Chapter 2

Beginnings

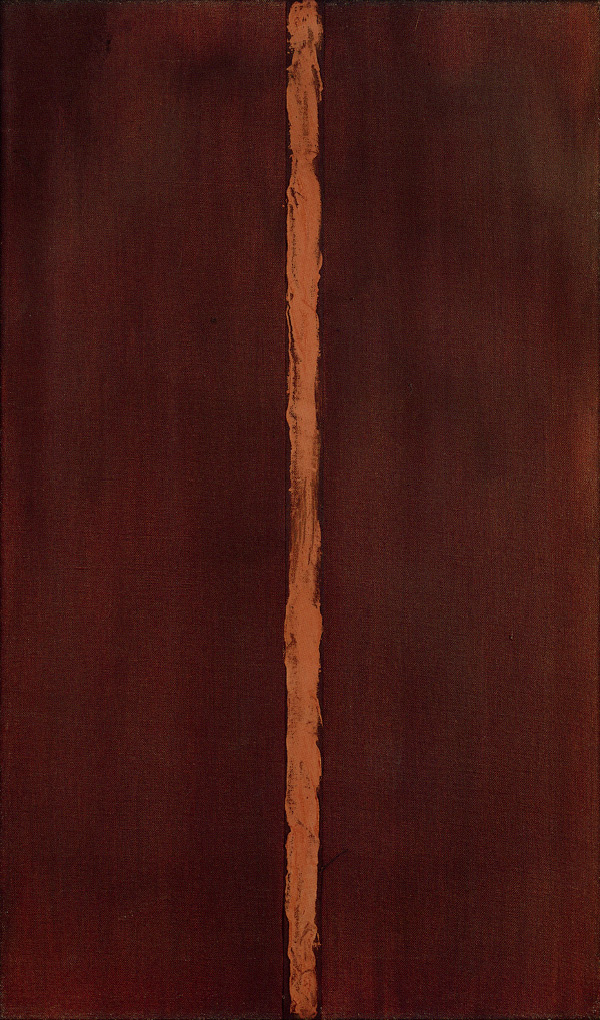

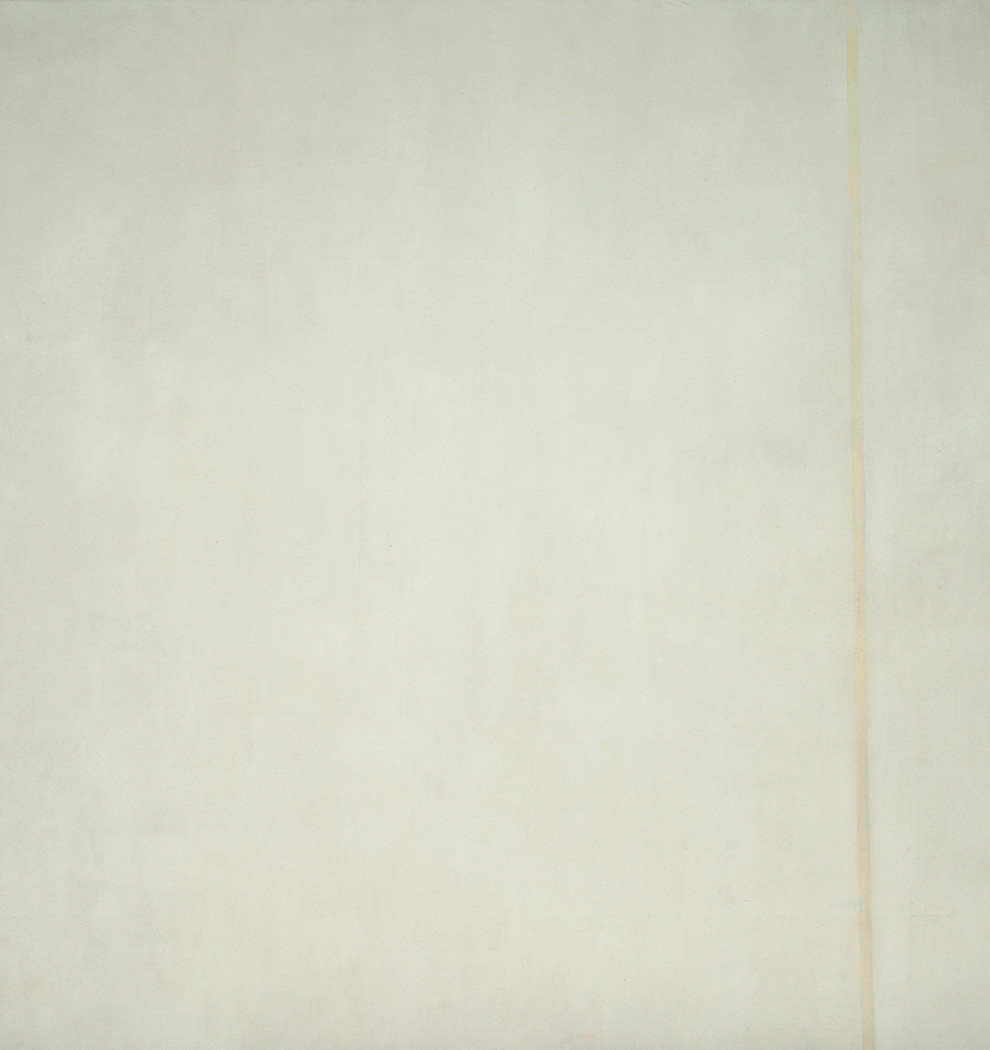

If Sweetser’s account of metaphor assists an interpretation of Newman and Heidegger, it is not simply because one employed physical situations, and other formal relationships on a canvas, to express metaphysical ideas; it is also because both engaged in a strikingly similar kind of etymological study. Both investigated the origins of words, parsed their implications, and claimed to discover more profound layers of meaning in their first incarnations, incarnations where, more often than not, physical situations were described literally. To select the most appropriate title for his signature image (figure 2.1), Newman latched on to the term “Onement,” the archaic version of “atonement.” The choice raises two questions. First, if onement signifies atonement, why use the archaic form? Second, how is the state of atonement communicated by a vertical stripe? Thinking along Sweetserian lines, Newman perhaps judged the older version to convey more concretely how atoning for one’s transgressions is predicated upon being in a state of “harmony” and “wholeness.”1 The older term, in effect, underscores more forcibly the connection between the emotional state of atonement and the physical state of being “one.” Individuals “at one” with themselves live in a state of harmony and commit to the task without reservation. By contrast, a person conflicted or shaken by doubt may atone in a hollow and disingenuous way. Genuine atonement thus requires “harmony,” “wholeness,” and “oneness.” Accordingly, the unitary vertical stripe in Onement I, though frayed and fragile, echoes the posture of an upright, resolute, and unconflicted human being. Standing out dramatically against its darker background, it serves, or so Newman reasoned, as an appropriate form upon which he could project his view of the resolve with which one must approach the act of making amends.

Figure 2.1. Barnett Newman, Onement I (1948), oil on canvas and oil on masking tape, 27.25 3 16.25 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Annalee Newman © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Relying on an older archaic term is no isolated incident in Newman’s work. Though displaying none of the academic self-consciousness of present-day linguists, Newman also stressed how language enlists physical activities to describe intellectual concepts: “The word ‘critic’ comes from the Greek and it means to separate. In art criticism, I suppose the problem is to separate the good from the bad.”2 Like Sweetser, Newman insinuates that conjuring the intellectual activity of criticism is contingent upon, and was extrapolated from, the physical activity of separating objects from one another. Intriguingly, Heidegger also believed that the etymological origins of words betray more profound meanings, and even mentioned the very same term chosen by Newman: “What does ‘critique’ mean? The word comes from the Greek [for] ‘to separate,’ that is, to set something off from something—in most cases something lower from something higher.”3 Heidegger equally acknowledged that the term “meta-physics” denotes a form of inquiry that goes “trans, beyond—what-is as such. Metaphysics is an enquiry over and above what-is.”4 Such observations are pervasive in Heidegger; William Lovitt remarked how replete his philosophical terminology is with words that convey strong spatial connotations (“into,” “from,” “out of,” “toward,” “forth,” and “hither”).5 Yet Newman and Heidegger were not satisfied with exposing links between physical and intellectual situations in language; to their minds, tracing words back to their first incarnations revealed meanings whose power and profundity were gradually being eroded—what Theodor Adorno called “the silent identification of the archaic with the genuine.”6 We cannot understand the word “to build,” Heidegger claims, without realizing that, in Old High German, the word originally meant “to dwell”—namely, “to remain, to stay in place.” The proper meaning, the philosopher professes, is “lost to us.”7 These original implications disclose an order of experience (i.e., dwelling, feeling at home, being comfortable) appropriate to buildings as opposed to other objects, and although all manner of objects exist in space, it is only inside buildings that human beings can legitimately be said to dwell. This is the very kind of originary meaning, lost over time, which Newman’s and Heidegger’s employment of archaic expressions are ostensibly attempting to recover. For Heidegger, losing cognizance of fundamental meanings has a host of unexpectedly dire consequences. “[W]ords are constantly thrown around on the cheap,” he insists, “and in the process are worn out.”8 When the Greek word physis (the existent) is translated as “nature” (from the Latin natura), Heidegger sees the original meaning “thrust aside,” the philosophical force of the Greek word “destroyed.” Far from “harmless,” the mistranslation “marks the first stage in the process by which we cut ourselves off and alienate ourselves from the original essence of Greek philosophy.”9

Greater sensitivity to the earliest meanings would, or so he believed, counteract this alienation and bring us closer to the essence of things. Given Newman’s own references to etymological origins, one suspects that his own employment of “onement” served a similar purpose: to convey steadfastness and resolve more poignantly than “atonement.” Newman also referenced archaic terms while expounding on his architectural designs. A synagogue, he contends, “is more than just a House of Prayer. It is a place, Makom, where each man may be called up to stand before the Torah to read his portion.”10 The purpose of Newman’s art was to create, not just a physical environment, but a place where one knows where one stands and acknowledges one’s responsibilities. How this process comes about is not exactly clear, but notice how rituals transform a synagogue into something more than just a physical location, just as dwelling in a home makes it more than a physical site. Similarly, Newman hoped the reddish, vertical line in Onement, standing dramatically against its dark background, would visualize the unity and resolve necessary to atone, a state of mind comparable to a sense of responsibility—a pledge—before whom one stands. Reading “one’s portion” before a congregation (or before God) also requires clarity of purpose, a sense of conviction comparable to the one with which individuals atone for their sins. The image of a standing human being reciting the Torah, endowed with the harmony and wholeness conveyed by the term “onement,” thus connotes the concentration of a solitary person, standing before all, engaging in a symbolic ritual. On one level, of course, the act of standing simply describes a physical posture (“he stands by the door” or “we stand in line”), but expressions such as “stand up and be counted,” “I stand by what I said,” or “stand for something” identify distinguishing traits of character, traits that separate certain individuals from others, no less than objects that “stand out” are distinguished from their surroundings. Newman, it seems, did not simply wish to portray an image of wholeness or oneness, he wanted his spectators to feel whole, to be at one with themselves, just as a person does while atoning or standing before a congregation. As Gottfried Boehm has it, Newman’s work “is an appeal to viewers: they are told to stand up, to hold themselves upright.”11

The image of the human being “standing out” also appears in Heidegger, though the point of reference is not Judaism but Greek philosophy (of which, as we shall see, Newman was equally fond). Newman, in fact, discerned compelling parallels between Greek and Judaic ideas.12 Our tragedy, he wrote, is one “of action in the chaos that is society (it is interesting that this Greek idea is also a Hebraic concept).”13 Although we will encounter the concept of tragedy and the individual’s relationship to society in later chapters, this quote is cited at this point to intimate that Newman would have detected no contradiction between the Jewish idea of Makom and what Heidegger was extrapolating from Greek philosophy. The interconnections between standing, speaking, and emotional togetherness specific to Newman’s description of a person reading the Torah also closely align with Heidegger’s analysis of logos. While the Greek term is mostly associated with verbal expression, Heidegger argues that logos originally did not refer to speech.14 Presenting a rather idiosyncratic reading, and recalling the configuration of Onement, Heidegger insists that logos is actually “the intrinsic togetherness of the essent. . . . Logos characterizes being in a new and yet old respect: that which is, which stands straight and distinct in itself, is at the same time gathered togetherness in itself and by itself, and maintains itself in such togetherness.”15 Words such as “gathering” and “togetherness” are significant for Heidegger because Being maintains “in a common bond the conflicting and that which tends apart.” Instead of allowing things to “fall into haphazard dispersion,” the logos sustains bonds, and “does not let what it holds in its power dissolve into an empty freedom from opposition, but by uniting the opposites maintains the full sharpness of their tension.”16 To apprehend truly, the philosopher continues, means “to let something (namely that which shows itself, which appears) come to one. . . . Unity is the belonging-together of antagonisms. This is original oneness.”17

Heidegger’s account of logos parallels the meanings underlying Onement. Our humanity is apparently keenest when we stand by ourselves, gathered and resolved in unified togetherness. The ancient Greek term for being resolute, for being decided, Heidegger adds, has another meaning as well: “‘de-cision’ means to be without a scission from Being.”18 The implication, then, is that in decided resolution, we come closer to Being, to the meaning of existence. It is important to note, however, that, even if “atonement” bespeaks an act to be approached without reservation, as well as a connection to existence, this hardly implies a complete elimination of tension and complexity, only a “belonging-together of antagonisms.” In its original sense, oneness is not complete uniformity, but a unity, even a unity of disparate parts. A sincere act of atonement would be meaningless, after all, if no ethical tension or psychological stress were in need of atonement. Even so, we atone in a more meaningful and authentic way when, despite our conflicts, we achieve the condition of oneness, explaining Newman’s preference for the archaic “onement.” If these were indeed his motivations, his reasoning would not be far from Heidegger’s, a thinker who believed that the abuse of thought is “overcome only by authentic thinking that goes back to the roots—and by nothing else.”19

Heidegger even sharpened his inquiry by turning it on itself. By seeking the origin of the very word “origin,” Heidegger discerned how the physical situations evoked by this term uncovered another layer of meaning. As Steiner observed, in German, the word for “origin” or “source” is Herkunft—“literally the place from which we came, the ‘provenance of our coming.’” Related terms such as zurückgerufen and re-klamiert, according to Steiner, carry a physical edge: “There is a ‘re-vocation,’ a ‘summoning back to’ the place of our inception and insuration.”20 The story does not end there; by unearthing the first meanings of “origin,” and by pondering their literalist implications, Heidegger pressed the claim that “the origin of something is the source of its essence.”21 The first meanings, in effect, do not simply enrich our understanding of certain words or concepts—they betray a primordial kernel of reality no longer accessible to us. This explains Heidegger and Newman’s attention to beginnings. While attending to “the early meaning of a word and its changes,” Heidegger posits, we apprehend “that essential realm as the one in which the matter named through the word moves. Only in this way does the word speak, and speak in the complex of meanings into which the matter that is named by it unfolds throughout the history of poetry and thought.”22 If one accepts this reading, then, in employing “Onement,” Newman is saying that the essence of atonement, and, perhaps, of the human being itself, lies in being “one.”

It should be interjected, if only parenthetically, that, in the field of linguistics at least, few contemporary scholars would conflate origins with essences. For Sweetser, etymological research revealed the bodily basis of meaning, not the essence of things; Heidegger and Newman may have taken this connection for granted, but it hardly qualifies as an “objective fact” of linguistic analysis. All the same, this prevented Heidegger neither from putting his own interpretive spin on etymological investigations (i.e., associating origins with essences) nor from claiming these essences to contain hermetic layers of meaning that, lost in modern times, are in urgent need of recovery. To his mind, it followed that investigating how human existence was originally conceptualized would also uncover its essence: “Every doctrine of Being is in itself alone a doctrine of man’s essential nature.”23 Newman felt the same way. When he spoke of “man’s birthright, his urge to be exalted,” he described human nature in quasi-Heideggerian terms—namely, as something that “even primitive man understood and which modern man seems to have forgotten.”24 In effect, Heidegger and Newman are implying that, unlike “primitive man,” modern humans have forgotten their own essence. Accordingly, Newman praised pre-Columbian sculpture, and the originary character of non-Western art in general, for employing an “abstract quality of formal relationships” that “tells us more of man’s nature than a naturalistic representation of man’s physical contours.”25

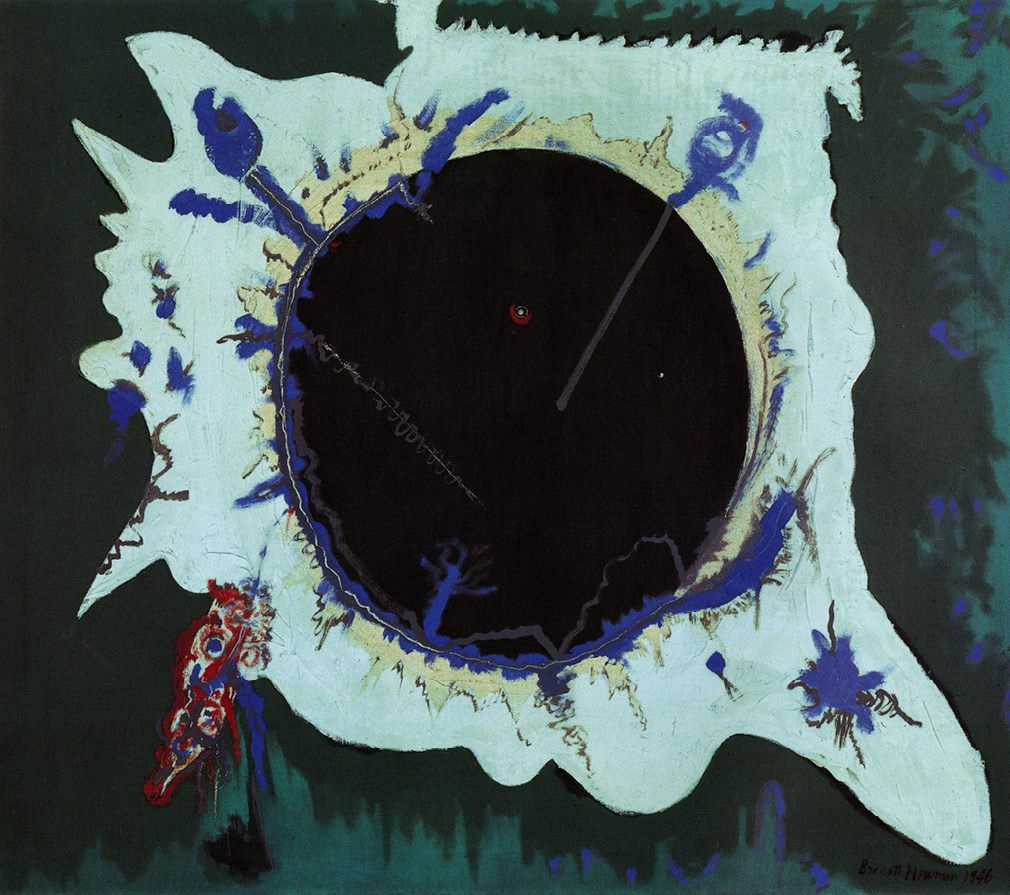

Not simply an attempt to exhume obscure terms (as could be said of “onement,” or of Heidegger’s employment of the archaic Seyn instead of Sein26), the recovery of origins provided a means of grasping essences lost to modern individuals. “Essential thinking,” Heidegger contends, “must always say only the same, the old, the oldest, the beginning, and must say it primordially.”27 Instructively, the connection between origin and essence pertains as much to the actual content of Heidegger’s philosophy and Newman’s art as to the means both men employed to arrest or forestall the erosion of meaning. That content was the birth of things: of language, thought, matter, and humanity itself. Revisiting the competitive analogy between artistic and divine creation voiced by Renaissance artists, Newman evoked the biblical account of the earth’s creation in paintings such as Genesis—The Break (figure 2.2) and Pagan Void (figure 2.3), or of God’s separation of light from darkness in The Beginning (figure 2.4) and Moment (figure 2.5). Neither the imitation of natural forms nor the idealized representation of human beings made in God’s image held any interest for Newman. Instead, he focused on God’s first acts: the emergence out of nothing of light, form, and substance—entities that, by virtue of being somewhat nebulous, required an abstract formal language. Just as Heidegger assumed that the origin of a word betrayed its essence, so did Newman believe that these images—by emulating God’s creative inventions and conveying the first manifestations of light and matter—would, by analogy, evoke the beginnings (and essence) of creativity itself. “In 1940,” he wrote, “some of us woke . . . to find that painting did not really exist. . . . It was that awakening that inspired the aspiration . . . to start from scratch, to paint as if painting never existed.”28 As late as the 1960s, he still insisted on starting each piece as if he had never painted before.29 Only by wiping the artistic slate clean, as it were, could Newman capture, or so he believed, the essence of art.30 By bringing the artist “back to first principles” and rediscovering “the original impulse,”31 modern art would express “important truths.”32

Figure 2.2. Barnett Newman, Genesis—The Break (1946), oil on canvas, 24 27 1/8 inches. Dia Center for the Arts, New York © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 2.3. Barnett Newman, Pagan Void (1946), oil on canvas, 33 38 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Gift of Annalee Newman © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

To transcribe so primordial a subject as Genesis, and make his images appear as if nothing even remotely comparable had hitherto been created, Newman simplified his visual language and ignored artistic precedents. Ironically, as he admitted himself, approximating the “original” impulse mandated a completely “new” aesthetic. To simulate “the living quality of creation,” Newman reasoned, “new forms and symbols” were required.33 The quest for origins, then, was more a question of inventing original stylistic solutions than the retrieval of something antecedent. Whether Newman noticed this paradox is impossible to say; perhaps he assumed that, just as God’s creations were wholly original, given that they brought the universe into being, his own emulations of God’s actions had to follow suit. If so, his attitude closely follows Heidegger’s view that the very asking of the question of Being means nothing less than recapturing and repeating “the beginning of our historical-spiritual existence, in order to transform it into a new beginning. . . . But we do not repeat a beginning by reducing it to something past and now known, which need merely be imitated; no, the beginning must be begun again, more radically, with all the strangeness, darkness, insecurity that attend a true beginning.”34 The only way to preserve the power of this beginning, Heidegger continues, “is to repeat it, to retrieve it once gain . . . in its original character, in a more originative way.”35 Newman and Heidegger could not be any closer. If the modern artist can conjure “the ordered truth that is the expression of his attitude towards the mystery of life and death, it can be said,” Newman proclaimed, “that the artist [is] like a true creator . . . for the Creator in creating the world began with the same material.”36 By referencing the subject matter of Genesis, the extreme economy of his designs bespeak Newman’s own attempt to repeat the beginning, to recover how God’s act of bringing the world into being conflates the birth of the world with the beginning of creativity.

Figure 2.4. Barnett Newman, The Beginning (1946), oil on canvas, 40 29.75 inches. Art Institute of Chicago. Through prior gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison, 1989 © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Given his philosophical interests, it would not be long before Newman shifted his attention to God’s most significant creation: humanity. This orientation re-aligned Newman’s work with what he claimed was the subject of his art: the nature of the self and the plight of the human condition. Genesis provides the appropriate reference point: Adam (figure 2.6), and perhaps Onement as well, evokes God’s creation of man out of clay.37 As Newman himself put it, “my work, although it’s abstract . . . is involved in man.”38 And in keeping with his interest in the etymological origins of words, Newman mused, “The first man was called Adam. ‘Adam’ means earth but it also means ‘red.’” 39

Figure 2.5. Barnett Newman, Moment (1946), oil on canvas, 30 16 inches. Tate Gallery, London. Presented by Mrs. Annalee Newman in honor of the directorship of Sir Alan Bowness, 1988 © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Is Newman’s point to represent Adam by a red stripe? Yes. Harold Rosenberg, a friend of the artist, related how the “isolated vertical stands for the self and for the first, for the conferring of meaning and the origin of substance.”40 As Bois has also observed, the stripe, bilaterally symmetrical, refers “directly to our body structure and to the way we, as humans, organize our perception of the world.”41 Such an act of projection, even on so schematic an image, would have been child’s play for Newman. Human beings, after all, frequently project the structure of a human body on inanimate objects (e.g., the “face” of a clock or the “back” of a chair). A Newman canvas, David Sylvester adds, is also “rigorously related to human scale. Thus we mentally measure the distances between its verticals in terms of the span of our own reach—by stretching out our arms in imagination, in judging how far they have to be stretched out in order to span that interval.”42 The stripe, then, is meant to refer, on a basic level, to God’s creative act: his own decision to differentiate humanity from the inanimate matter of the earth. Interestingly, Philip Guston (figure 2.7) painted a strikingly similar theme, with—presumably—the hand of God breaking from a menacing cloud to delineate a characteristically Newmanesque line on an expanse of earth. Less literal than Guston, Newman omitted the overpowering presence of the Creator altogether, perhaps because he deemed its inclusion too obvious and therefore unnecessary, or perhaps because he wanted to usurp the place of the Creator himself—an “immodest” and un-Jewish ambition, according to Matthew Baigell.43 Indeed, when compared to The Line, Onement gives the impression that the human presence has neither history nor precedents, that it could have emerged ex nihilo, of its own accord, independently, and without the approval, of a divine intercessor. By asserting its autonomy on its own terms, Newman’s line forms a breach, an “irruption” of existence—of Being among beings, as Heidegger would voice it.44 It is also a demarcation point: it is set and sets itself apart; in coming into Being, it announces its difference from its surroundings, implying, in no uncertain terms, that humanity is qualitatively distinct from the rest of creation.45 Newman’s passages cited above—praising non-Western art for employing an abstract quality that “tells us more of man’s nature than a naturalistic representation of man’s physical contours,”46 and criticizing Western art for diluting the reality of “man’s nature” in favor of a shallow and overly sensual illusionism—reinforce a reading of Adam and Onement as representing the essence of humanity as the artist understood it.

Figure 2.6. Barnett Newman, Adam (1951, 1952), oil and magna on canvas, 95 5/8 79 7/8 inches. Tate Gallery, London © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 2.7. Philip Guston, The Line (1978), oil on canvas, private collection (see McKee Gallery, New York).

Heidegger would have concurred; the point of art, he argued, “is not the reproduction of some particular entity that happens to be present at any given time; it is, on the contrary, the reproduction of the thing’s general essence.”47 But if the purpose of art is to reproduce man’s essence, what does this essence consist of? If Newman’s own statements provide any indication, that essence is to be a creator. “What was the first man,” he pondered, “was he a hunter, a toolmaker, a farmer, a worker, a priest, or a politician? Undoubtedly the first man was an artist.”48 Newman’s claim, of course, is hyperbolic, even slightly outrageous—a thoroughly “romanticized anthropology” as Charles Harrison put it49—if only because there is no possible way of corroborating its veracity. Perchance the statement was not meant too literally. Inasmuch as Heidegger singles out humanity as the only species that does not simply exist, but questions its existence (intimating, as Newman did in his own domain, that the first man was a philosopher), Newman singles out humanity as the only species that creates art. “Just as man’s first speech was poetic before it became utilitarian,” he writes, “so man first built an idol of mud before he fashioned an ax. Man’s hand traced the stick through the mud to make a line before he learned to throw the stick as a javelin. . . . The artistic act is man’s personal birthright.”50

We may be forced to forgive Heidegger and Newman for ascribing priority to their respective fields, but Newman’s statement is not quite as farfetched as it may seem. Present-day evolutionary biologists argue that the physical dexterity necessary to wield a stick and draw a line is a direct consequence of our upright posture; if our hands still had to bear part of our weight (as is the case for chimpanzees or gorillas), this ability would not have evolved. Analogously, while Neanderthals used tools, and lived at the same time as modern humans, they did not create art; nor did they decorate their dead or bury them in complex constructions.51 It is the consensus among present-day anthropologists, moreover, that nearly all cultures create some form of art and music, perhaps the direct outcome of the significant brain differences of modern humans, evolutionary changes that spawned hitherto unseen abilities: to invent, to use language with complex vocabularies, and to symbolize cultural hierarchies in the form of ornaments. If these activities do mark the arrival of a new species, then Newman’s admittedly highfalutin statement is not quite as ridiculous as it sounds. If art and creativity are unique to us, then it stands to reason that these very same abilities help us define and express who we are. From this perspective, Newman’s sentence could conceivably be recast to mean, not that the first man was literally an artist, but the first hominids to create art were modern humans, not Neanderthals.52 Heidegger came to analogous conclusions. “Apes, too, have organs that can grasp,” he observed, “but they do not have hands. The hand is infinitely different from all grasping organs—paws, claws, or fangs—different by an abyss of essence. Only a being who can speak, that is, think, can have hands and can be handy in achieving works of handicraft.” The human hand, he continues, “receives and welcomes—and not just things: the hand extends itself, and receives its own welcome in the hands of others. . . . The hand designs and signs, presumably because man is a sign. . . . All the work of the hand is rooted in thinking.”53

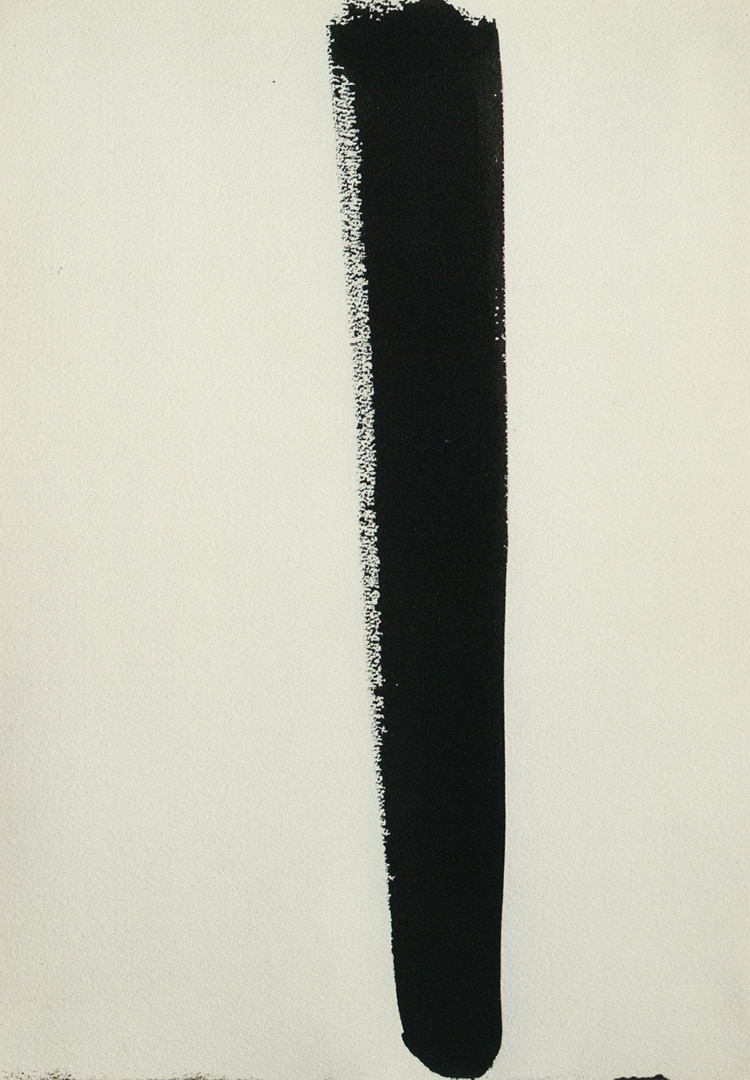

Along these lines, just as God’s creation of the world brought matter and, ipso facto, creativity into existence, the vertical stripe in Adam references both the divine act of creating man out of clay, and the self-definitive human creative act of tracing a line on the earth. The correlation between an image of the first man and the first image created by him, in turn, converge to reinforce Newman’s belief in creativity as humanity’s “personal birthright,” the privileged activity that defines the essential nature of human beings. Hence, drawing a line denotes both humanity’s ability to create something non-utilitarian, and, in the process, its urge to depict, and thereby define, itself. It is this assumption, arguably, that underlies Newman’s insistence on non-Western art’s capacity to reveal more of “man’s nature” than other, illusionistic forms of representation. Of course, we cannot verify whether Newman had a rectilinear line in mind (rather than a curve, a zigzag, or a geometrical form) when he exclaimed that man used a stick to draw a line before throwing a javelin. But it is tempting to propose that he envisioned his original Adam tracing a line not unlike those in his own work: clear in its directionality, and vertical in its echo of the human being standing upright and self-aware before the vast immensity of nature.54 The unusually gestural Untitled (figure 2.8) reinforces such a reading, conflating in a quick stroke both the primordial creative act of drawing a line and the upright posture of a human being. Recapitulating humanity’s first foray into creativity was thus no different from tracing the origin of verbal expressions to their most fundamental meanings: in this case, Newman’s work yielded an image both simple and complex, one that would simultaneously visualize primordial humanity’s “oneness” as well as stress how exclusive creativity was to its innermost nature. (Not surprisingly, the verbal expression “a line has been drawn” means making absolute and unbridgeable distinctions.)

Figure 2.8. Barnett Newman, Untitled (1960), brush and ink on paper, 14 10 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Annalee Newman © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

As intrigued with beginnings as Newman, Heidegger wrote that endemic to fields such as ethnology and anthropology is the basic fallacy “that history begins with the primitive. . . . The opposite is true. The beginning is the strangest and mightiest. What comes afterward is not development but the flattening that results from mere spreading out; it is inability to retain the beginning.”55 Consonant with Newman’s ambition to work as if painting never existed before, many of Heidegger’s lectures were published under rubrics that betray his belief in the primary nature of his philosophy: Basic Concepts, Introduction to Metaphysics, The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics, The Basic Problems of Phenomenology. These texts are not basic in the sense of providing introductory remarks, but in the sense of outlining what Heidegger considers the very ground of these modes of questioning. In Being in Time, he expressed his contention that the most significant question, the meaning of Being, was not simply inadequately formulated; it was utterly “forgotten.” His work represented nothing less than an attempt to redress philosophy’s complete “neglect of the question of being.”56 Even if past philosophers asked crucial questions about the essential nature of the good, of freedom, of truth, and so on, these questions—if recast in the form of what does it mean to be moral, to be free, or to be authentic—reveal, as Michael Gelven succinctly put it, that in all the ways we exist or act, “it is possible to reformulate the question so that the infinitive ‘to be’ becomes the unifying and underlying question.”57 The nature of Being, the philosopher asserts, is the “essential question.”58 Inasmuch as Newman urged modern artists to return to “first principles,”59 Heidegger engaged what he considered the most fundamental, primary problem of philosophy: what does it mean to exist at all? Long before another thinker, he was fascinated with what the meaning of is is. Rescuing this question from oblivion was tantamount, Heidegger believed, as Newman did in his own domain, to creating a “first philosophy.”

Both Newman and Heidegger seem to share the view that the meaning of existence is discerned most poignantly at its very beginning, when the distinction and contrast between it and nonexistence is most keenly manifest. Both Genesis—The Break (figure 2.2) and Moment (figure 2.5) visualize such a contrast: when matter suddenly erupts out of chaos, or when intense light abruptly overwhelms the darkness. In the gap between Being and non-Being, Heidegger writes, “the transition from one side to the other is ‘sudden;’ it takes only a moment and is over in a trice.”60 If Being shows itself, it does so “only ‘suddenly’. . . the way something irrupts into appearance, from non-appearance.”61 The myth of creation, he surmises, “does not tear away from concealment something unconcealed but speaks out of that region from which springs forth the original essential unity of the two, where the beginning is.”62 On one level, of course, Newman’s images refer to the theme of divine creation mentioned above, but in view of his self-proclaimed interest in humanity, the intensity of the moments when the distinction between light and dark, form and chaos are at their sharpest—when the essent comes into Being—could also be interpreted as referencing the distinction between self-awareness and lack thereof.

A similar metaphor underlies some of Heidegger’s interpretations of poetry. The philosopher reads Hölderlin’s term “homecoming” as a return to “the source.”� For Heidegger, “homecoming,” “homeland,” or a “return to the source” have, as will be discussed later, nationalistic connotations; figuratively speaking, they also signify a “nearness to Being.”64 Returning home, in this sense, means returning to the question of existence, or, more accurately, to a state of mind preoccupied with that question. Since Newman’s images focus on moments when entities such as light, matter, and humanity burst into Being, they were meant to function, analogously, as triggers to the contemplation of what it means to exist. By depicting the first manifestations of things, Newman was “returning home” in Heidegger’s sense of the word: he was not simply portraying a schematized, vertical Adam against the formless clay from which he was extracted; he was evoking the spark of self-awareness that overcomes humanity at the very moment it emerges from a state of nonexistence: man, Newman declared, “can be or is sublime in his relation to his sense of being aware.”65 To the same extent that a burst of light appears the sharper at the very moment it dispels the darkness, Newman’s Moment (figure 2.5), arguably, represents an instant of greatest intensity, when self-consciousness all the more powerfully differentiates the human from the nonhuman. Accentuating the contrast between the beam and the field, Newman’s gestural marks insinuate that the background is formless, heterogeneous, and indefinite, in direct opposition to the clarity, homogeneity, and definition characteristic of the central form. By returning to beginnings, we are made self-aware, and come closer to Being.

If Newman thought the first man was an artist—or, more precisely, that humanity’s nature lies in being creative—Heidegger thought, as intimated above, that humanity’s nature lies in being thoughtful: “What is man? . . . We do not know. Yet we have seen that in the essence of this mysterious being, philosophy happens.”66 Inasmuch as Newman viewed the artistic act as “man’s personal birthright,” Heidegger viewed philosophizing as “fundamentally belong[ing] to each human being as something proper to them.”67 It is philosophy, according to Heidegger, that lets human existence first “become what it can be . . . philosophizing is something that lies prior to every occupation and constitutes the fundamental occurrence” of human existence.68 Thinking, Heidegger asserts, is “the dowry of our nature.”69 Philosophy happens in man because man is the only being who can interrogate his own existence, just as art, one may argue, is man’s birthright because man is the only creature that creates.

Art and philosophy converge not only because Newman sought to raise art to the level of philosophy, and Heidegger philosophy to that of poetry, or because both men saw these activities as originary, but also because painter and philosopher connected them to another exclusively human condition: freedom. For Heidegger, affirming one’s existence is inextricable from having freedom of choice: “The affirmation of human existence and hence its essential consummation occurs through freedom of decision.”70 This view dovetails nicely with Newman’s own assertions: first, that “man is sublime only insofar as he is aware”; second, that the artist “is free and insists upon freedom.”71 If recovering the essence of humanity reveals anything for Newman and Heidegger, it is how intimately we are defined by our affirmation of our own existence and our freedom of choice.

We shall return to the question of freedom in a later section; for now, it is significant to iterate that, just as freedom of decision stems from self-awareness, it also makes existence burdensome. Newman’s connection of man to the earth (“Adam means earth”), for example, is consistent with Heidegger’s question (“What must man affirm?”) and reply (“That he belongs to the earth. This relationship of belonging consists in the fact that man is heir and learner in all things. But these things are in conflict”).72 The passage is difficult to interpret because Heidegger’s employment of “earth” was seldom consistent. In “The Origin of the Work of Art,” he made the distinction between “earth” and “world” (the realm of concealment versus the realm of meaning and unconcealment); in a later essay, “The Thing,” Heidegger made a different, fourfold distinction between “earth” and “sky,” “gods” and “mortals.” In “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry,” the essay from which the above citation about man “belonging to the earth” derives, no such polarities are drawn. Whether Newman could successfully navigate the shifting nuances and subtleties of Heideggerian terminology is impossible to say; regardless, it is likely that he would have appreciated any philosophical position that, with a modicum of tweaking, could be made to reinforce his own. Heidegger’s proposition that man’s belonging to the earth is in conflict with his being heir and learner in all things is echoed in a point Newman made while reviewing the exhibitions of fellow painters Adolph Gottlieb and Rufino Tamayo, although one cannot escape the suspicion that Newman, as is often the case, was actually describing the ideas underlying his own work. Gottlieb and Tamayo, he writes, succeed in expressing man’s “earthly ties and natures. In so bringing us down to earth they confront us with the problems of man’s spirituality.”73 The conflict Heidegger mentions between man’s belonging to the earth and being heir to all things—and Newman between “our earthly ties” and our “spirituality”—recalls the age-old distinction between body and soul. Newman and Heidegger, however, have something altogether different in mind. Heidegger often asserted that self-awareness and freedom of choice define who we are as much as provoke a sense of rivalry with God. By reenacting the primordial creation performed by the gods, the poet enters in proximity and competition with the divine.74 Man, according to Heidegger, “has always measured himself with and against something heavenly.”75 This issue resonated with Newman, since he construed the relationship between humanity and the divine as frayed by conflict. Although he showcased art as evidence of humanity’s emulation of things godly, Newman ups the ante by painting God as jealous of this same emulation: “It was inconceivable . . . that Adam, was put on earth to be a toiler, to be a social animal. . . . The fall of man was understood by the writer [of Genesis] and his audience not as a fall from Utopia to struggle. . . . But rather that Adam, by eating from the Tree of Knowledge, sought the creative life to be, like God, a ‘creator of worlds’ . . . and was reduced to the life of toil only as a result of a jealous punishment.”76

Similarly, Heidegger saw the poet as the greatest human pretender to divine status, an intermediary between gods and men. He even refers to the poet as the “demi-god” or as “the pointer.” Above men but below gods, poets and artists cannot assume this standing without being overcome by dangerous feelings of rivalry and jealousy. “All too easily could the demigod,” Heidegger writes, “pushed out above men, not want to endure his inequality to the gods . . . and so at the same time wrongly measure himself by the standard of human beings. Too easily can the demigod . . . be too desirous to become one of them. Thus his own being, carried away by the one (to be a god or to be human), can fall into division and be thrown into doubt.”77 Aspiring to, yet not being able to achieve, divine status, the artist is set apart from the gods as much as from the rest of humanity. Heidegger even posits that gods and men were separated “in polemos, in the conflict which sets (being) apart. It is only such conflict that . . . shows, that brings forth gods and men in their being. We do not learn who man is by learned definitions; we learn it only when man contends with the essent, striving to bring it into its being . . . that is to say when he projects something new (not yet present), when he creates original poetry, when he builds poetically.”78 As new things come into being, Being itself is split apart, bestowing form and shape upon beings. When humanity is creative, something analogous happens: the conflict separating the human from the divine becomes palpable, and humans and gods appear as what they are.

It is likely that Newman subscribed to this point of view. Newman’s “first move,” according to Thomas Hess, “is an act of division . . . a gesture of separation . . . a line drawn in the void.”79 Like Heidegger, he cast the desire to create as a distinguishing feature of humanity, no less than its unique level of self-awareness, its possession of freedom of choice, and its proclivity to affirm its existence. Yet both men would have asserted that the very qualities that distinguish human existence also make it oppressive. In making art, we bring something new into the world; we contend, as Heidegger would put it, with the essent: we reflect our creative nature and affirm that we exist. By sparking a collision between human and divine wills, however, creativity also tempts humanity—or, rather, the artists and poets—into mistaking their place in the sanctioned order of things. Unable to reconcile these tensions, artists experience their existence as tragic; neither worldly nor godly, they belong nowhere. As Hess reads Newman, our experience is one of separation, as if cast out into a void. Even so, the tragedy we inherit, despite its vicissitudes, is the only form of existence there is. Our responsibility is to affirm it in the most powerful way possible, and art, for both Newman and Heidegger, represents the most emphatic means of doing so. Just as Newman prized experiences that provoke “a heightened sense of ‘being,’”80 the beauty of poetic art, Heidegger proclaimed, evokes “the enduring presence of Being.”81 When Heidegger asked the question, “Who then is man?,” he provided the following answer: “He who must affirm what he is. To affirm means to declare, but at the same time it means: to give in the declaration a guarantee of what is declared. Man is he who is, precisely in the affirmation of his own existence.”82 Thus, if the creation of art, for Newman, distinguishes what is human, for Heidegger, it is the affirmation of existence.

If some experiences arouse “a heightened sense” or the “enduring presence” of Being, others betray its absence or oblivion. Newman did not simply paint works such as Moment or Adam, which convey the coming of light or man into existence; he also painted Day Before One (figure 2.9) or Pagan Void (figure 2.3), ostensibly to evoke a moment of limbo, a time prior to the creation of the universe, before humanity understood its own nature and rivaled the divine. From a Heideggerian perspective, these paintings could be interpreted as evincing a state where Being is not yet manifest. This may sound contradictory, but Heidegger’s view of Being is very close to Newman’s of man being sublime only insofar as he is aware. 83 For Heidegger, Being is not an either/or proposition (i.e., one exists or one does not) but a qualitative condition: as different ways of Being exist, there can be more or less Being. When we marshal our spiritual powers, the existent comes into the open: “Where spirit prevails, the essent as such becomes always and at all times more essent.”84 “Beings are more in being the more present they are,” he adds. “Beings come to be more present, the more abidingly they abide.”85 Conversely, if we fail to ponder spiritual questions, we aid and abet the forgetfulness of Being.

Figure 2.9. Barnett Newman, Day Before One (1951), oil on canvas, 132 50 inches. Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel. Gift of the Swiss National Insurance Company © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When human beings understand who they are, their existence becomes more essent.86 At that point, a human being becomes a Da-sein (human existence). Although we will return to and define this concept in a later chapter, for now suffice it to say that Heidegger insisted not only that an understanding of Being belongs to Da-sein but also that this understanding “develops or decays” according to our manner of Being.87 This is why Newman’s phrases, “a heightened sense of ‘being’” or that man is sublime in relation to his “being aware,”88 closely parallel Heidegger’s point of view. As it is incumbent upon humanity to think, thought remains particular and exclusive to us; thinking, in Heideggerian parlance, is “ownmost” to humanity. Yet as only human beings think, only human beings turn away from thought. By indulging our ability to think, we are true to our nature and yet, Heidegger laments, “man flees from what is ownmost to him.”89 Likewise, Newman intimated that human beings are not permanently sublime; if they were, the word would carry no meaning, implying that human beings are mostly oblivious, a charge that Newman launched, conveniently, at anyone who failed to appreciate his worthiness. Having failed to pass a teacher’s qualification exam, he challenged the decision by arguing that the hiring criteria should permit “unusual” and “inspiring” individuals to “train children to become thinking people.”90 Again, the implication is that the majority of human beings are un-thinking, a position that coincides with Heidegger’s proclamation that “what is most thought-provoking” is “that we are still not thinking.”91 “[T]he involvement with thought,” he continues, “is in itself a rare thing, reserved for few people.”92 The condition of Da-sein defines precisely the opposite.93 Heidegger could not have put it more bluntly: man “is the being who is insofar as he thinks.”94

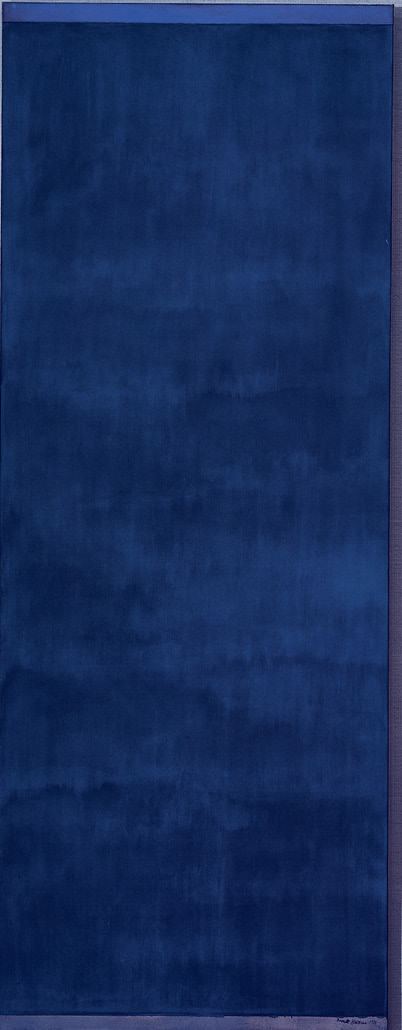

Newman’s connection between sublimity and awareness, and Heidegger’s between Da-sein and awareness of Being, deepen our reading of Newman’s Onement I (figure 2.1) and, arguably, of Be (figure 2.10). To the oneness of human atonement, and to Heidegger’s concept of the unity of Being, one can add the link between Being and apprehension. Where Being prevails, Heidegger insists, apprehension prevails with it: “the two belong together. . . . But if man is to participate in this appearing and apprehension, he must himself be, he must belong to being.” Apprehension, the philosopher concludes, “determines the essence of being-human.”95 Newman’s Be stands as a kind of imperative: “exist.” But, if read through a Heideggerian prism, it also means “think.” For Newman and Heidegger, only a sophisticated kind of awareness—one that transcends conventional knowledge or logic—leads to understanding and reflection.96 And depending on the profundity of this understanding, the manner and quality of our Being increases or decreases. If the beam in Be looks narrow, fragile, frail, and delicate, it compensates for these deficiencies by shining brightly, standing out from its surroundings even more dramatically than its counterpart in Onement. If the overall meaning of both pieces is similar, their effect is different—not in kind but in degree. The beam expands or contracts, brightens or darkens, in keeping with the intensity of our awareness. Works such as Pagan Void (figure 2.3) or Day Before One (figure 2.9), conversely, represent a state of physical chaos, a chaos, when understood metaphorically, analogous to a state of non-Being or non-awareness, or even a state wherein Being is undergoing a process of concealment and forgetfulness. This explains why themes of creation were so important to Newman: they could visualize the coming into existence, not simply of matter, light, or of man as a physical entity, but also the contrast between ignorance, stupor, and oblivion versus awareness, assertion, and sublimity.

Figure 2.10. Barnett Newman, Be I (1949), oil on canvas, 93 1/8 3 75 1/8 inches. The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas. Gift of Annalee Newman © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Since acts of creation also beget acts of naming, Newman’s and Heidegger’s focus on beginnings conflates two issues already mentioned: the use of archaic expressions and the parallel between artistic and divine creativity. For Heidegger, Being is manifest through language; poetry is not imitation, representation, or symbolization, but an act of nomination. By naming, language “brings beings to word and to appearance.”97 Man, Heidegger declares, is “that creature whose being is essentially determined by its ability to speak.”98 That very ability, he asserted elsewhere, “marks man as man.”99 If understanding Being is integral to the human being, expressing what is understood is no less so. Interestingly, Newman employed titles such as The Name (figure 2.11), The Voice (figure 2.12), The Word, or The Command,100 endeavoring to evoke, the artist told T. B. Hess, the “human utterance.”101 In which case, we surmise that Newman, no less than Heidegger, understood language as a declaration of human existence and its drive to create no less than the aesthetic act of drawing a line. His ambition, it seems, was to devise an art form whose references to Genesis might capitalize on this very simultaneity, allowing the beams to stand for a schematic human figure, upright in its stance, affirming its existence in opposition to its surrounding environment, but also for a human utterance, just as we transcribe sound waves and decibels visually in graphs or charts. If so, this conflation comprises another point of intersection between Newman and Heidegger. Being, the philosopher argued, “manifests itself primordially in the word.”102 Language, then, is how humanity responds to Being, and, in turn, how Being discloses itself to humanity. As William Richardson explains, Being “is a process of light. It is aboriginal Utterance, yet never ‘is’ itself a being, hence never can be expressed adequately in the ontic dimension of human language and remains for this reason necessarily unsaid. It shines forth in beings with utter simplicity. It is the One.”103 Analogously, if Newman’s abstract beam represents an aboriginal utterance, its sound does not communicate information, as much as assert that human beings are; it does not compel as much as invite us to ponder the meaning of existence. And unlike transcriptions of sound waves—that oscillate according to different frequencies—Newman’s zips are straight in their orientation and directionality, echoing the gathered collectedness that Heidegger associates with Being. “The word, the name,” the philosopher writes, “restores the emerging entity from the immediate, overpowering surge to its being and maintains it in this openness, delimitation, and permanence. . . . Pristine speech opens up the being of the entity in the structure of its collectedness.”104

Figure 2.11. Barnett Newman, The Name II (1950), oil and magna on canvas, 104 3 94.5 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Gift of Annalee Newman, in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the National Gallery of Art. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

By naming, moreover, humanity establishes a rapport with the entity it names, thereby asserting the existence of both the entity and itself. According to Heidegger, human beings name only those objects with which they establish a relation, by virtue of which they express their concerns and, in turn, aspects of their Being. Without language, he writes, “all essents would be closed to us, the essent that we ourselves are no less than the essent that we are not.”105 The relationships acknowledged through nomination, therefore, reveal humanity’s way of bestowing Being onto an entity and onto ourselves: “It is only the word at our disposal which endows the thing with Being.”106 This does not mean, of course, that Heidegger believes objects in the world only exist upon being named: Whether we ask the question as to why things exist, “the planets move in their orbits, the sap of life flows through plant and animal.”107 Nothing, he insists, is “changed by our questioning. It remains what it is and as it is. Our questioning [or naming] . . . cannot in any way affect the essent itself.”108 Even so, Heidegger proposes, “It is in words and language that things first come into being and are.”109 There is something to what Heidegger is saying. It is easier, after all, to remember objects if we have categories—verbal descriptors—to which we can assign them.110 In that sense, language affects and changes our relationship to objects in the external world. But Heidegger is after something more fundamental. The ancients, he argues, did not learn that physis means the power of the existent to blossom, emerge, and endure “through natural phenomena, but the other way around: it was through a fundamental poetic and intellectual experience of being that they discovered what they had to call physis.”111 It is not, therefore, that a named Beethoven sonata is easier to remember than an opus number, or a plant if one knows its scientific designation; it is as if some underlying primordial poetic knowledge of Being permits us to experience art and nature in the first place. Primordial language holds the power to make the existent manifest.112 For this reason, original names and meanings divulge the nature of our first relationships and underscore humanity’s special status with respect to the question of Being.

Figure 2.12. Barnett Newman, The Voice (1950), egg tempera and oil on canvas, 96 1/8 3 105.5 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (Digital Image © Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York)

Regrettably, modern language has distorted and obscured the deeper meanings of original words, meanings that did not simply mutate, but fell into oblivion. Humanity, the philosopher contends, has barely understood, let alone pondered the mystery by whose process language gradually withdraws from man and falls silent. If the first words coined to name an object or idea reveal its essence, then attending to origins reverses this process.113 Again, Heidegger’s investigation relies on the ways in which physical relationships underlie the logic of metaphorical mapping. Returning to one of the examples already mentioned—of building as dwelling—Heidegger insists that so long as we ignore “that all building is in itself a dwelling, we cannot even adequately ask, let alone properly decide, what the building of building might be in its essence.”114 But Heidegger reverses the terms in Sweetser’s linguistic equation. If she argued that the physical relationships anteceded and underpinned the philosophical ones (e.g., that the erection of physical buildings later engendered the idea of dwelling), Heidegger posits the opposite view: that the idea of dwelling antecedes and underpins the essence of building.

Working under the assumption that original linguistic designations disclose essences, Heidegger reasoned that the earliest designations of the concept most important to him, Being, would disclose its essence. Consequently, he combed the writings of Heraclitus, Parmenides, and Anaximander, pre-Socratic thinkers in whose work he thought a primordial relationship to Being, now obscured, was incisively explored. For him, these peerless thinkers represent the epitome of philosophy. Even in Plato and Aristotle, Heidegger contends, the essence of Being is veiled and disappears.115 This line of thinking is suggestive in view of Newman’s statement, cited above, that non-Western art’s abstract quality tells us more of man’s nature than a naturalistic representation of man’s physical contours. Convinced that Western art abandoned the “abstract quality” of non-Western and geometric Greek art in favor of “naturalistic representation,” Newman decried illusionism for obfuscating the more profound realities of “man’s nature.” Curiously, Newman’s distrust of classical Greek art’s overt emphasis on beauty and idealization (which he deemed too sensual to convey the reality of the human condition116) did not extend to Greek drama, which he held in the highest esteem. Sharing Heidegger’s admiration for Greek culture, he titled some of his works: Ulysses, Achilles, Prometheus, and Dionysus, perhaps finding in Homer, Sophocles, and Aeschylus what Heidegger found in Heraclitus, Parmenides, and Anaximander.

But where, exactly, did Newman’s musings on the reality of man’s nature, and Heidegger’s on the truth of Being, lead? For Heidegger, the question of Being first hinged on clarifying the distinction between Being and beings. The word “being,” when used in the plural form (e.g., individual “beings”), refers to all worldly manifestations: animals, plants, minerals, and so forth. “Being” in the broader sense of signifying existence, and used primarily in the singular form, is not a being and yet it is what all individual “beings” have: although all beings are endowed with Being, Being is not a being in the physical sense (like an animal, vegetable, or mineral). Thus, when Heidegger insists that Being is not a being, he means that Being (existence) is not a physical entity, a forgotten distinction that, if understood primordially, reveals something about the essence of existence. Being thus cannot be apprehended directly. If it could, it would be a being, not Being. A chair “has” height, width, color, texture, and any number of other characteristics, and insofar as we recognize a chair as something that is, it “has” existence; it has Being. But even though it is ridiculously self-evident that, insofar as a being exists, it “has” existence, there is no physical aspect of a chair wherein that same existence can be found. “Nowhere among things,” Heidegger writes, “do we find Being.”117 As a result, “we cannot immediately grasp the being of the essent itself, either through the essent—or anywhere else.”118

By having no materiality, Being presents insurmountable obstacles for any would-be investigator. Not surprisingly, Western thought grew insensitive to the dichotomy between Being and beings, a decline, according to Heidegger, that “imparts to Greek thinking the character of a beginning, in that the lighting of the Being of beings, as a lighting is concealed.”119 To rescue Being from its oblivion, to make the primordial aspect of Being manifest—that is, to understand its essence as it was conceived in its original wording—Heidegger will find it in a concept which also held great fascination for Newman: the idea of presence.

Notes

1. Thomas B. Hess, Barnett Newman (New York: Walker, 1969), 54.

2. SWI, 132–33.

3. Martin Heidegger, Zollikon Seminars: Protocols—Conversations—Letters, trans. Franz Mayr and Richard Askay (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1987), 133. In OWL, 121, Heidegger also made another observation along the same lines; “The ‘sign’ in design (Latin signum) is related to secare, to cut—as in saw, sector, segment. To design is to cut a trace. Most of us know the word ‘sign’ only in its debased meaning—lines on a surface. But we make a design also when we cut a furrow into the soil to open it to seed and grow.”

4. Martin Heidegger, “What Is Metaphysics?,” in Brock, Martin Heidegger: Existence and Being, 344. See also IM, 17: “In Greek, ‘beyond something’ is expressed by the word meta. Philosophical inquiry into the realm of being as such is meta ta physika; this inquiry goes beyond the essent, it is metaphysics.”

5. “Introduction,” The Question Concerning Technology, xxii.

6. Theodor Adorno, The Jargon of Authenticity, trans. Knut Tarnowski and Frederic Will (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), 50–51.

7. Martin Heidegger, “Building Dwelling Thinking,” in David Farrell Krell, ed. and trans. Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings, 324.

8. What Is Called Thinking?, 127.

9. IM, 13. See also “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 23: “translation of Greek names into Latin is in no way the innocent process it is considered to this day. Beneath the seemingly literal and thus faithful translation there is concealed, rather, a translation of Greek experience into a different way of thinking. Roman thought takes over the Greek words without a corresponding, equally authentic experience of what they say, without the Greek word. The rootlessness of Western thought begins with this translation.”

10. SWI, 181.

11. Gottfried Boehm, “A New Beginning: Abstraction and the Myth of the ‘Zero Hour,’” in Joan Marter (ed.), Abstract Expressionism: The International Context (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 105.

12. In “Barnett Newman’s Onement I: ‘The Way Up and Down is One and the Same,” Source: Notes in the History of Art 24, no. 1 (2004): 48, Evan Firestone sees concordances between Judaic ideas and those of Heraclitus, of whom both Newman and Heidegger were fond.

13. SWI, 169.

14. IM, 124.

15. IM, 130–31.

16. IM, 134.

17. IM, 138.

18. Martin Heidegger, Parmenides, trans. André Schuwer and Richard Rojcewicz (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1998), 75. (Hereafter referred to as P.)

19. IM, 122.

20. Steiner, Martin Heidegger, 23.

21. Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in David Farrell Krell (ed. and trans.), Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings, 149.

22. Martin Heidegger, “Science and Reflection,” in The Question Concerning Technology, 159.

23. Martin Heidegger, What Is Called Thinking?, 79.

24. SWI, 287.

25. SWI, 64.

26. See “Translators’ Foreword,” in Martin Heidegger, Mindfulness, trans. Parvis Emad and Thomas Kalary (London: Continuum, 2006), xxix.

27. P, 77.

28. SWI, 191–92.

29. SWI, 248.

30. For Newman, there was a very literal connotation to the idea of wiping the slate clean, as he destroyed all of his work prior to 1944. See Jeremy Strick, The Sublime Is Now: The Early Work of Barnett Newman (New York: PaceWildenstein, 1994).

31. SWI, 89.

32. SWI, 67.

33. SWI, 140.

34. IM, 39.

35. IM, 191; the translation quoted here, though, is from Keith Hoeller, “Role of the Early Greeks in Heidegger’s Turning,” Philosophy Today 28 (Spring 1984): 46.

36. SWI, 140.

37. See Thomas Hess, Barnett Newman (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971), and Matthew Baigell, “Barnett Newman’s Stripe Paintings and Kabbalah: A Jewish Take,” American Art 8 (Spring 1994): 34.

38. Barnett Newman, interview with Voice of America in São Paulo, 1965; also quoted in Temkin, Barnett Newman, 192.

39. Barnett Newman, interview with Voice of America in São Paulo, 1965; also quoted in Temkin, Barnett Newman, 192.

40. Harold Rosenberg, Barnett Newman (New York: Abrams, 1978), 78.

41. Yve-Alain Bois, “Newman’s Laterality,” in Reconsidering Barnett Newman, 33.

42. David Sylvester, “Newman—I,” About Modern Art: Critical Essays, 1948–1997 (New York: Henry Holt, 1997), 326.

43. “Barnett Newman’s Stripe Paintings and Kabbalah: A Jewish Take,” 35.

44. See William J. Richardson’s discussion in Heidegger: Through Phenomenology to Thought (New York: Fordham University Press, 2003), 44ff.

45. In “Barnett Newman and the Sublime,” Arts Magazine 62 (February 1988): 38, Michael Zakian writes, “Self-conscious experience is immanently transcendental because our direct participation with the objects around us reveals our superiority to them.”

46. SWI, 64.

47. “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in Poetry, Language, Thought, 36.

48. SWI, 158.

49. Charles Harrison, “Abstract Art: Reading Barnett Newman’s Eve,” in Jason Geiger (ed.), Frameworks for Modern Art (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2003), 127.

50. SWI, 159.

51. See Nancy Aiken, The Biological Origins of Art (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998), 169.

52. In all fairness to Neanderthals, it should be said that, in certain rare instances, flute-like objects and ornaments have been found in their burial sites. But this may not necessarily be significant. The function of the items is still in dispute, and the presence of ornaments has been attributed to Neanderthals borrowing from Homo Sapien practices while both lived contemporaneously.

53. What Is Called Thinking?, 16.

54. See also Barbara Reise, “The Stance of Barnett Newman,” Studio International 179 (February 1970): 51; and Michael Zakian, “Barnett Newman: Painting and a Sense of Place,” Arts Magazine 62 (March 1988): 40.

55. IM, 155.

56. Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. Joan Stambaugh (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 19. (Hereafter referred to as BT.)

57. Gelven, A Commentary, 9.

58. Heidegger, Schelling’s Treatise on the Essence of Human Freedom, 10.

59. SWI, 67.

60. P, 125.

61. P, 149.

62. P, 125.

63. Marin Heidegger, “Remembrance of the Poet,” in Brock, Martin Heidegger: Existence and Being, 258.

64. Martin Heidegger, “Letter on Humanism,” in David Farrell Krell (ed. and trans.), Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings, 218.

65. SWI, 258.

66. FCM, 7.

67. FCM, 13.

68. FCM, 22.

69. What Is Called Thinking?, 132.

70. Martin Heidegger, “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry,” in Brock, Martin Heidegger: Existence and Being, 274.

71. SWI, 8.

72. Martin Heidegger, “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry,” in Brock, Martin Heidegger: Existence and Being, 274.

74. Steiner, Martin Heidegger, 145.

75. “Poetically Man Dwells,” in Poetry, Language, Thought, 218.

76. SWI, 159; see also Mel Bochner, “Barnett Newman: Writing Painting/Painting Writing,” in Reconsidering Barnett Newman, 25.

77. EHP, 127–28.

78. IM, 144.

79. Thomas B. Hess, Barnett Newman (1971), 56.

80. SWI, 48–49.

81. EHP, 156.

82. Martin Heidegger, “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry,” in Brock, Martin Heidegger: Existence and Being, 274. See also Walter H. Cerf, “An Approach to Heidegger’s Ontology,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 1 (December 1940): 184: “It is contained in the definition of man as that being who understands himself as being. Man has this outstanding role among all other beings that, as Heidegger says, he is in order to be.”

83. SWI, 258.

84. IM, 50.

85. What Is Called Thinking?, 101.

86. Mindfulness, 5: In knowing-awareness, the philosopher writes, “we are those who are.”

87. BT, 14.

88. SWI, 258.

89. Mindfulness, 118, 119.

90. Barnett Newman, “Teachers’ Exams—What Is Wrong?,” The Answer, January 1936, 23.

91. What Is Called Thinking?, 6.

92. What Is Called Thinking?, 126.

93. IM, 29.

94. What Is Called Thinking?, 31. “[W]e can grow thought-poor or even thought-less only because man at the core of his being has the capacity to think; has ‘spirit and reason’ and is destined to think.” Discourse on Thinking, trans. John M. Anderson and E. Hans Freund (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), 45.

95. IM, 139–40. “Only as a questioning, historical being,” he concludes, “does man come to himself; only as such is he a self” (IM, 143).

96. Gelven, A Commentary, 23.

97. “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 71.

98. BT, 26.

99. OWL, 112. FCM, 26: “Man, insofar as he exists as man, has always already spoken out about . . . the prevailing whole to which he himself belongs.”

100. See also Mel Bochner, “Barnett Newman: Writing Painting/Painting Writing,” in Reconsidering Barnett Newman, 26.

101. T. B. Hess, Barnett Newman (1969), 55.

102. P, 76.

103. William Richardson, Heidegger: Through Phenomenology to Thought, 554.

104. Martin Heidegger, Gesamtausgabe (Frankfurt: Vittorio Klostermann), Vol. 40, 180–81, cited in Michael Zimmerman, “Ontological Aestheticism: Heidegger, Jünger, and National Socialism,” in The Heidegger Case, 79.

105. IM, 82.

106. OWL, 141.

107. IM, 5.

108. IM, 29.

109. IM, 13.

110. See Christine Kenneally, The First Word: The Search for the Origins of Language (New York: Viking, 2007), 108ff, and Pinker, The Stuff of Thought, 128.

111. IM, 14.

112. Martin Heidegger, “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry,” in Brock, Martin Heidegger: Existence and Being, 275.

113. Intriguingly, Ludwig Wittgenstein expressed a similar opinion, although from another perspective.

114. Martin Heidegger, “Building Dwelling Thinking,” in David Farrell Krell (ed. and trans.), Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings, 326.

115. Martin Heidegger, Early Greek Thinking, trans. David Farell Krell and Frank A. Capuzzi (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 18. (Hereafter EGT.)

116. As David J. Glaser put it, “For Newman decorative art does not so much seduce thought toward a dissipation of its critical element as simply fail to provide food for thought.” “Transcendence in the Vision of Barnett Newman,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 40 (Summer 1980): 417. See also Michael Zakian, “Barnett Newman and the Sublime,” Arts Magazine 62 (February 1988): 35.

117. Martin Heidegger, On Time and Being, trans. Joan Stambaugh (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), 2.

118. IM, 33.

119. EGT, 87.