hung behind, “do you know anything about why my papers are suddenly invalid? About what happened in Loasht?”

I did not bother to say, After all, you’re so very worldly, but I thought it, and I’m sure she heard it in my voice.

“I’m sorry to tell you,” said Kalyna, “but nowadays I try to know as little about politics as possible. I’ve had enough of that to last a lifetime.”

Dagmar let out a gruff laugh that seemed knowing, conspiratorial, and accusatory all at once.

“You’ve done enough and you’ve had enough,” she grumbled. “But when I have had enough . . .” She trailed off, waiting to be argued with. Kalyna did not take her up on it.

“But what little have you heard?” I pressed. “Any clarification would be welcome! I still know so little of what happened, of . . . well, what I am now. Am I still Loashti? Am I a stateless alien?”

“All I know,” replied Kalyna, “is that the Loashti delegation came once more to the Council of Barbarians.” She shrugged. “I think I heard that a Loashti dignitary gave a speech about curbing unsavory elements in Loasht and abroad—elements that were the ‘real’ reason for the Tetrarchia’s age-old fears of our neighbor.”

I felt a numb terror inside of me. As if what I’d just heard was both too big and terrible to be possible, and too obvious and inevitable for me not to have already known it. How deep into Loasht had Aloe’s poisonous ideas seeped? What dizzying new heights had my old colleague reached?

“That’s much more than I’d heard,” I managed to say. “Thank you.”

“I thought you weren’t paying attention to politics,” said Dagmar.

Kalyna grinned. “Well, Dagmar, I was not personally responsible for this Council of Barbarians taking place. I think that’s quite uninvolved, for me.”

Dagmar sucked her teeth loudly. I furrowed my brow and walked a little faster to get a better look at Kalyna’s face.

“What do you mean ‘personally responsible’?” I asked.

“She wasn’t,” grunted Dagmar.

“Another time,” said Kalyna. She acted as though Dagmar’s comment hadn’t happened and waved away my curiosity like one would a silly question from a child.

“Beyond what I’ve just told you,” Kalyna continued, to me, “I’m sure I only know what you do: that, in Quruscan at least, Loashti with papers of certain colors are in trouble. From my last time in Loasht, I happen to know the Zobiski’s are pink.”

“I still don’t know what could have changed so quickly,” I murmured. Even with Aloe and his followers terrorizing people, Loasht did not alter itself overnight. And overnight to Loasht was decades, if not centuries—while other countries rose and fell.

“But Loasht has a new government, doesn’t it?” asked Kalyna.

I stopped walking and stared at the small, round houses of Desgol. There was a very long pause as I tried to make sense of what I had just heard.

Finally, I managed: “What do you mean, a new government?”

“You hadn’t heard? The Grand Suzerain died, oh, four or five months ago. There’s been a new one since.”

There were, essentially, three reasons why learning this shocked me.

- This was the first I’d heard of it. I suppose the movements of internal Loashti politics didn’t matter much to the average people of the Tetrarchia, so long as it didn’t change their lives.

- A new Grand Suzerain didn’t normally change the lives of Tetrarchic citizens, nor even of Loashti. All leaders throughout Loasht bowed to the Grand Suzerain—they did not get to bicker and skirmish and make deals like Tetrarchic monarchs—but the goals of the Grand Suzerain and his government shifted only gradually.

- The Grand Suzerain at the time I left had been younger than I.

Had I still been in Loasht, I would have learned at least the official version of whatever happened to the old Grand Suzerain, far from the truth as that might be. Out here in the Great Homunculus of the Tetrarchia (they even called it an “experiment”!), I knew no more than what Kalyna told me.

Of course, if I’d been in Loasht when the old Grand Suzerain died, I would also have been there as things turned worse for the Zobiski. I thought, for a moment, about Silver, and my community in Yekunde, and then stopped myself. It was all too terrible to contemplate.

We got back to the tavern in Desgol quite late, when its common room was emptier. I did not see Sofron anywhere, which was disappointing. Kalyna smiled at the large man behind the bar, who greeted her by name.

The group of Rots Dagmar had found earlier were still there, six of them taking up two tables. They had the look of men who would continue drinking even later into the night, possibly to escape something. One smiled and waved at Dagmar, who waved back and said something in Rotfelsenisch. The others glared quietly over their drinks, and I tried to remember if that was how they had looked earlier in the night. Was this simply their way, or was there suspicion in their eyes? A threat?

As we started up the stairs to the second floor, Dagmar leaned over to Kalyna and said quietly, “Ex-Purples, by the way.”

Kalyna nodded thoughtfully.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“Rotfelsen politics,” replied Kalyna, as though this explained everything. “They have strange ideas there.”

“I’m right here,” said Dagmar.

“Am I wrong?”

“Well, no.”

Kalyna turned partly toward Dagmar, walking sideways up the stairs. I trailed behind them both and fought the urge to glance back at the Rotfelsenisch men in the tavern.

“Papa will be delighted to see you, Dagmar.”

The sellsword beamed with what seemed to be, since finding Kalyna, her first smile that had not been coerced.

“It’s been some time,” said Dagmar. “How is he without his mother?”

“The Villain of His Life, you mean,” corrected Kalyna, as we came to the top of the stairs.

Dagmar snorted. “Of your life, but not—”

“You didn’t know her that long.”

I saw Dagmar’s shoulders tighten, but she didn’t respond.

The stairs, the railing, and the landing were all of the same dark, lacquered wood. It was nothing like Yekunde or Abathçodu, and yet something about it felt . . . homey. We walked toward a similarly dark door, until Kalyna put out a hand to stop me. Gently.

“I’m sorry, Radiant, but right now it will worsen my father’s health to meet new people.” She clicked her tongue. “No matter how much he thinks he’d like to.”

“I won’t say a word,” I replied. All I wanted was to put down my heavy packs. To sit for a moment. To sleep if I could.

Kalyna shook her head. “Even being in the room will pain him.”

“How?” I asked.

If Kalyna found this irritating, she hid it marvelously. “Trust me,” she said.

“Perhaps Aljosa can see something helpful about Smart Boy,” Dagmar offered.

“Not worth it,” replied Kalyna. “Radiant, my room is next door.” She pointed. “Wait in there, if you please.”

I nodded. I realized I was scared of being left alone, but Kalyna and Dagmar seemed so supremely confident and comfortable (even if Dagmar’s confidence had been truly shaken by Kalyna, somehow), that I was too embarrassed to voice my fear. I walked into the next room.

“And please sit at the far end,” Kalyna added from the door, in Zobiski. “I know it’s an odd request.” She pointed to a small, red velvet couch pressed against the wall farthest from her father’s room.

I couldn’t help feeling this was some sort of caution around supposed Loashti magics—as though my very presence would poison her ailing father. Did she know more about the official reasons for why Zobiski, and others, were alienated from Loasht?

Something of this must have shown on my face, because she added, “My father’s mind is troubled. He loves to be around people, yet even proximity to others can hurt him—particularly to others who may be heading into, ah, difficult situations.”

I must have looked quite confused. But I didn’t want to argue, given the circumstances.

It occurred to me that I might be in some sort of trap, but I couldn’t quite figure out the why of it. Kalyna seemed interested in my plight only in a vague, theoretical sense, and if Dagmar had wanted to abandon me to my fate, or sell me out, she would have by now.

Also, I was very tired. So I mercifully dropped my packs and sat on the couch. If I had to run from these two, where would I even go?

“Thank you for understanding,” said Kalyna, closing the door behind her.

I sat on that couch for what felt like hours, but was probably no more than fifteen minutes, perhaps taking Kalyna’s request too much to heart. Once seated, I did not move, lounge, rustle, or even breathe too deeply. Whatever her reasons for restricting my movement, she had made me believe they were clear to her, that she was doing me a service by her kind request, and that she would somehow know if I disobeyed.

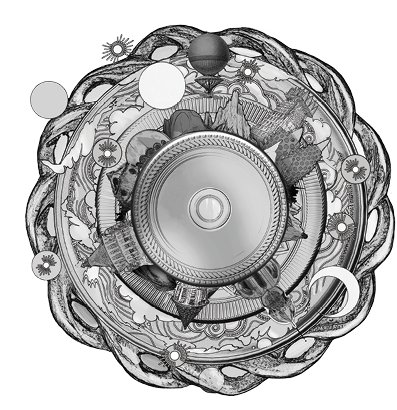

Thankfully, for a time, I was distracted by Kalyna’s room itself. The walls were of the same dark, lacquered wood as everything else, but brightening it up were silk drapes of orange, turquoise, and gray, and a marvelous number of colored glass beads everywhere. There were sitting pillows covering most of the floor, like a sea of multicolored textile prints depicting flowers, farmers, abominations, and most anything else you could imagine. The bed against the far wall from me was unremarkable and clearly property of the tavern.

In front of the couch where I sat was the only other piece of furniture: a low, but long, golden (or at least gold-plated) table. Atop this table were a copper bowl of water next to a matching smaller copper bowl of sand; a Loashti-style incense burner shaped like a rhinoceros’ head, meant to leak smoke through the eyes; a wooden carving of a chicken covered in a thousand little holes, each holding a real chicken feather; three decks of cards of entirely different sizes; and finally, an old, wooden tobacco pipe sitting in a circle of dried flowers.

Who was the person who stayed here? She had a number of ritual objects, certainly, but none that were cohesive within any traditions I was aware of. The room’s colorful—possibly garish—nature brought to mind the design of a carnival tent. Why had Dagmar thought Kalyna could help me?

Unfortunately, once I was done poring over all of that, I was forced to think clearly for the first time since leaving Abathçodu. I had passed many hours sitting alone in the mountains’ wilderness while Dagmar got us food, but there had always been noise, bugs, danger. Now I was alone, it was quiet, and the utter incongruity of Kalyna’s quarters had slapped me about the face, pulling me into clarity.

I did not know exactly where we were on a map, but if we had come down out of the mountains and were still in Quruscan, then we were farther from Loasht than where we’d started. I was alone—entirely alone—in what may as well have been the blasted center of the Tetrarchia. Alone in the room of some . . . carnival mystagogue who was supposed to save me, but seemed uninterested. I began to run through the unspeakable names of Loasht’s Eighty-Three gods in my head, desperately fumbling for what I might have done to displease every single one of them.

Then the door was wrenched open, and I felt my heart seize up—but it was only Dagmar. She stomped into the room, nearly making me jump, looked me in the eyes, and growled something in Rotfelsenisch. Dagmar always seemed so composed in every situation, but now she radiated rage.

I stared, mortified, until she realized I had not understood her.

Dagmar smiled weakly, tromped over, and much to my surprise, slumped onto the couch next to me. I assumed we’d had enough time together in close quarters to last a lifetime. In the most Dagmar-like fashion, she stretched one long leg over the armrest, and I heard the wood creak.

“That woman,” she said. “That’s all I was saying just now. No one else has ever . . . what’s the Skydaš version? Crawled in behind my eyeballs?” She looked at me.

I shrugged. “I don’t know the idioms.”

“Well, she really gets in behind my gods-damned eyeballs. Roots around in my brain. Picks and prods. If someone else made me feel that way, feel a tenth of that . . . type of way, I’d kill them.”

“But,” I couldn’t help myself, even though I knew this was imprudent, “it doesn’t take much for you to kill someone, does it?”

“That depends,” she replied. “And the people you can’t kill can really get on your nerves.”

I wondered if I was always so easily bothered by others because I couldn’t imagine killing anybody. What a dark thought. I decided to move back to the original point.

“What did she do?” I asked. “Just now, I mean.”

“A thousand little things! Told me I was part of her family but treated me like a pet. Said I abandoned her when she needed me, while refusing to understand why I was driven away. Assumed I’d spent the past eight months in Quruscan just to be closer to her, waiting to run back to her. And that makes my blood rise, because it may well be true. I gave up my commission for that woman!”

She slammed a large fist against the couch cushion, and its frame groaned from the force. I felt it shake. I knew Dagmar wouldn’t hurt me, but this sort of angry outburst was too familiar to me, and I froze up. Even though she wasn’t looking at me, somehow she knew I’d reacted, because she hung her head sheepishly.

“Sorry,” she muttered. “And now, she digs at me with polite, veiled little asides during what should have been a pleasant reunion. In front of Aljosa, no less!” Her voice was rising again. “As though I would not want to spend some time with him for myself and not only . . . not only through her. I love him too, in my way.”

I ventured: “And do you also love her?”

There was a long silence.

“I suppose,” she said at last. “I didn’t at first—we were just having fun. But people change. My feelings changed. She changed too.” Dagmar sighed and sank into the couch, leaning her head back and staring at the ceiling. Her dark blonde hair was mostly tied in a little knot at the back of her head. “Or maybe she was always like that, and I just got close enough to notice.”

“Do you think she loved you before, and doesn’t now?”

“I wish I knew,” she sighed. “I thought she would want to help you. Thought she and I would get you to your family in Loasht, and it would be like old times. Maybe then I’d be able to figure out what she felt. Or . . .”

Dagmar coughed, then looked down at the table, at the pipe surrounded by dried flowers.

“Or at least,” she muttered, “I could pretend it was old times again for a little while.”

She grunted and shifted out of her lazy positioning, sitting forward, elbows on her thighs, as though about to leave.

“Maybe,” she said, “I should go back to Rotfelsen. See if Lenz or the mad prince will take me back.”

Suddenly, any care I had for Dagmar’s personal problems drained away.

“But what about me?” I blurted.

She blinked and turned to look at me, surprised by my outburst.

“Well,” she said, “you might be safe to stay in Desgol. I don’t even need you to pay me much, just whatever you have—”

“I’m very sorry about your romantic frustrations,” I said, probably sounding more facetious than intended, “but I won’t survive being alone in a hostile country!” I threw out a hand, gesturing fervently at nothing in particular. “Stranded in this wilderness, imagining terrors visited upon my family, while I am hunted by superstitious barbarians, abandoned here by a lovesick . . .” I trailed off, stuttering, looking for the word.

“Lovesick what?” asked Dagmar. Her voice was even, her face was still, and her eyes were narrowed.

“I don’t know,” I sighed.

“Yes, you do,” she said. “Lovesick what?”

“Do you two mind?” asked Kalyna.

I jumped in place. Dagmar turned her head slowly to the door, but I think even she was surprised. Kalyna was standing in the doorway, looking only slightly annoyed.

“Papa needs to sleep, so please keep quiet.”

“How much did you hear?” asked Dagmar.

“I came in at ‘superstitious barbarians.’”

“I’m sorry.” I swallowed hard. “I didn’t mean . . .”

“Yes, you did,” said Dagmar. She turned to look at me, and she was smiling now. She even winked.

Kalyna walked in and shut the door, leaning against it.

“I’m certainly not insulted,” she said. “Just close the door next time.”

I opened my mouth to apologize.

“And I understand your worries, Radiant,” she added, cutting me off. “Better than you realize.”

She looked up at the ceiling, muttered something in Masovskani, and then let out a long sigh. Her eyes snapped back to me, and she smiled wearily.

“Which is why I will help you get to Loasht and find out what has happened to your family.”

Something that had been coiled inside me seemed to unspool. I felt a glimmer of hope. I still didn’t entirely understand why Dagmar thought this cutthroat could help me, but she must have meant it. Dagmar did and said very little that she did not mean. Besides, if Kalyna helped me, then surely so would the lovesick sellsword who had stayed in Quruscan for months waiting for her.

“Wonderful!” said Dagmar. She stood up, looked down at me, and clapped a large, callused hand on my shoulders. “Now you won’t need me, Smart Boy!”

My hope was instantly doused.

“Wait!” I cried.

Dagmar smiled. “Of course. You’re right, Smart Boy. There’s the money. Well, I have taken you half of the way; half of what you had when I found you sounds reasonable.”

My hands shook as I drew out my purse—a beautiful little striped, velvet thing I’d bought in Abathçodu—causing my remaining coins to jangle loudly. I had not counted what sort of dent food and supplies had put in the fifty silver abazi I’d had when our flight began.

“But then,” added Dagmar, “I like you. Let’s say twenty abazi, yes?”

I nodded and began tremblingly counting out coins.

“Please, please don’t leave me,” I begged.

“Why? You have Kalyna now.”

I wanted to scream that I didn’t know this other woman. Hadn’t Dagmar wanted to spend time with Kalyna? Hadn’t she, perhaps, only helped me because she saw a way to pretend it was like “old times”? None of these things, however, seemed appropriate to say in Kalyna’s presence. Instead, I put twenty silver coins into Dagmar’s callused hand.

“Thank you,” she said, pocketing the coins and giving my shoulder another hard pat, followed by a tight squeeze. “You’ll be just fine. Really. Kalyna may get in behind my eyeballs, but that’s only because she can get behind everyone’s! You’ll see. If anyone can get you across that border, it’s her.”

Dagmar turned to leave, and Kalyna looked at me quizzically, mouthing, Get behind what?

I shrugged at her and shook my head.

Dagmar made for the door, against which Kalyna was still leaning. The smaller woman inhaled, as if about to speak.

If this Kalyna was so good at manipulation, I allowed myself to hope that she would find a way to convince Dagmar to stay.

“I’m sorry about earlier, in front of Papa,” said Kalyna. “I didn’t know what I was saying.”

“You always know what you are saying.”

“I always act like I know what I am saying. But it had been a while, and I—”

“From the moment you got used to me, you began to pick at me! As soon as I stopped being just . . . just a novelty to you!”

“Now, Dagmar, that’s not fair—”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Dagmar. “Can I leave? Or must I break the door, and you, to do so?”

Kalyna sighed and stepped away from the door.

“Look,” she said. “Go your own way in the morning, but at least let me give you a place to stay without paying. You can sleep in my room—”

Dagmar began to protest. Loudly.

“Both of you!” Kalyna interrupted. “And I will sleep in Papa’s. You won’t have to deal with me.”

“Smart Boy?” Dagmar turned to look back at me.

I felt overwhelmed. My future was murky and unknowable. A wily cutthroat said she’d take me home, where my family was perhaps already dead. Even the smallest possible choice presented to me felt impossible to make. So, instead of making a choice, I just said how I felt.

“I!” I yelled. “Have never been more tired in my life! And I don’t know what I can even afford right now!” Then I pulled my feet up onto Kalyna’s couch, lay sideways, and turned my back to them.

I heard Dagmar chuckle and say, “Fine.”

If anything was said next, I didn’t hear it, because I was asleep.

I dreamed of angry mobs, just as I had every time I slept well enough to dream since Abathçodu. But this time the yelling was closer, more insistent, more realistically muffled, and in a language I didn’t understand. The sound that actually woke me was of Dagmar launching herself out of Kalyna’s bed, buckling on her sword, and moving across the room all at once, knocking over Kalyna’s small copper bowl of sand.

“What?” I muttered.

“I don’t know,” she snapped. “Grab your bags and go quietly out the back. My bags too.”

Dagmar vanished into the hallway, leaving the door open. That was when I realized there were people yelling downstairs in the tavern, and not only in my dream.

I began to gather up my bags, and Dagmar’s as well, with numb fingers, desperate to move faster than my tired body could manage. We had not really unpacked, but there were a few coats and hats to gather up.

Blasting up the stairs and through the open door were the sounds of tables and chairs being knocked and skidded about, while men yelled in guttural Rotfelsenisch. The only word they said that I knew was “Loashti.”

I tried to gather our things much faster, but my hands would not stop trembling. The Zobiski memory pounded through my every vein.

I heard the sounds of bodies colliding and a voice that seemed to be Kalyna’s crying out in pain. Then the crunch of something—I hoped wood—and more Rotfelsenisch shouts as, I think, Dagmar arrived among them. The fighting began to sound more frantic. Some large, heavy piece of furniture shrieked and fell.

Kalyna yelled something in Rotfelsenisch. The only words I understood were “Dagmar” and the word for “don’t.”

I threw my packs onto my shoulder and strained to lift Dagmar’s as well. They were all so heavy, I could barely have carried them even if I hadn’t been tired and sore. I waddled out onto the landing with as much urgency as was possible, desperately looking for the back door.

Even as the fight raged on below, I found myself possessed by an ugly, stupid urge to sneak a look at Kalyna’s father, Aljosa, while she was occupied. I think I would have, if his door had not been closed.

Downstairs, a new group of thudding footsteps and yells joined the tumult, but these were in Cöllüknit.

Cautiously and laboriously, I crept to the edge of the landing, peeking carefully over the railing for a look at what was going on below.

At least I did not see the angry mobs of Abathçodu, nor the shouting Loashti followers of Aloe Pricks a Mare upon the Mountain Bluff. What I saw was a brawl: broken furniture, an overturned cabinet; a group of angry, drunken Rots who seemed mostly intent on Kalyna; Dagmar swatting one of those men aside and catching another in a headlock; the Quru tavern keepers yelling at the damned Rots to stop already.

“Outside! Outside! Outside!” boomed one tall Quru man with a luxurious mustache as he swung a broom handle over his head.

Two of the Rotfelsenisch men were on the floor, unmoving. One’s head was in a puddle of blood, soaking into his crushed hat and blond hair.

A Rot who was still up began to draw his sword, but he had exposed no more than a few inches of the blade before Kalyna yelled something in their tongue and stomped on his foot. Before he could react, Dagmar gripped Kalyna’s hip with a strong hand and slid her backward, stepping forward to take her place—in the same motion, Dagmar grabbed the man’s hand and slammed it down, resheathing his sword. When the hilt clacked into place, there was a small splash of blood, and he howled as he curled into a ball on the floor. I did not see if he lost a finger.

Dagmar’s left hand was still on Kalyna’s hip when she reached for her own sword. Kalyna moved closer, against Dagmar’s back, and put a hand on the taller woman’s shoulder. Kalyna said something, and Dagmar left her hand on the hilt, but did not draw.

The remaining three Rots in fighting condition were now mostly backing away from the Quru man swinging the broom handle. He continued to yell, “Outside!” as though it was a knight’s war cry from The Miraculous Adventure of Aigerim. Or, indeed, a spell of some kind, chanted until it became reality.

“Smart Boy!” roared Dagmar.

My gaze snapped to her. Dagmar was standing in the center of the tavern, breathing hard, ready to draw her sword, with her left arm still twisted back to protect Kalyna behind her. She did not seem to have broken a sweat, unlike Kalyna, who was pressed against her back, panting.

“Kitchen!” Dagmar ordered.

I nodded numbly, and then Kalyna and Dagmar were gone.

I began moving toward the stairs as quickly as I could, while carrying all of Dagmar’s and my things. It was pathetic to see, I’m sure, but no one was watching me. The three remaining Rots had indeed gone outside, and the Quru man with the broom was standing imperiously in the doorway. Of the Rotfelsenisch men on the floor, two weren’t moving, and I did not want to get close enough to see whether they were breathing. The third clutched his bleeding hand and did not seem to notice me. The tavern workers didn’t care about me in the slightest.

I hobbled back through the kitchen (it smelled wonderful, but I never did get to eat there) and emerged behind the tavern, where Kalyna and Dagmar were standing in the shadow of the next building. I was breathing much harder than either of them.

“Can you believe her, Smart Boy? Her pack was just sitting by the kitchen exit. Like she knew.” Dagmar was smiling as she said it.

“Like I can seeeeeeee the future!” retorted Kalyna, wiggling her fingers. “Or like I was ready, in case those men got belligerent.” She was also smiling, despite the blood around her mouth. “This has everything I’ll need for this little jaunt.”

“But,” I began, panting, “how did you know that those men would be the ones to come after me? I fancy I see angry mobs everywhere.”

“They weren’t after you, Radiant,” said Kalyna. “They were after me.”

“But they said ‘Loashti,’” I whispered.

“Rots always seem to think I look Loashti.”

Dagmar chuckled and took her bags from me, which was a relief. An even greater relief was that, for now, she seemed to be leaving town with us. I worried that if I asked whether Dagmar had changed her mind about accompanying us, she would then un-change it.

Just past the border of Desgol, with the tall grasses of the steppe in front of us, we slowed our pace slightly. Dagmar was still with us.

It was then that I realized exactly how tired, scared, and sore I was. My body did not want to move, and I felt like I could not catch my breath. Each step was an ordeal. And yet, I had learned something so confounding that its great glare blocked out even my exhaustion. I ignored the pain and sped up, so as to walk next to Kalyna and look at her face. Squinting and studying it in the dawn light that was just beginning to cut through the clouds.

“You look Loashti?” I asked, stupefied. “I don’t see it.”

“I do,” said Dagmar. “But I always thought it was cute.” She winked at Kalyna.

We walked for some hours through the high grasses of the Quruscan steppe. I kept waiting for Dagmar to leave, but she did not. As the spring sun moved high into the sky, we came to a little copse of trees at which I positively insisted we rest.

“I have hardly slept in days. If I go on like this, I will do something stupid and die, and you will not get paid.”

I felt like some sort of spoiled prince throwing this threat at them, but Kalyna and Dagmar actually seemed to think it a good idea.

The copse was no wider than a five-minute walk from end to end, and its trees were pleasantly tilted and gnarled by the wind, causing them to be shorter than the surrounding grasses, so it was quite well hidden. As it was a spring day, we had no need to light a fire: it was cold in the shade, but heavenly in the sunlight.

I settled down in a sort of divot in the roots of one tree, my back against its surprisingly smooth bark, half sitting and half lying down. I gazed absentmindedly at a nearby shallow pool of water no wider than a yard, and at the multicolored bugs that flitted about its edges.

Once I caught my breath, I was not able to sleep just yet, no matter how tired I was. Too many things were running through my mind.

“Why did those Rots in Desgol want to kill you?” I finally asked Kalyna, in Skydašiavos.

Dagmar, who had stretched out on a bedroll laid over grass and dirt, exhaled loudly. “I think I’ll go to sleep now.” She then put her hands behind her head and immediately did so.

“Some mess in Rotfelsen a few years ago,” replied Kalyna. She was sitting against another tree, a few feet from me, with her legs crossed. She darted her eyes to Dagmar, then back to me, and smiled. “Let’s switch to Loashti,” she said in Loashti Bureaucratic. “It will let Dagmar sleep—be less distracting.”

Sitting just a few feet away, stationary, and lit by natural sunlight, Kalyna was quite striking—and not just because a bruise was beginning to form around her left eye. There was a small scar on her upper lip, and her deep-set dark eyes seemed to be learning the workings of everything she saw. Her hair was mostly black, but with the copper tint of a Central Loashti (not I), which I suppose could explain the Rots seeing her as such. But her facial structure was unlike anything in Loasht; aquiline might be the word.

I felt myself liking Kalyna.

“What kind of mess?” I asked.

She laughed. “Politics, assassinations, unrest. Those men think me responsible for the death of their beloved leader, even though I did not touch him.”

“But were you responsible?”

She nodded. “Yes. And proud of it. He was an ass and a tyrant, and a well-protected one to boot.” Kalyna allowed herself a smug grin.

“But aren’t you . . . ugh, Eighty-Three, I shouldn’t ask this. The last thing I want in the world is for us to go back to Desgol.”

“Go on.”

“Aren’t you worried about your father? If they hate you so much, might they hurt him? Or might someone else mistake him for Loashti?”

She shook her head. “The Rots don’t know about him, and only Rots ever think we look Loashti. But Little Bolat and Smiling Zhuldyzem and the others working at the tavern know my father well. They even like him! I’ve paid them quite a lot to look after him: keep him fed and well groomed, listen to his ramblings, and a thousand other things that he needs. A thousand things, each one solely my responsibility for years upon years.” She let out a long, contented sigh. “I love him, but I’m happy I can finally pay others to do some of it.”

I had a feeling she was trying to make me curious about other parts of her life, to get me away from my original question. I am not so easily swayed.

“But how can you be sure he’s safe? Those Rotfelsenisch men learned of your presence somehow. They must have been suspicious when they saw us come back to the tavern. They could easily have seen the room you went into.”

“No, no. They didn’t.”

“You don’t know that! Maybe they have been hunting you down! What if they spent days asking around about—”

“Radiant,” she interrupted, looking me in the eye. “They knew who I was, because I told them.”

“You . . . told them?”

“Specifically,” she continued, “I packed what I would need for this trip, left it by the back exit, came into the common room, got their attention, and then told them exactly how their beloved leader died.” She smiled languidly up at the blue spring sky. “Actually, I embellished a little.”

I opened my mouth to speak, but I could not form a response. I simply sat there.

Kalyna’s smile dropped a bit, but she continued to look entirely calm, gazing off into the distance. Then she addressed what my next step was to be before I even conceived it.

“If you tell Dagmar,” she said, “then she won’t come with us. Meaning you and I will be as good as dead.” Kalyna cleared her throat. “Which is”—a yawn—“exactly why I started that fight in the first place. She was going to leave us to our fates, again, but I can’t very well get you safely to Loasht if we’re killed along the way.”

“Why . . . ?” I stammered.

“I know, I know, I wasn’t going to help you. But I do feel for you, and I realized that Dagmar was going to leave you to your own devices.”

Had she realized, I wondered, or had she been listening to our conversation at the tavern before she interrupted it?

“I thought,” Kalyna continued, “that I could tempt her into helping you with my presence, but she still decided to leave. So . . .” She shrugged slowly and then gestured to her bruise.

“Wasn’t it . . . painful?” I asked.

“Very.”

“How could you invite that sort of violence on yourself? Weren’t you worried they’d break something, or kill you?”

She turned her head to the side, showing me her angular profile. “Does this nose look like it’s been broken?”

“I don’t know. Maybe. It is bent.”

“That is its natural shape,” she laughed, “which has been retained over decades of beatings.” She turned back to face my general direction but still looked up at the sky. “In my family, I had to learn quickly which blows I could take and which I could not. Naturally, sometimes things can get out of hand, but everything carries risk.”

“Your father beat you that much?”

“Gods, no! Papa would never hurt me. And Grandmother was too smart to break anything. The family business simply attracted that kind of attention.”

I was about to ask about this “family business,” but again thought Kalyna was using my curiosity to steer the conversation away from where it had begun.

“And Dagmar?” I managed, shaking my head. “That was a terrible thing to do to someone who cares about you.”

“Yes.” Kalyna did not seem glib: her smile melted away, and she sounded as though she meant what she said. “But so is abandoning them to die. Or abandoning them right when their grandmother is dying—no matter how terrible the old woman is.” She sighed and finally looked directly into my eyes. “Besides, in the past, it was always Dagmar who would instigate a little violence to bring us back together.”

“Fine. Why tell me all this?”

“Because you ask a lot of questions. You were already on your way to figuring out something was off.” Her smile returned. “Also because, now that I am dedicated to helping you, I want you to understand how far into deception I will go for you, Radiant.”

“And what will this deception cost me?”

Kalyna raised her hands, palms upward, in front of her, as though presenting me with something. Then she smiled brightly.

“Nothing, Radiant.”

“Why?” I’m sure I looked skeptical. “Do you also want to trick Dagmar into thinking it’s ‘the old days’?”

“Not at all. But I . . .” She breathed in deeply, as though she was about to make a great confession. “I want Dagmar to feel useful. And believe it or not, I truly do want to help you—some things about your plight are very familiar to me. And, well, I truly am not desperate for money anymore.” She laughed. “It sounds so outlandish to say.”

“I’m not sure I believe you.”

“That’s fair.” Kalyna closed her eyes. “Sleep well.”

I sighed very loudly and pressed my head back against the tree trunk, looking up at its fluttering, deep green leaves. Then, I admit, I did sleep well.